Design of Experiments Methodology for Fused Filament Fabrication of Silicon-Carbide-Particulate-Reinforced Polylactic Acid Composites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Printability

3.2. Microstructural Analysis

3.3. Compression Data and Analysis

3.4. Tensile Data and Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AM | Additive manufacturing |

| FFF | Fused Filament Fabrication |

| PLA | Polylactic acid |

| DIC | Digital image correlation |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| SiC | Silicon Carbide |

Appendix A

References

- Singh, N.; Siddiqui, H.; Koyalada, B.S.R.; Mandal, A.; Chauhan, V.; Natarajan, S.; Kumar, S.; Goswami, M.; Kumar, S. Recent Advancements in Additive Manufacturing (AM) Techniques: A Forward-Looking Review. Met. Mater. Int. 2023, 29, 2119–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fico, D.; Rizzo, D.; Casciaro, R.; Esposito Corcione, C. A Review of Polymer-Based Materials for Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF): Focus on Sustainability and Recycled Materials. Polymers 2022, 14, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouri, N.G.; Bahú, J.O.; Blanco-Llamero, C.; Severino, P.; Concha, V.O.C.; Souto, E.B. Polylactic Acid (PLA): Properties, Synthesis, and Biomedical Applications—A Review of the Literature. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1309, 138243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lei, Q.; Xing, S. Mechanical Characteristics of Wood, Ceramic, Metal and Carbon Fiber-Based PLA Composites Fabricated by FDM. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 3741–3751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Halbig, M.C.; Singh, M. Particulate Reinforced Polymer Matrix Composites: Tribological Behavior and 3D Printing by Fused Filament Fabrication. AMP Tech. Artic. 2020, 178, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakharia, V.S.; Kuentz, L.; Salem, A.; Halbig, M.C.; Salem, J.A.; Singh, M. Additive Manufacturing and Characterization of Metal Particulate Reinforced Polylactic Acid (PLA) Polymer Composites. Polymers 2021, 13, 3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranaiefar, M.; Singh, M.; Salem, J.A.; Halbig, M.C. Compressive Properties of Additively Manufactured Metal-Reinforced PLA and ABS Composites. Polymers 2024, 16, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, L.K.; Ramu, M.; Singamneni, S.; Binudas, N. Strength Evaluation of Polymer Ceramic Composites: A Comparative Study between Injection Molding and Fused Filament Fabrication Techniques. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 10, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Siraj, S.; Al-Marzouqi, A.H. 3D Printing PLA Waste to Produce Ceramic Based Particulate Reinforced Composite Using Abundant Silica-Sand: Mechanical Properties Characterization. Polymers 2020, 12, 2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedjazi, L.; Guessasma, S.; Belhabib, S.; Stephant, N. On the Mechanical Performance of Polylactic Material Reinforced by Ceramic in Fused Filament Fabrication. Polymers 2022, 14, 2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahay, R.; Nayak, R.; Naik, N.; Tambrallimath, V. Influence of Silicon Carbide Reinforcement on Mechanical Behavior of 3D Printed Polymer Composites. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 5991–5996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.K.; Giri, J.; Sathish, T.; Kanan, M.; Prajapati, D. Influence of 3D Printing Process Parameters on Mechanical Properties of PLA Based Ceramic Composite Parts. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 104488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.K.; Hetzer, M.; De Kee, D. PLA/Clay/Wood Nanocomposites: Nanoclay Effects on Mechanical and Thermal Properties. J. Compos. Mater. 2011, 45, 1145–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, H.; Yin, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, W. Compressive Properties of 3D Printed Polylactic Acid Matrix Composites Reinforced by Short Fibers and SiC Nanowires. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2019, 21, 1800539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartal, F. Mechanical Performance Optimization in FFF 3D Printing Using Taguchi Design and Machine Learning Approach with PLA /Walnut Shell Composites Filaments. Vinyl Addit. Technol. 2025, 31, 622–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalihan, R.D.; Aggari, J.C.V.; Alon, A.S.; Latayan, R.B.; Montalbo, F.J.P.; Javier, A.D. On the Optimized Fused Filament Fabrication of Polylactic Acid Using Multiresponse Central Composite Design and Desirability Function Algorithm. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process Mech. Eng. 2024, 09544089241247454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Singh, H. Multi-objective optimization of fused deposition modeling for mechanical properties of biopolymer parts using the Grey-Taguchi method. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2023, 36, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotti, A.; Paduano, T.; Napolitano, F.; Zuppolini, S.; Zarrelli, M.; Borriello, A. Fused deposition modeling of polymer composites: Development, properties and applications. Polymers 2025, 17, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, K.I.; Yap, T.C.; Ahmed, R. 3D-printed fiber-reinforced polymer composites by fused deposition modelling (FDM): Fiber length and fiber implementation techniques. Polymers 2022, 14, 4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepenekci, M.; Gharehpapagh, B.; Yaman, U.; Özerinç, S. Mechanical performance of carbon fiber-reinforced polymer cellular structures manufactured via fused filament fabrication. Polym. Compos. 2023, 44, 4654–4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, C.R.; Katyayn, A., Sharma; Chaudhary, N.K. Optimization of Mechanical Properties in Carbon Fiber-Reinforced ABS Composites Fabricated via Fused Filament Fabrication: An Experimental and AI-Based Predictive Approach. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025, 34, 28518–28531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skorda, S.; Bardakas, A.; Segkos, A.; Chouchoumi, N.; Hourdakis, E.; Vekinis, G.; Tsamis, C. Influence of SiC Doping on the Mechanical, Electrical, and Optical Properties of 3D-Printed PLA. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.-L.; Zhang, H.; Yao, S.-S.; Park, S.-J. Effect of Surface Modification on Impact Strength and Flexural Strength of Poly(Lactic Acid)/Silicon Carbide Nanocomposites. Macromol. Res. 2018, 26, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | SiC–PLA | PLA |

|---|---|---|

| Extruder Temperature, °C | 220 | 210 |

| Bed Temperature, °C | 55 | 55 |

| Print Speed, mm/s | 70 | 70 |

| Layer Height, mm | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Nozzle Diameter, mm | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Nozzle Material | WS2 Coated Steel | Brass |

| Geometry (50% infill) | Hexagonal | Hexagonal |

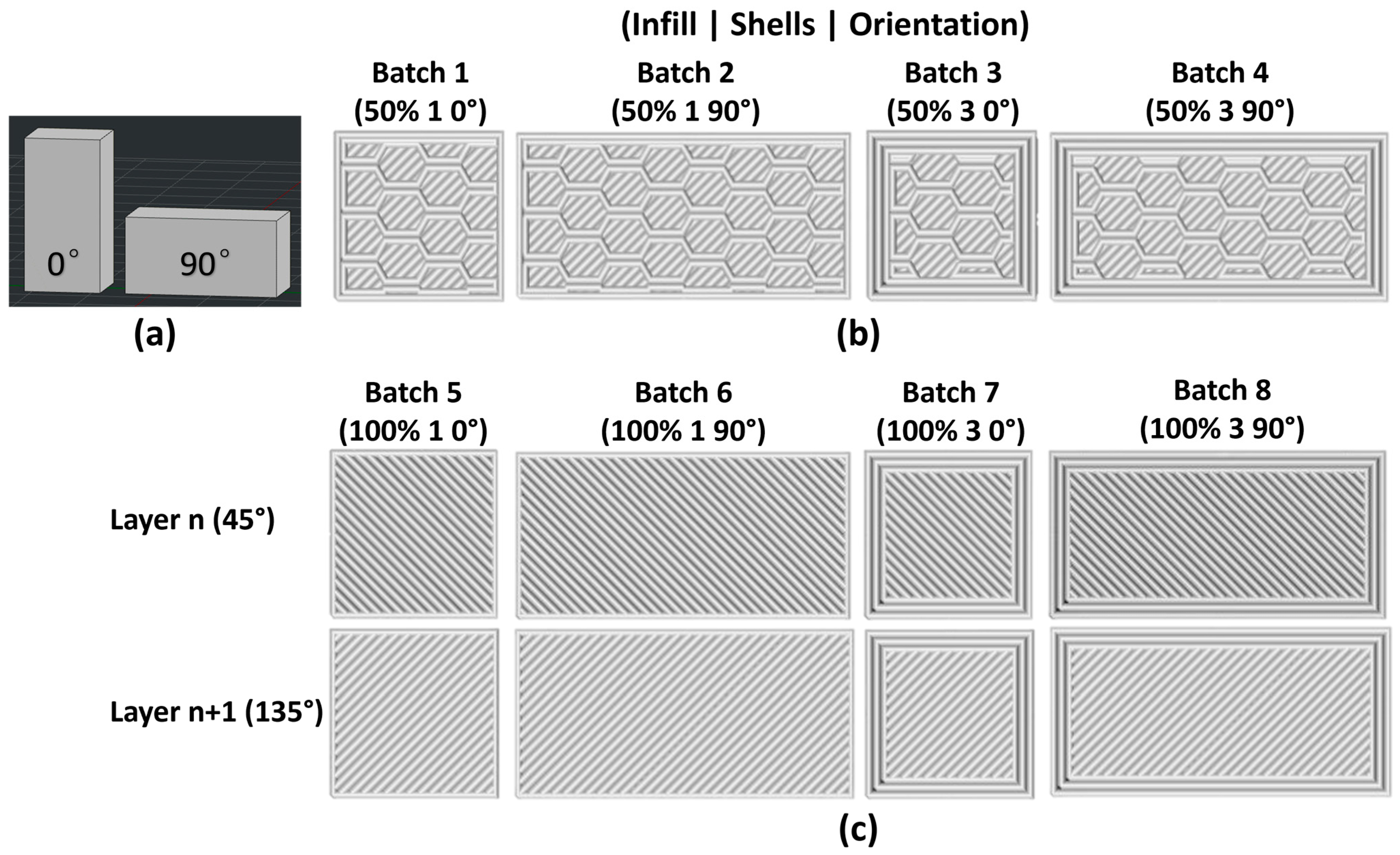

| Batch | Infill % | Shells | Print Orientation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50% | 1 | 0° |

| 2 | 50% | 1 | 90° |

| 3 | 50% | 3 | 0° |

| 4 | 50% | 3 | 90° |

| 5 | 100% | 1 | 0° |

| 6 | 100% | 1 | 90° |

| 7 | 100% | 3 | 0° |

| 8 | 100% | 3 | 90° |

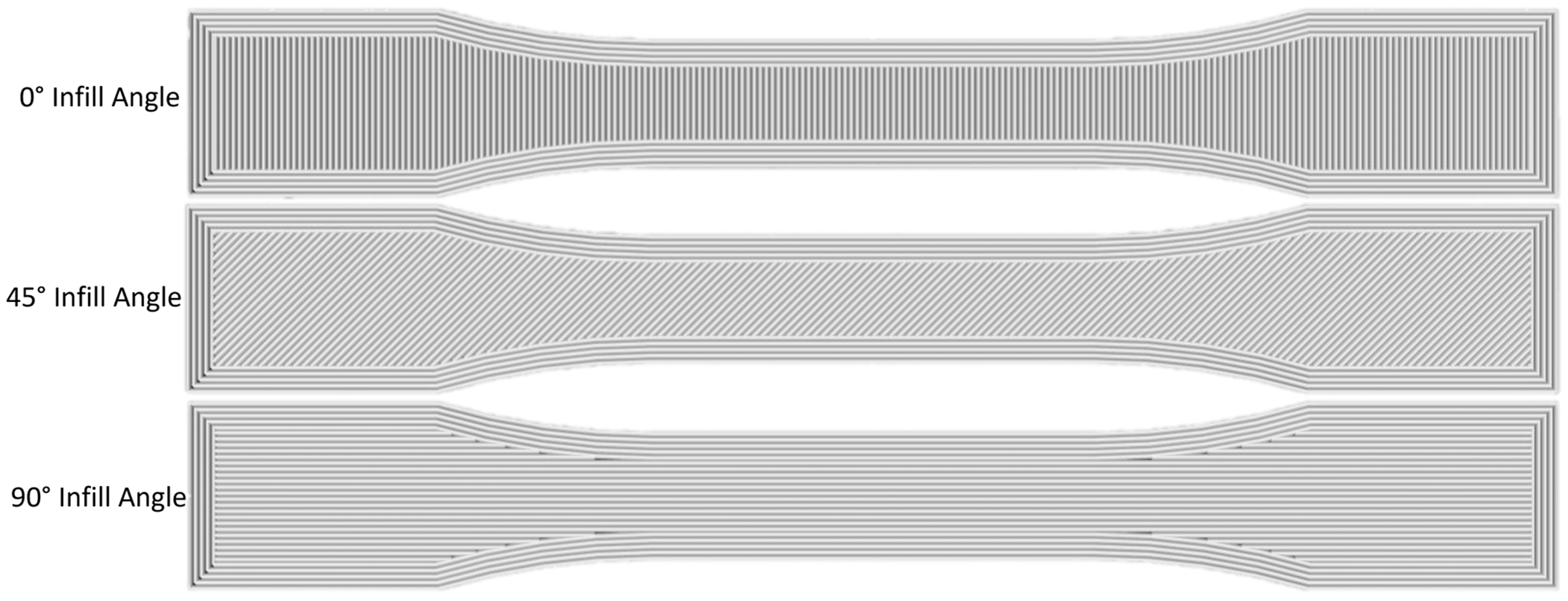

| Batch | Infill Angle [°] | Shells | Layer Height [mm] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 5 | 0.3 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 0.3 |

| 3 | 90 | 5 | 0.3 |

| 4 | 90 | 1 | 0.3 |

| 5 | 45 | 3 | 0.2 |

| 6 | 0 | 5 | 0.1 |

| 7 | 0 | 1 | 0.1 |

| 8 | 90 | 5 | 0.1 |

| 9 | 90 | 1 | 0.1 |

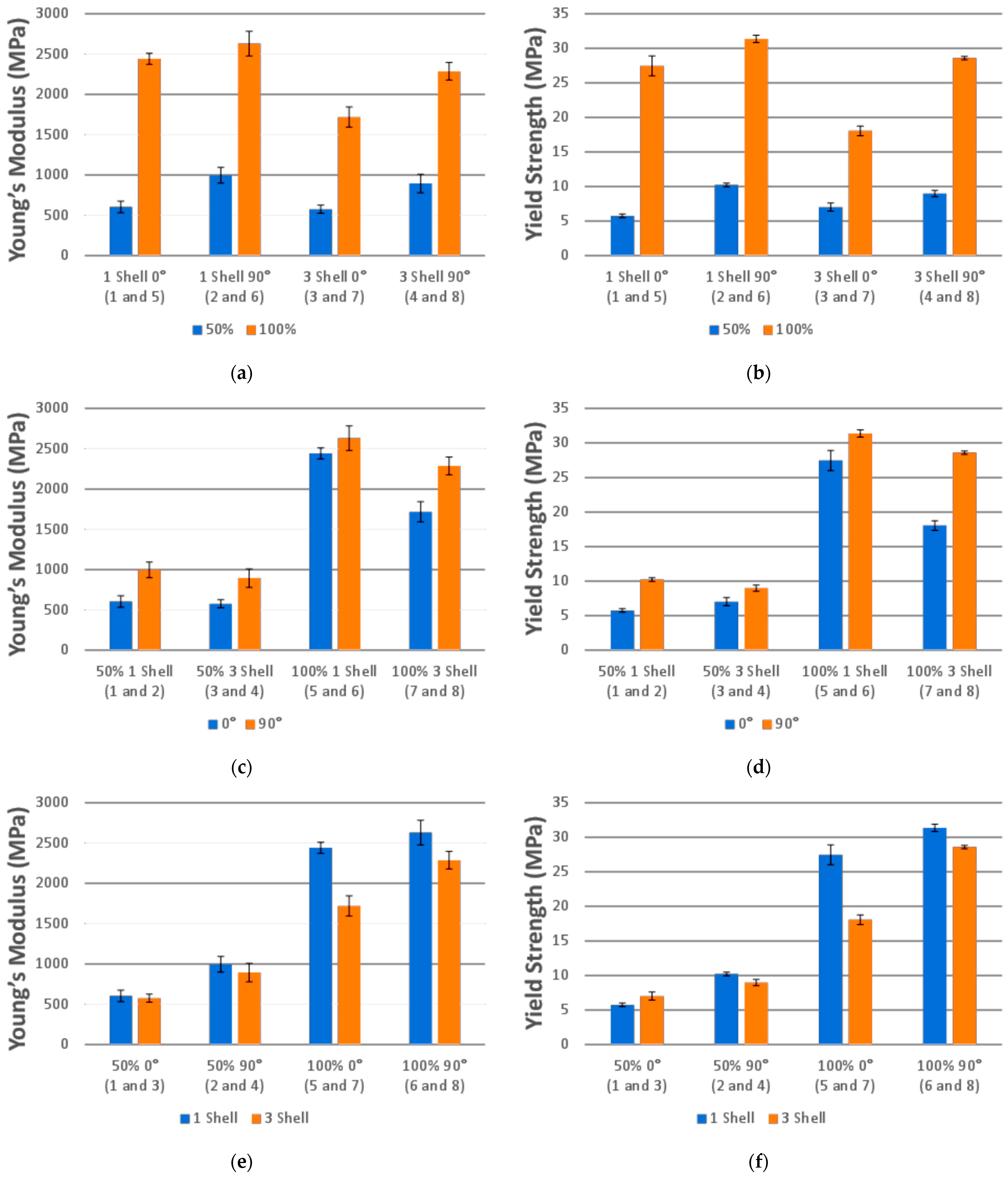

| Batch | Parameters (I, S, O) 1 | Mass (g) | Young’s Modulus (MPa) | Yield Strength (MPa) | Ult. Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50%, 1, 0° | 3.51 ± 0.01 | 604 ± 73 | 5.73 ± 0.26 | 17.21 ± 0.39 |

| 2 | 50%, 1, 90° | 3.71 ± 0.05 | 995 ± 98 | 10.21 ± 0.25 | 12.49 ± 0.19 |

| 3 | 50%, 3, 0° | 4.52 ± 0.02 | 576 ± 50 | 7.01 ± 0.58 | 21.97 ± 1.08 |

| 4 | 50%, 3, 90° | 4.42 ± 0.01 | 894 ± 114 | 8.97 ± 0.46 | 11.20 ± 0.37 |

| 5 | 100%, 1, 0° | 7.95 ± 0.03 | 2443 ± 69 | 27.48 ± 1.44 | 63.90 ± 0.94 |

| 6 | 100%, 1, 90° | 7.96 ± 0.02 | 2629 ± 152 | 31.35 ± 0.54 | 48.24 ± 0.43 |

| 7 | 100%, 3, 0° | 6.99 ± 0.01 | 1719 ± 124 | 18.04 ± 0.70 | 51.27 ± 0.41 |

| 8 | 100%, 3, 90° | 7.50 ± 0.01 | 2287 ± 110 | 28.54 ± 0.26 | 42.90 ± 0.70 |

| Batch | Parameters (I, S, O) 1 | Mass (g) | Young’s Modulus (MPa) | Yield Strength (MPa) | Ult. Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50%, 1, 0° | 2.78 ± 0.00 | 1150 ± 55 | 23.16 ± 0.67 | N/A |

| 2 | 50%, 1, 90° | 2.80 ± 0.05 | 1031 ± 40 | 20.99 ± 1.34 | N/A |

| 3 | 50%, 3, 0° | 3.57 ± 0.00 | 1715 ± 49 | 37.53 ± 1.16 | N/A |

| 4 | 50%, 3, 90° | 3.37 ± 0.00 | 1447 ± 34 | 29.09 ± 0.52 | N/A |

| 5 | 100%, 1, 0° | 4.77 ± 0.00 | 2612 ± 128 | 62.19 ± 2.90 | N/A |

| 6 | 100%, 1, 90° | 4.70 ± 0.00 | 2446 ± 69 | 47.55 ± 0.96 | N/A |

| 7 | 100%, 3, 0° | 4.72 ± 0.01 | 2582 ± 79 | 63.05 ± 1.78 | N/A |

| 8 | 100%, 3, 90° | 4.70 ± 0.00 | 2483 ± 40 | 49.28 ± 0.38 | N/A |

| Batch | Parameters (IA, S, LH) 1 | Mass (g) | Young’s Modulus (MPa) | Yield Strength (MPa) | Ult. Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0°, 5, 0.3 | 16.12 ± 0.04 | 2285 ± 135 | 11.87 ± 0.21 | 12.54 ± 0.39 |

| 2 | 0°, 1, 0.3 | 16.66 ± 0.06 | 2415 ± 315 | 12.96 ± 0.13 | 13.72 ± 0.33 |

| 3 | 90°, 5, 0.3 | 16.68 ± 0.80 | 2541 ± 220 | 12.06 ± 0.74 | 12.86 ± 0.73 |

| 4 | 90°, 1, 0.3 | 16.92 ± 0.10 | 2480 ± 157 | 12.83 ± 0.79 | 13.48 ± 0.87 |

| 5 | 45°, 3, 0.2 | 16.96 ± 0.03 | 3000 ± 428 | 13.35 ± 1.02 | 14.48 ± 1.07 |

| 6 | 0°, 5, 0.1 | 16.29 ± 0.39 | 2763 ± 236 | 13.11 ± 0.64 | 14.33 ± 0.46 |

| 7 | 0°, 1, 0.1 | 16.50 ± 0.48 | 2668 ± 312 | 13.51 ± 0.84 | 14.64 ± 0.14 |

| 8 | 90°, 5, 0.1 | 15.67 ± 0.05 | 2817 ± 129 | 13.70 ± 0.74 | 15.43 ± 0.71 |

| 9 | 90°, 1, 0.1 | 16.66 ± 0.02 | 3200 ± 101 | 15.56 ± 0.47 | 18.06 ± 0.49 |

| Batch | Parameters (IA, S, LH) 1 | Mass (g) | Young’s Modulus (MPa) | Yield Strength (MPa) | Ult. Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0°, 5, 0.3 | 10.13 ± 0.01 | 2091 ± 253 | 30.88 ± 8.55 | 45.42 ± 0.08 |

| 2 | 0°, 1, 0.3 | 10.12 ± 0.01 | 2091 ± 13 | 29.38 ± 0.54 | 34.92 ± 0.42 |

| 3 | 90°, 5, 0.3 | 10.37 ± 0.01 | 1998 ± 192 | 43.80 ± 0.57 | 52.63 ± 0.47 |

| 4 | 90°, 1, 0.3 | 10.42 ± 0.01 | 2114 ± 87 | 30.90 ± 6.29 | 51.78 ± 0.70 |

| 5 | 45°, 3, 0.2 | 10.14 ± 0.00 | 1966 ± 9 | 32.33 ± 3.23 | 43.62 ± 0.32 |

| 6 | 0°, 5, 0.1 | 10.51 ± 0.01 | 2162 ± 41 | 31.11 ± 3.70 | 45.23 ± 0.44 |

| 7 | 0°, 1, 0.1 | 10.60 ± 0.04 | 1821 ± 37 | 25.09 ± 1.33 | 27.03 ± 4.04 |

| 8 | 90°, 5, 0.1 | 10.44 ± 0.01 | 1960 ± 97 | 44.42 ± 0.61 | 54.43 ± 0.45 |

| 9 | 90°, 1, 0.1 | 10.46 ± 0.01 | 2251 ± 220 | 36.42 ± 8.72 | 53.40 ± 0.70 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gyekenyesi, A.P.; Ranaiefar, M.; Halbig, M.C.; Singh, M. Design of Experiments Methodology for Fused Filament Fabrication of Silicon-Carbide-Particulate-Reinforced Polylactic Acid Composites. Macromol 2025, 5, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/macromol5040060

Gyekenyesi AP, Ranaiefar M, Halbig MC, Singh M. Design of Experiments Methodology for Fused Filament Fabrication of Silicon-Carbide-Particulate-Reinforced Polylactic Acid Composites. Macromol. 2025; 5(4):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/macromol5040060

Chicago/Turabian StyleGyekenyesi, Andrew P., Meelad Ranaiefar, Michael C. Halbig, and Mrityunjay Singh. 2025. "Design of Experiments Methodology for Fused Filament Fabrication of Silicon-Carbide-Particulate-Reinforced Polylactic Acid Composites" Macromol 5, no. 4: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/macromol5040060

APA StyleGyekenyesi, A. P., Ranaiefar, M., Halbig, M. C., & Singh, M. (2025). Design of Experiments Methodology for Fused Filament Fabrication of Silicon-Carbide-Particulate-Reinforced Polylactic Acid Composites. Macromol, 5(4), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/macromol5040060