Effects of Progressive Elastic Resistance on Kinetic Chain Exercises Performed on Different Bases of Support in Healthy Adults: A Statistical Parametric Mapping Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

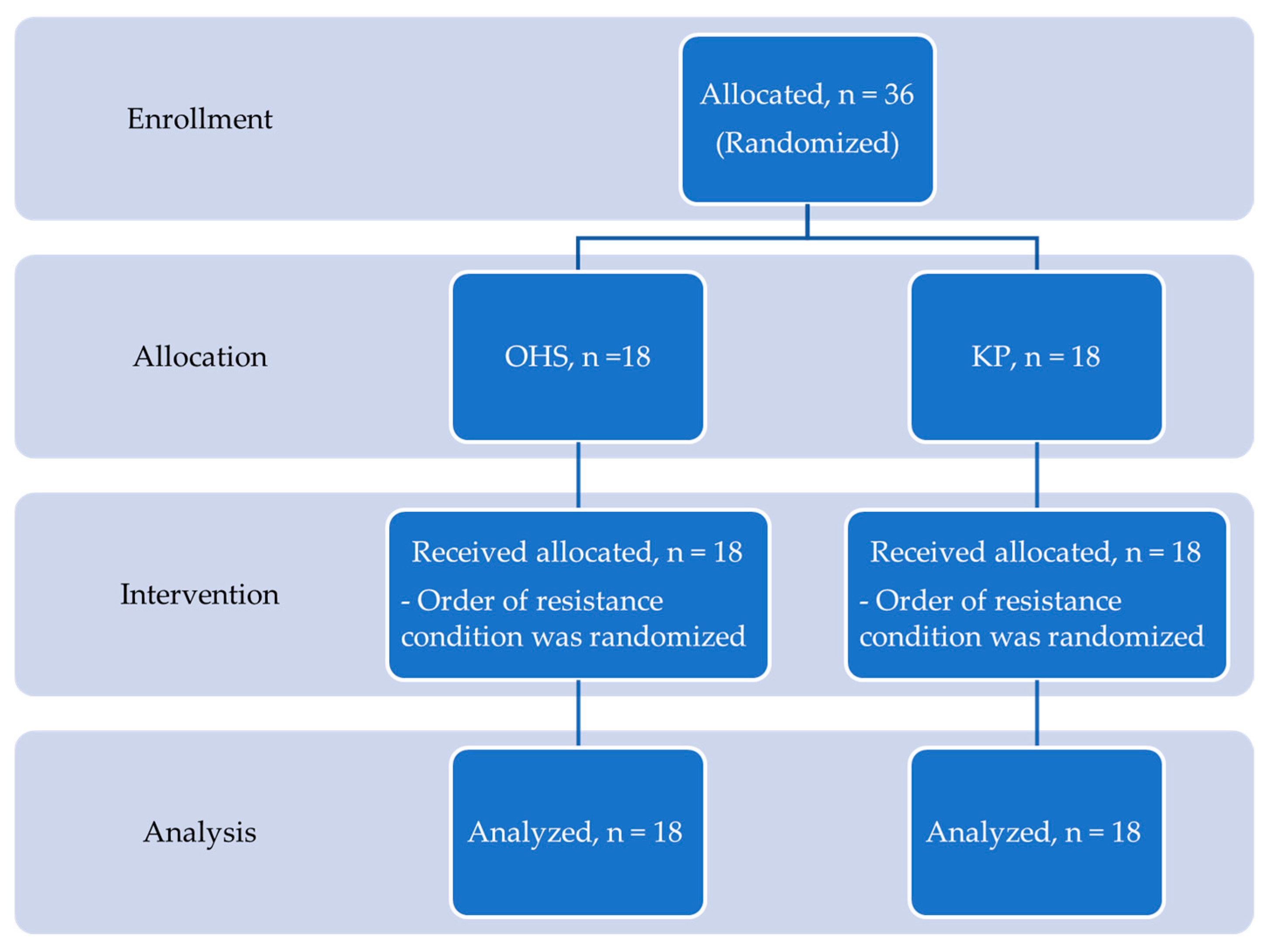

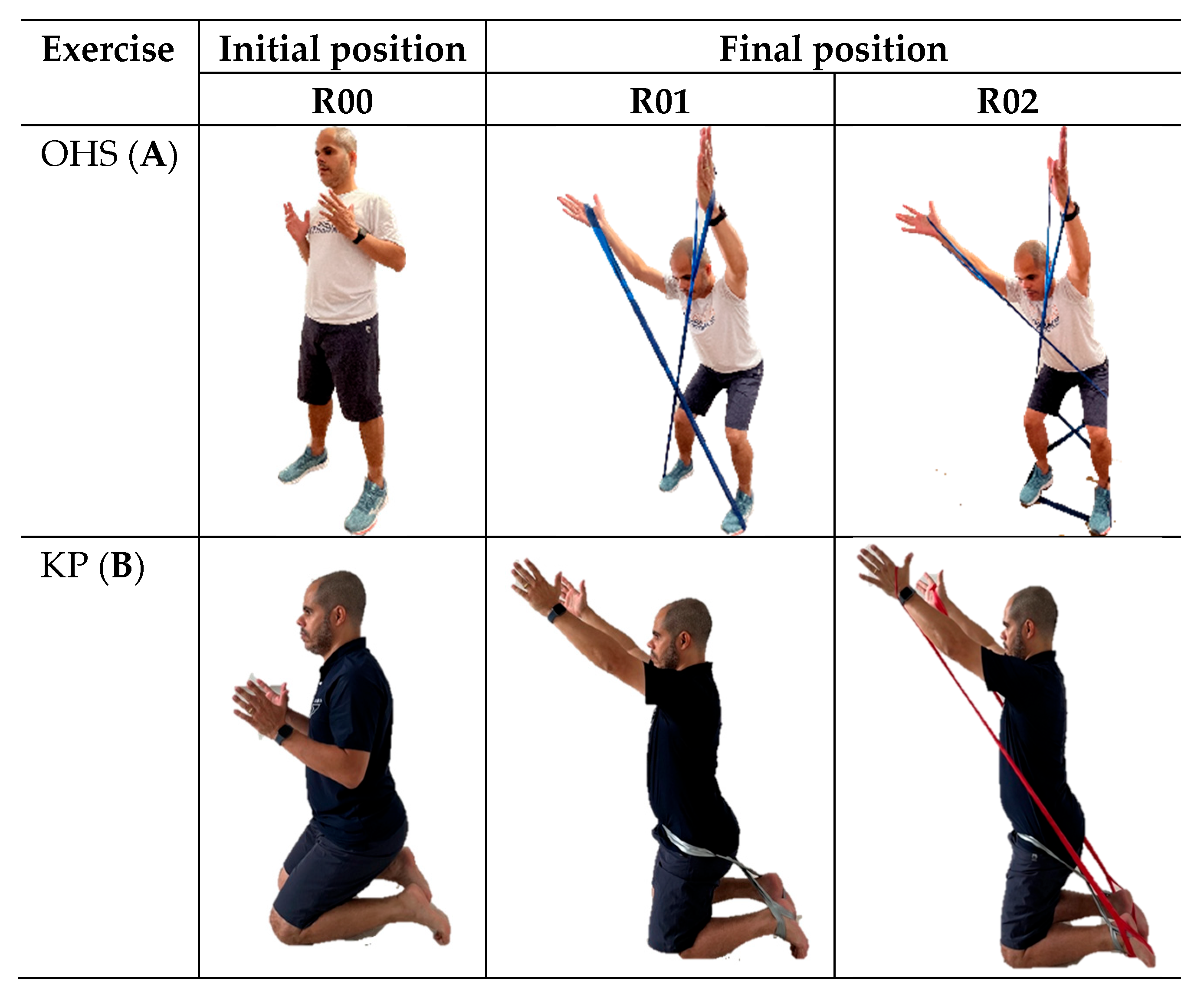

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Sample Size Estimation

2.2. Instrumentation and Procedures

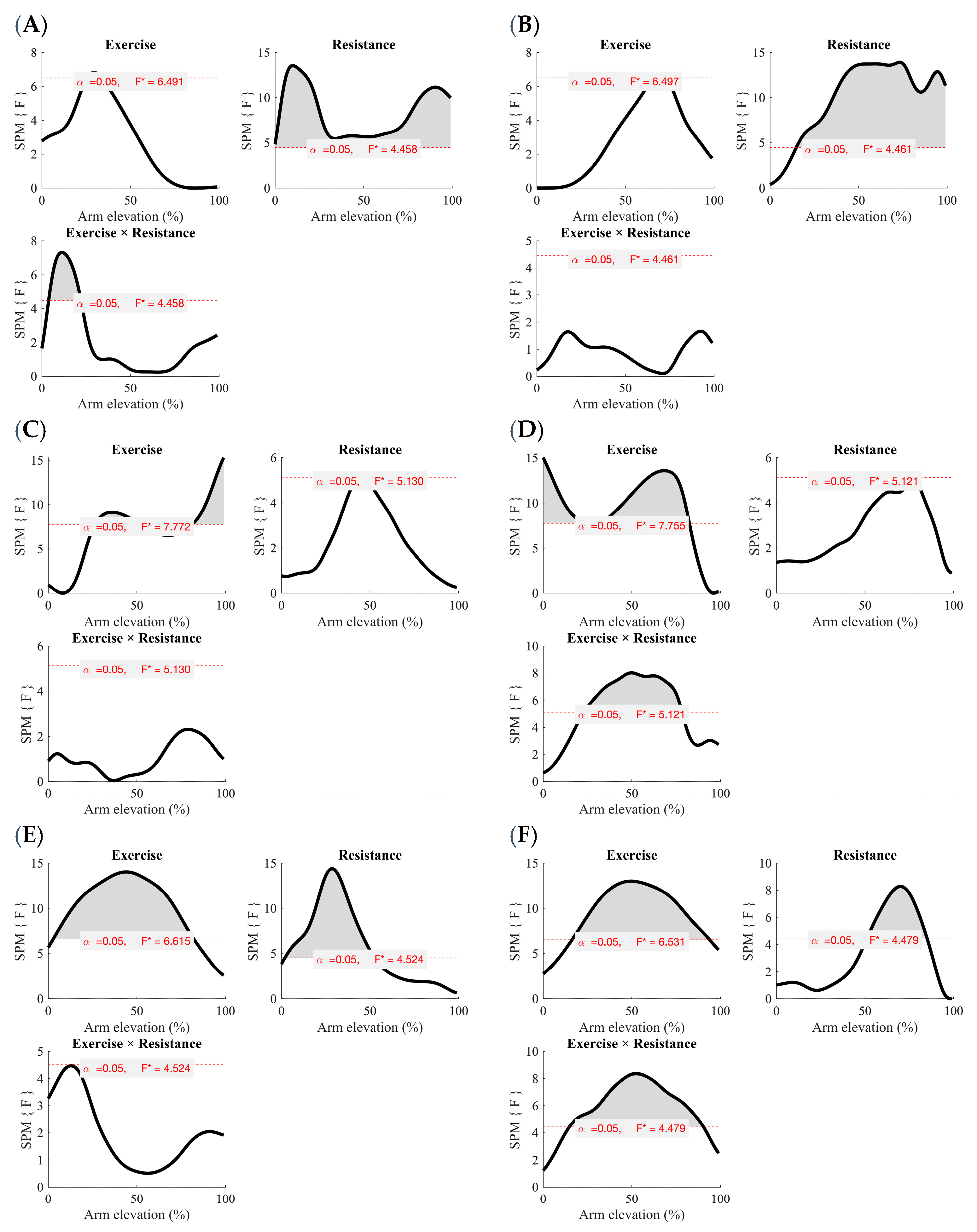

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

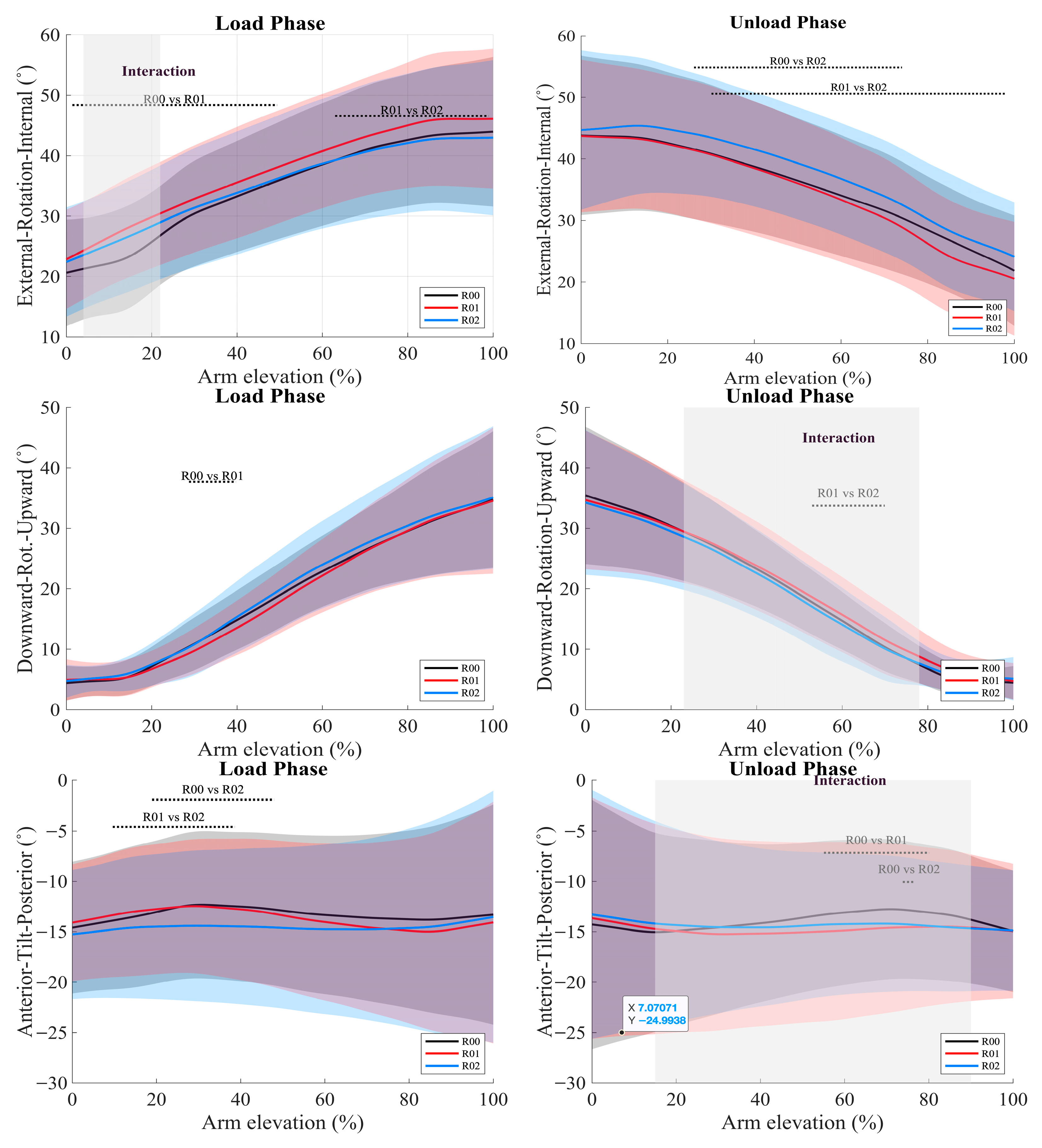

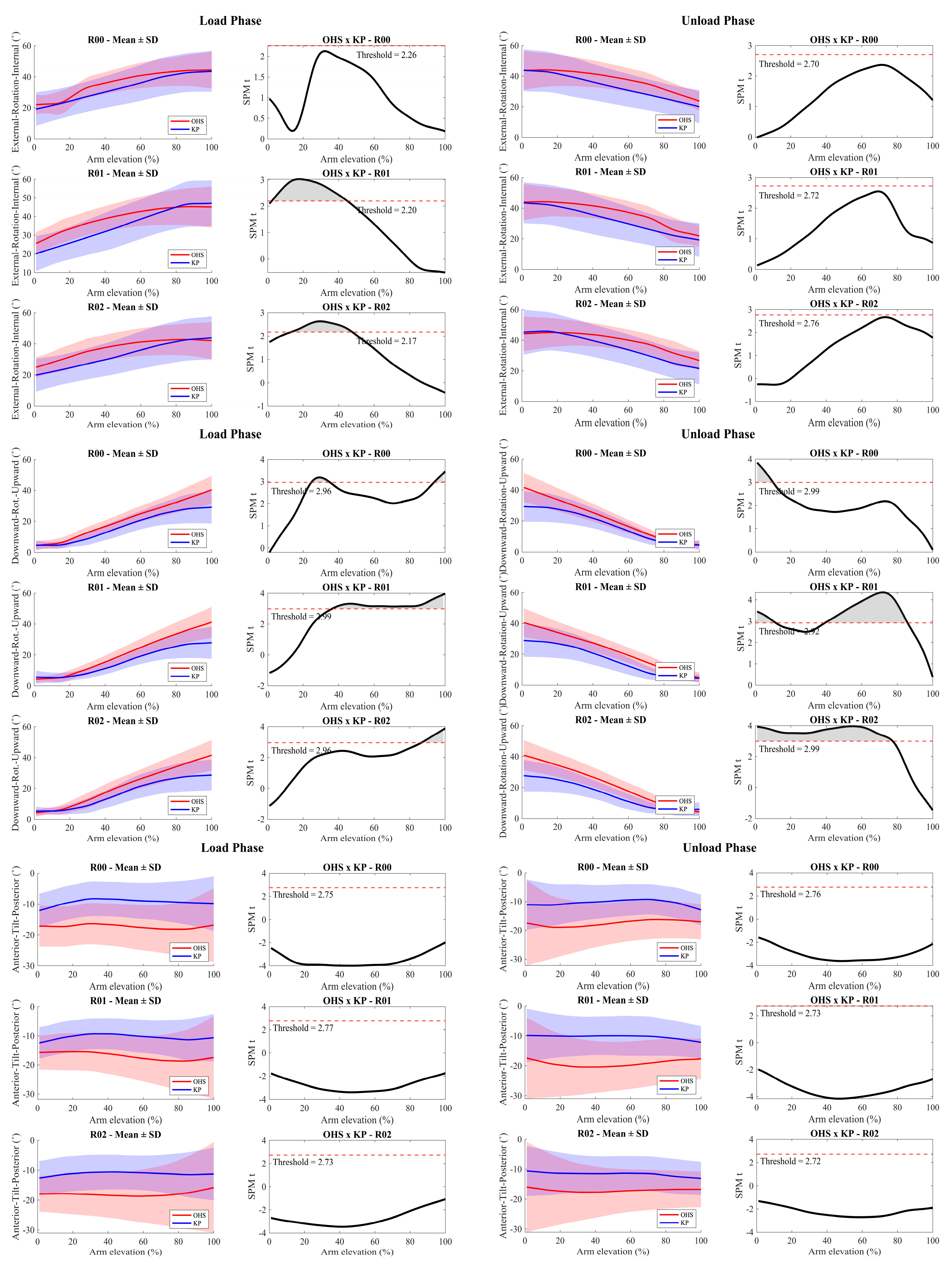

3.1. Scapular Internal/External Rotation

3.2. Scapular Upward/Downward Rotation

3.3. Scapular Posterior/Anterior Tilt

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Exercise Type

4.2. Effect of Resistance

4.3. Clinical Implications and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reijneveld, E.A.; Noten, S.; Michener, L.A.; Cools, A.; Struyf, F. Clinical outcomes of a scapular-focused treatment in patients with subacromial pain syndrome: A systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2017, 51, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castelein, B.; Cagnie, B.; Parlevliet, T.; Cools, A. Superficial and Deep Scapulothoracic Muscle Electromyographic Activity During Elevation Exercises in the Scapular Plane. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2016, 46, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, R.; Bernhardsson, S.; Nordeman, L. Effects of eccentric exercise in patients with subacromial impingement syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, H.; Harrold, M.E.; Cavalheri, V.; McKenna, L. Scapular focused interventions to improve shoulder pain and function in adults with subacromial pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2018, 34, 653–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valles-Carrascosa, E.; Gallego-Izquierdo, T.; Jimenez-Rejano, J.J.; Plaza-Manzano, G.; Pecos-Martin, D.; Hita-Contreras, F.; Achalandabaso Ochoa, A. Pain, motion and function comparison of two exercise protocols for the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers in patients with subacromial syndrome. J. Hand Ther. 2018, 31, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboodarda, S.J.; Page, P.A.; Behm, D.G. Muscle activation comparisons between elastic and isoinertial resistance: A meta-analysis. Clin. Biomech. 2016, 39, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J.S.S.; Machado, A.F.; Micheletti, J.K.; de Almeida, A.C.; Cavina, A.P.; Pastre, C.M. Effects of training with elastic resistance versus conventional resistance on muscular strength: A systematic review and meta-analysis. SAGE Open Med. 2019, 7, 2050312119831116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelein, B.; Cagnie, B.; Cools, A. Scapular muscle dysfunction associated with subacromial pain syndrome. J. Hand Ther. 2017, 30, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cools, A.M.; Maenhout, A.G.; Vanderstukken, F.; Decleve, P.; Johansson, F.R.; Borms, D. The challenge of the sporting shoulder: From injury prevention through sport-specific rehabilitation toward return to play. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2021, 64, 101384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, E.; Lewis, J.S.; Gibson, J.; Morgan, C.; Halaki, M.; Ginn, K.; Yeowell, G. Role of the kinetic chain in shoulder rehabilitation: Does incorporating the trunk and lower limb into shoulder exercise regimes influence shoulder muscle recruitment patterns? Systematic review of electromyography studies. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2020, 6, e000683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciascia, A.; Thigpen, C.; Namdari, S.; Baldwin, K. Kinetic chain abnormalities in the athletic shoulder. Sports Med. Arthrosc. Rev. 2012, 20, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borms, D.; Maenhout, A.; Cools, A.M. Incorporation of the Kinetic Chain Into Shoulder-Elevation Exercises: Does It Affect Scapular Muscle Activity? J. Athl. Train. 2020, 55, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaremski, J.L.; Wasser, J.G.; Vincent, H.K. Mechanisms and Treatments for Shoulder Injuries in Overhead Throwing Athletes. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, G.D.; Washington, J.K.; Barfield, J.W.; Gascon, S.S.; Gilmer, G. Quantitative Analysis of Proximal and Distal Kinetic Chain Musculature During Dynamic Exercises. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 1545–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picha, K.J.; Almaddah, M.R.; Barker, J.; Ciochetty, T.; Black, W.S.; Uhl, T.L. Elastic Resistance Effectiveness on Increasing Strength of Shoulders and Hips. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 931–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguin, R.C.; Cudlip, A.C.; Holmes, M.W.R. The Efficacy of Upper-Extremity Elastic Resistance Training on Shoulder Strength and Performance: A Systematic Review. Sports 2022, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, P.A.; Blasczyk, J.C.; Souza Junior, G.; Lagoa, K.F.; Soares, M.; de Oliveira, R.J.; Filho, P.; Carregaro, R.L.; Martins, W.R. Effects of Elastic Resistance Exercise on Muscle Strength and Functional Performance in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Phys. Act. Health 2017, 14, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borms, D.; Maenhout, A.; Berckmans, K.; Spanhove, V.; Vanderstukken, F.; Cools, A. Scapulothoracic muscle activity during kinetic chain variations of a prone elevation exercise. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2022, 26, 100420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Mey, K.; Danneels, L.; Cagnie, B.; Van den Bosch, L.; Flier, J.; Cools, A.M. Kinetic chain influences on upper and lower trapezius muscle activation during eight variations of a scapular retraction exercise in overhead athletes. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2013, 16, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserberger, K.W.; Downs, J.L.; Barfield, J.W.; Williams, T.K.; Oliver, G.D. Lumbopelvic-Hip Complex and Scapular Stabilizing Muscle Activations During Full-Body Exercises With and Without Resistance Bands. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 2840–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.K.; Jayabalan, P.; Kibler, W.B.; Press, J. The Kinetic Chain Revisited: New Concepts on Throwing Mechanics and Injury. Pm&r 2016, 8, S69–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, H.S.; Kim, J.H.; Lim, Y.J. The Effect of the Base of Support on Anticipatory Postural Adjustment and Postural Stability. J. Korean Phys. Ther. 2017, 29, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hamill, J.; Knutzen, K.; Derrick, T.R. Biomechanical Basis of Human Movement, 4th ed.; Wolters Kluwer Health: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2015; p. xi. 419p. [Google Scholar]

- Salles, F.L.P.; Pascoal, A.G. A Kinematic Study on the Use of Overhead Squat Exercise with Elastic Resistance on the Shoulder Kinetic Chain Approach. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salles, F.L.P.; Pascoal, A.G. Enhancing Shoulder Kinetic Chain Rehabilitation Using Elastic Resistance in Kneeling Positions. A Kinematics Study. JOSPT Open 2025, 3, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, M.C.; Farwell, K.E.; Gaven, S.L.; Weinhandl, J.T. Weight-Bearing Dorsiflexion Range of Motion and Landing Biomechanics in Individuals With Chronic Ankle Instability. J. Athl. Train. 2015, 50, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoch, M.C.; McKeon, P.O. Joint mobilization improves spatiotemporal postural control and range of motion in those with chronic ankle instability. J. Orthop. Res. 2011, 29, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.M.; Cynn, H.S.; Choung, S.D. Musculoskeletal predictors of movement quality for the forward step-down test in asymptomatic women. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2013, 43, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotta, G.H.; Queiroz, P.O.P.; de Lemos, T.W.; Rossi, D.M.; Scatolin, R.O.; de Oliveira, A.S. Immediate effect of scapula-focused exercises performed with kinematic biofeedback on scapular kinematics in individuals with subacromial pain syndrome. Clin. Biomech. 2018, 58, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bench, R.W.; Thompson, S.E.; Cudlip, A.C.; Holmes, M.W. Examining Muscle Activity Differences During Single and Dual Vector Elastic Resistance Exercises. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2021, 16, 322–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; van der Helm, F.C.; Veeger, H.E.; Makhsous, M.; Van Roy, P.; Anglin, C.; Nagels, J.; Karduna, A.R.; McQuade, K.; Wang, X.; et al. ISB recommendation on definitions of joint coordinate systems of various joints for the reporting of human joint motion-Part II: Shoulder, elbow, wrist and hand. J. Biomech. 2005, 38, 981–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustin, R.M.; Medina-Mirapeix, F.; Gacto-Sanchez, M.; Canovas-Ambit, G.; Vecchia, A.A. Mechanical Evaluation of the Resistance of Theraband CLX. J. Sport Rehabil. 2023, 32, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataky, T.C. Generalized n-dimensional biomechanical field analysis using statistical parametric mapping. J. Biomech. 2010, 43, 1976–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ridder, R.; Willems, T.; Vanrenterghem, J.; Robinson, M.; Pataky, T.; Roosen, P. Gait kinematics of subjects with ankle instability using a multisegmented foot model. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2013, 45, 2129–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzian, R.; Plonsky, L. Eta- and partial eta-squared in L2 research: A cautionary review and guide to more appropriate usage. Second Lang. Res. 2018, 34, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibler, W.B.; McMullen, J.; Uhl, T. Shoulder rehabilitation strategies, guidelines, and practice. Orthop. Clin. N. Am. 2001, 32, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravichandran, H.; Janakiraman, B.; Gelaw, A.Y.; Fisseha, B.; Sundaram, S.; Sharma, H.R. Effect of scapular stabilization exercise program in patients with subacromial impingement syndrome: A systematic review. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2020, 16, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, R.L.; Braman, J.P.; Laprade, R.F.; Ludewig, P.M. Comparison of 3-dimensional shoulder complex kinematics in individuals with and without shoulder pain, part 1: Sternoclavicular, acromioclavicular, and scapulothoracic joints. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2014, 44, A636–A638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, D.; Durke, D.; Cotter, J.A.; Escobar, K.A.; Schick, E.E. A Comparison of Muscle Activation Among the Front Squat, Overhead Squat, Back Extension and Plank. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2020, 13, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, R.L.; Braman, J.P.; Ludewig, P.M. The Impact of Decreased Scapulothoracic Upward Rotation on Subacromial Proximities. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2019, 49, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, M.D.; Landin, D.; Page, P.A. Dynamic acromiohumeral interval changes in baseball players during scaption exercises. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011, 20, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.L.; Andersen, C.H.; Mortensen, O.S.; Poulsen, O.M.; Bjornlund, I.B.; Zebis, M.K. Muscle activation and perceived loading during rehabilitation exercises: Comparison of dumbbells and elastic resistance. Phys. Ther. 2010, 90, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraldsson, B.T.; Andersen, C.H.; Erhardsen, K.T.; Zebis, M.K.; Micheletti, J.K.; Pastre, C.M.; Andersen, L.L. Submaximal Elastic Resistance Band Tests to Estimate Upper and Lower Extremity Maximal Muscle Strength. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, A.F.; Souto, L.R.; Silva, J.S.; Andersen, L.L. Determination of shoulder abduction strength using a submaximal elastic band test. J. Perform. Health Res. 2017, 1, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Forte, F.C.; de Castro, M.P.; de Toledo, J.M.; Ribeiro, D.C.; Loss, J.F. Scapular kinematics and scapulohumeral rhythm during resisted shoulder abduction--implications for clinical practice. Phys. Ther. Sport 2009, 10, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascoal, A.G.; Helm, F.C.T.; Correia, P.P.; Carita, I. Effects of different arm external loads on the scapulo-humeral rhythm. Clin. Biomech. 2000, 15, S21–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Overhead Squat (OHS) | Kneeling Position (KP) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | S.E. | Mean (SD) | S.E. | ||

| Age (years) | 21.9 (3.7) | 0.8 | 21.1 (1.6) | 0.4 | 0.413 |

| Mass (kg) | 77.8 (13.9) | 3.2 | 76.7 (12.5) | 2.9 | 0.798 |

| Height (m) | 1.75 (0.1) | 0.0 | 1.78 (0.1) | 0.0 | 0.287 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.1 (4.2) | 0.9 | 24.1 (3.6) | 0.8 | 0.439 |

| Activity (min/week) | 325.8 (213.7) | 49.0 | 296.1 (196.7) | 46.3 | 0.664 |

| Band Color | Tension (kg, 100% Elongation) | OHS (% Body Mass) | KP (% Body Mass) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Red | 1.88 | - | 2 |

| Blue | 2.82 | 4 | - |

| Black | 3.72 | 5 | 5 |

| Gray | 6.21 | - | 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salles, F.L.P.; Pascoal, A.G. Effects of Progressive Elastic Resistance on Kinetic Chain Exercises Performed on Different Bases of Support in Healthy Adults: A Statistical Parametric Mapping Approach. Biomechanics 2025, 5, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics5040103

Salles FLP, Pascoal AG. Effects of Progressive Elastic Resistance on Kinetic Chain Exercises Performed on Different Bases of Support in Healthy Adults: A Statistical Parametric Mapping Approach. Biomechanics. 2025; 5(4):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics5040103

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalles, Fagner Luiz Pacheco, and Augusto Gil Pascoal. 2025. "Effects of Progressive Elastic Resistance on Kinetic Chain Exercises Performed on Different Bases of Support in Healthy Adults: A Statistical Parametric Mapping Approach" Biomechanics 5, no. 4: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics5040103

APA StyleSalles, F. L. P., & Pascoal, A. G. (2025). Effects of Progressive Elastic Resistance on Kinetic Chain Exercises Performed on Different Bases of Support in Healthy Adults: A Statistical Parametric Mapping Approach. Biomechanics, 5(4), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics5040103