Does Speed-Normalized Double-Support Reflect Gait Stability in Parkinson’s Disease? A Model-Based Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Dataset Description

2.4. Clinical Assessments

2.5. Gait Data Acquisition

2.6. Data Processing

2.7. Ethical Considerations

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

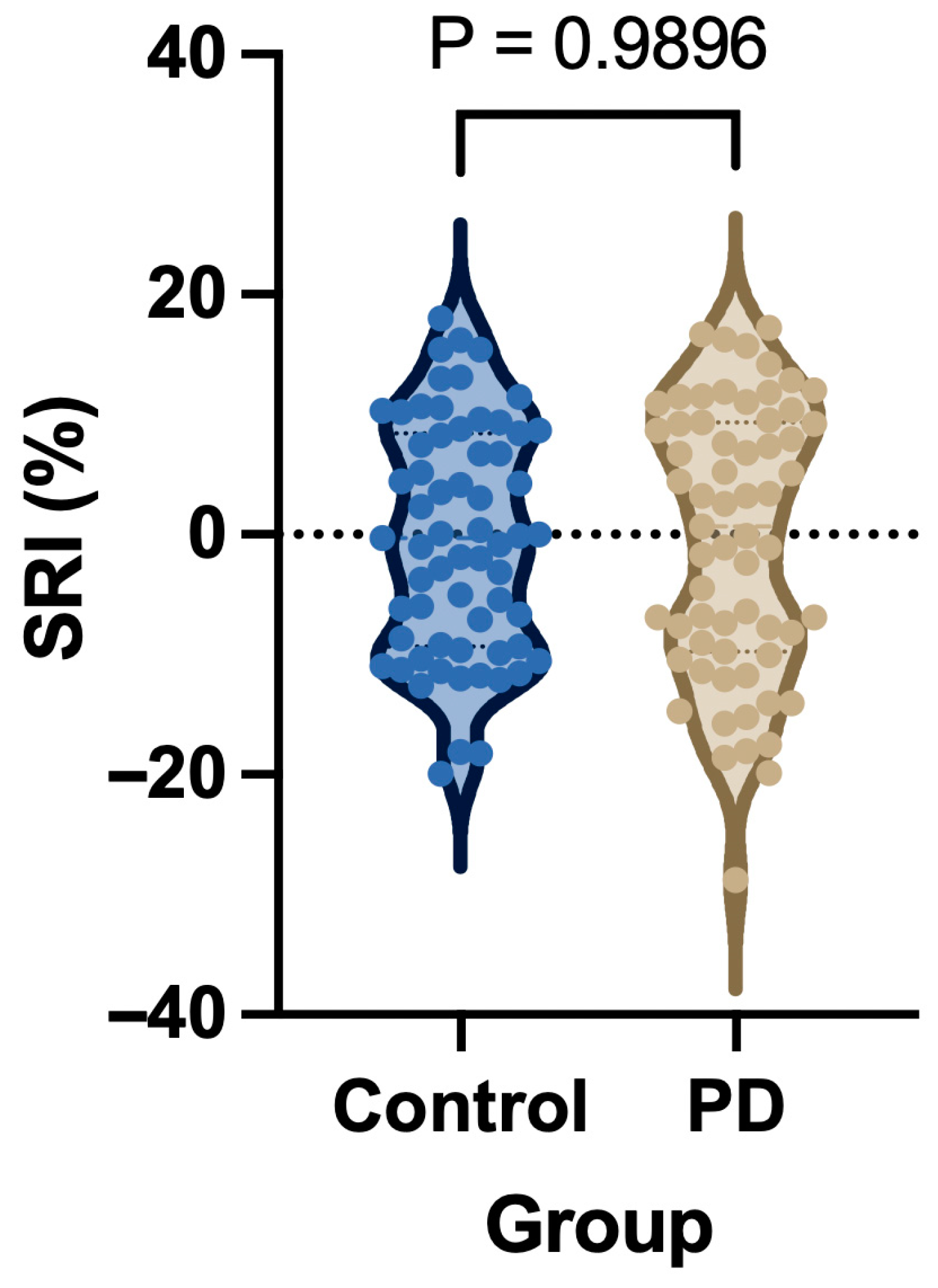

3.2. Spatiotemporal Gait Parameters and Speed-Normalized Stability Indices

3.3. ANCOVA Model Performance

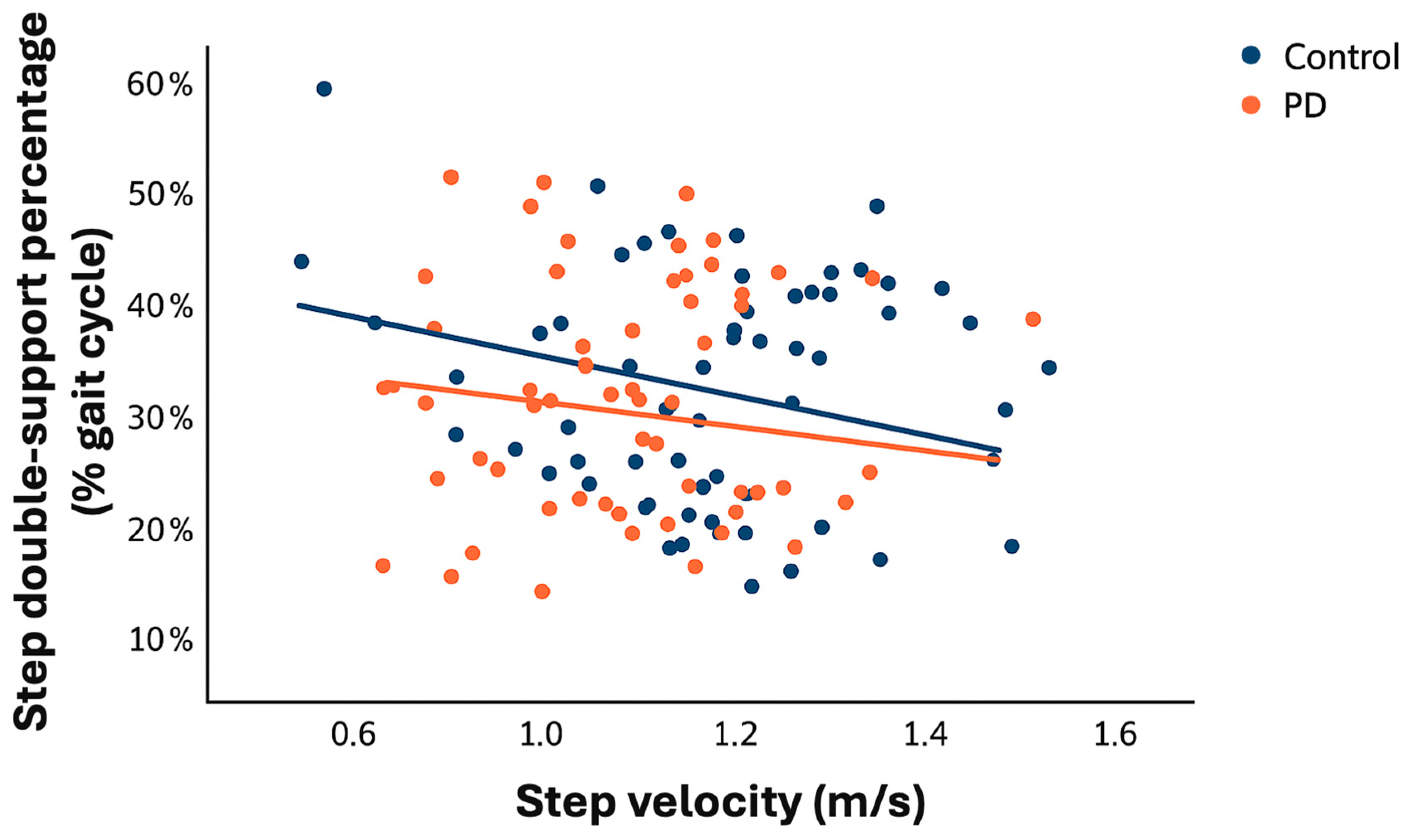

3.4. Relationship Between Walking Velocity and Double-Support

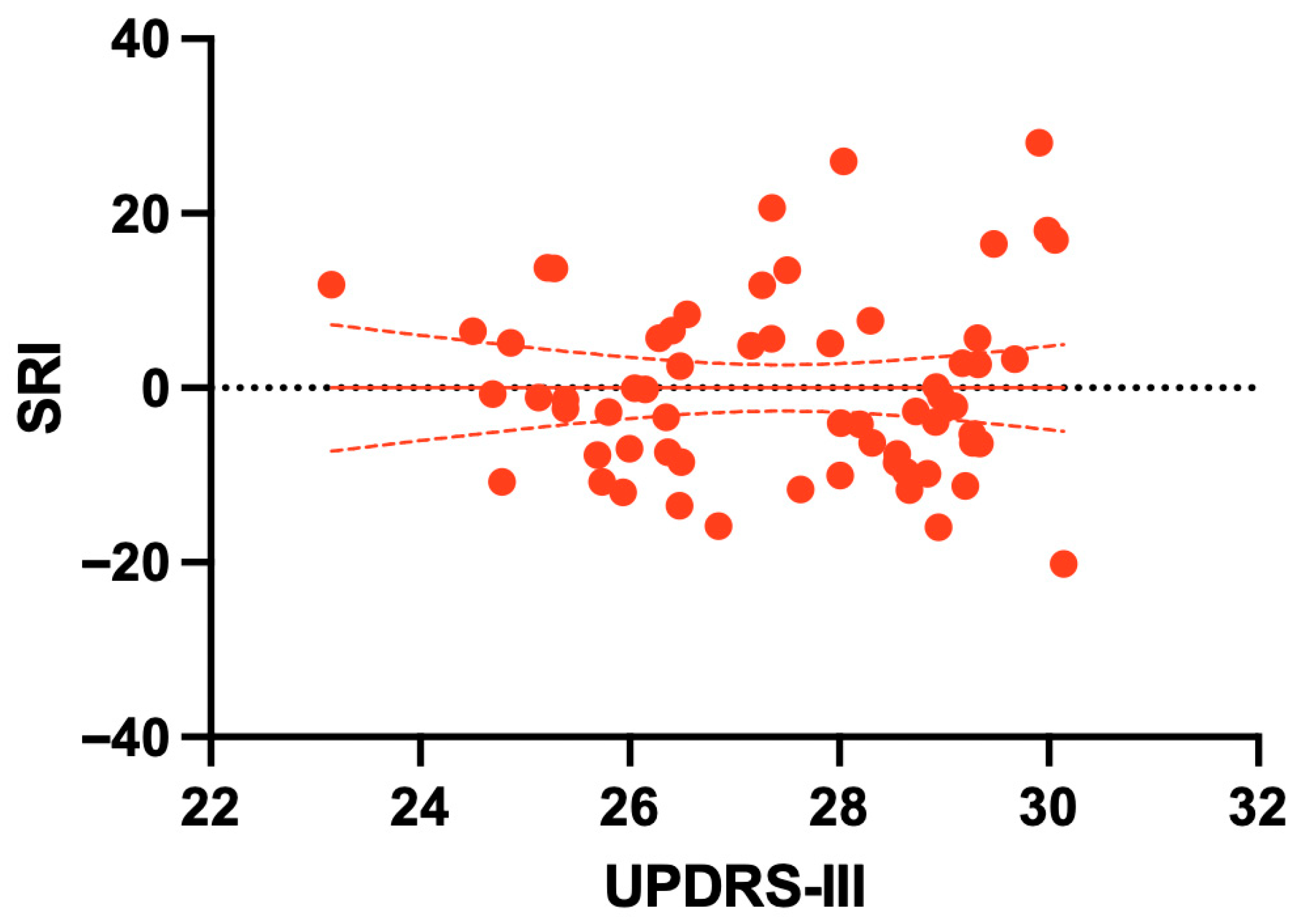

3.5. Clinical Correlates of the Stability Reserve Index

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, M.M.; Brown, G.L.; Woodward, J.L.; Bruijn, S.M.; Gordon, K.E. A novel Movement Amplification environment reveals effects of controlling lateral centre of mass motion on gait stability and metabolic cost. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 190889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- William, P.; Joo, H.K. Balance stability characteristics of human walking with preferred, fast, and slow speeds. In Proceedings of the 7th International Digital Human Modeling Symposium, University of Iowa, Iowa, IA, USA, 23 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tramontano, M.; Orejel Bustos, A.S.; Montemurro, R.; Vasta, S.; Marangon, G.; Belluscio, V.; Morone, G.; Modugno, N.; Buzzi, M.G.; Formisano, R.; et al. Dynamic Stability, Symmetry, and Smoothness of Gait in People with Neurological Health Conditions. Sensors 2024, 24, 2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwerder, M.; Camenzind, U.; Wild, S.; Kim, Y.K.; Taylor, W.R.; Singh, N.B. Probing gait adaptations: The impact of aging on dynamic stability and reflex control mechanisms under varied weight-bearing conditions. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Emmerik, R.E.A.; Hamill, J.; McDermott, W.J. Variability and Coordinative Function in Human Gait. Quest 2005, 57, 102–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caronni, A.; Gervasoni, E.; Ferrarin, M.; Anastasi, D.; Brichetto, G.; Confalonieri, P.; Giovanni, R.D.; Prosperini, L.; Tacchino, A.; Solaro, C.; et al. Local Dynamic Stability of Gait in People with Early Multiple Sclerosis and No-to-Mild Neurological Impairment. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2020, 28, 1389–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schniepp, R.; Wuehr, M.; Neuhaeusser, M.; Kamenova, M.; Dimitriadis, K.; Klopstock, T.; Strupp, M.; Brandt, T.; Jahn, K. Locomotion speed determines gait variability in cerebellar ataxia and vestibular failure. Mov. Disord. 2012, 27, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siragy, T.; Nantel, J. Quantifying Dynamic Balance in Young, Elderly and Parkinson’s Individuals: A Systematic Review. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warabi, T.; Furuyama, H.; Kato, M. Gait bradykinesia: Difficulty in switching posture/gait measured by the anatomical y-axis vector of the sole in Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Brain Res. 2020, 238, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, A.M.; Bauer, D.; Hendrix, C.; Yu, Y.; Nebeck, S.D.; Fergus, S.; Krieg, J.; Wilmerding, L.K.; Blumenfeld, M.; Lecy, E.; et al. Spatiotemporal scaling changes in gait in a progressive model of Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 1041934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanardi, A.P.J.; da Silva, E.S.; Costa, R.R.; Passos-Monteiro, E.; dos Santos, I.O.; Kruel, L.F.M.; Peyré-Tartaruga, L.A. Gait parameters of Parkinson’s disease compared with healthy controls: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.; Amboni, M.; Pisani, N.; Volzone, A.; Calderone, D.; Barone, P.; Amato, F.; Ricciardi, C.; Romano, M. Biomechanics Parameters of Gait Analysis to Characterize Parkinson’s Disease: A Scoping Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuchi, C.A.; Fukuchi, R.K.; Duarte, M. Effects of walking speed on gait biomechanics in healthy participants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Youm, C.; Noh, B.; Park, H.; Cheon, S.-M. Gait Characteristics under Imposed Challenge Speed Conditions in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease During Overground Walking. Sensors 2020, 20, 2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giardini, M.; Turcato, A.M.; Arcolin, I.; Corna, S.; Godi, M. Vertical Ground Reaction Forces in Parkinson’s Disease: A Speed-Matched Comparative Analysis with Healthy Subjects. Sensors 2024, 24, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Mukaino, M.; Ohtsuka, K.; Otaka, Y.; Tanikawa, H.; Matsuda, F.; Tsuchiyama, K.; Yamada, J.; Saitoh, E. Gait characteristics of post-stroke hemiparetic patients with different walking speeds. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2020, 43, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penedo, T.; Kalva-Filho, C.A.; Cursiol, J.A.; Faria, M.H.; Coelho, D.B.; Barbieri, F.A. Spatial-temporal parameters during unobstructed walking in people with Parkinson’s disease and healthy older people: A public data set. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 16, 1354738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo-Silva, F.; Santinelli, F.B.; Felipe, I.I.L.; Silveira, A.P.B.; Vieira, L.H.P.; Alcock, L.; Barbieri, F.A. Temporal dynamics of cortical activity and postural control in response to the first levodopa dose of the day in people with Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res. 2022, 1775, 147727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brucki, S.M.; Nitrini, R.; Caramelli, P.; Bertolucci, P.H.; Okamoto, I.H. Suggestions for utilization of the mini-mental state examination in Brazil. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2003, 61, 777–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, C.G.; Thelen, J.A.; MacLeod, C.M.; Carvey, P.M.; Bartley, E.A.; Stebbins, G.T. Blood levodopa levels and unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale function: With and without exercise. Neurology 1993, 43, 1040–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoehn, M.M.; Yahr, M.D. Parkinsonism: Onset, progression, and mortality. Neurology 1967, 17, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dieën, J.H.; Bruijn, S.M.; Afschrift, M. Assessment of stabilizing feedback control of walking: A tutorial. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2024, 78, 102915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, A.G.B.; Vaz, M.A.P.; Pinho, L.; Félix, J.; Moreira, J.; Pinho, F.; Mesquita, I.A.; Mesquita Montes, A.; Crasto, C.; Sousa, A.S.P. Interlimb Coordination during Double Support Phase of Gait in People with and without Stroke. J. Mot. Behav. 2024, 56, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Cruz, C.; Rojas Ruiz, F.J.; De La Cruz Marquez, J.C.; Gutiérrez-Davila, M. Dual-Task Cost of Discrimination Tasks During Gait in People with Multiple Sclerosis. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 99, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinhardt, L.; Schwesig, R.; Schulze, S.; Donath, L.; Kurz, E. Accuracy of unilateral and bilateral gait assessment using a mobile gait analysis system at different walking speeds. Gait Posture 2024, 109, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.E.; Iansek, R.; Matyas, T.A.; Summers, J.J. Stride length regulation in Parkinson’s disease: Normalization strategies and underlying mechanisms. Brain 1996, 119, 551–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carswell, H.; Schinkel-Ivy, A. Relationships between spatiotemporal and kinematic domains during treadmill gait change across adulthood. Gait Posture 2025, 117, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, G.; Hoppe, M.; Browner, N.; Lewek, M.D. Individuals with Parkinson’s Disease Retain Spatiotemporal Gait Control with Music and Metronome Cues. Mot. Control 2020, 25, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.R.; Simpson, C.S.; van Asseldonk, E.H.F.; van der Kooij, H.; Ijspeert, A.J. Mechanics of very slow human walking. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitek, O.; Kalichová, M.; Hedbávný, P.; Boušek, T.; Baláž, M. Kinematic Relations during Double Support Phase in Parkinsonian Gait. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderink, G.; Harro, C.; Hickox, L.; Zeitler, D.W.; Kilvington, D.; Prevost, R.; Pryson, P. Dynamic Balance in the Gait Cycle Prior to a 90° Turn in Individuals with Parkinson’s Disease. In Human Gait—Recent Findings and Research; Domínguez-Morales, M., Luna-Perejón, F., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J.; Atalaia, T.; Abrantes, J.; Aleixo, P. Gait Biomechanical Parameters Related to Falls in the Elderly: A Systematic Review. Biomechanics 2024, 4, 165–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.H.; Patel, S.; Gavine, B.; Buchanan, T.; Bogdanovic, M.; Sarangmat, N.; Green, A.L.; Bloem, B.R.; FitzGerald, J.J.; Antoniades, C.A. Deep Brain Stimulation and Levodopa Affect Gait Variability in Parkinson Disease Differently. Neuromodulation 2023, 26, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.; Teixeira, L.; Coelho, D. Effect of antiparkinsonian medication on spatiotemporal gait parameters of individuals with Parkinson’s disease: Comparison between individuals with and without freezing of gait. Braz. J. Mot. Behav. 2023, 17, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, B.; Choudhury, S.; Banerjee, R.; Chatterjee, K.; Ghosal, S.; Anand, S.S.; Kumar, H. Analysis of gait in Parkinson’s disease reflecting the effect of l-DOPA. Ann. Mov. Disord. 2019, 2, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharonson, V.; Seedat, N.; Israeli-Korn, S.; Hassin-Baer, S.; Postema, M.; Yahalom, G. Automated Stage Discrimination of Parkinson’s Disease. BIO Integr. 2020, 1, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skidmore, F.M.; Monroe, W.S.; Hurt, C.P.; Nicholas, A.P.; Gerstenecker, A.; Anthony, T.; Jololian, L.; Cutter, G.; Bashir, A.; Denny, T.; et al. The emerging postural instability phenotype in idiopathic Parkinson disease. npj Park. Dis. 2022, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ihlen, E.A.F.; van Schooten, K.S.; Bruijn, S.M.; Pijnappels, M.; van Dieën, J.H. Fractional Stability of Trunk Acceleration Dynamics of Daily-Life Walking: Toward a Unified Concept of Gait Stability. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chini, G.; Ranavolo, A.; Draicchio, F.; Casali, C.; Conte, C.; Martino, G.; Leonardi, L.; Padua, L.; Coppola, G.; Pierelli, F.; et al. Local Stability of the Trunk in Patients with Degenerative Cerebellar Ataxia During Walking. Cerebellum 2017, 16, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M.; Villagra, F.; Castellote, J.M.; Pastor, M.A. Kinematic and Kinetic Patterns Related to Free-Walking in Parkinson’s Disease. Sensors 2018, 18, 4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welmer, A.-K.; Rizzuto, D.; Qiu, C.; Caracciolo, B.; Laukka, E.J. Walking Speed, Processing Speed, and Dementia: A Population-Based Longitudinal Study. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2014, 69, 1503–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, S.; Stuart, D.; Christensen, K.; Chen, A.; Chen, Y. Analysis of Walking Speeds Involving Individuals with Disabilities in Different Indoor Walking Environments. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2015, 142, 04015010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, F.; Begg, R.; Lythgo, N.; Hass, C.J.; Halgamuge, S.; Ackland, D.C. A Multiple Regression Approach to Normalization of Spatiotemporal Gait Features. J. Appl. Biomech. 2016, 32, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terrier, P. From Stability to Complexity: A Systematic Review Protocol on Long-term Divergence Exponents in Gait Analysis. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Control (n = 63) | PD (n = 63) | Between-Group Difference (Control − PD), 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGE, YEARS | 68.32 ± 6.28 | 68.79 ± 7.51 | −0.48 (−2.92 to 1.96) | 0.700 |

| BODY MASS (KG) | 72.05 ± 13.21 | 69.41 ± 13.75 | 2.64 (−2.11 to 7.40) | 0.273 |

| BODY HEIGHT (M) | 1.598 ± 0.081 | 1.62 ± 0.09 | −0.02 (−0.05 to 0.01) | 0.131 |

| BMI (KG/M2) | 28.20 ± 4.66 | 26.37 ± 4.66 | 1.82 (0.18 to 3.47) | 0.030 * |

| MMSE (SCORE) | 27.95 ± 2.02 | 27.49 ± 2.00 | 0.46 (−0.25 to 1.17) | 0.201 |

| SEX, N (%) | ||||

| FEMALE | 45 (71.4%) | 29 (46.0%) | χ2(1) = 8.38 | 0.004 ** |

| MALE | 18 (28.6%) | 34 (54.0%) |

| Variable | Control (n = 63) | PD (n = 63) | Between-Group Difference (Control − PD), 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step velocity (m/s) | 1.21 ± 0.17 | 1.07 ± 0.18 | 0.14 (0.08 to 0.20) | <0.001 ** |

| Stride velocity (m/s) | 1.21 ± 0.18 | 1.07 ± 0.18 | 0.14 (0.08 to 0.20) | <0.001 ** |

| Step DS% (% gait cycle) | 36.78 ± 9.92 | 37.28 ± 11.30 | −0.49 (−4.24 to 3.26) | 0.795 |

| Stride DS% (% gait cycle) | 35.89 ± 9.95 | 36.61 ± 10.63 | 0.28 (−3.35 to 3.91) | 0.880 |

| Speed-normalized predicted double-support (%) | 36.42 ± 9.73 | 36.89 ± 11.97 | −0.47 (−1.12 to 0.19) | 0.159 |

| Stability Reserve Index (SRI) (%) | −3.36 ± 9.64 | −3.38 ± 11.24 | 0.03 (−3.67 to 3.72) | 0.989 |

| Parameter | β | Std. Error | t | p-Value | 95% CI for β |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 10.553 | 23.401 | 0.451 | 0.653 | −35.78 to 56.89 |

| Group (Control = 1) | −0.126 | 2.107 | −0.060 | 0.952 | −4.30 to 4.05 |

| Centered step velocity | −4.936 | 7.681 | −0.643 | 0.522 | −20.15 to 10.27 |

| Group × Centered step velocity interaction | 9.507 | 10.959 | 0.868 | 0.387 | −12.19 to 31.21 |

| Age (years) | 0.255 | 0.141 | 1.806 | 0.073 | −0.03 to 0.54 |

| Body height (m) | 6.144 | 11.606 | 0.529 | 0.598 | −16.84 to 29.13 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | −0.044 | 0.210 | −0.208 | 0.836 | −0.46 to 0.37 |

| A. Spearman correlations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | ρ | p-Value | |||

| SRI vs. UPDRS-III | 0.129 | 0.313 | |||

| SRI vs. Hoehn & Yahr stage | 0.223 | 0.079 | |||

| UPDRS-III vs. Hoehn & Yahr | 0.545 | <0.001 | |||

| B. Multiple regression predicting SRI | |||||

| Predictor | β | Std. Error | t | p-Value | 95% CI for β |

| Intercept | −17.470 | 36.145 | −0.483 | 0.631 | −89.85 to 54.91 |

| UPDRS-III | 0.061 | 0.160 | 0.380 | 0.705 | −0.26 to 0.38 |

| Hoehn & Yahr stage | 4.607 | 3.725 | 1.237 | 0.221 | −2.85 to 12.07 |

| Age (years) | 0.014 | 0.200 | 0.009 | 0.946 | −0.39 to 0.41 |

| Body height (m) | 3.130 | 16.829 | 0.186 | 0.853 | −30.57 to 36.83 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | −0.013 | 0.336 | −0.040 | 0.968 | −0.69 to 0.66 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sangkarit, N.; Tapanya, W. Does Speed-Normalized Double-Support Reflect Gait Stability in Parkinson’s Disease? A Model-Based Analysis. Biomechanics 2025, 5, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics5040102

Sangkarit N, Tapanya W. Does Speed-Normalized Double-Support Reflect Gait Stability in Parkinson’s Disease? A Model-Based Analysis. Biomechanics. 2025; 5(4):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics5040102

Chicago/Turabian StyleSangkarit, Noppharath, and Weerasak Tapanya. 2025. "Does Speed-Normalized Double-Support Reflect Gait Stability in Parkinson’s Disease? A Model-Based Analysis" Biomechanics 5, no. 4: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics5040102

APA StyleSangkarit, N., & Tapanya, W. (2025). Does Speed-Normalized Double-Support Reflect Gait Stability in Parkinson’s Disease? A Model-Based Analysis. Biomechanics, 5(4), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics5040102