1. Introduction

The term “wellness” has become a buzzword in the hospitality and tourism industry, promoting a healthy and natural lifestyle that includes engaging in a variety of activities. Specifically, the Global Wellness Institute (GWI) defines wellness as “the active pursuit of activities, choices, and lifestyles that lead to a state of holistic health” (

Global Wellness Institute (GWI), 2025). This means that people incorporate wellness lifestyles and activities in their daily lives. One of the fastest-growing markets in hospitality and tourism is wellness with the pursuit of maintaining or enhancing one’s personal well-being (

Global Wellness Institute (GWI), 2025). For some customers, their choice of accommodation could be motivated by wellness with emphasis on incorporating wellness activities and lifestyles outside of their daily lives, such as during their travels.

As wellness customers are an important market segment, hospitality and tourism providers have increasingly integrated wellness services (WSs) into their offerings, extending beyond traditional spas and fitness centers to include meditation programs, wellness workshops, in-room fitness amenities, healthy dining options, and personalized wellness experiences (

C. G. Chi et al., 2019). Many hotel chain companies, such as Hilton Worldwide, Marriott International, and Wyndham Hotel Group, now have programs specifically targeted on wellness. Some hotels also offer amenities such as providing fitness equipment or yoga mats in guest rooms, healthy menus, fitness concierge services, cooking classes, and others (

Jones, 2024). Furthermore, other hotel brands like InterContinental Hotel Group (IHG) and Hyatt Hotels and Resorts even offer their own unique brands focused on wellness that include IHG’s EVEN Hotels, Six Senses Hotels Resports and Spas and Regent Spa and Wellness and Hyatt’s Miraval Resorts, Exhale, and Zoetry Wellness and Spa Resorts (

Hollander, 2024). With hotels striving to offer WSs to create the environment, they also need to identify their target customers who intend to use these services (

O. H. Chi et al., 2024). By treating wellness as what individuals can do every day to take care of themselves, it is no different during their travels too. As wellness becomes a differentiating factor in accommodation choice, particularly for travelers seeking to maintain or enhance healthy lifestyles while away from home, identifying the characteristics of customers who are most likely to engage with WSs has become a strategic priority for the industry (

O. H. Chi et al., 2024). Therefore, studying certain personality traits, like grit, is an important way to recognize wellness customers.

In psychology, grit is a personality trait that reflects a person’s determination and consistent pursuit of long-term goals. Wellness fundamentally emphasizes personal responsibility and sustained self-regulation (

Joppe, 2010), suggesting that individual differences play a critical role in wellness-related behaviors during travel. One personality trait particularly relevant in this context is grit, defined as perseverance and passion for long-term goals (

A. L. Duckworth et al., 2007). Grit has been identified as a key factor that influences the progression of physical activity (PA) (

Reed et al., 2013). As grit has been associated positively with commitment to engage in physical activities (

Dunston et al., 2022), it seems logical to assume that grit could influence customers’ commitment with wellness activities and motivate them to pursue wellness consistently, even outside of their routine environment. Such persistence may be especially salient in hotel settings, where routines are disrupted and engagement in wellness activities requires intentional effort (

X. Liu et al., 2025).

The transtheoretical model (TTM) that

Prochaska and Velicer (

1997) developed provides a robust theoretical framework for understanding intentional behavioral change through stages of readiness. As personality traits such as grit are associated with persistence and goal achievement, they are relevant to the stages of change described by TTM (

A. L. Duckworth et al., 2007). According to TTM, this progression involves the following five stages: pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. As such, this study applied TTM as a theoretical foundation to explore the role that grit plays in predicting customers’ engagement with WSs in the hospitality industry.

While considerable research has been conducted on grit’s effect on PA, there is limited empirical research on the way in which TTM may influence the utilization of WSs. Further, while WSs are prevalent in the hospitality and tourism industry, people’s motivation or traits to use WSs as part of their engagement behavior during a hotel stay have not been studied thoroughly. Specifically, prior research in the hospitality context has not considered the role of grit in such hotels as an antecedent to WSs. Thus, this study explored grit as the motivation for customers’ wellness behavioral outcomes during their hotel stay based upon TTM theory. This study also evaluated grit’s effect on different types of customer engagement behaviors when they use wellness hospitality services, such as intention to visit (VI), willingness to pay a premium (WPP), and electronic word of mouth (eWOM). Therefore, the purpose of this research was to examine grit’s effect on WSs and future engagement in the hospitality context. The objectives of this study were threefold as follows: first, to evaluate WSs in the hospitality and tourism context; second, to examine the effects of grit and TTM on WSs; and third, to estimate the effects of grit and WSs on customers’ engagement. To address these objectives, the study employed a quantitative design using an online survey of 337 U.S. hotel customers. The data were analyzed through structural equation modeling (SEM), which enabled testing of the proposed hypotheses and validation of the theoretical framework.

By integrating grit and TTM into a unified framework, this study makes several contributions. Theoretically, it extends the wellness and hospitality literature by identifying grit as a critical psychological antecedent of wellness service engagement. Empirically, it offers novel insights into how personality-driven persistence shapes customer engagement behaviors in wellness-oriented hospitality settings. Managerially, the findings provide actionable guidance for hospitality practitioners seeking to identify, target, and retain wellness-oriented customers through more personalized and effective wellness offerings.

1.1. Theoretical Background

1.1.1. The Relationship Between Transtheoretical Model and Grit

This study is grounded in the TTM, a widely recognized framework used to understand intentional behavioral change across biopsychosocial dimensions (

Prochaska & DiClemente, 1984). TTM is particularly useful in capturing the evolving stages that individuals go through as they adopt new health behaviors, which makes it highly relevant when studying wellness-related actions. The model outlines five progressive stages as follows: precontemplation (not ready); contemplation (getting ready); preparation (ready); action; and maintenance, each of which represents a shift in individuals’ cognition, emotions, and behavior as they move toward sustained change (

Prochaska & Velicer, 1997).

Notably,

Reed et al. (

2013) and

Marentes Castillo et al. (

2022) demonstrated a positive correlation between grit and the stages of TTM, in which grit emerged as a critical factor in goal persistence and long-term commitment (

A. L. Duckworth et al., 2007). Grit influences an individual’s ability to persevere through the challenges and setbacks encountered. Integrating grit into TTM provides a nuanced understanding of how personality traits interact with behavioral change processes, which reinforces the important role that grit plays as a motivational factor throughout all stages of the model.

Applying the TTM and grit concepts together to the hospitality and wellness context offers valuable insights into the way that customers might progress through the stages of readiness to engage with WSs during hotel stays. This model has been applied effectively to understand engagement with PA, as the stages of TTM align closely with the intentions to initiate and maintain exercise behaviors. In this context, grit is hypothesized to facilitate movement through the TTM stages, which enhances both the likelihood of adopting and sustaining wellness behaviors. Just as individuals move through TTM stages when they adopt PA, guests in hospitality settings may progress similarly in their engagement with WSs, such as gyms, spas, or mindfulness programs. By understanding the stages of behavioral change, hospitality professionals can adapt wellness offerings to guests’ needs better and enhance their motivation to engage with these services and support their commitment to wellness during travel.

H1. TTM stages and grit influence each other positively in choosing WSs during a hotel stay.

1.1.2. The Effect of Grit on Hospitality Wellness Services

The American doctor Halbert Dunn described the concept of wellness in 1959 (

Mueller & Kaufmann, 2001). Throughout history, individuals have sought wellness. The wellness industry is still one of the fastest-growing and most lucrative segments of the hospitality market (

Okumus & Kelly, 2022). After discovering the expanded market circumstances, the hospitality and tourism industry has increased its WSs in response to the wellness demand. To understand the WSs in the hospitality industry better, this study classified WSs into three categories as follows: “Hospital”ity services (HSs); physical fitness services (PF); and enhanced hygiene standards (EHSs).

Although all wellness services can be considered part of the broader hospitality experience, this study classified them into three distinct categories to provide analytical clarity. The term “Hospital”ity is used in this study to capture the convergence of hospital-like attributes within hotels, reflecting the growing emphasis on customer health and wellness. Hospitals and hotels share many fundamental features, such as the provision of comfort, safety, and care (

Zygourakis et al., 2014). Prior studies have examined the incorporation of hospitality elements into hospitals to improve patient well-being (

Suess & Mody, 2017;

Zygourakis et al., 2014), while hotels are increasingly adopting hospital-inspired services to enhance customer satisfaction and wellness. Examples of “Hospital”ity services include aroma therapy, mood lighting, healthcare staff availability, smart-room technology, air filtration, thermal comfort, and healthy bedding. The second category, PF, encompasses traditional wellness amenities that directly support physical activity and relaxation, including spas, saunas, meditation programs, yoga, and fitness studios. Finally, the third category, EHS, emerged in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and represents heightened safety and sanitation measures, such as hospital-grade sanitizers, touchless kiosks, sterilizing wipes, and mandatory face coverings. By distinguishing these three categories, the study highlights the multifaceted nature of wellness services in hotels. This classification allows for a more nuanced understanding of how different types of services contribute to customer engagement, while still recognizing that all of them collectively fall under the umbrella of hospitality wellness services.

Wellness customers are proactive in seeking ways to maintain their health and wellness more through voluntary non-medical activities, such as engaging in physical and wellness activities. Long-term goals are achieved through perseverance and passion, which is the definition of grit (

A. L. Duckworth et al., 2007). Gritty individuals tend to persevere in completing challenging goals by overcoming obstacles and setbacks (

A. Duckworth & Gross, 2014). Grit has been associated widely with educational, physical, and professional achievements (

A. L. Duckworth & Quinn, 2009) and is recognized as a determinant of health-promoting behaviors, including wellness. In particular, studies have shown that grit is correlated positively with engaging in moderate-to-vigorous PA and plays an essential role in maintaining motivation across different stages of exercise intensity and thereby acts as a substantial predictor of PA engagement (

Hein et al., 2019;

Reed et al., 2013). Findings also suggest that grit may serve as a protective factor for college students, promoting more adaptive coping strategies and supporting positive health behaviors by mitigating the impact of stress on depressive symptoms (

Amrani, 2019). In addition,

Rutberg et al. (

2020) demonstrated that grit affects PA, motivation, meaningfulness, and goal setting, which highlighted its role in fostering sustained, positive health behaviors.

Although grit is a relatively new concept in the hospitality and tourism literature, its relevance is clear, as hotels provide wellness-oriented services increasingly to meet consumers’ greater demand for health and wellness options during travel. Gritty individuals who prioritize wellness may seek out hotels with WSs as part of their efforts to maintain healthy routines, even when away from home.

Cosgrove et al. (

2018) noted grit’s potential to influence customer loyalty and repeat engagement in hospitality and tourism settings, which suggests that grit could play a key role in predicting guests’ engagement with wellness amenities. For example, in sport-specific contexts,

Larkin et al. (

2016) found that gritty soccer players devoted more time to practice, competition, and related activities. These findings indicate that grit’s influence on wellness behaviors extends into hospitality, where guests with high grit may be drawn particularly to WSs as part of their ongoing commitment to health. The literature review above indicates that grit can be a factor that influences the intention to use WSs during a hotel stay. Consequently, grit with respect to TTM can be a determining factor in choosing WSs during a hotel stay.

H2a. Grit has a positive influence on HS.

H2b. Grit has a positive influence on PF.

H2c. Grit has a positive influence on EHS.

1.1.3. The Effect of WSs on Customer Engagement in the Form of Behavioral Intentions

While the pivotal point of hospitality and tourism research is to determine both customers’ and providers’ perceptions, customers’ engagement has considerable effects on service performance. This study evaluated customers’ engagement from the standpoint of their behavioral intention. Customer engagement is a well-established criterion in hospitality marketing and has proven to be a beneficial outcome for hospitality providers (

H. Choi & Kandampully, 2019). Thus, it is not surprising that many people are turning to a venue that provides WSs to improve their performance and productivity (

Chang, 2024;

Goetzel & Ozminkowski, 2008). The inclusion of WS in a hotel is related positively to desired outcomes of behavioral intention (

C. G. Chi et al., 2019). As

Van Doorn et al. (

2010) stated that the behavioral aspect of customer engagement has attracted more attention, this study focused on the behavioral aspects of customer engagement, which include VI, eWOM, and WPP.

Grit, defined as perseverance and passion for long-term goals (

A. L. Duckworth et al., 2007), may strengthen these behavioral outcomes by fostering consistency in wellness-related choices. Customers high in grit are more likely to exhibit repeat visit intentions, as they persistently pursue health-related goals through wellness-friendly hospitality services. Recent consumer research further supports this argument, showing that gritty individuals make more goal-congruent consumption decisions, for instance, choosing healthier over indulgent foods, because they perceive such decisions as advancing their long-term objectives (

Wright & Schultz, 2022). This suggests that in a hospitality and tourism context, grit can drive customers to favor wellness services, revisit venues that provide them, and endorse these offerings both financially and socially. Moreover, their tendency to remain committed over time can encourage stronger eWOM behaviors and greater willingness to pay a premium for services that align with their enduring wellness values (

Jachimowicz et al., 2018). This study seeks to establish a relationship between wellness services and behavioral outcomes, including visit intention, willingness to pay a premium, and eWOM. These behavioral outcomes ensure the customers’ participation and service providers’ satisfaction.

1.1.4. Visit Intention

Customers’ visit intention refers to their willingness to visit a hotel where their needs and preferences are fulfilled (

M. F. Chen & Tung, 2014). In line with the growing inclusion of WSs in tourism destinations, research has shown that wellness offerings increase tourists’ intention to visit such places (

C. G. Chi et al., 2019;

Majeed & Gon Kim, 2023;

Hall et al., 2011). For instance,

Hall et al. (

2011) found that wellness amenities, including spa and fitness services, positively influenced tourists’ revisit intentions and overall satisfaction. Similarly,

Zopiatis et al. (

2017) and

O. H. Chi et al. (

2024) reported that hotels providing tailored wellness programs were more likely to attract health-conscious and physically active guests. These findings indicate that hotels incorporating wellness services can better meet the expectations of customers with a health-oriented lifestyle, thereby enhancing their intention to visit.

Gan et al. (

2023) demonstrated that health and wellness tourists’ motivation significantly positively predicts their behavior intentions. Travelers’ perceived value of health and wellness tourism significantly partially mediates the associations between their behavioral intention and various motivations, including escape, attraction, environmental, and interpersonal motivations.

Seow et al. (

2024) found that tourists’ satisfaction and experience in wellness tourism positively influence their revisit intention, highlighting the importance of wellness services in attracting repeat visitors.

K. H. Chen et al. (

2023) identified four factors of spa hotel experiences—health promotion treats, mental learning, unique travel experience, and healthy diet—that influence revisit intention. These factors underscore the role of wellness services in enhancing customers’ intention to revisit wellness tourism destinations.

Given that grit reflects perseverance and goal-oriented behavior (

A. L. Duckworth et al., 2007), it is reasonable to assume that customers high in grit are more likely to seek out and repeatedly visit hotels offering wellness services, as these venues align with their long-term health and wellness goals.

H3a. HS has a positive influence on customers’ intention to visit hotels that offer WSs.

H4a. PFs have a positive influence on customers’ intention to visit hotels that offer WSs.

H5a. EHS has a positive influence on customers’ intention to visit hotels that offer WSs.

H6a. Grit is related positively to customers’ intention to visit hotels that offer WSs.

1.1.5. Willingness to Pay a Premium

Willingness to pay a premium is a purchasing behavior in which the customer is willing to pay a premium price for a particular product or service. This willingness is a consequent behavior in customers’ engagement with a company or brand (

Risitano et al., 2017). A product or service’s perceived value and exclusivity are some of the determinants that encourage customers to pay a premium (

Risitano et al., 2017). While environmentally friendly customers are willing to pay a premium for green restaurants (

Namkung & Jang, 2017) and green hotels (

Kuminoff et al., 2010), similarly, wellness customers tend to comprise more wealthy, educated, and well-traveled customers who are likely to spend more than the average customers (

Okumus & Kelly, 2022). In 2023, international wellness tourists spent 41% more than the average international tourist, while domestic wellness tourists spent 175% more than the average domestic tourist (

Global Wellness Institute (GWI), 2025). While grit is expected to affect the intention to use WSs in hotels, wellness customers are keen on trying new wellness experiences and are likely to pay more for them.

H3b. HS has a positive influence on customers’ willingness to pay a premium for hotels that offer WSs.

H4b. PFs have a positive influence on customers’ willingness to pay a premium for hotels that offer WSs.

H5b. EHS has a positive influence on customers’ willingness to pay a premium for hotels that offer WSs.

H6b. Grit is related positively to customers’ willingness to pay a premium for hotels that offer WSs.

1.1.6. eWOM

Word of Mouth (WOM) serves as an important source of interpersonal information to predict a product or service’s reliability and performance (

Pourfakhimi et al., 2018). Among the several types of WOM, eWOM has been found to be influential in decision-making when purchasing a product or service online (

Flanagin et al., 2014). The availability of internet connections and the increase in social media interest have made eWOM widespread among customers. Further,

Flanagin et al. (

2014) found that customers tend to rely on web-based information compared to other sources of information. eWOM helps customers and service providers create and enhance trust and offers new capacity by providing standards to customers’ behavioral intentions (

Flanagin et al., 2014).

H. Choi and Kandampully (

2019) found a significantly positive relation between WOM and customer satisfaction. Perceived values of WSs at a hotel may be correlated positively with the purchase intention and eWOM for potential wellness customers.

This study hypothesized that grit leads customers to use WS at a hotel, and thus, it is logical to assume that grit will lead them to engage in eWOM behavior to promote WSs. Specific to wellness services, research shows that eWOM engagement is shaped by multiple psychological and experiential factors. For example, a recent study identified drivers of eWOM among wellness customers, including service experience, gratitude, moral obligation, trust, altruism, hedonic value, and self-enhancement (

Tariyal et al., 2023), all of which share meaningful connections with grit (

Millonado Valdez & Daep Datu, 2021;

Song et al., 2025;

Steinke, 2014). These findings underscore that eWOM in wellness contexts is not only transactional but also shaped by relational and affective factors, which suggests that grit-driven wellness customers may be particularly motivated to engage in eWOM to express meaningful experiences and encourage others to participate.

H3c. HS has a positive influence on customers’ eWOM activity for the hotels that offer WSs.

H4c. PF have a positive influence on customers’ eWOM activity for the hotels that offer WSs.

H5c. EHS has a positive influence on customers’ eWOM activity for the hotels that offer WSs.

H6c. Grit is related positively to customers’ eWOM activity for the hotels that offer WSs.

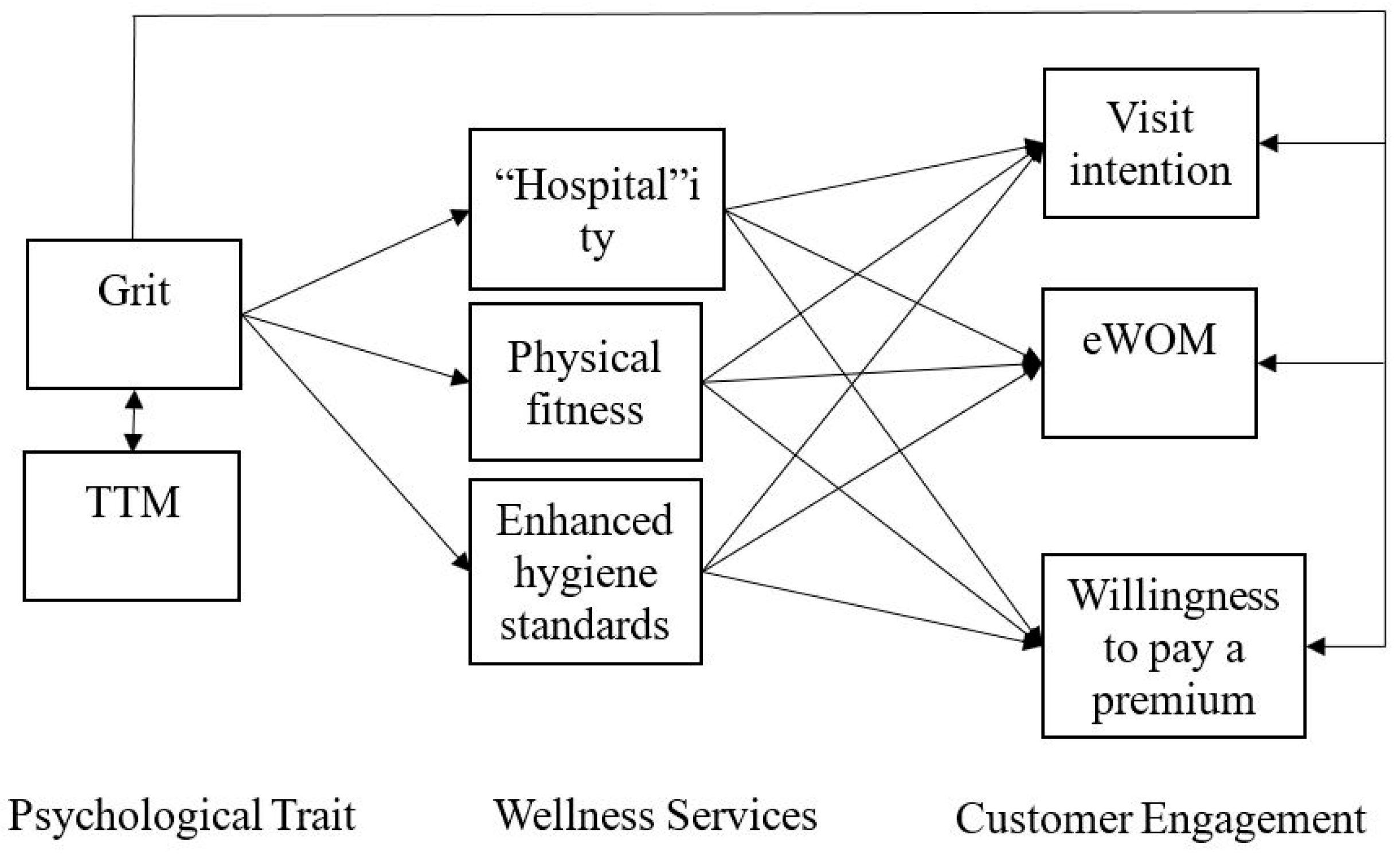

Figure 1 shows the relation between the variables mentioned in the hypotheses.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

The 337 participants’ socio-demographic profiles are shown in

Table 1. Of those, 176 (52.2%) were male and 156 (46.3%) were female. Nearly half of the respondents (

n = 164, 48.7%) were 18–30 years old, 104 (30.9%) were 31–40 years old, and 37 (11%) were 41–50 years old. Most of the respondents (68.5%) were Caucasian, while 50 (14.8%) were Asian. More than half of the participants were not married (

n = 199, 59.1%). With respect to employment status, more than half of them worked full-time (

n = 199, 59.1%), followed by part-time (

n = 59, 17.5%), and seeking employment opportunities (

n = 51, 15.1%).

More than half of the participants met the currently recommended PA guidelines set by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDCs). Of the total 337 respondents, 213 (63.2%) indicated that they are active for at least 30 min on most days of the week, followed by 98 (29.1%) participants who responded that they exercise occasionally less than 30 min three days a week. The remainder responded that they do not participate in regular exercise. These responses were reinforced by their reported PA level in the TTM stages. In the TTM stage question, 206 (61.1%) participants responded that they engaged in regular PA within the past six months or for more than five months, followed by 28.5% (n = 96) participants who engaged in some PA, but not regularly.

3.2. Sample Trip Profile

Table 2 shows the trip-related characteristics of the participants’ most recent overnight stay at a hotel. The trip-related answers revealed that 238 (70.6%) participants were new customers, and 99 (29.4%) participants were repeat customers. For the total number of visits to a hotel, 31 (31.3%) indicated two times, and 31 (31.3%) said three times. The majority of the participants (

n = 122, 36.2%) reported staying at a hotel for two nights, followed by one night (

n = 94, 27.9%), and three nights (

n = 77, 22.8%). Half of the participants (

n = 171, 50.7%) reported that they made the primary decisions for the trip, 49 (14.5%) reported that the decisions were made by family members or relatives, 42 (12.5%) reported that the decisions were made by their partners, and 35 (10.4%) reported that the decisions were made jointly with significant others. Most of the visits (

n = 251, 74.5%) were for leisure purposes, 44 (13.1%) were for business purposes, and 42 (12.5%) were for both business and leisure purposes. Of the participants, 176 (52.2%) reported hearing about the hotel online, while 84 (24.9%) knew about the hotel already.

3.3. Analysis Procedure

For the analysis, thirty-six items—eight for grit, seven for hospitality attribute, seven for physical fitness attribute, four for enhanced hygiene standards attribute, four for visit intention, three for willingness to pay a premium, and three for eWOM factor—were computed through EFA in SPSS. Next, CFA was performed in Amos. Seven items were dropped to achieve the measurement model fit. Finally, twenty-nine items were included in the final hypotheses test.

3.4. Exploratory Factor Analysis

The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) was 0.88 with a significance level of p < 0.01. In the adequacy model, communalities were above 0.3. The seven-factor model explained 61% of the variance. The model had 6% of non-redundant residuals. All factor loadings in the pattern matrix generated by SPSS were above 0.5. Further, as evidence of discriminant validity, these factors did not show any cross-loadings. In the factor correlation matrix, none of the values were above 0.7.

3.5. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Eight items for grit, three for “hospital”ity services (HSs), five for physical fitness (PF), four for enhanced hygiene standards (EHSs), four for visit intention (VI), two for willingness to pay a premium (WPP), and three for eWOM were included in the CFA. The measurement model showed a good fit (

X2 = 753.01, d.f. = 381, normed

X2 = 1.98,

p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.05; IFI = 0.94; NFI = 0.88; CFI = 0.94; and TLI = 0.93). A summary of the descriptive analyses of the CFA is shown in

Table 3. Cronbach’s alpha showed a construct validity of above 0.7 and coefficients that ranged between 0.76 and 0.88 (

George & Mallery, 2019). The

t-statistics were significant (

p < 0.001). All of the variables were related significantly to their respective items (

H. C. Choi et al., 2020). Factor loadings, construct reliability, and average variance extracted (AVE) were checked to confirm the convergent validity (

Hair, 2009).

Table 3 shows the standardized factor loadings, in which all standardized loadings for latent constructs in CFA were high and significant in the range of 0.39 and 1.00. Most of the standardized loadings showed values above 0.8, while some of the loadings were above the recommended level of 0.6 (

Chin, 1998), indicating that both reliability and convergent validity criteria were met (

Anderson & Gerbing, 1988).

Table 3 also shows each of the items’ mean and standard deviation values. For grit, the items with the highest and lowest mean value were “I am a hard worker” (M = 4.08,

SD = 0.89) and “New ideas and projects sometimes distract me from previous ones” (M = 2.84,

SD = 1.05). For HS, items with the highest and lowest mean value were “hospitality certified healthcare staff” (M = 3.22,

SD = 1.19) and “smart-room technology” (M = 2.63,

SD = 1.13). For PF, items with the highest and lowest mean value were “sauna” (M = 2.37,

SD = 0.99) and “on-demand meditation programs” (M = 1.97,

SD = 1.05). For EHS, the items with the highest and lowest mean value were “mandatory face coverings” (M = 3.63,

SD = 1.24) and “touchless kiosks” (M = 3.25,

SD = 1.09).

For VI, the items with the highest and lowest mean value were “I would like to visit a hotel that provides health and WS” (M = 3.55, SD = 0.97) and “I will not stay at a hotel that does not provide health and WS” (M = 2.45, SD = 1.17). For WPP, items with the highest and lowest mean value were “I would be willing to pay more for health and WS in a hotel” (M = 2.66, SD = 1.18) and “I would like to pay a premium for health and WS in a hotel” (M = 2.34, SD = 1.17). For eWOM, items with the highest and lowest mean value were “I am willing to recommend a hotel that offers health and WS to someone who seeks my advice” (M = 3.91, SD = 0.94) and “I am willing to write reviews in social media if I am happy with health and WS” (M = 3.36, SD = 1.27).

The AVEs are shown in

Table 4. AVEs for all of the variables were above 0.5, which is more than the cutoff point (

Hair, 2009), except for the AVE for grit. Grit was measured with the short grit scale, a tested scale to measure grit score (

A. L. Duckworth & Quinn, 2009). Therefore, this study did not discard any of the eight items of the short scale to increase the AVE. In addition,

Fornell and Larcker (

1981) stated that AVE should be higher than 0.5, but the 0.4 value can still be acceptable if only composite/construct reliability (CR) is higher than 0.6. The CR value for grit was 0.86, so the construct’s convergent validity was assured. Moreover, the eight grit constructs’ discriminant validity was established, as the lowest AVE was higher than the highest square of the estimated correlation (

Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The square root of AVE for each factor was greater than the correlations among the variables.

3.6. Structural Equation Model

The SEM for the final model followed the stages of itemizing the variables, setting the relation among them, examining the model fit, making improvements and covariances among the factors if needed, and analyzing the path coefficients. The final model demonstrated a good fit (

X2 = 26.10 d.f. = 13, normed

X2 = 2.00,

p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.05; IFI = 0.98; NFI = 0.98; CFI = 0.98; and TLI = 0.96). The model fit is shown in

Table 5.

The hypothesized relations were measured based upon the t-value and p-value. Among the 16 relations tested, 14 were found to be related significantly and have positive effects at p < 0.05. All of the significant relations had a t-value of >1.96 or <−1.96. The PF (β = 0.25, t = 5.47, p < 0.05) and HS (β = 0.35, t = 5.82, p < 0.05) demonstrated a significant positive relation with grit, while EHS (β = 0.08, t = 1.29, p = 0.19) services were not related significantly relation to grit. The TTM shows a significant positive influence on grit (β = 0.14, t = 3.75, p < 0.05). In the final model, TTM was considered an exogenous variable that covaried with grit. The TTM variable was not affected systematically by changes in the other variables of the model, particularly by changes in the endogenous variables.

The customer engagement factors, i.e., WPP (β = 0.25,

t = 4.24,

p < 0.05), VI (β = 0.08,

t = 2.28,

p < 0.05), and eWOM (β = 0.21,

t = 2.95,

p < 0.05) had a significant positive relation with grit. HS showed a statistically significant positive relation with the WPP (β = 0.45,

t = 7.72,

p < 0.05), VI (β = 0.25,

t = 7.28,

p < 0.05), and eWOM (β = 0.30,

t = 4.25,

p < 0.05). EHS demonstrated a statistically significant positive relation with the WPP (β = 0.21,

t = 4.06,

p < 0.05), VI (β = 0.21,

t = 6.61,

p < 0.05), and eWOM (β = 0.25,

t = 3.91,

p < 0.05). PF had a statistically significant positive relation with the WPP (β = 0.32,

t = 4.29,

p < 0.05) and VI (β = 0.27,

t = 5.97,

p < 0.05), while PF was not related significantly with eWOM (β = 0.06,

t = 0.61,

p = 0.54). The

t-statistics, significance, and estimates of the final model are shown in

Table 6.

As noted above, the results suggested that while hypotheses H1, H2a, b, H3a, b, c, H4a, b, H5a, b, c, H6a, b, and cHH were supported, hypotheses H2c and H4c were not.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Today, staying at a hotel is more than just customers’ “traditional” escape from their daily living environment. Rather, they put more emphasis on the search for wellness and fulfillment, which has become a core value for today’s customers. As more and more consumers turn to venues that provide WSs to improve their health and well-being, this study identified grit as an important antecedent in selecting and using WSs during a hotel stay. The WS factor was categorized into three further components as follows: HS; PF, and EHS. Finally, this study identified the behavioral outcomes of customer engagement with the WSs.

The findings of this study indicate that grit has a significant positive effect on most WS factors and, in turn, influences key customer engagement outcomes, including WPP, eWOM, and VI. Among the WS, grit had the strongest effect on HS and PF, while it did not significantly affect EHS. Similarly, the WS factors differed in their contributions to customer engagement as follows: HS most strongly influenced WPP, EHS was most closely related to eWOM, and PF had a stronger relation with WPP and VI than with eWOM. Overall, these results suggest that grit plays a critical role in shaping customers’ engagement with wellness-oriented hospitality services, though certain services, such as EHS, may be less influenced by individual traits due to contextual factors like mandatory safety protocols. The following sections discuss these relationships in detail, examining how each WS factor interacts with customer engagement and the implications for hospitality management.

The study’s findings, as presented in

Table 6, indicate that grit significantly influences various WSs, with HS and PF notably impacted. This aligns with previous research suggesting that grit is positively associated with physical activity participation, as individuals with higher levels of grit are more likely to engage in and maintain physical activities (

Cosgrove et al., 2018;

Hein et al., 2019). Therefore, gritty customers tend to actively utilize HS and PF offerings during hotel stays, reflecting a consistent commitment to personal health and fitness. The significance of these findings implies that hotels emphasizing HS and PF can better engage customers with high levels of grit, increasing their willingness to pay a premium, revisit the hotel, and potentially share positive experiences through eWOM. This also suggests that incorporating robust health and fitness amenities is not merely a service enhancement but a strategic tool to attract goal-oriented, wellness-conscious clientele. Previous studies support this connection: participation in physical activity and wellness programs is often higher among individuals with traits like perseverance and self-discipline, which characterize gritty individuals (

Hein et al., 2019;

Kwon, 2021).

However, the lack of a significant relationship between grit and EHS was unexpected. This may be attributed to the nature of EHSs, which were primarily introduced as mandatory safety protocols during the COVID-19 pandemic. Since these services were compulsory, their adoption was less likely to be influenced by individual traits like grit, potentially explaining the absence of a significant correlation. Consequently, while EHS are essential for customer safety, they may not offer a competitive advantage in terms of customer engagement compared to other WSs.

Table 6 shows that HS had a significant positive relation with all of the customer engagement factors. This suggests that hotel customers value access to health-oriented services, which in turn increases their willingness to revisit, recommend, and invest in hotel experiences. For the hotel industry, this means that integrating HS into core operations can serve as a differentiator, positioning the property as a wellness destination rather than merely an accommodation provider.

Romero (

2017) found that behavior-specific antecedents motivate customers’ engagement behavior. The intention to use hospitality services contributed to the antecedents of customer engagement (

So et al., 2020). This explains the positive correlation between HS and customer engagement.

Table 6 also shows that EHS had a significant positive relation with all customer engagement factors, i.e., WPP, VI, and eWOM. Customers are willing to use services that enhance their motivation for self-protection. For hotels, this indicates that strong hygiene protocols, although initially introduced as compliance measures during the COVID-19 pandemic, have become an expected baseline for building trust. Executed effectively, EHS can not only safeguard guests but also improve brand image and encourage loyalty, particularly in the post-pandemic era where safety remains a top priority (

Tuzovic & Kabadayi, 2020). As a result, the hotels have an opportunity to enhance their brand value by earning customers’ trust.

As

Table 6 shows, PF had a significant positive relation with WPP and VI, though no significant relationship was found with eWOM. According to

Ferraresi (

2019), hotel customers are increasingly inclined to use physical fitness amenities during their stay when available. Physical fitness activities contribute directly to customers’ experiences and satisfaction (

Solas, 2023), which in turn heightens their willingness to revisit and to pay a premium for hotels that support their health-oriented lifestyle. For the hotel industry, this means that investing in high-quality fitness centers, yoga studios, or personalized training programs can be a strong driver of repeat visitation and revenue growth, particularly among health-conscious and gritty customers who persistently pursue long-term wellness goals (

Solas, 2023).

The absence of a significant relationship between PF and eWOM may stem from the way customers use these services. Many guests who benefit from hotel fitness facilities may not feel compelled to post online reviews, preferring instead to quietly incorporate fitness into their routines. In addition, survey participants with strong intentions to use PF amenities may not be active on social media. Thus, while PFs clearly boost satisfaction and loyalty, they may not automatically generate digital word of mouth. Hotels may need to proactively encourage online sharing, through incentives, digital campaigns, or community-building activities, to translate positive PF experiences into eWOM (

Mathews et al., 2022). Moreover, the insignificant relation could have been attributable to the way that the eWOM items (i.e., “I am willing to write reviews on social media if I am happy with health and wellness services”) were worded (

Elson, 2016).

As

Table 6 shows, grit had a significant positive relation with all customer engagement factors, namely WPP, VI, and eWOM. Perseverance (i.e., grit) has also been shown to correlate positively with satisfaction (

Kim et al., 2019), suggesting that gritty customers derive greater fulfillment from wellness-oriented services and are therefore more inclined to revisit and recommend hotels that support their long-term health goals. For the hotel industry, this implies that targeting gritty consumers, such as business travelers, athletes, or wellness-focused tourists, by offering tailored wellness programs can lead to stronger loyalty, premium pricing opportunities, and organic advocacy.

These findings also substantiate the conceptual transformation of hospitality into ‘Hospital’ity.’ The significant role of HS in driving customer engagement demonstrates that hotels are increasingly adopting attributes traditionally associated with healthcare environments, such as air quality, therapeutic comfort, and wellness-focused amenities. This integration reflects a shift from hospitality as a domain of leisure and accommodation toward “Hospital’ity,” where health, safety, and well-being are central to the guest experience. Prior research has similarly shown that innovation and co-creation in hospitality positively influence guest satisfaction and revisit intention (

Sharma & Bhat, 2022), reinforcing the industry’s move toward wellness-centered value propositions. The technological dimensions in HS further reinforce the transformation of hospitality into “Hospital’ity,” as innovations such as smart-room systems, touchless kiosks, patient health-tracking, and entertainment tablet not only enhance perceptions of safety and wellness but also strengthen customer engagement (

Sharma & Bhat, 2022).

In addition, the significant correlation between grit and TTM stages of change indicates that individuals with higher grit levels are more likely to sustain progress toward wellness behaviors (

Marentes Castillo et al., 2022). This finding aligns with

Reed et al. (

2013), who observed grit’s role in maintaining behavior change. From a managerial perspective, this means that hotels can design tiered or progressive wellness offerings, such as long-term fitness memberships, multi-day wellness retreats, or loyalty programs centered on wellness milestones, that align with gritty customers’ persistence and commitment (

Z. Liu, 2024). By doing so, hotels can transform wellness services from one-time amenities into integral components of customers’ ongoing wellness journeys.

4.1. Theoretical Implications

This study made an important contribution to TTM theory by creating a TTM–grit–WS–customer engagement model and conceptualizing, evaluating, and examining grit’s effect on WSs and behavioral outcomes. After reviewing a significant amount of the grit and wellness literature, this research is among the first few studies that investigated the role that grit plays in WS and customer engagement. The findings enrich grit research by enhancing the short grit scale’s item reliability. Further, the study developed and examined some important and future wellness service items, such as the EHS, which have not been identified in previous studies and can fill the gaps in the limited number of wellness instruments available.

The study also provides information on how customers become engaged with WSs. Gritty customers are willing to pay more for WSs and engage in WOM activity. As using WSs may be more expensive than regular hotel amenities, this study highlights the importance of expanding the scope of WSs based upon the interest of customers who want to use WSs even at a premium rate. This study’s results highlight the significance of customer behavioral outcomes, such as visit intention with respect to grit and WSs.

4.2. Practical Implications

The findings of this study provide important insights for the hospitality industry, particularly into ways to integrate WSs to improve service quality and customer engagement. By applying these insights, hospitality providers can design and implement both new and existing WSs more effectively to meet the needs of customers, particularly those with high levels of grit. Understanding grit’s role in fitness activities allows businesses to promote wellness services more explicitly and engage customers in a more meaningful way. This engagement can reduce advertising costs while it increases customer satisfaction, as satisfied customers are more likely to revisit and recommend the hotel to others, thereby creating a positive business cycle. Further, the study revealed that gritty customers place greater importance on physical fitness and hospitality attributes, which makes them more likely to engage in wellness activities. Identifying and understanding these customers’ needs can make retention easier, as it is more cost-effective to nurture existing loyal customers than to attract new ones.

The study also highlights that grit has a significant effect on behaviors such as visit intention, willingness to pay a premium, and eWOM. As customers turn increasingly to online platforms to share experiences, hospitality providers must recognize the value of eWOM and the potential of gritty customers who are willing to pay more for exclusive wellness amenities. This recognition can help businesses attract and retain customers to ensure their competitiveness and long-term success. Finally, the research related grit to the TTM in the hospitality context by showing that gritty customers demonstrate persistence in maintaining wellness behaviors, even outside their usual routines. This insight expands the application of TTM in wellness studies and provides actionable strategies to design wellness experiences that cater to guests at different stages of behavioral readiness, support their wellness journeys, and enhance their satisfaction overall.

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

Although WSs are attracting a great deal of attention worldwide, the results of this study may reflect the WSs only in U.S. hotels. In future studies, wellness hospitality research should be conducted in the context of other countries. Further, the study was conducted while the COVID-19 restrictions still prevailed, and such restrictions may have affected the results. It is also possible that newer and innovative WSs have been developed, which this study might have failed to identify. This study adopted several existing studies, and future studies can develop new scale items to measure customer behavioral intentions. Further, the time lag between the actual hotel stay and taking the survey may have affected the accuracy of the participants’ responses. Future studies could conduct surveys on-site to avoid the time lag between the hotel stay and survey participation. Not including niche demographics in this study might also have limited its scope to the different market segments. Moreover, there is a possibility that some participants might have predicted that they would fulfill their behavioral intentions but failed to engage in those behaviors. Thus, it would be worthwhile to survey customers who truly used WSs in hotels. Conducting a qualitative study of wellness hotel services could provide a new area of exploratory research in the hospitality industry.