Experiential Marketing Through Service Quality Antecedents: Customer Experience as a Driver of Satisfaction and Revisit Intentions in South African Restaurants

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Quality Antecedents

2.2. Experiences

2.3. Satisfaction

2.4. Behavioural Outcomes

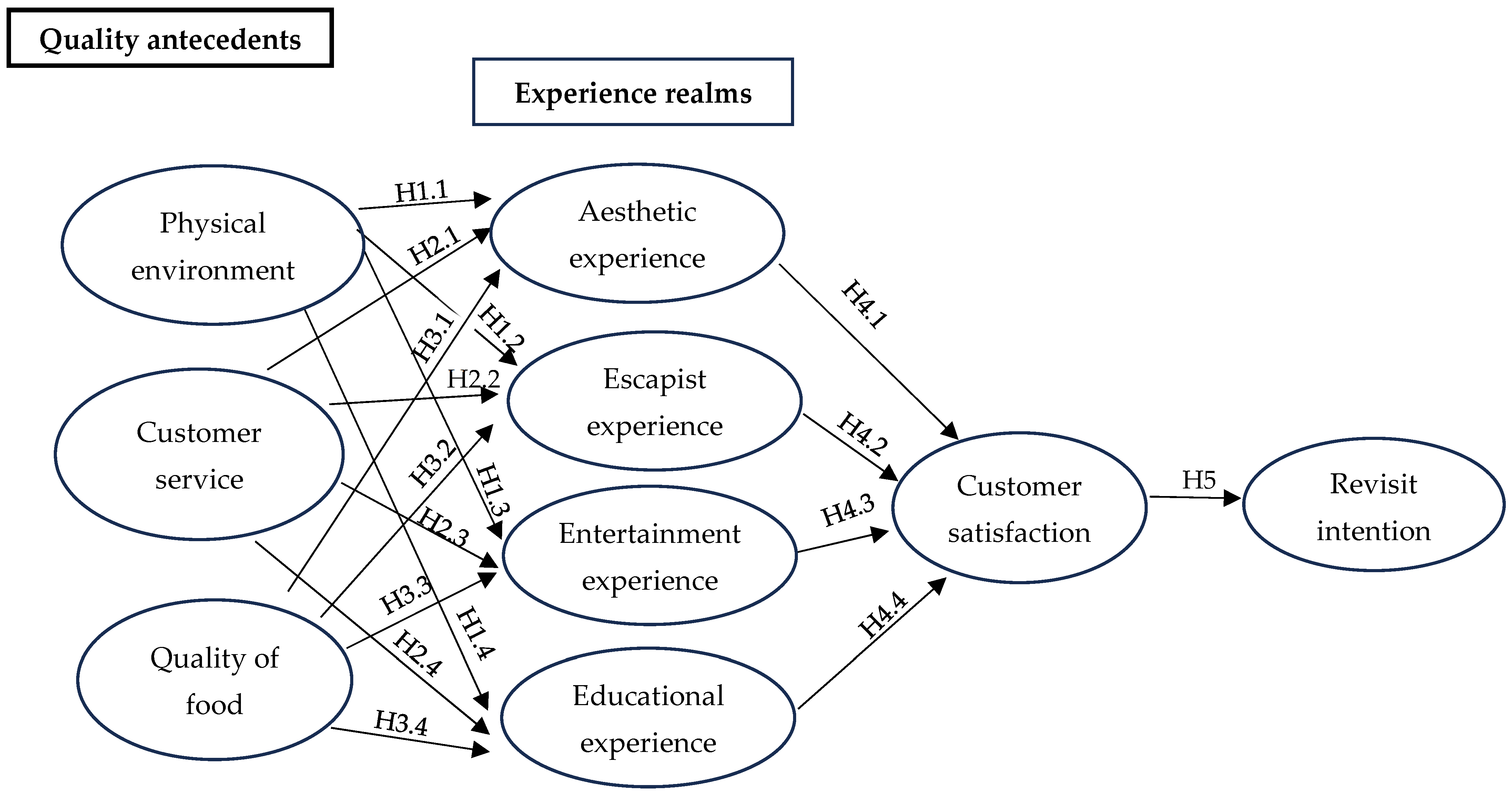

2.4.1. The Influence of the Physical Environment on Experiences

2.4.2. The Influence of Customer Service on Experiences

2.4.3. The Influence of Food Quality on Experiences

2.4.4. The Influence of Customer Experiences on Customer Satisfaction

2.4.5. The Influence of Customer Satisfaction on Revisit Intentions

3. Methodology

3.1. Population and Sampling

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Measuring Instrument

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Sample Profile

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

4.3. Inferential Statistics

4.4. Reporting Results of Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

Managerial Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organisational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, C. M., Rao, M. S., & Swarnalatha, J. (2022). Relationship between service interaction, customer experience quality, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty: Serial mediation approach. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 6(8), 1940–1950. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, B. J., Gardi, B., Othman, B. J., Ahmed, S. A., Ismael, N. B., Hamza, P. A., Aziz, H. M., Sabir, B. Y., Sorguli, S., & Anwar, G. (2021). Hotel service quality: The impact of service quality on customer satisfaction in hospitality. International Journal of Engineering, Business and Management, 5(3), 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rifat, A., & Tasnim, R. (2019). Factors influencing customers’ selection of restaurants in Dhaka, Bangladesh. The Business & Management Review, 10(5), 186–198. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, C. (2019). The p value and statistical significance: Misunderstandings, explanations, challenges, and alternatives. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 41(3), 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anggraeni, R., Hendrawan, D., & Huang, Y. W. (2020). The impact of theme restaurant servicescape on consumers’ value and purchase intention. In Asian forum of business education (pp. 226–232). Atlantis Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgihan, A., Seo, S., & Choi, J. (2017). Identifying restaurant satisfiers and dissatisfiers: Suggestions from online reviews. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 27(5), 601–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A., & Verma, R. K. (2022). Augmenting service quality dimensions: Mediation of image in the Indian restaurant industry. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 26(3), 496–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfanti, A., Bagnato, G., & Vigolo, V. (2025). The contribution of sustainable practices to the creation of memorable customer experience: Empirical evidence from Michelin Green Star restaurants. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 126, 104110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakus, J. J., Schmitt, B. H., & Zarantonello, L. (2009). Brand experience: What is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 73(3), 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassel, E., Jacobs, B., & Graham, M. (2021). Effects of the four realms of experience and pleasurable experiences on consumer intention to patronise pop-up stores. Journal of Consumer Sciences, 49, 78–93. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. C., Tsui, P. L., Chen, H. I., Tseng, H. L., & Lee, C. S. (2020). A dining table without food: The floral experience at ethnic fine dining restaurants. British Food Journal, 122(6), 1819–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieck, M. C., & Han, D. I. D. (2022). The role of immersive technology in customer experience management. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 30(1), 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EHL Insights. (2025). Key hospitality data & industry statistics to watch for 2025. Available online: https://hospitalityinsights.ehl.edu/hospitality-industry-statistics (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- El-Said, O. A., Smith, M., & Al Ghafri, W. (2021). Antecedents and outcomes of dining experience satisfaction in ethnic restaurants: The moderating role of food neophobia. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 30(7), 799–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkmen, E., & Hancer, M. (2019). Building brand relationship for restaurants: An examination of other customers, brand image, trust, and restaurant attributes. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(3), 1469–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L. H., Gao, L., Liu, X., Zhao, S. H., Mu, H. T., Li, Z., Shi, L., Wang, L. L., Jia, X. L., Ha, M., & Lou, F. G. (2017). Patients’ perceptions of service quality in China: An investigation using the SERVQUAL model. PLoS ONE, 12(12), e0190123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitts, D. A. (2022). Point and interval estimates for a standardized mean difference in paired sample designs using a pooled standard deviation. The Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 18(3), 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L., Melero-Polo, I., & Sese, F. J. (2020). Customer equity drivers, customer experience quality, and customer profitability in banking services: The moderating role of social influence. Journal of Service Research, 23(2), 174–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J. J., & Kwon, K. J. (2018). The remodeling of brand image of the time-honored restaurant brand of Wuhan based on emotional design in the age of experience economy. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, 180, 233–236. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Howard, M. C., & Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S., & Yoon, J. (2020). Cultural intelligence on perceived value and satisfaction of ethnic minority groups’ restaurant experiences in Korea. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 18(3), 310–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, D., Bismo, A., & Basri, A. R. (2020). The effect of food quality and service quality towards customer satisfaction and repurchase intention (case study of hot plate restaurants). Journal of Management Business, 10(01), 01–09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, F. D., & Ulmer, M. W. (2022). Supervised learning for arrival time estimations in restaurant meal delivery. Transportation Science, 56(4), 1058–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, J. S., & Hsu, H. (2021). Esthetic dining experience: The relations among aesthetic stimulation, pleasantness, memorable experience, and behavioral intentions. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 30(4), 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J., Abbas, J., Joo, K., Choo, S. W., & Hyun, S. S. (2022). The effects of different types of service providers on the experience economy, brand attitude, and brand loyalty in the restaurant industry. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(6), 3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D. L., Gillaspy, J. A., Jr., & Purc-Stephenson, R. (2009). Reporting practices in confirmatory factor analysis: An overview and some recommendations. Psychological Methods, 14(1), 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, M., & Shin, H. H. (2020). Tourists’ experiences with smart tourism technology at smart destinations and their behavior intentions. Journal of Travel Research, 59(8), 1464–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D., DiPietro, R. B., & Fan, A. (2020). The impact of customer controllability and service recovery type on customer satisfaction and consequent behavior intentions. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 29(1), 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T., Ineson, E. M., Kim, M., & Yap, M. H. (2015). Influence of festival attribute qualities on Slow Food tourists’ experience, satisfaction level, and revisit intention: The case of the Mold Food and Drink Festival. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 21(3), 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagöz, H. A., Demirciftci, T., & Erkmen, E. (2022). Local restaurants’ effect on tourist experience: A case from Istanbul. Journal of Economy Culture and Society, 65, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasongo, L. (2023). Impact of the hospitality and tourism industry on social economic development in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). International Journal of Modern Hospitality and Tourism, 3(1), 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I., Garg, R. J., & Rahman, Z. (2015). Customer service experience in hotel operations: An empirical analysis. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 189, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S., Choe, J. Y., King, B., Oh, M., & Otoo, F. E. (2022). Tourist perceptions of local food: A mapping of cultural values. International Journal of Tourism Research, 24(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S., Ham, S., Moon, H., Chua, B. L., & Han, H. (2019). Experience, brand prestige, perceived value (functional, hedonic, social, and financial), and loyalty among grocerant customers. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 77, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiviharju, A. (2022). Meaningful experiences in South Korean theme cafés [Bachelor’s thesis, University of Applied Sciences]. [Google Scholar]

- Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V., & Hundal, B. S. (2019). Evaluating the service quality of solar product companies using SERVQUAL model. International Journal of Energy Sector Management, 13(3), 670–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumawati, A., & Rahayu, K. S. (2020). The effect of experience quality on customer perceived value and customer satisfaction, and its impact on customer loyalty. The TQM Journal, 32(6), 1525–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, I. K., Lu, D., & Liu, Y. (2020). Experience economy in ethnic cuisine: A case of Chengdu cuisine. British Food Journal, 122(6), 1801–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y., Soltani, E., Li, F., & Ting, C. W. (2024). A cultural theory perspective to service expectations in restaurants and food services. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 16(2), 167–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüthy, B. (2025). Hospitality industry trends for 2025. Available online: https://hospitalityinsights.ehl.edu/hospitality-industry-trends (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Ma, E., Bao, Y., Huang, L., Wang, D., & Kim, M. (2021). When a robot makes your dinner: A comparative analysis of product level and customer experience between the US and Chinese robotic restaurants. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 64, 184–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macawalang, A. H., & Pangemanan, S. S. (2019). Analytical hierarchy process approach on consumer purchase decision in choosing Chinese restaurant in Manado. Journal EMBA: Journal Riset Ekonomi, Management, Bisnis dan Akuntansi, 7(3), 2890–2899. [Google Scholar]

- Madeira, A., Palrão, T., & Mendes, A. S. (2020). The impact of pandemic crisis on the restaurant business. Sustainability, 13(1), 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, M. A. A., Samsudin, A., Noorkhizan, M. H. I., Zaki, M. I. M., & Bakar, A. M. F. A. (2018). Service quality, food quality, image, and customer loyalty: An empirical study at a hotel restaurant. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(10), 1432–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannan, M., Chowdhury, N., Sarker, P., & Amir, R. (2019). Modeling customer satisfaction and revisit intention in Bangladeshi dining restaurants. Journal of Modelling in Management, 14(4), 922–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyanga, W., Makanyeza, C., & Muranda, Z. (2022). The effect of customer experience, customer satisfaction and word of mouth intention on customer loyalty: The moderating role of consumer demographics. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2082015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M. N., & Bartholomew, M. J. (2017). What does it “mean”? A review of interpreting and calculating different types of means and standard deviations. Pharmaceutics, 9(2), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mordor Intelligence. (2023). South Africa foodservice market size & share analysis—Growth trends & forecasts up to 2029. Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/africa-foodservice-market (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Mordor Intelligence. (2025). Hospitality industry in South Africa size & share analysis—Growth trends & forecasts (2025–2030). Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/hospitality-industry-in-south-africa (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- National Restaurant Association. (2024). Economic contributions of the restaurant & foodservice industry. Available online: https://restaurant.org/getmedia/206bb262-fc48-4f00-b91b-3402ea6d97f1/usa_econ_impact_study_fs-3.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Nguyen-Viet, B., & Nguyen, M. P. (2025). Customer incivility’s antecedents and outcomes: A case study of Vietnamese restaurants and hotels. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 8(1), 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyewole, P. (1999). Multi-attribute dimensions of service quality in the fast-food restaurant industry. Journal of Restaurant & Foodservice Marketing, 3(3–4), 65–91. [Google Scholar]

- Pandita, S., Koul, S., & Mishra, H. G. (2021). Acceptance of ride-sharing in India: Empirical evidence from the UTAUT Model. International Journal of Business & Economics, 20(2), 93–117. [Google Scholar]

- Petzer, D., & Mackay, N. (2014). Dining atmospherics and food and service quality as predictors of customer satisfaction at sit-down restaurants. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 3(2), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1998). Welcome to the experience economy. Harvard Business Review Press, 76(4), 97–105. Available online: https://shorturl.bz/qQG (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Prayag, G., Gannon, M. J., Muskat, B., & Taheri, B. (2020). A serious leisure perspective of culinary tourism co-creation: The influence of prior knowledge, physical environment and service quality. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(7), 2453–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, A., & Gahfoor, R. Z. (2020). Satisfaction and revisit intentions at fast food restaurants. Future Business Journal, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratasuk, A., & Charoensukmongkol, P. (2020). Does cultural intelligence promote cross-cultural teams’ knowledge sharing and innovation in the restaurant business? Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, 12(2), 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M. A., & Prayag, G. (2019). Perceived quality and service experience: Mediating effects of positive and negative emotions. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 28(3), 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, T., & Maree, T. (2021). Joy to the (Shopper) World: An S-O-R view of digital place-based media in upmarket shopping malls. Journal of Promotion Management, 27(7), 1031–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K., Kim, H. J., Lee, H., & Kwon, B. (2021). Relative effects of physical environment and employee performance on customers’ emotions, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions in upscale restaurants. Sustainability, 13(17), 9549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saneva, D., & Chortoseva, S. (2018). Service quality in restaurants: Customers’ expectation and customers’ perception. Science and Research Journal, 1(2), 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sashi, C. M., Brynildsen, G., & Bilgihan, A. (2019). Social media, customer engagement and advocacy: An empirical investigation using Twitter data for quick service restaurants. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(3), 1247–1272. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, B. (1999). Experiential marketing. Journal of Marketing Management, 15(1–3), 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. K., Mudgal, S. K., Thakur, K., & Gaur, R. (2020). How to calculate sample size for observational and experimental nursing research studies. National Journal of Physiology, Pharmacy and Pharmacology, 10(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y. H., & Yu, L. (2020). The influence of quality of physical environment, food and service on customer trust, customer satisfaction, and loyalty and moderating effect of gender: An empirical study on foreigners in South Korean Restaurant. International Journal of Advanced Culture Technology, 8(3), 172–185. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, G., Slack, N., Sharma, S., Mudaliar, K., Narayan, S., Kaur, R., & Sharma, K. U. (2021). Antecedents involved in developing fast-food restaurant customer loyalty. The TQM Journal, 33(8), 1753–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, N. J., Singh, G., Ali, J., Lata, R., Mudaliar, K., & Swamy, Y. (2021). Influence of fast-food restaurant service quality and its dimensions on customer perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions. British Food Journal, 123(4), 1324–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souki, G. Q., Antonialli, L. M., Barbosa, A. A. D. S., & Oliveira, A. S. (2020). Impacts of the perceived quality by consumers of à la carte restaurants on their attitudes and behavioural intentions. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 32(2), 301–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyn, N. P., & Labadarios, D. (2011). Street foods and fast foods: How much do South Africans of different ethnic groups consume? Ethnicity and Disease, 21(4), 462–466. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Strong, S. (2023). Taking back taste in food bank Britain: On privilege, failure and (un) learning with auto-corporeal methods. Cultural Geographies, 30(3), 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, D., Helmi Ali, M., Tan, K. H., Sjahroeddin, F., & Kusdibyo, L. (2019). Loyalty toward online food delivery service: The role of e-service quality and food quality. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 22(1), 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sürücü, Ç., & Bekar, A. (2017). The effects of aesthetic value in food and beverage businesses on the aesthetic experiences and revisit intentions of customers. International Journal of Social Science, 1, 373–388. [Google Scholar]

- Taherdoost, H. (2022). What are the different research approaches? Comprehensive review of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method research, their applications, types, and limitations. Journal of Management Science & Engineering Research, 5(1), 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Q. X., Dang, M. V., & Tournois, N. (2020). The role of servicescape and social interaction toward customer service experience in coffee stores. The case of Vietnam. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 14(4), 619–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncer, I., Unusan, C., & Cobanoglu, C. (2021). Service quality, perceived value and customer satisfaction on behavioral intention in restaurants: An integrated structural model. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 22(4), 447–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türker, N., Gökkaya, S., & Acar, A. (2019). Measuring the effect of restaurant servicescapes on customer loyalty. Turizm Akademik Dergisi, 6(2), 255–270. [Google Scholar]

- Uslu, A. (2020). The relationship of service quality dimensions of restaurant enterprises with satisfaction, behavioral intention, eWOM, and the moderator effect of atmosphere. Tourism and Management Studies, 16(3), 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloso, M., & Gomez-Suarez, M. (2023). Customer experience in the hotel industry: A systematic literature review and research agenda. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(8), 3006–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Feng, Y., & Feng, B. (2013, June 23–24). The study on the significance of the difference between demographics and tourist experiences in Macau Casino hotels [Conference session]. International Marketing Science and Information Technology (pp. 198–211), Nanjing, China. [Google Scholar]

- Wibisono, T. D., & Lukito, N. (2020). Factors that influence word-of-mouth behavior in fast food restaurants. In Proceedings of the international conference on management, accounting, and economy (Vol. 151, pp. 197–201). Atlantis Press SARL. Available online: https://www.atlantis-press.com/proceedings/mhehd-22/125975791 (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Wu, J., Chen, J., Yang, T., & Zhao, N. (2024). How to stay competitive: An innovative concept to assess the business competitiveness using online restaurant reviews. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 122, 103836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X., Gursoy, D., & Zhang, M. (2021). Effects of social interaction flow on experiential quality, service quality and satisfaction: Moderating effects of self-service technologies to reduce employee interruptions. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 30(5), 571–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B., & Chan, Y. (2010). A conceptual framework of hotel experience and customer-based brand equity: Some research questions and implications. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 22(2), 174–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S. B., Hlee, S., Lee, J., & Koo, C. (2017). An empirical examination of online restaurant reviews on Yelp.com: A dual coding theory perspective. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(2), 817–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y., & Moon, H. C. (2020). What drives customer satisfaction, loyalty, and happiness in fast-food restaurants in China? Perceived price, service quality, food quality, physical environment quality, and the moderating role of gender. Foods, 9(4), 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zibarzani, M., Abumalloh, R. A., Nilashi, M., Samad, S., Alghamdi, O. A., Nayer, F. K., Ismail, M. Y., Mohd, S., & Akib, N. A. M. (2022). Customer satisfaction with restaurant service quality during the COVID-19 outbreak: A two-stage methodology. Technology in Society, 70, 101977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Constructs | Number of Items | Cronbach’s Alpha Value | X = Mean | σ = Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality Antecedents | ||||

| a. Physical environment | 4 | 0.84 | 5.29 | 0.08 |

| b. Customer service | 4 | 0.85 | 5.24 | 0.09 |

| c. Quality of food | 5 | 0.86 | 5.48 | 0.08 |

| Experience dimensions | ||||

| d. Aesthetic experience | 3 | 0.84 | 5.33 | 0.07 |

| e. Escapist experience | 3 | 0.94 | 4.86 | 0.10 |

| f. Entertainment experience | 3 | 0.94 | 4.53 | 0.08 |

| g. Educational experience | 3 | 0.97 | 4.28 | 0.11 |

| Customer satisfaction | 3 | 0.95 | 5.31 | 0.08 |

| Revisit intentions | 3 | 0.96 | 5.55 | 0.08 |

| Constructs | Factor Loadings | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical environment | 0.873 | 0.699 | |

| The restaurant’s overall appearance is appealing. | 0.88 | ||

| This restaurant is beautifully decorated. | 0.91 | ||

| The restaurant has a pleasant atmosphere. | 0.71 | ||

| Employees are neatly dressed. | 0.54 | ||

| Customer service | 0.850 | 0.596 | |

| The restaurant serves food exactly as ordered. | 0.66 | ||

| The restaurant provides quick service. | 0.73 | ||

| The restaurant staff provides information when needed. | 0.78 | ||

| The restaurant seems to have the customer’s best interests at heart. | 0.88 | ||

| Quality of food | 0.857 | 0.516 | |

| The meal tasted pleasant. | 0.77 | ||

| The meal was freshly served. | 0.70 | ||

| The meal presentation was visually attractive. | 0.70 | ||

| The meal was served at the right temperature. | 0.67 | ||

| The menu offers a variety of interesting meals. | 0.72 | ||

| The restaurant serves healthy meal choices. | 0.69 | ||

| Aesthetic experience | 0.832 | 0.647 | |

| Overall, the visual experience at the restaurant was attractive. | 0.71 | ||

| Overall, the tasting experience at the restaurant was good. | 0.86 | ||

| Overall, the experience of the meal presentations was attractive. | 0.79 | ||

| Escapist experience | 0.944 | 0.850 | |

| The experience at the restaurant allowed me to forget my daily routine. | 0.91 | ||

| The experience at the restaurant allowed me to relax by getting away from some stress. | 0.96 | ||

| The experience at the restaurant allowed me to have a break from my routine. | 0.90 | ||

| Entertainment experience | 0.944 | 0.854 | |

| The experience at the restaurant was fun. | 0.94 | ||

| The experience at the restaurant was enjoyable. | 0.96 | ||

| The experience at the restaurant was entertaining. | 0.87 | ||

| Educational experience | 0.966 | 0.896 | |

| I learned a lot from my experience at the restaurant. | 0.95 | ||

| The experience at the restaurant stimulated my curiosity to learn new things. | 0.95 | ||

| The experience at the restaurant was a real learning experience. | 0.96 | ||

| Customer satisfaction | 0.944 | 0.852 | |

| This restaurant exceeded my expectations. | 0.91 | ||

| I am pleased with my visit to this restaurant. | 0.93 | ||

| Overall, I am satisfied with my experience at this restaurant. | 0.92 | ||

| Revisit intentions | 0.954 | 0.876 | |

| I would visit this restaurant again in the near future. | 0.93 | ||

| I would recommend this restaurant to my friends/relatives. | 0.96 | ||

| This is the kind of restaurant I’d praise online. | 0.91 |

| Hypotheses | Standardised Beta | p-Value | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: There is a significant positive relationship between the quality of the physical environment and | Partially supported | ||

| H1.1: aesthetic experience | 0.197 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H1.2: escapist experience | 0.072 | 0.156 | Not supported |

| H1.3: entertainment experience | 0.085 | 0.102 | Not supported |

| H1.4: educational experience | 0.047 | 0.377 | Not supported |

| H2: There is a significant positive relationship between customer service and | Supported | ||

| H2.1: aesthetic experience | 0.227 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2.2: escapist experience | 0.286 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2.3: entertainment experience | 0.380 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2.4: educational experience | 0.369 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3: There is a significant positive relationship between the quality of food and | Supported | ||

| H3.1: aesthetic experience | 0.614 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3.2: escapist experience | 0.490 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3.3: entertainment | 0.363 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3.4: educational experience | 0.314 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H4: There is a significant positive relationship between | Partially supported | ||

| H4.1: aesthetic experience and customer satisfaction | 0.653 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H4.2: escapist experience and customer satisfaction | 0.106 | 0.062 | Not supported |

| H4.3: entertainment experience and customer satisfaction | 0.137 | 0.015 | Supported |

| H4.4: educational experience and customer satisfaction | 0.070 | 0.165 | Not supported |

| H5: There is a significant positive relationship between customer satisfaction and positive revisit intention. | 0.914 | 0.000 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sithole, M.V.; Roux, T.; Retief, M. Experiential Marketing Through Service Quality Antecedents: Customer Experience as a Driver of Satisfaction and Revisit Intentions in South African Restaurants. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050227

Sithole MV, Roux T, Retief M. Experiential Marketing Through Service Quality Antecedents: Customer Experience as a Driver of Satisfaction and Revisit Intentions in South African Restaurants. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(5):227. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050227

Chicago/Turabian StyleSithole, Moses Vuyo, Therese Roux, and Miri Retief. 2025. "Experiential Marketing Through Service Quality Antecedents: Customer Experience as a Driver of Satisfaction and Revisit Intentions in South African Restaurants" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 5: 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050227

APA StyleSithole, M. V., Roux, T., & Retief, M. (2025). Experiential Marketing Through Service Quality Antecedents: Customer Experience as a Driver of Satisfaction and Revisit Intentions in South African Restaurants. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(5), 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050227