Investigation of the Microwave Absorption Properties of Bi1.7Pb0.3Sr2Ca2Cu3O10-Based Ceramic Composites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Preparation

2.1. Material Synthesis

2.2. Superconducting and SEM Properties

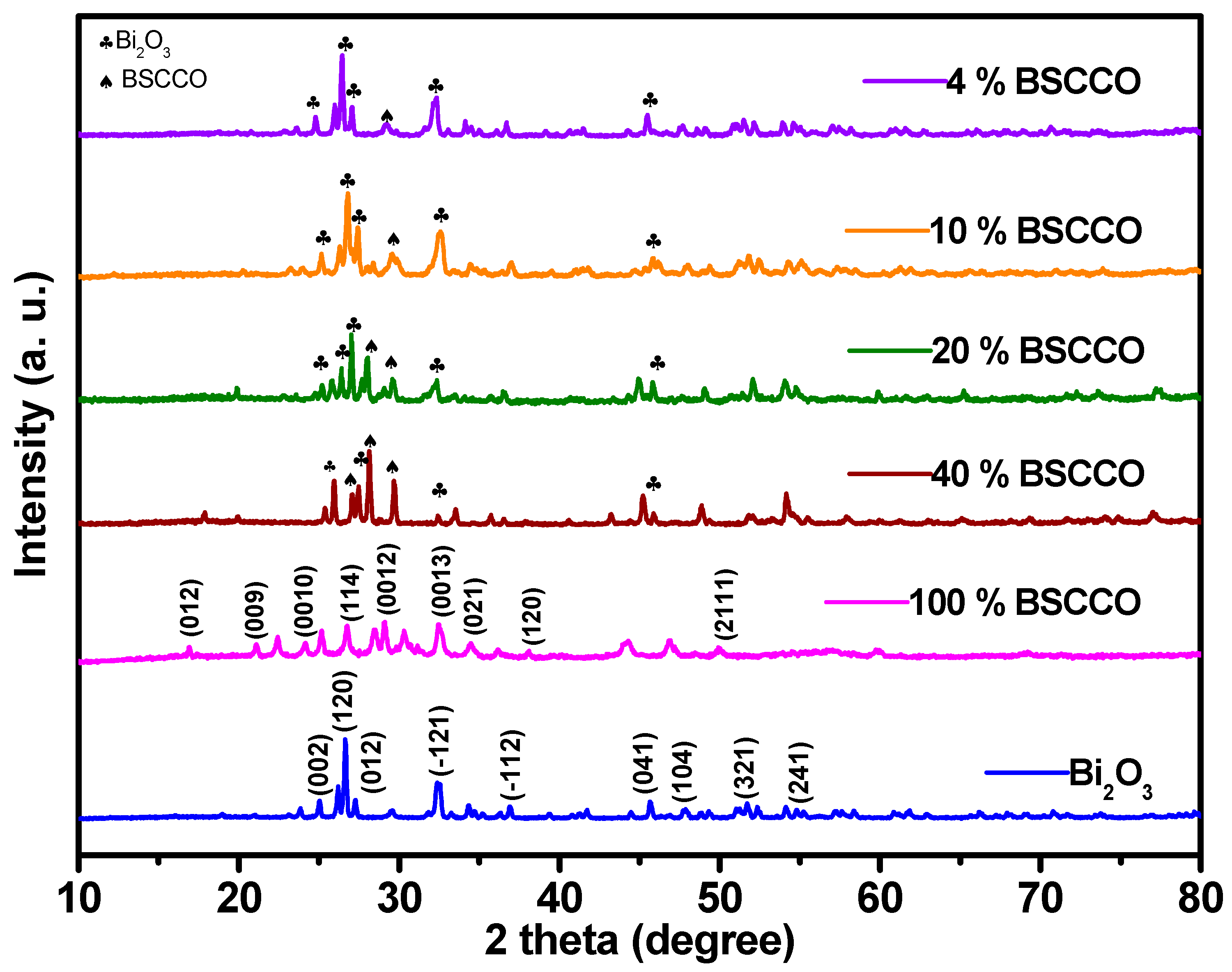

2.3. Crystalline Structures

3. Microwave Absorption

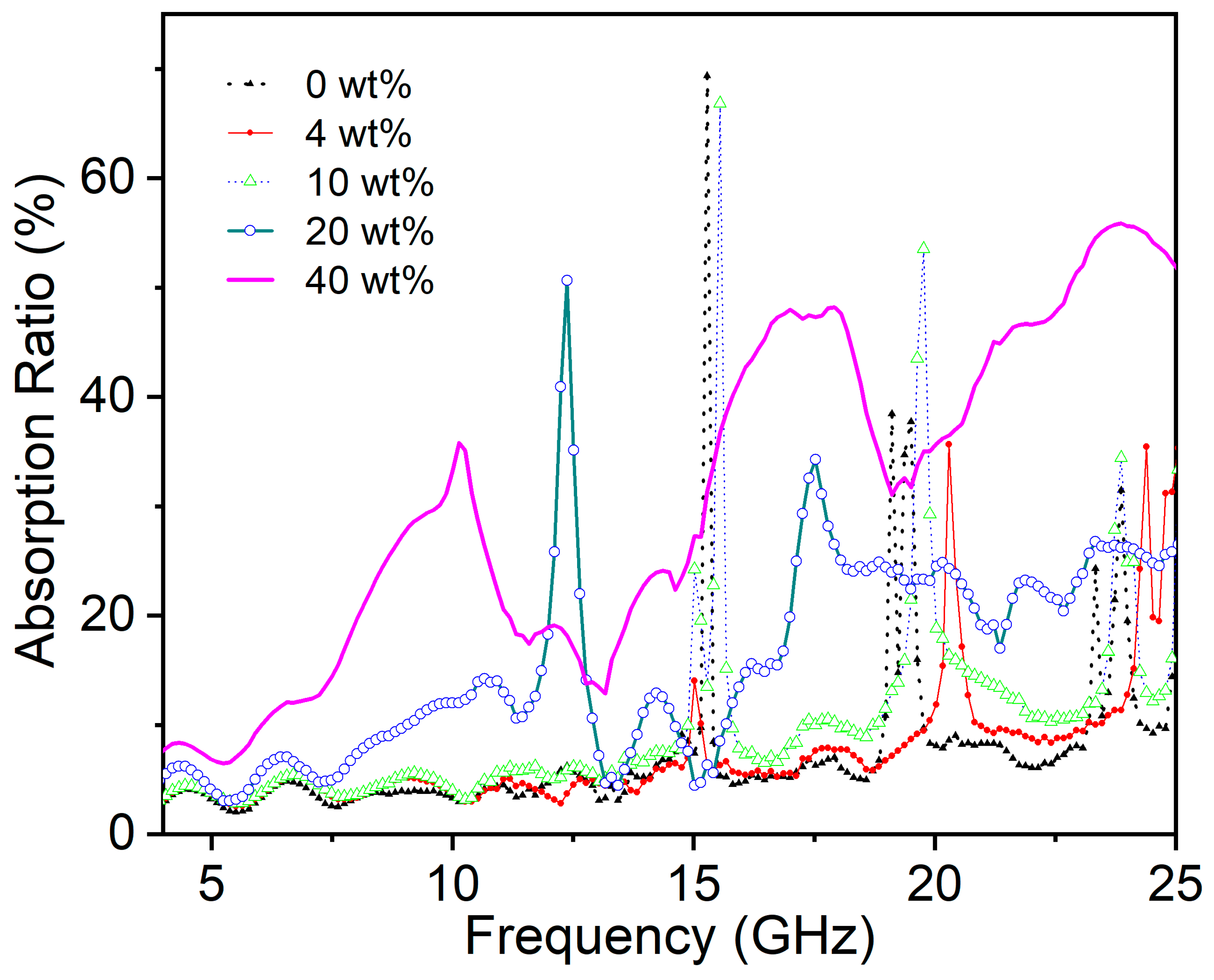

3.1. Reflection, Transmission, and Absorption Properties

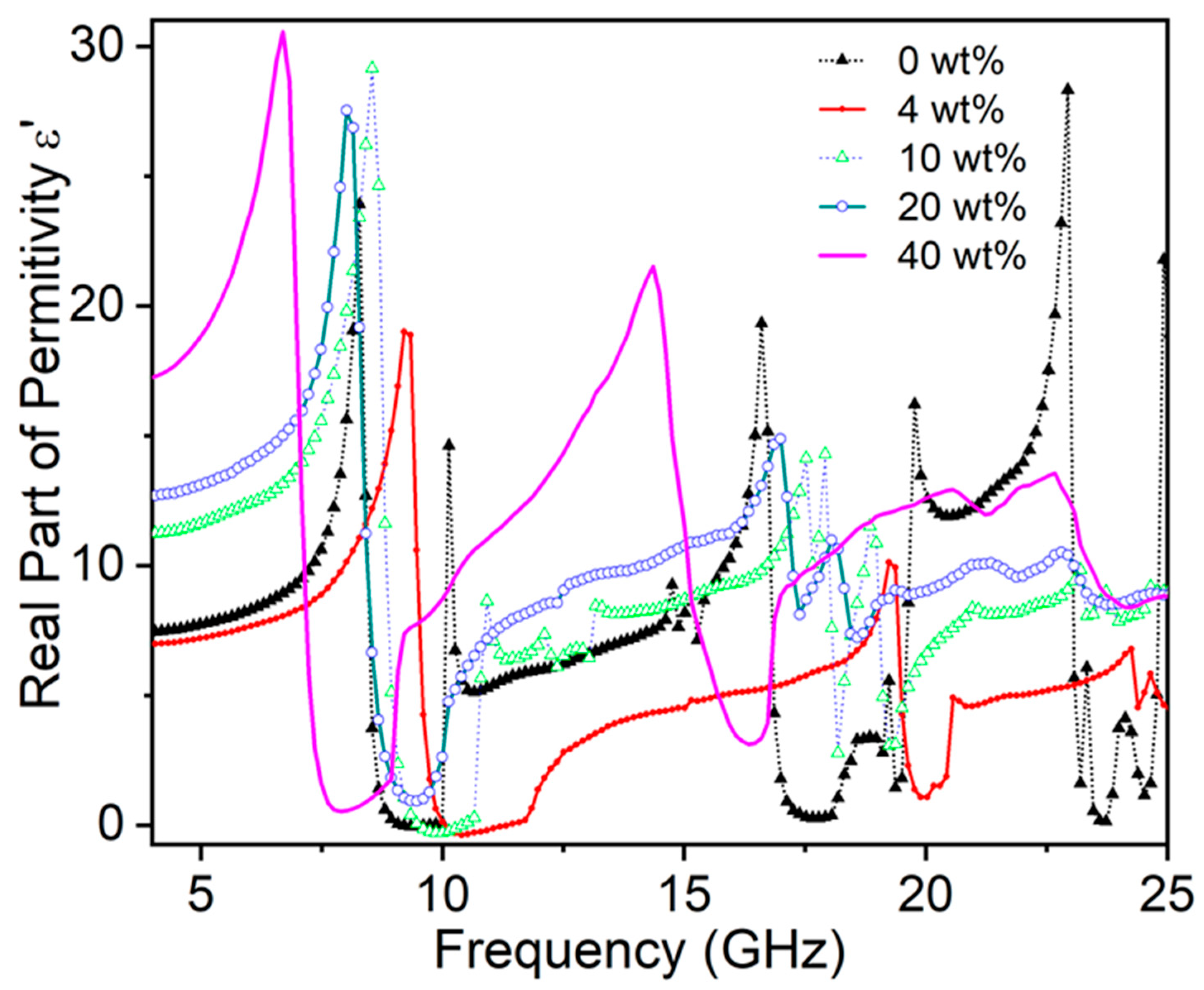

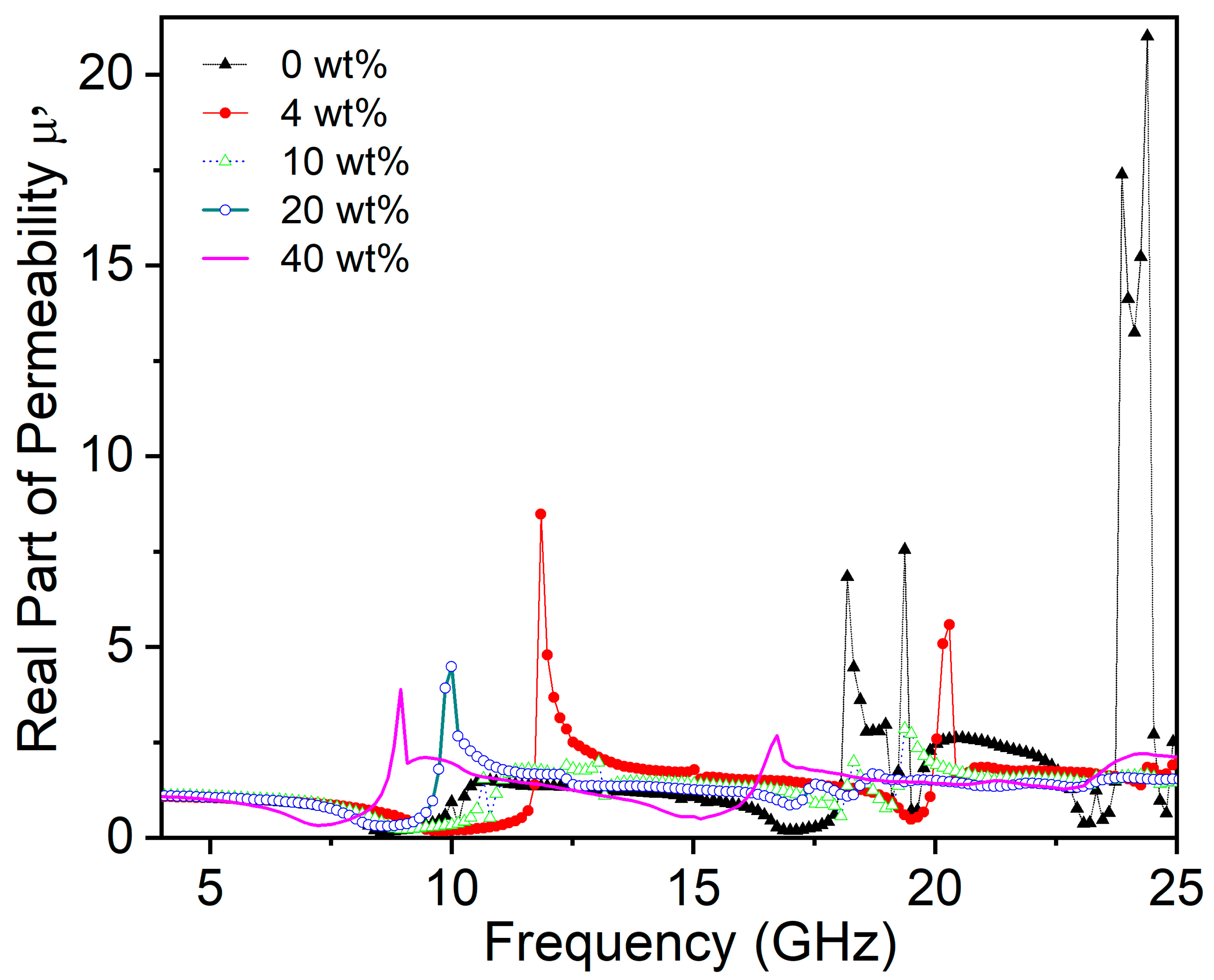

3.2. Dielectric and Magnetic Properties

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EM | Electromagnetic |

| EMI | Electromagnetic Interference |

| RF | Radio Frequency |

| MAM | Microwave Absorption Material |

| PPMS | Physical Property Measurement System |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| RL | Reflection Loss |

| XRD | X-Ray Diffraction |

References

- Zang, X.; Lu, Y. Preparation and dielectric properties at high frequency of AlN-based composited ceramic. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2020, 31, 2826–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; He, M.; Zhan, B.; Guo, H.; Yang, J.L.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, J. Multifunctional microwave absorption materials: Construction strategies and functional applications. Mater. Horiz. 2024, 11, 5874–5894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Kong, L.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, L.; Travitzky, N.; Greil, P. Electromagnetic properties of Si–C–N based ceramics and composites. Int. Mater. Rev. 2014, 59, 326–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, J.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Y.; Yao, D. Structure, magnetic and microwave absorption properties of NiZnMn ferrite ceramics. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2021, 534, 168043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Yin, X.; Li, Q.; Schlier, L.; Greil, P.; Travitzky, N. A review of absorption properties in silicon-based polymer derived ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2016, 36, 3681–3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Jo, S.B.; Gueon, K.I.; Choi, K.K.; Kim, J.M.; Churn, K.S. Complex permeability and permittivity and microwave absorption of ferrite-rubber composite at X-band frequencies. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1991, 27, 5462–5464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, D.; Bhandari, B.; Mullurkara, S.V.; Ohodnicki, P.R. All-around electromagnetic wave absorber based on Ni–Zn ferrite. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 33846–33854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, L.; Han, Y.; Liu, P.; Xu, H.; Yu, G.; Wang, Y.; Wen, T.; Ju, W.; Gu, J. Hierarchical construction of CNT networks in aramid papers for high-efficiency microwave absorption. Nano Res. 2023, 16, 7801–7809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Jia, D.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, Y. Principles, design, structure and properties of ceramics for microwave absorption or transmission at high-temperatures. Int. Mater. Rev. 2022, 67, 266–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Petersen, E.J.; Pellegrin, B.; Gorham, J.M.; Lam, T.; Zhao, M.; Sung, L. Impact of UV irradiation on multiwall carbon nanotubes in nanocomposites: Formation of entangled surface layer and mechanisms of release resistance. Carbon 2017, 116, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhasha, B.; Gautam, S.; Malik, P.; Jain, P. Ceramic composites for aerospace applications. Diffus. Found. 2019, 23, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfini, A.; Albano, M.; Vricella, A.; Santoni, F.; Rubini, G.; Pastore, R.; Marchetti, M. Advanced radar absorbing ceramic-based materials for multifunctional applications in space environment. Materials 2018, 11, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Wei, Q.; Ding, Y.; Wang, H.; Ma, C.; Yuan, K.; Han, D.; Wang, H.; Zhang, R.; Shao, G. Integration of microwave absorption capability into mullite insulation tiles for multifunctionality. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2025, 22, e15090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, B.; Chai, Z.H.; Li, M.; Duan, J.J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.B.; Li, C.P.; Gong, C.H. Design of mesoscopic metacomposites for electromagnetic wave absorption: Enhancing performance and gaining mechanistic insights. Soft Sci. 2025, 5, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Li, E.; Xia, G.; Xie, N.; Shen, Z.Y.; Moskovits, M.; Yu, R. Silica-based ceramics toward electromagnetic microwave absorption. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 41, 7381–7403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeni, J.O.; Ma, S.; Wang, X.; Hou, X. Fabrication method, dielectric properties, and electromagnetic absorption performance of high alumina fly ash-based ceramic composites. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 21268–21282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yin, X.; He, Q. Microwave absorption performance of porous heterogeneous SiC/SiO2 microspheres. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 451, 138742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Mao, B.; Huang, H.; Wang, X.; He, T. Synthesis and microwave absorption properties of bamboo-like β-SiC nanowires. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2020, 17, 1869–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.K.; Mishra, R.R. Role of particle size in microwave processing of metallic material systems. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2018, 34, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.; Liu, Z.; Xiang, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, M.; Tan, X.; Huang, F.; Liu, L.; Chen, X. Doped, conductive SiO2 nanoparticles for large microwave absorption. Light. Sci. Appl. 2018, 7, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudáková, N.; Macko, D.; Szabó, P.; Samuely, P.; Plecháček, V. Study of energy gap features in BSCCO superconductors. Phys. C Supercond. 1994, 235, 1125–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, K.; Neaton, J.B.; Ashcroft, N.W. First-principles study of adhesion at Cu/SiO2 interfaces. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 68, 125403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholodkova, A.; Smirnov, A.; Danchevskaya, M.; Ivakin, Y.; Muravieva, G.; Ponomarev, S.; Fionov, A.; Kolesov, V. Bi2O3-modified ceramics based on BaTiO3 powder synthesized in water vapor. Inorganics 2020, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Wang, J.H. Effect of compressive reorientation on the Tc and Jc of the superconducting composite AgxBi1.7Pb0.3Sr2Ca2Cu3O10. J. Mater. Sci. Lett. 1991, 10, 1139–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.B.; Shi, H.G.; Cao, M.; Wang, T.; Zhao, H.B.; Wang, Y.Z. Porous carbon materials for microwave absorption. Mater. Adv. 2020, 1, 2631–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Qian, Y.; Xia, J.; He, Z.; Sun, S.; Fan, M.; Zhang, Q. Superconductivity and phases of leaded Bi-Ca-Sr-Cu-O system. Solid. State Commun. 1988, 68, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.N.; Awang Kechik, M.M.; Kamarudin, A.N.; Talib, Z.A.; Baqiah, H.; Kien, C.S.; Pah, L.K.; Karim, M.K.A.; Shabdin, M.K.; Shaari, A.H.; et al. Microstructure and superconducting properties of Bi-2223 synthesized via co-precipitation method: Effects of graphene nanoparticle addition. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmahaishi, M.F.; Azis, R.S.; Ismail, I.; Muhammad, F.D. A review on electromagnetic microwave absorption properties: Their materials and performance. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 20, 2188–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupka, J. Materials with negative permittivity or negative permeability—Review, electrodynamic modelling, and applications. Materials 2025, 18, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Qiao, M.; Lu, X.; Li, Y.; Ma, Y.; Kang, B.; Quan, B.; Ji, G. Evolution of dielectric loss-dominated electromagnetic patterns in magnetic absorbers for enhanced microwave absorption performances. Nano Res. 2021, 14, 4006–4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K. Present status and future perspective of high-temperature superconductors. SEI Tech. Rev. Engl. Ed. 2008, 66, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.R.; Qiu, L.P.; Gao, S.L.; Zheng, Q.H.; Cheng, G.T.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, T.T.; Han, W.P.; Ramakrishna, S.; Long, Y.Z. Preparation and magnetic properties of BSCCO superconducting nanofibers by electrospinning and solution blowing spinning. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2022, 35, 2755–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | 1st RL Peak | 2nd RL Peak | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value [dB] | Peak Position [GHz] | Effective Bandwidth [GHz] | Value [dB] | Peak Position [GHz] | Effective Bandwidth [GHz] | |

| 0 wt.% | −14.0 | 10.3 | 1.45 | −28.7 | 18.6 | 1.19 |

| 4 wt.% | −32.6 | 12.5 | 2.51 | −20.8 | 20.2 | 2.64 |

| 10 wt.% | −23.3 | 11.3 | 1.98 | −14.9 | 19.2 | 1.06 |

| 20 wt.% | −30.7 | 10.0 | 1.46 | −19.4 | 18.6 | 1.98 |

| 40 wt.% | −11.0 | 9.08 | 0.523 | −12.1 | 23.7 | 1.45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roubion, S.; Sharma, K.P.; Dhakal, G.; Zhao, G.-L. Investigation of the Microwave Absorption Properties of Bi1.7Pb0.3Sr2Ca2Cu3O10-Based Ceramic Composites. Solids 2025, 6, 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/solids6040067

Roubion S, Sharma KP, Dhakal G, Zhao G-L. Investigation of the Microwave Absorption Properties of Bi1.7Pb0.3Sr2Ca2Cu3O10-Based Ceramic Composites. Solids. 2025; 6(4):67. https://doi.org/10.3390/solids6040067

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoubion, Sean, Krishna Prasad Sharma, Ganesh Dhakal, and Guang-Lin Zhao. 2025. "Investigation of the Microwave Absorption Properties of Bi1.7Pb0.3Sr2Ca2Cu3O10-Based Ceramic Composites" Solids 6, no. 4: 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/solids6040067

APA StyleRoubion, S., Sharma, K. P., Dhakal, G., & Zhao, G.-L. (2025). Investigation of the Microwave Absorption Properties of Bi1.7Pb0.3Sr2Ca2Cu3O10-Based Ceramic Composites. Solids, 6(4), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/solids6040067