The Antibacterial Effect of Eight Selected Essential Oils Against Streptococcus mutans: An In Vitro Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

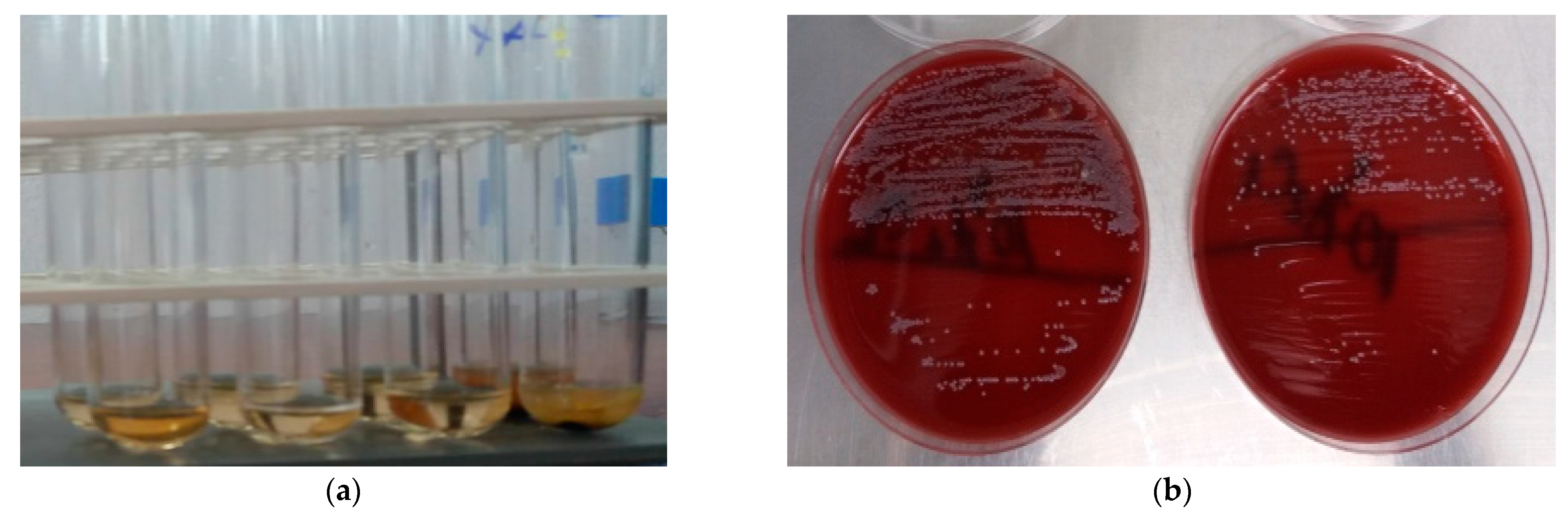

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Saliva Samples

2.2. Characteristics of the Selected EOs

2.3. Assessing the Antimicrobial Activity of the Selected EOs

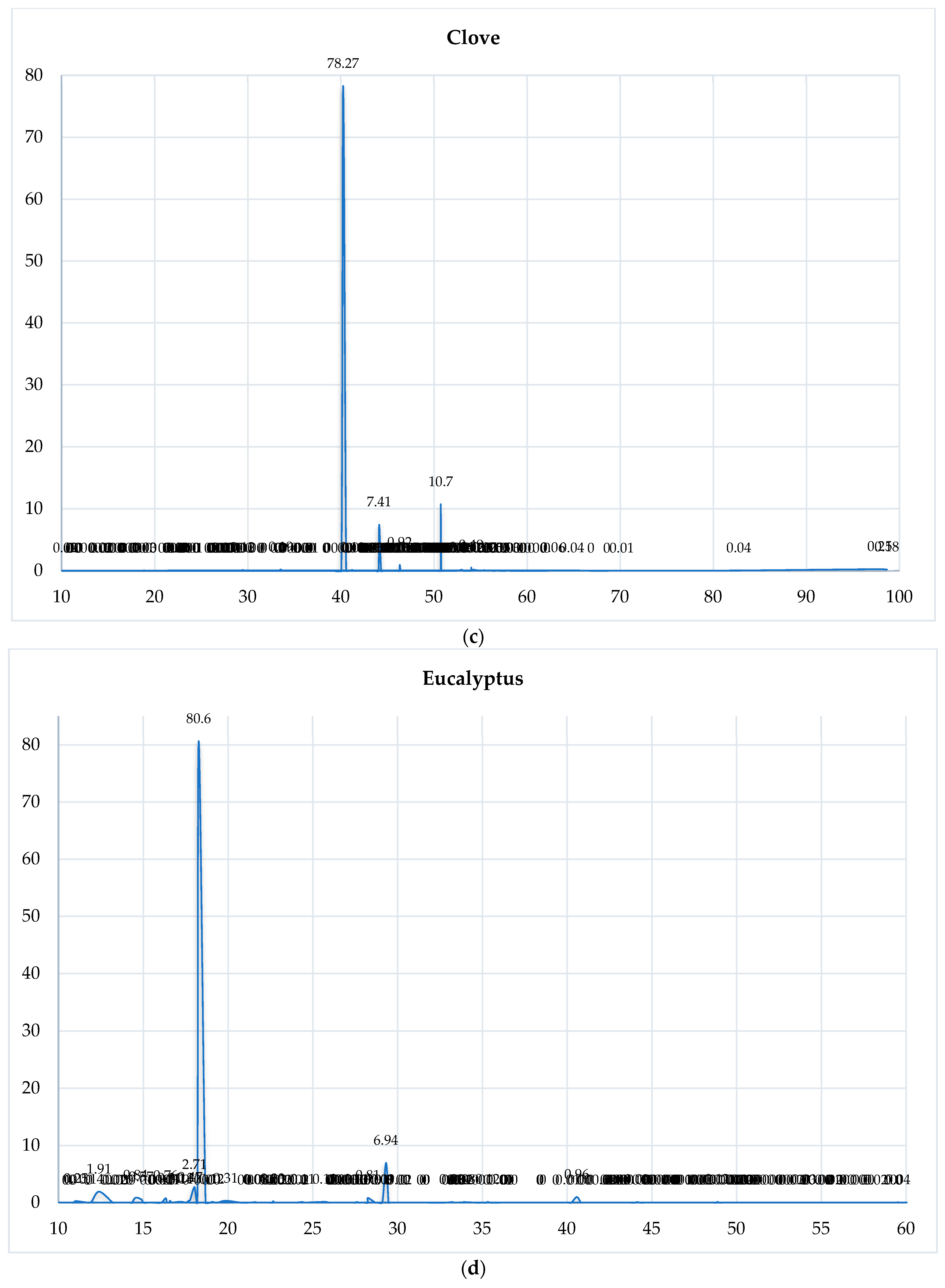

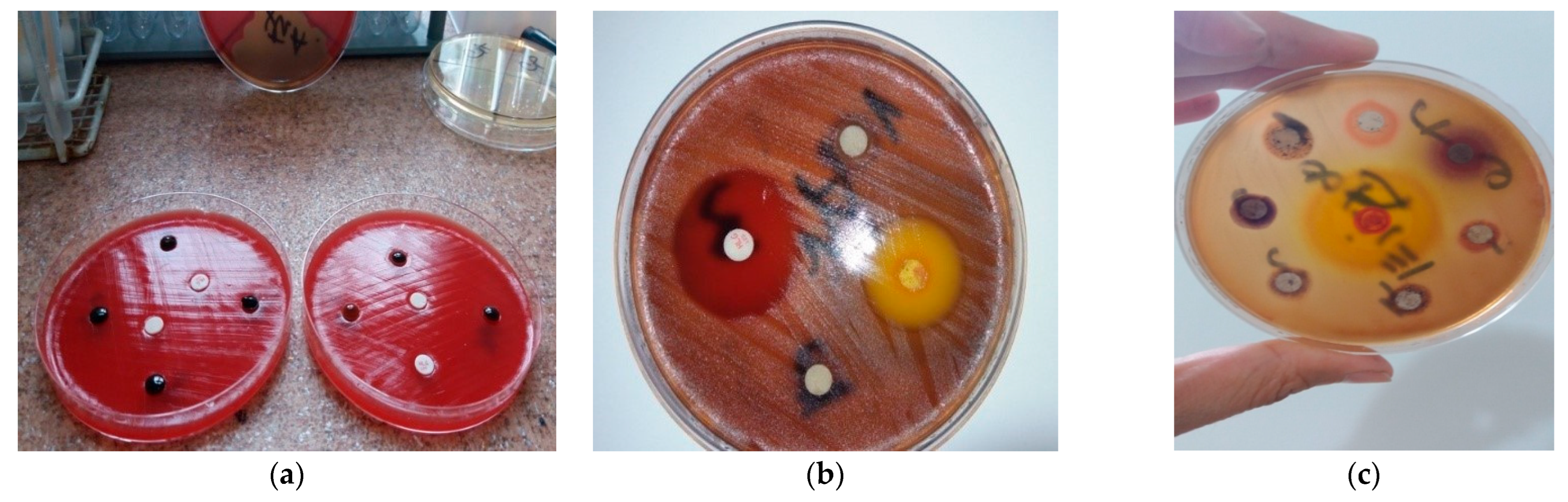

2.3.1. The Kirby–Bauer Method

2.3.2. The Broth Dilution Method

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

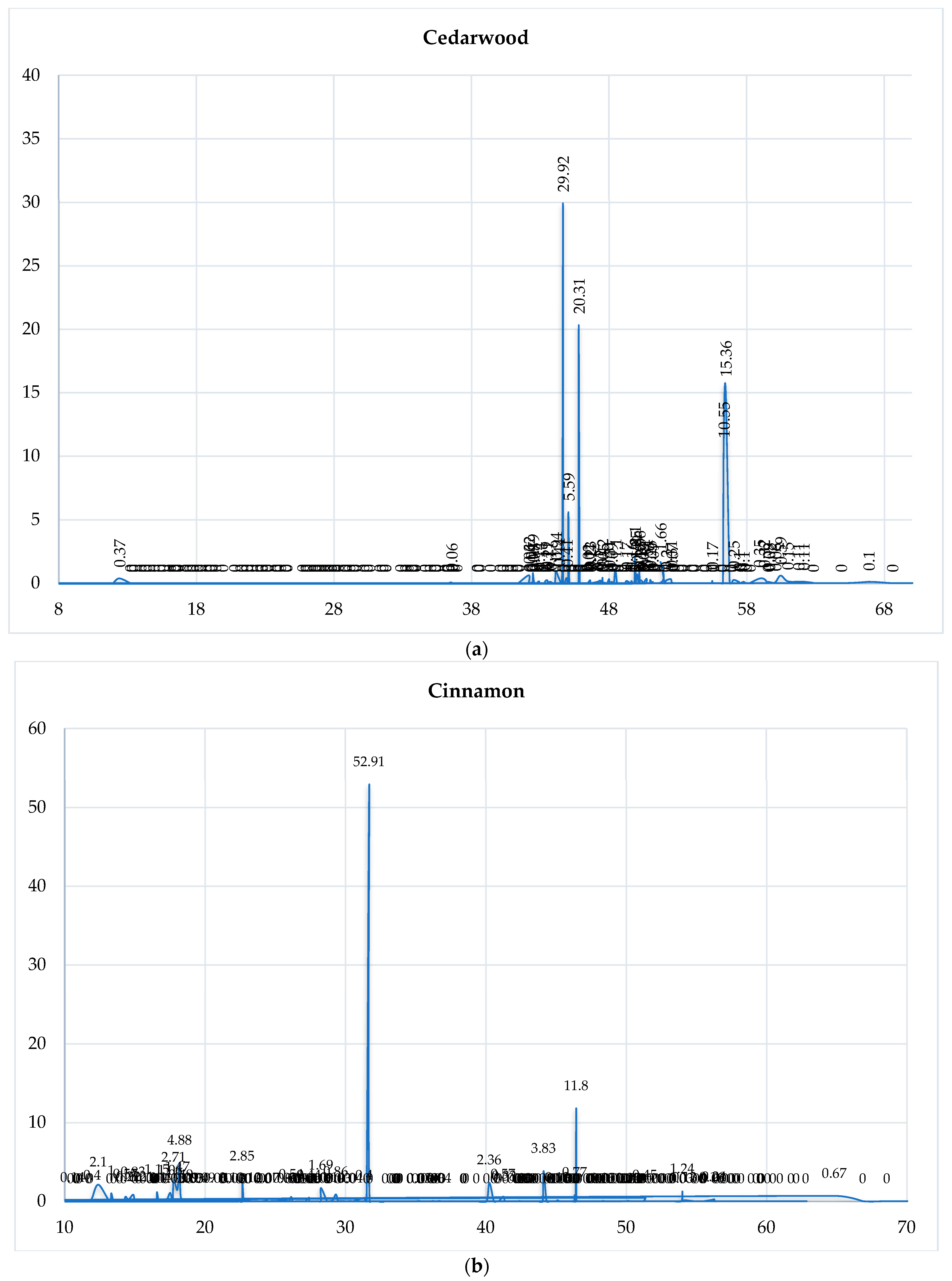

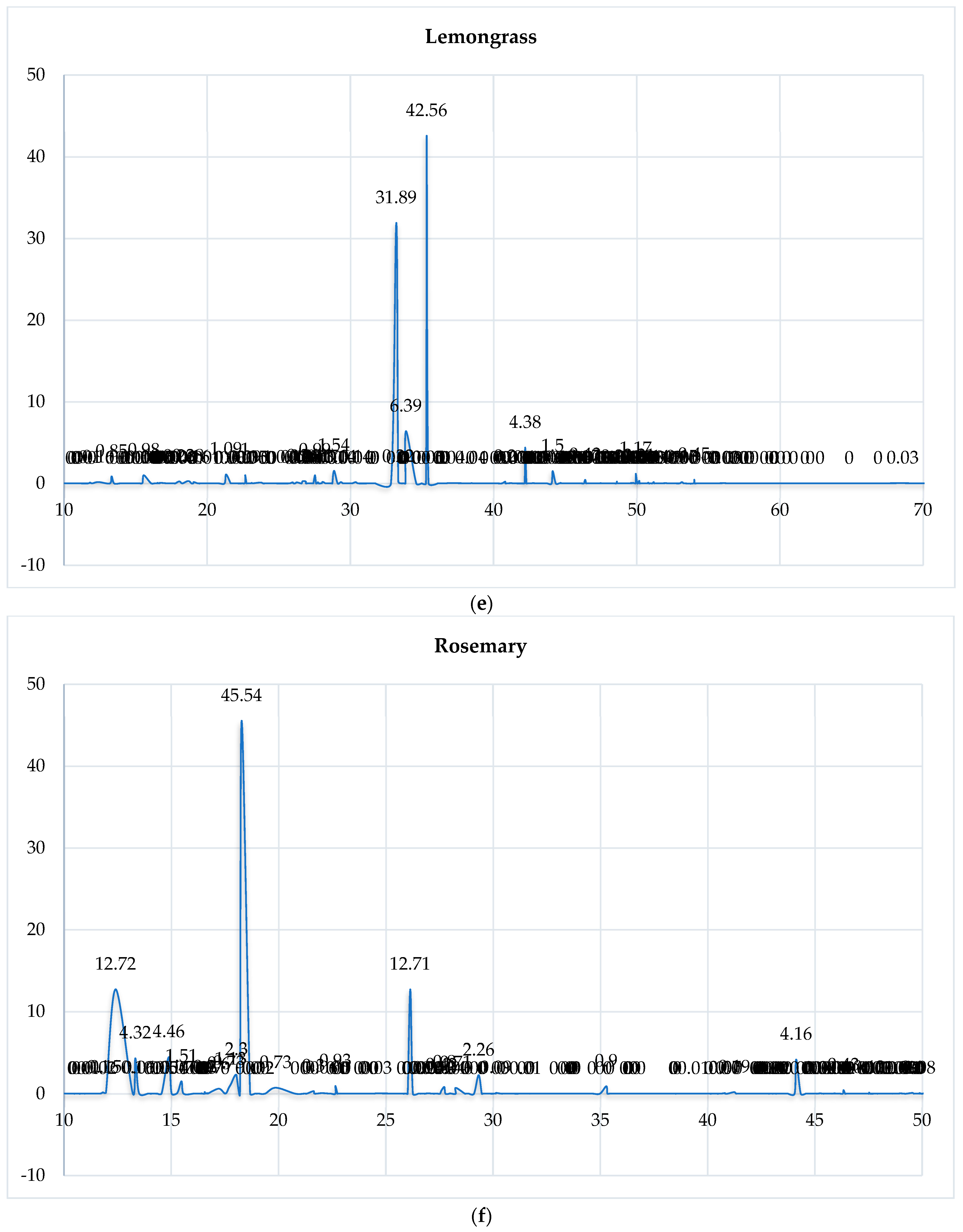

3.1. GC-MS Analysis of the Selected EOs

3.2. The IZ Determined by the Kirby–Bauer Method

3.3. The MIC and MBC Determined by the Broth Dilution Method

3.4. Statistical Analysis

3.4.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.4.2. Chemical Diversity Analysis

3.4.3. Chromatographic Reconstruction and Comparison

3.4.4. Correlation Between Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Activity

3.4.5. Comparative Statistical Analysis

Principal Component Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EO | essential oil |

| IZ | inhibition zone |

| MIC | minimum inhibitory concentration |

| MBC | minimum bactericidal concentration |

| CG-MS | Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry |

| MALDI-TOF MS | Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry |

| EUCAST | European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| RT | retention time |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| CHX | chlorhexidine |

Appendix A

| Name | RT | Cedarwood (ra%) | Cinnamon (ra%) | Clove (ra%) | Eucalyptus (ra%) | Lemongrass (ra%) | Rosemary (ra%) | Spearmint (ra%) | Tea Tree (ra%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Furfural | 8.108 | 0.11 | |||||||

| 2-trans-Hexenal | 8.728 | 0.03 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Cyclofenchene + 4-cis-Hexenol | 9.862 | 0.01 | |||||||

| 2-Heptanone | 10.417 | 0.02 | |||||||

| Styrene | 10.565 | 0.14 | |||||||

| 2,5Diethyl tetrahydrofuran | 10.809 | 0.08 | |||||||

| Bornylene | 10.897 | 0.01 | |||||||

| 4-Methyl-2-pentyl acetate | 11.027 | 0.25 | |||||||

| Hashishene | 11.701 | 0.02 | 0.08 | ||||||

| Tricyclene | 11.812 | 0.10 | 0.16 | ||||||

| alpha-Thujene | 11.956 | 0.40 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.87 | |||

| alpha-Pinene | 12.403 | 0.37 | 2.10 | 1.91 | 0.16 | 12.72 | 0.86 | 2.21 | |

| alpha-Fenchene | 13.199 | 0.01 | 0.10 | ||||||

| Camphene | 13.324 | 1.00 | 0.02 | 0.85 | 4.32 | 0.02 | |||

| Thuja-2,4(10)-diene | 13.494 | 0.01 | 0.06 | ||||||

| Methyl cyclohexanone | 13.921 | 0.05 | |||||||

| 5-Methyl furfural | 14.211 | 0.02 | |||||||

| Benzaldehyde | 14.337 | 0.57 | |||||||

| Sabinene | 14.551 | 0.22 | 0.84 | 0.05 | 0.51 | 0.50 | |||

| beta-Pinene | 14.885 | 0.83 | 0.57 | 0.01 | 4.46 | 0.98 | 0.66 | ||

| 1-Octen-3-ol | 15.010 | 0.04 | |||||||

| 3-Octanone | 15.274 | 0.07 | |||||||

| Myrcene | 15.476 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 1.51 | 1.77 | 0.77 | |||

| 6-Methyl-5-hepten-2-one | 15.573 | 0.00 | 0.98 | ||||||

| Dehydro-1,8-cineole | 16.063 | 0.01 | 0.03 | ||||||

| Mircene | 16.325 | 0.76 | |||||||

| Ethyl hexanoate | 16.388 | 0.00 | |||||||

| 3-Octanal | 16.389 | 0.39 | |||||||

| para-Mentha-1(7)8-diene | 16.405 | 0.03 | 0.07 | ||||||

| para-Mentha-1(7),8-diene | 16.440 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Hexenyl acetate | 16.460 | 0.01 | 0.02 | ||||||

| trans- Dehydroxy linalool oxide | 16.544 | 0.05 | |||||||

| alpha -Phellandrene | 16.557 | 0.20 | |||||||

| alpha-Phellandrene | 16.580 | 1.15 | 0.31 | 0.37 | |||||

| delta-3-Carene | 16.672 | 0.10 | 0.07 | ||||||

| n-Octanal | 16.692 | 0.04 | 0.07 | ||||||

| alpha-Terpinene | 17.215 | 0.14 | 0.60 | 0.12 | 9.66 | ||||

| alpha-Terpinolene | 17.518 | 1.06 | |||||||

| meta-Cymene | 17.684 | 0.03 | 0.31 | 0.73 | |||||

| para-Cymene | 17.770 | 2.71 | 0.47 | 1.13 | 0.25 | 1.95 | |||

| Limonene | 18.037 | 1.47 | 2.71 | 0.23 | 2.30 | 19.99 | 1.10 | ||

| beta-Phellandrene | 18.200 | 4.88 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.76 | ||||

| 1,8-Cineole | 18.278 | 0.49 | 80.60 | 45.54 | 2.12 | 5.62 | |||

| cis-beta-Ocimene | 18.676 | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0.05 | |||||

| 2-Heptyl acetate | 18.899 | 0.03 | |||||||

| Butyl 2-methyl butyrate | 19.018 | 0.03 | |||||||

| trans-beta-Ocimene | 19.059 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.02 | |

| Salicylaldehyde | 19.368 | 0.04 | |||||||

| gamma-Terpinene | 19.868 | 0.09 | 0.31 | 0.01 | 0.73 | 0.24 | 19.12 | ||

| Acetophenone | 20.767 | 0.05 | |||||||

| cis-Sabinene hydrate | 21.210 | 0.23 | |||||||

| 4-Nonanone | 21.317 | 1.09 | |||||||

| Terpinolene | 21.630 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.30 | 0.09 | 3.20 | ||

| cis-Linalool oxide (furanoid) | 21.679 | 0.03 | |||||||

| para-Cymenene | 22.016 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | ||||

| 2-Nonanone | 22.420 | 0.02 | |||||||

| Rosefuran | 22.648 | 0.09 | |||||||

| Linalool | 22.650 | 2.85 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.07 | 0.02 | |

| Methyl benzoate | 22.743 | 0.01 | |||||||

| trans-Linalool oxide (furanoid) | 22.760 | 0.02 | |||||||

| para-Cimenene | 23.034 | 0.02 | |||||||

| Perillene | 23.107 | 0.05 | |||||||

| 2-Methyl 3-methyl butyl butyrate | 23.168 | 0.12 | |||||||

| alpha-Pinene oxide | 23.718 | 0.10 | |||||||

| 2-Methyl-6-methylen-octa-1,7-diene-3-one | 23.903 | 0.01 | |||||||

| Isopentyl isovalerate | 24.075 | 0.02 | |||||||

| cis-para-Menth-2-en-1-ol | 24.420 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.14 | |||||

| 3-Octanol acetate | 24.466 | 0.10 | |||||||

| alpha-Campholenal | 24.547 | 0.03 | |||||||

| trans-para-Menth-2-en-1-ol | 25.718 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.04 | |||||

| Epiphotocitral A | 25.954 | 0.11 | |||||||

| 3-Methyl benzofuran | 26.020 | 0.01 | |||||||

| Camphor | 26.139 | 0.54 | 12.71 | ||||||

| exo-Isocitral | 26.262 | 0.12 | |||||||

| trans- beta- Terpineol | 26.528 | 0.02 | |||||||

| trans-Pinocarveol | 26.595 | 0.03 | |||||||

| trans-Chrysanthenol | 26.678 | 0.26 | |||||||

| Citronellal | 26.884 | 0.01 | 0.22 | ||||||

| trans-Pinocamphone | 26.888 | 0.04 | |||||||

| Pinocarvone | 27.013 | 0.03 | 0.05 | ||||||

| Menthone | 27.151 | 0.22 | |||||||

| 2-Benzenepropanal | 27.413 | 0.44 | |||||||

| Benzyl acetate | 27.417 | 0.03 | |||||||

| cis-Chrysanthenol | 27.526 | 0.99 | |||||||

| delta-Terpineol | 27.598 | 0.11 | 0.42 | ||||||

| Borneol | 27.729 | 0.13 | 0.80 | ||||||

| Isomenthone | 27.774 | 0.06 | |||||||

| Ethyl benzoate | 27.968 | 0.01 | |||||||

| cis-Pinocamphone | 27.997 | 0.04 | |||||||

| Rosefuran epoxide | 28.065 | 0.17 | |||||||

| 2-Methyl benzofuran | 28.255 | 0.03 | |||||||

| Terpinen-4-ol | 28.261 | 1.69 | 0.81 | 0.71 | 0.54 | 42.04 | |||

| Menthol | 28.685 | 1.29 | |||||||

| para-Mentha-1,5-dien-8-ol | 28.735 | 0.01 | |||||||

| trans-Isocitral | 28.855 | 1.54 | |||||||

| Cryptone | 29.109 | 0.14 | 0.09 | ||||||

| alpha-Terpineol | 29.327 | 0.86 | 6.94 | 0.14 | 2.26 | 0.26 | 2.47 | ||

| Methyl salicylate | 29.472 | 0.12 | |||||||

| 4-cis-Decenal | 29.540 | 0.03 | |||||||

| cis-Dihydro carvone | 30.128 | 1.99 | |||||||

| Verbenone | 30.130 | 0.02 | 0.09 | ||||||

| n-Decanal | 30.372 | 0.04 | 0.14 | ||||||

| trans-Dihydro carvone | 30.553 | 0.24 | |||||||

| cis-Cinnamaldehyde | 31.336 | 0.40 | |||||||

| Bornyl formate | 31.509 | 0.01 | |||||||

| trans-Cinnamaldehyde | 31.703 | 52.91 | |||||||

| trans-Carveol | 31.732 | 0.29 | |||||||

| cis-Carveol | 32.832 | 0.17 | |||||||

| Neral | 33.204 | 0.08 | 31.89 | ||||||

| Piperitone | 33.345 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.60 | 0.01 | ||||

| Chavicol | 33.562 | 0.19 | |||||||

| Methyl phenethyl ketone | 33.640 | 0.01 | |||||||

| Cumin aldehyde | 33.682 | 0.04 | |||||||

| Carvone | 33.750 | 0.02 | 59.13 | ||||||

| Carvotanacetone | 33.845 | 0.04 | |||||||

| Geraniol | 33.882 | 0.08 | 6.39 | ||||||

| cis-Carvone oxide | 34.598 | 0.05 | |||||||

| Isopiperitenone | 34.980 | 0.04 | |||||||

| Bornyl acetate | 35.278 | 0.03 | 0.90 | ||||||

| Geranial | 35.330 | 0.12 | 42.56 | ||||||

| trans-Carvone oxide | 35.451 | 0.05 | 0.09 | ||||||

| Phellandral | 36.105 | 0.01 | |||||||

| Safrole | 36.244 | 0.03 | |||||||

| Menthyl acetate | 36.275 | 0.16 | |||||||

| 2-Undecanone | 36.329 | 0.01 | |||||||

| gamma-Neoclovene | 36.536 | 0.06 | |||||||

| Dihydroedulan | 36.565 | 0.04 | |||||||

| Carvacrol | 36.681 | 0.04 | |||||||

| Geranyl formate | 36.901 | 0.04 | |||||||

| delta-Elemene | 38.389 | 0.05 | |||||||

| Methyl geranate | 38.443 | 0.04 | |||||||

| Dihydro carvyl acetate | 38.578 | 0.27 | |||||||

| alpha-Cubebene | 39.343 | 0.01 | 0.06 | ||||||

| 2,3-Pinanediol | 40.057 | 0.01 | |||||||

| Eugenol | 40.260 | 2.36 | 78.27 | ||||||

| alpha-Terpinyl acetate | 40.582 | 0.96 | |||||||

| alpha-Ylangene | 40.809 | 0.20 | 0.07 | ||||||

| cis-Carvyl acetate | 40.817 | 0.22 | |||||||

| Isodene | 40.936 | 0.06 | |||||||

| alpha-Copaene | 41.239 | 0.57 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.18 | ||

| Hydro cinnamyl acetate | 41.323 | 0.33 | |||||||

| neo-Caryophyllene | 41.409 | 0.02 | |||||||

| 2-epi-alpha-Funebrene | 42.170 | 0.62 | |||||||

| beta-Elemene | 42.177 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.03 | ||||

| Geranyl acetate | 42.207 | 0.02 | 4.38 | ||||||

| Methyl propenyl hexahydro benzofuran | 42.294 | 0.13 | |||||||

| alpha-Isocomene | 42.346 | 0.04 | |||||||

| Benzyl pentanoate | 42.420 | 0.03 | |||||||

| beta-Bourbonene | 42.465 | 1.66 | |||||||

| alpha-Duprezianene | 42.469 | 0.79 | |||||||

| 7-epi-Sesquithujene | 42.540 | 0.08 | |||||||

| alpha -Bourbonene | 42.649 | 0.14 | |||||||

| beta-Cubebene | 42.751 | 0.03 | |||||||

| Isolongifolene | 42.911 | 0.14 | |||||||

| Methyl eugenol | 42.953 | 0.01 | 0.03 | ||||||

| cis-Jasmone | 43.069 | 0.13 | |||||||

| cis-Caryophyllene | 43.104 | 0.01 | 0.02 | ||||||

| Vanillin | 43.147 | 0.05 | |||||||

| beta-Maaliene | 43.297 | 0.34 | |||||||

| beta-Longipinene | 43.397 | 0.19 | |||||||

| alpha-Funebrene | 43.525 | 0.21 | |||||||

| alpha-Gurjunene | 43.562 | 0.02 | |||||||

| di-epi-alpha-Cedrene | 43.728 | 0.10 | |||||||

| Aristolene | 44.055 | 0.03 | |||||||

| beta-Caryophyllene | 44.127 | 0.94 | 3.83 | 7.41 | 0.09 | 1.50 | 4.16 | 0.47 | |

| 2-epi-beta-Funberene | 44.340 | 0.44 | |||||||

| gamma-Maaliene | 44.582 | 0.06 | |||||||

| alpha-Cedrene | 44.648 | 29.92 | |||||||

| beta-Ylangene | 44.670 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.26 | |||||

| beta- Caryophyllene | 44.769 | 1.22 | |||||||

| beta-Copaene | 44.773 | 0.23 | 0.02 | ||||||

| beta-Duprezianene | 44.915 | 0.41 | |||||||

| alpha-Maaliene | 45.021 | 0.07 | |||||||

| beta- Cedrene | 45.046 | 5.59 | |||||||

| trans-Cinnamic acid | 45.120 | 0.13 | |||||||

| Aromadendrene | 45.247 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 1.07 | |||||

| Bourbon-1(1)-ene | 45.370 | 0.12 | |||||||

| alpha-Guaiene | 45.506 | 0.05 | |||||||

| Selina-5,11-diene | 45.765 | 0.12 | |||||||

| cis-Muurola-3,5-diene | 45.790 | 0.05 | |||||||

| cis-Thujopsene | 45.797 | 20.31 | |||||||

| Geranyl acetone | 45.868 | 0.02 | |||||||

| Spirolepechinene | 45.944 | 0.03 | 0.03 | ||||||

| trans-Muurola-3,5-diene | 45.959 | 0.14 | |||||||

| trans-beta-Farnesene | 46.123 | 0.02 | 0.66 | ||||||

| Isogermacrene D | 46.303 | 0.15 | |||||||

| alpha-Humulene | 46.339 | 0.77 | 0.92 | 0.17 | 0.43 | 0.06 | 0.08 | ||

| trans-Isoeugenol | 46.405 | 0.01 | 0.43 | ||||||

| trans-Cinnamyl acetate | 46.452 | 11.80 | |||||||

| Amorpha-4,11-diene | 46.470 | 0.02 | |||||||

| beta-Barbatene | 46.530 | 0.11 | |||||||

| trans-beta-Farmasene | 46.621 | 0.23 | |||||||

| Prezizaene | 46.640 | 0.11 | |||||||

| allo-Aromadendrene | 46.646 | 0.01 | 0.50 | ||||||

| 9-epi-trans- Caryophyllene | 47.169 | 0.10 | |||||||

| alpha-Acoradiene | 47.364 | 0.20 | |||||||

| cis-Cadina-1(6),4-diene | 47.391 | 0.39 | |||||||

| cis-Muurola-4(14),5-diene | 47.482 | 0.03 | |||||||

| beta-Acoradiene | 47.518 | 0.42 | |||||||

| trans-Cardina-1(6),4-diene | 47.530 | 0.12 | |||||||

| trans-Cadina-1(6),4-diene | 47.569 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.03 | |||||

| alpha-Amorphene | 47.791 | 0.01 | |||||||

| cis-Cardina-1(6),4-diene | 47.876 | 0.01 | |||||||

| 10-epi-beta-Acoradiene | 47.996 | 0.31 | |||||||

| trans-Cardina-1(6),4-diene | 48.061 | 0.03 | |||||||

| gamma-Curcumene | 48.197 | 0.09 | |||||||

| delta-Selinene | 48.325 | 0.12 | |||||||

| ar-Curcumene | 48.364 | 0.05 | |||||||

| beta-Selinene | 48.455 | 1.10 | 0.01 | 0.15 | |||||

| Viridiflorene | 48.571 | 0.90 | |||||||

| Germacrene D | 48.610 | 0.22 | 0.78 | ||||||

| trans-Muurola-4(14),5-diene | 48.620 | 0.03 | 0.12 | ||||||

| alpha-Selinene | 48.853 | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||||||

| Bicyclogermacrene | 48.868 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.94 | |||||

| alpha-Muurolene | 48.993 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.16 | |||||

| gamma-Amorphene | 49.154 | 0.01 | |||||||

| beta-Alaskene | 49.280 | 0.17 | |||||||

| beta-Bisabolene | 49.550 | 0.10 | |||||||

| epi-Cubebol | 49.602 | 0.07 | |||||||

| beta-Himachalene | 49.628 | 0.16 | |||||||

| alpha- Muurolene | 49.726 | 0.05 | |||||||

| trans- trans- alpha-Farnesene | 49.844 | 0.04 | |||||||

| alpha-Cuprenene | 49.880 | 2.10 | |||||||

| gamma-Cardinene | 49.886 | 0.08 | |||||||

| Pseudowiddrene | 49.920 | 1.05 | |||||||

| gamma-Cadinene | 49.930 | 1.17 | 0.02 | ||||||

| alpha-Chamigrene | 50.041 | 0.69 | |||||||

| delta-Cardinene | 50.167 | 0.05 | 0.31 | 0.16 | |||||

| Cuparene | 50.197 | 1.06 | |||||||

| delta-Cadinene | 50.230 | 0.02 | 1.20 | ||||||

| alpha-Alaskene | 50.250 | 0.23 | |||||||

| 1,2-Dihydro cuparene | 50.404 | 0.14 | |||||||

| gamma- Cadinene | 50.440 | 0.02 | |||||||

| Nootkatene | 50.470 | 0.02 | |||||||

| trans-Calamenene | 50.490 | 0.16 | |||||||

| Zonarene | 50.506 | 0.21 | |||||||

| Alaskene isomer | 50.726 | 0.34 | |||||||

| Eugenol acetate | 50.738 | 10.70 | |||||||

| Cubebol | 50.798 | 0.08 | |||||||

| Delta-Cardiene | 50.827 | 0.10 | |||||||

| trans- Calamenene | 50.957 | 0.02 | |||||||

| 1,4-Dihydro cuparene | 50.999 | 0.26 | |||||||

| trans-Cadine-1,4-diene | 51.092 | 0.20 | |||||||

| trans-gamma-Bisabolene | 51.176 | 0.09 | 0.14 | ||||||

| Clove Sesquiterpenoid 1 | 51.200 | 0.01 | |||||||

| Clove Sesquiterpenoid 2 | 51.242 | 0.05 | |||||||

| trans-ortho-Methoxy cinnamaldehyde | 51.343 | 0.45 | |||||||

| trans-Cadiene-1,4-diene | 51.587 | 0.00 | |||||||

| gamma- Cuprenene | 51.736 | 1.66 | |||||||

| alpha-Cardinene | 52.039 | 0.03 | |||||||

| Liguloxide | 52.143 | 0.20 | |||||||

| delta-Cuprenene | 52.491 | 0.31 | |||||||

| Clove Sesquiterpenoid 3 | 52.531 | 0.01 | |||||||

| 8-14-Cedranoxide | 52.560 | 0.07 | |||||||

| Isocaryophyllene oxide | 52.670 | 0.02 | |||||||

| Clove Sesquiterpenoid 4 | 52.987 | 0.14 | |||||||

| Geranyl butyrate | 53.149 | 0.15 | |||||||

| alpha-Elemol | 53.275 | 0.02 | |||||||

| Palustrol | 53.361 | 0.03 | |||||||

| Sesquirosefuran | 53.947 | 0.03 | |||||||

| Caryophyllene oxide | 54.011 | 1.24 | 0.49 | 0.03 | 0.45 | 0.07 | 0.05 | ||

| Clove Sesquiterpenoid 5 | 54.043 | 0.02 | |||||||

| Caryophyllene alcohol | 54.178 | 0.13 | 0.16 | ||||||

| Isocaryophyllene alcohol | 54.846 | 0.01 | |||||||

| Spathulenol | 54.993 | 0.02 | |||||||

| Viridiflorol | 55.420 | 0.07 | 0.10 | ||||||

| allo-Cedrol | 55.497 | 0.17 | |||||||

| Globulol | 55.527 | 0.02 | |||||||

| cis-Bisabol-11-ol | 55.556 | 0.01 | |||||||

| Humulene epoxide II | 56.108 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.03 | |||||

| Tetradecanal | 56.279 | 0.24 | |||||||

| Widdrol | 56.327 | 10.55 | |||||||

| Cedrol | 56.472 | 15.36 | |||||||

| 1-epi-Cubenol | 56.765 | 0.01 | 0.15 | ||||||

| Widdrol isomer | 56.913 | 0.05 | |||||||

| epi-Cedrol | 57.052 | 0.25 | |||||||

| 2-epi-alpha-Cedren-3-one | 57.434 | 0.10 | |||||||

| Cubenol | 57.539 | 0.10 | |||||||

| alpha-Acorenol | 57.785 | 0.10 | |||||||

| Clove Sesquiterpenoid 6 | 57.929 | 0.03 | |||||||

| gamma- Eudesmol | 58.206 | 0.02 | |||||||

| 3-Thujopsanone | 58.908 | 0.35 | |||||||

| Cedr-8-en-15-ol | 59.270 | 0.32 | |||||||

| beta-Eudesmol | 59.543 | 0.04 | |||||||

| epi-beta-Bisabolol | 59.571 | 0.09 | |||||||

| beta- Bisabolol | 59.641 | 0.08 | |||||||

| Acorenone | 60.072 | 0.06 | |||||||

| alpha-Bisabolol | 60.464 | 0.59 | |||||||

| iso-Thujopsanone | 60.969 | 0.15 | |||||||

| cis-Thujopsenal | 61.746 | 0.11 | |||||||

| trans-Thujopsenal | 62.133 | 0.11 | |||||||

| 4-Hydroxy-3-methoxy cinnamaldehyde | 62.802 | 0.06 | |||||||

| Benzyl benzoate | 64.849 | 0.67 | 0.04 | ||||||

| Nootkatone | 66.859 | 0.10 | |||||||

| Neophytadiene | 68.578 | 0.03 | |||||||

| Benzyl salicylate | 70.204 | 0.01 | |||||||

| Oleic Acid | 82.764 | 0.04 | |||||||

| Dehydrodieugenol | 97.894 | 0.25 | |||||||

| Dehydrodiisoeugenol | 98.655 | 0.18 |

References

- Bașer, K.H.C.; Buchbauer, G. Handbook of Essential Oils: Science, Technology, and Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; pp. 3–39. [Google Scholar]

- Iacob, F.; Ardelean, L.C.; Roi, A.; Tomoiaga, I.; Muntean, D.; Rusu, L.C. Assessment of the Antifungal Effect of Camellia sinensis Extracts on Candida albicans and Candida parapsilosis Strains—An in vitro Study. Pharmacogn. Res. 2025, 17, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S. Spiritual Practice and Essential Oil Therapy: Exploring the History and Individual Preferences Among Specific Plant Sources. Int. J. Aromather. 2003, 13, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, J.; Sureda, A.; Tenore, G.C.; Daglia, M.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Valussi, M.; Tundis, R.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Loizzo, M.R.; Ademiluyi, A.O.; et al. Biological Activities of Essential Oils: From Plant Chemoecology to Traditional Healing Systems. Molecules 2017, 22, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolouri, P.; Salami, R.; Kouhi, S.; Kordi, M.; Asgari Lajayer, B.; Hadian, J.; Astatkie, T. Applications of Essential Oils and Plant Extracts in Different Industries. Molecules 2022, 27, 8999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J. Chemical Composition of Essential Oils and Their Potential Applications in Postharvest Storage of Cereal Grains. Molecules 2025, 30, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masyita, A.; Mustika Sari, R.; Dwi Astuti, A.; Yasir, B.; Rahma Rumata, N.; Emran, T.B.; Nainu, F.; Simal-Gandara, J. Terpenes and Terpenoids as Main Bioactive Compounds of Essential Oils, their Roles in Human Health and Potential Application as Natural Food Preservatives. Food Chem. X 2022, 19, 100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokou, J.B.H.; Dongmo, P.M.J.; Boyom, F.F. Essential Oil’s Chemical Composition and Pharmacological Properties. In Essential Oils-Oils of Nature; El-Shemy, H.A., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, T.; Khan, M.U.; Sharma, V.; Gupta, K. Terpenoids in Essential Oils: Chemistry, Classification, and Potential Impact on Human Health and Industry. Phytomed. Plus 2024, 4, 100549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirković, S.; Martinović, M.; Tadić, V.M.; Nešić, I.; Jovanović, A.S.; Žugić, A. Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activity of Essential Oils from Selected Pinus Species from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.A.R.; Silva, L.P.; Ferreira, O.; Schröder, B.; Coutinho, J.A.P.; Pinho, S.P. Terpenes Solubility in Water and their Environmental Distribution. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 241, 996–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dippong, T.; Senila, L.; Muresan, L.E. Preparation and Characterization of the Composition of Volatile Compounds, Fatty Acids and Thermal Behavior of Paprika. Foods 2023, 12, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, R.; Sun, J.; Bo, Y.; Khattak, W.A.; Khan, A.A.; Jin, C.; Zeb, U.; Ullah, N.; Abbas, A.; Liu, W.; et al. Understanding the Influence of Secondary Metabolites in Plant Invasion Strategies: A Comprehensive Review. Plants 2024, 13, 3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminski, K.P.; Hoeng, J.; Lach-Falcone, K.; Goffman, F.; Schlage, W.K.; Latino, D. Exploring Aroma and Flavor Diversity in Cannabis sativa L.—A Review of Scientific Developments and Applications. Molecules 2025, 30, 2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, D.P.; Damasceno, R.O.S.; Amorati, R.; Elshabrawy, H.A.; de Castro, R.D.; Bezerra, D.P.; Nunes, V.R.V.; Gomes, R.C.; Lima, T.C. Essential Oils: Chemistry and Pharmacological Activities. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valarezo, E.; Vullien, A.; Conde-Rojas, D. Variability of the Chemical Composition of the Essential Oil from the Amazonian Ishpingo Species (Ocotea quixos). Molecules 2021, 26, 3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Miri, Y. Essential Oils: Chemical Composition and Diverse Biological Activities: A Comprehensive Review. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2025, 20, 101177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Nabi, M.H.; Ahmed, M.M.; Mia, M.S.; Islam, S.; Zzaman, W. Essential oils: Advances in extraction techniques, chemical composition, bioactivities, and emerging applications. Food Chem. Adv. 2025, 8, 101048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongnuanchan, P.; Benjakul, S. Essential oils: Extraction, Bioactivities, and their Uses for Food Preservation. J. Food Sci. 2014, 79, R1231–R1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikmoradi, A.; Khaleghverdi, M.; Seddighi, I.; Moradkhani, S.; Soltanian, A.; Cheraghi, F. Effect of Inhalation Aromatherapy with Lavender Essence on Pain Associated with Intravenous Catheter Insertion in Preschool Children: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2017, 28, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboubi, M. Mentha spicata as Natural Analgesia for Treatment of Pain in Osteoarthritis Patients. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2017, 26, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltani, R.; Soheilipour, S.; Hajhashemi, V.; Asghari, G.; Bagheri, M.; Molavi, M. Evaluation of the Effect of Aromatherapy with Lavender Essential Oil on Post-Tonsillectomy Pain in Pediatric Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2013, 77, 1579–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexa, E.; Sumalan, R.M.; Danciu, C.; Obistioiu, D.; Negrea, M.; Poiana, M.-A.; Rus, C.; Radulov, I.; Pop, G.; Dehelean, C. Synergistic Antifungal, Allelopathic and Anti-Proliferative Potential of Salvia officinalis L. and Thymus vulgaris L. Essential Oils. Molecules 2018, 23, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vora, L.K.; Gholap, A.D.; Hatvate, N.T.; Naren, P.; Khan, S.; Chavda, V.P.; Balar, P.C.; Gandhi, J.; Khatri, D.K. Essential Oils for Clinical Aromatherapy: A Comprehensive Review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 330, 118180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Gallardo, K.; Quintero-Rincón, P.; Olivero-Verbel, J. Aromatherapy and Essential Oils: Holistic Strategies in Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Integral Wellbeing. Plants 2025, 14, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Chen, X.; Chu, C.H.; Yu, O.Y.; He, J.; Li, M. Roles of Streptococcus mutans in Human Health: Beyond Dental Caries. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1503657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, R.; Otsugu, M.; Hamada, M.; Matayoshi, S.; Teramoto, N.; Iwashita, N.; Naka, S.; Matsumoto-Nakano, M.; Nakano, K. Potential Involvement of Streptococcus mutans Possessing Collagen Binding Protein Cnm in Infective Endocarditis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Li, Y. From Teeth to Body: The Complex Role of Streptococcus mutans in Systemic Diseases. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2025, 40, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gloria-Garza, M.A.; Reyna-Martínez, G.R.; Jiménez-Salas, Z.; Campos-Góngora, E.; Kačániová, M.; Aguirre-Cavazos, D.E.; Bautista-Villarreal, M.; Leos-Rivas, C.; Elizondo-Luevano, J.H. Medicinal Plants Against Dental Caries: Research and Application of Their Antibacterial Properties. Plants 2025, 14, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shami, I.Z.; Al-Hamzi, M.A.; Al-Shamahy, H.A.; Majeed, A.L.A.A. Efficacy of Some Antibiotics Against Streptococcus mutans Associated with Tooth Decay in Children and their Mothers. J. Dent. Oral Health 2019, 2, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Zeng, Y.; Zhao, X.; Washio, J.; Takahashi, N.; Zhang, L. Investigation of Drug Resistance of Caries-Related Streptococci to Antimicrobial Peptide GH12. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 991938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacopetta, D.; Ceramella, J.; Catalano, A.; D’Amato, A.; Lauria, G.; Saturnino, C.; Andreu, I.; Longo, P.; Sinicropi, M.S. Diarylureas: New Promising Small Molecules against Streptococcus mutans for the Treatment of Dental Caries. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soliman, S.S.M.; Alsaadi, A.I.; Youssef, E.G.; Khitrov, G.; Noreddin, A.M.; Husseiny, M.I.; Ibrahim, A.S. Calli Essential Oils Synergize with Lawsone Against Multidrug Resistant Pathogens. Molecules 2017, 22, 2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, T.; Os, A. Plant Essential Oil: An Alternative to Emerging Multidrug Resistant Pathogens. J. Microbiol. Exp. 2017, 5, 00163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, A.; Iacopetta, D.; Pellegrino, M.; Aquaro, S.; Franchini, C.; Sinicropi, M.S. Diarylureas: Repositioning from Antitumor to Antimicrobials or Multi-Target Agents against New Pandemics. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahador, A.; Lesan, S.; Kashi, N. Effect of Xylitol on Cariogenic and Beneficial Oral Streptococci: A Randomized, Double-Blind Crossover Trial. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2012, 4, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Haghgoo, R.; Afshari, E.; Ghanaat, T.; Aghazadeh, S. Comparing the Efficacy of Xylitol-containing and Conventional Chewing Gums in Reducing Salivary Counts of Streptococcus mutans: An in vivo Study. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2015, 5, S112–S117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, I.; Kaur, P.; Kaushal, U.; Kaur, V.; Shekhar, N. Essential Oils in Treatment and Management of Dental Diseases. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2022, 12, 7267–7286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagli, N.; Dagli, R.; Mahmoud, R.S.; Baroudi, K. Essential Oils, their Therapeutic Properties, and Implication in Dentistry: A Review. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2015, 5, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, B.R.; Ramesh, N.; Rupal, S.; Roopesh, T. An in vitro Study on the Anti-Microbial Efficacy of Ten Herbal Extracts on Primary Plaque Colonizers. J. Young Pharm. 2014, 6, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, C.-M.; Radu, C.C.; Bochiș, S.-A.; Arbănași, E.M.; Lucan, A.I.; Murvai, V.R.; Zaha, D.C. Revisiting the Therapeutic Effects of Essential Oils on the Oral Microbiome. Pharmacy 2023, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulitovsky, S.B.; Kalinina, O.V.; Pankratieva, L.I. Effectiveness Evaluation of Toothpaste Based on the Cedar Essential Oil for Preventing True Oral Pathologic Halitosis. Sci. Notes Pavlov. St. Petersburg State Med. Univ. 2018, 24, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Doterra.com. Available online: https://www.doterra.com/US/en/cptg-testing-process (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Available online: https://www.eucast.org (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. CLSI Supplement M100, 35th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Berwyn, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 304–306. Available online: https://clsi.org/shop/standards/m100 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- doTERRA Source to You. Available online: https://www.sourcetoyou.com/en (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- El-Tarabily, K.A.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Alagawany, M.; Arif, M.; Batiha, G.E.; Khafaga, A.F.; Elwan, H.A.M.; Elnesr, S.S.; Abd El-Hack, E.M. Using Essential Oils to Overcome Bacterial Biofilm Formation and Their Antimicrobial Resistance. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 5145–5156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khwaza, V.; Aderibigbe, B.A. Antibacterial Activity of Selected Essential Oil Components and Their Derivatives: A Review. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atazhanova, G.A.; Levaya, Y.K.; Badekova, K.Z.; Ishmuratova, M.Y.; Smagulov, M.K.; Ospanova, Z.O.; Smagulova, E.M. Inhibition of the Biofilm Formation of Plant Streptococcus mutans. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wińska, K.; Mączka, W.; Łyczko, J.; Grabarczyk, M.; Czubaszek, A.; Szumny, A. Essential Oils as Antimicrobial Agents—Myth or Real Alternative? Molecules 2019, 24, 2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freires, I.A.; Denny, C.; Benso, B.; De Alencar, S.M.; Rosalen, P.L. Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oils and Their Isolated Constituents against Cariogenic Bacteria: A Systematic Review. Molecules 2015, 20, 7329–7358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, L.K.; Jawale, B.A.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, H.; Kumar, C.D.; Kulkarni, P.A. Antimicrobial Activity of Commercially Available Essential Oils Against Streptococcus mutans. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2012, 13, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Yoon, H. Antimicrobial activity of essential oil against oral strain. Int. J. Clin. Prev. Dent. 2018, 14, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexa, V.T.; Galuscan, A.; Popescu, I.; Tirziu, E.; Obistioiu, D.; Floare, A.D.; Perdiou, A.; Jumanca, D. Synergistic/Antagonistic Potential of Natural Preparations Based on Essential Oils Against Streptococcus mutans from the Oral Cavity. Molecules 2019, 24, 4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, D.G.; Sganzerla, W.G.; da Silva, L.R.; Vieira, Y.G.S.; Almeida, A.R.; Dominguini, D.; Ceretta, L.; Pinheiro, A.C.; Bertoldi, F.C.; Becker, D.; et al. Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Potential of Eucalyptus Essential Oil-Based Nanoemulsions for Mouthwashes Application. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Carvalho, I.; Purgato, G.A.; Píccolo, M.S.; Pizziolo, V.R.; Coelho, R.R.; Díaz-Muñoz, G.; Nogueira Díaz, M.A. In vitro Anticariogenic and Antibiofilm Activities of Toothpastes Formulated with Essential Oils. Arch. Oral Biol. 2020, 117, 104834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga, A.S.; de Melo Simas, L.L.; Pires, J.G.; Souza, B.M.; de Souza Rosa de Melo, F.P.; Saldanha, L.L.; Dokkedal, A.L.; Magalhães, A.C. Antibiofilm and Anti-Caries Effects of an Experimental Mouth Rinse Containing Matricaria chamomilla L. Extract Under Microcosm Biofilm on Enamel. J. Dent. 2020, 99, 103415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, D.; Chen, B.; Li, Y.; Pang, X.; Fu, Q.; Xiao, Z.; Shi, Z.; Li, X.; Luo, C.; Zhou, Z.-K.; et al. Au@Ag Nanorods-PDMS Wearable Mouthguard as a Visualized Detection Platform for Screening Dental Caries and Periodontal Diseases. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2022, 11, e2102682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snoussi, M.; Noumi, E.; Trabelsi, N.; Flamini, G.; Papetti, A.; De Feo, V. Mentha spicata Essential Oil: Chemical Composition, Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities Against Planktonic and Biofilm Cultures of Vibrio spp. Strains. Molecules 2015, 20, 14402–14424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, K.K.; Khanuja, S.P.S.; Ahmad, A.; Gupta, V.K.; Kumar, S. Antimicrobial Activity Profiles of the Two Enantiomers of Limonene and Carvone Isolated from the Oils of Mentha Spicata and Anethum Sowa. Flavour Fragr. J. 2002, 17, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landeo-Villanueva, G.E.; Salazar-Salvatierra, M.E.; Ruiz-Quiroz, J.R.; Zuta-Arriola, N.; Jarama-Soto, B.; Herrera-Calderon, O.; Pari-Olarte, J.B.; Loyola-Gonzales, E. Inhibitory Activity of Essential Oils of Mentha spicata and Eucalyptus globulus on Biofilms of Streptococcus mutans in an in vitro Model. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiekh, R.A.E.; Atwa, A.M.; Elgindy, A.M.; Mustafa, A.M.; Senna, M.M.; Alkabbani, M.A.; Ibrahim, K.M. Therapeutic applications of eucalyptus essential oils. Inflammopharmacology 2025, 33, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čmiková, N.; Galovičová, L.; Schwarzová, M.; Vukic, M.D.; Vukovic, N.L.; Kowalczewski, P.Ł.; Bakay, L.; Kluz, M.I.; Puchalski, C.; Kačániová, M. Chemical Composition and Biological Activities of Eucalyptus globulus Essential Oil. Plants 2023, 12, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mączka, W.; Duda-Madej, A.; Górny, A.; Grabarczyk, M.; Wińska, K. Can Eucalyptol Replace Antibiotics? Molecules 2021, 26, 4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldbeck, J.C.; do Nascimento, J.E.; Jacob, R.G.; Fiorentini, Â.M.; da Silva, W.P. Bioactivity of Essential Oils from Eucalyptus Globulus and Eucalyptus Urograndis against Planktonic Cells and Biofilms of Streptococcus mutans. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 60, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, A.; Costantini, S.; De Angelis, M.; Garzoli, S.; Božović, M.; Mascellino, M.T.; Vullo, V.; Ragno, R. High Potency of Melaleuca alternifolia Essential Oil Against Multi-Drug Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria and Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Molecules 2018, 23, 2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brun, P.; Bernabè, G.; Filippini, R.; Piovan, A. In Vitro Antimicrobial Activities of Commercially Available Tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia) Essential Oils. Curr. Microbiol. 2019, 76, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.-M.; Zhou, H.-Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Mei, Y.-F. In Vitro Evaluation of the Antibacterial Properties of Tea Tree Oil on Planktonic and Biofilm-Forming Streptococcus mutans. AAPS PharmSciTech 2020, 21, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Park, O.B.; An, H.R.; Yu, Y.H.; Hong, E.B.; Kang, K.H.; Koong, H.S. Antibacterial Effects of Tea Tree Oil and Mastic Oil to Streptococcus mutans. J. Dent. Hyg. Sci. 2023, 23, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiatrak, K.; Morawiec, T.; Rój, R.; Kownacki, P.; Nitecka-Buchta, A.; Niedzielski, D.; Wychowański, P.; Machorowska-Pieniążek, A.; Cholewka, A.; Baldi, D.; et al. Evaluation of Effectiveness of a Toothpaste Containing Tea Tree Oil and Ethanolic Extract of Propolis on the Improvement of Oral Health in Patients Using Removable Partial Dentures. Molecules 2021, 26, 4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahapatra, A.; Panda, S.; Tumedei, M.; Panda, S.; Das, A.C.; Kumar, M.; Del Fabbro, M. Clinical and Microbiological Evaluation of 0.2% Tea tree Oil Mouthwash in Prevention of Dental Biofilm-Induced Gingivitis. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriamah, N.; Lessang, R.; Kemal, Y. Effectiveness of Toothpaste Containing Propolis, Tea Tree Oil, and Sodium Monofluorophosphate Against Plaque and Gingivitis. Int. J. Appl. Pharm. 2019, 11, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatori, C.; Barchi, L.; Guzzo, F.; Gargari, M. A Comparative Study of Antibacterial and Anti-inflammatory Effects of Mouthrinse Containing Tea Tree Oil. Oral Implantol. 2017, 10, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.; Mostafa, M.; El-Araby, S.; El-Bouseary, M. Evaluation of the Effect of Tea tree oil Mouthwash on Streptococcus mutans as Compared with Chlorhexidine in a Group of Egyptian Children. Al-Azhar J. Dent. 2023, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, N.P.; Tandon, S.; Nayak, R.; Naidu, S.; Anand, P.S.; Kamath, Y.S. The effect of aloe vera and tea tree oil mouthwashes on the oral health of school children. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2020, 21, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, A.N.; Byatappa, V.; Raju, R.; Umakanth, R.; Alayadan, P. Antiplaque and Antigingivitis Effectiveness of Tea tree Oil and Chlorine Dioxide Mouthwashes Among Young Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. World J. Dent. 2020, 11, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casarin, M.; Pazinatto, J.; Oliveira, L.M.; Souza, M.E.; Santos, R.C.V.; Zanatta, F.B. Anti-biofilm and Anti-inflammatory Effect of a Herbal Nanoparticle Mouthwash: A Randomized Crossover Trial. Braz. Oral Res. 2019, 33, e062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manvitha, K.; Bidya, B. Review on pharmacological activity of Cymbopogon citratus. Int. J. Herb. Med. 2014, 1, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mukarram, M.; Choudhary, S.; Khan, M.A.; Poltronieri, P.; Khan, M.M.A.; Ali, J.; Kurjak, D.; Shahid, M. Lemongrass Essential Oil Components with Antimicrobial and Anticancer Activities. Antioxidants 2021, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helal, G.A.; Sarhan, M.M.; Abu Shahla, A.N.K.; Abou El-Khair, E.K. Effects of Cymbopogon citratus L. Essential Oil on the Growth, Morphogenesis and Aflatoxin Production of Aspergillus flavus ML2-strain. J. Basic Microbiol. 2007, 47, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrakul, K.; Srisatjaluk, R.; Srisukh, V.; Lomarat, P.; Vongsawan, K.; Kosanwat, T. Cymbopogon Citratus (Lemongrass Oil) Oral Sprays as Inhibitors of Mutans Streptococci Biofilm Formation. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2018, 12, ZC06–ZC12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofiño-Rivera, A.; Ortega-Cuadros, M.; Galvis-Pareja, D.; Jiménez-Rios, H.; Merini, L.J.; Martínez-Pabón, M.C. Effect of Lippia alba and Cymbopogon citratus Essential Oils on Biofilms of Streptococcus mutans and Cytotoxicity in CHO cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 194, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.A.C.; Borges, A.C.; Brighenti, F.L.; Salvador, M.J.; Gontijo, A.V.L.; Koga-Ito, C.Y. Cymbopogon citratus Essential Oil: Effect on Polymicrobial Caries-Related Biofilm with Low Cytotoxicity. Braz. Oral Res. 2017, 31, e89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rego, C.B.; Silva, A.M.; Gonslves, L.M.; Paschoal, M.A. In vitro Antimicrobial Activity of Essential Oil of Cymbopogon citratus (lemongrass) on Streptococcus mutans Biofilm. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2016, 10, 1224–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouta, L.F.G.L.; Marques, R.S.; Koga-Ito, C.Y.; Salvador, M.J.; Giro, E.M.A.; Brighenti, F.L. Cymbopogon citratus Essential Oil Increases the Effect of Digluconate Chlorhexidine on Microcosm Biofilms. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Jiang, X.; Tian, Y.; Yan, S.; Liu, J.; Xie, J.; Zhang, F.; Yao, C.; Hao, E. Therapeutic Potential of Cinnamon Oil: Chemical Composition, Pharmacological Actions, and Applications. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, W.G. Antibacterial and Antifungal Effect of Cinnamon. Microbiol. Res. J. Int. 2018, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabavi, S.F.; Di Lorenzo, A.; Izadi, M.; Sobarzo-Sánchez, E.; Daglia, M.; Nabavi, S.M. Antibacterial Effects of Cinnamon: From Farm to Food, Cosmetic and Pharmaceutical Industries. Nutrients 2015, 7, 7729–7748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touati, A.; Mairi, A.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Idres, T. Essential Oils for Biofilm Control: Mechanisms, Synergies, and Translational Challenges in the Era of Antimicrobial Resistance. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atisakul, K.; Saewan, N. The Antibacterial Potential of Essential Oils of Oral Care Thai Herbs against Streptococcus mutans and Solobacterium moorei—In Vitro Approach. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiwattanarattanabut, K.; Choonharuangdej, S.; Srithavaj, T. In vitro Anti-Cariogenic Plaque Effects of Essential Oils Extracted from Culinary Herbs. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, DC30–DC35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanakiev, S. Effects of Cinnamon (Cinnamomum spp.) in Dentistry: A Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, V.K.; Srivastava, S.; Ashish; Dash, K.K.; Singh, R.; Darl, A.H.; Singh, T.; Farooqui, A.; Shaikh, A.M.; Kovacs, B. Bioactive Properties of Clove (Syzygium aromaticum) Essential Oil Nanoemulsion: A Comprehensive Review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e22437–e22553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafri, H.; Ahmad, I. In Vitro Efficacy of Clove Oil and Eugenol against Staphylococcus spp. and Streptococcus mutans on Hydrophobicity, Hemolysin Production and Biofilms and their Synergy with Antibiotics. Adv. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marya, C.M.; Satija, G.; Avinash, J.; Nagpal, R.; Kapoor, R.; Ahmad, A. In vitro Inhibitory Effect of Clove Essential Oil and its Two Active Principles on Tooth Decalcification by Apple Juice. Int. J. Dent. 2012, 2012, 759618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatene, N.; Mounaji, K.; Soukri, A. Effect of Eugenol on Streptococcus mutans Adhesion on NiTi Orthodontic Wires: In Vitro and In Vivo Conditions. Eur. J. Gen. Dent. 2021, 10, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evary, Y.M.; Djide, N.J.N.; Aulia, I.N. Discovery of Active Antibacterial Fractions of Different Plant Part Extracts of Clove (Syzigium aromaticum) against Streptoccus mutans. JEBAS 2024, 12, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirpour, M.; Gholizadeh Siahmazgi, Z.; Sharifi Kiasaraie, M. Antibacterial Activity of Clove, Gall Nut Methanolic and Ethanolic Extracts on Streptococcus mutans PTCC 1683 and Streptococcus salivarius PTCC 1448. J. Oral Biol. Craniofacial Res. 2015, 5, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.S.; Li, Y.; Cao, X.; Cui, Y. The Effect of Eugenol on the Cariogenic Properties of Streptococcus mutans and Dental Caries Development in Rats. Exp. Ther. Med. 2013, 5, 1667–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemzadeh Rahbardar, M.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Therapeutic Effects of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) and its Active Constituents on Nervous System Disorders. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2020, 23, 1100–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, A.; Ali, A.; Abdullah, H.M.; Balaji, J.; Kaur, J.; Saeed, F.; Wasiq, M.; Imran, A.; Jibraeel, H.; Raheem, M.S.; et al. Nutritional Composition, Phytochemical Profile, Therapeutic Potentials, and Food Applications of Rosemary: A Comprehensive Review. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 135, 106688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Macedo, L.M.; Santos, É.M.D.; Militão, L.; Tundisi, L.L.; Ataide, J.A.; Souto, E.B.; Mazzola, P.G. Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L., syn. Salvia rosmarinus Spenn.) and Its Topical Applications: A Review. Plants 2020, 9, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, E.; Batool, R.; Akhtar, W.; Shahzad, T.; Malik, A.; Shah, M.A.; Iqbal, S.; Rauf, A.; Zengin, G.; Bouyahya, A.; et al. Rosemary Species: A Review of Phytochemicals, Bioactivities and Industrial Applications. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 151, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucia, M.; Wietrak, E.; Szymczak, M.; Kowalczyk, P. Effect of Ligilactobacillus salivarius and Other Natural Components against Anaerobic Periodontal Bacteria. Molecules 2020, 25, 4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yea, J.; Yoo, H.; Yu, H. Effect of Rosemary Extract on Early Biofilm of Streptococcus mutans. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2024, 20, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valones, M.A.A.; Silva, I.C.G.; Gueiros, L.A.M.; Leo, J.C.; Caldas, A.F.; Carvalho, A.A.T. Clinical Assessment of Rosemary based Toothpaste (Rosmarinus officinalis Linn.): A Randomized Controlled Double-Blind Study. Braz. Dent. J. 2019, 30, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Yao, L. The Anxiolytic Effect of Juniperus virginiana L. Essential Oil and Determination of Its Active Constituents. Physiol. Behav. 2018, 189, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korona-Glowniak, I.; Glowniak-Lipa, A.; Ludwiczuk, A.; Baj, T.; Malm, A. The In Vitro Activity of Essential Oils against Helicobacter Pylori Growth and Urease Activity. Molecules 2020, 25, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Kim, Y.M.; Lee, H.S. Growth-inhibiting Effects of Juniperus virginiana Leaf-Extracted Components towards Human Intestinal Bacteria. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2005, 14, 164–167. [Google Scholar]

- Heydari, M.; Rauf, A.; Thiruvengadam, M.; Chen, X.; Hashempur, M.H. Editorial: Clinical Safety of Natural Products, an Evidence-Based Approach. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 960556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.A.; Harnett, J.E.; Cairns, R. Essential Oil Exposures in Australia: Analysis of Cases Reported to the NSW Poisons Information Centre. Med. J. Aust. 2020, 212, 132–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suresh, D.; VijayaKumar, S.; Pradhan, P.; Balasubramanian, S. Fatal Eucalyptus Oil Poisoning in an Adult Male: A case report with comprehensive autopsy and histopathological findings. Cureus 2025, 17, e83053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, K.A.; Carson, C.F.; Riley, T.V.; Nielsen, J.B. A Review of the Toxicity of Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree) oil. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2006, 44, 616–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoja, I.; Daskalaki, Z.; Lobanova, L.; Said, R.S.; Cooper, D.M.L.; Arapostathis, K.; Katselis, G.S.; Papagerakis, S.; Papagerakis, P. Tea tree OIL in Inhibiting Oral Cariogenic Bacterial Growth an In Vivo Study for Managing Dental Caries. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairey, L.; Agnew, T.; Bowles, E.J.; Barkla, B.J.; Wardle, J.; Lauche, R. Efficacy and Safety of Melaleuca alternifolia (Tea tree) Oil for Human Health—A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1116077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catlin, N.R.; Herbert, R.; Janardhan, K.; Hejtmancik, M.R.; Fomby, L.M.; Vallant, M.; Kissling, G.E.; DeVito, M.J. Dose-Response Assessment of the Dermal Toxicity of Virginia cedarwood oil in F344/N Rats and B6C3F1/N mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2016, 98, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- El Menyiy, N.; Mrabti, H.N.; El Omari, N.; Bakili, A.E.; Bakrim, S.; Mekkaoui, M.; Balahbib, A.; Amiri-Ardekani, E.; Ullah, R.; Alqahtani, A.S.; et al. Medicinal Uses, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, and Toxicology of Mentha spicata. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 7990508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesinghe, G.K.; de Oliveira, T.R.; Maia, F.C.; de Feiria, S.N.B.; Barbosa, J.P.; Joia, F.; Boni, G.C.; Höfling, J.F. Efficacy of True Cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum) Leaf Essential Oil as a Therapeutic Alternative for Candida Biofilm Infections. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2021, 24, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemzadeh Rahbardar, M.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Toxicity and Safety of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis): A Comprehensive Review. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusuma, I.Y.; Perdana, M.I.; Vágvölgyi, C.; Csupor, D.; Takó, M. Exploring the Clinical Applications of Lemongrass Essential Oil: A Scoping Review. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aksoylu Özbek, Z.; Günç Ergönül, P. Clove (Syzygium aromaticum) and Eugenol Toxicity. In Clove (Syzygium aromaticum); Ramadan, M.F., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 267–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neagu, R.; Popovici, V.; Ionescu, L.E.; Ordeanu, V.; Popescu, D.M.; Ozon, E.A.; Gîrd, C.E. Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Effects of Different Samples of Five Commercially Available Essential Oils. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agatonovic-Kustrin, S.; Ristivojevic, P.; Gegechkori, V.; Litvinova, T.M.; Morton, D.W. Essential Oil Quality and Purity Evaluation via FT-IR Spectroscopy and Pattern Recognition Techniques. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| EO Common Name | Botanical Name | Botanical Family | Extracted From | Batch Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cinnamon | Cinnamomum verum | Lauraceae | bark, leaves, fruits, flowers | 232472 |

| Tea tree | Melaleuca alternifolia | Myrtaceae | leaves, terminal branches | 233113 |

| Spearmint | Mentha spicata | Lamiaceae | leaves, stems, flowering tops | 231733 |

| Rosemary | Rosmarinus officinalis | Labiatae | leaves, flower buds, stems | 233382 |

| Clove | Eugenia caryophyllata | Myrtaceae | dried flower buds, leaves, stems | 231882 |

| Eucalyptus | Eucalyptus radiata | Myrtaceae | wood, leaves, roots, flowers, fruits | 2331911 |

| Cedarwood | Juniperus virginiana | Cupressaceae | wood chips, sawdust | 240121 |

| Lemongrass | Cymbopogon flexuosus | Poaceae | leaves, flowering tops | 233101 |

| EO | Mean IZ Diameter (mm) | Susceptibility Classification |

|---|---|---|

| Spearmint | 41.33 | susceptible |

| Eucalyptus | 39.33 | susceptible |

| Tea tree | 32.11 | susceptible |

| Lemongrass | 31.00 | susceptible |

| Cinnamon | 26.33 | susceptible |

| Clove | 24.89 | susceptible |

| Rosemary | 24.78 | susceptible |

| Cedarwood | 23.56 | susceptible |

| EO | Mean MIC (μg/mL) | Mean MBC (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| Spearmint | 10 | 20 |

| Eucalyptus | 20 | 20 |

| Tea tree | 20 | 40 |

| Lemongrass | 20 | 40 |

| Cinnamon | 40 | 40 |

| Clove | 40 | 40 |

| Rosemary | 40 | 40 |

| Cedarwood | 40 | 40 |

| Groups | Spearmint | Eucalyptus | Tea Tree | Lemongrass | Cinnamon | Clove | Rosemary | Cedarwood |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Minimum | 38 | 37 | 30 | 29 | 25 | 22 | 22 | 22 |

| Maximum | 44 | 42 | 35 | 33 | 29 | 26 | 28 | 25 |

| Mean () | 41.33 | 39.33 | 32.11 | 31 | 26.33 | 24.88 | 24.77 | 23.55 |

| Mean Confidence Interval (95% CI) | [39.94, 42.71] | [38.11, 40.54] | [30.81, 33.41] | [29.91, 32.08] | [25.31, 27.35] | [23.91, 25.86] | [23.40, 26.15] | [22.77, 24.33] |

| Standard Deviation (S) | 1.8028 | 1.5811 | 1.6915 | 1.4142 | 1.3229 | 1.2693 | 1.7873 | 1.0138 |

| SD Confidence Interval | [1.21, 3.45] | [1.06, 3.02] | [1.14, 3.24] | [0.95, 2.70] | [0.89, 2.53] | [0.85, 2.43] | [1.20, 3.42] | [0.68, 1.94] |

| Variance (S2) | 3.25 | 2.5 | 2.86 | 2 | 1.75 | 1.61 | 3.19 | 1.02 |

| Standard Deviation (σ) | 1.69 | 1.49 | 1.59 | 1.33 | 1.24 | 1.19 | 1.68 | 0.95 |

| Variance (σ2) | 2.88 | 2.22 | 2.54 | 1.77 | 1.55 | 1.43 | 2.83 | 0.91 |

| Q1 | 40 | 38 | 31 | 30 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 23 |

| Median | 42 | 39 | 32 | 31 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 24 |

| Q3 | 42 | 40 | 33 | 32 | 27 | 26 | 26 | 24 |

| Interquartile range | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| SW p-value (W) | 0.86 | 0.95 | 0.62 | 0.34 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.98 | 0.05 |

| KS p-value (D) | 0.37 | 0.88 | 0.43 | 0.34 | 0.40 | 0.01 | 0.90 | 0.004 |

| EO | Dominant Constituent | RT (min) | Relative Abundance (%) | Shannon Index (H′) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clove | Eugenol | 40.26 | 78.27 | 0.85 |

| Cinnamon | trans-Cinnamaldehyde | 31.70 | 52.91 | 0.95 |

| Eucalyptus | 1,8-Cineole | 18.28 | 80.60 | 1.12 |

| Spearmint | Carvone | 33.75 | 59.13 | 1.45 |

| Lemongrass | Geranial | 35.33 | 42.56 | 1.38 |

| Tea Tree | Terpinen-4-ol | 28.26 | 42.04 | 1.50 |

| Rosemary | Camphor | 26.13 | 12.71 | 1.72 |

| Cedarwood | Cedrol | 56.47 | 15.36 | 1.61 |

| Variable | Description | ρ (Spearman) | p-Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shannon diversity index (H′) | Chemical diversity across all detected constituents | −0.26 | 0.53 | Weak negative; higher diversity → lower activity |

| Carvone (%) | Major constituent in Spearmint oil | +0.58 | 0.09 | Moderate positive; higher content linked to stronger inhibition |

| 1,8-Cineole (%) | Dominant constituent in Eucalyptus and Rosemary oils | +0.44 | 0.21 | Mild positive trend |

| Eugenol (%) | Dominant constituent in Clove oil | −0.41 | 0.24 | Mild inverse association |

| Trans-Cinnamaldehyde (%) | Major constituent in Cinnamon oil | +0.32 | 0.34 | Weak positive, non-significant |

| Cedrol (%) | Key sesquiterpene in Cedarwood oil | −0.29 | 0.47 | Weak negative trend |

| Compound | χ2 (H) Statistic | df | p-Value | Most Abundant in | Chemical Family | Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Pinene | 18.74 | 7 | <0.001 | Eucalyptus, Spearmint | Monoterpene Hydrocarbon | Associated with moderate antibacterial potential. |

| β-Pinene | 9.32 | 7 | 0.048 | Tea tree, Eucalyptus | Monoterpene Hydrocarbon | Contributes to the volatile and oxidative balance. |

| Limonene | 13.51 | 7 | 0.012 | Lemongrass, Spearmint | Monoterpene Hydrocarbon | Related to solvent-like membrane disruption. |

| 1,8-Cineole | 15.66 | 7 | 0.004 | Eucalyptus, Tea Tree | Oxygenated Monoterpene | Strongly correlated with respiratory antibacterial effect. |

| Eugenol | 21.34 | 7 | <0.001 | Clove, Cinnamon | Phenylpropanoid Derivative | Principal driver of high inhibition zones. |

| Cedrol | 11.87 | 7 | 0.035 | Cedarwood, Rosemary | Sesquiterpene Alcohol | Associated with stability and moderate bioactivity. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muntean, I.; Rusu, L.-C.; Ardelean, L.C.; Tigmeanu, C.V.; Roi, A.; Dinu, S.; Mirea, A.A. The Antibacterial Effect of Eight Selected Essential Oils Against Streptococcus mutans: An In Vitro Pilot Study. Oral 2025, 5, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5040096

Muntean I, Rusu L-C, Ardelean LC, Tigmeanu CV, Roi A, Dinu S, Mirea AA. The Antibacterial Effect of Eight Selected Essential Oils Against Streptococcus mutans: An In Vitro Pilot Study. Oral. 2025; 5(4):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5040096

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuntean, Iulia, Laura-Cristina Rusu, Lavinia Cosmina Ardelean, Codruta Victoria Tigmeanu, Alexandra Roi, Stefania Dinu, and Adina Andreea Mirea. 2025. "The Antibacterial Effect of Eight Selected Essential Oils Against Streptococcus mutans: An In Vitro Pilot Study" Oral 5, no. 4: 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5040096

APA StyleMuntean, I., Rusu, L.-C., Ardelean, L. C., Tigmeanu, C. V., Roi, A., Dinu, S., & Mirea, A. A. (2025). The Antibacterial Effect of Eight Selected Essential Oils Against Streptococcus mutans: An In Vitro Pilot Study. Oral, 5(4), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/oral5040096