Applying the SOR Framework to Food Truck Dining: Consumption Needs, Perceptions, and Behavioral Intentions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

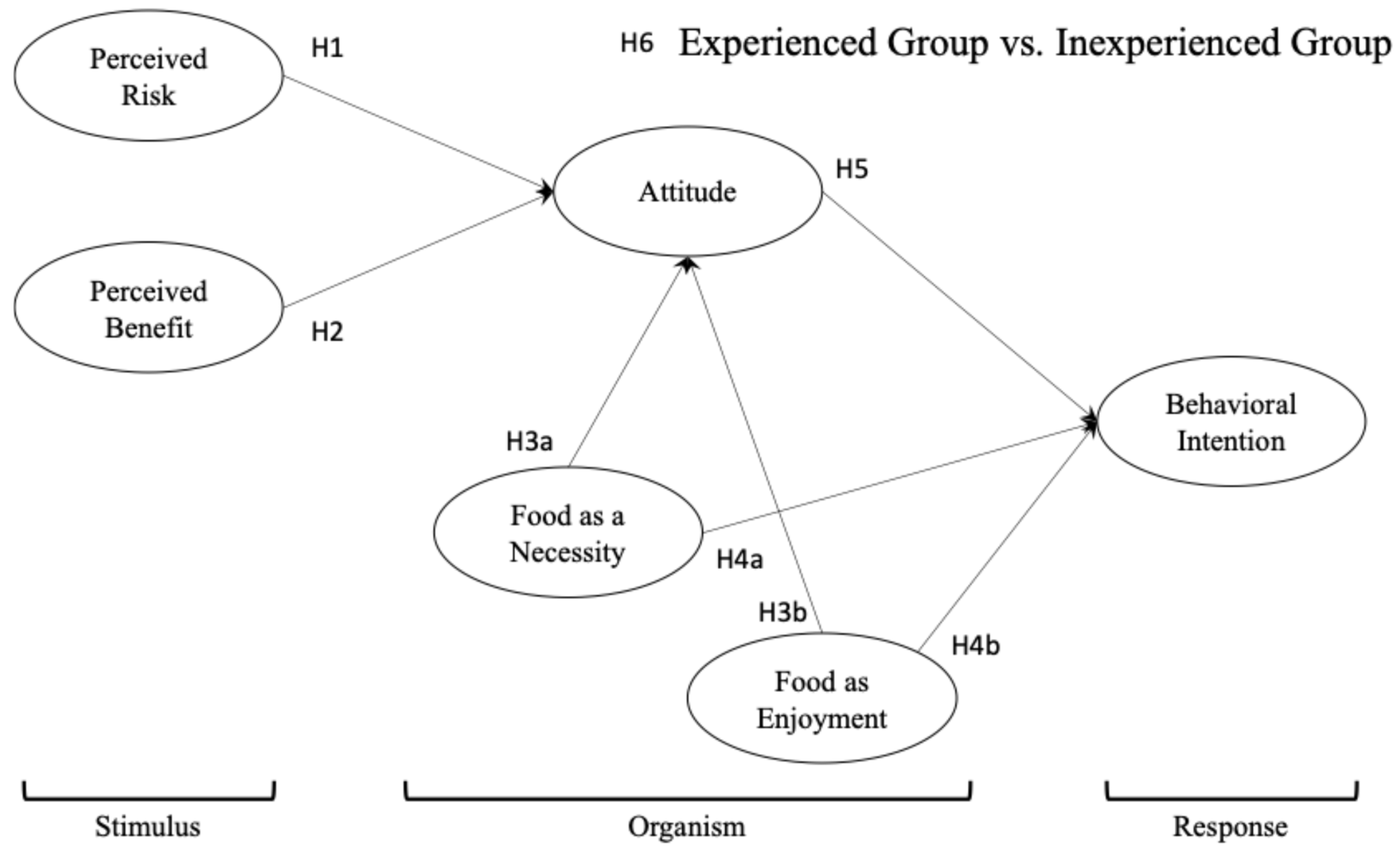

2.1. SOR Model as the Theoretical Foundation

2.2. Perceptions of Food Trucks as Stimuli

2.2.1. Perceived Risks

2.2.2. Perceived Benefits

2.3. Consumers’ Internal States and Traits as an Organism

2.3.1. Food Consumption Needs

2.3.2. Attitude

2.4. Behavioral Intention as a Response

2.5. Moderating Role of Prior Experience

3. Methodology

3.1. Survey Questionnaire

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Characteristics

4.2. Validity and Reliability

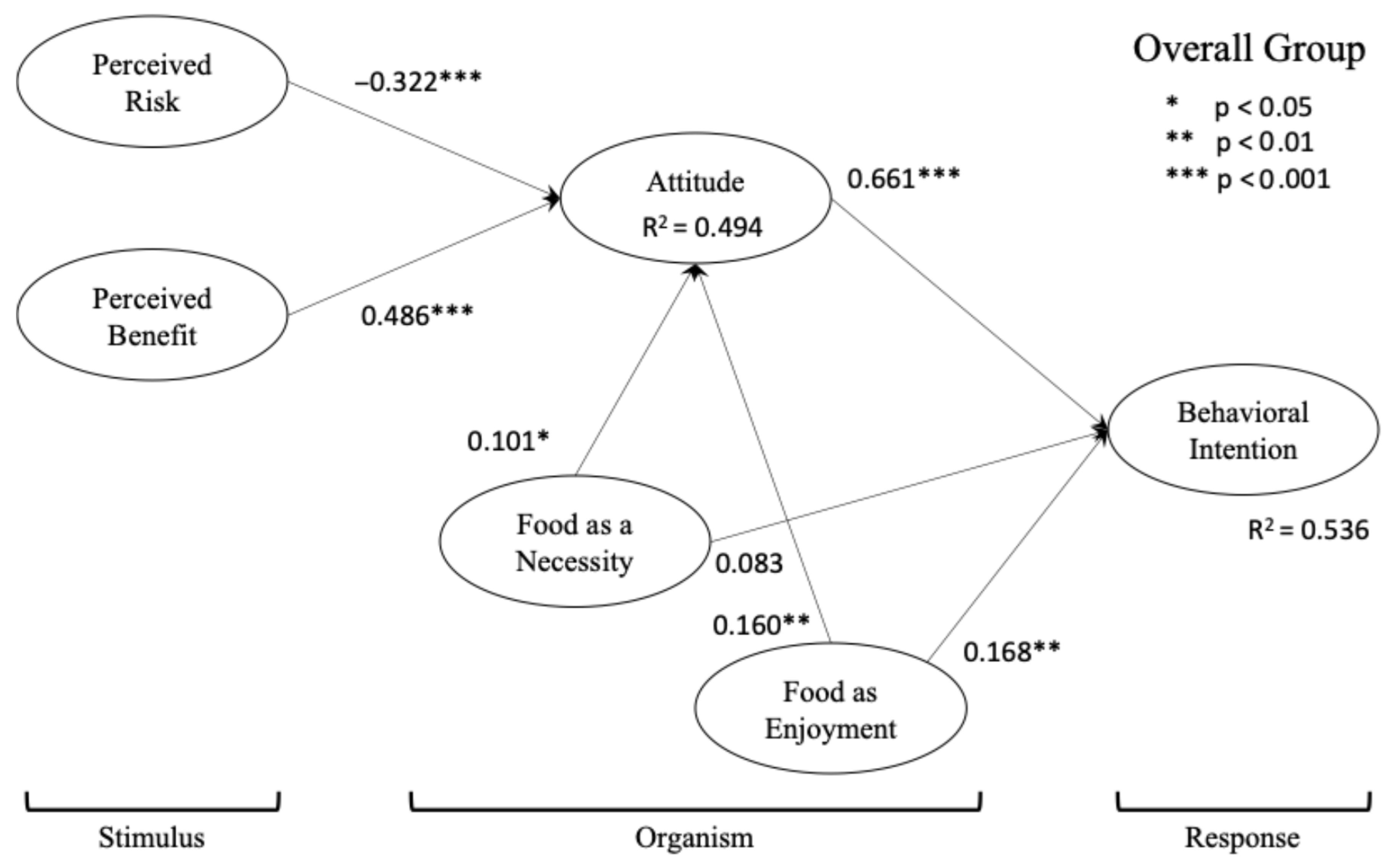

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

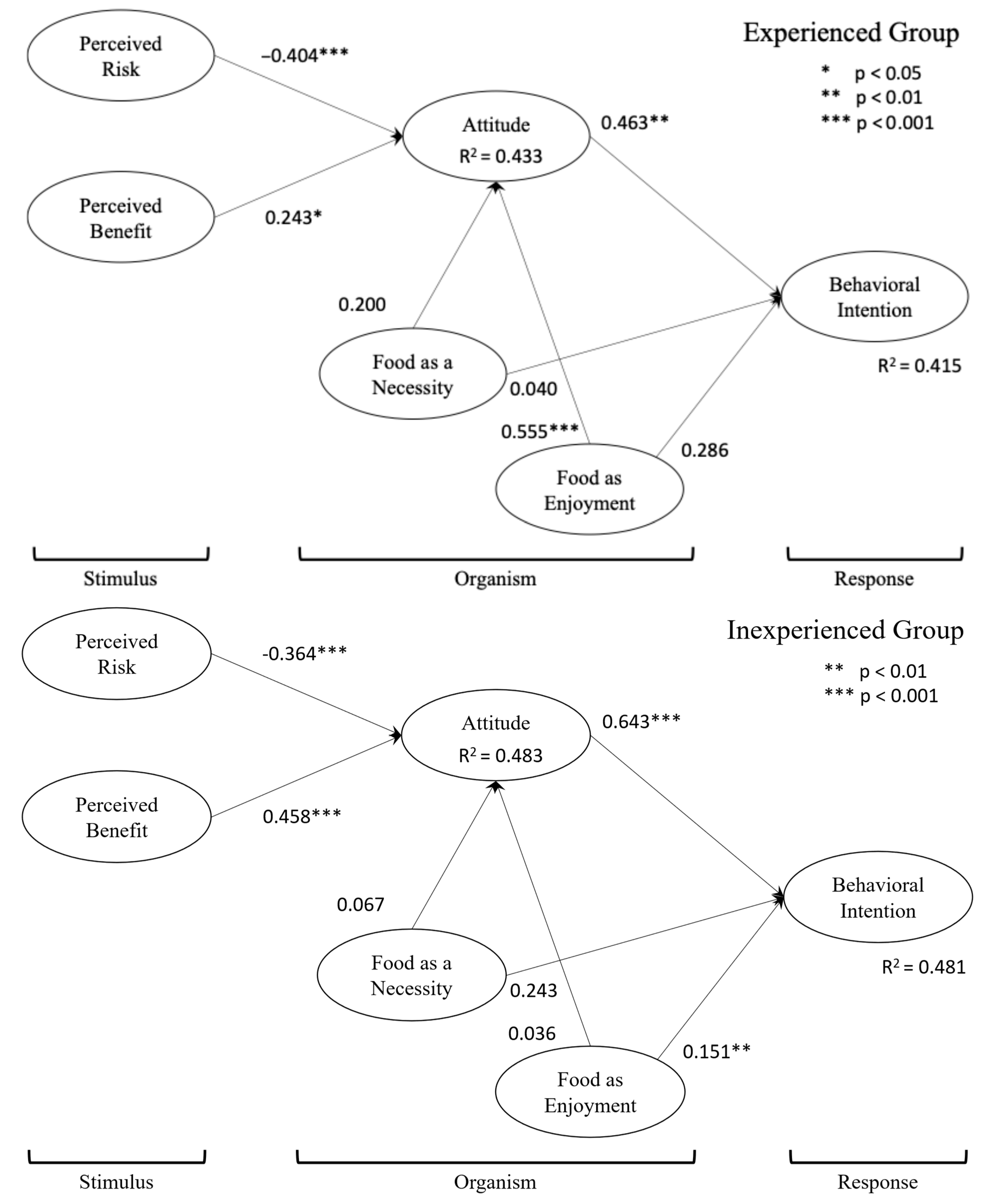

4.4. Group Differences

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ajzen, I. (1985). From intention to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In J. Kuhl, & J. Beckmann (Eds.), Action control: From cognition to behavior (pp. 11–39). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. (1988). Attitudes, personality, and behavior. Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, J. W., & Hutchinson, J. W. (1987). Dimensions of consumer expertise. Journal of Consumer Research, 13, 411–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, E. M., & Trafton, J. G. (2002). Memory for goals: An activation-based model. Cognitive Science, 26(1), 39–83. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, J., & Choe, Y. (2025). Social context and risk perceptions in food truck experiences. Tourism Analysis, 30(3), 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R. P. (1992). The self-regulation of attitudes, intentions, and behavior. Social Psychology Quarterly, 55, 178–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R. A. (1960). Consumer behavior as risk taking. In D. F. Cox (Ed.), Risk taking and information handling in consumer behavior (pp. 23–33). Harvard University, Graduate School of Business Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Bäckström, A., Pirttilä-Backman, A. M., & Tuorila, H. (2004). Willingness to try new foods as predicted by social representations and attitude and trait scales. Appetite, 43(1), 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, L. L., Seiders, K., & Grewal, D. (2002). Understanding service convenience. Journal of Marketing, 66(3), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G., So, K. K. F., Hu, X., & Poomchaisuwan, M. (2022). Travel for affection: A stimulus-organism-response model of honeymoon tourism experiences. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 46(6), 1187–1219. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H., & Kandampully, J. (2019). The effect of atmosphere on customer engagement in upscale hotels: An application of SOR paradigm. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 77, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J., Lee, A., & Ok, C. (2013). The effects of consumers’ perceived risk and benefit on attitude and behavioral intention: A study of street food. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 30(3), 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chosun News. (2024, July 10). Chicken restaurant posting daily fryer cleaning photos… ‘cleanliness’ reputation leads to increased sales. Chosun. Available online: https://www.chosun.com/national/national_general/2024/07/10/SVU2LHZOCJFD3PBIV7W6MGK2KU/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Curran, P. G. (2016). Methods for the detection of carelessly invalid responses in survey data. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 66, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z., Mo, X., & Liu, S. (2014). Comparison of the middle-aged and older users’ adoption of mobile health services in China. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 83(3), 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, J. M., & Lynch, J. G. (1988). Self-generated validity and other effects of measurement on belief, attitude, intention, and behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 73(3), 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H., Hwang, J., Lee, M. J., & Kim, J. (2019). Word-of-mouth, buying, and sacrifice intentions for eco-cruises: Exploring the function of norm activation and value-attitude-behavior. Tourism Management, 70, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, M. R., Dodds, R., Deen, G., Lubana, A., Munson, J., & Quigley, S. (2018). Local and organic food on wheels: Exploring the use of local and organic food in the food truck industry. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 21(5), 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer, P. M., & Kahle, L. R. (1988). A structural equation test of the value-attitude-behavior hierarchy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(4), 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBISWorld. (2023). Industry report: Food trucks in the US. IBISWorld. Available online: https://www.lee-associates.com/elee/sandiego/LeeLandTeam/79315Highway111/OD4322%20Food%20Trucks%20in%20the%20US%20Industry%20Report.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Jacoby, J., & Kaplan, L. B. (1972, November 2–5). The components of perceived risk. Third Annual Conference (pp. 382–393), Chicago, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, S. S., & Namkung, Y. (2009). Perceived quality, emotions, and behavioral intentions: Application of an extended Mehrabian–Russell model to restaurants. Journal of Business Research, 62(4), 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, J., Kang, J., & Arendt, S. W. (2014). The effects of health value on healthful food selection intention at restaurants: Considering the role of attitudes toward taste and healthfulness of healthful foods. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 42, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, S. H. (2020). The effects of perceived risk, brand credibility and past experience on purchase intention in the Airbnb context. Sustainability, 12(12), 5212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J., Jun, J., & Arendt, S. W. (2015). Understanding customers’ healthy food choices at casual dining restaurants: Using the value–attitude–behavior model. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 48, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karisto, A., Prättälä, R., & Berg, M. A. (1993). The good, the bad, and the ugly. Differences and changes in health related lifestyles. In U. Kjærnes, L. Holm, M. Ekström, E. Fürst, & R. Prättälä (Eds.), Regulating markets, regulating people. On food and nutrition policy (pp. 185–204). Novus. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D. J., Ferrin, D. L., & Rao, H. R. (2008). A trust-based consumer decision-making model in electronic commerce: The role of trust, perceived risk, and their antecedents. Decision Support Systems, 44(2), 544–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. H., Hu, F., Wen, J., & Hou, H. (2024). Understanding tourists’ dining behaviors at traditional Chinese nutraceutical restaurants. Anatolia, 35(3), 528–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W. G., & Moon, Y. J. (2009). Customers’ cognitive, emotional, and actionable response to the servicescape: A test of the moderating effect of the restaurant type. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28(1), 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutroumanis, E. (2015). New York City, New Haven, and the new mobile food trends: An analysis of local law and culture in response to the reawakening of mobile food. Connecticut Law Review, 48, 233–262. [Google Scholar]

- Lazaridis, P., & Drichoutis, A. C. (2005). Food consumption issues in the 21st century. In P. Soldatos, & S. Rozakis (Eds.), The food industry in Europe (pp. 21–33). Agricultural University of Athens. [Google Scholar]

- Loh, Z., & Hassan, S. H. (2022). Consumers’ attitudes, perceived risks and perceived benefits towards repurchase intention of food truck products. British Food Journal, 124(4), 1314–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, I., Petruzzelli, A. M., & Panniello, U. (2023). Innovating agri-food business models after the COVID-19 pandemic: The impact of digital technologies on the value creation and value capture mechanisms. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 190, 122404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, K. (2009). Food truck nation. The Wall Street Journal. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052970204456604574201934018170554 (accessed on 31 January 2019).

- Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1974). An approach to environmental psychology. The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R. L. (1999). Whence consumer loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 63(4_suppl1), 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M. C., & Bartels, J. (2013). Development and cross-cultural validation of a shortened social representations scale of new foods. Food Quality and Preference, 28(1), 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peek, S. (2023). How to start a food truck business. Business news daily. Available online: https://www.businessnewsdaily.com/9237-how-to-start-food-truck-business.html (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Perugini, M., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2001). The role of desires and anticipated emotions in goal-directed behaviours: Broadening and deepening the theory of planned behaviour. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(1), 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, D. (2014). Food Truck Fever: A spatio-political analysis of food truck activity in Kansas City, Missouri [Master’s thesis, Kansas State University]. Available online: https://krex.k-state.edu/items/389b7af1-50ad-4068-b256-7a9f15d26a07 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 19, pp. 123–205). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Petty, R. E., Cacioppo, J. T., & Schumann, D. (1983). Central and peripheral routes to advertising effectiveness: The moderating role of involvement. Journal of Consumer Research, 10(2), 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(1), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senauer, B. (2001). The food consumer in the 21st century: New research perspectives (Working paper). Department of Applied Economics, University of Minnesota. [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran, P., & Webb, T. L. (2016). The intention–behavior gap. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10(9), 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y. H., Im, J., & Severt, K. (2020). Qualitative assessment of key beliefs in regards to consumers’ food truck visits. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 21(2), 129–145. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Y. H., Kim, H., & Severt, K. (2019). Consumer values and service quality perceptions of food truck experiences. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 79, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y. H., Moon, H., Jung, S. E., & Severt, K. (2017). The effect of environmental values and attitudes on consumer willingness to pay more for organic menus: A value-attitude-behavior approach. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 33, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinker, I. (2003). Street foods: Traditional microenterprise in a modernizing world. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, 16(3), 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B., & Aarts, H. (1999). Habit, attitude, and planned behaviour: Is habit an empty construct or an interesting case of goal-directed automaticity? European Review of Social Psychology, 10(1), 101–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, K. E., Spangenberg, E. R., & Grohmann, B. (2003). Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian dimensions of consumer attitude. Journal of Marketing Research, 40(3), 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Berbekova, A., Uysal, M., & Wang, J. (2024). Emotional solidarity and co-creation of experience as determinants of environmentally responsible behavior: A stimulus-organism-response theory perspective. Journal of Travel Research, 63(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. L., & Li, E. Y. (2018). Marketing mix, customer value, and customer loyalty in social commerce: A stimulus-organism-response perspective. Internet Research, 28(1), 74–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B., & Chung, Y. (2018). Consumer attitude and visit intention toward food-trucks: Targeting millennials. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 21(2), 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). The behavioral consequences of service quality. Journal of Marketing, 60(2), 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Items | Coef. |

|---|---|---|

| Food as a necessity | I do not care what I eat, as long as I am not hungry. | 0.811 |

| I do not care how my food is produced. | 0.798 | |

| It makes no difference to me what kind of food is served at parties. | 0.791 | |

| I do not really need information about new foods. | 0.764 | |

| Food as enjoyment | Eating is very important to me. | 0.825 |

| Delicious food is an essential part of my daily life. | 0.849 | |

| Eating is a highlight of my day. | 0.792 | |

| I treat myself to something really delicious. | 0.762 | |

| Perceived risk | Improper food storage | 0.920 |

| Not using fresh ingredients | 0.856 | |

| Unsanitary conditions | 0.898 | |

| Insufficient water supply | 0.776 | |

| Poor food quality | 0.839 | |

| High risk for food poisoning | 0.894 | |

| Perceived benefits | Easy accessibility | 0.925 |

| Eating convenience | 0.940 | |

| Fast or prompt service | 0.881 | |

| Attitude | Disadvantageous vs. advantageous | 0.806 |

| Foolish vs. wise | 0.814 | |

| Unpleasant vs. pleasant | 0.919 | |

| Unattractive vs. attractive | 0.914 | |

| Behavioral intention | I am planning to visit a food truck when eating out in the future. | 0.927 |

| I intend to visit a food truck when eating out in the future. | 0.959 | |

| I will make an effort to visit a food truck when eating out in the future. | 0.880 |

| Correlations Among Constructs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Food as a necessity (1) | 0.792 a | |||||

| Food as enjoyment (2) | −0.315 | 0.809 | ||||

| Perceived risk (3) | 0.030 | −0.043 | 0.865 | |||

| Perceived benefits (4) | 0.047 | 0.298 | −0.232 | 0.916 | ||

| Attitude toward food trucks (5) | 0.067 | 0.291 | −0.438 | 0.596 | 0.869 | |

| Future behavioral intention (6) | 0.072 | 0.328 | −0.295 | 0.648 | 0.702 | 0.922 |

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.869 | 0.879 | 0.946 | 0.939 | 0.921 | 0.945 |

| Construct reliability | 0.870 | 0.882 | 0.947 | 0.940 | 0.924 | 0.944 |

| Average variance explained | 0.627 | 0.655 | 0.748 | 0.839 | 0.754 | 0.850 |

| Maximum shared variance | 0.099 | 0.108 | 0.192 | 0.420 | 0.493 | 0.493 |

| Average shared variance | 0.022 | 0.076 | 0.067 | 0.184 | 0.226 | 0.223 |

| Model Fit Measures | Model Differences | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | p | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | SRMR | AIC | BIC | p | ||||

| Separate groups | ||||||||||||

| Visitor group | 298.28 | 237 | 0.004 | 0.053 | 0.960 | 0.953 | 0.064 | 8478.16 | 8654.29 | |||

| Non-visitor group | 283.79 | 237 | 0.020 | 0.033 | 0.987 | 0.985 | 0.041 | 19,366.11 | 29,593.74 | |||

| Measurement invariant test | ||||||||||||

| Configural invariance | 581.26 | 474 | >0.001 | 0.040 | 0.980 | 0.977 | 0.046 | 27,940.27 | 28,632.59 | |||

| Metric invariance | 601.05 | 492 | >0.001 | 0.040 | 0.980 | 0.977 | 0.048 | 27,929.35 | 28,550.05 | 19.58 | 18 | 0.357 |

| Full scalar invariance | 636.75 | 510 | >0.001 | 0.042 | 0.977 | 0.975 | 0.049 | 27,927.78 | 28,476.86 | 48.52 | 18 | >0.001 |

| Partial scalar invariance | 616.01 | 507 | >0.001 | 0.039 | 0.980 | 0.978 | 0.049 | 27,912.12 | 28,473.14 | 13.43 | 15 | 0.569 |

| Strict factorial invariance | 640.52 | 531 | >0.001 | 0.039 | 0.979 | 0.978 | 0.049 | 27,941.48 | 28,407.01 | 26.82 | 24 | 0.313 |

| Path | Experienced Group | Inexperienced Group | Difference Test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Coefficient | |||||||

| Perceived risk | → | Attitude | −0.404 | *** | −0.364 | *** | = 1.990 | |

| Perceived benefit | → | Attitude | 0.243 | * | 0.458 | *** | = 0.078 | |

| Food as a necessity | → | Attitude | 0.2 | 0.067 | = 1.039 | |||

| Food as enjoyment | → | Attitude | 0.555 | *** | 0.036 | = 6.663 | *** | |

| Attitude | → | Behavioral intention | 0.463 | ** | 0.643 | *** | = 3.651 | † |

| Food as a necessity | → | Behavioral intention | 0.04 | 0.069 | = 0.357 | |||

| Food as enjoyment | → | Behavioral intention | 0.286 | 0.151 | ** | = 0.903 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baek, J.; Choe, Y. Applying the SOR Framework to Food Truck Dining: Consumption Needs, Perceptions, and Behavioral Intentions. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050265

Baek J, Choe Y. Applying the SOR Framework to Food Truck Dining: Consumption Needs, Perceptions, and Behavioral Intentions. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(5):265. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050265

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaek, Jooa, and Yeongbae Choe. 2025. "Applying the SOR Framework to Food Truck Dining: Consumption Needs, Perceptions, and Behavioral Intentions" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 5: 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050265

APA StyleBaek, J., & Choe, Y. (2025). Applying the SOR Framework to Food Truck Dining: Consumption Needs, Perceptions, and Behavioral Intentions. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(5), 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050265