1. Introduction

The Canary Islands consist of an archipelago of seven main islands and smaller islets in the Atlantic Ocean near the North-Western African coast. The pre-Hispanic inhabitants of the islands arrived around the 3rd century CE [

1,

2], and in 1497, the Spanish conquered the islands, giving way to an influx of Spanish colonialists to the islands. Genetic studies performed on ancient pre-Hispanic populations, on post-conquest populations of the 17th and 18th century, and on modern population groups revealed that a great proportion of pre-Hispanic genes were still present in the 17–18th century population of the Canary Islands (as well as in the contemporary one; [

3]).

On the other hand, the Spanish conquest led to very marked changes in economic activity and social structure, resulting in profound changes in the lifestyle of the conquered population.

Skeletal human variants, often called non-metric traits, are morphological features of human bone that are usually recorded as dichotomic present/absent, or following an ordinal recording method using grades of intensity. Some skeletal variations have been found to be inheritable and genetically determined [

4,

5], but others are acquired during life [

6]. Nevertheless, environmental influence can vary depending on the trait [

7]. Therefore, many postcranial traits become affected by acquired factors and can be used to examine lifestyle habits and levels of activity within a population [

8,

9,

10]. When recorded in combination, postcranial traits can be highly useful to identify relationships in cemeteries and burial grounds with documented contexts, regardless of their etiology [

11,

12,

13].

The calcaneus is very useful for osteological research in archaeological contexts due to its high bone density, which enables higher levels of preservation [

14], and also because its involvement in the standing position and walking allow the development of several traits that may provide information related to lifestyle and weight-bearing activities. The usually good preservation of the calcaneus is especially important in commingled, disturbed, and/or looted burial grounds and cemeteries where cranial non-metric trait analysis is often impossible due to damage. Additionally, well-preserved postcranial bones like the calcaneus can be used to discover relationships between skeletal individuals when the archaeological context is highly disturbed and DNA analysis is impossible due to different conditions causing contamination [

12]. These commingled conditions are common in the Canary Islands, where many pre-Hispanic cave burials are communal burial deposits, in which skeletal remains are often found disarticulated and intertwined with other individuals of previous deposits [

15,

16].

Moreover, during the three centuries after the conquest of the Islands (completed towards the end of the 15th century), and in the 18th century, Catholics had to be interred in the floor of churches, leading to space constraints, especially during fatal epidemics or famine episodes, in which several individuals were buried together or in nearby locations.

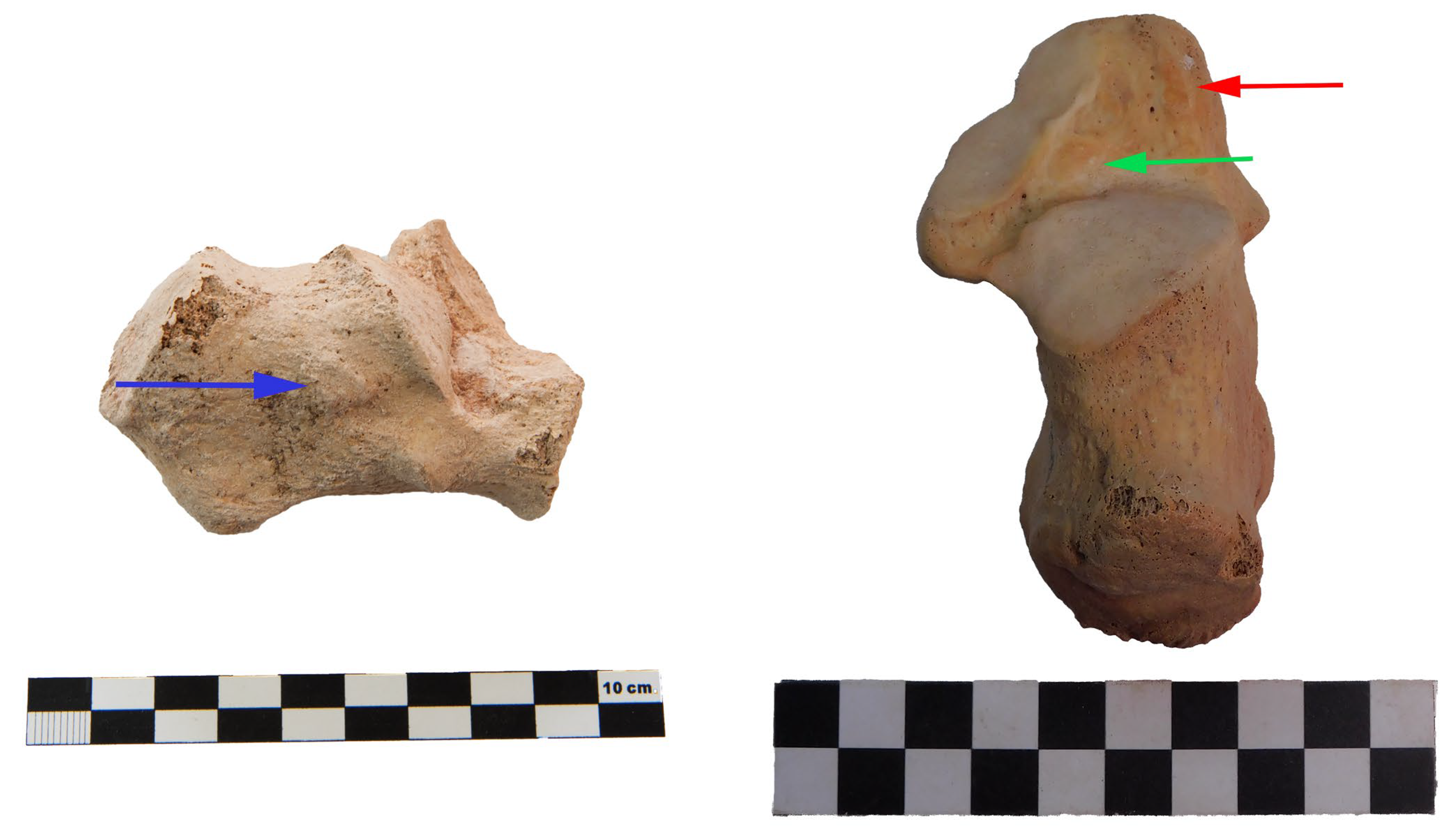

Several traits are described in the calcaneus—some of them possibly related to activity, others more dependent on genetics, although some uncertainty still exists (

Table 1). Those included in this study are the retrotrochlear eminence, Extra Facet Extension of Posterior Facet (EFEOPF), pseudo-facet, medial root of inferior

extensor retinaculum (MRIER), talo-calcaneal facets, and

calcaneus secundarius. The retrotrochlear eminence is a frequent insertion site of accessory muscles and a common insertion site for the

peroneus quartus muscle. This muscle insertion is located near to, and should not be confused with, the peroneal tubercle [

17]. The EFEOPF trait consists of a facet believed to be caused by friction from the accessory anterolateral talar facet on the talus bone due to the angle; normally, the talocalcaneal ligaments and retinaculum would prohibit friction with the talus bone during certain squatting postures, but in these cases the retinaculum and ligaments are genetically absent [

18]. The pseudo-facet is located anteriorly on the calcaneus and may appear due to a low foot arch or flat foot syndrome [

19]. The MRIER is an insertion location for the inferior

extensor retinaculum. A fibrous band attaches to the anterior–lateral part of the calcaneus, wrapping around the ankle region, and the presence of this trait may be caused by genetic–environmental factors [

20,

21]. The talo-calcaneal facets are the joints between the calcaneus and the talus bone that support the weight and movement of the ankle. These facets are considered to be genetic in origin as they can start to develop early in development, but ankle activity may also influence changes in facet morphology [

22,

23,

24,

25]. The calcaneus secundarius is an ossicle and connection site for the ossicle located on the anterior region of the calcaneus. This ossicle can be joined by cartilage with a porous texture on a semi-circular notch on the calcaneus. Type 1 calcaneus secundarius consists of a smooth semi-circular notch on the bone, while type 2 is a porous notch [

26]. For more information on these traits, we recommend consulting the atlas of non-metric traits of the calcaneus [

26].

Each trait has its significance in its inclusion in this study. All of these traits appear to have lifestyle and genetic factors influencing their presence [

26]. Regardless of whether genetics influence the appearance of these traits, lifestyle is an important factor that can differ between populations and individuals. Thus, due to their shared etiology, each trait included in this study may aid in differentiating the modern Canarian population from pre-Hispanic Canarians due to lifestyle differences.

In addition, considering that a genetic homology exists among the population living on the islands during the 18th century and the pre-Hispanic era, in the face of marked differences in economic activity, this study potentially aids in clarifying the genetic or acquired nature of some of these traits. Therefore, taking advantage of the opportunity to analyze large population groups of pre-conquest and 17th-18th century post-conquest inhabitants of the Islands, in this study we compare the prevalence of several calcaneal non-metric traits of pre-Hispanic and modern inhabitants of the islands in order to (1) test the skeletal variation between pre-Hispanic and modern (17–18th century) Canarian samples and (2) gather information on biological and lifestyle differences between the samples using the calcaneal bone.

4. Discussion

There are statistically significant differences between pre-Hispanic and modern Canarians regarding the skeletal variations in the calcanei of these samples. Variations and non-metric trait differences of the calcaneus and the ankle, in general, can likely be attributed to many factors, including a mixture of genetic and environmental influences, as seen in previous studies [

42,

43]. Furthermore, different traits of the calcaneus have differing etiologies, and previous research has shown that some traits of the calcaneus are considered more influenced by activity than others [

23,

44,

45]. However, considering the genetic homology existing among the pre-Hispanic and modern population groups, the results observed in this study generally support that the traits with significantly different proportions among the two population groups are related to differences in economic activity. In any case, each trait must be studied separately to understand the differences in proportion between the samples.

In this study, we have described the prevalence of several calcaneal traits and the typology of calcaneal facets, comparing them among two periods defined by marked differences in socioeconomic status. Although the genetic composition of the population included in each of the two groups (modern/pre-Hispanic) is not the same, the estimated indigenous genetic contribution to the 17–18th century population reaches 40%, based on Y-chromosome and mtDNA haplogroup frequencies [

3]. Despite this, some non-metric traits show striking differences among the pre-Hispanic and modern populations of the Canary Archipelago. For instance, the prevalence of EFEOPF was by far higher among the pre-Hispanic inhabitants (i.e., regarding the left bone, EFEOPF was observed in more than 31% of the pre-Hispanic inhabitants, but it was absent in the modern population), in sharp contrast with the similar prevalence of some other commonly observed traits, such as the type Ia facet, which was present in about 14% of the pre-Hispanic population and 19% of the modern one. Therefore, this indicates that some traits strongly depend on different activities performed by both populations, whereas others must be dependent on a common genetic inheritance. Interestingly, no differences were observed among males and females regarding these two traits, both in the pre-Hispanic and modern samples.

The presence of EFEOPF has been attributed to different types of squatting positions, and/or high activity levels with angular ankle movements [

50]. Normally, the talo-calcaneal ligaments and the retinaculum would stop the talus from advancing into the sinus tarsi, but in a forced partial dorsiflexion, the talus can advance slightly more than usual [

51]. The facet shape has also been described in relation to anatomical variations in ligaments [

18]. The very high prevalence of this trait among the pre-Hispanic population is fully in accordance with the marked differences in lifestyle before and after the Spanish conquest, moving from agropastoralist activities to an urban way of life. It is also of interest to consider that EFEOPF was similarly common among pre-Hispanic men (i.e., 31%) and women (32% of the left bones), so both sexes performed similar activity, at least regarding the information derived from this trait.

Another striking result is the presence of a pseudo-facet, a trait that affects most of the pre-Hispanic population (88.9% among males and 86.1% among females), but only 32% of the modern one (36.1% of females and 26% of males). This trait has previously been associated with an area of friction with the talus bone in cases of flat foot syndrome [

19], although other authors suggest that it is a cervical ligament attachment site, where

the extensor digitorum

brevis muscle attaches to the calcaneus [

19], adopting the appearance of a facet, as other muscle attachments are shaped as depressions [

21]. In any case, the prevalence of this trait among the modern population of the Canary Islands is also very high (>30%), compared with that derived from other studies, such as that of Madhavi et al. [

19], who described the trait in only 4% (9 out of 225 cases) of the Indian population. Therefore, our results strongly suggest that the trait must be influenced not only by a strong muscle attachment (derived from activity), but also by genetics, since it is by far more common among both pre-Hispanic and modern Canarians than among other populations, although the higher prevalence among pre-Hispanics suggests that lifestyle may also play a role. Perhaps, the lack of supportive footwear may account for the high prevalence of this trait. As with the EFEOPF trait, the prevalence of this trait was similar among pre-Hispanic males and females.

On the other hand, an explanation for the high prevalence of calcaneus secundarius among the pre-Hispanic population is quite challenging. The calcaneus secundarius is a small accessory ossicle that can be identified as a porous notch, and is either deep, small, and semicircular, or large and shallow, usually located on the anterior facet of the calcaneus. Until now, there are no studies that have proven a hereditary transmission of the trait [

52]. It seems more likely to be a trait related to physical activity performed during childhood, similar to the pathogenesis of os trigonum in talar bones. It was found in nearly 12% of the pre-Hispanic sample (both males and females), a figure by far higher than that reported for other population groups, and only comparable with the figures observed for the French population [

53] and that (11.8%) of a Neolithic–Chalcolithic population in Portugal [

54]. Some authors argue a genetic origin, based on observations on individuals where many other ossicle-type traits are present [

53]. In the present study, the finding of only 1 case among the modern population in contrast to the 19 cases (in which sex was estimated) observed in the pre-Hispanic one strongly supports that the trait is not a genetic one, but acquired via physical activity during childhood [

40].

The retrotrochlear eminence is regarded as the insertion site for the peroneus quartus muscle [

55]. It was very frequently observed among the population studied. Overall, the prevalence of this trait is high (84%) in some studies [

56], in which its presence was evaluated dichotomically (present/absent), as undertaken in this work. However, other authors have determined its size, and considered its presence only if it reaches a given size (5 mm following [

57]), thus making comparisons difficult: [

57] reports a prevalence of 17% of total cases. Logically, one can expect that, as with other muscle insertions, the stronger the muscle, the greater the enthesis. Although it seems that the trait is slightly more frequent among the pre-Hispanics, the differences are not very marked and only restricted to right female bones—although perhaps indicating again more evidence of the higher level of exercise performed by the pre-Hispanics—and, overall, we can consider that the prevalence is in the range of reported studies, especially considering that this trait may become sometimes difficult to identify due to taphonomic alterations.

The medial root of the inferior

extensor retinaculum (MRIER) trait relates to the insertion area on the calcaneus where the fibrous tissue wraps around the ankle and inserts into the tibial malleolus on the other side of the foot [

20,

21]. Due to this trait being an insertion for a muscle, it is likely an activity marker that can indicate dorsiflexion and plantarflexion movements during life [

26]. This may explain why we found a by far larger proportion of this trait among the pre-Hispanic population (≈50%) than in the post-conquest one (≈35%). In any case, both figures are also larger than the 13.1% reported by Morimoto (1960) [

18], therefore suggesting that a genetic component also exists regarding this trait.

A similar argument may be used to explain the prevalence of the type Ib talocalcaneal facet. It is the most frequent variant, especially among the pre-Hispanic population, reaching a figure (nearly 74% among left male bones and 69% among female ones) higher than any other reported [

26,

58]. The prevalence observed among the post-conquest population is also quite high (≈40%)—higher, for instance, than that reported for the Spanish population (25%) in [

38]. It is important to consider that among individuals with type I facets, there are only two facets that support the total body weight in the ankle, reducing weight support and allowing the foot to slide, thus allowing osteoarthritis to form much more easily [

59,

60]. As the results of this study also suggest (high prevalence even in the modern population), the talo-calcaneal types have often been associated with genetic population differences in previous studies [

19,

61,

62], although acquired factors were also surely present, explaining the even higher proportion among pre-Hispanics. Thus, the differences observed in this study are likely due to other factors rather than genetics. The talo-calcaneal facet association with osteoarthritis shown in previous research [

19,

36] may be due to ankle movement and posture influencing the shape of the facets and, as a consequence, causing osteoarthritis.

It is also important to highlight the lack of statistically significant differences in prevalence among males and females regarding facet type, both in the pre-Hispanic and modern samples. Future research should focus on the factors other than genetics that influence the presence of these calcaneal traits, as well as other postcranial skeletal variations. Research focused on genetic aspects of the traits would be beneficial for kinship studies and heritability studies alike. Therefore, multidisciplinary approaches where geneticists and archaeologists collaborate to discover particular genes that influence the appearance of postcranial traits would be highly valuable for heritability studies.

A limitation of this study is the possible difference existing between the two modern Canarians samples included in this study, which may have influenced the results of this study. On one hand, the La Concepción Church collection provides skeletal individuals from multiple lifestyles from a port city environment of the 18th century, while the Convent of San Francisco of Las Palmas, Gran Canaria, is a collection that perhaps contained a larger proportion of friars. However, the convent was also a “sacred” place, and a desired place for Catholics to be buried, and, indeed, many of the individuals buried at that place were citizens living in an urban, port environment, similar to that of Santa Cruz. In any case, subtle lifestyle differences may have existed among the two sites. Another limitation is that although genetic homology was considerable between pre-Hispanic and modern individuals, the modern population is mixed, formed by people of pre-Hispanic ancestry but also Spaniards, other Europeans, some sub-Saharan Africans, and even some South American natives [

16], so we cannot fully assure that the appearance of a given trait only depends on differences in activity. However, as commented, the higher proportions of some traits, such as MRIER, both among pre-Hispanic and modern Canarians, do support the relative genetic homogeneity of pre-Hispanic and modern Canarians compared with other population groups.

Also, in this study, the most “modern” individuals analyzed were at least 200 years old. In these two centuries, some further changes in lifestyle may have occurred that may have modified the prevalence or some features of the analyzed traits, limiting the ability to apply the results obtained to forensic research on contemporary population of the Canary Islands. In any case, some traits such as the retrotrochlear eminence, EFEOPF, pseudo-facet, MRIER, talocalcaneal facets, and calsec2 are more common among pre-Hispanics. Regardless of whether these traits are highly influenced by genetics or lifestyle, they may aid in the identification of “modern” vs. pre-Hispanic skeletal remains due to the highly statistical differences shown in this study. As shown, the majority of calcaneal non-metric traits included in this study are statistically different in frequency between pre-Hispanic and modern Canarians, and thus could be used for identification. This may be useful to help separate modern forensic cases from pre-Hispanic archaeological cases.

Furthermore, the use of non-metric traits, specifically trait combinations, in individual identification has shown promising results [

12]. Therefore, following our results, it may be possible that combinations of postcranial traits, such as calcaneal variation, may aid in personal identification. Previous research has already demonstrated potential trait combinations to identify relationships in archaeological contexts [

13].