Abstract

The economic resources of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) follow a national diversification strategy that aims at sustainable growth. In this scenario, archaeological tourism plays a significant role in affirming cultural heritage but remains dependent on variables that are difficult to manipulate. This paper examines not only the opportunities but also the structural constraints of developing archaeology-based tourism propositions in a rapidly growing and highly competitive economy. The UAE counts on multiple sites, all of which face a combination of challenges to sustainable development. These comprise commercial tensions, environmental and infrastructural concerns, perspectives on authenticity, as well as global socioeconomic pressure. Such constraints are analyzed by tapping into the existing literature and recommendations for policymakers are offered in order to balance heritage conservation with economic growth. The findings emphasize the need for prioritizing community engagement and favoring sustainable representations of Emirati archaeology.

1. Introduction

This study seeks to explore the interplay between archaeological heritage, its effective or potential commodification, and identify the constraints in optimizing them in a specific tourism ecosystem. It does so by detecting recurring topics in the recent literature on the United Arab Emirates and aligning the results with the country’s cultural tourism configurations. The gap to be addressed does not directly stem from conditions related to archaeological research (Potts, 2012) or even museums and other outreach platforms, which have been conveniently deployed across the Emirates as part of a cultural diplomacy strategy (Antwi-Boateng & Alblooshi, 2025). Instead, attention is drawn to intrinsic and circumstantial barriers in the UAE tourism supply chain (De Man, 2024) affecting the sustainable commodification of sites and artifacts. Due to its uniqueness and public nature, which increase value, archaeological heritage cannot be freely fabricated and is therefore often marginalized in tourism propositions, which decreases price and consequently private interest. Territorial characteristics play a major part in a tourism venture and suppliers deal with tipping points in infrastructure, hence financial sustainability beyond which no heritage-based investment should be considered. Critical success factors in this sector are abundant (Gould & Burtenshaw, 2020) but two correlated hindrances should be highlighted: commercial formulas detrimental to perceived authenticity and a reduced appetite for archaeology-grounded business development, as discussed below.

Opportunities for sustainable growth do exist, though, in a careful reuse of certain archaeological remains (Mazzetto, 2023). The wide-ranging transformation of the UAE relies on an increasingly diversified economy, moving away from an almost exclusive oil dependency towards complex alternatives in the financial, real estate, and other service industries. Central to this ongoing strategy is travel and tourism development, which is projected to contribute 5.4% to the total GDP in 2027 and has been counting on yearly increases of 5.1% (Faraj et al., 2024). The intent has been to create a tourism cluster offering a national competitive advantage (Bouchra & Hassan, 2023), in line with a longstanding and empirically supported approach (Hatemi-Jarabad, 2016). A key pillar pervasive to all national and emirate-level sectorial plans (Papadopoulou, 2022) is cultural tourism and in particular the offerings based on archaeological tangibles from the ancient to the contemporary period (Power, 2024), ranging from fully commodified urban attractions to remote desert sites.

Based on this general outline, three vectors are examined in order to gain a nuanced view on widespread presumptions (Afkhami, 2021; Galluccio & Giambona, 2024; Gould, 2014) taking archaeological heritage as a catalyst for the advancement of quality leisure products. Firstly, the main secondary sources on the development of archaeological tourism in the UAE are identified. The study then employs a systematic approach to analyze the constraints for existing and potential archaeological tourist attractions in the UAE through the lens of spatial and thematic interplay. Lastly, recommendations for the preservation of sustainable cultural tourism are provided by taking into account the limits of archaeological resources.

2. Materials and Methods

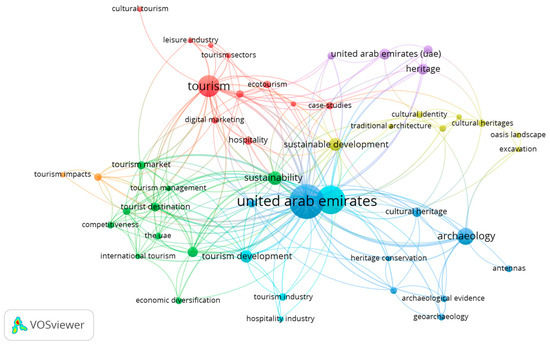

Leisure-centric forms of archaeology depend on preformatted activities, either on-site as part of a tourist itinerary or in some form of exhibition setting. As a result of the arid UAE climate and landscape, large cities favor retrofitted and architectural heritage tourism (Haq et al., 2021) while archaeological sites do provide a marketable cultural uniqueness but not necessarily a mainstream attractiveness. Still, quite some urban and extra-urban archaeological research has been carried out in the recent past (see, e.g., the last volume of the Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies; Karacic, 2023). Site commodification is, however, not a priority in academic research and, in the majority of cases, connections with the tourism industry are not automatic or feasible. The binary tension between research and leisure is rarely aligned in the literature on UAE archaeology. It does shine through in a number of scattered publications, which are hard to identify without computational support. Their mapping and clustering pin down several intersecting topics of concern in the recent literature without the need for enhanced bibliometric analyses or systematic literature reviews. The aim is to obtain reasonable categories at the macrolevel, that is, a bearing of central ideas rather than a comparative discussion on specific papers.

Retrieving information from academic databases is relatively straightforward but filtering for thematic relevance poses a number of conceptual challenges (Singh et al., 2023). Several approaches can be used without the need for coding skills (Caputo & Kargina, 2022; Nikolić et al., 2024), even for very large and complex datasets (Kasaraneni & Rosaline, 2024). For this paper, the Visualization of Similarities (VoS) technique (van Eck & Waltman, 2014) was used on Scopus data as it provides a proper visualization of network capillarity. A directly correlated matter is the theoretical framework underpinning this analysis. The tourism industry comes over as favorable to UAE residents, in particular, its economic consequences (Dutt et al., 2023). A specific alignment with archaeological tourism would postulate that stakeholders support investment in tourism and heritage as long as perceived benefits, most commonly economic ones, outweigh costs, for instance, cultural erosion due to overtourism or misrepresentation. UAE citizens and expat residents generically agree on the advantages of heritage tourism and are, precisely, more sensitive towards immediate economic impacts than to long-term cultural changes, which are difficult to perceive.

Constraints specific to UAE archaeological tourism are partly sociocultural, given the typical risks of commodification, especially the potential effect on authenticity and identity (cf. the notion of heritage rationalities in Bortolotto, 2021). This is a permanent concern to visitors, again to expats, and especially to Emirati nationals to whom hyper-modernization comes at the cost of rapid change in customs that may affect traditions, represented in a touristic shape and form (Sai Viswanathan & Miller, 2023). Indeed, tourism growth requires using the very heritage uniqueness it needs to transform for adequate mass consumption, which simultaneously ensures and destroys its sustainability. This paradox is arguably more acute in the UAE context because of the combination of very dynamic growth and the proportion of foreign residents whose presence instigates cultural change (Baycar, 2023). A similar conservational contradiction results from the fact that archaeological sites are highly vulnerable to all sorts of visitor pressure while these same tangibles are to ensure attraction in the first place (Salim et al., 2024). Infrastructural restrictions are also common and relate to geographical features in combination with access and ancillary services, on the one hand, and the physical expression of the touristified archaeological attraction, on the other. For these reasons, the positive domino effect (Aburumman, 2020) stimulated by other UAE tourism subsectors (MICE, medical, luxury) may not be equally perceptible in the archaeological tourism supply chain.

Given such a setting, this study follows a qualitative research design and adopts a systematic literature review (SLR) for synthesizing secondary data. Standard guidelines (Snyder, 2019; Xiao & Watson, 2019) were tailored to fit the primary research question: What are the limitations for archaeological and cultural heritage tourism in the UAE as identified in the literature? Secondary research questions address methodological, contextual, and theoretical factors. For conceptual clarity, these can be developed against a background framework on the development of tourism destinations, for instance, the life cycle model popularized, adapted, and revalidated by Butler (1980, 2024) and subsequent authors (Agarwal, 2002), despite the lack of full-cycle dynamics specifically based on UAE archaeological attractions—with the possible exception of the partial and isolated examples mentioned below. Other mainstream approaches such as the typologies used by McKercher and du Cros (2002) and multiple further outputs by both, as well as Social Exchange Theory applied to tourism (synopsis in Doğantekin, 2022), fit this supply-oriented paper less well because they heavily emphasize the nature of demand, that is, the motivation of visitors, which represents an alternative angle to be explored.

A data search was carried out by retrieving information from across the Scopus database to ensure peer-reviewed source material. Controlled vocabulary (e.g., keywords) and free text were scanned for publications within the time frame 2015–2025 to guarantee up-to-date perspectives on the challenges. The search terms used were “UAE”, “tourism”, “archaeology”, and “heritage”, using the key Boolean operators AND for UAE and OR for the others, thus refining the results, which were further enhanced by additional hand-searching of references. The first stage consisted of title and abstract screening, followed by a full review. Four exclusion criteria were used as follows: irrelevance to the topic; lack of quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method results; publication language other than English; and non-systematic publications such as editorials. This resulted in 392 valid papers with varying connecting strengths between the search terms (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

VoS results based on Scopus data retrieved on 16 June 2025.

Data were thematically treated and resulted in the establishment of four categories according to which the potential sustainability of UAE archaeological tourism can be assessed. The limitations are a linear result of this case-based specificity, which is a combination of unique locations and secondary data availability. A degree of subjectivity is to be considered, given the qualitative nature of the study. Also, publications in English are dominant but may exclude other relevant studies.

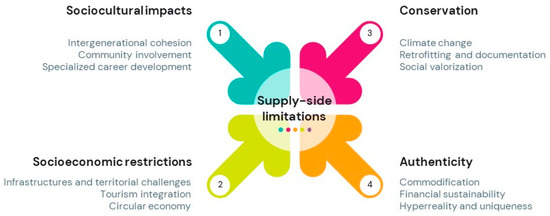

Several publications were included even if they do not strictly focus on the archaeology–tourism polarity but still address sustainable heritage in the UAE and were therefore considered relevant to the cultural ecosystem wherein archaeological tourism develops. The sheer number not just of known but also of potential archaeological sites in the UAE (Ben-Romdhane et al., 2023) represents in itself a limitation to long-term tourism integrations. Still, the intersections and articulations between clustered topics lead to a bracketing of the main concepts into four categories, respectively, sociocultural impacts (dominant keywords are sustainable development, tourism impacts, ecotourism, tourism and leisure industry, hospitality, digital marketing, and international tourism), socioeconomic restrictions (tourism market, management, and development, competitiveness, economic diversification, and tourist destination), conservation (archaeology, excavation, heritage conservation, archaeological evidence, and geoarchaeology), and authenticity (cultural identity, oasis landscape, cultural heritage, cultural identity, and traditional architecture). This represents both a simplification of concepts and a gradation between categories, given that each individual publication deals with specific topics, yet provides an overview of major trends in the recent literature, as indicated below.

3. Results

Against this backdrop, site profiles are used in a comparative analysis, taking into account the effectively commodified examples. The key evaluation criterion for archaeological tourism site selection is active promotion by all seven emirates’ Destination Management Organizations (DMOs), using AI tools for implementing sustainable marketing strategies (Jain, 2025). Conversely, the absence of governmental marketing and distribution implies no touristified archaeological product has been created, for which several reasons may exist. While the DMOs integrate the Emirates Tourism Council and as such may come over as theoretically equivalent players, namely in terms of promotional imagery, very large emirates are faced with more complex archaeological (i.e., tourism production) challenges. This causes spillover effects that interfere with the commercial usability of public history. Major cities successfully use both their urban area and their hinterland for Instagrammable heritage (Michael et al., 2025) while smaller emirates often have to construct new niche positionings in heritage hospitality and tourism (De Man, 2025). Based on the literature comprehensively analyzed above, it becomes clear that the limited diversity in cultural heritage suppliers and the logistical challenges for the effective integration of archaeological sites represent challenges to a smooth digital platformization. An overreliance on prefabricated online messages can distress not only the marketing efforts but also the pricing and distribution of archaeological leisure products. These and other supply-side limitations can be classified into four different categories (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Four categories of supply-side limitations.

3.1. Sociocultural Impacts

Most forms of local community life are susceptible to disruption by archaeological tourism. This may come in the form of overtourism, particularly harmful to emerging and small cultural destinations in the UAE and the Arabian Gulf (Gutberlet, 2023), affecting not only the physical conservation of a given site but also the population of the extended area. Increased traffic and movement may very well create opportunities for economic diversification but at the same time affect the daily habits of residents, most of which will have no direct vested interest in archaeology or tourism.

An additional factor to be considered is the diverse composition of the UAE population and the expat influx that creates challenges for the preservation of Emirati traditions. The resulting sociocultural fusion is certainly impacting local tourism development but internal generational gaps need to be considered in addition to the international factor (Zaidan et al., 2016). While archaeological sites cater to international tourism expectations and therefore acquire a transcultural purpose, they also serve as beacons of identity to UAE intergenerational cohesion. Supporting traditions attached to tangibles, sites, and cultural landscapes or living heritage (Bridi & De Man, 2025; Wakefield, 2022) mitigates the potential erosion of local community life.

Specialized functions in the cultural tourism industry, especially vocational roles such as tour guides, have traditionally not been widely occupied by UAE nationals (Rutledge, 2023) and the sector can only benefit from an increase in local human capital. On the other hand, survey results on domestic heritage tourism demonstrate clear awareness and interest originating from all emirates and demographics (Aldhanhani & Zainudin, 2022), and a comparatively lower sensitivity towards cultural and social impacts of UAE society than, for instance, economic ones (Hammad et al., 2017).

Different takes by UAE residents and tourists on several historical tangibles, namely integrated into densely populated cities (Awad et al., 2022), reinforce the notion of bottom-up requirements according to the precise meaning and configuration of a site. Moreover, their use as tourism attractions can be debated as the UAE population seems to make no clear distinction between many daily leisure activities and actual tourism (Slak Valek & Fotiadis, 2019).

3.2. Socioeconomic Restrictions

The UAE counts on highly developed national, emirate-level, and municipal tourism infrastructures (Bodolica et al., 2020) but not all archaeological sites are equally commodified and optimized for leisure. Visitor facilities, hospitality offerings, and road systems cannot be operated in remote areas where archaeology might be dimensioned only for niche activities such as trekking or allocentric desert experiences.

The substantial investment required to build, market, and operate interpretation centers is deployed only in cases of sustainable tourism integration. Tourism and heritage agencies in the UAE deal with unequal commercial landscapes and low revenue prospects in several inland centers where a lack of private investment reduces tourism dynamics (Al Dhaheri & Ahmad, 2019), notwithstanding the importance of local archaeological remains. Even where limited profits are not expected to compensate for public investment in culture, site development can be further hindered by a lack of permanent qualified staff available to work in isolated locations, regardless of the infrastructure.

Imbalances between tourist expectations and effective archaeological tangibles may also reduce stakeholder enthusiasm regarding the construction of infrastructures. One way forward is to increase forms of the circular economy not only in the UAE hospitality industry but especially in community-based heritage tourism (Issac, 2025). A large number of UAE attractions refer to late modern and contemporary archaeology, for instance, the set of forts across all emirates, reinvented as exhibition and cultural spaces (Ataya & Page, 2022). Some other historical buildings have similarly been retrofitted into multipurpose spaces (Barucco et al., 2024). Some major island sites along the UAE coast are currently not accessible for tourism development due to legal and other practical limitations (e.g., Siniya; see Power et al., 2024), while others have been fully integrated with hotel and leisure infrastructures, as is the case of Sir Bani Yas (Goodburn-Brown et al., 2017; Lic et al., 2023).

3.3. Conservation

Archaeological sites are vulnerable attractions and continuously suffer from anthropic and environmental impacts. Even if the former can be reasonably contained through the enforcement of legislation and responsible tourism practices, the UAE climate potentiates accelerated degradation due to extreme heat and other related particularities such as sand movements and flash floods, which are not expected to decrease in the foreseeable future. Climate change is indeed a threat to long-term UAE site sustainability and risk reduction maps have been created (Yagoub & Al Yammahi, 2022) as instruments for measuring and mitigating the future destruction of heritage. Urban development has led to the integration of historical tangibles into contemporary layouts and this often involves retrofitting and conservation for daily use (Assi, 2024; Salameh & Touqan, 2023; Trusiani & D’Onofrio, 2024) but also the enclosure of archeological features within residential neighborhoods (De Man & Hassan, 2023).

National and emirate-level tourism strategies include the preservation of heritage attractions, as well as the perceptions of group identity. This needs to be seen in the scope of policymaking procedures by using proper indicators (Raevskikh et al., 2024) and places built for cultural interpretation. Indeed, museums function as custodians of archaeological features and, in addition to their physical conservation and exhibition, ensure the interpretation of representative objects, often assuming a biographical purpose as well (Shakour, 2019). Similarly, archaeological and other heritage resources require documentation and subsequent archival preservation, which is part of the UAE library strategy (Kaluvilla, 2024). Documenting archaeological structures and objects is another vector that intersects between field research, conservation, and exhibition (Holden et al., 2015).

3.4. Authenticity

A key challenge to the financial sustainability of archaeological tourism remains its entrepreneurial dimension. The commodification of public heritage creates pressures impossible to reconcile with radical historical truth as the consumer seeks a simplified leisure experience. The setup of a balanced perception of authenticity affects different segments of visitors in UAE heritage operations (Alazaizeh et al., 2024). Staged exhibition displays and monetized offerings by players such as tour operators and souvenir shops can undermine the expectations of tourists, heritage experts, and local communities. Some authors claim that the packaging of UAE heritage has been “Westernized” for tourism (Thani & Heenan, 2020). This sort of analysis feeds into a currently popular discussion on decolonizing culture worldwide but admittedly there is a threshold beyond which the cosmopolitanism of large metropoles, including Sharjah, Dubai, or Abu Dhabi, may become an obstacle to ethnographic tourism. One way of processing this in the case of the UAE is through a participatory heritage discourse (Rizvi, 2018) allowing for balanced leisure propositions.

Despite its increasing potential, namely in determining country-wide and comparative visitor satisfaction (Abou-Shouk et al., 2024), artificial intelligence may impact UAE cultural heritage integrity (Hassouni & Mellor, 2025). This directly relates to widely used technological interfaces and the positive results of apps in the organization of UAE heritage initiatives (Hossain et al., 2022) depend on the quality of upstream data as much as strict consumer-centered aspects such as readability and authenticity. The UAE economy diversification goals have yielded the broadening of source markets and main hubs such as Dubai and Abu Dhabi have become conventional destinations. In this dynamic scenario, UAE cultural tourism can sometimes be seen as a fabricated hyperreality competing with luxury segments (Sai Viswanathan & Miller, 2023) but the aim is to generate complementarities between heritage and leisure, a common aim across the region. Despite the state-specific singularities in the tourism of the Gulf countries (Stephenson & Al-Hamarneh, 2017), they all anchor their marketable identity on a mix of similarities and unique historical tangibles, among which archaeology is an explicit generator for development (Al-Belushi, 2015). Indeed, regional destinations are increasingly competing for market share and archaeological heritage attractions such as AlUla in Saudi Arabia (Filippi & Mazzetto, 2024) or Al Zubarah in Qatar (Campbell, 2022) provide luxury hotel options in combination with nearby archaeological and landscape uniqueness. In such a contending tourism environment, UAE brand equity is purposefully based on cultural heritage uniqueness and authenticity (Haq et al., 2021; Kumail et al., 2021).

4. Discussion

The screening of the seven DMOs’ online presence, including their institutional and promotional outreach platforms (Kumail et al., 2021), highlights multiple sites as attractions. Many of these are not immediately reachable by the occasional day-tripper and may require some elementary off-roading or trekking preparation. The UAE’s geodiversity offers attractive tourism propositions (Allan, 2023) to which archaeology can add cultural density but at the same time reduces commercial scaling. In the case of the Abu Dhabi Department of Culture and Tourism (DCT), three locations are singled out in the Al Ain region: Bida bint Saud, Jebel Hafeet, and Hili. They are components of a UNESCO World Heritage serial property that includes oases areas with multiple other archaeological, albeit not standalone elements in visitable settings (Power & Sheehan, 2011; Zeidan, 2023). While the tombs at Bida bint Saud (Magee, 2007) are accessible and have minimal signage, they lack complex ancillary structures and their materials are on display elsewhere. The Jebel Hafeet Desert Park offers camping facilities and is promoted as an opportunity to visit the local archaeological site (Madsen, 2018) at an only marginally commodified mountain location. Hili, in turn, is a public park built around a conserved archaeological attraction yet within a larger buffer zone containing several other, less easily accessible remains (McSweeney et al., 2010). At a large distance from Al Ain and Abu Dhabi city, Ghagha island is the other archaeological site promoted by DCT on the visitabudhabi.ae website, although currently with limited general public access, as is the case with most islands along the Abu Dhabi coast. One tourism-oriented exception is Sir Bani Yas Island (Reitsma & Little, 2021), where hotel and bungalow facilities do exist in adjacency to an archaeological site with an interpretation center.

Dubai counts on archaeological resources with different tourism integrations. If important sites such as Al Sufouh (Benton et al., 1996) and Al Qusais (Contreras et al., 2025) lay within urban plots, publicly visible from the roads and well-protected from any real estate expansion, they are not visitable as fully developed leisure attractions. In a completely separate geographical setting, the complex desert site of Saruq al-Hadid (Weeks et al., 2024) is equally not open for tourist consumption but the corresponding materials are on display in the city. A third sort of development can be experienced at the Jumeirah Archaeological site (Juchniewicz & Lic, 2023), amidst a low-raise residential area with the iconic Business Bay and Burj Khalifa cityscape in the background. Here, both the excavated structures and representative materials exhibited at an interpretation center can be visited, with a traditional teahouse adding an everyday F&B appeal to the site.

The emirate of Sharjah extends to both coasts, from the Arabian Gulf to the Sea of Oman. The variety of historical landscapes is reflected by academically renowned, albeit not easily visitable sites and a corresponding archaeological museum with finds from Tell Abraq and other sites such as Kalba and Mleiha (Overlaet et al., 2023). The latter is located in a low-density area, even though it is well connected by road to the wider region. Its interpretation center integrates the Mleiha National Park, where the original archaeological attraction has been complemented by organized tourism activities such as glamping and stargazing, sand surfing, or buggy rides. The other northern emirates do count on a variety of archaeological sites and promote them in permanent exhibitions. Historical and architectural tangibles suggested by the DMOs may be used in constructing tourism itineraries and archaeological heritage is occasionally included (De Man, 2025).

Among the well over one hundred archaeological and paleoenvironmental sites in the UAE (Sayama et al., 2022), a mere handful have been fully integrated into the tourism supply chain and dedicated infrastructures as well as site museums are therefore the exception. Each emirate does count on permanent displays of archaeological materials, often in retrofitted forts used as cultural spaces, and sometimes in an assortment with ethnographic collections. As elsewhere, the conservation, tourism usefulness, and daily management of a site need to make cultural and economic sense to communities. While in theory any type of remain can be suitably commodified through immersive, interactive, and branded experiences, the practicalities of doing so for each individual UAE site come over as unreasonable, as the added value would dissipate.

Deterrents for the development of archaeological site tourism are a combination of the following factors. They synthesize theoretical contributions concerning a research gap on the limits of sustainability, followed by practical recommendations.

- -

- Perceived market overlaps due to the impression of repetitiveness and lack of uniqueness are incompatible with successful tourism integration. Many archaeological sites may appear as offering equivalent experiences; hence, their attractiveness becomes reduced in what is an already saturated market. This can partly be ascribed to inadequate interpretive branding strategies, given the intrinsic uniqueness of all single sites. Ways forward can include differentiated visitor segmentation and more personalized forms of communication such as digital interactivity or storytelling.

- -

- Return on investment (ROI) for private stakeholders, once public monies might have ensured basic functions such as research and conservation, poses a second major challenge. The economic viability of touristified sites is indeed a serious entrepreneurial challenge as downstream efforts by hospitality and tour operators seek to prioritize ROI in a non-intensive sector that, however, depends on high investment and permanent labor costs. Critical production factors, namely the academic and other public requirements of archaeological resources, cannot be controlled by private investors who are necessarily reduced to freeriders and therefore tend to prefer more vertically articulated investments.

- -

- Geographical constraints represent logical impediments to developing archaeological site tourism. Most identified sites in the UAE are located not in the proximity of urban tourism hubs but instead in remote areas where their appeal is brandable but their visitability is marginal. The cost for private or even public players to invest in isolated sites based exclusively on archaeological tangibles is a deterrent in itself, especially as very few sites yield any monumentality, in which case there is no need for radical location-specific authenticity. If there is high tourism potential, transportation networks can be optimized to gain site access in a reasonably tourist-friendly manner, or virtual alternatives may be deployed for non-visitable sites. Inter-emirate planning is also an option for integrated archaeological itineraries.

- -

- Lastly, the physical nature and condition of the archaeological site remains a primary element of tourism interest. Underwhelming structures and physical surroundings can be of major importance to the advancement of archaeological research but will fail to impress visitors, who carry preconceptions about the impactful nature of sites. Tour operators have little interest in adding predictably disappointing elements to their products. Ways forward can consider AI-based interactive solutions and multilingual storytelling, in addition to a selective strategic undertaking where only a few selected sites are to be developed for conventional tourism.

5. Conclusions

Archaeological tourism represents a specialized component of a cultural leisure mix aimed simultaneously at visitors, expat residents, and national citizens. It offers considerable potential within the national diversification strategy but faces constraints affecting its sustainable development. They can be clustered as indicated above, by looking separately at sociocultural tensions, economic and infrastructural limitations, conservation reasons, and the correlated elements affecting perceived authenticity. By handling the four dimensions pointed out in this study, the UAE can tackle the resulting challenges and adopt sustainable strategies for archaeological tourism. This represents a comparable and transferrable exercise, as these insights may be applied to other economic propositions, both in the Arabian context and beyond. The reality on the ground will determine the optimal procedures, given the variety in the size and nature of urban and remote sites, and this necessarily connects with the specific emirate. Overarching solutions need to remain inclusive and authentic for successful tourism sustainability.

The standard suggestion in this sort of study is for policymakers to involve local communities in the process of creating and operating archaeological tourism attractions. Authenticity is thus ensured, as is the reasonable spreading of benefits across society. From an academic angle, sites may be managed as standalone research initiatives but, in terms of cultural tourism, global best practices indicate the advantages of public and private stakeholder integration. While entrepreneurial energy is essential, the public nature of the sites, in addition to transport networks and other ancillary background services in education, healthcare, and safety, requires government-driven frameworks for private players to thrive. Part of these responsibilities is guaranteeing smart tourism destination management based on accountable commitments towards heritage sustainability.

Hindrances to archaeological tourism in the UAE require interconnected solutions that focus on public–private partnerships coming over as viable to entrepreneurial players. The financial burden and the legal obligations of managing a public resource as is the case with archaeological heritage require some sort of incentive to the private sector—unless the entire endeavor is to dismiss any non-governmental initiative, which would exclude local communities and is therefore contrary to success. On the other hand, archaeological practice may be outsourced to some extent but cannot be fully privatized as it remains a public concern and assets need to be responsibly monetized.

Limitations inherent to this study include the use of the English-language literature during data acquisition, as well as possible subjectivity in the coding process. Also, the geographical specificity of the UAE is not automatically transferrable but can become comparable, hence useful for reviewing diverse contexts. Future studies may focus on longitudinal research on consumer behavior and environmental impact in order to more conveniently support evidence-driven public policy. Such studies require the identification of both qualitative and quantitative factors on motivation, decision-making, and resulting cultural patterns through the deployment of surveys and, increasingly so, the support of big data processing.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available at scopus.com. VOSviewer Online version 1.2.4, a software for constructing and visualizing bibliometric networks, is free to use for any purpose, including academic research and teaching.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abou-Shouk, M., Zouair, N., Abdelhakim, A., Roshdy, H., & Abdel-Jalil, M. (2024). The effect of immersive technologies on tourist satisfaction and loyalty: The mediating role of customer engagement and customer perceived value. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 36(11), 3587–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburumman, A. A. (2020). COVID-19 impact and survival strategy in business tourism market: The example of the UAE MICE industry. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 7(1), 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afkhami, B. (2021). Archaeological tourism: Characteristics and functions. Journal of Historical Archaeology & Anthropological Sciences, 6(2), 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S. (2002). Restructuring seaside tourism: The resort life-cycle. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(1), 25–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazaizeh, M. M., Mura, P., & Jamaliah, M. M. (2024). How are value orientations toward intangible cultural heritage important to local cultural festival development? Journal of Heritage Tourism, 20(3), 450–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Belushi, M. A. K. (2015). Archaeology and development in the GCC states. Journal of Arabian Studies, 5(1), 37–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Dhaheri, M. H., & Ahmad, S. Z. (2019). Department of tourism and culture—Abu Dhabi: Transforming the desert into a city. Emerald Emerging Markets Case Studies, 9(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhanhani, H. M. O. R., & Zainudin, M. Z. (2022). Willingness of residents to participate in UAE heritage and culture tourism industry. International Journal of Sustainable Construction Engineering and Technology, 13(4), 134–143. [Google Scholar]

- Allan, M. (2023). Geotourism in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). In M. Allan, & R. Dowling (Eds.), Geotourism in the Middle East (pp. 263–271). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi-Boateng, O., & Alblooshi, N. H. A. (2025). United Arab Emirates’ pursuit of soft power through cultural diplomacy and its challenges. Perspectives on Global Development and Technology, 24(3–4), 514–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assi, E. (2024). Impact assessment of urban heritage sites: The case of Khor Dubai, UAE. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment, 263, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataya, M., & Page, H. (2022). Heritage and community involvement: The case of Sharjah Fort (Al Hisn) museum. In A. Badran, S. Abu-Khafajah, & S. Elliott (Eds.), Community heritage in the Arab region (pp. 105–122). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, J., Arar, M., Jung, C., & Boudiaf, B. (2022). The comparative analysis for the new approach to three tourism-oriented heritage districts in the United Arab Emirates. Heritage, 5(3), 2464–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barucco, P., Chabbi, A., & Mordanova, A. (2024). Bait Mohammed Bin Khalifa, the challenging consolidation of an Emirati “transition period” building. In Y. Endo, & T. Hanazato (Eds.), Structural analysis of historical constructions (Vol. 47, pp. 873–884). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baycar, H. (2023). Promoting multiculturalism and tolerance: Expanding the meaning of “unity through diversity” in the United Arab Emirates. Digest of Middle East Studies, 32(1), 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Romdhane, H., Francis, D., Cherif, C., Pavlopoulos, K., Ghedira, H., & Griffiths, S. (2023). Detecting and predicting archaeological sites using remote sensing and machine learning—Application to the Saruq Al-Hadid site, Dubai, UAE. Geosciences, 13(6), 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, J. N., Benton, J. N., & Qandil, H. (1996). Excavations at Al Sufouh: A third millennium site in the Emirate of Dubai. Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Bodolica, V., Spraggon, M., & Saleh, N. (2020). Innovative leadership in leisure and entertainment industry: The case of the UAE as a global tourism hub. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management, 13(2), 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolotto, C. (2021). Commercialization without over-commercialization: Normative conundrums across heritage rationalities. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 27(9), 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchra, N. H., & Hassan, R. S. (2023). Application of Porter’s diamond model: A case study of tourism cluster in UAE. In R. El Ebrashi, H. Hattab, R. S. Hassan, & N. H. Bouchra (Eds.), Industry clusters and innovation in the Arab world (pp. 129–156). Emerald Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridi, R. M., & De Man, A. (2025). From heritage to high-tech: The impact of technology on camels in the United Arab Emirates. Heritage, 8(5), 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. (1980). The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution and implications for management of resources. The Canadian Geographer, 24(1), 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. (2024). Tourism destination development: The tourism area life cycle model. Tourism Geographies, 27(3–4), 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K. (2022). Presenting Al Zubarah archaeological site. In H. Al-Thani, N. Abdulla, S. Muhesen, A. Walmsley, F. Hassan al-Sulaiti, S. Rosendahl, & I. Thuesen (Eds.), Al Zubarah: Qatar’s world heritage city (pp. 195–206). Qatar University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caputo, A., & Kargina, M. (2022). A user-friendly method to merge Scopus and Web of Science data during bibliometric analysis. Journal of Marketing Analytics, 10(1), 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, F., Alonso, A., Fernández-Sánchez, A., Al Ali, B. M., Boraik, M., Zein, H., & Al Masfari, M. A. (2025). Proposed chronology of burial activity by period in the necropolis of Al-Qusais (Dubai, UAE). Annals of Archaeology, 7(1), 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Man, A. (2024). Positioning UAE archaeological sites in tourism supply chains. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Man, A. (2025). Hospitality and heritage tourism production in the Northern Emirates. In R. A. Castanho, T. Pivac, & A. Mandić (Eds.), Legacy and innovation (pp. 185–190). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Man, A., & Hassan, B. (2023). Notes on UAE heritage clustering for urban planning. AIP Conference Proceedings, 2881(1), 040001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğantekin, A. (2022). Social exchange theory and tourism. In D. Gursoy, & R. Nunkoo (Eds.), Routledge handbook of social psychology of tourism (pp. 61–67). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dutt, C. S., Harvey, W. S., & Shaw, G. (2023). Exploring the relevance of social exchange theory in the Middle East: A case study of tourism in Dubai, UAE. International Journal of Tourism Research, 25(2), 198–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraj, N., Alqaryuti, A., Mayyas, A., & Maalouf, M. (2024, November 4–6). A regression-based approach to explore tourism and hospitality trends in the UAE hotel sector. 2024 IEEE International Conference on Technology Management, Operations and Decisions (ICTMOD) (pp. 1–6), Sharjah, United Arab Emirates. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, L. D., & Mazzetto, S. (2024). Comparing AlUla and The Red Sea Saudi Arabia’s giga projects on tourism towards a sustainable change in destination development. Sustainability, 16(5), 2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluccio, C., & Giambona, F. (2024). Cultural heritage and economic development: Measuring sustainability over time. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 95, 101998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodburn-Brown, D., Norman, K., Elders, J., & Popescu, E. (2017). Preservation in situ for tourism: An early Christian monastic complex on Sir Bani Yas Island, Western Abu Dhabi, UAE. In Preserving archaeological remains in situ (pp. 252–265). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, P. G. (2014). Putting the past to work: Archaeology, community and economic development [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University College London]. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, P. G., & Burtenshaw, P. (2020). Heritage sites: Economic incentives, impacts, and commercialization. In C. Smith (Ed.), Encyclopedia of global archaeology (pp. 4989–4995). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutberlet, M. (2023). Overtourism and cruise tourism in emerging destinations on the Arabian Peninsula. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hammad, N., Ahmad, S. Z., & Papastathopoulos, A. (2017). Residents’ perceptions of the impact of tourism in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 11(4), 551–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, F., Seraphim, J., & Medhekar, A. (2021). Branding heritage tourism in Dubai: A qualitative study. Advances in Hospitality and Tourism Research, 9(2), 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassouni, A., & Mellor, N. (2025). AI in the United Arab Emirates’ media sector: Balancing efficiency and cultural integrity. Journalism and Media, 6(1), 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatemi-Jarabad, A. (2016). On the tourism-led growth hypothesis in the UAE: A bootstrap approach with leveraged adjustments. Applied Economics Letters, 23(6), 424–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, L. D., Silcock, D. M., Arrowsmith, C. A., & Al Hassani, M. (2015). Laser scanning for the documentation and management of heritage sites within the Emirate of Fujairah, United Arab Emirates. Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy, 26(1), 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S. F. A., Ahsan, F. T., Nadi, A. H., Ahmed, M., & Neyamah, H. (2022). Exploring the role of technology application in tourism events, festivals and fairs in the United Arab Emirates: Strategies in the post pandemic period. In A. Hassan (Ed.), Technology application in tourism fairs, festivals and events in Asia (pp. 305–322). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issac, A. L. (2025). Circular economy in tourism: Unlocking sustainable development opportunities in the UAE. In P. K. Tyagi, V. Nadda, & A. K. Singh (Eds.), Meaningful tourism (building the future of tourism) (pp. 221–237). Emerald Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R. (2025). Integrating artificial intelligence for smart destination management in the UAE: Opportunities, challenges, and impacts. In B. Varghese, & H. Sandhya (Eds.), Advancing smart tourism through analytics (pp. 245–260). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juchniewicz, K., & Lic, A. (2023). Abbasid Jumeirah, Dubai: An overview of the site and its architectural stucco decoration. Études et Travaux, 36, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaluvilla, B. B. (2024). Cultural preservation through technology in UAE libraries. Library Hi Tech News, 41(8), 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karacic, S. (Ed.). (2023). Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies: Vol. 52. Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Kasaraneni, H., & Rosaline, S. (2024). Automatic merging of Scopus and Web of Science data for simplified and effective bibliometric analysis. Annals of Data Science, 11(3), 785–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumail, T., Qeed, M. A. A., Aburumman, A., Abbas, S. M., & Sadiq, F. (2021). How destination brand equity and destination brand authenticity influence destination visit intention: Evidence from the United Arab Emirates. Journal of Promotion Management, 28(3), 332–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lic, A., Lichtenberger, A., Daher, R. F., & Zureikat, R. (2023). A note on the architectural layout of the early Islamic church on Sir Bani Yas Island, UAE. Études et Travaux, 36, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, B. (2018). The early Bronze Age tombs of Jebel Hafit: Danish archaeological investigations in Abu Dhabi 1961–1971 (Vol. 93). Universitetsforlag. [Google Scholar]

- Magee, P. (2007). Beyond the desert and the sown: Settlement intensification in late prehistoric Southeastern Arabia. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, 347(1), 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetto, S. (2023). Heritage conservation and reuses to promote sustainable growth. Materials Today: Proceedings, 85, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B., & du Cros, H. (2002). Cultural tourism: The partnership between tourism and cultural heritage management. The Haworth Press. [Google Scholar]

- McSweeney, K., Méry, S., & al Tikriti, W. Y. (2010). Life and death in an early Bronze Age community from Hili, Al Ain, UAE. In L. Weeks (Ed.), Death and burial in Arabia and beyond: Multidisciplinary perspectives (pp. 45–53). Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, N., Chunawala, M. A., & Fusté-Forné, F. (2025). Instagrammable destinations: The use of photographs in digital tourism marketing in the United Arab Emirates. Journal of Tourism, Heritage & Services Marketing, 11(1), 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, D., Ivanović, D., & Ivanović, L. (2024). An open-source tool for merging data from multiple citation databases. Scientometrics, 129(7), 4573–4595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overlaet, B., Jasim, S., & Yousif, E. (2023). Imported and local cylinder seals in the Oman Peninsula: Finds from Kalba, Tell Abraq and Mleiha (Sharjah Emirate, U.A.E.). Annual Sharjah Archaeology, 21, 8–22. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulou, G. (2022). The economic development of tourism in the United Arab Emirates. In S. Sindakis, & S. Aggarwal (Eds.), Entrepreneurial rise in the Middle East and North Africa: The influence of quadruple helix on technological innovation (pp. 111–123). Emerald Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, D. T. (2012). In the land of the Emirates: The archaeology and history of the UAE. Trident Press. [Google Scholar]

- Power, T. (2024). Human–environment interactions in the United Arab Emirates: An archaeological perspective. In J. A. Burt (Ed.), A natural history of the Emirates (pp. 315–339). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, T., Degli Esposti, M., Hoyland, R., Kannouma, R. H., Borgi, F., Iwaszczuk, U., Maini, E., Nicolosi, T., & Priestman, S. (2024). Excavations at a late antique to early Islamic pearling town and monastery on Sīnīya Island, Umm al Quwain. Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, 53, 211–229. [Google Scholar]

- Power, T., & Sheehan, P. (2011). Bayt Bin ʿĀtī in the Qaṭṭārah oasis: A prehistoric industrial site and the formation of the oasis landscape of al-ʿAin, UAE. Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, 41, 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- Raevskikh, E., Di Mauro, G., & Jaffré, M. (2024). From living heritage values to value-based policymaking: Exploring new indicators for Abu Dhabi’s sustainable development. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitsma, G., & Little, S. E. (2021). Case C: Creating desert islands–Abu Dhabi. In G. Go, & H. L. Gammel (Eds.), International place branding yearbook 2010: Place branding in the new age of innovation (pp. 77–87). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi, U. Z. (2018). Critical heritage and participatory discourse in the UAE. Design and Culture, 10(1), 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutledge, E. J. (2023). The tour guide role in the United Arab Emirates: Emiratisation, satisfaction and retention. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 23(4), 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sai Viswanathan, H., & Miller, M. L. (2023). Tourist, local, and broker perceptions of Abu Dhabi and Dubai, United Arab Emirates: Tourist gazes, ultra-artifacts, and hyperreality. The Arab World Geographer, 26(2), 142–179. [Google Scholar]

- Salameh, M., & Touqan, B. (2023). From heritage to sustainability: The future of the past in the hot arid climate of the UAE. Buildings, 13(2), 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, J., Sujood, Mishra, S., & Yasmeen, N. (2024). Archaeotourism unveiled: A systematic literature review and chronicles of built heritage conservation. Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, 26(2–3), 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayama, K., Parker, A. G., Parton, A., & Viles, H. (2022). Developing a geocultural database of Quaternary palaeoenvironmental sites and archaeological sites in Southeast Arabia: Inventory, endangerment assessment, and a roadmap for conservation. Sustainability, 14(21), 14096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakour, S. (2019). The role of contemporary biographical museums in heritage conservation in the UAE. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology, 28(16), 1695–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P., Singh, V. K., & Piryani, R. (2023). Scholarly article retrieval from Web of Science, Scopus and Dimensions: A comparative analysis of retrieval quality. Journal of Information Science. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slak Valek, N., & Fotiadis, A. (2019). Is tourism really an escape from everyday life? Everyday leisure activities vs leisure travel activities of expats and Emirati nationals living in the UAE. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 12(2), 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, M. L., & Al-Hamarneh, A. (2017). International tourism development and the Gulf Cooperation Council states. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thani, S., & Heenan, T. (2020). Theme park Arabism: Disneyfying the UAE’s heritage for western tourist consumption. In M. L. Stephenson (Ed.), Cultural and heritage tourism in the Middle East and North Africa (pp. 157–169). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Trusiani, E., & D’Onofrio, R. (2024). Urban guidelines and strategic plan for a UNESCO world heritage candidate site: The historical centre of Sharjah (UAE). Sustainability, 16(17), 7461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2014). Visualizing bibliometric networks. In Y. Ding, R. Rousseau, & D. Wolfram (Eds.), Measuring scholarly impact (pp. 285–320). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, S. (2022). The making of a heritage sport: Falconry in the UAE. In H. Jarvie (Ed.), Routledge handbook of sport in the Middle East (pp. 74–84). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks, L., Valente, T., Franke, K., Contreras, F., Radwan, M. B., & Zein, H. (2024). Iron Age copper production and the “ritual economy” of Saruq al-Hadid (Dubai, UAE). In Advances in UAE archaeology—Proceedings of Abu Dhabi’s archaeology conference 2022 (pp. 239–269). Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y., & Watson, M. (2019). Guidance on conducting a systematic literature review. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 39(1), 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagoub, M. M., & Al Yammahi, A. A. (2022). Spatial distribution of natural hazards and their proximity to heritage sites: Case of the United Arab Emirates. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 71, 102827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidan, E., Taillon, J., & Lee, S. (2016). Societal implications of UAE tourism development. Anatolia, 27(4), 543–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, H. (2023). Visitor management plan for the complex of Al-Ain national museum and the Eastern Fort (world heritage site). International Journal of Eco-Cultural Tourism, Hospitality Planning and Development, 6(1), 30–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).