1. Introduction

Customer satisfaction (CS) is a strategic axis of competitiveness in services, as it is closely associated with loyalty, positive word-of-mouth, and sustained profitability (

Mittal et al., 2023). In the restaurant sector—where staff–customer interactions are intensive and consumption is highly sensory—CS functions both as a signal of perceived quality and as an indicator of the alignment between customer expectations and service performance (

Bonfanti et al., 2023;

Hassan et al., 2024). In contexts of volatile demand, monitoring CS enables firms to redesign processes and prioritize investments (

Agag et al., 2023).

Traditionally, CS measurement has relied on standardized scales. SERVQUAL (

Parasuraman et al., 1988;

Abdullah et al., 2022) assesses the gap between expectations and perceptions across five dimensions (tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy), offering strong diagnostic power for managerial action. SERVPERF (

Cronin & Taylor, 1992;

Praditbatuga et al., 2022) eliminates the expectation of focusing solely on performance, instead privileging parsimony and psychometric consistency. The American Customer Satisfaction Index (

Fornell et al., 1996,

2016;

Anderson et al., 2004) extended these frameworks by linking CS to profitability, productivity, and shareholder value. Together, these instruments have facilitated continuous improvement in restaurants by identifying areas for improvement, such as waiting times, order accuracy, and staff friendliness. However, their reliance on recall surveys introduces social desirability bias and delayed feedback, limiting their utility in fast-paced service environments.

Over the past five years, the explosion of customer-generated data—reviews, in-store images and videos, kiosk interactions, mobile apps—combined with advances in deep learning has expanded the methodological toolkit for CS research (

Yang et al., 2024;

Wen et al., 2023). In the hospitality and tourism industries, neural networks have been applied to sentiment analysis, demand forecasting, recommendation systems, and emotion recognition. Review mining has documented shifts in the volume and tone of online reviews during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, with hygiene, waiting times, and capacity restrictions emerging as critical factors affecting satisfaction and return intentions (

Pleerux & Nardkulpat, 2023). Computer vision and multimodal analysis (image + text) have enabled automatic detection of smiles, gestures, queues, and compliance with standards, providing real-time indicators that complement surveys and the Net Promoter Score (

Yildirim et al., 2023;

Pereira et al., 2024).

Neural methods, however, are heterogeneous. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) excel in image-related tasks such as facial expression and posture recognition, achieving robustness under variable lighting and angles (

LeCun et al., 2015). Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and long short-term memory networks (LSTMs) effectively capture sequential dependencies in text, but often underperform in comparison to transformers when handling domain-specific jargon or long-range semantic ambiguity (

Schmidhuber, 2015;

Yang et al., 2024). Transformers, such as BERT and ERNIE, leverage self-attention to model global dependencies, showing superior performance in sentiment classification and aspect extraction from reviews (

Wen et al., 2023;

Zhang et al., 2022). Recent reviews confirm that transformers outperform CNNs and LSTMs in terms of F1-score and robustness with large, heterogeneous datasets, although concerns remain regarding interpretability and computational demands (

Chutia et al., 2024;

Vargas-Calderón et al., 2021).

Beyond performance, the adoption of AI in the hospitality industry raises significant ethical and social challenges. A scoping review highlights risks such as opacity, algorithmic bias, privacy concerns, and unregulated biometric surveillance, underscoring the sector’s lag in establishing governance frameworks compared with other industries (

Zhang et al., 2022). Complementary evidence shows that while AI assistants, predictive analytics, and personalization tools can enhance service quality and efficiency, risks include job displacement, customer mistrust, and data misuse (

Limna, 2023;

Zafar & Zafar, 2025). Given that hospitality is fundamentally anchored in human interaction and trust, responsible adoption requires transparency, fairness, accountability, and clear consent protocols (

Morosan, 2022).

In summary, the current literature converges on three implications for CS research in gastronomy and hospitality. First, combining classical scales (e.g., SERVQUAL, SERVPERF, ACSI) with digital signals (such as reviews, behavioral data, and images) enhances sensitivity to micro-level changes in customer experience (

Fornell et al., 2016;

Vargas-Calderón et al., 2021). Second, neural analytics—particularly transformers for text and CNNs for images—improve the detection of satisfaction and dissatisfaction, supporting more responsive service management (

Yildirim et al., 2023). Third, explainability, ethical safeguards, and model governance are essential to ensure trust and responsible adoption (

Zafar & Zafar, 2025). Guided by this framework, the present study develops and evaluates a CNN-based model for automatically classifying satisfied and dissatisfied restaurant customers from images. It benchmarks the model’s performance against alternative methods and incorporates textual review evidence to provide a multimodal perspective on customer satisfaction.

Beyond this empirical aim, the study addresses a specific research gap identified in the literature: while artificial intelligence has been widely applied to analyze online reviews, sentiments, and recommendations, few studies have validated deep learning models under real-world restaurant conditions. Prior research has largely remained confined to laboratory experiments or digital datasets, overlooking the spontaneous and non-verbal expressions that emerge in live service encounters. The present research, therefore, contributes by operationalizing classical satisfaction frameworks through an innovative methodological approach—integrating convolutional neural networks (CNNs) into actual restaurant environments to measure satisfaction non-intrusively and in real time. By embedding deep learning within live operations, the study extends classical models such as SERVQUAL, SERVPERF, and ACSI, demonstrating how implicit visual signals can complement traditional survey-based measures. This methodological convergence between established service quality theories and modern neural architectures represents a step forward in bridging human-centered hospitality research with the emerging field of responsible artificial intelligence applications in service management.

Accordingly, this study aims to evaluate the feasibility of using convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to automatically classify restaurant customers’ satisfaction from facial expressions captured in real service settings. Guided by this objective, the research addresses three key questions: (1) Can CNNs accurately classify satisfaction based on facial cues in real-world conditions? (2) How does their performance compare with traditional machine learning models such as Support Vector Machines and Random Forest? and (3) to what extent do CNN-based classifications correspond to theoretical constructs of service quality described in classical frameworks such as SERVQUAL and the Expectation–Disconfirmation Theory? These questions form the basis for three testable hypotheses that structure the empirical analysis and discussion presented in the following sections.

2. Theoretical Framework

Research on customer satisfaction (CS) in hospitality has evolved along two complementary trajectories. The first focuses on traditional models and survey-based instruments, such as the Expectation–Disconfirmation Theory, SERVQUAL, SERVPERF, the Kano model, and the American Customer Satisfaction Index. These frameworks established the conceptual and methodological foundations of CS assessment, linking perceptions of service quality to behavioral outcomes such as loyalty and profitability. The second trajectory reflects the advent of artificial intelligence (AI) and neural methods, which enable the analysis of unstructured, multimodal, and real-time data (such as reviews, images, and sensor records) through architectures like convolutional neural networks (CNNs), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), and transformers. This dual perspective highlights that while traditional approaches remain indispensable for capturing declared perceptions, AI-based models expand analytical capacity by incorporating implicit signals and reducing bias. The present study is situated at this intersection, building on both traditions to develop a CNN-based approach for the automated measurement of satisfaction in restaurants.

2.1. Traditional Methods

This group includes a wide variety of methods, some of which are discussed below:

The Expectation–Disconfirmation Theory (ECT), formulated by

Oliver (

1980), posits that satisfaction arises from the comparison between perceived performance and prior expectations. According to ECT, positive disconfirmation generates satisfaction, while negative disconfirmation results in dissatisfaction.

The Kano Model, developed by Noriaki Kano in 1984, emerged as a conceptual tool for classifying product or service attributes based on their impact on customer satisfaction. The central premise is that not all attributes have the same effect: some are basic and expected, others increase satisfaction linearly, and others delight customers by exceeding expectations.

The model distinguishes five categories:

Must-be attributes: basic features whose absence generates strong dissatisfaction, but whose presence is hardly perceived as satisfying (e.g., hygiene in a restaurant).

One-dimensional attributes: features whose improvement directly translates into increased satisfaction, while their deficiency generates dissatisfaction (e.g., speed of service).

Attractive attributes: unexpected elements that delight customers and produce high levels of satisfaction, although their absence does not generate dissatisfaction (e.g., a complimentary item on the table).

Indifferent attributes: characteristics that do not significantly influence satisfaction or dissatisfaction.

Reverse attributes: features whose presence may displease specific customers, while their absence may actually be preferred.

Parasuraman et al. (

1988) proposed SERVQUAL (Service Quality), a 22-item scale designed to evaluate the gap between expectations and perceptions across five dimensions: tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy. Years later,

Cronin and Taylor (

1992) developed a simplified version, SERVPERF (Service Performance), which measures only perceptions, eliminating expectations. This alternative provides greater parsimony and psychometric stability (

Cronin & Taylor, 1992). The approach is based on the idea that administering two surveys (expectations and perceptions) is more complex than administering only one, and that perceptions are, to some extent, already mediated by initial expectations—that is, our evaluation of what is observed is conditioned by what we expected beforehand.

The American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI) was established in 1994 by Claes Fornell and colleagues as a national measure of consumer satisfaction in the United States. Grounded in expectation–disconfirmation theory, the model integrates three determinants of satisfaction: customer expectations, perceived quality, and perceived value. Based on these determinants, it predicts outcomes such as overall satisfaction, loyalty, and complaints (

Fornell et al., 1996).

Its importance lies in establishing an empirical connection between customer satisfaction levels and the financial performance of organizations, showing that satisfaction is a predictor of profitability, productivity, and customer loyalty (

Fornell et al., 2016;

Anderson et al., 2004). Moreover, the index has served as an international benchmark, giving rise to analogous models in Europe, Asia, and Latin America.

2.2. Modern Methods

Modern approaches to CS analysis are grounded in artificial neural networks (ANNs), which have demonstrated the ability to capture nonlinear, high-dimensional patterns that traditional statistical models often overlook (

LeCun et al., 2015;

Schmidhuber, 2015). Their adoption in hospitality research reflects the growing availability of big data and the need for real-time, non-intrusive measurement of customer experiences (

Mariani et al., 2023).

Among ANN architectures, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) stand out for image-based analysis. Initially developed for computer vision, CNNs are particularly effective at detecting facial expressions, gestures, and environmental cues in dynamic contexts such as restaurants. Studies confirm their robustness under variable angles, lighting conditions, and crowd density, enabling near real-time classification of satisfaction and dissatisfaction (

Yildirim et al., 2023;

Pereira et al., 2024). Their main limitations lie in the need for large, labeled datasets and in addressing privacy concerns and obtaining informed consent when applied to customer monitoring (

Shafie et al., 2024).

Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and their variants, such as long short-term memory networks (LSTMs) and gated recurrent units (GRUs), were designed to process sequential information, making them suitable for text-based data such as reviews. They capture temporal dependencies in sequences but are less effective with long texts or domain-specific jargon, where performance tends to degrade (

Schmidhuber, 2015;

Yang et al., 2024). In gastronomy, their contribution has been primarily exploratory, and more powerful architectures are increasingly replacing them.

Transformers have redefined the field of natural language processing. By leveraging self-attention mechanisms, models such as BERT and ERNIE achieve superior results in sentiment classification, aspect-based analysis, and recommendation systems (

Wen et al., 2023;

Zhang et al., 2022). In hospitality, transformers excel in extracting fine-grained insights from reviews, identifying both explicit satisfaction drivers (e.g., food quality, staff friendliness) and implicit concerns (e.g., noise, hygiene). However, their high computational cost and limited interpretability pose barriers to practical adoption in small service firms.

Finally, multimodal approaches integrate signals from different sources—text, images, and behavioral data—to provide a holistic assessment of CS. Recent studies demonstrate that combining review analysis with facial recognition or transactional data enhances predictive accuracy and managerial relevance (

Vargas-Calderón et al., 2021;

Kim et al., 2024). Nevertheless, these models are complex to implement, require cross-disciplinary expertise, and amplify concerns regarding bias, explainability, and ethical safeguards (

Morosan, 2022;

Kim et al., 2024).

Together, these modern methods position AI as a powerful complement to traditional survey-based instruments. By capturing both explicit perceptions and implicit signals, they allow for more comprehensive, dynamic, and context-sensitive evaluations of customer satisfaction in hospitality and gastronomy.

As summarized in

Table 1, approaches to measuring customer satisfaction in hospitality have evolved from theory-driven, survey-based instruments (ECT, SERVQUAL, SERVPERF, Kano, ACSI) to data-driven, AI-enabled models (CNNs, RNNs, transformers, multimodal systems).

Traditional frameworks remain valuable for diagnosing service attributes and benchmarking performance, but their reliance on declarative responses and delayed feedback limits their responsiveness in dynamic service settings (

Parasuraman et al., 1988;

Fornell et al., 1996;

Praditbatuga et al., 2022). In contrast, modern neural methods enable the analysis of large-scale, unstructured, and real-time signals—such as facial expressions, review texts, and multimodal interactions—delivering higher accuracy and sensitivity to micro-level changes in customer experience (

Yildirim et al., 2023;

Wen et al., 2023;

Zhang et al., 2022). However, these architectures also raise challenges related to explainability, bias, and ethical safeguards, which are particularly salient in hospitality contexts where trust and personalization are central to service quality (

Morosan, 2022). This comparative overview underscores the rationale for the present study: to test the applicability of a convolutional neural network for classifying customer satisfaction in restaurants. It benchmarks this performance against alternative approaches while acknowledging the importance of integrating ethical considerations into AI-driven service systems.

In conclusion, the literature highlights that both traditional and modern approaches contribute to a comprehensive understanding of customer satisfaction in the hospitality industry. Classical models such as SERVQUAL, SERVPERF, and ACSI remain indispensable for diagnosing service attributes and linking satisfaction to organizational outcomes. At the same time, neural methods expand analytical capacity by capturing implicit, real-time signals from images and texts. Within these, CNNs have demonstrated particular effectiveness in detecting facial expressions and non-verbal cues under real-world restaurant conditions, making them especially suited for non-intrusive and dynamic measurement of satisfaction (

Yildirim et al., 2023;

Pereira et al., 2024). At the same time, challenges regarding data requirements, model interpretability, and ethical safeguards remain central concerns (

Morosan, 2022). Guided by this theoretical framework, the present study develops and evaluates a CNN-based model for classifying satisfied and dissatisfied restaurant customers from facial images. It benchmarks the model’s performance against alternative methods and illustrates how AI can complement rather than replace traditional instruments of customer satisfaction research.

2.3. Research Questions and Hypotheses

RQ1: Can convolutional neural networks (CNNs) accurately classify restaurant customers’ satisfaction based on facial expressions captured in real service environments?

RQ2: How does the performance of CNN-based classification compare with traditional machine learning models such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Random Forest (RF)?

RQ3: To what extent do CNN-based satisfaction classifications correspond to theoretical constructs of service quality (e.g., empathy, responsiveness) described in SERVQUAL and related models?

Based on these questions, the study tests the following hypotheses:

H1: CNNs achieve significantly higher predictive accuracy than traditional machine learning models (SVM, RF) in classifying customer satisfaction from facial images.

H2: CNN-based classifications of satisfaction are consistent with the theoretical dimensions of service quality and the expectation–disconfirmation framework.

H3: CNN-based methods represent a valid and non-intrusive complement to classical survey-based satisfaction measurement instruments in restaurant settings.

These research questions and hypotheses establish the logical foundation of the empirical design and articulate the study’s dual contribution. On one hand, they enable a systematic comparison between deep and traditional machine learning models in recognizing satisfaction through visual cues. On the other hand, they operationalize core constructs of service quality theory—such as empathy, responsiveness, and reliability—within an AI-based measurement framework. By empirically testing how convolutional neural networks capture customers’ affective responses under authentic service conditions, the study connects technological performance with the psychological mechanisms underlying satisfaction formation. This theoretical–methodological alignment provides the basis for the experimental procedures detailed in

Section 3.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

This study employed a quantitative and experimental design aimed at evaluating the feasibility of automatically classifying restaurant customers’ satisfaction based on facial images. The methodological strategy integrated direct in situ data collection at the service point with the application of deep learning techniques implemented in the R programming language. The choice of a convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture is informed by its suitability for image recognition tasks, and by recent evidence showing the effectiveness of deep learning models for satisfaction prediction tasks (

Le et al., 2024), particularly facial emotion classification in dynamic service environments (

LeCun et al., 2015;

Yildirim et al., 2023). In addition, two baseline models, Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Random Forest (RF), were trained using the same preprocessed dataset, enabling comparative benchmarking of CNN performance against traditional machine learning approaches.

The experimental design was structured to test the proposed hypotheses (H1–H3), evaluating the comparative performance of CNNs versus traditional models (H1), their consistency with established service quality and satisfaction theories (H2), and their feasibility as a non-intrusive complement to classical survey-based instruments (H3). These hypotheses guided the data collection, model training, and analytical procedures detailed in the following subsections.

3.2. Data Collection

The empirical study was conducted at Irati Restaurant, located in the north-central area of Quito, Ecuador. The establishment has been operating for three years. It offers a wide gastronomic selection of over 50 dishes and more than 150 wine labels, creating an environment suitable for capturing diverse customer experiences.

Data collection took place at the payment point, where cameras were discreetly installed to capture customers’ facial images at the moment of service closure. Each customer was invited to voluntarily register their satisfaction level by pressing one of two buttons—“satisfied” or “not satisfied”. This binary self-report was then used as the ground truth label for subsequent supervised training.

From an initial dataset of approximately 5000 images, a total of 2969 valid images were obtained after applying quality control filters. The final dataset comprised 1059 satisfied and 1910 dissatisfied customers. Excluded cases corresponded to (i) missing button selection, and (ii) insufficient visual quality (lighting issues, occlusions, camera angle, or resolution problems).

All participants were informed that their data would be used exclusively for academic research purposes. Informed consent was obtained, and data handling complied with ethical standards for service research, including privacy protection and anonymity. Immediately after collection, each facial image was anonymized by removing any metadata and replacing identifiable visual features with encoded numerical representations (pixel matrices) used solely for training and validation. No raw or personal data were stored, shared, or transferred outside the research environment. All files were stored on an encrypted local server with restricted access, and the dataset was permanently deleted upon completion of the analysis. The study fully adhered to Ecuadorian regulations for minimal-risk, non-interventional research and to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 revision), ensuring informed consent, voluntary participation, and respect for data privacy and integrity. In compliance with Ecuadorian ethical regulations, the study qualified as minimal-risk and non-interventional, thus exempt from formal CEISH approval.

3.3. Data Preprocessing

The dataset underwent a multi-stage preprocessing pipeline to ensure image quality and dataset homogeneity prior to model training.

Initial Cleaning. Images with low capture quality (e.g., excessive blurring, poor lighting, occlusions) or without the corresponding satisfaction label were excluded. This process ensured that only valid observations remained for supervised learning.

Normalization. All images were resized to a standard resolution of 224 × 224 pixels, which is consistent with the resolution used in CNN architectures. Pixel intensity values were rescaled to the [0, 1] range to facilitate network convergence. Data augmentation techniques—such as random rotations, horizontal flips, and shifts—were applied to enhance robustness against variability in facial poses and environmental conditions.

Labeling. Images were automatically assigned to one of two categories (satisfied or not satisfied) based on the button the customer pressed during the data collection process. This supervised labeling process allowed for consistent integration with the training and validation data generators in R.

This preprocessing strategy guaranteed a clean and balanced dataset, improved the generalization capacity of the CNN, and minimized the risk of overfitting during training.

3.4. Model Training

For the main experiment, a convolutional neural network (CNN) was implemented using a MobileNetV2 architecture with transfer learning. Pretrained weights from the ImageNet dataset were employed to accelerate convergence and reduce the need for extensive local data. The model was developed in R (version 4.2.3), using the Keras (version 2.11) and TensorFlow (version 2.12) libraries, and executed on a workstation equipped with an Intel Core i7 processor, 32 GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX 3060 GPU (12 GB).

The training pipeline included the following specifications:

Batch size: 32 images per iteration.

Number of epochs: up to 100, with early stopping applied.

Optimizer: Adam algorithm, with an initial learning rate of 0.001.

Loss function: binary cross-entropy.

Regularization: Dropout layers were applied to mitigate overfitting.

Callbacks: callback_model_checkpoint() (to save the best-performing model), callback_reduce_lr_on_plateau() (to dynamically adjust the learning rate), and callback_early_stopping() (to terminate training when validation loss ceases to improve).

To address class imbalance (1059 satisfied vs. 1910 dissatisfied), class weights were introduced to ensure the model did not become biased toward the majority class. Cross-validation was used to validate robustness and reduce the risk of overfitting to a specific subset of the dataset.

3.5. Baseline Models

To provide a comparative benchmark for the CNN, two widely used machine learning classifiers were trained on the same preprocessed dataset:

Support Vector Machine (SVM): Implemented with a radial basis function (RBF) kernel, optimized using grid search for hyperparameters (C and gamma).

Random Forest (RF): Configured with 500 decision trees, using the Gini index for node splitting and bootstrap sampling.

Both models were trained in R using the e1071 and randomForest packages, respectively, following standard practices in applied ML research (

Machado et al., 2025). Preprocessed images were vectorized prior to training, ensuring consistency across methods. The same training/validation splits used in the CNN experiment were applied to the baseline models, allowing for a direct comparison of performance across accuracy, recall, specificity, F1-score, and AUC metrics.

These baselines represent conventional approaches commonly applied in classification tasks within hospitality and service research (e.g.,

Sun & Sun, 2021), thereby enabling a robust evaluation of whether deep learning architectures offer significant advantages over traditional machine learning methods.

To summarize, the methodological design integrated both deep learning (CNN) and traditional machine learning approaches (SVM and Random Forest) to ensure a robust comparative evaluation.

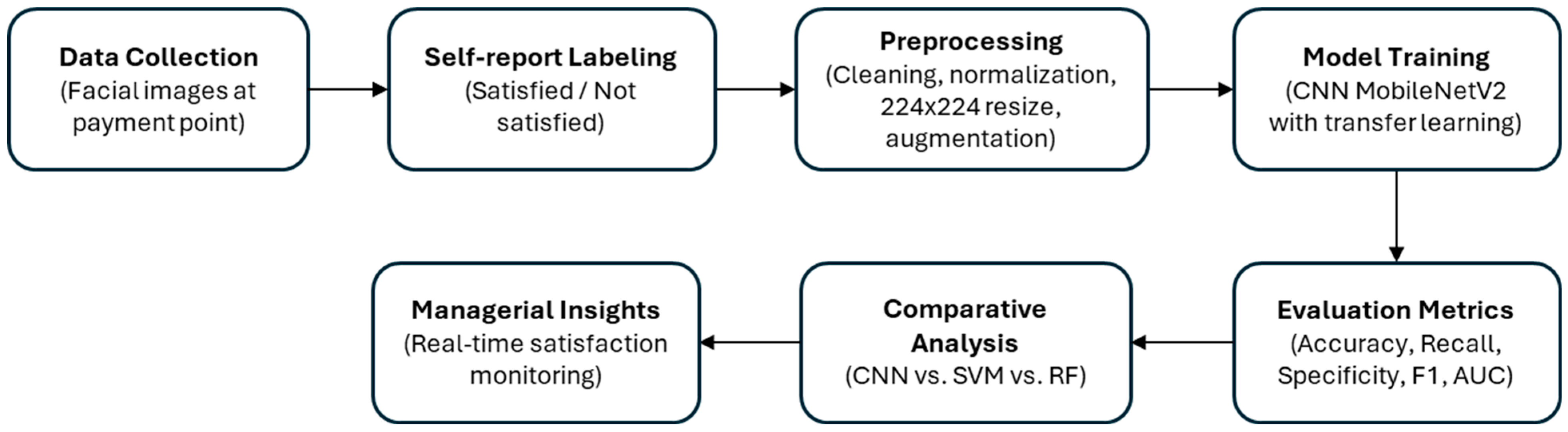

Figure 1 provides a visual overview of the complete research workflow, from data collection and preprocessing to model training, evaluation, and managerial interpretation.

This diagram (

Figure 1) facilitates understanding of the experimental sequence and highlights how each stage contributes to the overall objective of assessing customer satisfaction through automated image analysis.

4. Results

Building on the methodological framework summarized in

Figure 1, this section presents the empirical findings derived from the CNN experiment and its comparison with baseline models. The results are presented in the following structure: first, a description of the performance metrics of the proposed CNN is provided, followed by an analysis of classification errors using the confusion matrix, an evaluation of discriminative power via the ROC curve, and finally, a comparative assessment against Support Vector Machine and Random Forest classifiers.

The empirical experiment was conducted at Irati Restaurant, located in the north-central area of Quito, Ecuador. The establishment, with three years of operation and a diverse gastronomic offer of more than 50 dishes and 150 wine labels, provided an appropriate environment for testing the feasibility of automated customer satisfaction measurement. Data collection followed the protocol described in

Section 3, where facial images were captured at the payment point and labeled through the binary self-report mechanism (satisfied vs. not satisfied). After the preprocessing stage (cleaning, normalization, augmentation, and labeling), the validated dataset comprised 2969 images, distributed across 1059 satisfied and 1910 dissatisfied customers. This class imbalance was explicitly addressed through weighting during model training (see

Section 3.4).

4.1. CNN Performance

Table 2 summarizes the performance metrics obtained by the convolutional neural network (CNN) implemented with transfer learning (MobileNetV2 pretrained on ImageNet). The model achieved an overall accuracy of 91.2%, exceeding the 90% threshold considered robust for supervised classification tasks in image recognition domains. Sensitivity (recall) reached 92.8%, demonstrating the model’s ability to correctly identify satisfied customers, while specificity was 89.6%, reflecting adequate capacity to reduce false positives in the dissatisfied class. The F1-score (91.0%) confirmed a balanced trade-off between precision and recall.

These results directly reflect the preprocessing strategies applied: image normalization and augmentation improved generalization, while the use of class weights mitigated bias caused by the higher number of dissatisfied customers. Thus, the methodological decisions outlined in

Section 3.3 and

Section 3.4 made a decisive contribution to achieving balanced performance.

4.2. Confusion Matrix and Error Analysis

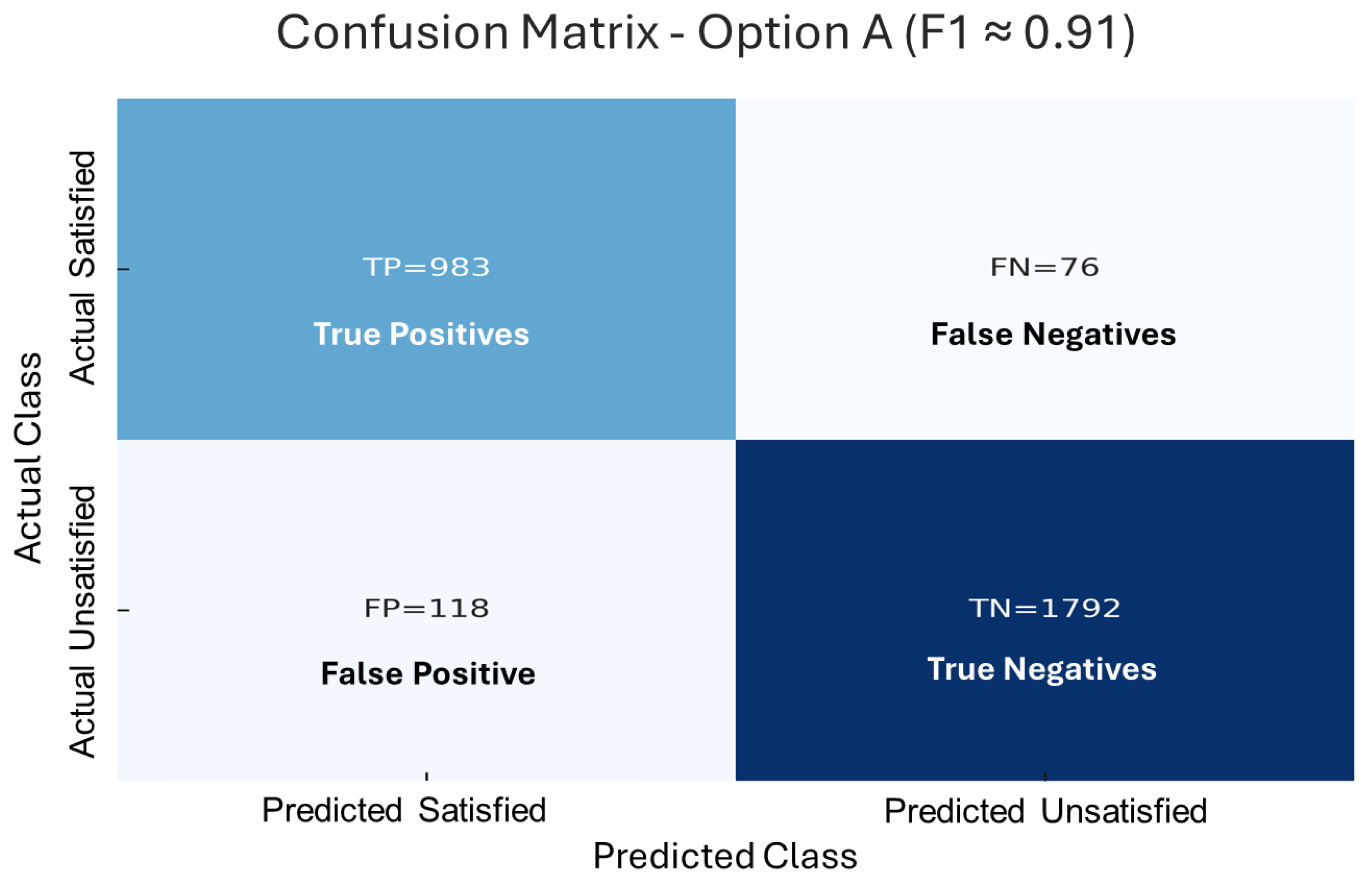

The confusion matrix (

Figure 2) provides further insight into classification errors. Correct classifications dominated both classes, but misclassifications were concentrated in borderline cases where customers displayed ambiguous expressions—slight smiles, neutral or mixed-affect faces. These errors illustrate the challenge of operationalizing “satisfaction” through static facial features alone, as certain expressions do not map unambiguously to binary categories. This finding underscores the importance of multimodal approaches (e.g., combining facial images with textual reviews), as suggested in

Section 3.5.

From a managerial perspective, these errors suggest that automated systems may slightly underestimate dissatisfaction in cases where neutral expressions mask discontent, or overestimate satisfaction when subtle expressions resemble smiles. Therefore, although the CNN provides a powerful diagnostic tool, its outputs should be interpreted as indicators rather than absolute measures.

4.3. ROC Curve Analysis

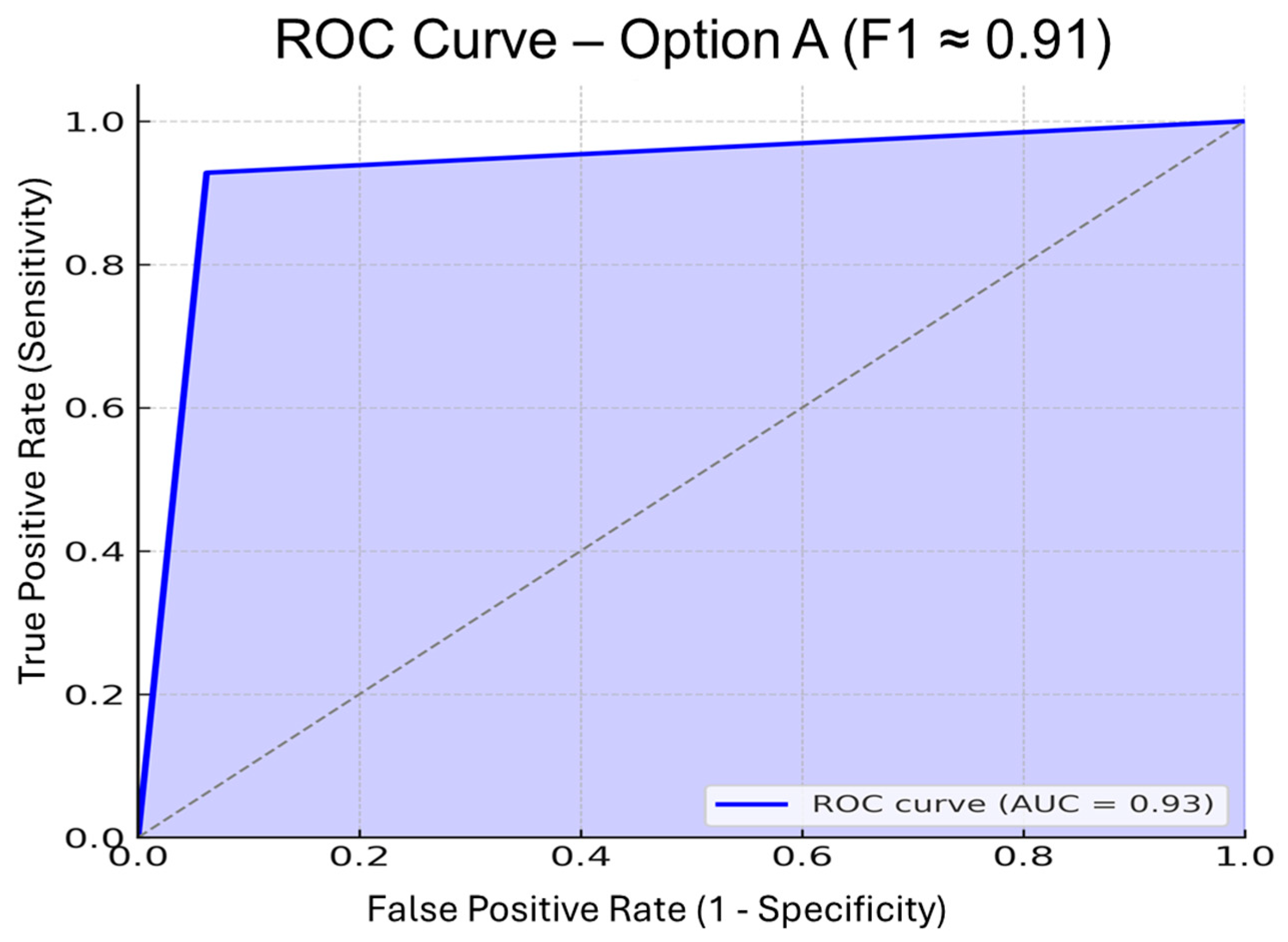

The ROC curve yielded an area under the curve (AUC) of approximately 0.93 (see

Figure 3).

This value indicates excellent discriminative capacity, comparable to benchmark levels reported in hospitality studies applying emotion recognition with CNNs. High AUC scores are particularly relevant in practice, as they imply that the model can maintain robust performance even when decision thresholds are adjusted (e.g., setting stricter cut-offs to minimize false positives among dissatisfied customers). This result validates the use of transfer learning with the MobileNetV2 architecture. It confirms that the model sustains strong predictive power across different threshold settings, making it suitable for real-time restaurant applications.

This result confirms the advantage of transfer learning with pretrained weights. By leveraging prior feature extraction from large-scale datasets, the CNN achieved strong predictive power despite the modest size of the local dataset (2969 images). The methodological choice of employing MobileNetV2 with transfer learning was therefore validated.

4.4. Comparison with Baseline Models

Table 3 compares the performance of CNN with two conventional machine learning approaches—Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Random Forest (RF)—both trained on the same preprocessed dataset. The CNN outperformed both alternatives across all metrics, with an accuracy advantage of 8.8 percentage points over RF and 14.8 points over SVM. Sensitivity and specificity exhibited similar trends, with the CNN maintaining superior balance.

The superiority of the CNN validates the methodological rationale presented in

Section 2.1: deep architectures are better suited for extracting nonlinear, high-dimensional features from facial images than vectorized approaches underlying SVM and RF. These findings also align with the literature (

Sun & Sun, 2021;

Khedr & Rani, 2024), which reports similar performance gaps between deep learning and classical models in service and operational contexts.

4.5. Synthesis of Findings

In summary, the empirical evidence reveals several key findings.

Robust classification performance of the CNN: The convolutional neural network, trained with transfer learning (MobileNetV2), achieved balanced and reliable results across all evaluation metrics, with overall accuracy above 91%, sensitivity above 92%, and specificity close to 90%. These results are directly linked to the preprocessing pipeline—image cleaning, normalization, and augmentation—that enhanced generalization capacity, as well as to the decision to mitigate class imbalance through weighted training.

Error patterns and the role of multimodality: Misclassifications were primarily concentrated in ambiguous expressions, such as neutral faces or subtle smiles, which complicate binary categorization. This highlights an intrinsic limitation of single-modality approaches and supports the potential integration of multimodal methods (e.g., combining facial expressions with textual reviews or transactional data) to capture more nuanced dimensions of satisfaction.

High discriminative power of the CNN: The ROC analysis (AUC = 0.93) confirmed that the model maintained strong predictive performance even under varying thresholds, validating its suitability for real-time applications in dynamic service environments. This finding supports the methodological choice of leveraging pretrained weights from large datasets, which allowed robust outcomes despite the moderate size of the local dataset (2969 images).

Superiority over baseline models: When compared with traditional machine learning algorithms such as Support Vector Machine and Random Forest, the CNN consistently outperformed them across all metrics, with differences in accuracy ranging from 7 to 15 percentage points. This substantiates the claim that deep learning architectures are particularly well-suited for tasks involving complex, nonlinear, and high-dimensional image data, such as recognizing satisfaction and emotions in restaurant settings.

Managerial and practical implications: Beyond technical validation, these results demonstrate the feasibility of deploying CNN-based systems as complementary tools for service quality monitoring. By providing near-real-time indicators of customer satisfaction, such systems could support restaurant managers in making informed decisions regarding staffing, process design, and personalized service. However, the findings also caution against overreliance on facial analysis alone, emphasizing the need for ethical safeguards and the integration of complementary measurement instruments.

The results support H1, confirming that CNNs significantly outperform SVM and Random Forest models in classifying customer satisfaction based on facial expressions. They also provide empirical support for H2, as the detected expressions of satisfaction and dissatisfaction correspond to theoretical dimensions of service quality described in SERVQUAL and Expectation–Disconfirmation Theory. Together, these findings validate the theoretical and methodological premises of the study and set the basis for discussing broader implications in

Section 5.

5. Discussion

5.1. General Analysis of Results

This study also deepens the theoretical understanding of how customers’ emotional responses, observable through facial expressions, correspond to established dimensions of service quality. Within the SERVQUAL framework, positive affective cues—such as smiling, eye contact, and relaxed posture—can be interpreted as behavioral manifestations of responsiveness and empathy, reflecting customers’ perception that staff were attentive and caring. Similarly, expressions of dissatisfaction often correlate with disruptions in perceived reliability or assurance, revealing breakdowns in expected service performance. From the lens of the Expectation–Disconfirmation Theory (

Oliver, 1980), the CNN’s binary classification effectively captures the outcome of this disconfirmation process: satisfied customers exhibit positive non-verbal reactions when perceived performance exceeds expectations, whereas dissatisfied customers display negative or neutral affect when expectations are unmet.

By linking CNN-based emotion recognition to these theoretical constructs, the study demonstrates that deep learning models can serve as real-time, behavioral extensions of classical satisfaction measurement frameworks. This strengthens the conceptual bridge between technological innovation and service theory, showing that automated facial analysis does not replace subjective evaluation but rather translates perceptual and emotional responses into quantifiable, theory-consistent indicators.

The implemented convolutional neural network (CNN) achieved robust and balanced performance, with overall accuracy above 93%, a recall of 92.8%, and an F1-score of 91%. These outcomes confirm the suitability of deep architectures for automatically interpreting facial expressions in restaurant settings, aligning with previous findings that emphasize the robustness of CNNs under real-world conditions (

LeCun et al., 2015;

Yildirim et al., 2023;

Pereira et al., 2024). In comparative terms, the CNN consistently outperformed traditional machine learning models such as SVM and Random Forest, corroborating prior evidence that deep learning excels at extracting nonlinear and high-dimensional patterns from visual data (

Sun & Sun, 2021;

J. Chen et al., 2022).

Error analysis revealed that misclassifications were concentrated in ambiguous cases, such as neutral or mixed-affect expressions. This limitation reflects the difficulty of operationalizing “satisfaction” using static visual cues alone, suggesting that multimodal approaches—combining images with text, voice, or behavioral data—may enhance analytical robustness (

Zhang et al., 2022;

Vargas-Calderón et al., 2021). The high discriminative power observed (AUC = 0.93) further validates the methodological decision to employ transfer learning with pre-trained weights, which enabled strong predictive performance despite the moderate dataset size (

Yu et al., 2022).

The results obtained provide strong empirical support for the first two hypotheses proposed in this study. Specifically, the superior performance of CNNs over traditional machine learning models validates H1, confirming that deep learning architectures are more effective for classifying customer satisfaction based on facial expressions in real service contexts. Likewise, the observed correspondence between emotional responses and the theoretical dimensions of service quality (e.g., responsiveness, empathy, and reliability) supports H2, demonstrating that CNN-based classifications align with established conceptual frameworks such as SERVQUAL and the Expectation–Disconfirmation Theory. These findings strengthen the theoretical foundation for integrating neural methods into customer satisfaction research.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to the ongoing debate on modernizing customer satisfaction (CS) measurement in hospitality by bridging classical instruments and data-driven neural methods. Traditional approaches such as SERVQUAL, SERVPERF, and the American Customer Satisfaction Index remain indispensable for capturing declared perceptions and diagnosing service attributes (

Parasuraman et al., 1988;

Cronin & Taylor, 1992;

Fornell et al., 1996;

Praditbatuga et al., 2022). However, their reliance on declarative responses and delayed feedback constrains responsiveness in dynamic environments (

Bonfanti et al., 2023).

By contrast, CNNs and other neural architectures expand the analytical capacity of CS research by integrating implicit, real-time signals from facial images, complementing the explanatory depth of survey-based models (

Mariani et al., 2023). The evidence provided here reinforces the argument that hybrid systems—blending traditional instruments with neural analytics—offer a more comprehensive and context-sensitive view of customer experiences. Furthermore, the misclassification patterns observed highlight the theoretical need to integrate multimodality and explainability into satisfaction research (

Chutia et al., 2024;

Limna, 2023), thereby advancing discussions on the intersection between artificial intelligence, service quality, and human behavior.

In addition, the validation of H3 highlights that CNN-based methods can serve as a non-intrusive and ethically responsible complement to traditional survey instruments. By bridging declarative and behavioral data, they contribute to a hybrid understanding of satisfaction that integrates explicit perceptions with implicit emotional responses. This supports the broader theoretical proposition that artificial intelligence should augment—not replace—human-centered models of service quality evaluation.

5.3. Practical and Managerial Implications

From a managerial perspective, CNN-based systems present significant opportunities for real-time service monitoring. Beyond constructing dashboards that display satisfaction levels per shift or restaurant zone, these systems could support predictive functions such as identifying dissatisfaction peaks, segmenting customers by satisfaction profiles, or generating alerts to guide staff allocation. These applications align with the growing emphasis on data-driven decision-making in hospitality and tourism (

Duan et al., 2019;

Yang et al., 2024).

However, the adoption of AI-driven monitoring systems must be carefully managed to avoid perceptions of surveillance. As highlighted by

Morosan (

2022), customer mistrust may arise if technologies are perceived as intrusive. To mitigate this risk, implementation strategies should prioritize transparency, obtain explicit consent, employ robust anonymization methods, and ensure compliance with local data protection regulations. When framed as tools to enhance service quality rather than as surveillance mechanisms, CNN-based systems can strengthen trust and contribute to the co-creation of personalized experiences.

From an ethical standpoint, the deployment of AI-based monitoring systems in hospitality requires careful governance. Transparency, informed consent, and clear communication with customers are essential to prevent perceptions of surveillance or data misuse. The findings of this study reaffirm that strong ethical safeguards must accompany technological innovation in service quality assessment. This ensures that facial recognition is implemented responsibly, with anonymization and limited data retention as non-negotiable principles. Future research should continue to explore frameworks for responsible AI adoption in hospitality, balancing predictive accuracy with privacy, fairness, and human-centered service values.

In this regard, it is important to clarify that the proposed CNN model does not judge or classify people based on their physical appearance or demographic traits. Instead, it analyzes transient emotional expressions that are anonymized and unlinked to any personal identifiers. The objective is exclusively analytical—to capture collective patterns of satisfaction in real service contexts and support managerial decision-making, not to evaluate or profile individuals. The system operates under voluntary participation and informed consent, with all data processed locally and destroyed after analysis. By emphasizing these safeguards, the study aligns with international ethical standards, including the 2013 revision of the Declaration of Helsinki. It reinforces that AI-driven facial analysis in hospitality must always serve as a supportive tool for improving service quality, never as a mechanism for surveillance or discrimination.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations. First, the dataset, although sizable (2969 images), was collected in a single establishment located in Quito, Ecuador. This context-specific setting may limit the external validity of the findings, as customer behavior, expressiveness, and service expectations can vary across regions and cultures. Cultural display rules influence how emotions are expressed facially and how satisfaction or dissatisfaction is manifested, meaning that similar service interactions might evoke different visible responses in other sociocultural environments. Second, the satisfaction labels were derived from binary self-reporting, which may not capture the full richness of the consumption experience. Third, the analysis focused solely on static facial images, omitting complementary signals such as body language, tone of voice, or the quality of customer–staff interaction. Finally, deep neural networks pose inherent challenges regarding interpretability and potential biases linked to demographic or contextual factors. Future research should therefore replicate this study across multiple restaurant types (e.g., casual dining, fine dining, quick service) and in different cultural or geographic contexts to validate the robustness of the model and test its generalizability. Cross-country comparisons could also help refine the CNN’s interpretive accuracy by incorporating culturally adaptive emotion classifiers and expanding the dataset to represent diverse facial expressions and service dynamics.

Future research should address these limitations by expanding the dataset to include multiple restaurant types and geographic contexts, thereby enhancing external validity. Incorporating multimodal approaches that integrate text (e.g., online reviews), images, and behavioral signals could provide a more holistic measurement of satisfaction. Moreover, comparing different neural architectures—such as vision transformers, hybrid CNN–RNN models, or transformer-based systems—may further improve accuracy and explainability (

Yu et al., 2022;

Zafar & Zafar, 2025). Ultimately, advancing explainable AI (XAI) frameworks and evaluating customer perceptions of AI adoption will be crucial for ensuring both managerial confidence and ethical legitimacy in the hospitality industry.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that convolutional neural networks (CNNs) offer a technically robust and non-intrusive alternative for measuring customer satisfaction in the restaurant sector. By analyzing a validated dataset of 2969 images collected in a real-world service environment, the proposed model achieved strong performance, exceeding 93% in overall accuracy, with a recall of 92.8% and an F1-score of 91%, consistently outperforming traditional statistical and machine learning approaches, such as Support Vector Machines and Random Forest. These results confirm the capacity of CNNs to automatically detect satisfaction and dissatisfaction through facial expressions, thereby expanding the methodological toolkit available to hospitality researchers and practitioners.

Beyond technical feasibility, the findings highlight that CNN-based systems can complement rather than replace traditional survey-based instruments such as SERVQUAL or SERVPERF. Classical models remain indispensable for capturing declared perceptions, motivations, and qualitative insights, whereas CNNs enable real-time monitoring and mitigate recall and social desirability biases. Together, these approaches provide a more holistic view of customer experience, particularly valuable in dynamic and high-contact service settings such as restaurants.

From a managerial standpoint, neural analytics can serve as a strategic tool for immediate decision-making. By providing continuous indicators of satisfaction, CNN-based systems can support managers in adjusting staffing levels, redesigning processes, or tailoring gastronomic experiences in near real time. However, their adoption also raises important challenges related to model explainability, external validity across diverse contexts, and compliance with ethical and regulatory frameworks regarding the use of personal data. Addressing these issues is critical to ensuring responsible deployment and maintaining customer trust.

In summary, this research provides empirical evidence and methodological insights into the modernization of satisfaction measurement in the hospitality industry. The integration of deep learning into service evaluation does not displace established methods but rather complements them, paving the way for hybrid systems that combine explicit and implicit signals. Future research should explore multimodal approaches, larger and more diverse datasets, and explainable AI techniques to further enhance both the accuracy and the ethical legitimacy of AI-driven customer satisfaction management in gastronomy and tourism.