Abstract

In the tourism industry, loyalty is a crucial factor that can significantly impact a business’s success and survival. In niche markets such as wine and beer, it is even more relevant, as in Mexico, most businesses are small and medium-sized enterprises. This study aimed to compare the influence of experience and price on tourist loyalty between wine and beer, using a sample of 245 adult tourists in Baja California, Mexico. Structural equation modeling using partial least squares (PLS) was employed for data analysis, utilizing an embedded two-stage approach. It was found that there is no significant difference in the influence of experience and price on loyalty, regardless of the type of beverage being consumed. In both cases, price is the variable that most influences tourist loyalty, although the influence of experience on loyalty is also significant but only for beer. These results enable the development of targeted marketing strategies for regions that focus on gastronomic tourism centered on these types of beverages. In addition to practitioners concentrating on developing a sensory, affective, and behavioral experience for tourists, it is also essential to set an attractive price for the consumer.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, Baja California, Mexico, has stood out for its diversity in the development of wine and craft beer tourism. The renowned wine-producing region is gaining increasing importance in terms of tourism and the economy. This dynamic environment requires an understanding of how consumers experience the sensory aspects of consuming wine or beer, how they perceive its price, and the extent to which they retain a brand. This is a key factor in the development and positioning of the region’s economy. The consumer experience not only determines purchasing decisions but also influences assessments of quality and price. Ultimately, brand loyalty, defined as consistent behavior over time, is crucial for business sustainability and competitive advantage.

Specifically, Ensenada is considered a key driver of regional growth in the Guadalupe Valley, known as the “Wine Route,” as it accounts for 70% of wine production and has become an international benchmark (Moreno-Ortiz, 2025). In parallel, the rise of craft beer has placed cities such as Tijuana, Mexicali, and Ensenada among the most significant hubs in this industry in Latin America (Meraz Ruiz et al., 2022). Both ecosystems share a narrative of differentiation based on the sensory and symbolic experience of consumption, pricing strategies that seek to capture perceived value through quality and origin, and the need to translate these perceptions into sustained loyalty. Recent studies on wine tourism show that variables such as hedonic motivation, perceived value, and satisfaction firmly explain the intention to visit (Leyva-Hernández & Toledo-López, 2024). The results show that, beyond the product, the overall experience of the destination is also evaluated. It is an element that determines the future behavior of the wine consumer.

At the same time, the Mexican literature on craft beer documents differentiating attributes valued by consumers: aroma, variety, pairings, local identity, and their intention to purchase in Tijuana (Plaza Fiesta) and Mexicali, where digital communication from microbreweries acts as a catalyst for preference and repeat purchases (Meraz Ruiz et al., 2022; Espinoza-Córdova et al., 2024). Field research in Tijuana identifies sensory quality, availability, price, and the location of the point of sale as key factors in the selection process, while in Mexicali, the use of social media, email marketing, and audiovisual content is associated with indicators of engagement and loyalty (Espinoza-Córdova et al., 2024).

From a wine and beer tourism perspective, the experience can go beyond simply tasting the wine, also considering elements such as the context of the place, its history, culture, contact with employees, and learning opportunities. These indicators demonstrate an important value that helps reinforce consumer identity and emphasize brand or destination loyalty (Pine & Gilmore, 2019; Hall et al., 2023). Furthermore, a structured experience promotes satisfaction, recommendations, and repeat purchases, which are clear elements of loyalty (Oliver, 2015). Where cost can be a barrier, the experience is viewed as a strategic differentiator that can support higher prices and boost the perception of quality, which is important for the sustainability of small and medium-sized businesses in the tourism and agroindustrial sectors.

The literature paints a picture of the importance of experience and prices as determining factors for tourist loyalty in agri-food products and beverages: experience influences satisfaction and the value of user perception (Pine & Gilmore, 2019; Wu et al., 2020), followed by cost representing a signal of fairness and quality when presenting the purchase decision (Zeithaml, 1988). However, most of these studies focus on wine tourism, where wine has been conceptualized as a cultural and heritage product (Carlsen & Charters, 2018). In contrast, research on craft beer in Mexico and Latin America has focused more on productive aspects, local identity, or emerging consumption (Gómez & García, 2020), leaving unexplored how the combination of sensory experience and price perception shapes loyalty in these consumers. Therefore, the novelty of this study lies in its parallel comparison of both sectors in Baja California under a single design, which will allow us to identify similarities, divergences, and hybrid dynamics that currently remain invisible to tourism theory and practice.

Price, specifically, becomes important in Mexico, where buyers are sensitive to the relationship between quality and cost, and where competition in food markets is influenced by factors such as disposable income, additional tourist offerings, and the perception of product exclusivity (Wu et al., 2020). At the same time, experience has taken on a key role as an element that helps create value beyond the physical product, incorporating sensory (tastings, combinations, fragrances), emotional (culture, customer service), and behavioral (socialization, learning) aspects that can influence customer satisfaction and loyalty (Pine & Gilmore, 2019; Hall et al., 2023).

Stone (2023) analyzed the differences between beer tourists and wine tourists, demonstrating the segmentation of consumer profiles linked to alcoholic beverages, highlighting how motivations and experiences construct distinct identities in gastronomic tourism. In contrast, the study by Gómez-Corona et al. (2017) focuses on the cultural and everyday consumption of beer in Mexico, comparing habits and attitudes toward craft and industrial beer. This reveals how consumers’ symbolic and emotional perceptions determine product choice beyond its utilitarian function. While the former is located in the realm of tourism and travel as a leisure experience, the latter emphasizes the construction of meanings around the beverage in local contexts of consumption and social belonging.

On the other hand, Trejo-Pech et al. (2012), in their study of the Baja California wine industry, shift the discussion to a structural and economic level, examining whether wine production in the region constitutes a cluster capable of generating local development. In contrast to the other works, this study does not address the individual motivation of the consumer or tourist, but rather the dynamics of competitiveness and business collaboration that strengthen a sector. In this way, the three studies allow for a reflective contrast: beer and wine tourism is fueled by experience-seeking travelers (Stone, 2023); the consumption of craft and industrial beer in Mexico, with the cultural and symbolic motivations that consumers develop in their daily lives is rooted in cultural meanings and social practices; and the wine industry in Baja California (Trejo-Pech et al., 2012) is configured as an economic phenomenon with territorial implications. It can be appreciated that tourism and the consumption of beverages such as beer and wine cannot be analyzed solely from a tourist, cultural, or economic perspective, but rather as interrelated phenomena that shape the dynamics of identity, market, and territory.

How do experience and price modify consumer loyalty to beer and wine in Baja California?

In Baja California, the main characteristics are a concentration of producers, the presence of local value chains, and a positive impact of wine tourism (wine route) on regional promotion, but also challenges (predominant size of small wineries, costs of imported inputs, technological limitations) that limit the complete consolidation of the cluster. The theoretical gap lies in the limited articulation between experience, price perception, and the construction of loyalty in the wine and craft beer sector. Although studies recognize that experience represents a strategic differentiator that drives loyalty, satisfaction, recommendation, repurchase, and price can function as a signal of equity and quality in consumption decisions. This study aims to compare the influence of experience and price on tourist loyalty between wine and beer. Baja California presents itself as a natural field of study for research, as it unites winemaking heritage with the growth of craft beer, in an environment where small and medium-sized tourism businesses coexist (Cabrera-Flores et al., 2019). In this context, understanding the relationships between loyalty, costs, and experiences in this region will not only enrich the academic debate but also provide helpful information for the development of public policies and marketing strategies that promote sustainable local growth. In turn, it will provide practical contributions to those involved in the tourism sector, including producers and entrepreneurs, who will find more effective ways to attract and retain tourists by offering unique experiences and competitive prices.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sensory Experience

In the tourism industry, the customer experience has become a vital topic in marketing; it covers multiple aspects: sensory, emotional, and behavioral. Each influences tourists’ perceptions when selecting destinations and services. When discussing sensory experiences, we refer to the physical perceptions tourists have through their five senses (Yactayo-Moreno & Vargas-Merino, 2021). According to Casals (2014), engaging the senses sparks an experience in the consumer; these experiences can include tasting foods or interacting with packaging design. Sensory marketing aims to go beyond traditional advertising by highlighting the values and unique features of products and services (Ortegón-Cortázar & Rodríguez, 2017).

The sense of smell is one of the most sensitive and emotional senses because it allows us to connect specific odors with experiences. Smell gives consumers initial information about a product. It plays a key role in influencing purchasing decisions; in this way, it helps us choose what to buy accurately and contextually, which is essential for attracting consumers. The participation and combination of the senses help enhance the consumer’s experience while also highlighting the product’s value proposition (Gómez Gallo & Hernández Zelaya, 2020; Ortegón-Cortázar & Rodríguez, 2017).

Sensory experiences among beer and wine consumers in Baja California enhance perceptions of quality, gastronomic pleasure, and overall satisfaction. Visitors report high sensory enjoyment during tastings, perceive good value for money, and feel connected to local cuisine. These experiences include not only taste but also learning about wine production and culture, which deepens both the sensory and emotional engagement (Bustamante-Lara et al., 2023; Leyva-Hernández & Toledo-López, 2024; Hernández et al., 2022).

Wine consumers tend to have experiences that focus more on the cognitive aspect, while occasional consumers emphasize the sensory and affective aspects. According to Gómez-Corona et al. (2017), the drinking experience is shaped by the interaction of sensory, affective, and cognitive factors, which influence the consumption process; other factors, such as attitudes, consumption habits, personal or social context, purchasing experiences, and perceived benefits of the product, also impact the experiences. However, these are more significant before and after the act of consumption.

Sensory experiences in beer drinking are emphasized at beer events and routes; these experiences are heightened by attention, focus, and the “flow” during tasting, which enhances the effect on consumer loyalty and satisfaction, highlighting the importance of sensory and social aspects of their consumption (Guerra-Tamez & Franco-García, 2022).

Although the literature has examined the tourist experience on the wine and beer routes of Baja California, a significant gap remains in sensory and comparative analysis. Current studies lack direct comparisons between the sensory experiences of both routes and do not utilize advanced methods, such as tasting panels or neuroscientific techniques, to better understand consumer perception. Most research is cross-sectional, which limits the understanding of how experiences change over time. Additionally, there is limited focus on how digitalization, detailed consumer segmentation, and sensory education influence perception and loyalty, leaving much room for future research (Leyva-Hernández & Toledo-López, 2024; Wang et al., 2024; Carmer et al., 2024; Hernández et al., 2022).

In conclusion, drinking beer or wine involves sensory aspects (aroma, flavor, and body), emotional elements (moods), and cognitive factors (expectations, knowledge) (Sáenz-Navajas et al., 2024; Oyinseye et al., 2022).

2.2. Affective and Behavioral Experience

Tourist consumption behavior describes the active process by which tourists select and purchase travel products. These steps aim to satisfy needs, make decisions, use services, and review experiences afterward, all influenced by internal factors like motivations, values, and emotions, as well as external factors such as culture, reference groups, and marketing (Li & Cao, 2022; Dixit, 2021). Customer behavior emphasizes sensory, emotional, and social experiences; these experiences benefit the company and build customer loyalty (Ward & Gshayyish, 2024).

Tourist activities along wine and beer routes create intense emotional experiences because they evoke positive feelings like relaxation and euphoria; they also connect visitors with the landscape, culture, and heritage of the region. These activities foster emotional bonds with visitors (Cristófol et al., 2021; Kastenholz et al., 2022; Dias et al., 2023). In the beer context, total immersion is a key element that deepens the emotional experience and directly influences consumer behavior. Perceived satisfaction, tasting quality, and linking to the region’s identity are essential for increasing loyalty, the intention to return, and word-of-mouth recommendations (Bustamante-Lara et al., 2023; Leyva-Hernández & Toledo-López, 2024; Guerra-Tamez & Franco-García, 2022).

On the other hand, the territorial brand highlights destinations and how they build and communicate a unique identity by utilizing local products, traditions, and landscapes to stand out. For example, Cristófol et al. (2021) point out how wineries in British Columbia use events to incorporate local identity into their brand, thereby creating a stronger connection with visitors and enhancing the region’s reputation (Cristófol et al., 2021; Molleví et al., 2020).

Hernández-Mora et al. (2022) emphasize that evaluating experience is a valuable tool for understanding consumer behavior because it gives a competitive advantage as companies craft experiences that differentiate them in the market. A clear example is beer, which is associated with various attitudes that can generate positive or negative emotions, affecting the consumer’s mood and making it an ideal product for analyzing the consumer experience.

Authors such as Hernández-Mora et al. (2022) and Silva (2017) mention that the consumption of beer and wine is linked to positive emotions such as relaxation, pleasure, and joy; these emotions can vary. In the case of beer, high-activation emotions are elicited, while for wine, low-activation emotions are associated. Mood also influences beverage choice; for example, positive feelings are connected to the consumption of wine and beer, while negative feelings are linked to spirits (whiskey, brandy, gin) (Vasileiou et al., 2024).

2.3. Tourist Loyalty

Recent studies indicate that the consumer experience significantly impacts brand loyalty, which applies to the consumption of specific beverages. Jannah and Fadli (2023) emphasize that brand satisfaction influences loyalty; thus, consumer satisfaction and experience are essential for building loyalty. Companies should focus on these two factors to enhance product quality and provide excellent service.

Moane et al. (2020) identified four key factors that influence brand loyalty: awareness, quality, personality, and physical attributes (including sensory characteristics, flavor, ingredients, and presentation). This analysis confirms that these dimensions are connected to consumer loyalty. Brand awareness can significantly impact advertising efforts by strengthening the emotional connection and trust consumers have with the brand (Pérez Ricardo et al., 2023).

Wine consumer loyalty is essential for companies because loyal customers tend to purchase the same product again, reducing the costs of acquiring new customers. Furthermore, these customers may spend more than initially expected, helping to safeguard the company’s market share.

Experience is a vital strategy for fostering customer loyalty and retention; this emotional component of the consumer experience highlights the feelings evoked during consumption (Núñez, 2022). Today, companies aim to deliver memorable experiences to add value. It also emphasizes that interactive social networks generate value and emotional bonds, which influence how tourists engage with and emotionally connect to the destination.

2.4. Price and Perceived Value

Price is a factor that influences purchasing decisions. According to Giraldo Oliveros et al. (2021), it is seen as an objective measure for maximizing utility and benefits; for the author, money represents the amount a consumer must pay to acquire a product or service. This idea has been expanded to include the concept of price as a market stimulus that elicits cognitive, emotional, and behavioral responses in consumers.

Consumers’ cultural identity affects how they associate price with product quality; this connection is crucial during purchases because it acts as an indicator when quality is not visible (Yang et al., 2019). When targeting consumers with a local identity, strategies that emphasize price as a quality signal are necessary, while for those with a global identity, highlighting product features that show quality is essential.

Kalyanaram and Winer (2022) explain that price functions as a behavioral response, signaling perceptions of value and quality. Consumers interpret this signal based on their past experiences, social context, and internal standards. From this perspective, the consumer’s reaction to price is complex because it goes beyond simple cost comparison. Consumers rely on reference prices with acceptance thresholds. They may show loss aversion, reacting differently to price increases or decreases, which directly affects satisfaction and the likelihood of repurchase, thereby influencing loyalty (Kalyanaram & Winer, 2022). Other factors, such as familiarity with the product, prior knowledge, and sensory experience, also affect price sensitivity and willingness to pay.

Therefore, price is a crucial factor in how consumers perceive value; they are willing to pay more for experiences that trigger sensory and emotional responses. Another clear example related to price involves consumer loyalty to a wine brand, as mentioned by Araya-Pizarro (2022), where purchasing behavior centers on quality and price, which are the leading indicators. However, extrinsic factors such as the consumer’s age and income level also play a role.

The relationship between price and loyalty develops when consumers see the price as a sign of quality. This perception influences their satisfaction, which then boosts their commitment and trust in the brand. These factors shape customer loyalty. Customer loyalty to wines depends on satisfaction, trust, and commitment, and managing these effectively can increase consumer retention (Araya-Pizarro, 2022). Therefore, price impacts the decision to repurchase and ongoing preference for a specific brand, helping to build consumer loyalty.

When it comes to wine, consumers are generally more influenced by price than by sensory qualities. However, label details, awards, and previous tasting experiences also play a role, especially in price-sensitive markets. For example, for higher-priced wines, the origin and reputation of the winery become more important (Lozano & Arroyo, 2022).

Wine and beer tourism in Baja California has become a crucial part of the local economy, where experience, price, and customer loyalty shape consumers’ preferences in both sectors. Experiential tourism and territorial branding help explain these patterns; however, they are often studied separately in academic research. Beer routes have emerged as an experiential tourism model that extends beyond tastings, including visits to breweries, tours, and festivals. This fosters an emotional and social bond with the beer brand, leading to strong brand loyalty and repeat purchases (Guerra-Tamez & Franco-García, 2022). This approach differs from wine loyalty, which is typically more connected to quality, prestige, and personality rather than informal social or community interactions.

In conclusion, the emotional and behavioral responses of beer and wine consumers are complex because they depend on personal, situational, and product-related factors. Additionally, the literature shows that consumers tend to remain loyal to their beer and wine choices when interactions focus on sensory experiences, perceived value, and external factors like price and brand reputation. Therefore, companies should develop strategies that include memorable experiences, competitive pricing, and distinctive sensory qualities to increase loyalty and regional competitiveness (Guerra-Tamez & Franco-García, 2022; Bustamante-Lara et al., 2023; Leyva-Hernández & Toledo-López, 2024; Hernández et al., 2022).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample

To achieve the research objective, a study with an exploratory approach and a cross-sectional time dimension was proposed. A sample of 245 adult tourists in Baja California was collected. Data were collected from adults who had consumed Baja California beer or wine or visited a Baja California brewery or winery. To this end, filter questions were included in the instrument used. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants. Data collection was conducted at convenience using a structured online questionnaire via Google Forms.

To ensure a representative sample size, a statistical power analysis was performed using statistical power tables as recommended by Nitzl (2016). A medium effect size was considered, for an optimistic approximation and similar to that obtained in wine studies (Benitez et al., 2020; Leyva-Hernández & Toledo-López, 2024), a significance level of 0.05, three predictors (based on the number of formative indicators in the consumer experience), and a statistical power of 0.80. With these values, the minimum sample size was 77, which is lower than the total sample size and the sample size for each group.

The following three sociodemographic variables were included: generation, educational level, and gender. Table 1 presents the sociodemographic data for the entire sample, as well as for those who drank beer and those who drank wine.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic data.

3.2. Measures

This study used a higher-order construct called consumer experience, which was composed of three lower-order constructs: sensory, affective, and behavioral experience. Sensory experience was measured based on four organoleptic characteristics of the beverages: appearance, aroma, flavor, and aftertaste. The Santos et al. (2020) scale was adapted to measure affective and behavioral experience. The items measuring these variables are shown in Table 2. Price and loyalty were adapted from those proposed by Calvo-Porral et al. (2018). The scale used for all items was a seven-point Likert-type scale, ranging from ‘extremely dislike/strongly disagree’ to ‘agree extremely like/strongly’.

Table 2.

Items of the constructs.

3.3. Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using partial least squares structural equation modeling. This statistical technique enabled the comparison of the effects of experience and price on tourist loyalty to beer and wine through a multigroup analysis. Before PLS-SEM analysis, a pilot test was performed to validate the mediation of the scales and determine their reliability, convergent and discriminant validity, and to verify that there was no excessively abnormal distribution based on their kurtosis and skewness values (Hair et al., 2017; Leyva-Hernández et al., 2023).

In PLS-SEM, the measurement model represents the measurement of constructs; it can be reflective or formative. In the reflective model, the items represent the effects or manifestations of the construct, while in the formative model, the items represent the causes of the construct (Sarstedt et al., 2016; Hair et al., 2020). In the first scenario, causality is directed from the construct to the indicators, which exhibit a correlation. Conversely, in the second scenario, causality is directed from the indicators to the construct, resulting in a lack of correlation. Therefore, in reflective measurement models, items can be eliminated or exchanged without affecting the measurement; however, if items are eliminated in formative measurement models, the meaning of the construct is affected (Hair et al., 2020).

The experience variable was considered a higher-order construct (HOC) as it consists of three lower-order constructs (LOCs): sensory experience, affective experience, and behavioral experience. The consumer experience measurement model was reflective-formative, while for the first-order constructs, loyalty and price, the measurement model was reflective.

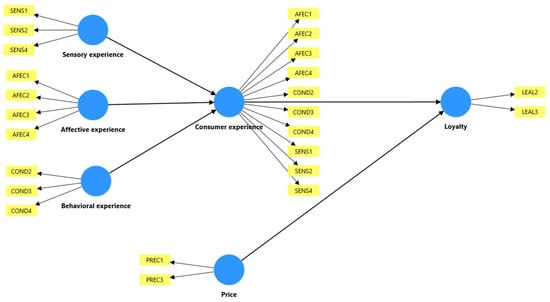

A two-stage integrated approach was used to evaluate the measurement model and the structural model, as proposed by Sarstedt et al. (2019). Under this approach, in the first stage, the HOC was constructed using the repeated indicators approach. The measurement model for the LOCs and first-order constructs was then evaluated, and scores were generated to construct the second-stage model. Figure 1 shows the model used in the first stage.

Figure 1.

First stage of the integrated approach.

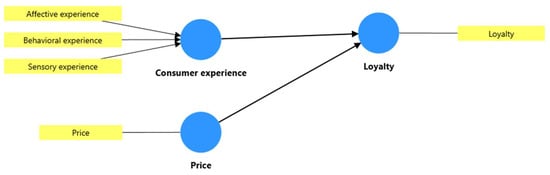

In the second stage, the model was built from the scores from the first stage, considering only one item for the first-order constructs represented by the scores (Becker et al., 2012; Sarstedt et al., 2019). In turn, the HOC (experience) was built from the LOC scores (sensory, affective, and behavioral experience). The model is illustrated in Figure 2. In this stage, the HOC measurement model and the structural model were evaluated.

Figure 2.

Second stage of the integrated approach.

The evaluation of the measurement model, as well as the structural model, was carried out according to the proposal by Benitez et al. (2020). For the reflective constructs (LOCs and first-order constructs), indicator reliability, internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity were assessed. For the formative construct (HOC), collinearity, relevance, and significance were evaluated. In evaluating the structural model, the path coefficients, coefficient of determination, model collinearity, and effect size were determined.

Because the objective was to compare the effect of the relationships between the two groups (beer and wine), a multigroup analysis was performed. To do this, it was first necessary to calculate the measurement invariance of composite models (MICOM) to corroborate the suitability for multigroup analysis. This analysis consists of three stages to test whether there is partial or complete measurement invariance, which are the confirmation of configural invariance, compositional invariance, and the equality of means and variances of the composites (Henseler et al., 2016). The existence of configural invariance was confirmed since the same items and scales were used for each of the groups. To confirm compositional invariance, a permutation analysis was performed, which corroborated that the p-value of the construct correlations was greater than 0.05, as proposed by Hair et al. (2021), thus ensuring that there are no differences between the composites. However, equality of means could not be proven; only equality of variances could be demonstrated. Therefore, partial measurement invariance was present, sufficient to perform the multigroup analysis according to Henseler et al. (2016). The multigroup analysis was performed using Bootstrap Multigroup Analysis.

3.4. Common Method Bias

When the same data collection method is used to measure different constructs, bias may exist (Podsakoff et al., 2012). To assess whether the variables measure different attributes and whether collinearity exists, a full collinearity test was conducted, which included vertical and lateral collinearity tests (Kock, 2015; Felipe et al., 2017; Leyva-Hernández et al., 2023). The vertical collinearity test was performed with the predictors proposed in the model, while the lateral collinearity test used a random variable with values between 1 and 7 as an endogenous variable (Kock & Lynn, 2012).

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Assessment

Regarding the reflective measurement model to evaluate the reliability indicator, items with factor loadings of 0.708 or greater were retained, as recommended by Guenther et al. (2023). For this reason, the items SENS1, COND1, PREC2, and LEAL1 corresponding to the constructs of sensory experience, behavior, price, and loyalty, respectively, were eliminated. Reliability values ranged from 0.708 to 0.95 (Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability), which meets the criteria suggested by Benitez et al. (2020) and Guenther et al. (2023). Furthermore, as shown in Table 3 and Table 4, the results showed that the constructs had convergent and discriminant validity since the average variance extracted (AVE) values were greater than 0.5 and the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio values were less than 0.85 (Henseler et al., 2015; Aburumman et al., 2023; Guenther et al., 2023).

Table 3.

Indicator reliability, internal consistency reliability, and convergent reliability.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity.

For the formative measurement model, the results indicated that there is no multicollinearity problem between the HOC (consumer experience) items, given that the variance inflation factor (VIF) values are less than 3 (Guenther et al., 2023). Regarding relevance and importance, the loadings and weights were evaluated (Ringle et al., 2020). The weights for affective and behavioral experience were significant; so, these LOCs were maintained. However, the weight for sensory experience was not significant, but since its loading was greater than 0.5, this item was also retained, as recommended by Sarstedt et al. (2021). These results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Evaluation of the formative measurement model.

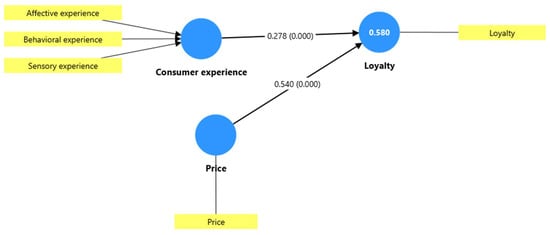

4.2. Structural Model Assessment

Through the results obtained from evaluating the structural model, it was possible to identify the factors that influence tourist loyalty in the full sample (Figure 3), specifically for beer and wine (Table 6). Differences in the significance of relationships were found since consumer experience only significantly influences loyalty in the case of beer and the full sample; however, for wine, this influence is not significant. It was also found that price was the variable that had the most significant influence on tourist loyalty in all models. These results are consistent with the effect sizes found, as the relationship between price and loyalty in the case of wine has a large effect (f2 = 0.619), greater than 0.35, as established by Benitez et al. (2020). Meanwhile, the effect size is moderate for the relationship between price and loyalty in beer (f2 = 0.224). The VIF values of the vertical collinearity test (Table 6) and the lateral collinearity test (Table 7) were less than 3, confirming that there are no multicollinearity problems (Felipe et al., 2017; Hair et al., 2019).

Figure 3.

Structural model for the full sample.

Table 6.

Structural model assessment.

Table 7.

Lateral collinearity test.

4.3. Multigroup Analysis

Prior to performing the multigroup analysis, the MICOM calculation was performed. The results are presented in Table 8. All variables presented configural invariance and compositional invariance, because the scales between groups were measured in the same way and there was no significant difference between their correlation values, as observed in Table 8. However, the equality of means could not be confirmed; only the equality of variances was corroborated. Therefore, it is assumed that there is partial measurement invariance, which, as indicated by Hair et al. (2021), is sufficient to proceed with the multigroup analysis.

Table 8.

MICOM results.

Table 9 presents the results of the multigroup analysis. It is observed that only the relationship between consumer experience and loyalty showed a significant difference between the groups, which is consistent with the results obtained from evaluating the structural model. Table 6 shows that the influence of consumer experience on loyalty is significant for beer, but not for wine, confirming the results of the multigroup analysis. It is worth noting that this confirms the effect of consumer experience on loyalty in wine is significantly greater than that in beer.

Table 9.

Multigroup analysis.

5. Discussion

The results of this research go beyond the comparative analysis of consumer behavior and offer a critique of tourism development models in Baja California based on beer and wine consumption. The findings suggest that beer tourism is constructing a “place” around authenticity, community, and product accessibility. In this regard, various studies highlight that consumers value social interaction, sensory experience, and emotional connection with the product; in some cases, also the cognitive dimension (Betancur et al., 2020; Murray & Kline, 2015). The latter is linked to consumers’ interest in knowing the geographic origin of the beer, its style, the quality of the ingredients, and the brand image, elements that strengthen the relationship with beer beyond its price (Hernández-Mora et al., 2022). This search for authenticity and connection with place is key to the experience economy, in which value is created through immersive and memorable narratives tied to cultural sustainability and territory (Richards, 2021). This model aligns with the notion of place-making, where value is generated through shared experiences and narratives of authenticity emerging from the producer and consumer community itself (Mair & Smith, 2021).

The low-price elasticity of beer shows that this product has generated experiential value that transcends its production cost, one of the core principles of the experience economy. Its accessibility reinforces this: in Baja California, a 330 mL commercial beer costs between USD 1 and USD 5 in the case of craft beers (PROFECO, 2024). Although prices vary depending on the establishment, the range remains accessible to most consumers.

In contrast, for wine consumers, experience does not have a significant influence on loyalty. In this case, price and perceived economic value are more decisive for purchase decisions. Despite the enotourism relevance of the region, the cultural connection of wine seems to rely more on complementary services—restaurants, spas, events, and lodging—than on the beverage itself (Gómez-Corona et al., 2017; Velasco et al., 2023). This situation resembles what Relph (1976) called a “superficial place,” where the experience lacks cultural depth. The high price elasticity of wine confirms this trend: consumers are not willing to pay more if they can find a similar experience at a lower cost (Parkin & Loria, 2020). This finding contributes to the debate on the experience economy by demonstrating that not all tourist experiences generate sufficient value to overcome high prices (Oh et al., 2014; Richardson, 2021). In Baja California, wine bottles range from USD 4 to USD 40, depending on the establishment (Vinito Lindo, 2025). High price elasticity reflects that, as prices increase, consumers tend to choose substitute beverages at lower cost that provide a similar experience, thereby directly affecting product loyalty.

This study reveals a contrast in loyalty mechanisms: enotourism is driven by high price elasticity and a superficial experiential value centered on complementary services (Betancur et al., 2020; Moreno-Aguilar et al., 2021), while beer tourism generates loyalty through informal spaces (Capitello & Todirica, 2021). The context of Baja California probably moderates these relationships: affordable price ranges for beer (USD 1–5), informal consumption spaces, and place-making oriented toward authenticity amplify experiential value, while in wine, dependence on complementary services and wide price dispersion (USD 4–40) promote high elasticity. The low elasticity of beer consumption diverges from national estimates for Mexico, which show a greater response (Moreno-Aguilar et al., 2021), suggesting that the local market structure in Baja California attenuates price sensitivity. This research broadens the debate on the experience economy by showing that not every experience generates loyalty to the core product. This is also evident in other products such as coffee and mass cultural tourism: although satisfactory experiences are generated, they do not translate into loyalty to the products or destinations (Estrada et al., 2024; Richardson, 2021).

Price, as a cross-cutting factor in both wine and beer, reinforces theoretical frameworks centered on perceived value and a product’s ability to explain consumer preference. Nevertheless, the literature acknowledges that experience can foster loyalty, particularly in the wine sector, where brands are a central element (Drennan et al., 2015). In beer tourism, the role of experience can be explained by the nature of consumption spaces: breweries, informal environments, and product accessibility (Capitello & Todirica, 2021). In wine tourism, some studies have shown that experience increases positive attitudes and loyalty (Hernández et al., 2022). However, this research did not identify a clear effect. A possible explanation lies in the fact that regional wine tourism, despite its cultural relevance, may be oriented toward promoting complementary services (food and lodging) of the “wine routes” rather than emphasizing wine quality, organoleptic attributes, cultural values, and experiential practices tied to wine consumption.

In terms of cultural sustainability, the beer model fosters loyalty through connection with attributes such as origin, ingredients, and accessibility, which are closely linked to territory. Thus, the experience economy becomes a vehicle for cultural preservation (DeMatos et al., 2021; Richards, 2021). Conversely, the enotourism model described here, by not anchoring the central cultural experience in the wine’s quality, history, and terroir, risks long-term sustainability (Anesi et al., 2015; Tsiakis et al., 2022). If loyalty relies primarily on generic services replicable in any destination, the unique cultural value of wine and its storytelling capacity are eroded (Gil Arroyo et al., 2023). This has already been observed in Querétaro, where wine production was promoted to create wine tourism routes, leveraging geographic proximity to Mexico City. Studies such as Bustamante-Lara et al. (2023) suggest that success in these strategies was based on complementary services valued by tourists, such as lodging and gastronomy, highlighting that consumers preferring these services often lack in-depth knowledge of enotourism.

This research contributes to the discussion on cultural sustainability by suggesting that, in Baja California, the enotourism model may be prioritizing an economic dimension (complementary services) over a deeper cultural dimension of wine. Cultural sustainability in tourism requires going beyond the mere exploitation of wine as a symbol; it entails management that authentically activates and communicates heritage values associated with production (Duxbury et al., 2021). Only the integration of these elements into solid experiential narratives can generate a value inelastic to price (Oh et al., 2014). The challenge for the sector is to design strategies that strengthen visitors’ emotional bond with wine, constructing a value proposition not dependent solely on cost (Corpus Espinoza et al., 2018; Eustice et al., 2019).

The literature on the experience economy emphasizes the need to design transformative experiences, capable of changing the visitor’s perspective and creating lasting memories that justify price premiums and consolidate loyalty (Bhardwaj et al., 2024; Gómez-Carmona et al., 2023). In Baja California, ethnographic studies show the potential to segment experiences by aesthetic or educational focus, which could contribute to more effective interventions (Velasco et al., 2023). Strategies such as visits with winemakers, guided tastings, or integration with local gastronomy can enhance the cultural value of wine (Bonn et al., 2020). In other countries, experiences centered on organoleptic characteristics such as taste and aroma have proven decisive in wine consumption, which could be replicated in Mexico. Similarly, market segmentation has been effective in the case of mezcal, where consumer profiling has enabled strategies tailored to different groups (Hernández et al., 2022; López-Rosas & Espinoza-Ortega, 2018).

Economically, wineries face the challenge of being price takers. Therefore, they must reduce production costs to offer competitive prices. The main costs lie in agronomy and bottling (Marone et al., 2017; Strub et al., 2021). This reinforces the need for integrated strategies that combine economic efficiency with high cultural value experiential offerings.

Finally, the generational profile of respondents provides additional insights. In Baja California, Generation Z shows differentiated behavior: with beer, consumption is linked to socialization, accessibility, and sensory enjoyment, reducing price sensitivity and reinforcing loyalty (Cardello et al., 2016; Corbisiero et al., 2022). At the national level, however, elasticity in beer demand has been documented (Moreno-Aguilar et al., 2021). In the case of wine, elasticity is higher and loyalty weaker; Gen Z emphasizes the price–quality relationship as a central criterion, consistent with their preference for products offering value beyond cost (Gerke, 2023; Olson & Ro, 2021). Another explanation regarding wine findings may be that Gen Z tourists are recreational or occasional wine drinkers, which limits their loyalty.

In conclusion, this study contributes to academic debates by empirically demonstrating how different place-making strategies and the valuation of experience directly impact loyalty and cultural sustainability. It suggests that experience-driven loyalty is an indicator of success in creating an authentic and culturally sustainable place, while loyalty driven primarily by price may signal a tourism offer that has not fully capitalized on its cultural capital. The main challenge is to shift from a model based on complementary services to one centered on deep cultural narratives. For wine, this implies designing immersive experiences that highlight history, organoleptic attributes, and viticultural tradition, transforming consumption into an act of learning and emotional connection (Bonn et al., 2020). Future research should include variables such as consumer profile, income, cultural identity, market segmentation, and substitute alcoholic beverages to design strategies that strengthen the cultural and economic sustainability of tourism in Baja California.

6. Conclusions

According to the proposed model, the results from partial least squares structural equation modeling showed that consumer experience and price have a positive and significant effect on tourist loyalty. However, when comparing wine and beer, consumer behaviors differed. A significant difference was found in the effect of consumer experience on loyalty between wine and beer. The most significant effect was only perceived in beer consumers, while for wine consumers, their experience did not influence their loyalty.

6.1. Theoretical Contribution

This study complements the literature in hospitality and tourism on consumer retention, particularly in explaining the factors that determine consumer loyalty. This study aligns with models and theories that explain consumer behavior, such as the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) by Ajzen (1991) and the Model of Goal-Directed Behavior (MGB) by Perugini and Bagozzi (2001). Those postulate that a person will perform a specific activity through a volitional process (TPB) and an emotional process (MGB). In this sense, it is possible to deepen this research based on these theories to explore the motivational, non-volitional, and habitual roles, incorporating the variables of subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, desire, and frequency of past behavior.

6.2. Practical Implications

These results, while facilitating the development of consumer retention strategies, are also of particular interest for the implementation of government programs that strengthen the consolidation of wine and beer-producing companies, given that price was the main factor driving consumer loyalty. It is necessary to implement public policies that enable producers to maintain competitive prices in the market, such as tax reductions or payment facilities, support for infrastructure and equipment acquisition, development of distribution channels, and other incentives that allow them to offer affordable and stable prices.

Coordination between chambers of commerce, academia, government, and businesses is essential for strengthening tourism in these regions and for developing and implementing strategies that consolidate tourist loyalty to these products. For example, as a tourist destination, it is recommended to diversify its approach by consolidating wine/beer routes, improving digital spaces for customer service (online tools), and integrating approaches to environmental protection and social responsibility. In this way, consumers can be offered differentiated added value that complements their service experience.

Although consumer experience was only significant in the case of beer, it is worthwhile to thoroughly analyze why consumers do not consider it important for maintaining consumption. It is recommended to analyze further the effect that product knowledge has on experience and loyalty. It is also necessary to analyze how it might be possible to offer a differentiating value in terms of the experience. Therefore, it is recommended that brands develop strategies to stand out in their sensory, behavioral, and affective aspects. An example of this is the dissemination of a wine culture in coordination with governments, chambers of commerce, and the business sector. This way, a wider audience will be aware of the benefits and distinctive features of locally produced wines. Furthermore, it is necessary to improve the services offered, such as diversifying experience packages at destinations by integrating tastings, guided tours, and immersive experiences. It is also possible to link local cuisine with wines to strengthen consumers’ territorial identity by implementing wine tastings with the sampling of local dishes.

6.3. Limitations of This Study and Future Lines of Research

Two of the main limitations of this research were the location of the sampling site and the period of this study. The scope of this research was limited to Baja California in a single period. While Baja California is one of the places with the highest consumption of beer and wine in Mexico, it is known that other regions in Mexico produce and consume these beverages, in addition to having seasons with greater tourist influx. Given that the explanatory power (R2) values were greater than 0.5 for the entire sample and by product, it is possible to replicate this study. It is suggested that the sample be expanded to include other states where these beverages are consumed/produced to compare other variables such as consumer income, culture, region, product variety, and territorial identity.

The scope of this study allowed for comparisons across product types; however, future studies are encouraged to compare consumption across gender, income level, and generation, as these factors may also influence consumption patterns. Furthermore, it is possible to replicate this study in other producing and consuming areas to compare the results with those of this study. In turn, this study can be replicated in the study of the consumption of other alcoholic beverages with designations of origin, such as mezcal and tequila, in the case of Mexico. In this sense, it is recommended to include designations of origin to verify whether they play a relevant role in tourist loyalty.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.N.L.-H. and L.R.-L.; methodology, S.N.L.-H.; software, S.N.L.-H.; validation, S.N.L.-H.; formal analysis, S.N.L.-H.; investigation, S.N.L.-H. and L.R.-L.; resources, S.N.L.-H. and L.R.-L.; data curation, S.N.L.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.N.L.-H., L.R.-L., O.T.B.-P. and J.M.C.-O.; writing—review and editing, S.N.L.-H., L.R.-L., O.T.B.-P. and J.M.C.-O.; visualization, S.N.L.-H.; supervision, S.N.L.-H.; project administration, S.N.L.-H.; funding acquisition, S.N.L.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Coordinación General de Investigación y Posgrado of the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California (430/3777, 29 January 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aburumman, O. J., Omar, K., Al Shbail, M., & Aldoghan, M. (2023). How to deal with the results of PLS-SEM? In B. Alareeni, & A. Hamdan (Eds.), Explore business, technology opportunities and challenges after the COVID-19 pandemic (pp. 1196–1206). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anesi, A., Stocchero, M., Dal Santo, S., Commisso, M., Zenoni, S., Ceoldo, S., Tornielli, G. B., Siebert, T. E., Herderich, M., Pezzotti, M., & Guzzo, F. (2015). Towards a scientific interpretation of the terroir concept: Plasticity of the grape berry metabolome. BMC Plant Biology, 15(1), 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araya-Pizarro, S. (2022). Valor de marca del pisco chileno: Aportes desde la región pisquera de Chile. Retos, 12(23), 139–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J. M., Klein, K., & Wetzels, M. (2012). Hierarchical latent variable models in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using reflective-formative type models. Long Range Planning, 45(5–6), 359–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez, J., Henseler, J., Castillo, A., & Schuberth, F. (2020). How to perform and report an impactful analysis using partial least squares: Guidelines for confirmatory and explanatory IS research. Information & Management, 57(2), 103168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancur, M. I., Motoki, K., Spence, C., & Velasco, C. (2020). Factors influencing the choice of beer: A review. Food Research International, 137, 109367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, S., Chopra, R., & Aw, E. C.-X. (2024). Uncorking opportunities: A bibliometric review of wine marketing literature. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 42(7), 1274–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonn, M. A., Chang, H. S., & Cho, M. (2020). The environment and perceptions of wine consumers regarding quality, risk and value: Reputations of regional wines and restaurants. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 45, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante-Lara, T., Arroyo-Cossío, A., Reyes-Barrera, D., Chávez-Hernández, M. H., Ruiz-Vargas, S., & Montoya-Moreno, B. (2023). Descriptive analysis of wine tourism in Querétaro and Baja California, Mexico. Agro Productividad, 3(16), 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Flores, M. R., León-Pozo, A., & Durazo-Watanabe, E. A. (2019). Innovation and Collaboration in the DNA of a Cultural Industry: Craft Beer in Baja California. In M. Peris-Ortiz, M. R. Cabrera-Flores, & A. Serrano-Santoyo (Eds.), Cultural and creative industries. Innovation, technology, and knowledge management. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Porral, C., Orosa-González, J., & Blazquez-Lozano, F. (2018). A clustered-based segmentation of beer consumers: From “beer lovers” to “beer to fuddle”. British Food Journal, 120(6), 1280–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capitello, R., & Todirica, I. C. (2021). Understanding the behavior of beer consumers. In R. Capitello, & N. B. Maehle (Eds.), Woodhead publishing series in consumer science and strategic marketing (pp. 15–36). Woodhead Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardello, A. V., Pineau, B., Paisley, A. G., Roigard, C. M., Chheang, S. L., Guo, L. F., Hedderley, D. I., & Jaeger, S. R. (2016). Cognitive and emotional differentiators for beer: An exploratory study focusing on “uniqueness”. Food Quality and Preference, 54, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, J., & Charters, S. (2018). Global wine tourism: Research, management and marketing. CABI. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmer, A., Kleypas, J., & Orlowski, M. (2024). Wine sensory experience in hospitality education: A systematic review. British Food Journal, 126(4), 1365–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casals, E. E. I. (2014). Marketing sensorial: Comunicación a través de los sentidos. COMeIN, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbisiero, F., Monaco, S., & Ruspini, E. (2022). Millennials, Generación Z y el futuro del turismo (Vol. 7). Channel View Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Corpus Espinoza, K. M., Meraz-Ruiz, L., & Díaz Gómez, E. R. (2018). Enoturismo en Baja California, México: Un estudio desde la perspectiva del visitante. Teoría y Praxis, 26, 97–122. Available online: https://repositorio.cetys.mx/bitstream/60000/63/1/Enoturismo%20en%20Baja%20California%2C%20M%C3%A9xico_%20un%20estudio%20desde%20la%20perspectiva%20del%20visitante.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Cristófol, F., Cruz-Ruiz, E., & Zamarreño-Aramendia, G. (2021). Transmission of place branding values through experiential events: Wine BC case study. Sustainability, 13(6), 3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMatos, N. M. d. S., Sá, E. S. d., & Duarte, P. A. d. O. (2021). A review and extension of the flow experience concept: Insights and directions for tourism research. Tourism Management Perspectives, 38, 100802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A., Sousa, B., Santos, V., Ramos, P., & Madeira, A. (2023). Wine tourism and sustainability awareness: A consumer behavior perspective. Sustainability, 15(6), 5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S. K. (2021). Tourist consumption behavior: An unsolved puzzle. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 22(5), 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drennan, J., Bianchi, C., Cacho-Elizondo, S., Loureiro, S., Guibert, N., & Proud, W. (2015). Examining the role of wine brand love on brand loyalty: A multi-country comparison. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 49, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxbury, N., Bakas, F. E., Vinagre de Castro, T., & Silva, S. (2021). Creative tourism development models towards sustainable and regenerative tourism. Sustainability, 13(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza-Córdova, J. L., Bernardino-López, S., & Córdova Ruíz, Z. (2024). Estrategias de comunicación de las microcerveceras: La influencia de medios digitales en los consumidores de cerveza artesanal en Mexicali, Baja California, México. Hitos de Ciencias Económico-Administrativas, 30(86), 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, M., Moliner, M. Á., Monferrer, D., & Vidal, L. (2024). Sustainability and local food at tourist destinations: A study from the transformative perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 32(5), 1008–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eustice, C., McCole, D., & Rutty, M. (2019). The impact of different product messages on wine tourists’ willingness to pay: A non-hypothetical experiment. Tourism Management, 72, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felipe, C. M., Roldán, J. L., & Leal-Rodríguez, A. L. (2017). Impact of organizational culture values on organizational agility. Sustainability, 9(12), 2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerke, G. B. (2023). Gen Z and older Millennials dictate beverage direction: A new report from The Hartmann Group, called the “Modern Beverage Culture 2023,” offers valuable insights on consumer preferences, and how simple ingredients are winning the day. Beverage Industry, 95(11). Available online: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A780129817/AONE (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Gil Arroyo, C., Barbieri, C., Knollenberg, W., & Kline, C. (2023). Can craft beverages shape a destination’s image? A cognitive intervention to measure pisco-related resources on conative image. Tourism Management, 95, 104677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo Oliveros, M. E., Ortiz Velásquez, M., & Castro Abello, M. d. (2021). Marketing. Editorial Universidad del Norte. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, C., & García, M. (2020). Identidad local y consumo emergente de cerveza artesanal en México. Revista Mexicana de Estudios Socioculturales, 12(1), 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Carmona, D., Paramio, A., Cruces-Montes, S., Marín-Dueñas, P. P., Aguirre Montero, A., & Romero-Moreno, A. (2023). The effect of the wine tourism experience. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 29, 100793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Corona, C., Chollet, S., Escalona-Buendía, H. B., & Valentin, D. (2017). Measuring the drinking experience of beer in real context situations: The impact of affects, senses, and cognition. Food Quality and Preference, 60, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Gallo, S., & Hernández Zelaya, S. L. (2020). El olfato en el marketing sensorial: Estudio de caso de Zara Home. Redmarka Revista De Marketing Aplicado, 24(2), 201–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, P., Guenther, M., Ringle, C. M., Zaefarian, G., & Cartwright, S. (2023). Improving PLS-SEM use for business marketing research. Industrial Marketing Management, 111, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Tamez, C. R., & Franco-García, M. (2022). Influence of flow experience, perceived value and CSR in Craft beer consumer loyalty: A comparison between Mexico and The Netherlands. Sustainability, 14(13), 8202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Gudergan, S. P., Apraiz, J. C., Carrión, G. A. C., & Roldán, J. L. (2021). Manual avanzado de Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). OmniaScience Scholar. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Howard, M. C., & Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C. M., Johnson, G., Cambourne, B., Macionis, N., Mitchell, R., & Sharples, L. (2023). Wine tourism around the world: Development, management and markets (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. International Marketing Review, 33(3), 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J., Kwak, H. S., Kim, M., Kim, J.-H., Baek, H. H., Shin, H., Lee, Y.-s., Lee, S., & Kim, S. S. (2020). Major sensory attributes and volatile compounds of Korean rice liquor (yakju) affecting overall acceptance by young consumers. Foods, 9(6), 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, A. L., Alarcón, S., & Meraz Ruiz, L. (2022). Segmentation of wine tourism experience in Mexican wine regions using netnography. International Journal of Wine Business Research, 34(3), 427–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Mora, Y. N., Verde-Calvo, J. R., Malpica-Sánchez, F. P., & Escalona-Buendía, H. B. (2022). Consumer studies: Beyond acceptability—A case study with beer. Beverages, 8(4), 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannah, M. M., & Fadli, J. A. (2023). The effect of brand satisfaction and consumer experience on brand loyalty through brand love. International Journal of Social Health, 2(3), 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyanaram, G., & Winer, R. S. (2022). Behavioral response to price: Data-based insights and future research for retailing. Journal of Retailing, 98(1), 46–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E., Cunha, D., Eletxigerra, A., Carvalho, M., & Silva, I. (2022). The Experience Economy in a Wine Destination—Analysing Visitor Reviews. Sustainability, 14(15), 9308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N., & Lynn, G. S. (2012). Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 13(7), 546–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva-Hernández, S. N., Terán-Bustamante, A., & Martínez-Velasco, A. (2023). COVID-19, social identity, and socially responsible food consumption between generations. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1080097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva-Hernández, S. N., & Toledo-López, A. (2024). Motivators of the intention of wine tourism in Baja California, Mexico. Foods, 13(22), 3651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., & Cao, B. (2022). Study on tourism consumer behavior and countermeasures based on big data. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, 2022, 6120511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, J. a. W., & Arroyo, P. (2022). Prediction of the wine price purchased using classification trees. Vinculatégica EFAN, 8(6), 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Rosas, C. A., & Espinoza-Ortega, A. (2018). Understanding the motives of consumers of mezcal in Mexico. British Food Journal, 120(7), 1643–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J., & Smith, A. (2021). Events and sustainability: Why making events more sustainable is not enough. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(11–12), 1739–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marone, E., Bertocci, M., Boncinelli, F., & Marinelli, N. (2017). The cost of making wine: A Tuscan case study based on a full cost approach. Wine Economics and Policy, 6(2), 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meraz Ruiz, L., Olague De la Cruz, J. T., & & Ortega Pérez Tejada, M. (2022). Elementos que influyen en la decisión de compra de la cerveza artesanal de Tijuana, México. Criterio Libre, 19(35), 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moane, P., Galkin, V., & Solmi, A. (2020). A framework for generating loyalty in the alcohol industry: A case study of Heineken and Budweiser. In The strategic brand management: Master papers. Lund University Publications. Available online: https://lup.lub.lu.se/student-papers/search/publication/9031869 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Molleví, G., Nicolas-Sans, R., Álvarez, J., & Villoro, J. (2020). PDO certification: A brand identity for wine tourism. Geographicalia, 72, 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Aguilar, L. A., Guerrero-López, C. M., Colchero, M. A., Quezada-Sánchez, A. D., & Bautista-Arredondo, S. (2021). Elasticidad precio y elasticidad ingreso de la demanda de cerveza en México. Salud Pública de México, 63(4), 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Ortiz, R. (2025). La industria del vino tinto en México. El impacto económico de la Ruta del Vino Tinto en el Valle de Guadalupe. Revista UGC, 3(1), 139–146. Available online: https://universidadugc.edu.mx/ojs/index.php/rugc/article/view/82 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Murray, A., & Kline, C. (2015). Rural tourism and the craft beer experience: Factors influencing brand loyalty in rural North Carolina, USA. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(8–9), 1198–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzl, C. (2016). The use of partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) in management accounting research: Directions for future theory development. Journal of Accounting Literature, 37(1), 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, C. E. F. (2022). Alcances y estrategias del marketing relacional, una revisión sistemática de la literatura. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar, 6(3), 3926–3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H., Assaf, A. G., & Baloglu, S. (2014). Motivations and goals of slow tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 55(2), 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R. L. (2015). Satisfaction: A behavioral perspective on the consumer (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, E. D., & Ro, H. (2021). Generation Z and their perceptions of well-being in tourism. In N. Stylos, R. Rahimi, B. Okumus, & S. Williams (Eds.), Generation Z marketing and management in tourism and hospitality: The future of the industry (pp. 101–118). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortegón-Cortázar, L., & Rodríguez, A. G. (2017). Gestión del marketing sensorial sobre la experiencia del consumidor. Revista De Ciencias Sociales, 22(3), 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyinseye, P., Suárez, A., Saldaña, E., Fernández-Zurbano, P., Valentin, D., & Sáenz-Navajas, M. (2022). Multidimensional representation of wine drinking experience: Effects of the level of consumers’ expertise and involvement. Food Quality and Preference, 98, 104536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, M., & Loria, D. E. (2020). Macroeconomía. Versión para Latinoamérica (11th ed.). Pearson Educación. [Google Scholar]

- Perugini, M., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2001). The role of desires and anticipated emotions in goal-directed behaviours: Broadening and deepening the theory of planned behaviour. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(1), 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez Ricardo, E. C., Bastida Sánchez, E., Coronado Provance, K. Z., Medina Labrada, J. R., & Feria Velázquez, F. F. (2023). Predicción del comportamiento del consumidor en destinos turísticos. Investigaciones Turísticas, (26), 320–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (2019). The experience economy: Competing for customer time, attention, and money (rev. ed.). Harvard Business Review Press. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PROFECO. (2024). Revista del consumidor. Precios y características de la cerveza. Available online: https://bibliotecadelconsumidor.profeco.gob.mx/documento/68155aed350daaf0cb0cd24d (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Relph, E. (1976). Place and placelessness (Vol. 67). Pion. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G. (2021). Rethinking cultural tourism. Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, R. B. (2021). The role of tourism in sustainable development. In Oxford research encyclopedia of environmental science. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Mitchell, R., & Gudergan, S. P. (2020). Partial least squares structural equation modeling in HRM research. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(12), 1617–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V., Ramos, P., Almeida, N., & Santos-Pavón, E. (2020). Developing a wine experience scale: A new strategy to measure holistic behaviour of wine tourists. Sustainability, 12(19), 8055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Jr., Cheah, J. H., Becker, J. M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). How to specify, estimate, and validate higher-order constructs in PLS-SEM. Australasian Marketing Journal, 27(3), 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., Thiele, K. O., & Gudergan, S. P. (2016). Estimation issues with PLS and CBSEM: Where the bias lies! Journal of Business Research, 69(10), 3998–4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Hair, J. F. (2021). Partial least squares structural equation modeling. In Handbook of market research (pp. 587–632). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Sáenz-Navajas, M., Valentin, D., Gómez-Corona, C., & Rodrigues, H. (2024). Measuring wine and beer drinking experience in a context of limited socialisation: A case study with Spanish drinkers. OENO One, 58(1), 7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A. P. (2017). A flavour of emotions: Sensory & emotional profiling of wine, beer and non-alcoholic beer [Ph.D. thesis, Wageningen University]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza-Coutinho, M., Brasil, R., Souza, C., Sousa, P., & Malfeito-Ferreira, M. (2020). Consumers associate high-quality (fine) wines with complexity, persistence, and unpleasant emotional responses. Foods, 9(4), 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M. J. (2023). Beer traveler, wine traveler, or both? Comparing beer tourist and wine tourist segments. Tourism Analysis, 28(4), 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strub, L., Kurth, A., & Loose, S. M. (2021). Effects of viticultural mechanization on working time requirements and production costs. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture, 72(1), 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejo-Pech, C. O., Arellano-Sada, R., Coelho, A. M., & Weldon, R. N. (2012). Is the Baja California, Mexico, wine industry a cluster? American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 94(2), 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiakis, T., Anagnostou, E., Granata, G., & Manakou, V. (2022). Communicating terroir through wine label toponymy: Greek wineries practice. Sustainability, 14(23), 16067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiou, E., Agnoli, L., Charters, S., & Georgantzis, N. (2024). Feelings and alcohol consumption. Journal of Economic Psychology, 104, 102745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, A. L., Delhummeau, R. S., Castro, L. L. d. R., & De Lira, G. C. (2023). Retos de la industria vitivinícola de Baja California, México. BIO Web of Conferences, 56, 03015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinito Lindo, T. (2025). Vinos californianos. Available online: https://vinitolindo.com/collections/baja-california (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Wang, X., Frank, S., & Steinhaus, M. (2024). Molecular Insights into the Aroma Difference between Beer and Wine: A Meta-Analysis-Based Sensory Study Using Concentration Leveling Tests. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 72(40), 22250–22257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, D. F., & Gshayyish, A. M. (2024). Customer experience and role in behavioral intentions case study for customers of tourism organizations. American Journal of Social Sciences and Humanity Research, 4(8), 186–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A., López, B., & Martínez, C. (2020). Sensibilidad al precio y percepción de calidad en el turismo gastronómico mexicano. Revista Mexicana de Turismo y Gastronomía, 15(2), 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Yactayo-Moreno, A. G., & Vargas-Merino, J. A. (2021). Distinción conceptual y teórica de Marketing Sensorial: Tendencias y perspectivas. Investigación Y Ciencia De La Universidad Autónoma De Aguascalientes, 29(83), e2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z., Sun, S., Lalwani, A. K., & Janakiraman, N. (2019). How does consumers’ local or global identity influence Price–Perceived Quality associations? The role of Perceived quality variance. Journal of Marketing, 83(3), 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52(3), 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).