Abstract

Neurotrauma continues to contribute to significant mortality and disability. The need for better protective equipment is apparent. This review focuses on improved helmet design and the necessity for continued research. We start by highlighting current innovations in helmet design for sport and subsequent utilization in the lay community for construction. The current standards by sport and organization are summarized. We then address current standards within the military environment. The pathophysiology is discussed with emphasis on how helmets provide protection. As innovative designs emerge, protection against secondary injury becomes apparent. Much research is needed, but this focused paper is intended to serve as a catalyst for improvement in helmet design and implementation to provide more efficient and reliable neuroprotection across broad arenas.

1. Introduction

Neurotrauma is an important, often preventable cause of morbidity and mortality. Between 180 and 250 traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) occur per 100,000 population per year in the U.S. [1]. Helmets have been employed by humans for thousands of years and have served as a crucial instrument by which we protect ourselves from and minimize the effects of traumatic brain injury [2]. Substantial evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses points toward the protective effectiveness (often >60%) of helmets in preventing TBIs in athletes, cyclists and motorcyclists [3,4,5,6]. However, when stratifying TBI by severity, helmets may be less effective or even ineffective in preventing milder forms of TBI such as concussion [2]. Helmet design has been predicated on linear acceleration as a metric corresponding to head injury [7,8]. This has served well in preventing catastrophic injuries. However, rotational acceleration is more likely implicated in the pathophysiology of milder brain injuries, including concussion [7].

Substantial challenges exist in research involving helmets. For example, a diversity of helmet types based on sport and occupation limits statistical power for studies, along with nonuniform definitions of concussion [2]. Furthermore, prospective studies involving helmets are unethical, and animal models of helmets might not be comparable to those involving humans [2]. Material scientist, engineer, neuroscientist, neurologist, and neurosurgeon inputs will be essential to design better helmets.

The following literature review aims to discuss helmet design in various contexts, along with suggested steps to promote better protection against neurotrauma. A Pubmed search was employed with key terms including “neurotrauma”, “TBI”, “concussion”, “helmet”, and stratified by helmet context, including construction, military, and sport.

2. Current Sports Helmet Design

The mandated use of helmets in organized sports dates back as early as the 1940’s when the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) and National Football League (NFL) made helmets a requirement for players to reduce head-related injuries [9]. Since this time, multiple organizations have developed standards for testing and producing sports helmets (Table 1). While the implementation of sports helmets has successfully reduced catastrophic head-related injuries, including traumatic brain injuries (TBI) and orofacial injuries, the risk of concussive injuries remains unmitigated. This discrepancy in selective protection may be explained by how helmets are tested and certified, with the current standard for testing helmets focusing on the use of linear acceleration, which has demonstrated a reduction of TBI and skull fractures, but not concussive injury [10]. Research has demonstrated that the primary mechanism of injury leading to concussions in sports is the result of rotational acceleration, which is not explicitly tested for by certifying organizations [11,12].

Current sports helmets are designed to protect against punches, falls, projectiles, collisions, and abrasion, and can be grossly organized into two main categories—single-impact and multi-impact helmets [13]. However, virtually all current sports helmets have the basic design of an inner comfort liner, an impact energy attenuating liner, a restraint system, and an outer shell [14]. Single-impact helmets are designed to withstand high-impact encounters only once. Examples of these include bicycle, mountaineering, and equestrian helmets. The energy attenuating liner in these helmets is typically constructed of lightweight expanded polystyrene (EPS) foam, which does well in dissipating energy, but permanently deforms after impact [9]. On the other hand, multi-impact helmets are designed to withstand multiple impacts and are used in US football, hockey, motorcross, and rugby. The resilience to multiple impacts is accomplished by construction with either vinyl nitrile (VN) or expanded polypropylene (EPP) foam for the energy attenuating liner. VN and EPP can return to their original form after impact; however, VN performs better with lower energy impacts than EPP, which performs better at higher energy impacts [9,15]. In both helmets, the outer shell functions to distribute the force of impact along the area of the energy attenuating liner. Shells are commonly constructed of polycarbonate (PC) or ABS plastic, but some helmets may have hard shells composed of composites, such as fiberglass or carbon fiber [7,16].

Further variations in helmet design exist according to the dangers encountered in each sport, as well as practicality, ease of use, and aesthetics. Sports (e.g., lacrosse, hockey, and baseball) where the impact from a projectile is of concern may implement a face guard (typically either a wired frame or an extension of the helmet’s shell) to protect against orofacial injuries [17,18]. Cycling and mountaineering helmets are often engineered to be highly aerodynamic and as light as possible to avoid hindering the user’s performance [19]. Helmets used in motorcycle-variant sports are designed with thicker protective layers that aerodynamically encapsulate the entire head to protect against greater risks associated with high speed [20]. A list of sports helmet types, activities, and applicable standards may be found in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 2.

Sport helmets categorized by activity [14,21].

Table 1.

Sports helmet standards (‘x’ indicates standard) [14,21].

Table 1.

Sports helmet standards (‘x’ indicates standard) [14,21].

| Sport Category | ASTM | AS/NZS | CSA | DOT | EN (Incl. BSI, DIN NSAI) | FIFA, FISI, IHF, IRB | NOCSAE | ISO | Snell |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Football | x | x | |||||||

| Animal Riding | x | ||||||||

| Baseball | x | x | |||||||

| Cricket | x | x (BSI) | |||||||

| Cycling Sports | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Football | x | ||||||||

| Ice Hockey | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Lacrosse | x | ||||||||

| Motorized Sports | x | x | |||||||

| Mountaineering | x | x | |||||||

| Pole Vaulting | x | ||||||||

| Polo | x | ||||||||

| Rugby | x (IRB) | ||||||||

| Skateboard Sports | x | x | |||||||

| Snow Sports | x | x | x | ||||||

| Water Sports | x |

AS/NZS, Standards Australia/New Zealand Standards; ASTM, ASTM International; BSI, none; CSA, Canadian Standards Association; DIN, Germany Industry Standards; DOT, Department of Transportation; FIFA, Federation International Football Associations; FIS, International Ski Federation; IIHF, International Ice Hockey Federation; IRB, International Rugby Board; ISO, International Standards Organization; NOCSAE, National Operating Committee on Standards for Athletic Equipment; NSAI, National Standards Authority Ireland; Snell, Snell Memorial Foundation.

3. Current Military Helmet Design

The current issue US military helmet for combat use is the advanced combat helmet (ACH), and previously was the personnel armor system for ground troops (PASGT) in the late 1990’ and early 2000s [24]. Prior work has highlighted the blunt impact standard limitation to linear head acceleration [25], with the need to focus on rotational head motion, the likely mechanism contributing to diffuse axonal injury (DAI) [25,26,27,28]. Military specification (mil-spec) requires a blunt impact acceleration limit testing for pass/fail criteria of the ACH, but does not require rotational component testing [27]. Blast-induced TBI (BTBI) is also a mechanism of combat-induced diffuse axonal injury where blast waves cause rotational forces on the brain to induce DAI.

The ACH is equipped with high-strength Kevlar 129 fibers, housed in a 7.8 mm thick composite shell [2,29]. Previous literature has highlighted the efficacy of the ACH head protection in reduced likelihood of blast-induced mild TBI (mTBI), where levels of protection increase with peak blast exposure [27], as well as protection against blast-induced intracranial pressure (ICP) increases and brain strains [30,31]. Although there is increased overall protection against blast exposures, helmet design still has limitations. For example, Zhang et al. [30] demonstrated that blast waves could directly penetrate through the gap between the forehead and the helmet, causing further deformation of padding.

Warfighters who engage in parachute combat rather than ground combat are twice as likely to sustain any form of TBI [32] and are three times more likely to sustain a mild form of a TBI wearing the PASGT combat helmet compared to the ACH [32]. This is likely due to the higher velocity impacts sustained in parachute jumping and a suspension system that is not as advanced as the ACH. The current ACH uses a suspension padding system that offers protection against axonal shearing, but the preclinical models are still limited regarding how effective these padding systems are in humans [26].

Thus, slight modifications to the ACH and/or future helmet design mil-spec testing may reduce the incidence of DAI and the prevalence of military-related TBI for warfighters. Preclinical animal models may provide further adequate preliminary evidence of the need to address diffuse rotational injury associated with warfighters.

Table 3 describes the two military helmets mentioned in this section.

Table 3.

Military Helmets.

4. Current Construction Helmet Design

In the United States, the construction industry is responsible for the largest portion of industrial injuries and induces an estimated healthcare and economic burden of $11.5 billion in direct medical costs and lost wages, as last investigated in 2002 [35]. The United States Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that falls in the construction industry account for 62.9% of all fatal falls [36]. Industrial workers 65 years of age and older are at the greatest risk for more severe outcomes after TBI, including death. In addition, this age group has a higher incidence of falls, and within the construction industry, these workers have the highest (57%) frequency of fall-related injuries, including TBIs. This increased risk for injury demonstrates the importance of proper personal protective equipment (PPE), such as helmets. PPE is defined as a control measure used in hazardous situations where the hazard cannot be eliminated or controlled to an acceptable level through engineering design or administrative actions [37]. According to Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) regulations, all employees and visitors to a construction site must wear a provided hard hat [37]. These industrial safety helmets are required in conditions where objects might fall from above and strike workers on the head, workers may bump their heads against objects, or there is possible contact with electrical hazards. The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) regulates hard hats by setting performance and requirement testing standards. Type I and II helmets reduce force to the top of the head, while type III classified helmets can reduce impact to the top and sides of the head. Industrial safety helmets have a suspension design that is intended to reduce the force of impact and penetrations of small objects. Furthermore, a study was performed to assess their effectiveness against larger objects and found these helmets were capable of reducing the force and linear acceleration for vertical impact [36,37,38]. They also reduced the likelihood of skull fracture and severe injury, further supporting the importance of industrial safety helmets.

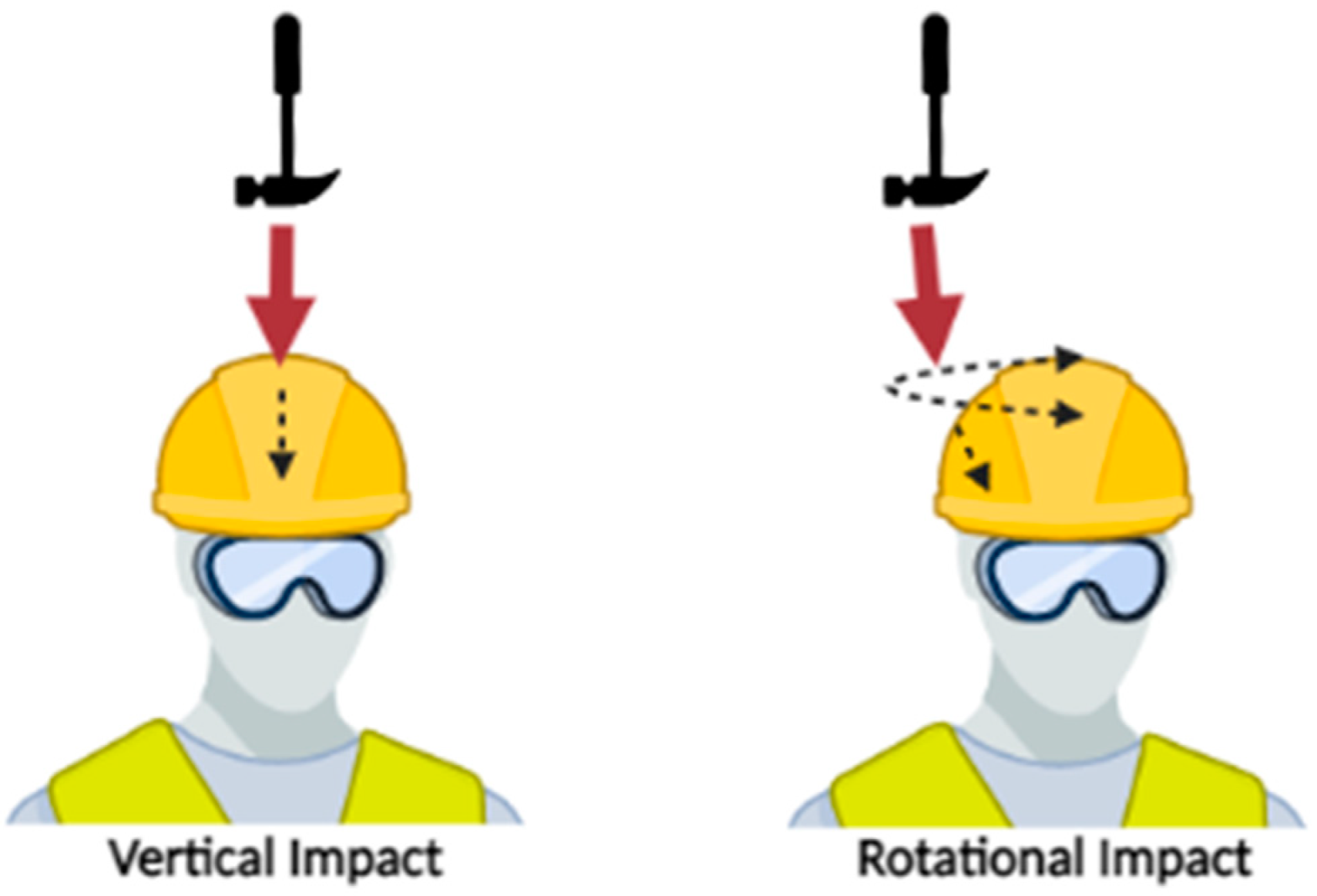

Construction-related injuries to the head can result in skull fractures and localized underlying brain injury, closed head injuries, neck injuries, and rotational injuries leading to diffuse axonal injury [39]. A study was performed to assess the impact of hard hats during varied neck movements utilizing surface electromyography sensors on the upper trapezius muscles of volunteer subjects [40]. The researchers demonstrated that muscle activity and fatigue were not increased while wearing an industrial hard hat, suggesting that this protective equipment is not causing further detriment to workers’ neck strain [40]. Vertical impact occurs in 36% of falling object cases, yet most injuries include a rotational injury [39]. Though industrial safety helmets are required PPE in the construction industry, these helmets have suspension designs that primarily protect against vertical impact. This design may be beneficial for many types of possible injury at a construction site, but it does not protect the wearer during a fall or when faced with a rotational injury (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Industrial safety helmets have a suspension design that prevents injury from vertical impact. These helmets are not designed to prevent injury from side or rotational impacts that would increase injury severity and diffuse axonal injury.

Finite element analysis is a numerical analysis technique utilized to assess the engineering and design of helmets by mathematically modeling physical contributions such as force. This mathematical modeling utilizes a scoring system such as the head injury criteria (HIC) score, incorporating acceleration and time, where a score of 1000 is considered a safe limit [41]. This widely used score has been utilized to improve and test different helmet materials such as Carbon Fiber and Polyethylene [42]. In addition, finite element analysis can be utilized to assess diffuse axonal injury computationally via von Mises stress [38]. A study evaluating simulation-based impact on construction helmets indicated that a 2 kg cylinder vertical impact has a 50% chance of causing mild diffuse axonal injury, which increases in severity as impact speed increases. However, this study was limited by the lack of modeling any elements of rotational acceleration [38]. This testing provides classifications for helmets for one-time impact, yet industrial helmets regularly endure multiple impacts. One study evaluated the damage and vulnerability induced by repeated impacts on the helmets’ shock absorption performance [43]. An endurance limit was determined for the helmet, where cumulative damage from multiple impacts degraded the shock absorption performance when the impacts were greater than the endurance limit. For example, a type I industrial helmet’s endurance limit was found to be a drop height of 1.22 m [43].

The largest challenge with construction-related safety is workers wearing the industrial safety helmet. Industrial safety helmets have been accused of being too heavy and uncomfortable to wear while working; thus, many workers often choose not to wear helmets when possible. One initiative for promoting wearing helmets on construction sites has been artificial intelligence technology for safety helmet recognition [44]. While improvements in industrial helmet design are needed for comfort and protection against rotational injury, the use of these safety helmets is still effective in protecting the wearer from injury. An analysis of work-related injuries demonstrated that safety helmets meeting current OSHA and ANSI requirements more effectively prevented intracranial injury in comparison to no helmet at all [45].

While helmets can effectively dissipate and reduce impact and acceleration-deceleration forces, they do not entirely prevent energy transfer and the risk of concussion. The pathophysiological consequences of single or repeated concussions while wearing a helmet are needed but present challenges when adapting experiments to translational TBI models. Helmets are designed for human heads and impact based on bipedal kinematics, where common TBI animal models introduce varied head and brain shapes and quadrupedal movement that can change the fundamental dynamics of applied forces, where the temporal and spatial profile of physiological alterations, diffuse axonal injury, and secondary injury sequelae can be influenced.

In conclusion, industrial safety helmets are beneficial for preventing head injury, but there is a large gap in work-related injury research. Mechanistic understanding and appropriate injury models, including rotational acceleration, are required to develop more protective helmets for work-related traumatic brain injuries.

5. Secondary Injury Prevention

While there are likely a plethora of factors that influence TBI, linear and rotational acceleration are two of the most significant. Linear acceleration is believed to produce focal trauma at both coup and contrecoup locations within the brain [46]. Examples of focal injuries include epidural hematomas, skull fractures, and cerebral contusions [46,47]. Conversely, rotational acceleration produces more diffuse trauma within the brain through shearing forces [46,48]. For years, reducing linear acceleration has been one of the primary goals of helmet design. However, it was not until 2018 that the National Operating Committee for Standards in Athletic Equipment updated the criteria to include rotational acceleration in the design of new helmets [49]. In a 2020 evaluation of combat helmets released by the US Army Combat Capabilities Development Command, they demonstrated that while, on average, the Army Advanced Combat Helmet (ACH) produced a statistically significant reduction in linear acceleration compared to no helmet. However, it failed to produce a statistically significant average reduction in rotational acceleration and even increased rotational acceleration at higher force impacts [50]. Consequently, helmet designs in sports and combat have historically neglected to consider rotational acceleration and the resultant more mild traumatic brain injuries (mTBI) such as concussion and subconcusion [7,51].

Rotational acceleration produces axonal shearing, obstructing axonal function, and causing an accumulation of amyloid-beta precursor protein that peaks after 24–48 h [52,53,54]. In addition, shearing and mechanical forces produce plasma membrane instability resulting in potassium leakage and neuronal depolarization [55,56]. As a result, the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate is released and binds NMDA receptors, generating a cycle of potentially neurotoxic hyperexcitation [54,57,58,59]. This drastically elevates intercellular calcium and sodium concentrations and destabilizes mitochondrial function as a vital calcium buffer system within the cell [60,61,62]. As a result, calcium-dependent proteases and lipases are activated and reactive oxygen species production increases, causing oxidative stress within the cell [63,64]. Elevated oxidative stress within the cell is believed to promote perturbation within the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and a subsequent accumulation of unfolded proteins. The unfolded protein response (UPR) initially functions to resolve ER stress through inhibition of protein synthesis and proteolysis of misfolded or unfolded proteins [65,66]. With a failure of ER stress resolution over time, the ER UPR pathway ultimately upregulates caspases and pro-apoptotic pathways, promoting cell death [65,67,68,69]. These functions can be exacerbated with repeated injury, and may be targeted for helmet innovation.

6. Innovations in Helmet Design

While the outward appearance of many helmets may not change with safety innovations, the internal design continues to dramatically transform with each new development. The NFL launched its Helmet Challenge in November 2019, with the top-performing prototypes being announced in 2021 [70]. The NFL awarded grants to Kollide, Xenith, and Impressio based on prototype NFL lab performance testing that surpassed the current NFL top-performing helmet [70]. Kollide used a 3D printed helmet containing a 95 pad mesh liner [71]. The 3D printed design allowed for unique customization of the shape of each player’s head [72,73]. Xenith combined a 3D printed polymer lattice with fitted foam inserts [70]. Impressio’s helmet prototype contains liquid crystal elastomers housed within 3D printed columns [71,74]. Liquid crystal elastomers combine the self-organization of the liquid crystalline phase with the elasticity of an elastomer, offering an innovative and potentially superior approach to absorbing impact energy [75,76,77]. All three companies incorporated 3D printing into their design with an increased focus on the customization of helmet fit for each individual. Experimental evaluation is ongoing.

The overall benefit of impact sensors (accelerometer and gyroscope) in helmets has been widely debated, as numerous studies have highlighted the significant error in data measurement and consequently limited clinical utility [78,79]. The 2017 Berlin Concussion in Sport Group concluded that head impact sensors did not offer any beneficial information in diagnosing a concussion [80]. More recent research into developing more accurate impact sensors in helmet and mouthpieces have offered some insight into the duration, direction, magnitude of head motion, and impact [81]. One study examining the use of fiber optics sensors coupled with a machine learning model could accurately predict (R2∼0.90) blunt-force trauma magnitude and direction from novel impacts not yet experienced by the system [82]. When examining angular acceleration and velocity, using a sensor patch placed against the neck has shown some promise in the prediction of head rotational kinematics (R2 > 0.9) [83]. Such a device could be used in conjunction with a helmet sensor to reduce measurement error. Unfortunately, many helmets and patch impact sensors tend to overpredict linear and rotational acceleration with false positive high acceleration impacts [84]. Without visual confirmation of the motion to support the recorded data, this high false positive rate limits the benefit of current impact sensors in practice. As technology advances in the field of impact sensors and analysis of kinetic data, helmet, patch, and mouthpiece sensors may offer valuable information to future clinicians.

For military paratroopers and civilian parachute enthusiasts, parachute opening shock has been associated with the incidence of neck and back injuries [85]. Wing loading, referring to the ratio of weight carried by the individual to the area of the parachute canopy, is believed to affect head acceleration responsible for these injuries [85]. NASA has worked to reduce water landing neck injuries by developing an Orion helmet support assembly (HSA) to mitigate dynamic loading on the neck [86,87]. Their preliminary design was composed of a rigid HSA secured to the helmet with a metal bar braced behind the shoulders [86]. The metal bar was fixed in place by shoulder straps [86]. With dynamic impact testing, this rigid HSA design demonstrated overall increased upper neck loading with an elevated neck injury metric [86]. This data led to the development of a flexible HSA consisting of steel wires attached to both the front and back of the helmet [86]. These interconnected steel wires were bent to fit the chest and back of the wearer, with a shoulder harness attached to the helmet [86]. Overall, NASA’s flexible HSA design demonstrated reduced neck loading and neck injury metrics with testing across various body types [86]. This data suggests that a helmet neck support system may reduce neck injuries in astronauts and potentially paratroopers, while an overly rigid HSA could induce further injury. While protection typically comes with a trade-off of lost mobility, this study indicates that limited mobility may provide some benefit in the reduction of injury.

7. Conclusions, Future Directions

Considering the effectiveness of helmets in preventing catastrophic TBIs, efforts can be made to promote greater helmet usage and awareness. For example, in India, which has a large number of TBIs related to road accidents, public efforts to promote helmet usage and improved prehospital EMS care resulted in plateauing in road traffic deaths [88]. A systematic review of helmet laws found helmet laws to increase compliance and decrease road traffic-related head injuries and fatalities [89]. This is an important consideration in low-income nations, where many people, including pediatric populations, rely on motorcycles, scooters, and bicycles [89]. Certain sports, such as equestrian-related sports, feature low helmet usage and high rates of TBI, so increasing awareness and promotion of helmet use and mandatory helmet laws could also prevent TBIs by up to 50% [90,91]. Other efforts include educating people about replacing helmets within 5–10 years of use, especially when there are signs of cracking and shell/liner damage [92].

Nonetheless, as described in this review, current helmets may not be effective in preventing concussions or mild TBIs [2,7]. This has promoted the development of various new helmets incorporating rotational acceleration testing and rotational damping technology that may decrease concussion incidence or magnitude [93,94,95,96]. For example, Hoshizaki et al. [93] employed drops onto a 45° anvil to simulate the rotational dynamics of head impacts, showing that two helmets (WAVECEL and MIPS) fitted with rotational damping technologies better mitigated rotational acceleration compared to a standard helmet. DiGiacomo et al. [94] similarly used drops onto a 45° anvil to show that rotational damping-based snow helmets significantly reduce rotational acceleration and concussion probability compared to standard helmets. The WAVECEL bicycle helmet uses a compressible cellular structure to provide rotational suspension and has demonstrated significant mitigation of rotational acceleration in 45° anvil drops [95]. It is an extension of prior research by Hansen et al. on an Angular Impact Mitigation (AIM) system consisting of an aluminum honeycomb liner elastically suspended between an inner liner and outer shell, which was shown to reduce linear and angular acceleration, neck loading, and concussion and DAI risk [96]. Similarly, the Multi-Directional Impact Protection System (MIPS) is a slip liner (compared to the standard expanded polystyrene foam bicycle helmet liner) that covers the inside of a helmet to allow for head-helmet sliding during collisions, and also demonstrates significant rotational acceleration mitigation [95]. Another helmet technology involves airbag expansion based on impact sensors, and also demonstrates promising brain injury mitigation results [97,98]. MIPS, WAVECEL, and airbag (Hövding) helmets also reduce brain strain in important regions, according to computational analysis [95,99]. However, these rotational damping technologies do not appear to effectively prevent brain injuries with industrial helmets [100]. More testing of the different rotational damping helmets is necessary to see which provides the most effective protection against concussions in different settings and at different impact locations. Further examination of impact location can inform optimization of padding placement to minimize rotational angular acceleration in more vulnerable locations [99,101]. For example, Fanton et al. [101] found mandibular impacts to be the most significant. Other important metrics to continue to evaluate in helmet testing include the effect of helmet liners in simulating head sliding during impacts, along with cadaveric testing of scalp friction to design better headforms for future studies [49]. Models for assessing helmet design often utilize crash dummies with a rigid spine and do not allow for realistic evaluations of vertical impact on neck injury. Improvements in performance testing have resulted from the use of flexible neck dummies that can better emulate neck compression and rotational impact [39]. These measures should be considered in the development of new safety helmets [39].

Work done at Virginia Tech has focused on rating helmets to help consumers select the safest helmets, which will likely lead manufacturers to continue improving helmet design, better preventing TBIs and concussions [102,103,104]. The STAR evaluation system incorporates a variety of rotational and linear head acceleration testing into helmet ratings, and weighs results by frequency of particular impacts in the given activity, including football, hockey, and cycling [102,103,104]. Extending STAR based systems to evaluate helmets in other sports and activities, including construction and military, will likely result in further development of safer helmets.

Now that rotational acceleration is becoming a vital consideration of helmet testing, further testing and models to correlate head kinematics (particularly rotational acceleration) with brain strain will be important [105,106,107]. For example, Ghazi et al. [108] developed a convolutional neural network that approximates brain strain and demonstrated significant variations in brain strains between 23 football helmet models, suggesting continued room for improvement in helmet design. Future helmets might use such data to initiate warnings in helmets when concussion is probable [7]. Other efforts to reduce concussions and improve helmets include standardizing definitions of concussion by using protocols involving eye-tracking assessments and/or serum biomarkers (such as total tau, STAT3 pathway proteins, and glial fibrillary acid protein) to better analyze and differentiate data in future helmet studies [2,109,110]. Perhaps helmet selection will evolve to increased selection based on multiple contexts and sports-related risks due to technological innovations and assessment of impact kinematics. Nonetheless, more helmet research considering rotational acceleration will likely advance the field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.L.-W.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G., J.G., Z.S., T.C., M.W., J.W. and T.C.T.; writing—review and editing, M.G. and B.L.-W.; supervision, M.G. and B.L.-W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bruns, J., Jr.; Hauser, W.A. The epidemiology of traumatic brain injury: A review. Epilepsia 2003, 44, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sone, J.Y.; Kondziolka, D.; Huang, J.H.; Samadani, U. Helmet efficacy against concussion and traumatic brain injury: A review. J. Neurosurg. 2017, 126, 768–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnan, J.; Walsh, S.; Fortin, Y.; Gaskin, J.; Sikora, L.; Morrissey, A.; Collins, K.; MacDonald, D. Factors associated with the onset and progression of neurotrauma: A systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Neurotoxicology 2017, 61, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.C.; Rivara, F.P.; Thompson, R. Helmets for preventing head and facial injuries in bicyclists. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2000, 1999, Cd001855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Brand, C.L.; Karger, L.B.; Nijman, S.T.M.; Valkenberg, H.; Jellema, K. Bicycle Helmets and Bicycle-Related Traumatic Brain Injury in the Netherlands. Neurotrauma Rep. 2020, 1, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, D.C.; Rivara, F.P.; Thompson, R.S. Effectiveness of Bicycle Safety Helmets in Preventing Head Injuries: A Case-Control Study. JAMA 1996, 276, 1968–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoshizaki, T.B.; Post, A.; Oeur, R.A.; Brien, S.E. Current and Future Concepts in Helmet and Sports Injury Prevention. Neurosurgery 2014, 75, S136–S148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurdjian, E.S.; Webster, J.E.; Lissner, H.R. Observations on the mechanism of brain concussion, contusion, and laceration. Surg. Gynecol. Obs. 1955, 101, 680–690. [Google Scholar]

- Cantu, R.C. Neurologic Athletic Head and Spine Injuries; W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Post, A.; Hoshizaki, T.B. Mechanisms of brain impact injuries and their prediction: A review. Trauma 2012, 14, 327–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, A.C.; Meaney, D.F. Tissue-level thresholds for axonal damage in an experimental model of central nervous system white matter injury. J. Biomech. Eng. 2000, 122, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, M.A.F.; Cui, L.; Gilchrist, M.D. Finite element modelling of equestrian helmet impacts exposes the need to address rotational kinematics in future helmet designs. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2011, 14, 1021–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoshizaki, T.; Brien, S. The Science and Design of Head Protection in Sport. Neurosurgery 2004, 55, 956–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntosh, A.S.; Andersen, T.E.; Bahr, R.; Greenwald, R.; Kleiven, S.; Turner, M.; Varese, M.; McCrory, P. Sports helmets now and in the future. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 1258–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Post, A.; Hoshizaki, T.B.; Brien, S. Head Injuries, Measurement Criteria and Helmet Design. In Routledge Handbook of Ergonomics in Sport and Exercise; Hong, Y., Ed.; Routledge Publishers: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, M.C.; Bruneau, D.; Barker, J.B.; Gierczycka, D.; Coralles, M.A.; Cronin, D.S. Component-Level Finite Element Model and Validation for a Modern American Football Helmet. J. Dyn. Behav. Mater. 2019, 5, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuna, E.B.; Ozel, E. Factors Affecting Sports-Related Orofacial Injuries and the Importance of Mouthguards. Sports Med. 2014, 44, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranalli, D.N.; Demas, P.N. Orofacial Injuries from Sport. Sports Med. 2002, 32, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, L.; Jermy, M.; Eloi, P.; Cornillon, G. Helmet position, ventilation holes and drag in cycling. Sports Eng. 2015, 18, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, T.J.; Thai, K. Helmet Protection against Basilar Skull Fracture; Australian Transport Safety Bureau: Canberra, Australian, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Which Helmet for Which Activity? Available online: https://www.cpsc.gov/safety-education/safety-guides/sports-fitness-and-recreation-bicycles/which-helmet-which-activity (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- International Cricket Council. Available online: https://www.icc-cricket.com/homepage (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Standard Specification for Headgear Used in Soccer. Available online: https://www.astm.org/f2439-17e01.html (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Scharine, A.A.; Binseel, M.S.; Mermagen, T.; Letowski, T.R. Sound localisation ability of soldiers wearing infantry ACH and PASGT helmets. Ergonomics 2014, 57, 1222–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, S.; Edwards, E.D.; Jesunathadas, M.; Landry, T.; Piland, S.G.; Plaisted, T.A.; Kleinberger, M.; Gould, T.E. Influence of Friction at the Head-Helmet Interface on Advanced Combat Helmet (ACH) Blunt Impact Kinematic Performance. Mil. Med. 2022, usab547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradfield, C.; Vavalle, N.; DeVincentis, B.; Wong, E.; Luong, Q.; Voo, L.; Carneal, C. Combat Helmet Suspension System Stiffness Influences Linear Head Acceleration and White Matter Tissue Strains: Implications for Future Helmet Design. Mil. Med. 2018, 183, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpsma, R.; Carlsen, R.W.; Szalkowski, R.; Malave, S.; Fawzi, A.L.; Franck, C.; Hovey, C. Head Impact Modeling to Support a Rotational Combat Helmet Drop Test. Mil. Med. 2021, usab374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begonia, M.; Humm, J.; Shah, A.; Pintar, F.A.; Yoganandan, N. Influence of ATD versus PMHS reference sensor inputs on computational brain response in frontal impacts to advanced combat helmet (ACH). Traffic Inj. Prev. 2018, 19, S159–S161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grujicic, M.; Bell, W.C.; Pandurangan, B.; Glomski, P.S. Fluid/Structure Interaction Computational Investigation of Blast-Wave Mitigation Efficacy of the Advanced Combat Helmet. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2011, 20, 877–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Makwana, R.; Sharma, S. Brain response to primary blast wave using validated finite element models of human head and advanced combat helmet. Front. Neurol. 2013, 4, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyein, M.K.; Jason, A.M.; Yu, L.; Pita, C.M.; Joannopoulos, J.D.; Moore, D.F.; Radovitzky, R.A. In silico investigation of intracranial blast mitigation with relevance to military traumatic brain injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 20703–20708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivins, B.J.; Crowley, J.S.; Johnson, J.; Warden, D.L.; Schwab, K.A. Traumatic brain injury risk while parachuting: Comparison of the personnel armor system for ground troops helmet and the advanced combat helmet. Mil. Med. 2008, 173, 1168–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, C.; Tan, V.; Lee, H.-P. Ballistic impact of a KEVLAR® helmet: Experiment and simulations. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2008, 35, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilisik, A.K.; Turhan, Y. Multidirectional stitched layered aramid woven fabric structures and their experimental characterization of ballistic performance. Text. Res. J. 2009, 79, 1331–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waehrer, G.M.; Dong, X.S.; Millera, T.; Haile, E.; Men, Y. Costs of occupational injuries in construction in the United States. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2007, 39, 1258–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/ (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- 1926.100—Head Protection. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Available online: https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardnumber/1926/1926.100 (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Long, J.; Yang, J.; Lei, Z.; Liang, D. Simulation-based assessment for construction helmets. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 18, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, A.; Mills, N.J.; Gilchrist, A. Industrial Head Injuries and the Performance of the Helmets. 1995. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Industrial-head-injuries-and-the-performance-of-Hulme-Mills/03bf8f6afc4729f9529ce630daed14473b11ecb8 (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Magnuson, S.; Autenrieth, D.A.A.; Stack, T.; Risser, S.; Gilkey, D. Are hard hats a risk factor for WRMSD in the cervical-thoracic region? Work Read. Mass. 2020, 66, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Z.; Pan, C.S.; Wimer, B.M.; Rosen, C.L. Finite element simulations of the head-brain responses to the top impacts of a construction helmet: Effects of the neck and body mass. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H J. Eng. Med. 2017, 231, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naresh, P.; Krishnudu, D.M.; Babu, A.H.; Hussain, P. Design And Analysis of Industrial Helmet. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Res. 2015, 5, 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.Z.; Pan, C.S.; Wimer, B.M. Evaluation of the shock absorption performance of construction helmets under repeated top impacts | Elsevier Enhanced Reader. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2019, 96, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Cheng, M.; Feng, M.; Lijuan, Z. Research on Recognition of Safety Helmet Wearing of Electric Power Construction Personnel Based on Artificial Intelligence Technology. IOP Sci. 2020, 1684, 012013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.C.; Ro, Y.S.; Shin, S.D.; Kim, J.Y. Preventive Effects of Safety Helmets on Traumatic Brain Injury after Work-Related Falls. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tierney, G. Concussion biomechanics, head acceleration exposure and brain injury criteria in sport: A review. Sports Biomech. 2021, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiven, S. Why Most Traumatic Brain Injuries are Not Caused by Linear Acceleration but Skull Fractures are. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2013, 1, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowson, S.; Bland, M.L.; Campolettano, E.T.; Press, J.N.; Rowson, B.; Smith, J.A.; Sproule, D.W.; Tyson, A.M.; Duma, S.M. Biomechanical Perspectives on Concussion in Sport. Sports Med. Arthrosc. Rev. 2016, 24, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotta, A.; Annaidh, A.N.; Burek, R.O.; Pelgrims, B.; Ivens, J. Evaluation of the head-helmet sliding properties in an impact test. J. Biomech. 2018, 75, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neice, R.; Plaisted, T. Evaluation of a Combat Helmet Under Combined Translational and Rotational Impact Loading. 2020. Available online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/AD1120852 (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- McKeithan, L.; Hibshman, N.; Yengo-Kahn, A.M.; Solomon, G.S.; Zuckerman, S.L. Sport-Related Concussion: Evaluation, Treatment, and Future Directions. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamjoom, A.A.B.; Rhodes, J.; Andrews, P.J.D.; Grant, S.G.N. The synapse in traumatic brain injury. Brain 2020, 144, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlovic, D.; Pekic, S.; Stojanovic, M.; Popovic, V. Traumatic brain injury: Neuropathological, neurocognitive and neurobehavioral sequelae. Pituitary 2019, 22, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romeu-Mejia, R.; Giza, C.C.; Goldman, J.T. Concussion Pathophysiology and Injury Biomechanics. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2019, 12, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, C.E.; Cullen, D.K. Mechanosensation in traumatic brain injury. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021, 148, 105210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wofford, K.L.; Grovola, M.R.; Adewole, D.O.; Browne, K.D.; Putt, M.E.; O’Donnell, J.C.; Cullen, D.K. Relationships between injury kinematics, neurological recovery, and pathology following concussion. Brain Commun. 2021, 3, fcab268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehse, J.; Taghibiglou, C. The overlooked aspect of excitotoxicity: Glutamate-independent excitotoxicity in traumatic brain injuries. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2019, 49, 1157–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerriero, R.M.; Giza, C.C.; Rotenberg, A. Glutamate and GABA Imbalance Following Traumatic Brain Injury. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2015, 15, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wofford, K.L.; Loane, D.J.; Cullen, D.K. Acute drivers of neuroinflammation in traumatic brain injury. Neural Regen. Res. 2019, 14, 1481–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, W.B.; Joseph, B.; Spry, M.; Vekaria, H.J.; Saatman, K.E.; Sullivan, P.G. Acute Mitochondrial Impairment Underlies Prolonged Cellular Dysfunction after Repeated Mild Traumatic Brain Injuries. J. Neurotrauma 2019, 36, 1252–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Kong, R.-H.; Zhang, L.-M.; Zhang, J.-N. Mitochondria in traumatic brain injury and mitochondrial-targeted multipotential therapeutic strategies. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 167, 699–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verweij, B.H.; Muizelaar, J.P.; Vinas, F.C.; Peterson, P.L.; Xiong, Y.; Lee, C.P. Impaired cerebral mitochondrial function after traumatic brain injury in humans. J. Neurosurg. 2000, 93, 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, H.; Shakkour, Z.; Tabet, M.; Abdelhady, S.; Kobaisi, A.; Abedi, R.; Nasrallah, L.; Pintus, G.; Al-Dhaheri, Y.; Mondello, S.; et al. Traumatic Brain Injury: Oxidative Stress and Novel Anti-Oxidants Such as Mitoquinone and Edaravone. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahel, D.K.; Kaira, M.; Raj, K.; Sharma, S.; Singh, S. Mitochondrial dysfunctioning and neuroinflammation: Recent highlights on the possible mechanisms involved in Traumatic Brain Injury. Neurosci. Lett. 2019, 710, 134347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, R.D.; Bird, S.; Sun, M.; Yamakawa, G.R.; Major, B.P.; Mychasiuk, R.; O’Brien, T.J.; McDonald, S.J.; Shultz, S.R. Activation of the Protein Kinase R–Like Endoplasmic Reticulum Kinase (PERK) Pathway of the Unfolded Protein Response after Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury and Treatment with a PERK Inhibitor. Neurotrauma Rep. 2021, 2, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheper, W.; Hoozemans, J.J.M. The unfolded protein response in neurodegenerative diseases: A neuropathological perspective. Acta Neuropathol. 2015, 130, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, K.; Laskowitz, D.T. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Secondary Neuronal Injury. In Translational Research in Traumatic Brain Injury; Laskowitz, D., Grant, G., Eds.; CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hetz, C.; Axten, J.M.; Patterson, J.B. Pharmacological targeting of the unfolded protein response for disease intervention. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2019, 15, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Xu, W.; Reed, J.C. Cell death and endoplasmic reticulum stress: Disease relevance and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 1013–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NFL Helmet Challenge Raises the Bar for Helmet Technology and Performance, Awards $1.55 Million in Grant Funding to Help New Models Get on Field Faster. Available online: https://www.nfl.com/playerhealthandsafety/equipment-and-innovation/innovation-challenges/nfl-helmet-challenge-raises-the-bar-for-helmet-technology-and-performance-awards (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Video: Meet the Awardees of the NFL Helmet Challenge. Available online: https://www.nfl.com/playerhealthandsafety/equipment-and-innovation/innovation-challenges/video-meet-the-awardees-of-the-nfl-helmet-challenge (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- 3 Ingenious innovations from the NFL’s Helmet Challenge. Available online: https://epicapplications.com/3-ingenious-innovations-from-the-nfls-helmet-challenge/ (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- KOLLIDE. Kollide: A 3D Revolution Is Coming. Available online: https://www.kollide.ca/ (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Chatham, L. Protection & Testing Impressio Tech. Available online: https://www.impressio.tech/human-protection (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Hussain, M.; Jull, E.I.L.; Mandle, R.J.; Raistrick, T.; Hine, P.J.; Gleeson, H.F. Liquid Crystal Elastomers for Biological Applications. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Chung, C.; Traugutt, N.A.; Yakacki, C.M.; Long, K.N.; Yu, K. 3D Printing of Liquid Crystal Elastomer Foams for Enhanced Energy Dissipation Under Mechanical Insult. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 12698–12708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.-Y.; Shen, B.; Traugutt, N.A.; Zhu, Z.; Fang, L.; Yakacki, C.M.; Nguyen, T.D.; Kang, S.H. Synergistic Energy Absorption Mechanisms of Architected Liquid Crystal Elastomers. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2200272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, K.L.; Rowson, S.; Duma, S.M.; Broglio, S.P. Head-Impact-Measurement Devices: A Systematic Review. J. Athl. Train. 2017, 52, 206–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummiskey, B.; Schiffmiller, D.; Talavage, T.M.; Leverenz, L.; Meyer, J.J.; Adams, D.; Nauman, E.A. Reliability and accuracy of helmet-mounted and head-mounted devices used to measure head accelerations. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part P J. Sports Eng. Technol. 2017, 231, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L. Sports concussions: Can head impact sensors help biomedical engineers to design better headgear? Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 370–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabler, L.F.; Dau, N.Z.; Park, G.; Miles, A.; Arbogast, K.B.; Crandall, J.R. Development of a Low-Power Instrumented Mouthpiece for Directly Measuring Head Acceleration in American Football. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 49, 2760–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Han, T.; O’Malley, R.; Kumar, A.; Gerald, R.E.; Huang, J. Fiber optic sensor embedded smart helmet for real-time impact sensing and analysis through machine learning. J. Neurosci. Methods 2021, 351, 109073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dsouza, H.; Pastrana, J.; Figueroa, J.; Gonzalez-Afanador, I.; Davila-Montero, B.M.; Sepúlveda, N. Flexible, self-powered sensors for estimating human head kinematics relevant to concussions. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eitzen, I.; Renberg, J.; Færevik, H. The Use of Wearable Sensor Technology to Detect Shock Impacts in Sports and Occupational Settings: A Scoping Review. Sensors 2021, 21, 4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooks, T.F.M.S.; Novotny, B.L.M.S.; McGovern, S.M.B.S.; Winegar, A.; Shivers, B.L.P.; Brozoski, F.T.M.S. Evaluation of Head and Body Kinematics Experienced During Parachute Opening Shock. Mil. Med. 2021, 186, e1149–e1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhey, J.; Gohmert, D.; Jacobs, S.; Baldwin, M.A. Development of a Novel Helmet Support Assembly for NASA Orion Crew Survival Suit. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Environmental Systems, Boston, MA, USA, 7 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, S.; Tufts, D.; Gohmert, D. Space Suit Development for Orion. In Proceedings of the 48th International Conference on Environmental Systems, Albuquerque, NM, USA, 8–12 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Veerappan, V.R.; Nagendra, B.; Thalluri, P.; Manda, V.S.; Rao, R.N.; Pattisapu, J.V. Reducing the Neurotrauma Burden in India—A National Mobilization. World Neurosurg. 2022, 165, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, R.Y.; LoPresti, M.A.; García, R.M.; Lam, S. Primary prevention of road traffic accident–related traumatic brain injuries in younger populations: A systematic review of helmet legislation. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. PED 2020, 25, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkler, E.A.; Yue, J.K.; Burke, J.F.; Chan, A.K.; Dhall, S.S.; Berger, M.S.; Manley, G.T.; Tarapore, P.E. Adult sports-related traumatic brain injury in United States trauma centers. Neurosurg. Focus FOC 2016, 40, E4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuckerman, S.L.; Morgan, C.D.; Burks, S.; Forbes, J.A.; Chambless, L.B.; Solomon, G.S.; Sills, A.K. Functional and Structural Traumatic Brain Injury in Equestrian Sports: A Review of the Literature. World Neurosurg. 2015, 83, 1098–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commission, C.P.S. Which Helmet for Which Activity? Available online: https://www.cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/349-WhichHelmetBrochure_5-13-22_WEB_508_0.pdf?VersionId=ugCUjMcQ5AAwOtgdO2UkkC8nCfGRRMwW (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Hoshizaki, T.; Post, A.M.; Zerpa, C.E.; Legace, E.; Hoshizaki, T.B.; Gilchrist, M.D. Evaluation of two rotational helmet technologies to decrease peak rotational acceleration in cycling helmets. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiGiacomo, G.; Tsai, S.; Bottlang, M. Impact Performance Comparison of Advanced Snow Sport Helmets with Dedicated Rotation-Damping Systems. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 49, 2805–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliven, E.; Rouhier, A.; Tsai, S.; Willinger, R.; Bourdet, N.; Deck, C.; Madey, S.M.; Bottlang, M. Evaluation of a novel bicycle helmet concept in oblique impact testing. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2019, 124, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, K.; Dau, N.; Feist, F.; Deck, C.; Willinger, R.; Madey, S.M.; Bottlang, M. Angular Impact Mitigation system for bicycle helmets to reduce head acceleration and risk of traumatic brain injury. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2013, 59, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, M.; Laksari, K.; Kuo, C.; Grant, G.A.; Camarillo, D.B. Modeling and Optimization of Airbag Helmets for Preventing Head Injuries in Bicycling. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 45, 1148–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, K.M.; Holder, D. A Biomechanical Evaluation of a Novel Airbag Bicycle Helmet Concept for Traumatic Brain Injury Mitigation. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abayazid, F.; Ding, K.; Zimmerman, K.; Stigson, H.; Ghajari, M. A New Assessment of Bicycle Helmets: The Brain Injury Mitigation Effects of New Technologies in Oblique Impacts. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 49, 2716–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottlang, M.; DiGiacomo, G.; Tsai, S.; Madey, S. Effect of helmet design on impact performance of industrial safety helmets. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanton, M.G.; Sganga, J.A.; Camarillo, D. Vulnerable locations on the head to brain injury and implications for helmet design. J. Biomech. Eng. 2019, 141, 121002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowson, S.; Duma, S.M. Development of the STAR evaluation system for football helmets: Integrating player head impact exposure and risk of concussion. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2011, 39, 2130–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowson, B.; Rowson, S.; Duma, S.M. Hockey STAR: A Methodology for Assessing the Biomechanical Performance of Hockey Helmets. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 43, 2429–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bland, M.L.; McNally, C.; Zuby, D.S.; Mueller, B.C.; Rowson, S. Development of the STAR Evaluation System for Assessing Bicycle Helmet Protective Performance. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 48, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, K.; Mao, H. Mechanisms and variances of rotation-induced brain injury: A parametric investigation between head kinematics and brain strain. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2020, 19, 2323–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabler, L.F.; Crandall, J.R.; Panzer, M.B. Development of a Second-Order System for Rapid Estimation of Maximum Brain Strain. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 47, 1971–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.E.; Urban, J.E.; Espeland, M.A.; Walkup, M.P.; Holcomb, J.M.; Davenport, E.M.; Powers, A.K.; Whitlow, C.T.; Maldjian, J.A.; Stitzel, J.D. Cumulative strain-based metrics for predicting subconcussive head impact exposure-related imaging changes in a cohort of American youth football players. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2022, 29, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghazi, K.; Begonia, M.; Rowson, S.; Ji, S. American Football Helmet Effectiveness Against a Strain-Based Concussion Mechanism. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giza, C.C.; McCrea, M.; Huber, D.; Cameron, K.L.; Houston, M.N.; Jackson, J.C.; McGinty, G.; Pasquina, P.; Broglio, S.P.; Brooks, A.; et al. Assessment of Blood Biomarker Profile After Acute Concussion During Combative Training Among US Military Cadets: A Prospective Study From the NCAA and US Department of Defense CARE Consortium. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2037731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorn, R.; Mithani, S.; Devoto, C.; Meier, T.B.; Lai, C.; Yun, S.; Broglio, S.P.; McAllister, T.W.; Giza, C.C.; Kim, H.S.; et al. Proteomic Profiling of Plasma Biomarkers Associated With Return to Sport Following Concussion: Findings From the NCAA and Department of Defense CARE Consortium. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 901238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).