1. Introduction

Periodontal disease (PD) is a prevalent immune-mediated inflammatory condition that affects the supporting structures of the teeth [

1,

2,

3]. It is initiated and advanced by dysbiotic subgingival microbiota in susceptible individuals, leading to irreversible damage to tooth-supporting structures and potential tooth loss [

4].

Globally, PD remains one of the leading causes of years lived with disability due to oral disorders, and it affects over one billion people worldwide [

5,

6,

7]. The impact of PD extends beyond clinical burden. It has a significant economic impact, with substantial costs incurred through treatment, loss of productivity, and reduced quality of life [

8,

9].

Conventional diagnostic methods such as clinical attachment loss, probing depth measurements, bleeding on probing are limited in their ability to detect active disease or predict future progression. These methods are mainly retrospective, capturing evidence of past tissue destruction without current disease activity [

10,

11,

12].

The limitations of conventional diagnostic methods highlight the critical need for innovative diagnostic tools capable of detecting the disease at its nascent stages, before irreversible tissue damage occurs. As a result, there is a need for diagnostic tools that can help identify disease in its earliest stages to facilitate prompt treatment and interventions.

Prompt diagnosis plays a crucial role in reducing the burden of periodontal disease [

13]. Advancements in diagnostic approaches have led to the surveillance of biomarkers that provide information on disease status [

14,

15,

16]. Recent advances in PD diagnostics have focused on the detection of pathogen- and host-derived biomarkers in oral fluids [

17,

18]. These biomarkers offer real-time insights into the pathogenesis of PD.

Biomarkers are detected in the oral fluids such as saliva, gingival crevicular fluids (GCF), and oral rinse [

19,

20]. To collect these fluids in clinical settings, clinicians will require minimally invasive fluid sampling diagnostic tools to provide disease status at the point-of-care.

To date, biofluid collection for biomarker detection in oral disease diagnosis has been explored using saliva, oral rinses, and GCF [

21,

22,

23,

24]. The collection of these fluids is by the use of filter paper, oral rinse, capillary pipette, or a more sophisticated microfluidic device [

25,

26,

27]. While these biofluid sampling techniques offer a means to identify potential biomarkers in the diagnosis of oral disease, information on their user friendliness, sampling volume prediction, and minimal invasiveness, as well as their ability to provide real-time disease status, is limited. There is therefore a need to develop a simple, user-friendly, effective, and minimally invasive biofluid sampling diagnostic device that integrates seamlessly into clinical workflows for early point-of-care diagnosis of PD.

Co-design, a collaborative approach to innovation that actively involves end users throughout the design and development process, is notable for its ability to produce contextually relevant and user-acceptable outcomes [

28,

29,

30]. In the development of a diagnostic tool, when healthcare professionals (HCPs) are engaged in the design process, the resulting innovations are more likely to reflect practical clinical needs, facilitate workflow integration, and enhance adoption into clinical practice [

31,

32]. This study represents the first known effort to co-design a minimally invasive biofluid sampling device for PD diagnostics in direct collaboration with HCPs.

To design a biofluid collection device that fulfills end-user requirements, this research adopts a co-design approach, to engage clinicians in the design and development process. In this study, we report on the co-creation of this novel diagnostic device by employing a mixed method approach combining surveys and focus group discussions (FGDs).

2. Materials and Methods

This study adopted a mixed method approach using FGDs and survey questionnaires in the co-design process. A comprehensive protocol was written for both studies and submitted for ethical approval. Ethical approval was granted by the School of Biomedical Sciences Ethics Filter Committee (protocol details: FCBMS-22-177-A, 16 January 2023).

2.1. Recruitment of Participants

The recruitment of participants for FGDs and survey questionnaires was an open call through publicly available email contacts or study flyers circulated on publicly available online platforms. Purposive sampling followed by a snowball strategy was used to identify the niche population of dentists for the FGDs [

33,

34]. Although the recruitment was via emails and social media platforms, the sampling of participants was strategic and purposive.

2.2. Informed Consent

The consent of participants was sought prior to their participation in the study. It is noteworthy that participation was entirely voluntary and that their consent was ongoing throughout the study. Participants were free to opt out of the study at any stage. Each participant was required to read and sign the consent form for the FGD and participant information sheets for the anonymous online survey prior to their participation in the study.

2.3. Study Setting

The study setting was online. Recruitment was an open call through publicly available databases containing emails of potential participants and social media platforms. Focus group discussions were conducted online through Microsoft® Teams and Zoom®. An online survey was conducted on the Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC®) survey platform. The FGDs were conducted at times suitable for participants.

2.4. Data Collection

2.4.1. Focus Group Discussions

Focus group discussions were conducted online due to the geographical diversity of participants, ease of scheduling as participants had varying availability, and health and safety concerns. Online FGDs were conducted on Microsoft Teams and Zoom using a password protected institution computer and participants’ preferred devices. Open ended questions were developed by AM, AJC, and a group of study advisors. A topic guide was also developed to give cues and prompt the schedules for the FDG and to introduce one topic at a time [

35]. The FGD was planned for up to one hour to sustain the attention of participants. The audio from the FGD was recorded and later transcribed for analysis.

Questions for both the FGD and the online survey were grouped into the following four main categories:

Demographics;

Details about their current practices;

Features of the novel biofluid sampling device;

Possibility of using the novel biofluid sampling device in the future.

2.4.2. Online Survey

The questionnaire was developed through a multi-step process. The initial structure and questions were generated from a comprehensive review of literature on point-of-care diagnostics, user-centred design, and technology adoption among HCPs. To establish content validity, the draft questionnaire was reviewed by a panel of two academics, two dentists, two HCPs, and one behavioural scientist. Their feedback was used to refine question wording, sequence, and response scales. The questions were also reviewed by the ethics filter committee to ensure that they were ethically acceptable.

A pilot test was conducted with five HCPs who were not part of the final study sample. This pilot assessed clarity, relevance, and completion time, resulting in minor modifications to enhance readability and flow.

The questionnaire for the online survey was fully anonymised and consisted of dichotomous, Likert scale, and open-ended responses that took approximately 15 min to complete. The JISC® platform was used to administer questionnaires to respondents through emails or a link on the recruitment flyer. Prior to answering the questions, respondents were required to consent to participate in the study.

2.5. Data Analysis

Responses from the online survey were collected using the JISC® survey tool, and at the end of the survey period, all responses were exported as a Microsoft® Excel file and further analysed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS® version 29.0.1).

Data from the FGD was analysed using iterative thematic inquiry that relied heavily on a content analysis of the audio transcripts [

36,

37]. Verbatim transcription of all audio recordings was transcribed first for ease of analysis. During the transcription process, participant names were coded as FGP_1 as a unique identifier. The FGP represents the focus group participant, and the number represents the order in which the participant responded to the discussions. This process was aimed at maintaining the anonymity of participants throughout the rest of the data analysis. The transcripts were reviewed and read thoroughly for data familiarisation to identify themes and effectively generate codes to group the themes [

38,

39].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The choice of inferential tests was guided by the type of data, data distribution, and our study objectives. Demographic information and details about current practices were analysed and presented as frequency distribution. Differences between responses were performed with t-tests, and the possible correlation between continuous data was performed using Pearson’s tests. The internal consistency of Likert scale questions that measure the same construct was measured using the Cronbach alpha value, while individual Likert scale responses were analysed using the Kruskal–Wallis test or Mann–Whitney test. Odds ratio was used to quantify the strength of association between dichotomous data, and chi-square test was used to quantify the differences. These tests were selected for the following reasons: for the normally distributed continuous variables, comparisons between two independent groups were conducted using the independent t-test. When the assumption of normality was not met, the Mann–Whitney U test was used instead. Comparisons across more than two independent groups were performed using the Kruskal–Wallis test. Associations between categorical variables were examined using the chi-square test. The Pearson correlation coefficient was applied to determine the relationship between two continuous, normally distributed variables. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for all analyses. All data for the online survey were analysed with SPSS® version 16.0.

Focus group audios were transcribed, and constant comparison analysis was performed to identify, collate, and report patterns within the data set.

3. Results

This section presents the results of the survey and FGDs using a combination of tables, figures, and quotes from specific participants. While qualitative excerpts offer contextual depth and emphasise the viewpoints influencing these trends, the quantitative data are summarised to highlight vital trends and correlations identified from the study.

In this section, selected representative quotes from participants have been used to illustrate key opinions while preserving readability and clarity.

3.1. Survey

3.1.1. Demographics, Current Clinical Practice, and Perceptions of Current Periodontal Disease Diagnostic Methods

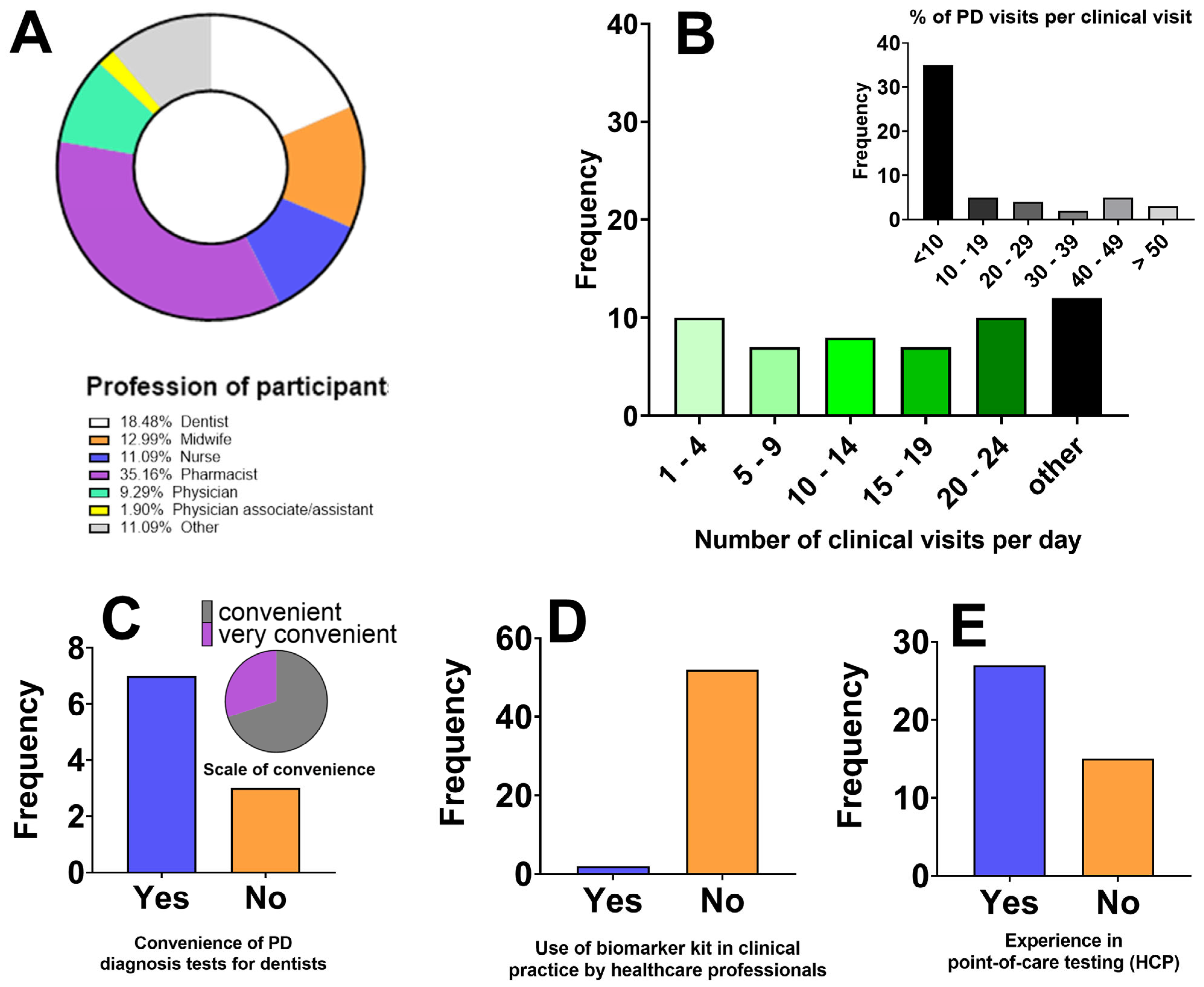

Survey respondents included 54 HCPs between the ages between 18 and 59 years, with 53.7% females and 46.3% males. Participants were grouped according to their profession, as seen in

Figure 1A. Details of participant demographics are presented in

Table 1. Respondents provided insights on the current practices with PD diagnostics. The responses are presented in

Figure 1 below.

3.1.2. Perceived Features and User Preferences for the Proposed Periodontal Disease Diagnostic Device

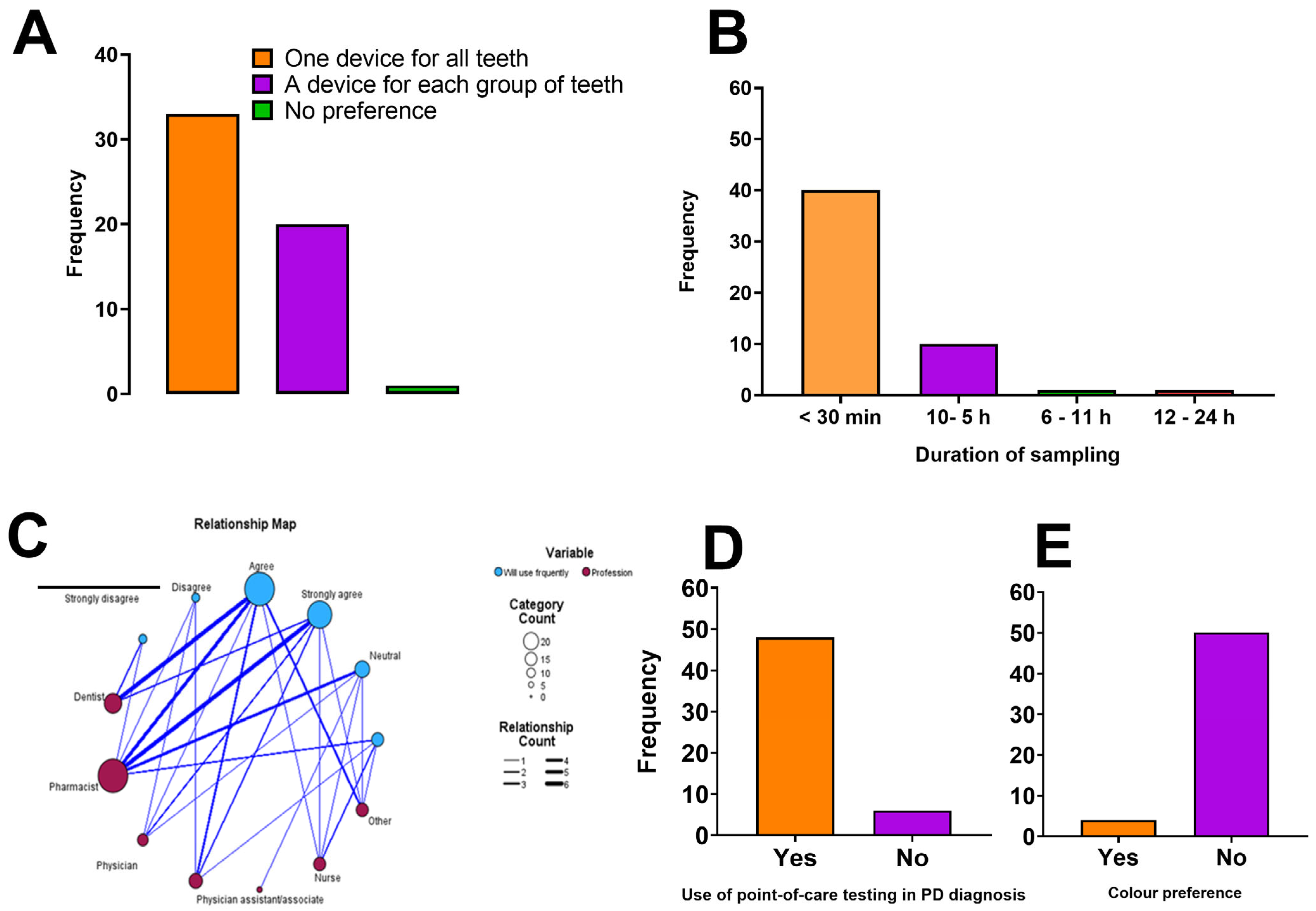

Figure 2 below shows the healthcare professionals concerning the features of the pro-posed periodontal disease (PD) diagnostic device.

3.1.3. Respondents’ Perceptions of Desirable Features and Anticipated Benefits of the Proposed Periodontal Disease Diagnostic Device

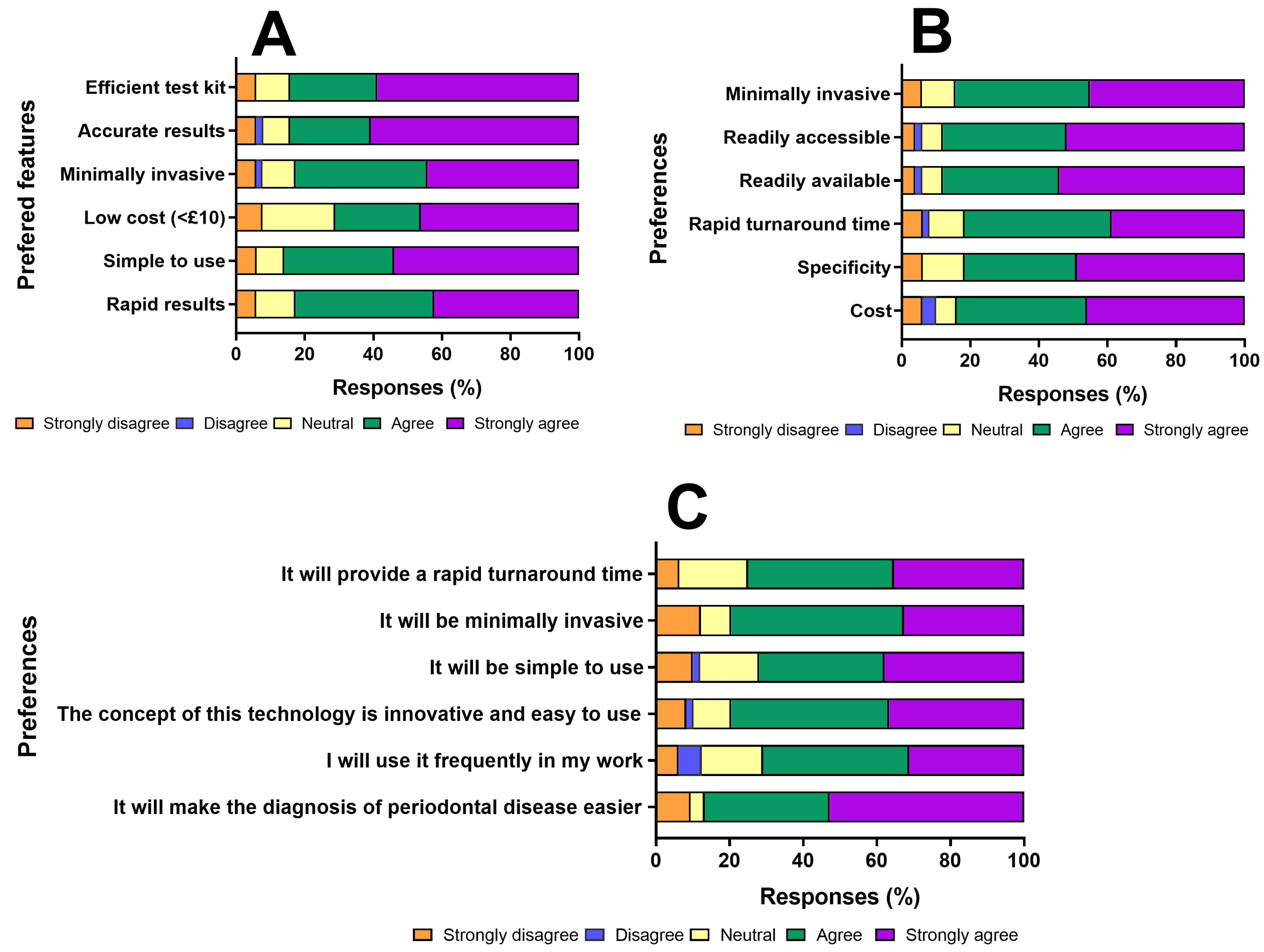

Figure 3 below shows the responses of participants concerning the potential benefits and desirable features of the diagnostic device.

3.2. Focus Group Discussions

3.2.1. Demographics and Themes

A total of two FGDs were conducted to ascertain the opinions of dentists as part of this study. All the dentists voluntarily agreed to participate in this study.

Table 2 summarises the geographic demographics of participants, with 66.7% being males and 33.3% females. Participant names were coded and presented in

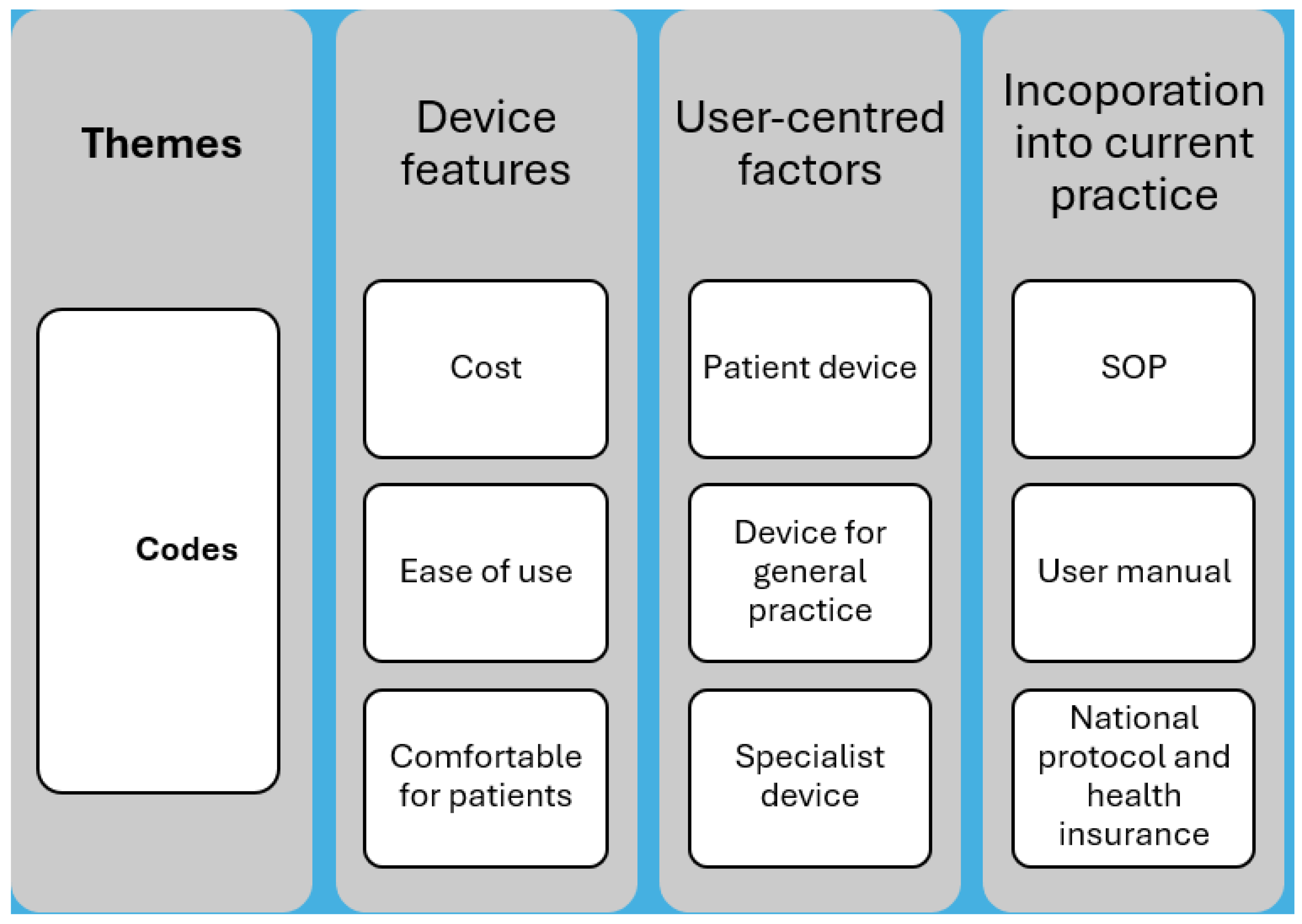

Table 3 in addition to the number of years practiced and their corresponding work sectors. The mean number of years practiced was 4.3 years, with 55.5% working in the private sector and 44.5% in the public sector. Themes and codes were deduced from the transcribed audio of the FGD, and they are presented in

Figure 4.

3.2.2. Current Practices

PD is prevalent in the practices of participants. With COVID restrictions preventing patients from routine check-ups, the prevalence went up post-COVID. In their current practice, a scoring system, basic periodontal examination (BPE), is used depending on the requirements of the national health insurance scheme (NHS) or the facility’s standard operating procedures.

“So we see a lot of it, not fair to say and even more with COVID and people not being able to get in for their routine check up…”

FGP_1

“So you would use your BPE, depending on the scoring of that, then you would move on and do more detailed measurements, pockets, and then the scores that you would get from the depth metric…”

FGP_1

In the diagnosis of PD, signs that are looked for include bleeding on probing, the presence or absence of calculus, among others. Tools that are used to assess patients include William’s probe, a perio-probe for basic periodontal examination (BPE) scoring, and to evaluate pocket depths. Patient’s history, radiographs, and charts are used to support these assessments.

“…And the next one is also you use the X ray as well, but you don’t use any of them in a mutual exclusive manner. You make sure the X ray is kind of helping you with what you are seeing as you do your periodontal probing.”

FGP_8

“You just have to add the history taken, because the history will give you an idea whether you are thinking about a systemic condition that is leading to the period and so you take a detailed history…”

FGP_7

The PD diagnosis starts with PBE scoring, and depending on the score, a full periodontal examination is carried out. All participants confirmed that currently there are no diagnostic test kits used in their practice but mentioned the use of plaque disclosing agents that are used for plaque identification and to encourage good oral hygiene. However, participants acknowledge the need for a diagnostic test kit to improve PD diagnosis.

“…So if it was something that you could use to make a diagnosis that slotted into our classification of periodontal disease, the …. stage and all of those sort of criteria that was something that was able to match into that and it could be useful if it was quicker than what we already do.”

FGP_1

When participants were asked if the current diagnosis of PD was convenient for dentists and patients, the consensus was that the current method is inconvenient for patients and dentists. However, for experienced clinicians, the frequency of performing the diagnosis procedure brought about some ease.

Key challenges with current diagnosis were identified as follows:

Prolonged time for patient assessment

“It does take quite a bit of time to go through each of the pockets.”

FGP_1

“…the time it would take for you to literally probe every tooth, every site, all that can be very consuming…”

FGP_9

Discomfort for patients

“… but sometimes when you do the pocket probing depth, patients can find it quite uncomfortable…”

FGP_2

“It’s very tiring, even though the teeth are like maybe 20 or 32, but even if they’ve lost some and it’s even 20, the fact that you are probing all around one particular teeth, it’s not nice.”

FGP_7

Potential user or operator subjectivity in assessing patients and in the interpretation of results.

“This is sort of thing where there’s a bit of operator subjectivity to the way we would measure Periodontal disease because the way I might probe a tooth will be slightly different to the way X will do it the way Y will do it…”

FGP_3

“…Because what FGP_9 will see in the mouth of a patient and diagnosed because she’s let me say a periodontologist, I may miss it. That is the truth….”

FGP_7

3.2.3. Device Features

Discussions on device features started with whether there was a need for a new device for PD diagnosis. Participants unanimously said yes to a new sampling and testing device by either nodding to other participants’ yes responses or by answering yes with their reasons. Participants mainly expressed their preferences for key characteristics of the sampling device in agreement with needing a new device and with reference to the presentation at the beginning of the FG discussion. They preferred rapid testing, a device that eliminated user subjectivity, a device that tested specific disease states, and enhanced patients’ comfort. Some of these preferences are captured below.

“If it was going to be quick and easy and quantifiable, then yes.”

FGP_1

“Something that’s cheap”

FGP_2

“…so specificity and cost for me should be able to pick that disease irrespective of the race or the environment. There should be cost effective so everybody can get access to it….”

FGP_8

Another feature of the device and sampling techniques discussed was the time frame from sample collection to obtaining results; participants expressed varied opinions based on their preference for the use of the device. According to participants, the time frame will be dependent on the cost, what the patient and clinician want to achieve.

“… the quick response would be good from the point of view of determining whether the patient needs more, like a greater extended treatment…”

FGP_4

“… I think if it gives you a chairside response, it would be useful, like, within a couple of minutes…”

FGP_1

When participants were asked to describe how quick they needed the device to sample fluids, participants said the following:

“… Two to three, max five minutes…”

FGP_1

“… Five to ten minutes…”

FGP_4

Participants, however, recognised that with regard to a play-off between obtaining depth of information from samples versus timeframe, varied timeframes were necessary for specific patient cases.

“… I would only be doing this in specific cases. I wouldn’t be doing this in every patient…”

FGP_5

“… There’s all those specific patients where I think it’s deemed necessary. Personally, I’d be happy to give it a week. I’m like, don’t rush the process…”

FGP_5

“…My answer will be dependent on how much it will cost? Because if it is going to be, let me just say 50 cedis, for an example, 50 cedis for 24 h and maybe 200 cedis for 30 min, I would go for 50 cities. Because not all, but some of this condition might not be an emergency, that we need the treatment the same day…”

FGP_7

The choice between a one-size-fits-all device and one device for each group of teeth was discussed during the FG. Dentists gave the reason for one device for all teeth to be as a result of high-cost implications for the patients or users. Whereas the main reason for having a different device for each set of teeth was the different anatomy of the gingival margin for each set of teeth.

“…Personally I prefer one device for all teeth. I think it’s cost effective in this part of the world…”

FGP_8

“…it’s very important we also get to look at the anatomy of all the teeth and we have groups the molars, premolars and let’s say the anterior. So if they have like three so that the molars are different from the premolars which are different from the anterior, I think it will be perfect…”

FGP_7

Dentists identified the role of patients’ beliefs in connection with waiting times. Interestingly, some patients believe that the longer the time taken for results to be ready, the more authentic and detailed the results are.

“…I think also what was said on waiting away, people love you know getting bloods done… whatever, I don’t know that much about that… People love slight statistics and know they got a test, So they might take it a bit more seriously if there’s a lot of more details…”

FGP_2

3.2.4. Usefulness of the Device to Patients and Clinicians

When asked about how useful this device is perceived to be for patients and clinicians, a stratified use of the device was identified by participants. With patients having an at home testing device, a device developed specifically for routine tests in general practice, and a device for specialist use. Additionally, participants wanted a device that improves current PD diagnosis in general.

“…. In general practice, yes, it might be nice to gather all the information, but I don’t know how applicable it would be to the patient’s care…”

FGP_1

“…So maybe the more complicated ones to the specialist and then the one that everybody can use to the general practitioners…”

FGP_8

Suggestions for costing the device were made by dentists. Based on their clientele and experiences, they commented that the cost of the device will be dependent on the target market. For example, the product must be cost effective for NHS routine tests and different for specific patient cohorts.

“…. So I wouldn’t want to be in the rush to pay more. But of course, if we can get it earlier and it is cheaper, I’ll go for the option. But for now, my first thing I’m going to look at is how much it will cost per time. So I can give you I want it to be 30 min or 1 h, but the cheaper one is what I’ll go for.…”

FGP_7

“… a smaller cohort of patients are more invested in it and there was more of a reason for it, you might then be able to charge more for it and the patients might be willing to pay more for it…”

FGP_1

“… if we can design something that you can achieve specificity with the minimum cost, I’ll prefer that…”

FGP_8

3.2.5. Recommendations for the Research Team

Nearing the end of the FG discussion, participants made recommendations for the research team. These recommendations were centred on considerations for an eco-friendly device and waste management strategies, stratification of depth of information from the device for different user groups, packaging details, simplicity of the device, and training for users. The need for a seamless transition into their current protocols and disease classification was also echoed.

“… If you were going to market this, you might need to provide some training. If you were going to bring it out to practice, you might need to come out and talk all of the dentists through how to use how you read it to make it easier to use…”

FGP_4

“… It would need to be quite easy, not bulky for waste as well…”

FGP_3

“… So if it was something that you could use to make a diagnosis that slotted into our classification of periodontal disease, the …. stage and all of those sort of criteria that was something that was able to match into that…”

FGP_1

Participants also expressed concerns about shelf life, storage of the device, and the specialist use of the device. Concerns about making the device accessible to all were also raised.

“… What is the shelf like on the hydrogel?…”

FGP_2

“… You are wanting something that you don’t have to go up to the fridge…”

FGP_5

“…Sometimes when you make these things available to all general dentists, the tendency that they will start keeping these cases till treatment becomes very dire or prognosis becomes very poor, and then now they ship the patients to you. Once they feel like they have the diagnostics, now they want to take over that patient care, then they only bring the patient when they realise the fact that they can’t do anything about it and things have gotten worse, then they ship the patient…”

FGP_9

4. Discussion

This study uses a user centred, participatory design framework to bring together the perspectives and expertise of a multidisciplinary cohort of HCPs, particularly dentists, to support the co-development of a novel biofluid sampling device intended for point-of-care diagnosis of PD. Previous studies in other research areas showed that product design processes that incorporate early and frequent engagement with stakeholders have a high probability of creating a positive impact in addressing previous user challenges and improving sustained use of such devices [

40,

41,

42]. Based on this evidence, this study used survey questionnaires and FGDs as qualitative methods to explore the views of HCPs on the novel hydrogel biofluid sampling device. The qualitative and quantitative data were analysed separately, and the data were subsequently integrated for interpretation. Integration occurred through a process of comparison and convergence, in which quantitative findings were examined alongside qualitative themes to identify areas of agreement or divergence. A summary of this integration is presented in a joint display table (

Supplementary Table S1). Based on the modest sample size for the online survey (

n = 54), the quantitative analysis of this study was exploratory.

4.1. Problems with Current Practice

Despite the existence of established diagnostic protocols for PD, participants reported persistent challenges that impede optimal diagnosis. Across routine clinical encounters, HCP reported attending at least five suspected PD cases daily. While dentists conduct definitive diagnoses, other HCPs, such as pharmacists and nurses, are frequently approached by patients with oral health concerns; hence, need for a more accessible diagnostic tool.

Three main challenges with current diagnostic approaches emerged during the interactions with participants. Firstly, current diagnostic practices are time-consuming [

43]. Periodontal probing requires up to 15 min per patient under ideal conditions, and longer when more detailed assessment is involved, prolonging clinical visits. Secondly, the PD diagnosis procedure can be physically uncomfortable for patients and ergonomically fatiguing for clinicians, relying on invasive probing of sensitive gingival tissues [

44]. Thirdly, PD diagnosis is vulnerable to operator subjectivity, as interpretation of radiographs and grading can differ between clinicians, introducing variability despite standardised guidelines. Such subjectivity is not unique to PD and is echoed in other diagnostic contexts, such as cervical cancer, where the interpretation of colposcopy results is also susceptible to user subjectivity [

45]. Collectively, these challenges highlight the need for innovative diagnostic tools that are rapid, minimally invasive, and feasible within the current workflow of healthcare practitioners.

4.2. Advantages of Using the Oral Fluid Sampling Device

An inclusive co-design approach fosters product relevance and sustainability [

46]. HCPs in this study contributed not only as clinicians but also as patients and caregivers, using their accumulated knowledge to influence both immediate and future device development. Participants with limited experience of point-of-care (POC) testing nonetheless strongly supported its application for PD. Over 80% of survey respondents agreed that the proposed device would simplify diagnosis, citing its innovative concept, ease of use, minimally invasive nature, and rapid turnaround time, importantly, participants’ willingness to use the device was significantly associated with their perception of its utility, aligning with reports that behavioural change within institutions is underpinned by individual clinician adoption. The FGD highlighted expectations such as speed, quantifiability, reliability, comfort, affordability, and simplicity. These features mirrored previously identified advantages of POC testing reported by Zhang et al. [

47].

4.3. Desirable Device Features Practical Use

Contemporary medical device research increasingly mandates end-user input to ensure clinical acceptability and integration [

48,

49,

50]. This study approach is centred on priority-setting frameworks, which emphasise the provision of evidence and inclusion of diverse perspectives [

49]. The survey and FGD findings revealed that clinicians prioritised diagnostic accuracy, simplicity of use, low cost, availability, and accessibility as the most influential determinants of adoption, followed closely by device specificity, turnaround time, and minimal invasiveness. Such insights are consistent with Coulentianos et al., who identified affordability, appropriateness, accessibility, and availability as essential for sustainable device use, especially in low- and middle-income contexts [

42].

Sampling preferences emerged as a key design consideration. While 30% of HCP preferred a single device for all teeth to minimise costs, 20% favoured tooth-specific devices, citing anatomical variations in gingival sulcus width. These insights are valuable as the intended material for our oral fluid sampling device has tuneable mechanical and absorptive properties to offer flexibility in accommodating both preferences. On turnaround time, a rapid result of 10–15 min was deemed ideal for screening purposes, whereas longer processing times of up to one week were acceptable in follow-up or severity-monitoring cases. Specificity was defined not only as distinguishing between gingivitis and periodontitis, but also as capturing biomarker profiles relevant to disease onset, progression, remission, and therapeutic efficacy. Further, participants recommended stratified device versions tailored to screening by general practitioners, specialists, and at-home testing. This provided a nuanced perspective that could enable triaged PD care.

4.4. Concerns Regarding the Use of the Device

The early-stage co-design approach provided a platform for surfacing tacit concerns that might otherwise remain unidentified. To guide product iteration and to ensure clinical feasibility, these concerns are crucial at the product development stage to inform the design of the device. Storage conditions was a key issue raised by participants. A device requiring refrigeration could introduce infrastructural burdens, incur costs, delay patient turnover, and reduce convenience. This, participants preferred room-temperature stable versions of the device. Concerns were also raised about universal use across clinical levels. Clinicians were concerned about inappropriate case escalation or misinterpretation of results if all HCPs used a complex device without adequate training. Additionally, interpretational challenges could undermine patient confidence in non-dental professionals. To date, no existing study has explored a stratified biocompatible device for different PD diagnoses. From this study, a proposed approach is to have a staged product development. First a single-analyte detection device for screening, followed by a multi-analyte version as preclinical evidence advances.

4.5. Recommendation to the Research Team

Participants consistently recommend device integration within routine clinical workflows and institutional policies as central to promoting it use, as failure to align with workflow requirements is a major barrier to new technology implementation [

51]. Training and user guidance were highly recommended. Ambiguous instructions, unclear order of use, unfamiliar terminology or symbols, and language barriers can contribute significantly to user error [

52]. Participants therefore advocated comprehensive yet straightforward training materials and user manuals. The literature suggests that well-structured training enhances uptake and appropriate use of novel devices [

53]. The recommendations collated through this study were mapped onto actionable steps, including exploring biocompatible, biodegradable options for the device material to address waste concerns, and prioritising design parameters consistent with existing in-house target product profiles. To close the participatory co-design loop, the study team must update participants on progress, outcomes, and the incorporation of their input to encourage continued engagement and ownership. This study represents an early phase of the translational pathway for the proposed biofluid sampling device. Future work will involve prototype optimisation, biomarker validation, and compliance with regulatory standards to ensure clinical applicability and scalability.

4.6. Limitations of the Study

This study had some limitations. Firstly, the sample size of both survey and focus group participants was relatively small, potentially limiting generalisability across wider geographical or institutional settings. Secondly, participation was voluntary, introducing the possibility of selection bias; those enthusiastic about innovation may have been overrepresented. Thirdly, although multidisciplinary, most participants were dentists, potentially skewing feedback towards dental-centric rather than general practice implementation. Finally, while the co-design process yielded meaningful qualitative insights, quantitative validation of device functionality and diagnostic performance lies beyond the scope of this study and remains a necessary next step.

5. Conclusions

This study successfully applies a user-centred, co-design approach to the development of a gingival crevicular fluid sampling device for point-of-care PD diagnosis. By integrating survey responses and focus group feedback, this research provided a pragmatic strategy for capturing HCPs perspectives at an early stage of device design. Involvement of clinicians yielded in-depth insights into both the current diagnostic challenges and the features required for a clinically acceptable innovation.

The findings confirmed that current PD diagnostic methods remain time-consuming, invasive, and operator-dependent, emphasising the need for rapid, user-friendly, minimally invasive alternatives. Participants highlighted clear advantages of the proposed sampling device, including its innovation, simplicity, comfort, and potential for rapid turnaround. Desired device features were strongly centred on diagnostic accuracy, cost-effectiveness, accessibility, minimal invasiveness, and seamless workflow integration. Crucially, participants also identified stratified use cases and emphasised the importance of appropriate training and user guidance. Their concerns about storage conditions, interpretation of results, and practical usability provide essential direction for ongoing development.

While the limitations of current PD diagnostic practices are well established, the novelty of this study lies in its participatory approach. By engaging HCP in the co-design process, this work moves beyond identifying diagnostic gaps to demonstrate how user-centred input can directly shape the design of innovative diagnostic devices.

Despite a relatively small cohort, the qualitative richness of this study offers critical evidence to inform prototype fabrication and iterative optimisation of the device. Future work will focus on translating these user-derived requirements into technical specifications and manufacturing processes, followed by clinical performance testing. Engaging end-users early and meaningfully strengthens product relevance, supports future adoption, and enhances the likelihood of successful market translation. By integrating the voices of dentists and other HCPs, this work lays a robust foundation for the development of an effective, user-driven, point-of-care diagnostic tool for periodontal disease. Building on these findings, the next stage of this research will focus on prototype fabrication and laboratory validation, guided by the user-identified design specifications from this study into the technical development process. This will be followed by biomarker screening, usability assessment, and regulatory guideline evaluation to ensure that the device meets both scientific and clinical standards.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.J.C., L.M. (Lyndsey McMullan) and A.M.; methodology, A.J.C., L.M. (Lynsey McMullan), L.M. (Leonard Maguire) and A.M.; analysis, A.M. and C.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.; writing—review and editing, A.M., A.J.C., C.B., A.A. and R.I.S.; visualisation, A.M. and C.B.; supervision, A.J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Department for the Economy, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom, through Ulster University as part of the researcher training funds with funding number: 84212Q.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of ULSTER UNIVERSITY School of Biomedical Sciences Ethics Filter Committee (FCBMS) with protocol code: FCBMS-22-177-A on 16 January 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

For details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, please contact the corresponding author at

a.courtenay@ulster.ac.uk.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all dentists and healthcare professionals who participated in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Lyndsey McMullan and Leonard Maguire are employed by the company DJ Maguire and Associates, and they contributed to the design of the methodology of this study. They have no financial or commercial conflicts of interest. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Wadia, R.; Walter, C.; Chapple, I.L.C.; Ower, P.; Tank, M.; West, N.X.; Needleman, I.; Hughes, F.J.; Milward, M.R.; Hodge, P.J.; et al. Periodontal diagnosis in the context of the 2017 classification system of periodontal diseases and conditions: Presentation of a patient with periodontitis localised to the molar teeth. Br. Dent. J. 2019, 226, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, C.; Chapple, I.L.; Ower, P.; Tank, M.; West, N.X.; Needleman, I.; Wadia, R.; Milward, M.R.; Hodge, P.J.; Dietrich, T. Periodontal diagnosis in the context of the BSP implementation plan for the 2017 classification system of periodontal diseases and conditions: Presentation of a patient with severe periodontitis following successful periodontal therapy and supportive periodontal treatment. Br. Dent. J. 2019, 226, 411–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, N.P.; Bartold, P.M. Periodontal health. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, S9–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitz-Mayfield, L.J. Conventional diagnostic criteria for periodontal diseases (plaque-induced gingivitis and periodontitis). Periodontology 2000 2024, 95, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019); Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME): Seattle, WA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Oral Health Status Report: Towards Universal Health Coverage for Oral Health by 2030. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061484 (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Bernabe, E.; Marcenes, W.; Abdulkader, R.S.; Abreu, L.G.; Afzal, S.; Alhalaiqa, F.N.; Al-Maweri, S.; Alsharif, U.; Anyasodor, A.E.; Arora, A.; et al. Trends in the global, regional, and national burden of oral conditions from 1990 to 2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2025, 405, 897–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Jiang, J.; Li, J.; Mou, J.; Liu, N.; Yuan, J.; Huang, G.; Liu, J. The global, regional, and national burden of oral disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2021, and projections to 2050: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Regenesis Repair Rehabil. 2025, 1, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Oral Health. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/oral-health (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Renatus, A.; Trentzsch, L.; Schönfelder, A.; Schwarzenberger, F.; Jentsch, H. Evaluation of an electronic periodontal probe versus a manual probe. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2016, 10, ZH03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elashiry, M.; Meghil, M.M.; Arce, R.M.; Cutler, C.W. From manual periodontal probing to digital 3-D imaging to endoscopic capillaroscopy: Recent advances in periodontal disease diagnosis. J. Periodontal Res. 2019, 54, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voinescu, I.; Ferechide, D.; Cristache, C.M.; Burlibasa, L.; Burlibasa, M. Ethical and legal aspects in periodontal disease diagnosis and therapy. Rom. J. Leg. Med. 2019, 27, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korgaonkar, J.; Tarman, A.Y.; Koydemir, H.C.; Chukkapalli, S.S. Periodontal disease and emerging point-of-care technologies for its diagnosis. Lab Chip 2024, 24, 3326–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Giménez, J.L.; Seco-Cervera, M.; Tollefsbol, T.O.; Romá-Mateo, C.; Peiró-Chova, L.; Lapunzina, P.; Pallardó, F.V. Epigenetic biomarkers: Current strategies and future challenges for their use in the clinical laboratory. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2017, 54, 529–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Paek, S.H.; Choi, D.Y.; Lee, M.K.; Park, J.N.; Cho, H.M.; Paek, S.H. Real-time monitoring of biomarkers in serum for early diagnosis of target disease. BioChip J. 2020, 14, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, M.; Torabinejad, M.; Angelov, N.; Ojcius, D.M.; Parang, K.; Ravnan, M.; Lam, J. Bridging oral and systemic health: Exploring pathogenesis, biomarkers, and diagnostic innovations in periodontal disease. Infection 2025, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Könönen, E.; Gursoy, M.; Gursoy, U. Periodontitis: A multifaceted disease of tooth-supporting tissues. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-García, M.; Hernández-Lemus, E. Periodontal Inflammation and Systemic Diseases: An Overview. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 709438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munshi, M.A.; Almozher, H.A.; Alqahtani, F.A.; Youssef, M.M.; Almtere, A.S.; Alsadoon, B.K.; Alotheem, L.S.; Alhowirini, L.F.; Alotaibi, A.M.; Almutairi, A.A.; et al. Types, accuracy, and efficacy of salivary biomarkers in periodontal diagnosis. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2023, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghallab, N.A. Diagnostic potential and future directions of biomarkers in gingival crevicular fluid and saliva of periodontal diseases: Review of the current evidence. Arch. Oral Biol. 2018, 87, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, F.; Liu, W.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Xian, Y.; Sujanamulk, B. Predictive salivary biomarkers for early diagnosis of periodontal diseases–current and future developments. Turk. J. Biochem. 2023, 48, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, S.S.; Abdulkareem, A.A.; Sha, A.M.; Rawlinson, A. Diagnostic accuracy of oral fluids biomarker profile to determine the current and future status of periodontal and peri-implant diseases. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, S.P.; Williams, R.; Offenbacher, S.; Morelli, T. Gingival crevicular fluid as a source of biomarkers for periodontitis. Periodontology 2000 2016, 70, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bibi, T.; Khurshid, Z.; Rehman, A.; Imran, E.; Srivastava, K.C.; Shrivastava, D. Gingival crevicular fluid (GCF): A diagnostic tool for the detection of periodontal health and diseases. Molecules 2021, 26, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Shen, M.M.; Liu, X.J.; Si, Y.; Yu, G.Y. Characteristics of the saliva flow rates of minor salivary glands in healthy people. Arch. Oral Biol. 2015, 60, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittman, T.W.; Decsi, D.B.; Punyadeera, C.; Henry, C.S. Saliva-based microfluidic point-of-care diagnostic. Theranostics 2023, 13, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazar Majeed, Z.; Philip, K.; Alabsi, A.M.; Pushparajan, S.; Swaminathan, D. Identification of gingival crevicular fluid sampling, analytical methods, and oral biomarkers for the diagnosis and monitoring of periodontal diseases: A systematic review. Dis. Markers 2016, 2016, 1804727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsci, S.; Kurosu, M.; Federici, S.; Mele, M.L. Computer Systems Experiences of Users With and Without Disabilities; Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Thabrew, H.; Fleming, T.; Hetrick, S.; Merry, S. Co-design of eHealth interventions with children and young people. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantin, N.; Edward, H.; Ng, H.; Radisic, A.; Yule, A.; D’Asti, A.; D’Amore, C.; Reid, J.C.; Beauchamp, M. The use of co-design in developing physical activity interventions for older adults: A scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.; Johansenb, E. Human-centered design for medical devices and diagnostics in global health. Glob. Health Innov. 2020, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, W.; Park, S.Y.; Zhang, Z.; Singh, H.; Pasupathy, K.; Mahajan, P. Identifying Interventions to Improve Diagnostic Safety in Emergency Departments: Protocol for a Participatory Design Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2024, 13, e55357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.; Scott, S.; Geddes, A. Snowball sampling. In SAGE Research Methods Foundations; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt, A.E. Sampling methods. J. Hum. Lact. 2020, 36, 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busetto, L.; Wick, W.; Gumbinger, C. How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurol. Res. Pract. 2020, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.L.; Nica, A. Iterative thematic inquiry: A new method for analyzing qualitative data. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19, 1609406920955118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihas, P. Qualitative Research Methods: Approaches to Qualitative Data Analysis; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn, P.; Turner, C. Decoding via coding: Analyzing qualitative text data through thematic coding and survey methodologies. J. Libr. Adm. 2016, 56, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.; Moser, T. The art of coding and thematic exploration in qualitative research. Int. Manag. Rev. 2019, 15, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, U.; Regan, A. Co-designing a smartphone app for and with farmers: Empathising with end-users’ values and needs. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 82, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.F.; Acha, B.V.; García, M.F. Co-design for people-centred care digital solutions: A literature review. Int. J. Integr. Care 2021, 21, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulentianos, M.J.; Rodriguez-Calero, I.; Daly, S.R.; Sienko, K.H. Global health front-end medical device design: The use of prototypes to engage stakeholders. Dev. Eng. 2020, 5, 100055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dental, S. Prevention and Treatment of Periodontal Diseases in Primary Care Dental Clinical Guidance; Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme: Dundee, Scotland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, M.H.; Rädel, M. Utilization and expenses in dental care: An overview based on routine data from Germany. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2021, 64, 993–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, P.; Ng, M.T.A.; Qiao, Y. The challenges of colposcopy for cervical cancer screening in LMICs and solutions by artificial intelligence. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, M.; McGillion, M.; Chambers, E.M.; Dix, J.; Fajardo, C.J.; Gilmour, M.; Levesque, K.; Lim, A.; Mierdel, S.; Ouellette, C.; et al. A generative co-design framework for healthcare innovation: Development and application of an end-user engagement framework. Res. Involv. Engag. 2021, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Tis, T.B.; Wei, Q. Smartphone-Based Clinical Diagnostics, in Precision Medicine for Investigators, Practitioners and Providers; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 493–508. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L.J.; Dickinson, T.; Smith, S.; Brown Wilson, C.; Horne, M.; Torkington, K.; Simpson, P. Openness, inclusion and transparency in the practice of public involvement in research: A reflective exercise to develop best practice recommendations. Health Expect. 2018, 21, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Hinton, L.; Finlay, T.; Macfarlane, A.; Fahy, N.; Clyde, B.; Chant, A. Frameworks for supporting patient and public involvement in research: Systematic review and co-design pilot. Health Expect. 2019, 22, 785–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindblom, S.; Flink, M.; Elf, M.; Laska, A.C.; von Koch, L.; Ytterberg, C. The manifestation of participation within a co-design process involving patients, significant others and health-care professionals. Health Expect. 2021, 24, 905–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, D.; Petrina, N.; Young, N.; Cho, J.G.; Poon, S.K. Understanding the factors influencing acceptability of AI in medical imaging domains among healthcare professionals: A scoping review. Artif. Intell. Med. 2023, 147, 102698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swogger, M.T.; Smith, K.E.; Garcia-Romeu, A.; Grundmann, O.; Veltri, C.A.; Henningfield, J.E.; Busch, L.Y. Understanding kratom use: A guide for healthcare providers. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 801855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, L.; Kaihlanen, A.M.; Laukka, E.; Gluschkoff, K.; Heponiemi, T. Behavior change techniques to promote healthcare professionals’ eHealth competency: A systematic review of interventions. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2021, 149, 104432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Overview of respondent demographics, clinical practice characteristics, and perceptions of current periodontal disease diagnostic methods. Where: (A) Distribution of participants by professional background, illustrating the multidisciplinary nature of respondents, including dentists, midwives, nurses, pharmacists, physicians, physician associates/assistants, and other healthcare professionals. (B) Reported number of clinical visits per day among healthcare professionals and the percentage of those visits related to periodontal disease (inset). (C) Responses from dentists regarding the perceived convenience of currently available PD diagnostic tests, indicating the proportion of those who find existing tests convenient versus inconvenient for routine use with a detailed scale of convenience ratings for current PD diagnostic tests among dentists (inset). (D) Use of biomarker kits in current clinical practice, highlighting the limited incorporation of biomarker-based diagnostic tools among respondents. (E) Experience of healthcare professionals with point-of-care (POC) diagnostic testing, showing varying familiarity with rapid diagnostic technologies.

Figure 1.

Overview of respondent demographics, clinical practice characteristics, and perceptions of current periodontal disease diagnostic methods. Where: (A) Distribution of participants by professional background, illustrating the multidisciplinary nature of respondents, including dentists, midwives, nurses, pharmacists, physicians, physician associates/assistants, and other healthcare professionals. (B) Reported number of clinical visits per day among healthcare professionals and the percentage of those visits related to periodontal disease (inset). (C) Responses from dentists regarding the perceived convenience of currently available PD diagnostic tests, indicating the proportion of those who find existing tests convenient versus inconvenient for routine use with a detailed scale of convenience ratings for current PD diagnostic tests among dentists (inset). (D) Use of biomarker kits in current clinical practice, highlighting the limited incorporation of biomarker-based diagnostic tools among respondents. (E) Experience of healthcare professionals with point-of-care (POC) diagnostic testing, showing varying familiarity with rapid diagnostic technologies.

![Oral 05 00095 g001 Oral 05 00095 g001]()

Figure 2.

Preferences and perceptions of healthcare professionals regarding features of the proposed periodontal disease (PD) diagnostic device. (A) Sampling preference among participants indicated the majority favoured a single device suitable for all teeth rather than separate devices for different tooth groups. (B) Preferred duration of sampling, with a strong inclination towards rapid testing, with most respondents favouring sampling times under 30 min. (C) Relationship map illustrating associations between professional groups and their frequency of intended use of the proposed PD diagnostic device. The thickness of the connecting lines represents the strength of association, while node size reflects response count within each professional category. (D) Previous use of point-of-care testing by participants in PD diagnosis shows familiarity and potential readiness for adoption of the novel diagnostic tool. (E) Colour preference for the proposed diagnostic device shows a minority preference for a coloured device.

Figure 2.

Preferences and perceptions of healthcare professionals regarding features of the proposed periodontal disease (PD) diagnostic device. (A) Sampling preference among participants indicated the majority favoured a single device suitable for all teeth rather than separate devices for different tooth groups. (B) Preferred duration of sampling, with a strong inclination towards rapid testing, with most respondents favouring sampling times under 30 min. (C) Relationship map illustrating associations between professional groups and their frequency of intended use of the proposed PD diagnostic device. The thickness of the connecting lines represents the strength of association, while node size reflects response count within each professional category. (D) Previous use of point-of-care testing by participants in PD diagnosis shows familiarity and potential readiness for adoption of the novel diagnostic tool. (E) Colour preference for the proposed diagnostic device shows a minority preference for a coloured device.

![Oral 05 00095 g002 Oral 05 00095 g002]()

Figure 3.

Preferences and perceptions of healthcare professionals regarding desirable features and anticipated benefits of a proposed periodontal disease (PD) diagnostic device. Where: (A) Participants’ preferred design features for the diagnostic device, demonstrating strong agreement for characteristics such as efficiency, accuracy, minimal invasiveness, affordability (≤£10), ease of use, and rapid results. (B) Preferences related to device accessibility and performance attributes, highlighting prioritisation of minimally invasive sampling, rapid turnaround time, specificity, and cost-effectiveness as vital determinants of clinical adoption. (C) Anticipated benefits and intentions of use among healthcare professionals, showing high levels of agreement that the device would simplify and enhance PD diagnosis.

Figure 3.

Preferences and perceptions of healthcare professionals regarding desirable features and anticipated benefits of a proposed periodontal disease (PD) diagnostic device. Where: (A) Participants’ preferred design features for the diagnostic device, demonstrating strong agreement for characteristics such as efficiency, accuracy, minimal invasiveness, affordability (≤£10), ease of use, and rapid results. (B) Preferences related to device accessibility and performance attributes, highlighting prioritisation of minimally invasive sampling, rapid turnaround time, specificity, and cost-effectiveness as vital determinants of clinical adoption. (C) Anticipated benefits and intentions of use among healthcare professionals, showing high levels of agreement that the device would simplify and enhance PD diagnosis.

Figure 4.

An illustration of the themes and corresponding codes extracted from the FGDs. Where SOP represents standard operating procedures.

Figure 4.

An illustration of the themes and corresponding codes extracted from the FGDs. Where SOP represents standard operating procedures.

Table 1.

Demographics of respondents of online survey.

Table 1.

Demographics of respondents of online survey.

| Characteristics | Number of Responses (N) | Percentage (%) |

|---|

| Overall | 54 | |

| Age (years) | | |

| <30 | 13 | 24.1 |

| 30–34 | 33 | 61.1 |

| 35–39 | 6 | 11.1 |

| 45–49 | 1 | 1.9 |

| 55–59 | 1 | 1.9 |

| Total | 54 | 100 |

| Sex | | |

| Male | 25 | 46.3 |

| Female | 29 | 53.7 |

| Total | 54 | 100 |

| Work sector | | |

| Predominantly public | 20 | 37.0 |

| Predominantly private | 15 | 27.8 |

| Public and private | 16 | 29.6 |

| Other | 3 | 5.6 |

| Total | 54 | 100 |

Table 2.

Demographics of participants of FGDs detailing their geographical location and gender.

Table 2.

Demographics of participants of FGDs detailing their geographical location and gender.

| Focus Group Number | Number of Participants | Country of Practice |

|---|

| | Male | Female | |

|---|

| 1 | 3 | 2 | United Kingdom (Northern Ireland) |

| 2 | 3 | 1 | Ghana |

| Total | 6 | 3 | |

Table 3.

Demographic details of participants of focus groups detailing participants’ codes, years of practice and work sectors.

Table 3.

Demographic details of participants of focus groups detailing participants’ codes, years of practice and work sectors.

| Participant Identifier | Number of Years Practiced (Years) | Work Sector |

|---|

| FGP_1 | 7 | Private |

| FGP_2 | 4 | Private |

| FGP_3 | 11 | Private |

| FGP_4 | 4 | Private |

| FGP_5 | 5 | Private |

| FGP_6 | 8 | Public |

| FGP_7 | 8 | Public |

| FGP_8 | 8 | Public |

| FGP_9 | 8 | Public |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).