1. Introduction

On 25 January 2019, the tailings dam of an iron ore mine owned by Vale S.A. collapsed in Brumadinho, Minas Gerais, Brazil. The city is located about 50 km from Belo Horizonte, the state capital. Approximately 12 million cubic meters of mine tailings were spilled, covering an area of 290 hectares. The spill directly affected the company’s personnel, local residents, and tourists. The disaster caused 272 fatalities, a number that includes two unborn babies. It is considered the largest occupational accident and one of the most severe environmental disasters in Brazil’s history [

1,

2,

3].

The term ‘disaster’ is defined by the International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL) as an unexpected event causing the death of multiple victims and can be classified as either open or closed [

4]. Disasters are classified as open when the number and identity of the victims are unknown and the lack of information requires further investigation. In contrast, closed disasters involve victims who belong to a known group with available reference information [

4]. The Brumadinho disaster fits both categories, as it affected not only areas with registered workers but also residential and rural areas where there was no pedestrian traffic control [

2].

To guide the process of human identification in the context of catastrophes, INTERPOL created the Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) guide. The guide provides recommendations and establishes a standard on how to conduct DVI operations worldwide. An identification is based on the confrontation (reconciliation) between postmortem (PM) data, obtained through the examination of the mortal remains, and antemortem (AM) data, obtained from healthcare professionals, public and private databases, as well as interviews with family and friends.

PM data include clothing and belongings, photographs, fingerprints, medical and dental imaging, DNA samples, and PM procedures (necropsies); on the other hand, AM data include information on clothing and belongings, medical and dental records and imaging, photographs, posts on social media, DNA samples, and particular identification marks, such as tattoos. The confrontation is considered positive when there is correspondence between PM and AM data, allowing the victim’s identity to be confirmed [

4].

The most reliable identifiers to confront in the process of identification are considered primary methods: fingerprints, dental records, and DNA. Alternatively, any other identifier capable of characterizing an individual in any way is considered a secondary method, a resource mainly used to reinforce an already established identity by means of a primary method. However, depending on the context of the analysis, secondary methods may become the protagonists in the case of a non-successful identification attempt with primary methods, limited access to primary identifiers or non-existent primary identifiers. Moreover, the quality of the data is a determining factor in the choice of which identification method will be the most appropriate for each case [

4].

The identification of unknown bodies is one of the most important objectives of forensic sciences [

5]. This procedure is indispensable for many reasons, including its legal and administrative importance for the state, as well as the moral and humane commitment towards the deceased and their families [

6]. For some people, grief begins with the suspicion of death. For others, the uncertainty of death is harder to deal with than its confirmation; in such cases, the confirmation of death is a prerequisite for grief [

6,

7]. Therefore, in response to the Brumadinho DVI, the Brazil’s largest task force dedicated to the search, localization, and identification of victims was created [

1,

2,

8]. In this context, the Instituto Médico Legal Dr. André Roquette (IMLAR) of the Polícia Civil de Minas Gerais provided the infrastructure and personnel, among other resources, to carry out the collection and confrontation of PM and AM data to ascertain the identity of the victims of the disaster. With this initiative, the victims’ mortal remains could be returned to hundreds of families, allowing them to say goodbye to their beloved ones and pay their last homage [

8,

9].

Tattoos can be invaluable identifiers. Some of the fundamental characteristics that make tattoos a useful resource in the process of body identification include their stability and relative durability, the fact they can be easily reported during the necroscopic exam, the possibility of being found in body fragments, and the low cost and fast performance of this confrontation method [

6,

10,

11]. These attributes are particularly significant in challenging forensic cases, including burnt human remains, extensive fragmentation, and other scenarios encountered in Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) or routine forensic investigations.

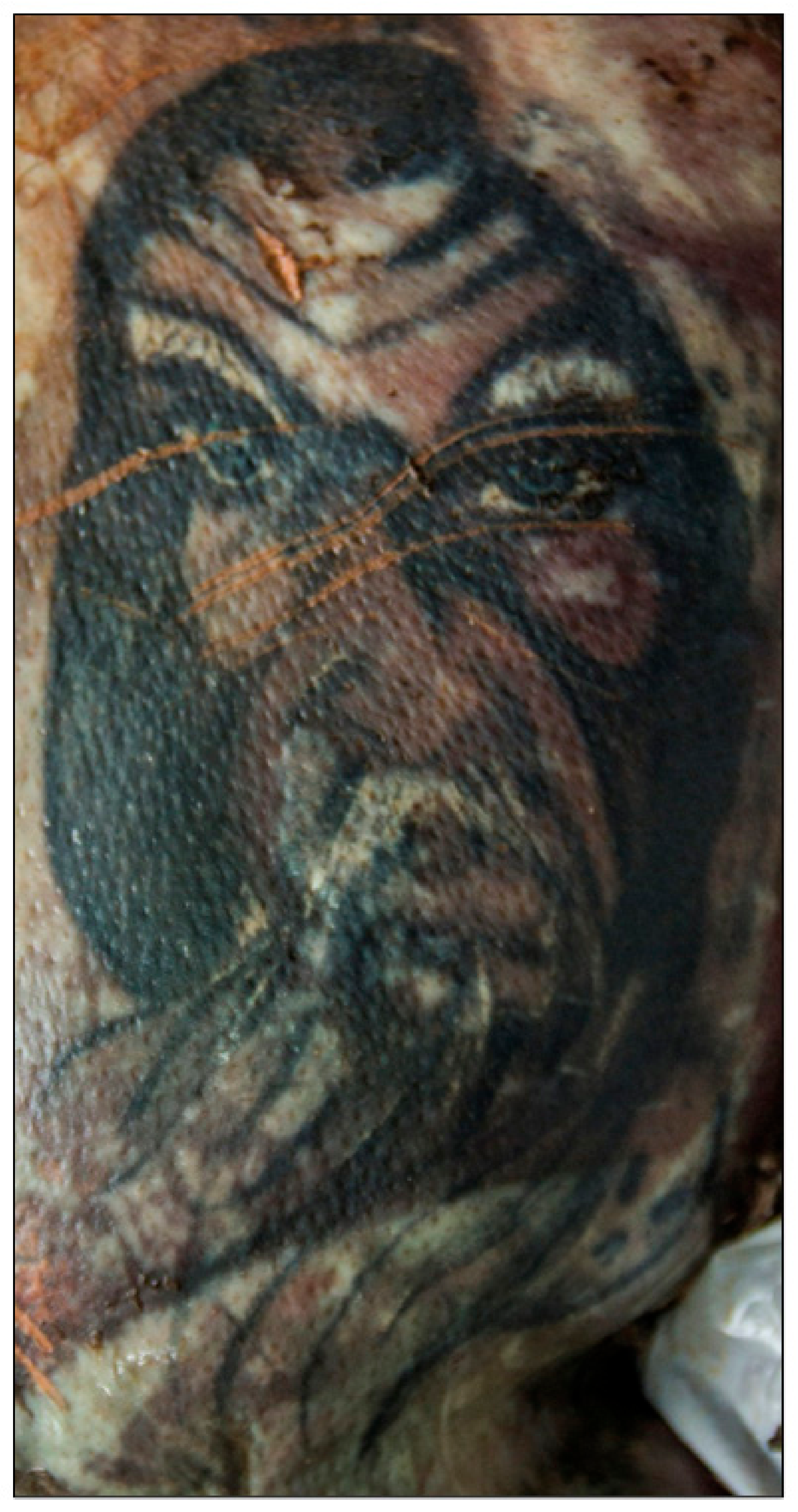

Even when dealing with a catalog tattoo reproduced by the same tattoo artist on two different individuals, there are noticeable differences in aspects such as linework, pigment intensity, and inclination. These variations arise due to the unique characteristics of each individual’s skin, the pressure applied by the tattoo artist, and other subtle factors. With the use of macro lenses for PM records and the advancements and accessibility of smartphone cameras, mostly used for AM pictures, these differences have become increasingly perceptible. Just as there is specialized expertise in authenticating a work of art or verifying the authenticity of a signature, the forensic analysis of tattoos operates on the same principle. It is precisely these distinct details that form the basis for identification through the comparison of tattoo records.

This work assesses the utilization of the comparative exam of tattoos as an identification method based on two cases of the Brumadinho DVI, carried out by medical examiners from IMLAR’s Forensic Anthropology Division (SAF). The cases presented had authorization for the use of images for exclusive scientific and teaching purposes signed by the family members responsible for removing the bodies from IMLAR, and the study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculdade Ciências Médicas de Minas Gerais.

3. Discussion

Tattoos are permanent markings created by perforating the skin and injecting ink into the dermis [

10,

12], a practice that dates to prehistoric times [

10,

13,

14]. Historically, tattoos have served as identifying traits for various groups, including “barbarian tribes”, Christians, “freak show” performers, slaves, marginalized individuals, sailors, criminals, prostitutes, and military personnel [

10,

12,

13,

14]. However, the migrations, social transformations, and cultural amalgamations associated with the progression of civilization have led to a shift in the motivations behind tattooing, contributing to the deconstruction of related stereotypes [

10]. Today, tattoos are often considered a form of body art, created with custom designs on various anatomical regions, carrying symbolic significance and frequently commemorating important life events for their bearers [

6,

10,

13,

15].

Tattoo pigments are deposited in the dermis layer of the skin, allowing them to remain visible even after exposure to treatments, immersion in liquids, burns, or decomposition [

11,

14,

15,

16]. In some cases, the detachment of the epidermis can even enhance the visibility of the tattoo’s colors [

11]. Additionally various techniques can improve the visualization of unclear tattoos. These include radiographic examination, particularly useful for older tattoos created with metallic inks [

11]; the direct application of a 3% hydrogen peroxide solution, despite its potential for tissue destruction [

11]; and infrared photography, which enhances black and green pigmentation [

6,

11].

Tattoos have become increasingly popular in Western countries, with prevalence rates estimated at 10–16% among teenagers and 3–9% in the general population [

12,

13,

15,

17]. A recent study conducted at the Instituto Jalisciense de Ciencias Forenses (IJCF) in Mexico reported an even higher prevalence of tattoos among bodies admitted to legal medical institutes, with 45.8% of individuals aged 15 to 87 years displaying tattoos. Notably, individuals aged 20–29 years exhibited the highest prevalence, with 67.9% of males and 61.2% of females having tattoos [

18]. Furthermore, the reduction in prejudice historically associated with tattoos has contributed to a rise in tattoos placed on anatomical sites that are less or not at all concealed by clothing, making them more visible. Supporting this observation, the same study revealed that 63.3% of male and 74.2% of female tattooed bodies had tattoos located on body segments considered exposed [

18].

In parallel, technological advancements have increased the social visibility of individuals. The widespread availability of personal (e.g., cameras, cell phones) and collective (e.g., security cameras) electronic devices capable of producing high-quality images and videos, along with the growing use of social media platforms to share such images, has further contributed to the identification and exposure of tattoos, potential AM resource.

The increasing number of tattooed individuals, combined with the greater visibility of tattoos on the body and the enhanced exposure of individuals on social media, has expanded the possibilities for utilizing these distinctive markers. In forensic contexts, tattoo comparison has already been employed to aid in solving crimes involving living suspects and in the identification of bodies. Examples of such applications have been reported in countries including Germany, Australia, Brazil, and the United States [

11,

13,

14,

15]. Concurrently, there has been a rise in the number of unidentified bodies, attributed to factors such as the growing population of unsheltered individuals, increased migration and travel, and disasters involving multiple victims or natural catastrophes, such as the 2004 tsunami in Thailand [

10]. Consequently, the potential applications of tattoos as an identifier warrant further exploration.

In the Brumadinho DVI, the immense mass of tailings transferred significant kinetic energy to the victims. This caused devastating mechanical effects, reducing most bodies to fragments. The prolonged recovery of mortal remains trapped under the iron ore tailings further complicated the process. The inevitable progression of decomposition and the environmental impact of elements in the tailings mud also damaged biological tissues. As a result, the quality of the recovered postmortem (PM) data was severely compromised.

These challenges were amplified by the large number of victims and the dual characteristics of both open and closed disasters. This combination disrupted the collection of antemortem (AM) data. Together, these factors made the identification process extraordinarily difficult. Various identifiers and methods were employed based on their effectiveness in each specific case. Their selection considered the quality of available data as well as the time and resources needed for analysis [

1,

2,

3,

8,

9].

In the present case series, despite the bodies being in different stages of decomposition, the anatomic sites of the tattoos remained sufficiently preserved from the traumatic forces, allowing examination. In both cases, family reference samples and AM genetic material from the suspected victims were collected for potential comparison. Biological tissue from the bodies was also preserved for postmortem (PM) DNA extraction to enable future analyses. While DNA identification was one of the primary methods used in the Brumadinho DVI [

2], this approach faces challenges, including DNA degradation due to decomposition and the harmful effects of iron ore tailings [

19]. Additionally, DNA analysis requires substantial time, financial resources, and logistical efforts [

6]. In cases involving multiple victims, faster and more cost-effective methods are crucial.

Given these constraints and the availability of preserved tattoos, the comparative examination of tattoos was chosen as the most suitable identification method for these cases. During necropsy, the tattoos (PM) were easily identified without requiring physical treatment for visualization. Photographic records (PM) were digitally adjusted to match the dimensions of AM images, enabling simpler and more precise comparisons.

In case 1, fingerprint identification was also performed, corroborating the results of the tattoo comparison. For case 2, while no PM data for dental or fingerprint-based methods were available, the identification by tattoos was later confirmed using dental records from another body segment brought to the IMLAR.

Regarding AM data, several challenges were noted. Tattoo descriptions were inherently subjective, influenced by the perspectives of both AM reporters and PM examiners [

6,

15]. Additionally, AM tattoo reports were brief, making purely descriptive comparisons inconclusive. Despite these limitations, access to up-to-date AM images was critical for the identification process [

11]. Social media, while often criticized for overexposure, proved instrumental in case 1 by providing a photograph essential for comparison. Without this image, AM data collection would have been impossible.

Notably, the low quality of AM data in both cases did not hinder the effectiveness of the comparative examinations. The proactive approach of a dedicated team was key, ensuring an active search for AM materials and diligent data confrontation. The examinations compared PM and AM images to identify coincident points while avoiding exclusion of features. This method followed established practices used in comparative dental exams and the radiographic or tomographic imaging of frontal sinuses. The results were unequivocal, successfully establishing the victims’ identities.

This highlights that, while DNA is often regarded as the gold standard in Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) due to its reliability and precision, alternative methods may still hold significant value [

20]. According to the most recent edition of the DVI guide, INTERPOL acknowledges that secondary identification methods, including tattoos, can, depending on the circumstances, serve as standalone identification methods [

4].

Tattoos, in particular, may provide a distinct and highly reliable means of confirming identity, especially when they feature unique patterns, designs, or inscriptions that are easily verifiable. This flexibility underscores the importance of a context-driven approach in DVI, ensuring the most effective and timely identification process possible. Similarly, the existing literature supports the use of tattoo comparison as an independent method of identification [

6,

18]. The value of morphological methods for identifying unknown bodies is widely acknowledged [

6,

18].

While tattoos are often viewed as storytelling features, reflecting an individual’s life experiences and identity, they can also be regarded as objective morphological characteristics. These features persist after death and can be effectively used to confirm the identity of both living and deceased individuals [

6,

18].

In addition to the cases presented in this study, SAF/IMLAR documented other instances of successful identification through the meticulous AM/PM comparisons of tattoos and the analysis of medical radiological documentation [

21]. This approach proved effective, not only in other cases from the Brumadinho DVI response, but also in various forensic contexts, highlighting its reliability and adaptability in complex identification scenarios.

Similar to dental analysis and identification through medical findings, these comparisons were conducted using rigorous scientific procedures, ensuring their validity, reliability, and reproducibility [

21,

22].

Further advancements are anticipated as automated matching and retrieval systems become more widely available and increasingly feasible for identification and forensic authentication purposes [

12,

23,

24,

25]. These systems are already utilized to assist in the identification and search for tattoos on living individuals [

26,

27]. Although their application in the matching and identification of postmortem tattoos demonstrates significant potential, the authors hope it will become the focus of increasing research efforts.