Abstract

Social changes have significantly impacted the educational system at various levels, for example, through legislative reforms, and have consequently guided the teaching–learning process. One of the emerging methodologies is Service-Learning (SL), which directly affects student competence and promotes habits related to physical activity and health. The present quasi-experimental study examined the impact of an SL program on secondary school students (n = 112). The aim of the 16-session SL program, which was part of the Physical Education course, was to improve the physical condition and health of 18 sedentary older adults. The influence of this program on motivation, the prosocial climate, and the importance that the students attribute to the subject of Physical Education was assessed. The most significant results were found to be those related to the School Prosocial Climate linked to empathy (p < 0.05) and the motivational variable of Intrinsic Motivation for Stimulating Experiences (p < 0.01). In conclusion, it was determined that the implementation of a methodology based on SL has positive effects on students’ empathy and intrinsic motivation.

1. Introduction

Profound socioeconomic, technological, and cultural changes, especially in the last decade [1], have greatly influenced the teaching–learning (T-L) process, affecting the way students acquire knowledge and, consequently, the way teachers must deliver their instruction [2]. To adapt to these changes, it is essential to employ active methodologies that place students at the center of learning, giving them prominence that traditional methodologies do not [3]. Additionally, active methodologies that facilitate student experiences in a real context led to a profound restructuring of the T-L process [4]. This has an impact on didactic aspects, affecting fundamental elements such as the teacher–student relationship and the evaluation of both students and the process, and highlights the need for formative, educational, and integrative evaluation [5].

This is not a passing trend but a requirement at different levels supported by significant curricular changes introduced since the enactment of the Organic Law of Education 2/2006 [6] and its renowned “Competency-Based Teaching”, which has led to the consolidation of the Pedagogical Models described by Metzler [7]. This has shaped a pedagogical proposal with a theoretical basis and empirical foundation that demonstrates its value [8], giving rise to an emerging methodological direction, from which approaches such as the Sports Education Model, the Personal and Social Responsibility Model, and Service-Learning (SL), have originated [9].

Currently, Service-Learning (SL) plays a prominent role in current legislation as one of the didactic methodologies to consider when developing specific competencies related to sustainability, ecology, and community service [10]. It is explicitly stated that it serves “to promote the integration of the competencies worked on, […] to carrying out significant and relevant projects and to the collaborative resolution of problems, reinforcing self-esteem, autonomy, reflection, and responsibility” [10]. This excerpt largely justifies the intervention proposed in the present research as key competencies are integrated through a Service-Learning (SL) project, making it relevant, significant, and therefore capable of improving aspects related to self-esteem, entrepreneurship, and critical thinking [11].

Service-Learning (SL) is an experiential and dialogical methodology based on projects that emphasize a competency-based approach. It is defined as a methodological strategy that provides a service that benefits the community where the students reside, in which the participating agents are trained by engaging with the real needs of the environment with the aim of improving it [12].

As previous studies point out [13,14], this methodology directly impacts the level of competence acquired by students, especially in terms of entrepreneurship, civic–social competence, and social justice [15], as well as the levels of motivation toward the developed physical sports programs [16].

While most publications on Service-Learning (SL) and Physical Education (PE) are at the university level [11], there are also numerous studies showing how this pedagogical model can be a key element for the T-L process in school PE. These studies demonstrate SL’s role in enhancing key aspects such as the development of prosocial elements and positive attitudes toward various groups, including immigrants [17]; fostering the development of a more effective personality [18]; and addressing fundamental aspects during a crucial period in terms of students’ self-esteem. It is observed that many of the undertaken programs are directed toward raising awareness among involved students regarding socially disadvantaged groups, using physical activity and sports (PAS) as a socializing and inclusive tool [19].

SL has demonstrated multiple benefits in socially significant aspects such as teamwork, empathy, and critical thinking [20]. These benefits not only affect the students participating in these experiences but also the target group of the SL program, with positive effects on personal initiative skills [21] and leadership in intergenerational proposals [18]. SL practices involving older adults promote a valuable intergenerational exchange, where knowledge, skills, and experiences are shared between different generations. One of the most prominent effects of these types of SL projects is the development of empathy in students. By interacting with older adults, students learn to understand and appreciate the life experiences of this group, which fosters greater sensitivity to their needs and challenges. This mutual understanding is essential for building a more inclusive society [18,22].

As Corral-Robles et al. [23] state, SL projects should always be linked to the curriculum of the subject where they are developed. This provides an excellent opportunity to develop both the basic knowledge and the specific competencies of the area through comprehensive theoretical–practical training. In this way, key competencies such as civic competence or entrepreneurship are enhanced, with the number of hours dedicated to the program and its application being crucial to amplifying its effects [13].

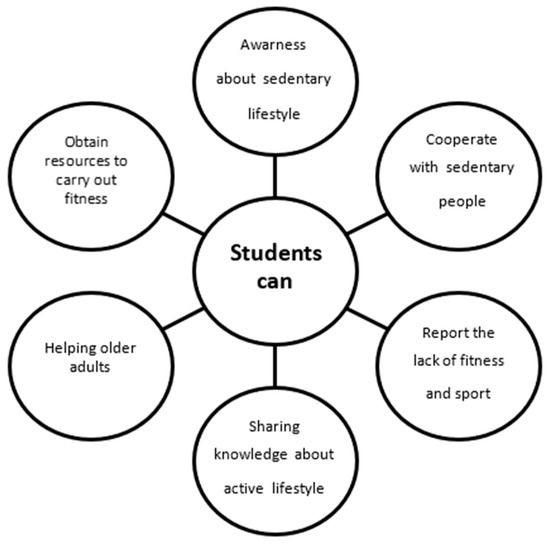

These types of projects can be extremely useful for promoting the health of the recipients [24], i.e., older adult family members in this intervention, despite adding a significant burden (Figure 1). SL is a fundamental means of promoting health at all levels, generating physical activity habits that impact overall health [3].

Figure 1.

Needs of the present SL experience, modified from Batlle & Bosch [12].

The very nature of Service-Learning (SL) justifies its incorporation into secondary education, especially in a competency-based pedagogy [25], defined as a combination of knowledge, skills, and attitudes. Knowledge consists of facts and figures, concepts, ideas, and theories that are already established and support the understanding of a specific area or topic. This includes skills, defined as the ability to perform processes and use existing knowledge to achieve results, while attitudes describe the mindset and disposition behind actions and reactions to ideas, people, or situations [26].

Thus, the aim of the present study was to analyze the impact of a 16-session SL program in Physical Education (PE) on students’ academic motivation and prosocial climate as well as to examine how methodology influences the importance they attribute to the subject.

2. Materials and Methods

The research is a quasi-experimental quantitative study with established non-random groups, conducted as a longitudinal design over a school term. The assignment of each group to either the experimental or control category was performed randomly; however, the composition of these groups was predetermined as the groups consisted of entire classes already defined at the start of the school year. Additionally, it is worth noting that the school’s criteria for forming these groups were based on the principles of diversity, ensuring that these classes shared comparable sociocultural makeup.

The collected information is related to the levels of motivation of the students, as well as their prosocial attitude and their evolution after participating in an SL program. After collecting the data, descriptive, inferential, and correlational analyses were performed based on different variables presented below.

2.1. Participants

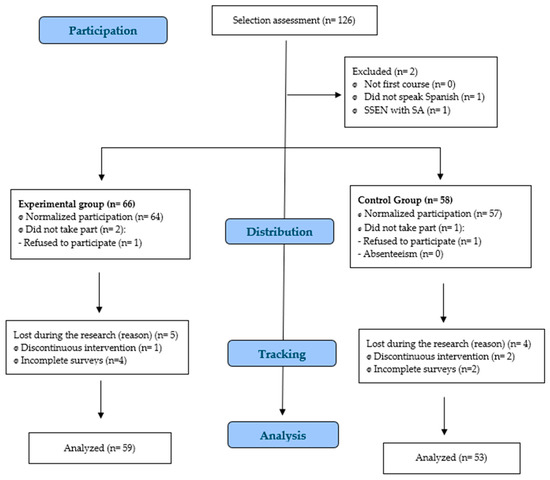

The initial sample consisted of 126 participants, with the final sample comprising a total of 112 students (control group = 53; experimental group = 59) aged between 12 and 14 years (13.08 ± 0.47). The 53 members of the control group participated in a predominantly traditional methodology based on teaching styles such as task assignment or modified direct command, although microteaching was alternately employed at certain moments of the session. On the other hand, four stages of the SL program were applied in the experimental group, with a total of 59 students, as part of a global project in which the participants had to act as health promoters through PAS (Figure 2). The classes were allocated to the control and experimental groups due to convenience and the impossibility of altering this configuration. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) not belonging to the first year of the Spanish General Certificate of Secondary Education, (ii) not speaking Spanish or having significant difficulties in its use, and (iii) special educational needs with significant adaptations in the subject involved in this study.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of participants in CONSORT. SSEN: Students with special educational needs; SA: Significant adaptation.

A description of the study participants and a comparison of the sociodemographic variables (age median, gender, practiced religion, and whether they have repeated an academic year) are shown in Table 1 for both the experiential (experimental group) and traditional (control group) SL methodologies. These participant details were obtained in the first stage of the data collection (pretest) because it was very unlikely that the sociodemographic variables of the students would change after the intervention (posttest). Therefore, the timing of data collection for participants’ sociodemographic variables was not a determining factor.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the two participating groups.

The students who formed the experimental group were organized into groups of 3–4 members, with each group member choosing a sedentary older adult who was a family member according to the following criteria: (a) man or woman over 50 years old; (b) performs less than one hour of moderate–vigorous physical activity per day [27]; (c) does not have any severe/terminal limitation or illness that prevents them from performing the proposed physical activities. The number of older adults who participated in the study was 18. Authorization to participate in the ApS programs was included in the consent the older adults had to sign for their children’s participation in the study.

Each group of participating students designed different personalized routines for their sedentary or minimally active family members, who had to carry out these routines outside of school hours for eight weeks with the students present. The students would collect evidence in video format to later show the involved teachers that the physical activities designed in class were carried out outside of it. This evidence was submitted through the Moodle platform in tasks designated for this purpose.

The study took place in a public Secondary Education Institute in the Autonomous City of Melilla. Beforehand, the parents of the participating students needed to sign an informed consent as the students were minors [28]. Subsequently, various questionnaires were completed using tablets provided by the center’s Information and Communication Technology department that collected information on the variables under study (in the Instruments Section), as well as another questionnaire to obtain demographic data of the sample.

Thus, the initial session (session 0) of the present study was used for students to complete the various questionnaires available on the Google Forms platform, where the obtained information was uploaded.

The intervention lasted 16 sessions over 10 weeks during the first term of the 2023/24 school year, specifically from 2 October to 11 December. These weeks included one weekly session in PE class for routine preparation and evaluation and another extracurricular session where the physical activity routine was practiced with one of the sedentary older family members. The objectives of the different routines are indicated in Table 2.

The basic knowledge [26] worked on was included in the didactic programming of the class group and course, thus maintaining what was established by the PE department. These contents are mainly related to promoting an active and healthy lifestyle, addressing these contents through games, directed activities, or strength and endurance tasks [9]. The experimental group approached these contents through a succession of different stages in which they configured their sessions to be carried out with the sedentary older adult based on a global project that complies with the guidelines established by Santos-Pastor et al. [29,30] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Stages of development of the SL program [29,30].

Table 2.

Stages of development of the SL program [29,30].

| Phase | SL Strategies | |

|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | Preparation |

|

| Phase 2 | Design |

|

| Phase 3 | Execution |

|

| Phase 4 | Evaluation and recognition |

|

2.2. Instruments

A series of research instruments specific to the quantitative approach were utilized, comprising mainly standardized questionnaires of a specific nature, as presented below:

School Prosocial Climate Questionnaire [34]: This questionnaire consists of the following 10 items corresponding to 10 predefined categories of prosocial behavior:

- -

- Physical Assistance: Providing support to others in achieving a specific goal.

- -

- Physical Service: Actions that eliminate the need for the recipients to physically intervene in completing a task, concluding with their approval.

- -

- Giving: The act of giving objects, food, or possessions to others.

- -

- Verbal Assistance: Providing verbal explanations or instructions or sharing ideas and life experiences that are useful and desirable for others.

- -

- Verbal Comfort: Verbal expressions with the aim of reducing sadness and boosting spirits.

- -

- Positive Confirmation and Valuation of Others: Verbal expressions that affirm the value of others or enhance their self-esteem, even in front of third parties.

- -

- Deep Listening: Meta-verbal behaviors and attentive attitudes that express patient yet active receptivity to the contents.

- -

- Empathy: Verbal behaviors that express cognitive understanding of the interlocutor’s thoughts or an emotional experience like theirs.

- -

- Solidarity: Physical or verbal behaviors that indicate a willingness to share the often painful consequences of the unfortunate conditions of others.

- -

- Positive Presence and Unity: Expressing psychological proximity, attention, deep listening, empathy, availability, assistance, and solidarity toward others.

It is answered using a Likert scale from 1 to 5 (1 = very rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = several times, 4 = often, 5 = almost always). The questionnaire was adapted for self-assessment of the frequency with which the students have experienced these behaviors, instead of co-evaluation, to facilitate data collection. This questionnaire shows high reliability values, both in the pretest phase (α = 85) and in the posttest phase (α = 0.84).

Academic Motivation Scale [35]: This questionnaire, validated and adapted for secondary school students, evaluates dimensions distributed across seven subscales, each containing 4 items, wherein students explain their reasons for attending school, totaling 28 items, as shown below ordered by the subscales. To simplify the description of the scale, an example is given for each of the subscales:

- -

- Amotivation: “I honestly don’t know, I think I’m wasting my time at school” [5].

- -

- External regulation: “Because I need at least a high school diploma/Vocational Training certificate to find a well-paying job” [1].

- -

- Introjected regulation: “To prove to myself that I am capable of finishing high school/Vocational Training” [7].

- -

- Regulation identified: “Because it will help me make a better decision regarding my career orientation” [17].

- -

- Intrinsic motivation for knowledge: “Because I feel pleasure and satisfaction when I learn new things” [2].

- -

- Intrinsic motivation for achievement: “For the pleasure I feel when I excel in my studies” [6].

- -

- Intrinsic motivation for stimulating experiences: “Because I genuinely enjoy attending classes” [4].

Responses are rated on a seven-point Likert scale, where 1 indicates “strongly disagree”, 2 indicates “disagree”, 3 is “partially disagree”, 4 is the midpoint indicating moderate correspondence with “neither agree nor disagree”, 5 is “partially agree”, answer 6 indicates “agree”, and 7 indicates complete correspondence with “strongly agree”. This scale shows satisfactory internal consistency, with an average Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.80 and high temporal stability indices, with an average test–retest correlation of 0.75.

Questionnaire on the Importance of PE [36]: This questionnaire consists of three items designed to measure adolescents’ perception of the relevance and usefulness of PE classes. The items are as follows:

- I consider it important to receive PE classes.

- Compared to other subjects, I think PE is one of the most important.

- I think the things I learn in PE will be useful in my life.

Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale, from 1 “Totally disagree” to 4 “Strongly agree” along with the middle options 2 “Quite disagree” and 3 “Quite agree”. Factor analysis of these items shows solid internal consistency, with values of 0.827, 0.814, and 0.818 for items 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Additionally, principal component factor analysis with varimax rotation gives a value of 2.01 for the grouping of factors related to the importance of PE, explaining 67.15% of the total variance. The reliability coefficient is 0.75, indicating a high correlation.

2.3. Procedure

This study has the approval of the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Granada (No. 3636/CEIH/2023) as part of the research “Influence of Dialogic Programs on Motivation, Prosocial Climate, and Importance of the PE subject in Secondary Education students”. Additionally, since the intervention took place in the educational field, approval for its implementation was obtained from the Ministry of Education and Vocational Training (MEFP).

The teaching staff at the study location approved the application of the questionnaires and the intervention with the participating students. Prior permission had been obtained from the management team to conduct the research, from the adults and students, and from the parents of participating minors. The students completed the questionnaires individually using tablets provided by the center through the Information and Communication Technology department. These questionnaires were completed entirely anonymously, and completion was monitored using an identification code provided by the teachers, both in the pretest (7–10 days before the start of the SL intervention) and in the posttest (7–10 days after the end of the SL intervention). These steps were carried out during the PE class during a playful session where the students attended in groups of eight to complete the questionnaires, which took them about 15 min to complete. This process was controlled by the teachers in charge of the research, and student/teacher roles were established to maintain control over the class when physical sports activities were carried out. The teachers themselves indicated to the students that their participation was voluntary and would not count toward the subject’s evaluation. No problems were encountered when the students completed the questionnaires.

Table 3 lists the different sessions (S) developed as well as the strategies developed within the proposed SL program corresponding to the three units (Us) called “Personal Trainers” (U2), where the project is presented and the starting point is established, “Get in shape!” (U3); where strength is preferably worked on; and “Healthy Sauté” (U4), where students develop different aspects of cardiorespiratory capacity through rhythmic systems, jump rope routines, and body expression.

Table 3.

Sessions, contents, and strategies developed in the SL program.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Initially, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to test for data normality, and it was found that the study variables follow a normal distribution. The mean, standard deviation, and the numbers and percentages of the variables evaluated in the three tables shown in the next section were calculated.

Student’s t-test was used to determine the differences between the experimental and control groups regarding sociodemographic variables. The magnitude of the differences between the evaluations (pretest and posttest in the same group; experimental and control) was measured with Cohen’s d test for effect size [37], interpreted as small (0.2 < d < 0.5), medium (0.5 < d < 0.8), or large (0.8 < d).

The pretest and posttest data of both groups were compared for the variables: importance of PE, Academic Motivation Scale, and School Prosocial Climate. Additionally, a stepwise multiple regression analysis was performed on the posttest evaluation to evaluate the possible association between the mentioned variables. According to Field [38], the ranges of values used to interpret the strength of relationships in a linear regression analysis (coefficient of determination; R2) are weak (0.01 < R2 < 0.09), moderate (0.09 < R2 < 0.25), or strong (R2 > 0.25).

The order of variables entered in the different steps was based on the study objectives and on previous findings regarding the association between the three items of the questionnaire of the importance of PE, School Prosocial Climate, and the Academic Motivation Scale in secondary school students [39].

The statistical analyses in the present investigation were carried out with the IBM SPSS Statistics v.25 software package.

3. Results

Regarding the results obtained after the SL intervention in terms of the importance of PE, Academic Motivation Scale, and School Prosocial Climate (Table 4), the usefulness of the PE content learned in class was evident only in the group that followed a traditional methodology (control group) (p < 0.05), specifically in relation to item 3 “I believe that the things I learn in PE will be useful in my life.”

Table 4.

Differences in the questionnaire items on the importance of PE, School Prosocial Climate, and dimensions of the Academic Motivation Scale between the two participating groups.

However, the results for the experimental group, which developed an experiential SL intervention, showed significance both in terms of School Prosocial Climate related to empathy (p < 0.05) and the motivational variable of Intrinsic Motivation for Stimulating Experiences (p < 0.01). However, to mitigate type 1 error in the analyses shown in Table 4, the significance level was adjusted from p < 0.05 to p < 0.01. Consequently, IM-to stimulation was considered a significant variable along with its corresponding effect size.

Table 5 shows the independent associations of the three items from the questionnaire on the importance of PE with the dimensions of the School Prosocial Climate and the Academic Motivation Scale for both participating groups in the posttest evaluation.

Table 5.

Stepwise multiple regression analysis of the items of the questionnaire on the importance of PE, School Prosocial Climate, and the dimensions of the Academic Motivation Scale for both participating groups in the posttest evaluation.

According to item 1 regarding the importance of PE, verbal help was introduced in step 1 (R2: 8.4% of the variability, p: 0.026) for the group participating in the experimental methodology, and the strength of the relationships was weak. Items 2 and 3 showed non-significant independent associations with the remaining dimensions of School Prosocial Climate and the Academic Motivation Scale.

On the other hand, physical service was introduced in step 1 (R2: 14.5% of the variability, p: 0.005) and step 3 (R2: 12.8% of the variability, p: 0.009) for the group participating in the traditional methodology, showing a moderate relationship between variables. Item 2 showed non-significant independent associations with the remaining dimensions of School Prosocial Climate and the Academic Motivation Scale.

4. Discussion

The effects of a 16-session SL program in the PE area were analyzed in the present study. The impact of the program on academic motivation as well as on the prosocial climate of the school and the effects this methodology may have on the importance students attribute to the subject itself were evaluated. To achieve this, a quasi-experimental design was employed alongside a methodology using mainly traditional and participatory teaching styles to determine the level of changes that occurred once the program had been completed.

Previous studies related to SL have shown positive effects on the variables studied in this intervention, such as motivation [40] and prosociality [14]. Regarding the importance of PE, no previous studies related to this pedagogical model have been found.

Concerning prosociality, our study shows that the implementation of an SL experience fosters empathy in students, as improvement, determined by the effect size (0.419), was observed in how students rejoice in the happiness of others, a fundamental element within prosociality. Authors such as Batlle and Bosch [12] point out that this is an inseparable aspect of this methodology and leads to the generation of fraternal bonds. The results obtained in the present study are complemented by the experience described by Sánchez et al. [41], where improvements in prosocial aspects such as empathy and solidarity were also demonstrated. The improvement in these values is considered fundamental within the educational process, constituting one of the main challenges for the educational system [42].

As highlighted by García-Taibo et al. [43], SL can transform the involved students through the acquisition of prosocial behaviors in socially disadvantaged contexts and groups, promoting key competencies such as citizenship through the improvement of social sensitivity and awareness, the promotion of social justice, as well as the emerging construction of intercultural citizenship. This is of great relevance to our study, conducted in a fully intercultural context in the Autonomous City of Melilla, with the sample students being of Berber, Jewish, Christian, and non-religious descent. These students worked in groups through the different SL stages, cooperating to achieve the set objectives. One of the study’s limitations is the control of this intercultural variable in the sample and its relationship with the results. As described by Lamoneda et al. [17], improvements in prosocial attitudes and contributions to value education, as well as improved coexistence through the SL methodology in ES, are evident, in this case through the application of said program in adult–elderly groups [44].

Regarding motivation, the implementation of an SL program makes student learning a stimulating experience. This aspect has been widely referenced in the recent literature [45,46], being one of the elements most related to the implementation of SL. This increase in motivation, demonstrated by the results in relation to the p-value (0.07) as well as the effect size (0.430), toward experiences that stimulate students is determined by various important aspects of this methodology, such as teamwork [29] as well as the application of the learned content both outside and inside the school environment and the consequent benefit for the environment [40]. Additionally, both the acquired competence development and the attitudinal component in the SL sessions of this study, where students worked on physical condition and health to combat sedentary habits in the adult elderly group, are characteristics of SL programs with primary (EP) [18] or secondary [17] education students working with various groups or causes.

Another aspect to consider is the one evaluated in a study by Valero-Valenzuela et al. [47], which links teaching performance with intrinsic motivation and the adoption of an active lifestyle in Spanish students. Promoting student autonomy is essential to achieving the highest levels of motivation and participation during the teaching process, and this can be achieved by adopting active methodologies such as SL, where student emancipation is evident [48]. Thus, the role of teachers in the classroom is relevant through the support of autonomy, contributing to achieving higher levels of motivation toward stimulating experiences and a more active lifestyle. Additionally, the SL methodology promotes teamwork, fostering skills that enable effective communication in line with the aims of dialogic learning [24].

Another element to highlight is how SL promotes the performance of AFD linked to health, closely related to the importance that students attribute to the PE subject as a promoter of healthy habits [49]. In the present study, the influence of PE was expanded beyond the school environment in such a way that the proposals linked to SL programs, whereby the promotion of a healthy lifestyle was carried out by training sedentary elderly family members, proved to be an excellent promoter of healthy values, commitment, social involvement, and empathy toward others, both in the involved students and their families [9,50]. This fact indicates the social transformation capacity that the implemented methodology has with respect to the promotion of healthy habits and prosocial attitudes, as shown by the study conducted by Founaud-Cabeza and Santolaya-Del Val [51], in which there was an increase in the use of bicycles and, therefore, active transportation, in a school. Another example is the study by Ruiz-Montero et al. [18], showing that primary education students acquired a more critical and empathetic attitude toward others during an SL intervention with dependent elderly groups as part of the PE subject. Likewise, it was the adoption of these contents (basic knowledge) linked to health and physical activity, as well as respect for oneself and others, that produced significant results in the control group. This was specifically evident for the item “I believe that the things I learn in PE will be useful in my life”, since the traditional methodology focuses more on training methods to improve the physical condition of the students themselves and less on the application of this knowledge to other groups of people.

Regarding the regression analysis with the different variables of the study shown in Table 5, a significant relationship was observed in the experimental group between item 1 of the importance of the PE questionnaire and dimension 4 of the prosocial climate questionnaire (verbal help). This suggests that students who participated in experimental methodology consider it important to participate in PE classes and have better prosocial behavior, as indicated in their provision of verbal help to their peers. The model explained 8.4% of the variability in school prosocial climate, indicating a weak relationship. These findings are in line with previous studies, such as the study conducted by Rojo-Ramos et al. [52] who reported a positive relationship between the importance of PE and improved verbal communication elements. Additionally, the practice of physical sports activities improves prosocial behavior, being a fundamental avenue for the inclusion of students with special educational needs [53].

In the case of the control group, a moderate effect size was identified for item 3 of the PE importance questionnaire—“I think the things I learn in PE will be useful in my life”—suggesting that the application of a traditional methodology can positively influence the importance that students attribute to receiving PE classes as well as providing physical help to their peers. This relationship is justified by the moderate connection with engaging in physical activity that focuses on improving physical fitness and performance, which is typical of traditional PE teaching, suggesting it can increase the perceived importance of peers’ physical support [54].

It is important to note that different SL programs that were linked to basic physical capacities and oriented toward health promotion were implemented in the first trimester of the 2023/24 school year. This fact is relevant since the program investigated in this study was a first-year ESO course newly integrated into a secondary school, with significant changes occurring in the composition of the groups as well as in the assimilation of changes at different levels by the students [55]. Therefore, the unit prior to this study focused on group cohesion through the implementation of cooperative games and tasks, using Cooperative Learning [56] to promote the inclusion of these students, an aspect that might have influenced the current study, especially concerning the prosocial variable. However, this methodology was only developed over five sessions, which was insufficient to provoke significant effects.

This study demonstrated a positive relationship between the implementation of an SL program and student prosociality and motivation. Empathy, which involves the ability to understand and share the feelings of others, is one of the values that most effectively strengthens a prosocial classroom climate [57]. Furthermore, educational experts highlight the importance of fostering intrinsic motivation, which is critical for encouraging autonomous and experimental learning [58].

As suggested by various authors [29], there is a lack of evaluation of the effects of SL, a scarcity of instruments and procedures to evaluate these effects both in students and the recipient groups, and an absence of diversity among existing SL programs.

One of the main limitations of the study is the lack of control over the participants’ activity outside the curricular schedule and the promotion of AFD outside the school environment, which complies with the forty-sixth additional provision of the Organic Low of Education (OLE): “Promotion of physical activity and healthy eating” [6], complemented by the modification of OLE [10]. Despite evidence of the completion of the different proposed tasks, the dedication of each participant was not exactly quantified. Another limitation is the duration of the SL experience. The program barely reached 8 weeks, which is a timeframe shorter than others carried out with this methodology. However, it can still be considered to be within a suitable intervention range [19].

Fernández-Bustos conducted a study that hybridizes SL with the pedagogical model of Sports Education, showing that the combination of both methodologies creates an ecosystem that fosters the development of socioemotional aspects linked to the learning of the sport itself and offers positive experiences for all participants, including those who provided the service to the community [59]. Therefore, future lines of research should consider this aspect and determine which elements of each methodology promote comprehensive student learning. In this way, we can employ and implement strategies from various pedagogical models in the daily development of classes. This allows us to readily adapt a methodology such as SL to other experiences based on models like the Personal and Social Responsibility Model or Sports Education. This adaptation is achieved through elements transferable between these methodological approaches, such as group organization, effective communication, role adoption, and the promotion of progressive autonomy—features that are inherent to active methodologies focusing on students.

5. Conclusions

The main results obtained in this study support the relationship between SL and key variables in the T-L process, such as motivation and a prosocial climate. The importance of this model becomes even greater given that, according to the best of our knowledge and the prior literature review, there are few references to this type of pedagogical experience in secondary education. Therefore, we believe it is essential to consider not only the findings at the results level but also the methodological and pedagogical elements that should be described clearly and concisely, with the aim of encouraging new experiences in this educational field, which, as previously mentioned, offer significant benefits for students.

Furthermore, it is important to highlight that this study was conducted with students in a highly vulnerable stage, transitioning from primary to secondary education in the Spanish system. Facilitating this transition through stimulating experiences is fundamental, as observed in the implementation of SL programs. While motivation can be an advantage, excessive motivation can lead to disruptive behaviors, which are already frequent during this educational period. We must therefore emphasize the capacity of this type of pedagogical initiative to enhance empathy, one of the most relevant prosocial elements.

The results obtained should be interpreted with caution due to the various limitations outlined above. This study is cross-sectional, meaning that causal relationships cannot be categorically established to affirm that the differences observed are solely due to the implementation of the SL program; they may also be influenced by the contextual and cultural profile of the participants. Thus, future research is warranted to confirm and strengthen the presented results. Finally, it is worth noting that this study can be highly useful in guiding secondary education teachers on how to implement this active methodology in their classes, not only in PE but also in any other subject, as the method is entirely transferable to other disciplines. It provides real-world experiences aimed at improving students’ surroundings, reinforcing a key aspect of the current educational system—meaningful learning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H.-G. and P.J.R.-M.; formal analysis, P.J.R.-M.; investigation, A.H.-G.; data curation, A.H.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H.-G., E.-M.H. and M.L.S.-P.; writing—review and editing, A.H.-G., M.L.S.-P. and P.J.R.-M.; visualization, P.J.R.-M.; supervision, P.J.R.-M.; project administration, A.H.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Granada (No. 3636/CEIH/2023) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants and their parents (in the case of minors) involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets of this study are available at 10.6084/m9.figshare.28414793.

Acknowledgments

Our sincere thanks to all the participants and their families. This research is part of the first author’s doctoral thesis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hernández Navarro, H.; Barboza Hernández, J.L.; Gándara Molino, M.; Hernández Flórez, N. Environmental Sustainability and the Challenges in Education in the 21st Century: A Systematic Review of the Literature. In Research Practices of Young Researchers in Sucre; Álvarez, L., Hernández, M., Baldovino, K., Eds.; Editorial CECAR: Sincelejo, Colombia, 2023; Volume 2, pp. 7–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintado-Crespo, M.L.; Guaña-Moya, E.J.; Flores-Cabrera, P.A.; Cadme-Galabay, T.A.; Cadme-Galabay, M.R. Virtual Learning Environments and Social Networks as Tools in Intensive Education. Polo Del Conoc. 2022, 7, 1524–1535. [Google Scholar]

- León-Díaz, Ó.; Arija-Mediavilla, A.; Martínez-Muñoz, L.F.; Santos-Pastor, M.L. Active methodologies in Physical Education. An approach of the current state from the perception of teachers in Madrid Community. Retos 2020, 38, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beneyto-Seoane, M.; Simó-Gil, N. Current Educational Practices of Pedagogical Renewal: A Critical Perspective. REICE Rev. Iberoam. Sobre Calid. Efic. Cambio Educ. 2023, 21, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Pueyo, Á.; Hortigüela Alcalá, D.; González Calvo, G.; Fernández Río, J. Formative and shared assessment in physical education: Foundations and practical experiences at all educational stages. Publ. Univ. León 2024, 49, 183–198. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10612/22962 (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Government of Spain. Organic Law on Education. 2/2006 3 May 2006, p. 106. Official State Gazette. Available online: https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2006/05/04/pdfs/A17158-17207.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Pill, S.; SueSee, B.; Davies, M. The Spectrum of Teaching Styles and models-based practice for physical education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2024, 30, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Tejerina, D.; Fernández-Río, J. Health-based physical education model. A systematic review according to PRISMA guidelines. Retos 2023, 51, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Pueyo, Á.; Hortigüela Alcalá, D.; González Calvo, G.; Fernández Río, J. Move with me, a Service-Learning project in the context of physical education, physical activity and sport. Publicaciones 2019, 49, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Spain. Organic Law 3/2020 amending Organic Law 2/2006 on Education. Section 340 of the Official State Gazette. 9 December 2020. Available online: https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2020/12/30/pdfs/BOE-A-2020-17264.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Chiva, Ò.; Gil, J.; Corbatón, R.; Capella, C. Service learning as a methodological approach for the critical pedagogy. RIDAS Rev. Iberoam. Aprendiz. Serv. 2016, 2, 70–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batlle, R.; Bosch, C. Aprendizaje-Servicio: Compromiso Social en Acción; Santillana Educación: Tres Cantos, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Capella-Peris, C.; Gil-Gómez, J.; Chiva-Bartoll, Ò. Innovative Analysis of Service-Learning Effects in Physical Education: A Mixed-Methods Approach. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2020, 39, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Montero, P.J.; Santos-Pastor, M.L.; Martínez-Muñoz, F.; Chiva-Bartoll, O. Influence of the university service-learning on professional skill of students from physical activity and sport degree. EducXX1 2022, 25, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Gómez, T. Proposal for Initial Teacher Training for Democracy and Social Justice According to the Service-Learning. Int. J. Sociol. Educ. 2022, 11, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echauri-Galván, B. Learning at the service of motivation: The impact of sl on students’ motivation in a translation module. Contextos Educ. 2023, 31, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamoneda Prieto, J.; Carter-Thuillier, B.; López-Pastor, V.M. Effects of a learning and service program on the development of prosociality and positive attitudes toward immigration in physical education. Publicaciones 2019, 49, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Montero, E.; Sánchez-Trigo, H.; Batista, P.; Ruiz-Montero, P.J. Participation in an intergenerational service-learning experience and prosocial behaviour: The importance of physical education and its mediating role. RICCAFD 2024, 13, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ordás, R.; Nuviala, A.; Grao-Cruces, A.; Fernández-Martínez, A. Implementing Service-Learning Programs in Physical Education; Teacher Education as Teaching and Learning Models for All the Agents Involved: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco Cano, E.; García-Martín, J. The impact of service-learning (SL) on various psychoeducational variables of university students: Civic attitudes, critical thinking, group work skills, empathy and self-concept. A systematic review. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2021, 32, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- June, A.; Andreoletti, C. Participation in intergenerational Service-Learning benefits older adults: A brief report. Gerontol. Geriatr. Educ. 2020, 41, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualano, M.R.; Voglino, G.; Bert, F.; Thomas, R.; Camussi, E.; Siliquini, R. The impact of intergenerational programs on children and older adults: A review. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2018, 30, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral-Robles, S.; Hooli, E.M.; Ortega-Martín, J.L.; Ruiz-Montero, P.J. Competences and Physical Activity -based Service-Learning of future Primary School English teachers. Retos 2022, 45, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Montero, P.J.; Chiva-Bartoll, O.; Salvador-García, C.; González-García, C. Learning with Older Adults through Intergenerational Service Learning in Physical Education Teacher Education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brozmanová-Gregorová, A.; Heinzová, Z.; Kurčikov, K.; Nemcová, L.; Šolcová, J. Development of key competences through service-learning. Rev. UNES Univ. Esc. Y Soc. 2019, 6, 34–54. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10481/58881 (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Government of Spain. Order EFP/754/2022, of July 28, establishing the curriculum and regulating the organization of Compulsory Secondary Education within the scope of the Ministry of Education and Vocational Training. EFP/754/2022. Official State Gazette, Section 187. 28 July 2022. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2022-13172 (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- WHO. Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour: At a glance. Ginebra, Suiza: Organización Mundial de la Salud (WHO). 2020. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/337004/9789240014817-spa.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Baeza, C. The ethical dimension of educational research. Revista Ethika+ 2020, 1, 46–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Pastor, M.L.; Martínez-Muñoz, L.F.; Ruiz-Montero, P.J.; Chiva Bartoll, O. Guía Práctica Para Proyectos de Aprendizaje-Servicio en Educación Física. Ministerio de Cultura. 2024. Available online: https://digibug.ugr.es/handle/10481/87083. (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Santos-Pastor, M.L.; Ruiz-Montero, P.J.; Chiva-Bartoll, O.; Martínez-Nuñoz, L.F. Guía Práctica Para el Diseño de Programas de Aprendizaje-Servicio en Actividad Física y Deporte. Junta de Andalucía. 2021. Available online: https://digibug.ugr.es/bitstream/handle/10481/70964/Gu%c3%ada%20ApS_AFD.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Canillas-Molina, A.; González-Fernández, F.T.; Martín-Moya, R.; Ruiz-Montero, P.J. Motivational effect of an Escape Room and a Service-Learning program for the content of “Physical condition assessment in older-adults” in students of Primary Education and Physical Activity and Sports Sciences Bachelor’s Degree of Melilla. Estud. Pedagógicos. 2021, 47, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Gómez, E.; Sánchez-Ojeda, M.A.; Martín-Salvador, A.; Enrique Mirón, C. Relationship of the influence of physical activity with cardiovascular risk factors in adult citizens of Melilla. Sport TK 2020, 9, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription; Wolters Kluwer: Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Romersi, S.; Martínez-Fernández, R.; Roche, R. Efectos del Programa Mínimo de Incremento Prosocial en una Muestra de Estudiantes de Educación Secundaria. An. De Psicología 2011, 27, 135–146. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10201/26449 (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Núñez, J.L.; Martín-Albo, J.; Navarro, J.G.; Suárez, Z. Adaptation and validation of the Spanishversion of the Academic Motivation Scale in post-compulsory secondary education students. Stud. Psychol. 2010, 31, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Murcia, J.; Coll, D.; Ruiz Pérez, L. Self-Determined Motivation and Physical Education Importance. Hum. Mov. 2009, 10, 5–11. Available online: http://www.degruyter.com/view/j/humo.2009.10.issue-1/v10038-008-0022-7/v10038-008-0022-7.xml (accessed on 8 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS: Introducing Statistical Method, 6th ed.; University of Sussex, Sage Publications: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyo-Guillot, A.; Ruiz-Montero, P.J. Influence of a personal and social responsibility model intervention on educative motivation, prosocial environment and Physical Education importance on secondary school students. ESPIRAL 2023, 16, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador Ferrer, C.M.; Andrés Romero, M.P.; Fernández Torres, M.; Salguero García, D. Competencies, motivation and engagement of university students through service-learning experiences. ESPIRAL 2023, 16, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.; Ruescas, E.; García, B.; Portillo, L.J. A basket, a smile. Values education in non-formal education through service-learning. RIDAS 2022, 13, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade-Salazar, J.A. Educating in the planetary age, challenges of education. Entretextos 2023, 32, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Taibo, O.; Martín-López, I.M.; Baena-Morales, S.; Rodríguez-Fernández, J.E. The Impact of Service-Learning on the Prosocial and Professional Competencies in Undergraduate Physical Education Students and Its Effect on Fitness in Recipients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, J.T.; Kuo, T.; Huang, C.K.; Chang, L.H.; Hsu, Y.J.; Wang, Y.W.; Hsiao, H.-Y. Examining the Impact of the Design-Thinking Intergenerational Service-Learning Model on Older Adults’ Self-Care Behaviors and Well-Being. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2024, 44, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Empathy and prosociality: Service-learning projects in social psychology. Rev. INFAD Psicol. 2020, 2, 441–448. [CrossRef]

- Serafini, E.J. El aprendizaje-servicio en la enseñanza del español como lengua de herencia. In Aproximaciones Al Estudio Del Español Como Lengua de Herencia; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021; pp. 257–274. [Google Scholar]

- Valero-Valenzuela, A.; Merino-Barrero, J.A.; Manzano-Sánchez, D.; Belando-Pedreño, N.; Fernández-Merlos, J.D.; Moreno-Murcia, J.A. Influence of Teaching Style on Motivation and Lifestyle of Adolescents in Physical Education. Univ. Psychol. 2020, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Ardoy, D.; Collado-Martínez, J.Á.; Pellicer-Royo, I. Pedagogical Models in Physical Education, 1st ed.; Independently publisher: Chicago, IL, USA, 2020; ISBN 9798639212444. [Google Scholar]

- Santos Calero, E. Little Learners. Service-Learning Project for the Promotion of Physical Activity in Primary Physical Education. ReiDoCrea 2023, 12, 213–226. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10481/81239 (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Hernández-Rodríguez, A.I.; Lirola, M.J.; Prados-Megías, M.E. Building shared knowledge in the basic training of students. University Service Learning in Physical Recreational Activity involving people with functional diversity. Espiral Cuadernos Del Profesorado. 2024, 17, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Founaud-Cabeza, M.P.; Santolaya Del Val, M. Service-learning in physical education: Active adolescence. Aula Encuentro 2021, 23, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo-Ramos, J.; García-Guillén, M.J.; Castillo-Paredes, A.; Galán-Arroyo, C. Impact of verbal and non-verbal communication in educational settings on perception of importance of physical education in adolescence. Retos 2025, 62, 1042–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shao, W. Influence of Sports Activities on Prosocial Behavior of Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessa, C.; Hastie, P.; Ramos, A.; Mesquita, I. What Actually Differs between Traditional Teaching and Sport Education in Students’ Learning Outcomes? A Critical Systematic Review. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2021, 20, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ávila Francés, M.; Sánchez Pérez, M.C.; Bueno Baquero, A. Factors facilitating and hindering the transition from Primary to Secondary Education. Rev. Investig. Educativa 2022, 40, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís-García, P.; Gallego-Jiménez, M.G.; Real Castelao, S. Does Cooperative Learning Promote Inclusion? A Systematic Review. Páginas Edución. 2022, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Song, C.; Ma, C. Effect of Different Types of Empathy on Prosocial Behavior: Gratitude as Mediator. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 768827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, A.; Noetel, M.; Parker, P.; Ryan, R.M.; Ntoumanis, N.; Reeve, J.; Beauchamp, M.; Dicke, T.; Yeung, A.; Ahmadi, M.; et al. A classification system for teachers’ motivational behaviors recommended in self-determination theory interventions. J. Educ. Psychol. 2023, 115, 1158–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Bustos, J.G.; García López, L.M.; Gutiérrez, D.; González-Martí, I.; Abellán, J. Impact of a service-learning and sport education program on social competence and learning. EducXX1 2024, 27, 299–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).