Abstract

Tourism planning in port cities faces the dual challenge of maximizing economic benefits while mitigating environmental and social pressures. This study examines the case of Piraeus, Greece, by integrating insights from both visitors and residents to explore how stakeholder perceptions can inform sustainable and resilient destination planning. Drawing on primary data collected through large-scale surveys of visitors and local residents, the analysis applies a multidimensional framework to assess economic, environmental, and social impacts of tourism. Findings reveal strong visitor spending and cultural engagement alongside concerns about infrastructure, pollution, and service quality. Residents acknowledge job creation and business activity but emphasize rising living costs, overcrowding, and limited inclusion in tourism governance. By bridging these perspectives, this study highlights the importance of multiple-stakeholder analysis for integrated tourism planning and proposes governance strategies to enhance sustainability and resilience in port destinations such as Piraeus.

1. Introduction

Tourism in port cities emerged as a critical sector that contributed to local economies worldwide, intertwining the maritime industry with regional development. These destinations often attract a diverse spectrum of travelers, ranging from cruise passengers to business tourists, effectively transforming them into gateways that facilitate cultural exchange and economic interaction (Galani, 2025). However, the boom in traffic tourism has significant challenges, particularly in maintaining sustainability in these regions. The unique challenges faced by port cities are in the act of balance between accommodating increasing tourist flows and mitigating the environmental impact arising from such activities (Konstantinos et al., 2023). Piraeus, Greece’s main port, deals with these challenges and serves as a crucial case study to examine effective strategies that harmonize the development of tourism with sustainable practices.

The development of sustainable tourism in port cities such as Piraeus requires the integration of multiple perspectives from stakeholders, including government entities, local companies, environmental organizations and communities that reside within these urban landscapes (Cocuzza et al., 2025). The inclusion of several voices is essential for the elaboration of innovative solutions that address the economic benefits of tourism and its environmental branches (Georgousi, 2022). For example, the development of bicycle sharing systems showed potential as an effective strategy for promoting sustainable tourism and at the same time improving coastal and maritime experiences for visitors (Bakogiannis et al., 2018). This holistic approach to stakeholder involvement facilitates awareness and response ability to improve local environmental concerns, particularly regarding the management of the pressures associated with transient tourist populations (Paraskevopoulou et al., 2019).

In addition, the intricacies of the impact of traffic tourism on urban infrastructure raise critical questions about resource allocation and urban planning. In light of the growing emphasis on sustainability, Piraeus’ administration has started several EU-funded projects intended to address energy use and reduce emissions within the port area (Platias & Spyrou, 2023). Such initiatives align with a broader movement towards sustainable urban resource distribution, promoting the efficient movement of goods while decreasing the environmental footprint (Anagnostopoulou & Poulou, 2017). To evaluate the implications of these initiatives in the context of Piraeus is to highlight the vital synergy between traffic tourism and the sustainability objectives in the contemporary governance of the city.

When exploring this case, it is increasingly clear that the city must effectively navigate the delicate balance between promoting a vibrant tourism sector and ensuring sustainable practices that benefit local residents and visitors (Savoldi, 2025). In critically evaluating current strategies in force and identifying areas of improvement, this research aims to contribute to the broader discourse around port cities and sustainable development. The result will potentially establish fundamental insights that can be applicable to other port cities that face similar challenges in the harmonization of traffic tourism with sustainability, emphasizing the meaning of the collaboration of stakeholders in the approach of these pressing issues (Anastasopoulos et al., 2024).

2. Literature Review

Port cities, defined as urban centers located along coasts and typically characterized by their functioning ports, play a fundamental role in the ecosystems of global tourism. These cities serve as critical knots for international trade, simultaneously attracting millions of tourists every year, thus guiding both economic growth and cultural exchanges (Santos et al., 2019). The integration of logistics, trade, and tourism within these metropolitan areas underlines their meaning, particularly in the context of globalized mobility and the increase in maritime traffic. In particular, they are unique in hosting complex interrelationships between urban environments and maritime activities, which require strategic planning to improve their competitiveness and appeal as destinations.

Destination planning in urban maritime environments emerges as a multidimensional effort that requires a weighted evaluation of sustainability and resilience. The pressures exerted by a rapidly evolving climate, together with the transition to more environmental travel behaviors among tourists, position sustainability as a fundamental principle in the development agendas of port cities (Cocuzza et al., 2025). The effective planning of destinations can lead to better management of tourist flows and an optimized visitor experience, simultaneously safeguarding the environmental integrity of these areas. Resilience is also a crucial aspect, since port cities must adapt to numerous challenges such as the increase in sea level, infrastructure vulnerability, and floating tourist needs, thus guaranteeing their feasibility as long-term tourist destinations (Traskevich & Fontanari, 2023).

Involvement with main stakeholders is fundamental in reaching complete and effective destination planning. In port cities, the main stakeholders generally include local governments, private companies, and community members. Each group of stakeholders has distinct perspectives and motivations that influence planning processes and results. Local governments often give priority to economic growth and the creation of jobs, while companies focus on profitability and operational efficiency. In the meantime, community members can emphasize cultural conservation, quality of life, and environmental concerns (Farmaki, 2020; Panse et al., 2021). The intrinsic conflicts deriving from these different objectives highlight the need for governance mechanisms that recognize and mediate different interests to encourage synergies in development activities.

The complexities addressed by port cities extend beyond the dynamics of the stakeholders to include significant environmental challenges and the need to harmonize tourism with local economies. Port cities often face balancing the inflow of tourists and minimizing the ecological imprint of related activities (Santos et al., 2019). Questions such as pollution, habitat degradation, and infrastructure tension require strategic planning that introduces innovative solutions to integrate tourism and urban life in a sustainable way. This includes the adoption of ecological policies, the improvement of public infrastructures, and the distribution of technologies that mitigate environmental impacts while maintaining the attraction of urban maritime locations (Cocuzza et al., 2025).

The commitment of stakeholders and collaborative approaches are fundamental for the formulation of governance mechanisms that effectively face these multifaceted challenges. By incorporating different points of view and promoting partnerships between stakeholders, port cities can develop inclusive strategies that enhance the destination’s appeal. Effective governance structures, characterized by transparency, participation of the interested parties, and shared responsibilities, emerge as instrumental to navigate the complexities associated with tourism in these unique urban environments. Collaborative destination planning not only encapsulates the vision of the development of sustainable tourism but also lays the foundations for resilient urban ecosystems in port cities. The continuation of sustainability and resilience in urban maritime environments is increasingly critical due to the unique challenges posed by tourist activities and the pressures exerted on local ecosystems. Port cities, serving as vital nodes in world trade and tourism, have adopted various principles of sustainability to mitigate the negative impacts on their urban ecosystems (Ettorre et al., 2023). The alignment of tourism development with wider environmental, economic, and social objectives promotes practices that preserve cultural heritage and natural resources while improving community well-being. Key practices often include the implementation of strict regulations concerning waste management, the promotion of ecological infrastructure, and the promotion of local businesses to encourage a circular economy, thus facilitating a more sustainable tourist model.

In addition, the concept of resilience appears to be an essential component of strategic planning in port cities, particularly in the face of climate change and world crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Traskevich & Fontanari, 2023; Zhang et al., 2024). Resilience in this context refers to the capacity of a city to absorb disturbances, to adapt to modified circumstances, and to develop new strategies to thrive in a rapidly evolving environment. The tourism sector in port cities is particularly vulnerable to these crises. Consequently, measures to strengthen resilience are necessary to maintain operational capacity and support sustainable economic growth. Adaptability can be favored thanks to strategies such as diversified tourism offers, investments in sufficiently robust infrastructure to withstand climate impacts, and reactive governance structures which can rotate according to emerging challenges.

In the advancement of sustainable governance within port systems, the role of stakeholder participation cannot be overestimated. Engaging various groups of stakeholders—ranging from communities and local businesses to government entities and NGOs—intends for a multitude of prospects and interests to shed light on decision-making processes (Leon et al., 2022; Jarratt & Davies, 2020). Inclusive governance models facilitate collaboration, promote public confidence, and improve the legitimacy of sustainability initiatives. Effective participation mechanisms can take various forms, such as public consultations, participatory planning sessions, and stakeholder forums, ultimately contributing to more efficient and equitable governance.

Technological innovations and adaptive strategies are essential to promote resilience and sustainability in the tourism sector and in the broader community context. The integration of intelligent technologies, including the analysis of data and solutions of the Internet of Things (IoT), can optimize the use of resources, improve the experiences of visitors, and rationalize operations in port cities (Abdelmalak, 2024; Della Corte et al., 2021). Such innovations can facilitate real-time monitoring of environmental conditions, allowing rapid responses to unfavorable situations, whether they come from factors of environmental stress or tourism influx. In addition, promoting an innovation culture in the tourism sector can encourage the development of new strategies that deal with the complex dynamics of urban maritime environments.

Illustrating these concepts, several case studies on port cities illustrate sustainable practices and successful resilience frameworks. For example, the integration of green architecture and public transport systems in Barcelona has considerably reduced carbon emissions while improving connectivity in the urban environment (Andrade et al., 2021). Likewise, the implementation of adaptive management practices in Venice has enabled the city to better respond to tourist pressures and challenges related to climate, suggesting a potential path for other port cities struggling with similar problems (Bui et al., 2020). These examples highlight the importance of tailor-made and place-based strategies that meet local contexts and the needs of stakeholders, promoting a global approach to sustainable and resilient urban maritime environments. Governance in port cities requires a sophisticated approach which approaches the complexities inherent in the coordination of the interests of stakeholders, particularly in the field of tourism. The interaction between public authorities, local companies, and groups of citizens often leads to challenges with multiple facets which require effective negotiation and compromise (D. Nguyen et al., 2016). These stakeholders often have contradictory priorities. While public authorities can prioritize long-term sustainability and resilience, local businesses can focus on immediate economic gains, potentially compromising wider environmental objectives. This divergence requires a framework of governance which allows collaborative decision-making, promoting an integrated vision of the development of tourism which can harmonize these varied interests.

In terms of policy, the landscape is still complicated by national regulations which may not be aligned fully with local needs or capacities. Stakeholders often express frustration in the face of the disjunction between national tourism policies and realities on the ground in port cities. Indeed, Chan et al. (2020) and Fabry and Zeghni (2019) underline that such disparities can hinder the effective implementation of sustainable tourist initiatives, leading to a disconnection between political intention and local practice. For example, a national emphasis on promoting tourism growth can ignore local environmental impacts or cultural preservation, leading to the opposition of stakeholders and community fatigue. Consequently, understanding and fighting against these contradictory interests is essential to obtain sustainable development in urban maritime environments.

In response to these governance challenges, the adoption of adaptive management frameworks has been identified as essential to promote resilience in tourism in the port city (Amore et al., 2018; Sandhu et al., 2019). These executives recommend continuous feedback mechanisms which integrate the perspectives of stakeholders on several levels, ensuring that tourism strategies remain flexible and sensitive to the evolution of environmental conditions and the needs of the community. This iterative approach makes it possible to identify the best practices and refinement of strategies over time, ultimately improving the capacity of port cities to adapt to unforeseen challenges such as climate change or economic slowdowns.

The evaluation of the efficiency of existing governance structures reveals important gaps in the promotion of sustainable tourism strategies adapted to the unique challenges posed by port environments (Anastasopoulos et al., 2024). Many port cities use traditional governance models that inadequately treat dynamic interactions of stakeholders influenced by world tourism trends. Consequently, these structures may lack the agility necessary to respond to the evolution of the complexities of urban maritime tourism, thus undergoing sustainable development efforts. It becomes essential to critically assess these governance frameworks to discover potential areas for improvement, particularly their ability to integrate various voices of stakeholders in decision-making processes.

Future governance models must focus on promoting collaboration between sectors and scales, addressing the unique complexities of tourism in port cities to promote operational resilience and sustainability (Cocuzza et al., 2025; Ettorre et al., 2023). This implies strengthening not only partnerships between government agencies, businesses, and community organizations but also technology to improve communication and commitment strategies. By prioritizing transparent and inclusive governance mechanisms, port cities can create a more coherent approach to tourism that balances economic imperatives with environmental management and community well-being. These executives will be crucial to help these cities navigate in the complex and often competing requirements of several stakeholders, finally positioning them to flourish in the middle of rapid change and uncertainty.

Beyond tourism-specific studies, research on smart and sustainable cities provides additional insights into how urban destinations can balance economic development with environmental quality and social well-being. Shmelev et al. (2018) conducted a comparative sustainability analysis of Taipei and Almaty, applying a multidimensional framework that integrated economic, social, and environmental indicators. Their findings demonstrated that economic growth can be decoupled from environmental degradation when governance frameworks prioritize sustainability-oriented innovations. This perspective is highly relevant for port cities such as Piraeus, which must simultaneously address tourism competitiveness, urban development, and ecological integrity.

A complementary strand of research emphasizes the role of ecosystem services as a foundation for tourism sustainability. Shmelev et al. (2023) propose a multidimensional, non-monetary framework to map nature’s contributions to people, highlighting how provisioning, regulating, and cultural services are distributed across landscapes. Their findings underscore that environmental quality is not only an aesthetic factor for visitors but also a critical ecosystem service that sustains both social well-being and economic vitality. In the context of port destinations, recognizing these interdependencies is essential for developing governance strategies that ensure tourism development does not undermine the very environmental assets upon which it depends.

Taken together, these contributions expand the conceptual foundation of this study by situating visitor and resident perceptions within broader discourses on urban sustainability and ecosystem services. Integrating these perspectives strengthens the theoretical framing of the present research and aligns it with emerging debates on the role of cities as complex socio-ecological systems. This broader perspective underlines why the present study compares visitors’ and residents’ perceptions of sustainability in Piraeus, as these reflect key stakeholder voices within wider socio-ecological dynamics.

3. Framework and Hypotheses

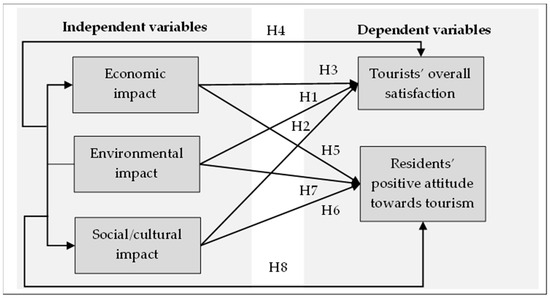

This study is underpinned by two complementary theoretical perspectives. First, sustainability theory stresses the integration of environmental, social, and economic pillars to ensure the long-term viability of tourism destinations (Butler, 1999). In the case of Piraeus, this perspective highlights the importance of balancing visitor satisfaction with residents’ quality of life and environmental stewardship. Second, stakeholder theory emphasizes that effective governance in tourism requires addressing the diverse, and sometimes conflicting, interests of multiple actors, including visitors, residents, businesses, and policymakers (Byrd, 2007). In port cities such as Piraeus, these tensions are particularly evident, as tourism development intersects with trade, cultural heritage, and urban quality of life. Taken together, these theories provide the conceptual foundation for the present study and inform the framework shown in Figure 1, which positions sustainability dimensions as antecedents of both visitor satisfaction and residents’ attitudes towards tourism.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model used in this study.

Building on these theoretical perspectives, the literature review on sustainable tourism and destination governance highlights the necessity of considering the three classical pillars of sustainability (economic, social, and environmental) in an integrated way. Previous research has shown that visitors mainly evaluate destinations on the basis of experiential and environmental quality (Paraskevopoulou et al., 2019; Konstantinos et al., 2023), while residents tend to balance perceived economic benefits with social and environmental consequences (Farmaki, 2020; Fabry & Zeghni, 2019; Savoldi, 2025). These perspectives converge on the recognition that tourism sustainability depends on aligning short-term visitor satisfaction with long-term community well-being, supported by inclusive governance (Cocuzza et al., 2025; Traskevich & Fontanari, 2023).

Based on this review, a theoretical model is proposed in which the three sustainability dimensions (economic, social, and environmental) are examined in how they influence visitors and residents differently. For visitors, it examines how they relate to overall service satisfaction, while for residents, it examines attitudes toward tourism and support for tourism development. The model therefore assumes that sustainability perceptions form the antecedents of satisfaction and support, with governance considerations acting as contextual factors.

The perceptions of visitors of the environment considerably influence their overall satisfaction in tourist contexts. Key factors such as clean installations, natural beauty, and sustainability practices contribute prominently to this perception. For example, Abbasi et al. (2023) have shown that urban tourist attractions with high environmental quality lead to increased tourist satisfaction. Likewise, T. N. Nguyen and Huynh (2024) found that a well-maintained environment improves the enjoyment of visitors in tourist sites. In addition, Govindarajo and Khen (2020) highlighted the importance of the quality of service, which mixes with environmental aesthetics, to shape loyalty to a destination. Jarvis et al. (2016) also underlined the multidimensional relationship between environmental factors and travel satisfaction. Finally, Breiby and Slåtten (2018) noted that aesthetic experiential qualities promote loyalty, stressing the essential role of the quality of the environment in the satisfaction of tourism. Based on the literature, hypothesis H1 was developed:

H1.

Visitors’ satisfaction is positively influenced by their perceptions of environmental quality.

Social and cultural interactions play a crucial role in modeling the satisfaction of visitors in various contexts. Interactive technologies, for example, improve social experiences, allowing visitors to engage more significantly with cultural contexts (Ponsignon & Derbaix, 2020). In addition, the interpretation of heritage significantly influences the learning experience and therefore affects tourist satisfaction, highlighting the need for effective communication of cultural values (Moreno-Melgarejo et al., 2019). For example, in cultural tourism in China, the strategies that provide authentic experiences are fundamental to improve the satisfaction of visitors (Jing & Loang, 2024). In addition, the emotional dimensions of satisfaction in cultural events underline the importance of social and cultural commitment to improve the overall experiences of visitors (Christou et al., 2018). Finally, the satisfaction of visitors mediates the relationship between memorable tourist experiences and behavioral intentions, further illustrating the impact of social factors in heritage tourism (Rasoolimanesh et al., 2022). Based on the literature, hypothesis H2 was developed:

H2.

Visitors’ satisfaction is positively influenced by their perceptions of social and cultural interactions.

The perceptions of the economic benefits of visitors play a crucial role in improving their overall satisfaction. Economic benefits, such as increasing spending during travel and the positive impact of the community, contribute significantly to this perception. Jarvis et al. (2016) point out that understanding the interaction of economic, social, and environmental factors shapes the satisfaction of the trip and influences the return of visitors’ intentions. In addition, the value co-creation between residents and tourists positively affects satisfaction levels, as reported by Lin et al. (2017). The satisfaction derived from the impacts of perceived tourism is explored even more in Alrwajfah et al. (2019), reflecting how community involvement promotes positive perceptions. In addition, Gnanapala (2015) emphasizes that tourists’ perceptions correlate directly with their satisfaction classifications, reinforcing the importance of the economic benefits perceived in destination management. Based on the literature, hypothesis H3 was developed:

H3.

Visitors’ satisfaction is positively influenced by their perceptions of economic benefits.

The satisfaction of visitors is significantly influenced by environmental and social perceptions, often exceeding economic factors. For example, the research indicates that visitors to Eravikulam National Park in India have shown higher levels of satisfaction when environmental conservation was priority, demonstrating the importance of ecological considerations in tourism (Velmurugan et al., 2021). In the same way, a study on residents in the Petra region, Jordan, revealed that positive perceptions about the development of tourism have favored greater satisfaction for the local administration, highlighting the role of social acceptance (Alrwajfah et al., 2019). While the economic benefits are essential, Jarvis et al. (2016) discovered that social and environmental satisfaction was strongly related to return visits. In addition, Sanchez del Rio-Vazquez et al. (2019) have underlined that the environmental and social impacts significantly influence overall satisfaction levels, suggesting that these perceptions can be more fundamental than economic factors in the guidance of visitors’ experiences. Based on the literature, hypothesis H4 was developed:

H4.

The influence of environmental and social perceptions on visitors’ satisfaction will be stronger than that of economic perceptions.

The perceptions of residents on economic benefits significantly influence their support for tourism, which influence factors such as the creation of jobs, local investments, and the development of the community. A positive view of the place and perceived tourist impacts can improve the support of residents for tourist initiatives (Stylidis et al., 2014). The creation of jobs is often cited as a key advantage, in which greater job opportunity leads to greater local investment and involvement in community projects, promoting a sense of shared prosperity (Gursoy et al., 2019). Communities perceive the impact of tourism on the quality of life as critical, with rural areas particularly valuing tourism for its economic contributions (Yu et al., 2018). In addition, understanding the relationships between the perceptions of residents and the benefits related to tourism is crucial to obtain support for the development of ongoing tourism (Kodaş et al., 2022). Based on the literature, hypothesis H5 was developed:

H5.

Residents’ support for tourism is positively influenced by their perceptions of economic benefits.

The perceptions of residents about the social and cultural benefits of tourism significantly influence their support for the development of tourism within their communities. Positive perceptions, such as the increase in cultural exchange and community cohesion, lead to greater support from residents (Kodaş et al., 2022). Stylidis et al. (2014) argue that the view of the place by the residents is intertwined with these perceptions, affecting their attitudes towards tourist impacts. On the contrary, negative perceptions can cause resistance and opposition to tourist initiatives (Li et al., 2019). It is crucial that political leaders recognize these dynamics and promote a shared understanding of the possible benefits of tourism. By improving local participation in tourism planning, communities can reinforce development support, which ultimately leads to sustainable tourism practices that are aligned with the social and cultural aspirations of residents (Kodaş et al., 2022; Stylidis et al., 2014). Based on the literature, hypothesis H6 was developed:

H6.

Residents’ support for tourism is positively influenced by their perceptions of social and cultural benefits.

The perceptions of residents on environmental costs significantly influence their support for tourism, creating a complex dynamic between economic benefits and ecological sustainability. Li et al. (2019) show that as residents become more aware of the environmental impacts associated with tourism, their support can decrease despite the potential economic earnings. This feeling is further echoed in Gursoy et al. (2019), who discovered that negative perceptions about the environmental impact of tourism can alter the attitudes of the community towards development. Likewise, Charag et al. (2021) illustrate how residents in Kashmir express concerns about ecological degradation, reflecting a clash between economic aspirations and environmental management. Jeon et al. (2016) underline the importance of the quality of perceived life, suggesting that communities give priority to ecological sustainability when they respond to the development of tourism, thus modeling a critical balance between economic growth and environmental conservation. Based on the literature, hypothesis H7 was developed:

H7.

Residents’ support for tourism is negatively influenced by their perceptions of environmental costs.

The interaction between the economic and social advantages of tourism and environmental concerns is crucial to shape the perspectives of the community. Kodaş et al. (2022) have found that residents often weigh the economic incentives for tourism against environmental degradation, leading to increased tourism support despite the ecological implications. Liasidou et al. (2021) stressed that in rural areas, the perceived benefits can eclipse more environmental damage, because communities are experiencing social cohesion and improved economic opportunities. Çelik and Rasoolimanesh (2023) argue that residents’ cost-dispatch attitudes considerably influence tourism support, often prioritizing immediate economic gains. In addition, Song et al. (2021) says that understanding the perspectives of stakeholders is essential to promote sustainable tourism, which suggests that promoting community support requires responding both to environmental advantages and concerns. Based on the literature, hypothesis H8 was developed:

H8.

The influence of economic and social benefits will outweigh environmental concerns in shaping residents’ support for tourism.

This framework positions the three sustainability pillars as central explanatory factors for visitor satisfaction and resident support. It further allows for a comparative analysis of the two groups, thereby offering insights into the synergies and tensions that underpin sustainable destination planning in Piraeus. Figure 1 presents this research’s theoretical model (framework).

4. Methodology

This study is part of the research project TOUKBASEED (Tourism Knowledge Base for Socio-Economic and Environmental Data Analysis), which aimed to develop a comprehensive framework for analyzing sustainability perceptions in tourism destinations. Within this project, a quantitative, survey-based research design was employed to investigate the perceptions of two key stakeholder groups in Piraeus, visitors and local residents. The population for the visitor survey comprised cruise and ship-line passengers disembarking at the Port of Piraeus during the research period (July–October 2024). The resident survey targeted adult inhabitants of Piraeus, selected from diverse neighborhoods to capture a broad range of perspectives. The dual-sample approach was selected to provide a comprehensive perspective on tourism sustainability, capturing both the demand side (visitors’ satisfaction) and the community side (residents’ attitude towards tourism). The design of this study followed previous research that emphasizes the importance of integrating multiple stakeholder voices into destination planning (Pinhal et al., 2025; Sigala, 2021).

In line with this design, data collection was carried out through two structured questionnaires that were tailored to each stakeholder group. In total, 280 valid responses were collected from visitors and 216 from residents. A survey questionnaire was selected as the primary research tool because it enables the systematic collection of standardized responses from a relatively large number of participants, ensuring comparability between visitor and resident groups. This method is widely used in tourism perception and governance studies, as it allows for the quantification of attitudes and the testing of hypothesized relationships between sustainability dimensions and satisfaction (e.g., Stylidis et al., 2014; Gursoy et al., 2019). In the present study, questionnaires provided an efficient and reliable means of capturing both visitors’ and residents’ perceptions within the limited timeframe of fieldwork, while maintaining consistency across the two stakeholder groups. The sample sizes are consistent with earlier tourism perception studies (e.g., Stylidis et al., 2014; Andereck et al., 2005). Both surveys employed a non-probability convenience sampling method, which is widely used in tourism studies given the practical challenges of obtaining random samples of transient populations such as cruise visitors. Participation was voluntary, anonymity was guaranteed, and respondents were informed of the purpose of the study before completing the questionnaire.

The questionnaires were structured around three main sections. The first section assessed respondents’ perceptions of the sustainability dimensions of tourism, covering economic, social, and environmental aspects. For visitors, items focused on service satisfaction, environmental quality, social interactions, and perceived economic contributions of tourism. For residents, items focused on perceived economic benefits such as job creation and business support, social–cultural benefits such as improvements in quality of life and community pride, and environmental impacts such as pollution and congestion. The second section measured overall evaluation variables, including visitors’ overall service satisfaction, value-for-money, and behavioral intentions (e.g., revisit or recommend), as well as residents’ general attitudes toward tourism and support for tourism development. The final section included demographic and control variables, such as gender, age, education, and employment status for residents, as well as travel characteristics and visit frequency for tourists. All perceptual items were measured on five-point Likert scales ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5) or from “very dissatisfied” (1) to “very satisfied” (5).

Data analysis was conducted in several stages. First, descriptive statistics were used to profile both visitor and resident samples. Second, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) combined with Cronbach’s alpha reliability tests was applied to validate the internal consistency of grouped items reflecting sustainability-related constructs. For the visitor dataset, this process confirmed three main constructs: service satisfaction, environmental perceptions, and social perceptions, while economic items such as value-for-money were treated as standalone variables. For the resident dataset, two factors emerged, social–environmental perceptions and attitudes toward tourism, complemented by standalone economic items. Third, correlation analysis (Spearman’s rank correlation) was performed to examine associations between sustainability perceptions and outcome variables, namely service satisfaction for visitors and support for tourism for residents. Finally, multiple regression analyses were used to test research hypotheses by estimating the predictive effects of economic, social, and environmental perceptions on overall satisfaction and support. All statistical procedures were conducted using SPSS 23, with significance levels set at p < 0.05 (Field, 2009; Hair et al., 2020).

5. Results

5.1. Visitors (Return-to-Port Τourists)

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted on the visitor dataset (N = 280) to identify the main structure of sustainability-related perceptions (Table 1). The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure confirmed sampling adequacy (KMO = 0.911), and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (x2 = 1604.21, p < 0.001), indicating suitability of the data for factor analysis. The analysis generated three main constructs: perceived environmental impact, perceived social impact, and tourist overall satisfaction, while the economic aspect value-for-money (perceived economic impact) was treated as a standalone indicator due to lower internal consistency when combined with other items. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients confirmed reliability for the grouped constructs, exceeding the commonly accepted threshold of 0.70.

Table 1.

Exploratory factor analysis results/variables used (visitors).

Correlation analysis revealed that visitors’ overall satisfaction was strongly and positively correlated with both perceived environmental impact (ρ = 0.52, p < 0.01) and perceived social impact (ρ = 0.47, p < 0.01) (Table 2). Perceived economic impact also correlated significantly with satisfaction, but at a weaker magnitude (ρ = 0.28, p < 0.05). This suggests that visitors’ satisfaction is shaped predominantly by experiential and sustainability-related factors, while economic considerations play a secondary role.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix (visitors).

To provide a clearer illustration of these relationships, Figure 2 presents a bubble chart of the correlations. The visualization highlights the comparatively stronger effects of environmental and social perceptions relative to economic ones, while also revealing the interconnections among sustainability dimensions.

Figure 2.

Bubble chart of correlations among visitor satisfaction and sustainability dimensions. Note: Bubble size is proportional to the correlation coefficient (Spearman’s ρ). All correlations are positive; larger bubbles indicate stronger associations.

Regression analysis provided further support for these relationships (Table 3). The model explained a substantial proportion of variance in satisfaction (adjusted R2 = 0.307, F = 23.41, p < 0.001). Among the predictors, environmental perceptions emerged as the strongest determinant (β = 0.34, p < 0.01), followed by social perceptions (β = 0.28, p < 0.05). Economic evaluations (value-for-money) contributed marginally (β = 0.17, p < 0.10), suggesting that although price considerations influence satisfaction, they are less decisive than environmental quality and social–cultural experiences.

Table 3.

Regression results predicting visitors’ overall satisfaction (visitors).

To further clarify the contribution of each factor, partial R2 values were calculated. Perceived environmental impact accounted for approximately 25% of the explained variance in satisfaction, while perceived economic impact added about 5%, and perceived social impact contributed a further 3%. Residual diagnostics supported the adequacy of the model: residuals were approximately normally distributed, no significant heteroskedasticity was detected, and collinearity diagnostics showed acceptable tolerance and VIF values (all VIF < 1.8). The Durbin–Watson statistic (2.316) indicated no autocorrelation issues. Taken together, these results provide confidence in the robustness of the regression estimates.

The results confirm hypotheses H1 and H2, which proposed positive effects of perceived environmental and social impact on visitors’ overall satisfaction. Hypothesis H3, regarding economic perceptions, was only partially supported, as economic aspects had a weaker influence. Finally, the relative strength of predictors confirmed hypothesis H4, which anticipated that perceived environmental and social perceptions would outweigh economic perceptions in shaping satisfaction. These findings align with prior research emphasizing the role of environmental quality and cultural engagement in cruise tourism satisfaction (Paraskevopoulou et al., 2019; Breiby & Slåtten, 2018). They also reinforce the argument that sustainability-related dimensions form a cornerstone of competitiveness in port destinations, as visitors are increasingly sensitive to service quality, environmental cleanliness, and authentic cultural encounters.

5.2. Residents

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted on the resident dataset (N = 216) to examine perceptions of tourism’s sustainability impacts (Table 4). The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was high (KMO = 0.851), and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (x2 = 497.13, p < 0.001), indicating the suitability of the data for factor analysis. Two constructs were identified: perceived social–environmental impact and positive attitude toward tourism. The first describes residents’ views on cultural heritage, quality of life, and environmental management, while the second reflects more general positive attitudes toward the presence of tourism in Piraeus. Cronbach’s alpha values were acceptable (α = 0.80 for first; α = 0.65 for second), while positive impact on local businesses was retained as standalone indicator.

Table 4.

Exploratory factor analysis results/variables used (residents).

Correlation analysis revealed strong and significant associations among all three constructs (Table 5). Residents’ positive attitudes toward tourism were positively correlated with both their perceptions of social–environmental impacts (ρ = 0.45, p < 0.01) and their perceptions of economic impacts (ρ = 0.50, p < 0.01). Likewise, perceived social–environmental impacts were strongly correlated with perceived economic impacts (ρ = 0.53, p < 0.01). These results indicate that residents who view tourism as beneficial from an economic standpoint also tend to acknowledge its social–environmental contributions and that these dimensions are closely interlinked in shaping overall attitudes toward tourism in Piraeus.

Table 5.

Correlation matrix (residents).

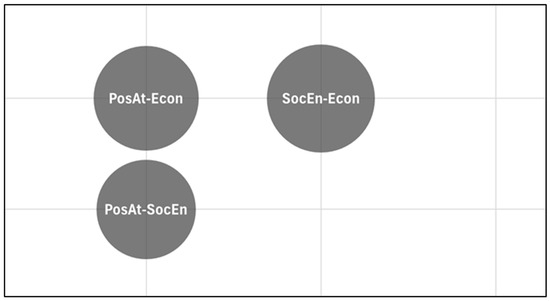

Figure 3 provides a bubble chart representation of these correlations, where bubble size reflects the magnitude of association. The visual emphasizes the relatively balanced and mutually reinforcing relationships across the three dimensions, reinforcing the interpretation of residents’ perceptions as an interconnected system of sustainability-related factors.

Figure 3.

Bubble chart of correlations among residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts. Note: Bubble size is proportional to the correlation coefficient (Spearman’s ρ). All correlations are positive; larger bubbles indicate stronger associations.

Regression analysis confirmed that both perceived social–environmental impact and perceived economic impact significantly predict residents’ positive attitudes toward tourism (Table 6). The model was statistically robust, explaining 31.3% of the variance in attitudes (adjusted R2 = 0.313; F = 49.92, p < 0.001). Among the predictors, perceived economic impact emerged as the strongest determinant (β = 0.30, t = 4.38, p < 0.001), followed closely by social–environmental perceptions (β = 0.25, t = 5.15, p < 0.001).

Table 6.

Regression results predicting residents’ positive attitude toward tourism (residents).

Additional analyses confirmed the robustness of the resident model. Partial R2 values indicated that perceived economic impact explained around 16% of the variance in attitudes, while perceived social–environmental impact added about 15%. Residuals followed an approximately normal distribution, variance inflation factors were below 2.0, and tolerance values exceeded 0.5, suggesting no multicollinearity concerns. The residual plots did not indicate heteroskedasticity, and the model thus met the key assumptions of linear regression. These results reinforce that residents’ attitudes are shaped primarily by economic and social–environmental considerations in a balanced manner.

These findings indicate that residents’ positive attitude toward tourism in Piraeus is grounded primarily in their recognition of tourism’s contribution to the local economy and its social–environmental benefits, confirming hypotheses H5 and H6. In contrast to hypothesis H7, negative environmental concerns did not emerge as significant deterrents; instead, residents evaluated tourism positively when its economic and social advantages outweighed potential costs, in line with hypothesis H8.

These results highlight that residents’ positive attitude toward tourism in Piraeus is shaped primarily by its perceived economic contributions (e.g., job creation, support for local businesses, etc.), together with its social and cultural benefits. While residents are aware of environmental pressures, these do not significantly undermine their positive evaluation of tourism. Instead, the perceived advantages in terms of economic vitality and community well-being outweigh potential costs, leading to an overall supportive approach toward tourism development.

6. Discussion

The findings of this study provide important insights into how visitors and residents of Piraeus perceive sustainability in tourism, and how these perceptions shape satisfaction and support for tourism development. This dual-sample approach allows for a direct comparison between the demand side and the host community, contributing to the ongoing debate on how to reconcile short-term visitor expectations with long-term community well-being (Farmaki, 2020; Cocuzza et al., 2025).

For visitors, results confirm the role of environmental and social dimensions in shaping overall satisfaction. The results on perceived environmental impact confirm prior research, highlighting the importance of cleanliness, pollution control, and sustainability practices in urban port destinations (Abbasi et al., 2023; Breiby & Slåtten, 2018). Similarly, social and cultural interactions emerged as issues lead to satisfaction, aligning with studies showing that authentic cultural experiences and hospitality increase visitor satisfaction and loyalty (Christou et al., 2018; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2022). In contrast, the perceived economic impact aspects, such as value-for-money, played only a marginal role. This finding resonates with the literature suggesting that visitors to cruise ports, while sensitive to prices, ultimately prioritize quality experiences and environmental integrity (Jarvis et al., 2016). Thus, hypotheses H1, H2, and H4 were confirmed, while H3 received only partial support.

For residents, the results point to a more differentiated perspective. Both perceived economic and social–environmental impacts significantly affected positive attitudes toward tourism, with economic contributions having the strongest influence. This pattern supports existing evidence that residents’ willingness to support tourism is closely tied to tangible benefits, such as job creation and local business activity (Gursoy et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2018). At the same time, the significant role of social–environmental perceptions suggests that residents also value improvements in cultural vitality and community quality of life, consistent with Stylidis et al. (2014) and Kodaş et al. (2022). Interestingly, negative environmental concerns (H7) were not found to significantly prevent residents’ support. Instead, residents’ attitudes appear to reflect a cost–benefit approach, where the advantages of economic vitality and community cohesion outweigh concerns about congestion or pollution, in line with hypothesis H8 and recent findings in similar urban contexts (Çelik & Rasoolimanesh, 2023).

Overall, these findings contribute to theoretical debates on sustainable tourism governance in port cities. The contrast between visitors’ experience-driven orientation and residents’ benefit-driven evaluation highlights the need for governance frameworks that integrate multiple, and sometimes diverging, stakeholder priorities (Panse et al., 2021; Pechlaner et al., 2025). In Piraeus, sustainable destination planning cannot rely only on boosting visitor satisfaction through improved services and environmental management. It must also deliver inclusive economic and social benefits to maintain resident support. Additionally, this study illustrates how aligning visitors’ sustainability-sensitive expectations with residents’ benefit-oriented support can foster a more resilient tourism ecosystem. In doing so, it reinforces calls for multi-stakeholder governance in port cities that ensures economic viability, social inclusiveness, and environmental stewardship as mutually reinforcing pillars of destination resilience.

From a policy perspective, the results suggest several implications. First, destination managers should prioritize environmental quality initiatives, such as waste reduction, air quality control, and sustainable mobility, since these are central to visitors’ satisfaction and competitiveness. Second, inclusive community engagement strategies are necessary to ensure that residents perceive themselves as beneficiaries of tourism growth. This includes promoting local entrepreneurship, investing in cultural infrastructure, and integrating residents into participatory governance structures, thereby enhancing transparency and trust (Leon et al., 2022; Cocuzza et al., 2025). Finally, governance strategies should address the tension between short-term tourism expansion and long-term sustainability by adopting adaptive management approaches that balance competing interests (Amore et al., 2018).

7. Conclusions

This study examined how visitors and residents of Piraeus perceive the sustainability dimensions of tourism and how these perceptions shape satisfaction and support for tourism development. By adopting a dual-sample approach, this research provides a holistic perspective that integrates demand-side and community-side views, thereby contributing to the broader discourse on sustainable destination planning in port cities (Farmaki, 2020; Cocuzza et al., 2025).

The results reveal that visitors’ satisfaction is shaped primarily by environmental quality and social–cultural interactions, while residents’ support for tourism depends most strongly on perceived economic benefits and community-oriented social–environmental gains. Negative environmental concerns, while acknowledged, did not significantly reduce residents’ support. These findings highlight the differentiated salience of sustainability dimensions for each group: visitors prioritize experiential and environmental quality (Paraskevopoulou et al., 2019; Breiby & Slåtten, 2018), while residents focus on tangible benefits and community well-being (Gursoy et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2018).

Theoretically, this study advances sustainability theory and stakeholder theory by confirming that the three pillars of sustainability exert asymmetric effects across stakeholder groups. Visitors’ emphasis on environmental and experiential quality, contrasted with residents’ prioritization of economic and community-oriented gains, illustrates the need for governance approaches that integrate sustainability pillars while reconciling diverse stakeholder perspectives. The confirmation of relative-strength hypotheses (H4 and H8) underscores the need for weighted models of sustainability rather than uniform assumptions about stakeholder priorities (Jarvis et al., 2016; Kodaş et al., 2022). Empirically, this study adds evidence from a Mediterranean port city, expanding the limited literature on urban maritime tourism governance and resilience (Traskevich & Fontanari, 2023; Fabry & Zeghni, 2019).

From a policy perspective, the findings point to the importance of integrated governance strategies that balance the needs of visitors and residents. For Piraeus, this entails investing in environmental quality and service improvements to maintain competitiveness (Abbasi et al., 2023), while ensuring that economic gains and cultural vitality are shared with the community to secure resident support (Stylidis et al., 2014; Leon et al., 2022). More broadly, the study reinforces the necessity of multi-stakeholder governance models that enhance transparency, participation, and adaptive management in port destinations (Amore et al., 2018; Cocuzza et al., 2025).

Future research could extend this framework to other port cities for comparative insights, employ longitudinal designs to capture changing perceptions over time, and integrate objective sustainability indicators with stakeholder perceptions. Such approaches would further refine our understanding of the complex trade-offs and synergies that underpin sustainable and resilient tourism in urban maritime contexts (D. Nguyen et al., 2016; Ettorre et al., 2023).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.G., I.K., E.K., S.V., A.S., I.A., C.K., N.K., and G.T.; methodology, N.G., I.K., E.K., S.V., A.S., I.A., C.K., N.K., and G.T.; validation, N.G., I.K., E.K., S.V., A.S., I.A., C.K., N.K., and G.T.; formal analysis, N.G., I.K., E.K., S.V., A.S., I.A., C.K., N.K., and G.T.; investigation, N.G., I.K., E.K., S.V., A.S., I.A., C.K., N.K., and G.T.; resources, N.G., I.K., E.K., S.V., A.S., I.A., C.K., N.K., and G.T.; data curation, N.G., I.K., E.K., S.V., A.S., I.A., C.K., N.K., and G.T.; writing—original draft preparation, N.G., I.K., E.K., S.V., A.S., I.A., C.K., N.K., and G.T.; writing—review and editing, N.G., I.K., E.K., S.V., A.S., I.A., C.K., N.K., and G.T.; visualization, N.G., I.K., E.K., S.V., A.S., I.A., C.K., N.K., and G.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project (Tourism Knowledge Base for Socio-Economic and Environmental Data Analysis—TOUKBASEED) was carried out within the framework of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan Greece 2.0, funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU (Implementation body: HFRI), under the GA number 16796. This work has been also partly supported by the University of Piraeus Research Center.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of University of Piraeus (protocol code 15/2025 with approval date: 26 March 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. Restrictions apply due to privacy, legal, and ethical considerations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abbasi, M., Abbasi, G., & Mohammadloo, M. (2023). Analyzing the environmental quality of urban tourism attractions and modeling its effects on tourists’ satisfaction (case study: Zanjan city). Geography and Territorial Spatial Arrangement, 13(49), 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelmalak, F. (2024). Smart tourism destinations: Governance and resilience the use of ICTs in destination governance and its impact on resilience. Journal of Smart Tourism, 4(2), 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrwajfah, M. M., Almeida-García, F., & Cortés-Macías, R. (2019). Residents’ perceptions and satisfaction toward tourism development: A case study of Petra Region, Jordan. Sustainability, 11(7), 1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amore, A., Prayag, G., & Hall, C. M. (2018). Conceptualizing destination resilience from a multilevel perspective. Tourism Review International, 22(3–4), 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulou, A., & Poulou, M. (2017). Sustainable urban freight distribution: The case of Piraeus port-city. Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning, 2(4), 110–116. [Google Scholar]

- Anastasopoulos, I., Georgopoulos, N., Katsanakis, I., Klada, N., Konstantopoulou, C., Kopanaki, E., Klada, N., Tsoupros, G., & Varelas, S. (2024). Management of sustainable tourism in tourist destination ports: The use of sustainable indicators in the case study of Piraeus port, Greece. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment, 263, 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Andereck, K. L., Valentine, K. M., Knopf, R. C., & Vogt, C. A. (2005). Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(4), 1056–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M. J., Costa, J. P., & Jiménez-Morales, E. (2021). Challenges for European tourist-city-ports: Strategies for a sustainable coexistence in the cruise post-COVID context. Land, 10(11), 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakogiannis, E., Vassi, A., Christodoulopoulou, G., & Siti, M. (2018). Bike sharing systems as a tool to increase sustainable coastal and maritime tourism. The case of Piraeus. Regional Science Inquiry, 10(3), 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Breiby, M. A., & Slåtten, T. (2018). The role of aesthetic experiential qualities for tourist satisfaction and loyalty. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 12(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H. T., Jones, T. E., Weaver, D. B., & Le, A. (2020). The adaptive resilience of living cultural heritage in a tourism destination. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(7), 1022–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. W. (1999). Sustainable tourism: A state-of-the-art review. Tourism Geographies, 1(1), 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, E. T. (2007). Stakeholders in sustainable tourism development and their roles: Applying stakeholder theory to sustainable tourism development. Tourism Review, 62(2), 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C. S., Nozu, K., & Zhou, Q. (2020). Tourism stakeholder perspective for disaster-management process and resilience: The case of the 2018 Hokkaido Eastern Iburi Earthquake in Japan. Sustainability, 12(19), 7882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charag, A. H., Fazili, A. I., & Bashir, I. (2021). Residents’ perception towards tourism impacts in Kashmir. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 7(3), 741–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christou, P., Sharpley, R., & Farmaki, A. (2018). Exploring the emotional dimension of visitors’ satisfaction at cultural events. Event Management, 22(2), 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocuzza, E., Le Pira, M., Ignaccolo, M., & Inturri, G. (2025). Towards a sustainable governance of port systems and port cities: A stakeholder engagement approach. Transportation Research Procedia, 90, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, S., & Rasoolimanesh, S. M. (2023). Residents’ attitudes towards tourism, cost–benefit attitudes, and support for tourism: A pre-development perspective. Tourism Planning & Development, 20(4), 522–540. [Google Scholar]

- Della Corte, V., Del Gaudio, G., Sepe, F., & Luongo, S. (2021). Destination resilience and innovation for advanced sustainable tourism management: A bibliometric analysis. Sustainability, 13(22), 12632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettorre, B., Daldanise, G., Giovene di Girasole, E., & Clemente, M. (2023). Co-planning port–city 2030: The InterACT approach as a booster for port–city sustainable development. Sustainability, 15(21), 15641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabry, N., & Zeghni, S. (2019). Resilience, tourist destinations and governance: An analytical framework. In F. Cholat, L. Gwiazdzinski, C. Tritz, & J. Tuppen (Eds.), Tourismes et adaptations (pp. 96–108). Elya Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Farmaki, A. (2020). Regional network governance and sustainable tourism. In Tourism and sustainable development goals (pp. 192–214). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS (3rd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Galani, K. (2025). Industrialisation, globalisation and the emergence of new port cities: A case study of Piraeus. In The Routledge history of the modern maritime world since 1500 (pp. 178–193). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Georgousi, D. (2022). Stakeholder management of the environment [Master’s thesis, University of Piraeus]. [Google Scholar]

- Gnanapala, W. A. (2015). Tourists perception and satisfaction: Implications for destination management. American Journal of Marketing Research, 1(1), 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Govindarajo, N. S., & Khen, M. H. S. (2020). Effect of service quality on visitor satisfaction, destination image and destination loyalty–practical, theoretical and policy implications to avitourism. International Journal of Culture Tourism and Hospitality Research, 14(1), 83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy, D., Ouyang, Z., Nunkoo, R., & Wei, W. (2019). Residents’ impact perceptions of and attitudes towards tourism development: A meta-analysis. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 28(3), 306–333. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J., Page, M., & Brunsveld, N. (2020). Essentials of business research methods (4th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jarratt, D., & Davies, N. J. (2020). Planning for climate change impacts: Coastal tourism destination resilience policies. Tourism Planning & Development, 17(4), 423–440. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, D., Stoeckl, N., & Liu, H. B. (2016). The impact of economic, social and environmental factors on trip satisfaction and the likelihood of visitors returning. Tourism Management, 52, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, M. M., Kang, M., & Desmarais, E. (2016). Residents’ perceived quality of life in a cultural-heritage tourism destination. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 11(1), 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, W., & Loang, O. K. (2024). China’s cultural tourism: Strategies for authentic experiences and enhanced visitor satisfaction. International Journal of Business and Technology Management, 6(1), 566–575. [Google Scholar]

- Kodaş, D., Arıca, R., Kafa, N., & Duman, F. (2022). Relationships between perceptions of residents toward tourism development, benefits derived from tourism and support to tourism. Journal of Tourismology, 8(2), 255–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinos, K., Nikas, A., Daniil, V., Kanellou, E., & Doukas, H. (2023). A multi-criteria decision support framework for assessing seaport sustainability planning: The case of Piraeus. Maritime Policy & Management, 50(8), 1030–1056. [Google Scholar]

- Leon, C. J., Lam González, Y. E., Ruggieri, G., & Calò, P. (2022). Assessing climate change adaptation and risk management programmes: Stakeholder participation process and policy implications for transport, energy and tourism sectors on the island of sicily. Land, 11(8), 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R., Peng, L., & Deng, W. (2019). Resident perceptions toward tourism development at a large scale. Sustainability, 11(18), 5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liasidou, S., Stylianou, C., Berjozkina, G., & Garanti, Z. (2021). Residents’ perceptions of the environmental and social impact of tourism in rural areas. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 13(6), 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z., Chen, Y., & Filieri, R. (2017). Resident-tourist value co-creation: The role of residents’ perceived tourism impacts and life satisfaction. Tourism Management, 61, 436–442. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Melgarejo, A., García-Valenzuela, L. J., Hilliard, I., & Pinto-Tortosa, A. J. (2019). Exploring relations between heritage interpretation, visitors learning experience and tourist satisfaction. Czech Journal of Tourism, 8(2), 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D., Imamura, F., & Iuchi, K. (2016). Disaster management in coastal tourism destinations: The case for transactive planning and social learning. International Review for Spatial Planning and Sustainable Development, 4(2), 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nguyen, T. N., & Huynh, V. D. (2024). Exploring the impact of tourism environment on tourist satisfaction in tourist sites: An example of phong dien tourism village, Vietnam. Case Studies in the Environment, 8(1), 2281531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panse, G., Fyall, A., & Alvarez, S. (2021). Stakeholder views on sustainability in an urban destination context: An inclusive path to destination competitiveness. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 7(4), 895–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraskevopoulou, A., Georgi, N. T. J., Oikonomou, A., Mariaki, E., & Paraskevas, A. (2019, July). Examining the opportunities for nature-based solutions at the Municipality of Piraeus. In IOP conference series: Earth and environmental science (Vol. 296, p. 012003). IOP Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Pechlaner, H., Philipp, J., & Olbrich, N. (2025). Destination governance: The new role of destination management, stakeholder networks and sustainability. In Handbook on tourism governance (pp. 94–115). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Pinhal, R., Estima, A., & Duarte, P. (2025). Open innovation in the tourism industry: A systematic review. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(3), 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platias, C., & Spyrou, D. (2023). EU-Funded energy-related projects for sustainable ports: Evidence from the port of Piraeus. Sustainability, 15(5), 4363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponsignon, F., & Derbaix, M. (2020). The impact of interactive technologies on the social experience: An empirical study in a cultural tourism context. Tourism Management Perspectives, 35, 100723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Seyfi, S., Rather, R. A., & Hall, C. M. (2022). Investigating the mediating role of visitor satisfaction in the relationship between memorable tourism experiences and behavioral intentions in heritage tourism context. Tourism Review, 77(2), 687–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez del Rio-Vazquez, M. E., Rodríguez-Rad, C. J., & Revilla-Camacho, M. A. (2019). Relevance of social, economic, and environmental impacts on residents’ satisfaction with the public administration of tourism. Sustainability, 11(22), 6380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, S. C., Kelkar, V., & Sankaran, V. (2019). Resilient coastal cities for enhancing tourism economy: Integrated planning approaches (ADBI Working Paper Series No. 1043). Asian Development Bank Institute.

- Santos, M., Radicchi, E., & Zagnoli, P. (2019). Port’s role as a determinant of cruise destination socio-economic sustainability. Sustainability, 11(17), 4542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoldi, F. (2025). Geographies and counter-geographies of global circulation in port cities–the case of Piraeus. Urban Geography, 46, 1757–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmelev, S. E., Agbleze, L., & Spangenberg, J. H. (2023). Multidimensional ecosystem mapping: Towards a more comprehensive spatial assessment of nature’s contributions to people in France. Sustainability, 15(9), 7557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmelev, S. E., Sagiyeva, R. K., Kadyrkhanova, Z. M., Chzhan, Y. Y., & Shmeleva, I. A. (2018). Comparative sustainability analysis of two Asian cities: A multidimensional assessment of Taipei and Almaty. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 5(3), 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. (2021). Sharing and platform economy in tourism: An ecosystem review of actors and future research agenda. In U. Gretzel, W. Fuchs, & M. Sigala (Eds.), Handbook of e-tourism (pp. 1–23). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H., Zhu, C., & Fong, L. H. N. (2021). Exploring residents’ perceptions and attitudes towards sustainable tourism development in traditional villages: The lens of stakeholder theory. Sustainability, 13(23), 13032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D., Biran, A., Sit, J., & Szivas, E. M. (2014). Residents’ support for tourism development: The role of residents’ place image and perceived tourism impacts. Tourism Management, 45, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traskevich, A., & Fontanari, M. (2023). Tourism potentials in post-COVID19: The concept of destination resilience for advanced sustainable management in tourism. Tourism Planning & Development, 20(1), 12–36. [Google Scholar]

- Velmurugan, S., Thazhathethil, B. V., & George, B. (2021). A study of visitor impact management practices and visitor satisfaction at Eravikulam National Park, India. International Journal of Geoheritage and Parks, 9(4), 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C. P., Cole, S. T., & Chancellor, C. (2018). Resident support for tourism development in rural midwestern (USA) communities: Perceived tourism impacts and community quality of life perspective. Sustainability, 10(3), 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F., Lv, Y., & Sarker, M. N. I. (2024). Resilience and recovery: A systematic review of tourism governance strategies in disaster-affected regions. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 103, 104350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).