Experiences of Adolescents Living with HIV on Transitioning from Pediatric to Adult HIV Care in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis

Abstract

1. Introduction

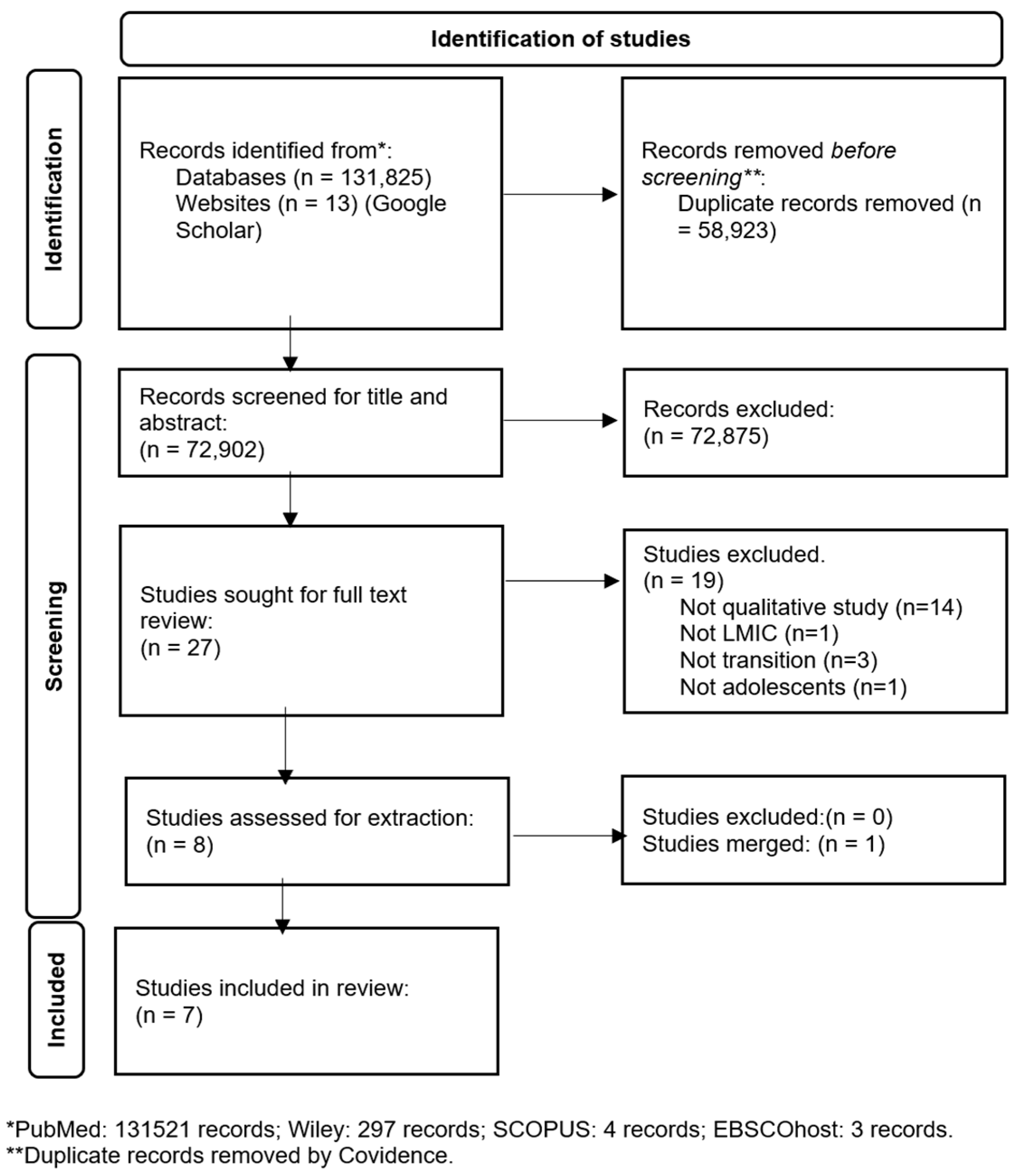

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Registration

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion Criteria and Study Selection

2.4. Sampling of Studies

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Assessment of Individual Study Quality

2.7. Data Management, Analysis, and Synthesis

3. Results

| Author, Year | Title | Country | Study Design | Data Collection Method | Data Analysis Method | Study Population | Number of Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abaka and Nutor 2021 [40] | Transitioning from pediatric to adult care and the HIV care continuum in Ghana: a retrospective study | Ghana | Descriptive exploratory | Semi-structured in-depth interviews and field notes | Thematic content analysis | ALHIVs, 13–18 years | 10 |

| Agambire et al., 2022 [41] | Adolescent on the bridge: Transitioning adolescents living with HIV to an adult clinic, in Ghana, to go or not to go? | Ghana | Exploratory | Semi-structured interviews | Thematic analysis | ALHIVs, 13–19 years enrolled in HIV care | 13 |

| Ashaba et al., 2022 [18] | Challenges and fears of adolescents and young adults living with HIV facing transition to adult HIV care | Uganda | Descriptive qualitative | Individual, in-depth interviews | Thematic content analysis | ALHIVs 15–19 years, young adults living with HIV, 20–24 years, caregivers, and healthcare providers | 10 |

| Katusiime et al., 2013 [42] | Transitioning behaviorally infected HIV-positive young people into adult care: Experiences from the young person’s point of view | Uganda | Retrospective evaluation | Open-ended group discussion | Thematic content analysis | Young people living with HIV YPLHIV 15–24 years | 30 |

| Masese et al., 2019 [39] | Challenges and facilitators of transition from adolescent to adult HIV care among young adults living with HIV in Moshi, Tanzania | Tanzania | Descriptive qualitative | In-depth interviews | Grounded theory | Young adults living with HIV. Age not reported | 20 |

| Pinzón-Iregui et al., 2017 [14] | “... like because you are a grownup, you do not need help”: Experiences of Transition from Pediatric to Adult Care among Youth with Perinatal HIV Infection, Their Caregivers, and Health Care Providers in the Dominican Republic | Dominican Republic | Exploratory qualitative | Focus groups | Grounded theory and phenomenological approach | Youth with perinatal HIV infection, caregivers, and healthcare providers. Age not reported | 15 |

| Zanoni et al., 2021 [5] | ‘It was not okay because you leave your friends behind’: A prospective analysis of transition to adult care for adolescents living with perinatally-acquired HIV in South Africa | South Africa | Mixed methods | In-depth qualitative interviews with open-ended questions | Descriptive analysis (quantitative data) and inductive analysis (qualitative data) | Adolescents living with perinatally acquired HIV. Age not reported | 30 |

3.1. Themes

Pre-Transition (High CERQual)

3.2. Transition Experience (Moderate CERQual Confidence)

3.3. Post-Transition (Moderate CERQual Confidence)

3.4. Individual Barriers (Moderate CERQual Confidence)

3.5. Supportive Environment (Moderate CERQual Confidence)

4. Discussion

5. Limitations of This Study

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- UNICEF. UNAIDS 2021 Estimates. 2021. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/hivaids/global-regional-trends/ (accessed on 29 May 2022).

- UNICEF. 2023 Global Snapshot on HIV and AIDS Progress and priorities for children, adolescents and pregnant women. 2023. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/easterncaribbean/media/5131/file/HIV%202024%20Snapshot.pdf.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Adhiambo, H.F.; Mwamba, C.; Lewis-Kulzer, J.; Iguna, S.; Ontuga, G.M.; Mangale, D.I.; Nyandieka, E.; Nyanga, J.; Opondo, I.; Osoro, J.; et al. Enhancing engagement in HIV care among adolescents and young adults: A focus on phone-based navigation and relationship building to address barriers in HIV care. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2025, 5, e0002830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimbre, M.S.; Bodicha, B.B.; Gabriel, A.N.A.; Ghazal, L.; Jiao, K.; Ma, W. Barriers and facilitators of transition of adolescents living with HIV into adult care in under-resourced settings of Southern Ethiopia: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2800. [Google Scholar]

- Zanoni, B.C.; Archary, M.; Subramony, T.; Sibaya, T.; Psaros, C.; Haberer, J.E. ‘It was not okay because you leave your friends behind’: A prospective analysis of transition to adult care for adolescents living with perinatally-acquired HIV in South Africa. Vulnerable Child. Youth Stud. 2021, 16, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbebe, S.; Rabie, S.; Coetzee, B.J. Factors influencing the transition from paediatric to adult HIV care in the Western Cape, South Africa: Perspectives of health care providers. Afr. J. AIDS Res. 2023, 22, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, V.; Zaner, S.; Ryscavage, P. HIV healthcare transition outcomes among youth in North America and Europe: A review. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2017, 20, 21490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mark, D.; Taing, L.; Cluver, L.; Collins, C.; Iorpenda, K.; Andrade, C.; Hatane, L. What is it going to take to move youth-related HIV programme policies into practice in Africa? J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2017, 20, 21491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.A.; Tsondai, P.; Tiffin, N.; Eley, B.; Rabie, H.; Euvrard, J.; Orrell, C.; Prozesky, H.; Wood, R.; Cogill, D.; et al. Where do HIV-infected adolescents go after transfer?—Tracking transition/transfer of HIV-infected adolescents using linkage of cohort data to a health information system platform. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2017, 20, 21668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slogrove, A.L.; Mahy, M.; Armstrong, A.; Davies, M.A. Living and dying to be counted: What we know about the epidemiology of the global adolescent HIV epidemic. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2017, 20, 21520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maturo, D.; Powell, A.; Major-Wilson, H.; Sanchez, K.; De Santis, J.P.; Friedman, L.B. Development of a protocol for transitioning adolescents with HIV infection to adult care. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2011, 25, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanyon, C.; Seeley, J.; Namukwaya, S.; Musiime, V.; Paparini, S.; Nakyambadde, H.; Matama, C.; Turkova, A.; Bernays, S. “Because we all have to grow up”: Supporting adolescents in Uganda to develop core competencies to transition towards managing their HIV more independently. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2020, 23, e25552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, H.; Bonnet, K.; Schlundt, D.; Hill, N.; Pierce, L.; Ahonkhai, A.; Desai, N. Mixed Methods Evaluation of a Youth-Friendly Clinic for Young People Living with HIV Transitioning from Pediatric Care. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 9, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinzón-Iregui, M.C.; Ibanez, G.; Beck-Sagué, C.; Halpern, M.; Mendoza, R.M. “…like because you are a grownup, you do not need help”: Experiences of Transition from Pediatric to Adult Care among Youth with Perinatal HIV Infection, Their Caregivers, and Health Care Providers in the Dominican Republic. J. Int. Assoc. Provid. AIDS Care 2017, 16, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahourou, D.L.; Gautier-Lafaye, C.; Teasdale, C.A.; Renner, L.; Yotebieng, M.; Desmonde, S.; Ayaya, S.; Davies, M.-A.; Leroy, V. Transition from paediatric to adult care of adolescents living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges, youth-friendly models, and outcomes. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2017, 20, 21528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiener, L.S.; Kohrt, B.A.; Battles, H.B.; Pao, M. The HIV experience: Youth identified barriers for transitioning from pediatric to adult care. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2011, 36, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashaba, S.; Zanoni, B.C.; Baguma, C.; Tushemereirwe, P.; Nuwagaba, G.; Kirabira, J.; Nansera, D.; Maling, S.; Tsai, A.C. Challenges and Fears of Adolescents and Young Adults Living with HIV Facing Transition to Adult HIV Care. AIDS Behav. 2023, 27, 1189–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashaba, S.; Zanoni, B.C.; Baguma, C.; Tushemereirwe, P.; Nuwagaba, G.; Nansera, D.; Maling, S.M.; Tsai, A.C. Perspectives About Transition Readiness Among Adolescents and Young People Living With Perinatally Acquired HIV in Rural, Southwestern Uganda: A Qualitative Study. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2022, 33, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metje, A.; Shaw, S.; Mugo, C.; Awuor, M.; Dollah, A.; Moraa, H.; Kundu, C.; Wamalwa, D.; John-Stewart, G.; Beima-Sofie, K.; et al. Sustainability of an evidence-based intervention supporting transition to independent care for youth living with HIV in Kenya. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2025, 5, e0004111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighat, R.; Toska, E.; Cluver, L.; Gulaid, L.; Mark, D.; Bains, A. Transition pathways out of pediatric care and associated HIV outcomes for adolescents living with HIV in South Africa. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2019, 82, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, D.M.; Tanner, A.E. Health-care transition from adolescent to adult services for young people with HIV. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchwood, T.D.; Malo, V.; Jones, C.; Metzger, I.W.; Atujuna, M.; Marcus, R.; Conserve, D.F.; Handler, L.; Bekker, L.-G. Healthcare retention and clinical outcomes among adolescents living with HIV after transition from pediatric to adult care: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanoni, B.C.; Sibaya, T.; Cairns, C.; Haberer, J.E. Barriers to Retention in Care are Overcome by Adolescent-Friendly Services for Adolescents Living with HIV in South Africa: A Qualitative Analysis. AIDS Behav. 2019, 23, 957–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sam-Agudu, N.A.; Pharr, J.R.; Bruno, T.; Cross, C.L.; Cornelius, L.J.; Okonkwo, P.; Oyeledun, B.; Khamofu, H.; Olutola, A.; Erekaha, S.; et al. Adolescent Coordinated Transition (ACT) to improve health outcomes among young people living with HIV in Nigeria: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2017, 18, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, A.H.; Vreeman, R.C.; Judd, A. Tracking the transition of adolescents into adult HIV care: A global assessment. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2017, 20, 21878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judd, A.; Davies, M.A. Adolescent transition among young people with perinatal HIV in high-income and low-income settings. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2018, 13, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, T.H.; Wallace, M.L.; Snyder, K.L.; Robson, V.K.; Mabud, T.S.; Kalombo, C.D.; Bekker, L.-G. South African healthcare provider perspectives on transitioning adolescents into adult HIV care. S. Afr. Med. J. 2016, 106, 804–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petinger, C.; Crowley, T.; van Wyk, B. Transition of adolescents from paediatric to adult HIV care in South Africa: A policy review. South. Afr. J. HIV Med. 2025, 26, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petinger, C.; van Wyk, B.; Crowley, T. Mapping the Transition of Adolescents to Adult HIV Care: A Mixed-Methods Perspective from the Cape Town Metropole, South Africa. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petinger, C.; Crowley, T.; van Wyk, B. Experiences of adolescents living with HIV on transitioning from pediatric to adult HIV care in low and middle-income countries: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis Protocol. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0296184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, A.; Smith, D.; Booth, A. Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, H. Purposeful sampling in qualitative research synthesis. Qual. Res. J. 2011, 11, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Systematic Review Checklist. 2022. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (mmat) version 2018 user guide. Educ. Information 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, S.; Booth, A.; Glenton, C.; Munthe-Kaas, H.; Rashidian, A.; Wainwright, M.; Bohren, M.A.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Colvin, C.J.; Garside, R.; et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: Introduction to the series. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett-Page, E.; Thomas, J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: A critical review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2009, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masese, R.V.; Ramos, J.V.; Rugalabamu, L.; Luhanga, S.; Shayo, A.M.; Stewart, K.A.; Cunningham, C.K.; Dow, D.E. Challenges and facilitators of transition from adolescent to adult HIV care among young adults living with HIV in Moshi, Tanzania. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2019, 22, e25406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaka, P.; Nutor, J.J. Transitioning from pediatric to adult care and the HIV care continuum in Ghana: A retrospective study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agambire, R.; McHunu, G.G.; Naidoo, J.R. Adolescent on the bridge: Transitioning adolescents living with HIV to an adult clinic, in Ghana, to go or not to go? PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katusiime, C.; Parkes-Ratanshi, R.; Kambugu, A. Transitioning behaviourally infected HIV positive young people into adult care: Experiences from the young person’s point of view. S. Afr. J. HIV Med. 2013, 14, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Ngin, C.; Pal, K.; Khol, V.; Tuot, S.; Sau, S.; Chhoun, P.; Mburu, G.; Choub, S.C.; Chhim, K.; et al. Transition into adult care: Factors associated with level of preparedness among adolescents living with HIV in Cambodia. AIDS Res. Ther. 2017, 14, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanoni, B.C.; Archary, M.; Sibaya, T.; Musinguzi, N.; Haberer, J.E. Transition from pediatric to adult care for adolescents living with HIV in South Africa: A natural experiment and survival analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakkar, F.; Van der Linden, D.; Valois, S.; Maurice, F.; Onnorouille, M.; Lapointe, N.; Soudeyns, H.; Lamarre, V. Health outcomes and the transition experience of HIV-infected adolescents after transfer to adult care in Québec, Canada. BMC Pediatr. 2016, 16, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, M.; Carlqvist, A.; Cluver, L. Recent Interventions to Improve Retention in HIV Care and Adherence to Antiretroviral Treatment among Adolescents and Youth: A Systematic Review. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2019, 33, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, L.A.; Tuchman, L.K.; Hobbie, W.L.; Ginsberg, J.P. A social-ecological model of readiness for transition to adult-oriented care for adolescents and young adults with chronic health conditions. Child Care Health Dev. 2011, 37, 883–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taukeni, S.G. Biopsychosocial Model of Health. Psychol. Psychiatry Open Access 2020, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Okonji, E.F.; Van Wyk, B.; Mukumbang, F.C. Applying the biopsychosocial model to unpack a psychosocial support intervention designed to improve antiretroviral treatment outcomes for adolescents in South Africa. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2022, 41, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, G.; Mburu, G.; Tuot, S.; Khol, V.; Ngin, C.; Chhoun, P.; Yi, S. Social-support needs among adolescents living with HIV in transition from pediatric to adult care in Cambodia: Findings from a cross-sectional study. AIDS Res. Ther. 2018, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rungmaitree, S.; Thamniamdee, N.; Sachdev, S.; Phongsamart, W.; Lapphra, K.; Wittawatmongkol, O.; Maleesatharn, A.; Khumcha, B.; Hoffman, R.M.; Chokephaibulkit, K. The Outcomes of Transition from Pediatrics to Adult Care among Adolescents and Young Adults with HIV at a Tertiary Care Center in Bangkok. J. Int. Assoc. Provid. AIDS Care 2022, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegede, O.E.; van Wyk, B. Transition Interventions for Adolescents on Antiretroviral Therapy on Transfer from Pediatric to Adult Healthcare: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Question: What Are ALHIVs’ Experiences with Practices Facilitating Their Transition from Pediatric to Adult ART in Low and Middle-Income Countries? [31] | |

|---|---|

| S Sample | Adolescents living with HIV on ART |

| PI Phenomenon of Interest | Practices on transitioning from pediatric to adult care |

| D Design | All forms of qualitative and mixed-method designs, which include qualitative data collection, such as interviews, focus groups, and observations. |

| E Evaluation | Experiences, engagement in care, adherence, mental wellness, motivation, self-efficacy |

| R Research Type | Qualitative and mixed methods |

| Themes | Sub-Themes | Code | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-transition | Transition readiness | Felt ready to transition | Participants felt they had the necessary skills to transfer to adult care. |

| Informed about the transition | Participants were given sufficient information on what the transition is, what it entails, and what will follow after they transition. | ||

| Not prepared | Participants were not prepared for the transition, not knowing what will happen in the adult clinic. | ||

| Self-efficacy | Participants demonstrated a responsibility over the management of their illness prior to transitioning and took an active role in ensuring their health is optimal. | ||

| Transition | Structural barriers | Difficulty accessing clinic visits | Going to the adult clinic would mean that the participants would have to miss school or work, or they would have to miss their appointments to go to school or work. They would also have to go alone, which makes it difficult to attend, and the waiting hours are longer. |

| Financial constraints | Participants could not afford services in adult clinics, whereas the pediatric/youth services were free. | ||

| Treatment literacy | Knowledge about treatment | Participants spoke about what they knew about their medication and that they must remain adherent to stay healthy. They also voiced concerns that the adult clinic might not provide them with education and support as the youth/pediatric services did. | |

| Full disclosure | Participants were not fully informed about their HIV status and the need for treatment until they were told to move to the adult clinic. | ||

| Uninformed about the transition | Participants were told to move to the adult clinic without being explained what the transfer entails by healthcare workers (HCWs), as well as a lack of information on their overall well-being. | ||

| Post-transition | Positive adjustment to adult care | Positive experiences of the transition | Participants experienced the transition as positive, having no challenges after transitioning and finding the adult clinics more sufficient and independent. |

| Recommendations to improve the transition process/experience | Participants gave possible recommendations that would make the transition easier for them, such as collaboration between HCWs and caregivers and pediatric HCWs and adult HCWs, as well as more adolescent-friendly services. | ||

| Individual barriers | Emotional responses to the healthcare transition | Isolation | Participants felt isolated at the adult clinics, that they could not talk to anyone (staff and other patients), but also that they could not tell anyone in their personal lives about their illness. |

| Negative feelings about the change to adult services | Participants did not want to move to adult services, fearing they will not obtain the same care as in pediatric services, that it takes longer, and that they have no privacy. | ||

| Psychological impact of living with HIV | Negative feelings about illness | Participants expressed feeling bad about having HIV. | |

| Stigma | Participants expressed fears of being stigmatized by people at the adult clinics as well as in their personal lives. | ||

| Supportive environment | Psychosocial support | Caregiver involvement | Parents/caregivers should be more involved and knowledgeable about their care |

| Familial support | Participants expressed how their family members ensured that they took care of themselves, helped them remain adherent, and came to their clinic appointments. | ||

| Peer support | Support the participants experienced from their friends who knew about their HIV status. | ||

| Clinical support | Lack of healthcare worker support at adult services | In the pediatric services, participants felt like the doctors and nurses were their “friends”. Participants in the adult clinic felt like the HCWs did not give them the same type of care and support. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Petinger, C.; Crowley, T.; van Wyk, B. Experiences of Adolescents Living with HIV on Transitioning from Pediatric to Adult HIV Care in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Adolescents 2025, 5, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5020021

Petinger C, Crowley T, van Wyk B. Experiences of Adolescents Living with HIV on Transitioning from Pediatric to Adult HIV Care in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Adolescents. 2025; 5(2):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5020021

Chicago/Turabian StylePetinger, Charné, Talitha Crowley, and Brian van Wyk. 2025. "Experiences of Adolescents Living with HIV on Transitioning from Pediatric to Adult HIV Care in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis" Adolescents 5, no. 2: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5020021

APA StylePetinger, C., Crowley, T., & van Wyk, B. (2025). Experiences of Adolescents Living with HIV on Transitioning from Pediatric to Adult HIV Care in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Adolescents, 5(2), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/adolescents5020021