Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) Produced from Food-Related Wastes: Solid-State NMR Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Solid-State NMR Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

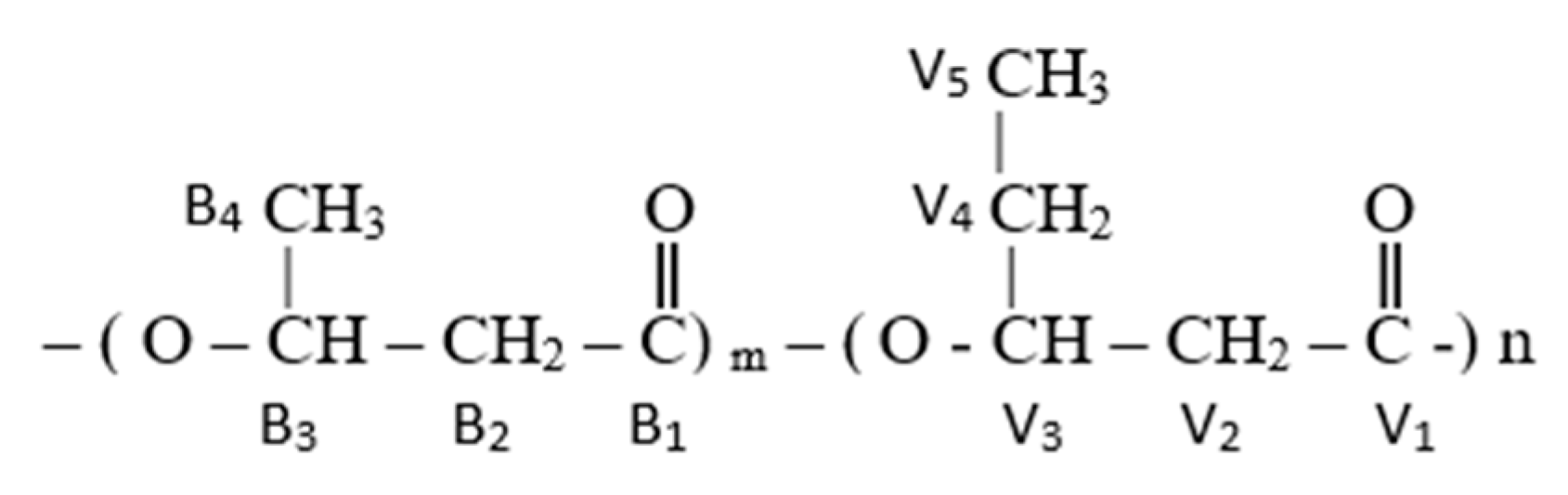

3.1. Copolymer Composition

3.2. 13C Shifts Due to Crystal Lattice

3.3. Crystallinity

3.4. Mobility and Heterogeneity from Relaxation Times

3.5. Comparison with Prior Work

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Atarés, L.; Chiralt, A.; González-Martínez, C. Production of Polyhydroxyalkanoates for Biodegradable Food Packaging Applications Using Haloferax mediterranei and Agrifood Wastes. Foods 2024, 13, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.-Q.; Patel, M.K. Plastics Derived from Biological Sources: Present and Future: A Technical and Environmental Review. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 2082–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.Y.; Lim, S.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Son, J.; Choi, J.-I.; Park, S.J. Microbial production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate), from lab to the shelf: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 274, 133157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Briso, A.L.; Serrano-Aroca, A. Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-co-3-Hydroxyvalerate): Enhancement Strategies for Advanced Applications. Polymers 2018, 10, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Deng, B.; Zhao, X. Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) and Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate): Structure, Property, and Fiber. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2014, 2014, 374368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, K.; Geppi, M. Solid State NMR: Principles, Methods, and Applications; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.N.; Asakura, T.; English, A.D. (Eds.) NMR Spectroscopy of Polymers: Innovative Strategies for Complex Macromolecules; ACS Symposium Series, Number 1077; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cali, J.; Hu, W.; Kysor, E.; Kohlmann, O. Aging of polypropylene random copolymers studied by NMR relaxometry. Polymer 2021, 230, 124102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, V.; van Erp, T.B.; Balzano, L.; Gahleitner, M.; Parkinson, M.; Govaert, L.E.; Litvinov, V.; Kentgens, A.P.M. The chemical structure of the amorphous phase of propylene–ethylene random copolymers in relation to their stress–strain properties. Polymer 2014, 55, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E.W.; Kristiansen, P.E.; Pedersen, B. Crystallinity of Polyethylene Derived from Solid-State Proton NMR Free Induction Decay. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 5444–5450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamaru, R.; Horii, F.; Murayama, K. Phase structure of lamellar crystalline polyethylene by solid-state high-resolution carbon-13 NMR detection of the crystalline-amorphous interphase. Macromolecules 1986, 19, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, Y.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Kunioka, M. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Studies of Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) and Polyphosphate Metabolism in Alcaligenes eutrophus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1989, 55, 2932–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, N.; Sakurai, M.; Inoue, Y.; Chujo, R.; Doi, Y. Studies of cocrystallization of poly(3 -hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) by solid state high resolution 13C NMR spectroscopy and differential scanning calorimetry. Macromolecules 1991, 24, 2178–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, F.G.; Marchessault, R.H. Solid-State 13C NMR Study of the Molecular Dynamics in Amorphous and Crystalline Poly(β-hydroxyalkanoates). Macromolecules 1992, 25, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyro, A.; Marchessault, R.H. Carbon-13 Nuclear Magnetic Relaxation Measurements of Poly(4-hydroxybutyrate) and Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-4-Hydroxyvalerate) in the bulk. Macromolecules 1995, 28, 6108–6111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y. Solid-state structure and properties of bacterial copolyesters. J. Mol. Struct. 1998, 441, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitomo, H.; Doi, Y. Lamellar thickening and cocrystallization of poly(hydroxyalkanoate)s on annealing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 1999, 25, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yamada, S.; Asakawa, N.; Yamane, T.; Yoshie, N.; Inoue, Y. Comonomer Compositional Distribution and Thermal and Characterization of Bacterial Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate)s with High 3-Hydroxyvalerate Content. Biomacromol. 2001, 2, 1315–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshie, N.; Saito, M.; Inoue, Y. Structural Transition of Lamella Crystals in a Isomorphous Copolyester, Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate). Macromolecules 2001, 34, 8953–8960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, G.; Chen, Q. Solid-state NMR study on the structure and mobility of the non-crystalline region of poly(3-hydroxybutyrae) and Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate). Polymer 2002, 43, 2095–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tang, H.; Hou, G.; Shen, Y.; Deng, F. The domain structure and mobility of semi-crystalline poly(3-hydroxybutyrae) and Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate): A solid state NMR study. Polymer 2007, 48, 2928–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuma, H.S.; Sabita, A.; Putri, N.A.; Azliza, N.; Illiyanasafa, N.; Darmokoesoemo, H.; Amenaghawon, A.N.; Kurniawan, T.A. Waste to wealth: Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) production from food waste for a sustainable packaging paradigm. Food Chem. Mol. Sci. 2024, 9, 100225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, C.; Rahman, A.; Rehman, A.U.; Walsh, M.K.; Miller, C.D. Food waste conversion to microbial polyhydroxyalkanoates. Microb. Biotechnol. 2017, 10, 1338–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Täuber, S.; Riedel, S.L.; Junne, S. Polyhydroxyalkanoate production from food residues. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 109, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriaga, M.; Pinar, F.J.; Izarra, I.; del Amo, J.; Vicente, J.; Fernández-Morales, F.J.; Mena, J. Valorization of Agri-Food Waste into PHA and Bioplastics: From Waste Selection to Transformation. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melendez-Rodriguez, B.; Castro-Mayorga, J.L.; Reis, M.A.M.; Sammon, C.; Cabedo, L.; Torres-Giner, S.; Lagaron, J.M. Preparation and characterization of electrospun food biopackaging films of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) derived from fruit pulp biowaste. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 2, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentino, F.; Moretto, G.; Lorini, L.; Bolzonella, D.; Pavan, P.; Majone, M. Pilot-Scale polyhydroxyalkanoate production from combined treatment of organic fraction of municipal solid waste and sewage sludge. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 12149–12158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Lopez, K.J.; Torres-Giner, S.; Enescu, D.; Cabedo, L.; Cerqueira, M.A.; Pastrana, L.M.; Lagaron, J.M. Electrospun active biopapers of food waste derived poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) with short-term and long-term antimicrobial performance. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melendez-Rodriguez, B.; Torres-Giner, S.; Lorini, L.; Valentino, F.; Sammon, C.; Cabedo, L.; Lagaron, J.M. Valorization of Municipal Biowaste into Electrospun Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) Biopapers for Food Packaging Applications. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 6110–6123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melendez-Rodriguez, B.; Reis, M.A.M.; Carvalheira, M.; Sammon, C.; Cabedo, L.; Torres-Giner, S.; Lagaron, J.M. Development and Characterization of Electrospun Biopapers of Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) Derived from Cheese Whey with Varying 3-Hydroxyvalerate. Biomacromolecules 2021, 22, 2935–2953. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.N.; Biswas, A.; Vermillion, K.; Melendez-Rodriguez, B.; Lagaron, J.M. NMR Analysis and Triad Sequence Distributions of Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate). Polym. Test. 2020, 90, 106754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanham, A.B.; Ricardo, A.R.; Albuquerque, M.G.E.; Pardelha, F.; Carvalheira, M.; Coma, M.; Fradinho, J.; Carvalho, G.; Oehmen, A.; Reis, M.A.M. Determination of the extraction kinetics for the quantification of polyhydroxyalkanoate monomers in mixed microbial systems. Process Biochem. 2013, 48, 1626–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melendez-Rodriguez, B.; Lagaron, J.M. (Novel Materials and Nanotechnology Group, IATA, CSIC, Paterna, Spain). Private communication, 2020.

- Cheng, H.N.; Klasson, K.T.; Wartelle, L.; Edwards, J.C. Solid state NMR and ESR studies of activated carbon produced from pecan shells. Carbon 2010, 48, 2455–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Hu, W.; Russell, T.P. Measuring the Degree of Crystallinity in Semicrystalline Regioregular Poly(3-hexylthiophene). Macromolecules 2016, 49, 4501–4509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantzsch, V.; Haas, M.; Ozen, M.B.; Ratzsch, K.-F.; Riazi, K.; Kauffmann-Weiss, S.; Palacios, J.K.; Müller, A.J.; Vittorias, I.; Guthausen, G.; et al. Polymer crystallinity and crystallization kinetics via benchtop 1H NMR relaxometry: Revisited method, data analysis, and experiments on common polymers. Polymer 2018, 145, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunioka, M.; Tamaki, A.; Doi, Y. Crystalline and Thermal Properties of Bacterial Copolyesters: Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) and Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-4-hydroxybutyrate). Macromolecules 1989, 22, 694–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Source | Expected HV | Obsd HV, Sol. NMR | Obsd HV, CP-MAS | Obsd HV, SPE-MAS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PHBV commercial | 2–3 | 1 | - | ~2 |

| 2 | Municipal wastewater | 10 | 10 | 7 | - |

| 3 | Fruit residues | 20 | 15 | 12 | 18 |

| 4 | Municipal wastewater residuals | 20 | 23 | 10 | 23 |

| 5 | Cheese whey | 20 | 15 | 11 | 13 |

| 6 | Cheese whey | 27 | 19 | 14 | - |

| 7 | Cheese whey | 40 | 40 | 31 | - |

| 8 | Cheese whey | 60 | 60 | 50 | 59 |

| No. | % HV (Nominal) | CP-MAS | SPE-MAS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crystalline | Amorphous | Crystalline | Amorphous | ||

| 1 | 2–3 | 71 | 29 | 72 | 28 |

| 2 | 10 | 78 | 22 | - | - |

| 3 | 20 | 74 | 26 | 76 | 24 |

| 4 | 20 | 70 | 30 | 68 | 32 |

| 5 | 20 | 78 | 22 | 66 | 34 |

| 6 | 27 | 80 | 20 | - | - |

| 7 | 40 | 77 | 23 | - | - |

| 8 | 60 | 80 | 20 | - | - |

| Average | 76.0 | 24.0 | 70.5 | 29.5 | |

| 1H-SP-Static NMR | Component % | Component LWHH (Hz) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Narrow | Medium | Broad | Narrow | Medium | Broad |

| 1. 3% HV commercial | 0.0 | 64.6 | 32.6 | - | 1450 | 5210 |

| 2. 10% HV wastewater | 49.5 | 8.4 | 42.1 | 508 | 1237 | 6520 |

| 3. 20% HV fruit residues | 37.1 | 17.4 | 45.5 | 763 | 1536 | 10,240 |

| 4. 20% HV wastewater residues | 20.6 | 36.8 | 42.7 | 581 | 3973 | 14,908 |

| 5. 20% HV cheese whey | 27.3 | 29.8 | 42.9 | 617 | 2249 | 16,082 |

| 6. 27% HV cheese whey | 38.2 | 28.3 | 33.5 | 657 | 1582 | 9510 |

| 7. 40% HV cheese whey | 41.1 | 21.6 | 37.3 | 521 | 2042 | 6913 |

| 8. 60% HV cheese whey | 45.0 | 29.4 | 25.5 | 570 | 2250 | 9559 |

| Average | 32.4 | 29.5 | 37.8 | 602 | 2040 | 9868 |

| No | Sample | TCH (μs) | T1ρH (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3% HV commercial | 945 | 31.9 |

| 2 | 10% HV wastewater | 1279 | 16.2 |

| 3 | 20% HV fruit residues | 976 | 16.2 |

| 4 | 20% HV wastewater residuals | 1019 | 23.8 |

| 5 | 20% HV cheese whey | 1018 | 16.3 |

| 6 | 27% HV cheese whey | 1059 | 16.4 |

| 7 | 40% HV cheese whey | 865 | 19.6 |

| 8 | 60% HV cheese whey | 983 | 14.8 |

| Average | 1049.3 | 20.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Biswas, A.; Cheng, H.N.; Edwards, J.C. Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) Produced from Food-Related Wastes: Solid-State NMR Analysis. Macromol 2025, 5, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/macromol5040061

Biswas A, Cheng HN, Edwards JC. Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) Produced from Food-Related Wastes: Solid-State NMR Analysis. Macromol. 2025; 5(4):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/macromol5040061

Chicago/Turabian StyleBiswas, Atanu, Huai N. Cheng, and John C. Edwards. 2025. "Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) Produced from Food-Related Wastes: Solid-State NMR Analysis" Macromol 5, no. 4: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/macromol5040061

APA StyleBiswas, A., Cheng, H. N., & Edwards, J. C. (2025). Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) Produced from Food-Related Wastes: Solid-State NMR Analysis. Macromol, 5(4), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/macromol5040061