1. Introduction

Ecotourism, broadly speaking, is environmentally sound travel to natural attractions in a manner that maintains the integrity of the environment and benefits local communities, and has become a central policy instrument for developing tourism sustainability (

Al-Amoudi, 2018;

Ismail et al., 2021). As global concern about climate change, biodiversity loss, and environmental degradation grows, ecotourism presents an attractive vehicle for promoting awareness, knowledge, and action towards pro-environmental behavior. In addition to its economic and conservation value, ecotourism is also of great interest due to its potential to cause psychological and emotional changes among tourists, which can have long-term effects on attitudes and behaviors toward the environment (

Ágoston et al., 2022;

Ballantyne & Packer, 2005;

Duong et al., 2022).

Even under such pledges of change, empirical evidence on ecotourism’s effects on sustainable behavior is mixed (

Carvache-Franco et al., 2021;

Gao et al., 2023). While vast tourist majorities report increased environmental awareness through or shortly after the ecotourism experience, the degree to which such experience actually finds expression in material post-visit behavior, such as environmentalism, philanthropy, or change in lifestyle, is still undecided. This well-documented intention–behavior gap is an important standard for tourism and environmental psychology (

Carvache-Franco et al., 2021;

Gao et al., 2023). Tourists might intend to behave in a sustainable manner but not do so when they go back to their everyday conditions, where social norms and other claims compete with pro-environmental intention (

Hassan et al., 2021;

Lee & Jan, 2018). Therefore, it is necessary to learn about the processes that facilitate or constrain this switch from intention to behavior.

Several theoretical models have attempted to account for pro-environmental action, the most popular of which is the value–belief–norm (VBN) theory (

Rafiq et al., 2022;

Rosmadi et al., 2024). VBN theorizes a chain from values to awareness of consequences to ascription of responsibility to Personal Norms that affect behavior. Extending VBN, the Experience Economy view contends that richly memorable, affect-laden experiences can alter later choice. In environmental psychology, awe and nature connectedness are associated with self-transcendence and moral elevation, which can increase personal commitment to act (

Sorcaru et al., 2025;

Ting et al., 2025). However, few ecotourism studies have combined these views to study how values before the visit, experiential quality at place, and emotional responses interact to build post-visit behavior.

In addition, whereas concepts like environmental concern, satisfaction, and trip quality have each been linked to tourist behavior, they are seldom combined into an integrated model that captures both the experiential and psychological routes to sustainable action after the trip (

L. Wang et al., 2025;

Wu et al., 2024). Notably, ASE—awe, wonder, and sense of felt connection with nature—is not extensively examined as an activator of PN elicitation and resultant behavior in tourism. We position ASE particularly as an affective cue that can enhance PN through self-downward comparison and moral salience, complementing more cognitive pathways through EC and PTQ (

Duong et al., 2022;

Ismail et al., 2021). Such an under-study emphasizes the necessity for a more convergent model that considers how levels of experience and psychology intersect to affect responsible post-visit behavior (RPB).

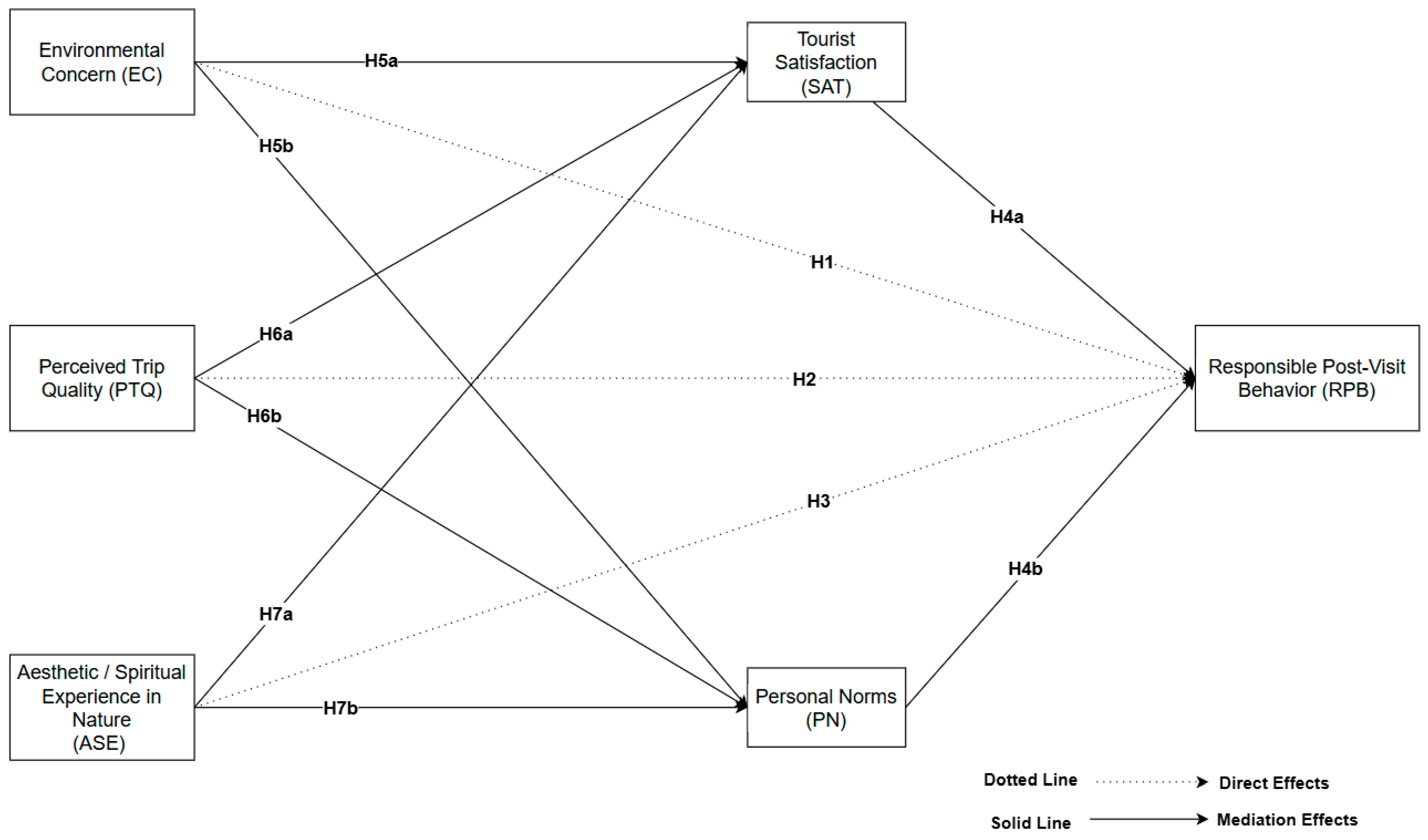

In spite of extensive investigation into learning and satisfaction in ecotourism, there are four gaps. Firstly, theory is disjointed: VBN-based explanations of moral activation do not incorporate experiential affect (e.g., awe, transcendence, nature connectedness), and it is therefore uncertain how values and emotions together influence behavior post-visit. Secondly, mediating processes are under-defined; Satisfaction and Personal Norms are explained but not typically modeled jointly as parallel pathways from experience to behavior. Third, effects are typically intentions assessed in situ; confirmation of responsible behavior post-visit is still scarce. Fourth, heterogeneity is rarely investigated, restricting conclusions on for whom and under what conditions the effects are strongest. To fill these gaps, this study develops and validates a structural model connecting Environmental Concern (EC), Perceived Trip Quality (PTQ), and Aesthetic/Spiritual Experience (ASE) to Responsible Post-Visit Behavior (RPB) through Satisfaction (SAT) and Personal Norms (PN) as double mediators and investigates subgroup differences through multi-group analysis. The model thereby connects value-based (VBN) routes with affective–experiential processes, considers behaviorally targeted post-visit action, and offers evidence on moderated mechanisms for program design.

Amid ongoing intention–behavior gaps in ecotourism, we suggest that post-visit environmental behavior is optimally predicted by the convergence of cognitive (environmental concern, EC), experiential (perceived Trip Quality, PTQ), and affective–transcendent (Aesthetic/Spiritual Experience, ASE) inputs with two proximal processes—Satisfaction (SAT) and Personal Norms (PN). To this end, we formulated and validated a structural equation model (SEM) connecting EC, PTQ, and ASE to Responsible Post-Visit Behavior (RPB) via SAT and PN. To test this model empirically, we conducted a cross-sectional online survey of adults who had undertaken an ecotourism experience in the last six months, recruited purposively through ecotourism operators, sustainability networks, and university eco-clubs. Validated psychometric scales (e.g., NEP/VBN-based measures, satisfaction scales, and a contextualized awe measure for ASE) developed for post-trip reflective context were used, with five-point Likert formats congruent with the source instruments and SEM conventions. The survey was open for three months (January–March 2025), with two reminder waves ~3–4 weeks apart. Sample size and item design are consistent with contemporary SEM guidelines for model fit and subgroup analyses, which permit estimation of direct and mediated paths and testing of heterogeneity through multi-group analysis.

Though previous research has investigated the short-term effect of ecotourism on learning acquisition or in-trip satisfaction (

Pham & Khanh, 2021;

Romero-Brito et al., 2016;

Sahahiri et al., 2023), few studies have followed up to see how these experiences then transfer to behavior outside the tourism setting. Even fewer have mapped mediating processes, especially affectively charged experience and internalized normative views, in explaining how and why sustainable behavior is or is not taken up following the trip. Limited work also combines both prior values (e.g., concern) and in situ factors (e.g., trip quality, awe) in the same analytical model, especially with strict structural modeling methods. These limitations constrain theory building and applied design (

Sana et al., 2023;

Sitompul, 2024). Although our concern is with proximal, behaviorally specific post-visit change, we recognize that gains of this type can be on a more general transformational trajectory so that awe-suffused experiences and meaning-making are followed by more profound values and identity change. We therefore situate RPB as a proximal post-visit measure that is theoretically consistent with, but analytically separate from, transformation tourism (

X. Chen & Cheung, 2025).

This study has significant theoretical, empirical, methodological, and practical implications. Theoretically, it combines cognitive (EC, PTQ), affective (ASE, SAT), and normative (PN) mechanisms in a single structural model that connects VBN to experience-based affective processes. Methodologically, it uses an adequately powered SEM design with psychometrically sound measures to examine mediation and moderation. Empirically, it introduces ASE as a separate precursor of RPB through SAT and PN. In practice, it provides cues to shape ecotourism such that sustainable alternatives become seen as within reach (through PN-congruent cues) and worthy (ASE/SAT). Supported by brief previews of consequences, environmental attitude, Perceived Trip Quality, and Aesthetic–Spiritual Experiences directly and indirectly affect Post-Visit Responsible Behavior through Satisfaction and Personal Norms. Both affective (SAT) and normative (PN) paths are supported in mediation analyses, and multi-group analyses determine systematic age, gender, education, environmental orientation, and ecotourism experience differences.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents a review of ecotourism, environmental concern, and behavior outcome literature, which serves as a theoretical background for the study.

Section 3 presents the conceptual model and hypotheses.

Section 4 presents the methodology in the form of survey design, sampling, and SEM approach.

Section 5 reports direct effects, mediation analysis, and multi-group comparison results.

Section 6 reflects on real-world applications to tourism stakeholders. Finally,

Section 7 ends with the study limitations and future research recommendations.

4. Data Analysis and Results

The present model analysis was done based on the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) strategy employed in SmartPLS 4 (Version 4.1.1.4). Following

Nitzl et al. (

2016), SEM—specifically its variance-based variant—is widely considered a legitimate research approach for the social science and management disciplines. Partial least squares SEM (PLS-SEM) was applied since it is able to estimate cause-effect relationships and maximize variance explained in endogenous latent variables (

Hair et al., 2006,

2011). Multi-group analysis (MGA) was used to examine subgroup-specific effects, providing contextual differences that may be masked under typical regression approaches (

Cheah et al., 2023). The estimation process followed the guidelines suggested by

Wong (

2013), to properly calculate path coefficients, standard errors, and reliability measures. According to the standards laid down for reflective measurement models, indicator reliability was assessed using outer loadings of more than 0.70 as good enough.

4.1. Common Method Bias (CMB) and Collinearity Diagnostics

In order to check the validity and reliability of the results, systematic measurement for common method bias (CMB) was conducted as per procedural guidance laid out by

Podsakoff et al. (

2003). Harman’s single-factor test was conducted to check if one latent factor explained most of the variance structure. The unrotated principal component analysis revealed that the most dominant factor explained 32.544% of the variance, far from the recommended cut-off of 50%. Although CMB was not critical in the current study, its control increases validity for associations among variables and stability of results by reducing potential measurement biases (

Podsakoff et al., 2003,

2012). Furthermore, we examined collinearity diagnostics. While our indicators are reflective, we report outer VIFs as a redundancy check; all were <3.10 (

Table 2). More critically, inner (structural) VIFs for all sets of predictors ranged from 1.007 to 2.186, well within traditional cut-offs (preferred <3.3; acceptable <5), suggesting that multicollinearity will not spuriously inflate structural paths. Collectively, these statistical and procedural controls ensure that collinearity and CMB will not distort the reported relationships.

4.2. Measurement Model

The first step of the PLS-SEM process is the rigorous test of the measurement model, whereby all the constructs are gauged through reflective indicators.

Hair et al. (

2006) state that this testing encompasses some of the most important metrics such as composite reliability, indicator reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. As observed by

Vinzi et al. (

2010), indicator reliability is an approximation of the ratio of variance of a measured variable accounted for by its underlying construct and is evaluated in terms of magnitudes of outer loadings. As per the guidelines of

Wong (

2013) as well as

Chin (

2009), loadings greater than 0.70 are viewed to be satisfactory. Nevertheless, within social science research,

Vinzi et al. (

2010) observe that there may be cases where indicators fall below this. This removal would be guided by an assessment of their effect on composite reliability and convergent validity to avoid premature deletion.

Hair et al. (

2011) recommend that indicators with 0.40 to 0.70 loading should only be deleted if it significantly improves composite reliability or AVE. According to

Gefen et al. (

2003) guidelines, PTQ5 and ASE5 were eliminated from the analysis since they recorded less than 0.50 factor loadings, as shown in

Table 3. The two of them—PTQ5 and ASE5—consistently produced low outer loadings (<0.50) and poor item–construct relations across iterations and were thus eliminated. Removing them strengthened the AVE and composite reliability for PTQ and ASE without harming discriminant validity (HTMT < 0.85; Fornell–Larcker continued to be met). We re-estimated the model on validity checks with both items; there was no change in the significant pattern of paths or in all hypothesis decisions. For transparency, see the entire cross-loading matrix in

Appendix A,

Table A2.

The reliability assessment in this study used Cronbach’s alpha, rho_A, and composite reliability as the major measures. In accordance with the cut-off point by

Wasko and Faraj (

2005), values above 0.700 were noted for items like Environmental Concern (EC), Perceived Trip Quality (PTQ), Aesthetic/Spiritual Experience (ASE), Tourist Satisfaction (SAT), Personal Norms (PN), and Responsible Post-Visit Behavior (RPB). For the remaining scales, reliability varied between moderate and high, similar to prior empirical results. The rho_A coefficient, theoretically intermediate between Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability, also exceeded 0.70 in all but two instances, consistent with

Sarstedt et al. (

2021) reliability results and

Henseler et al. (

2015).

Convergent validity was attained since the average variance extracted (AVE) values for the majority of the constructs exceeded the 0.50 mark advocated by

Fornell and Larcker (

1981). Where the AVE was marginally less than this, the composite reliability was still in excess of 0.60, which was the acceptable limit for convergent validity according to the same authors. Discriminant validity was examined via inter-construct correlation analysis, where the square root of the AVE of every construct was greater than its correlations with the other constructs—a method based on the

Fornell and Larcker (

1981). These findings were also validated using the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations, as suggested by

Henseler et al. (

2015), where all HTMT values were below the conservative threshold of 0.85, as presented in

Table 4 and

Table 5.

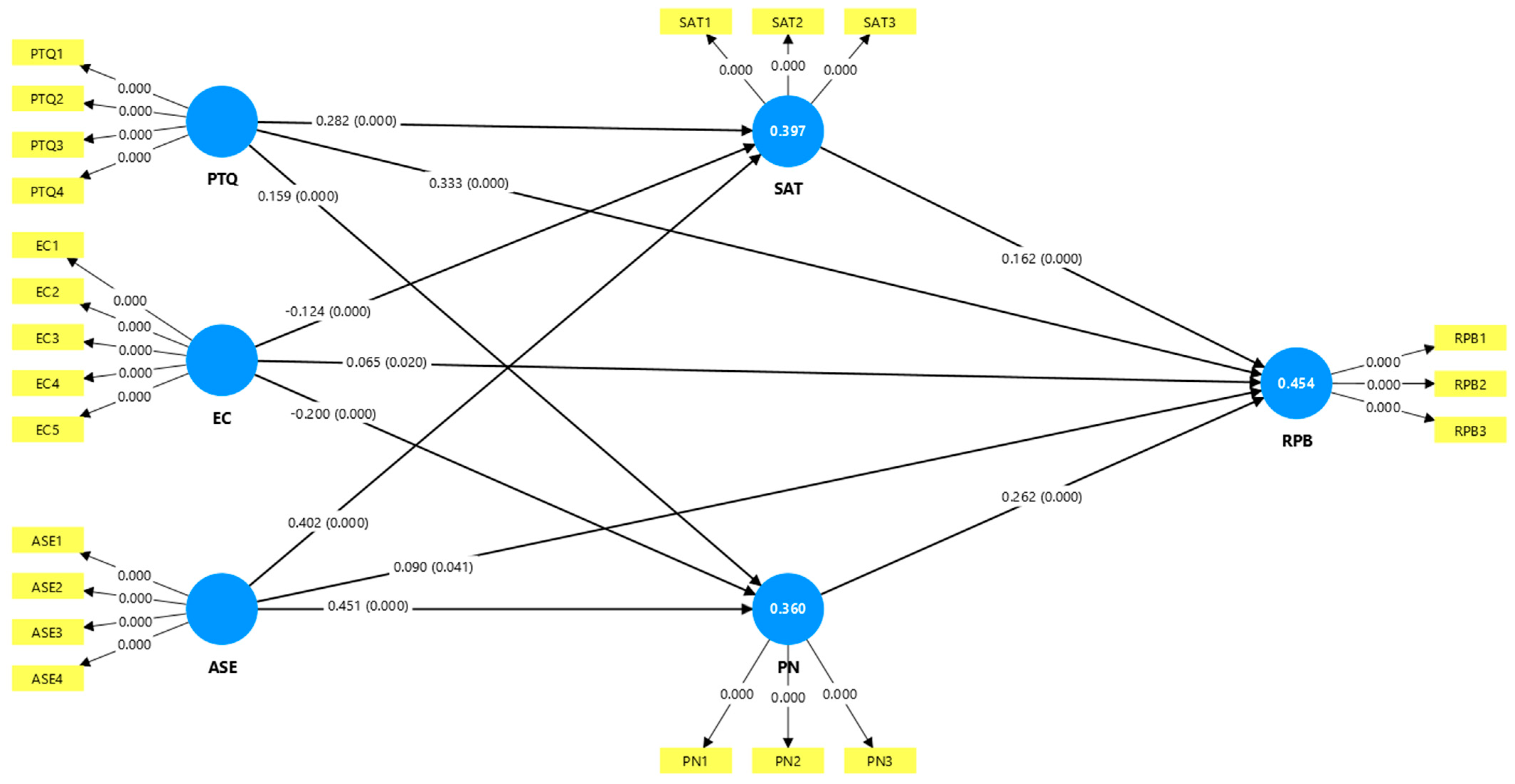

4.3. Structural Model

The structural model was assessed based on the coefficient of determination (R

2), predictive relevance (Q

2), and statistical significance of the path coefficients, according to

Hair et al.’s (

2011) criteria. In the current study, the R

2 values were 0.454 for Responsible Post-Visit Behavior (RPB), 0.360 for Personal Norms (PN), and 0.397 for Tourist Satisfaction (SAT), indicating moderate explanatory power within the desirable range of 0 to 1. The Q

2 values that measure the predictability of the model by the blindfolding procedure also indicated good results: 0.385 for RPB, 0.352 for PN, and 0.388 for SAT, indicating moderate to high predictive power.

To verify the model to an even greater extent, hypothesis testing was employed for estimating structural relations among the latent variables and for testing their significance. Path coefficients were estimated with the nonparametric bootstrapping procedure, according to

Sarstedt et al.’s (

2021) recommendation. Mediation effects were tested based on a one-tailed, bias-corrected bootstrapping procedure for 10,000 resamples, following

Preacher and Hayes’ (

2008) and

Streukens and Leroi-Werelds’ (

2016) recommendation. To determine the direct associations among the predictor and outcome variables in the hypothesized model, partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) path analysis was performed. Standardized path coefficients (β), standard errors, t-values, and significance levels (

p-values) were estimated by 10,000-sample bias-corrected bootstrapping (

Table 6).

As

Table 6 shows, all the hypothesized direct effects were statistically significant and supported. Environmental Concern (EC) had a weak but positive impact on RPB (β = 0.065, t = 2.056,

p = 0.020), and this provided evidence for H1. Perceived Trip Quality (PTQ) was the most significant predictor of the exogenous variables, and it had a significant and strong impact on RPB positively (β = 0.333, t = 8.618,

p < 0.001), lending support to H2. Aesthetic/Spiritual Experience (ASE) also had a direct significant impact on RPB (β = 0.090, t = 1.739,

p = 0.041), lending support to H3. With regard to the mediating constructs, SAT was highly correlated and significantly related to RPB (β = 0.162, t = 4.190,

p < 0.001), confirming H4a. Likewise, PN was highly and significantly related to RPB (β = 0.262, t = 6.267,

p < 0.001), confirming H4b.

These findings underscore the multi-determined and multifaceted character of responsible behavior formation in response to ecotourism participation, showing how such behavior is not merely shaped by the content or excellence of the experience itself, but through an interactive process involving reflective judgment, affective response, and strongly internalized moral duty. Specifically, cognitive-emotional assessments—i.e., tourists’ aesthetic engagement and satisfaction—and normative beliefs—assessed through personal moral norms activation—are equally responsible for post-trip intentions to behave in an eco-friendly way. In other words, meaningful, reflective, and emotionally evocative ecotourism experiences are capable of activating inner value systems and promoting a stronger commitment to environmentally sound actions during the after-trip phase. A visual illustration of the results is depicted in

Figure 2.

4.4. Mediation Analysis

To measure the mediating roles of Tourist Satisfaction (SAT) and Personal Norms (PN) between exogenous variables and Responsible Post-Visit Behavior (RPB), a bootstrapping test with resamples of 10,000 was utilized.

Table 7 displays the direct effects as well as the total effects.

There were also significant mediation effects for each of the hypothesized pathways. That is, Environmental Concern (EC) significantly indirectly affected RPB through both SAT (β = 0.020, t = 3.129, p = 0.001) and PN (β = 0.052, t = 3.841, p < 0.001), thus supporting Hypotheses H5a and H5b. Interestingly, however, the direct impact from EC to RPB was still statistically significant (β = 0.065, t = 2.056, p = 0.020), which means that there was partial mediation. This indicates that EC affects RPB directly as well as indirectly through the mediating mechanisms of satisfaction and internalized norms. In the same vein, Perceived Trip Quality (PTQ) had its influences through SAT (β = 0.046, t = 3.268, p = 0.001) and PN (β = 0.042, t = 3.358, p < 0.001), and a significant and strong direct influence was also found (β = 0.333, t = 8.618, p < 0.001), pointing towards partial mediation. Hypotheses H6a and H6b were confirmed. Aesthetic/Spiritual Experience (ASE) also had an indirect influence on RPB via SAT (β = 0.065, t = 3.792, p < 0.001) and PN (β = 0.118, t = 5.075, p < 0.001), confirming Hypotheses H7a and H7b. The direct impact from ASE to RPB was still significant (β = 0.090, t = 1.739, p = 0.041), ascertaining partial mediation in this instance as well.

Together, these findings establish that both mediators, Tourist Satisfaction and Personal Norms, are significant to account for the way antecedent factors affect responsible behavioral intentions following ecotourism experiences. Yet, the residual effect of the direct paths indicates that these effects are not solely mediated, but rather partially directed through cognitive-affective and normative ones.

4.5. Multi-Group (MGA) Analysis

Group differences in path coefficients were also tested with SmartPLS based on the bootstrap MGA procedure, 10,000 subsamples, BCa bootstrap confidence intervals, fixed seed, and parallel processing. In line with

Hair et al. (

2011), we report Δβ = β_GroupA − β_GroupB and the SmartPLS one-tailed BCa

p-value, testing whether the estimated direction of Δβ is not equal to zero. The sign of Δβ indicates the stronger group for the corresponding path. Measurement invariance was established prior to MGA, and only theoretically supported paths were compared. In order to determine if the structural relationships differed between demographic and experiential subgroups, a set of multi-group analyses (MGA) was performed using the PLS-MGA method with a significance criterion of

p < 0.05 (

Table 8).

There were significant differences between the four age cohorts (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54). The effect of Aesthetic/Spiritual Experience (ASE) on Tourist Satisfaction (SAT) was more pronounced for younger tourists, and specifically for the 18–24 cohort than for 25–34 (Δβ = 0.421, p = 0.003) and 35–44 (Δβ = 0.332, p = 0.002). Likewise, the SAT → RPB path was stronger for younger age groups (e.g., 18–24 vs. 25–34: Δβ = 0.333, p = 0.003). The PTQ → SAT connection was stronger for the 25–34 age group compared to 18–24 (Δβ = −0.403, p = 0.003) and 35–44 (Δβ = 0.415, p < 0.001), indicating developmentally different satisfaction processes. The ASE → RPB trajectory also differed considerably, with 25–34 having a stronger influence than both the 18–24 (Δβ = −0.331, p = 0.011) and older cohorts. PTQ and EC also had stronger influences on PN for younger cohorts, with EC → PN being stronger in 18–24 than 35–44 (Δβ = 0.243, p = 0.024) and 45–54 (Δβ = 0.477, p = 0.002).

MGA showed gender moderation for several relationships. ASE influenced RPB more strongly in males (Δβ = 0.364, p < 0.001), while SAT influenced RPB more strongly in females (Δβ = −0.342, p < 0.001). In the same vein, PTQ influenced RPB (Δβ = 0.231, p = 0.002) and PN (Δβ = 0.213, p = 0.006) more strongly in males. In contrast, women showed more robust links from EC to both SAT (Δβ = −0.168, p = 0.012) and RPB (Δβ = −0.159, p = 0.013), implicating gendered pathways in affective and normative processing.

Aggregate to low, moderate, and high environmental orientation, the model showed several moderation effects where PTQ → PN was higher for Low vs. High (Δβ = −0.295, p = 0.006) and Low vs. Moderate (Δβ = 0.217, p = 0.013) and EC → PN was highest for High vs. Low (Δβ = 0.395, p = 0.012) and High vs. Moderate (Δβ = 0.359, p = 0.024). ASE had larger effects on SAT for the Low than High (Δβ = −0.331, p = 0.032) and Moderate (Δβ = −0.232, p = 0.014) groups. ASE → PN was stronger for Low than High (Δβ = 0.203, p = 0.042) and Moderate (Δβ = 0.194, p = 0.046). Other moderated effects were PTQ → RPB (Low vs. High: Δβ = −0.252, p = 0.046), SAT → RPB (Low vs. Moderate: Δβ = 0.258, p = 0.001), and EC → RPB (Low vs. Moderate: Δβ = −0.131, p = 0.044). PN → RPB (Δβ = 0.151, p = 0.035) and ASE → RPB (Δβ = −0.288, p = 0.004) also differed significantly between groups.

Newly experienced ecotourists showed more significant effects of ASE → SAT (Δβ = −0.183, p = 0.026), while repeat ecotourists showed a relatively stronger PTQ → SAT relationship (Δβ = 0.132, p = 0.051). In another comparison by history of past ecotourism visits (<3 vs. >3), EC → SAT was slightly more powerful for first-time tourists (Δβ = 0.107, p = 0.052), and so was PN → RPB (Δβ = 0.128, p = 0.055), and the implication is that first-time ecotourists are more affective and morally sensitive to environmental appeals.

The level of education strongly moderated some pathways. EC → SAT was greater for the bachelor’s level than for doctorate (Δβ = 0.419, p = 0.010), master’s (Δβ = 0.228, p = 0.012), and high school (Δβ = 0.258, p = 0.009). PN → RPB was higher in bachelor’s graduates compared with doctoral (Δβ = 0.213, p = 0.044), high school (Δβ = 0.203, p = 0.031), and PhD candidates (Δβ = 0.541, p = 0.023). EC → PN path was higher for bachelor’s compared with high school (Δβ = 0.314, p = 0.004) and doctoral-level participants (Δβ = 0.271, p = 0.073). In addition, ASE → PN (Δβ = 0.283, p = 0.005), ASE → RPB (Δβ = −0.475, p = 0.050), and PTQ → RPB (e.g., PhD versus high school: Δβ = 0.526, p = 0.014) were significantly moderated by level of education. Lastly, PTQ → PN was significantly greater in PhD applicants than in bachelor’s (Δβ = 0.651, p = 0.028) and doctorate degree holders (Δβ = 0.664, p = 0.029).

Collectively, these findings suggest that demographic and experience factors—i.e., age, gender, environmental orientation, education, and previous exposure—impact the psychological mechanisms that link ecotourism experiences to sustainable behavioral intentions.

5. Discussion

The structural model results also yield strong empirical evidence for hypothesized direct effects between cognitive, affective, and normative predictors and Responsible Post-Visit Behavior (RPB). The five direct paths—Environmental Concern (EC), Perceived Trip Quality (PTQ), Aesthetic/Spiritual Experience (ASE), Satisfaction (SAT), and Personal Norms (PN)—were all significant predictors of RPB, consistent with the theoretical expectation that pre-trip disposition and in situ experience contribute to the formation of sustainable behavior outside of the ecotourism context.

5.1. Environmental Concern, Perceived Trip Quality, and Aesthetic and Spiritual Experience as Robust Predictors of Post-Visit Behavior

Ecological concern showed a statistically significant but weak direct relationship with RPB, as VBN theory suggests that concern is a general motivational context for pro-environmental behavior in favor of H1. We identify EC as a secondary rather than a primary space action motivator by the low coefficient. This is consistent with evidence for the intention–behavior gap, in which concern and intention have to be enabled conditions to be translated into action. Consistent with this, EC’s most reasonable role is indirect—augmenting the impact of responsibility, awareness, and experience quality when available options and efficacy cues are present—than as a strong independent predictor. This more conservative understanding avoids overemphasizing the relationship and better accommodates theories that highlight perceived control and situational enablement in tourist contexts (

Landon et al., 2018;

Oviedo-García et al., 2017;

Ribeiro et al., 2025;

Stern et al., 1999). Yet, the low proportionate path coefficient indicates that worry, standing on its own and lacking context, perhaps may not always be enough to stimulate behavior change—a pattern replicated in the literature across the intention–behavior gap (

Assaker, 2025;

Memon et al., 2020). The result places the spotlight on the need to locate concern within contexts of transformation that mobilize moral engagement and emotional salience.

Perceived Trip Quality was the most significant direct predictor of RPB, supporting H2 and aligning with past research establishing the relationship between positive ecotourism activity evaluations and behavioral intention and loyalty (

Ballantyne & Packer, 2005;

Kim & Thapa, 2018). This outcome points out that tourists who value their ecotourism experience as efficiently run, emotionally meaningful, and educationally stimulating are more likely to translate these experiences into sustainable post-visit behavior. This is also consistent with the belief that high-quality experience constitutes a cognitive anchor—whereby tourists can integrate learning, assign meaning, and re-emphasize ecological values through reflection. Practically, this highlights the importance of experience design in the creation of behavioral outcomes and sets the core importance of interpretive messaging, service quality, and meaning-making direction within ecotourism programming (

Oviedo-García et al., 2017;

Sarangi & Ghosh, 2025).

Aesthetic/Spiritual Experience also directly influenced RPB significantly, supporting H3. Its use, despite the smaller effect size compared to PTQ or PN, indicates the heretofore untested unique contribution of awe, nature connectedness, and spiritual engagement in promoting environmental stewardship (

Coghlan et al., 2012;

Yaden et al., 2019). These emotional encounters seem to be drivers of self-transcendence, re-directing tourists’ horizons away from short-term hedonism and toward long-term ecological stewardship. This resonates with proposals for the integration of emotional and symbolic aspects into ecotourism frameworks (

C.-F. Chen & Tsai, 2007;

Mohammad Nasir et al., 2024), and is consistent with the Experience Economy framework, wherein authentic, emotionally resonant experiences have lasting effects on behavior (

Sarangi & Ghosh, 2025). Aesthetic–Spiritual Experience offers an affective path. Awe and feeling of oneness appear to shift attention away from hedonics in the short term toward stewardship, augmenting cognitive judgments of quality. Combined, the findings point to a hybrid mechanism: cognitive appraisals (PTQ) determine meaning; affective–transcendent states (ASE) prime for moral engagement; concern provides a motivational context.

5.2. Tourist Satisfaction and Behavioral Outcomes

As H4a anticipated, Tourist Satisfaction shows a clear positive association with RPB, thus a proximal cognitive–affective mediator of experience and behavior. The result is consistent with more recent research (

Nguyen et al., 2025;

Sarangi & Ghosh, 2025), which has established that satisfaction, if based on emotional meaning and perceived value, results in greater behavioral commitment. But satisfaction in itself will not necessarily lead to pro-environmental behavior unless there is the reinforcement of moral duty or values convergence, according to

Hansen et al. (

2024). Thus, though this positive assessment of experience is significant, it is best when it is matched with other normative and affective modifications.

Personal Norms directly affected RPB to a very high level, thus supporting H4b and illustrating their pivotal status in VBN and VIP theories (

Mandić & McCool, 2023;

Yin, 2024). Such tourists who felt a sense of moral duty to behave in accordance with their environmental values were much more likely to exhibit sustainable behavior post-trip. This result indicates a shift away from out-driven motivations (e.g., social norms) to internalized moral requirements, and is consistent with

Javed et al.’s (

2025) and

T. T. T. Thuy et al.’s (

2025) findings, assuming Personal Norms are particularly powerful in effort-, consistency-, or sacrifice-based high-cost behaviors. It is striking to note how PN’s high predictive value is evidence that ecotourism interventions that engage with personal responsibility—either through reflection, messaging, or involvement—can be more effective at bringing about long-lasting behavior change.

Together, these direct effects supply empirical support for a hybrid behavior model by combining cognitive (EC, PTQ), affective (ASE, SAT), and normative (PN) measures. The findings enhance extended VBN models with aesthetic/spiritual measures and verify the multi-dimensionality of sustainable action. Theoretically, the findings cross experience-based and value-based paradigms by providing a more integrated view of the mechanisms underlying pro-environmental action in ecotourism settings.

In practice, the results have several actionable implications: (1) improving the quality and effectiveness of ecotourism experiences can cause behavior change; (2) adding emotionally authentic and spiritually meaningful aspects can strengthen tourists’ sustainability pledge; and (3) through individuals’ own moral norms through education materials, reflective practices, or participatory conservation can be the most powerful conduit to the intention–behavior gap, which will be discussed in further detail in the next section.

5.3. Mediation Analysis Results

Mediation analysis provides strong evidence that Tourist Satisfaction (SAT) and Personal Norms (PN) are strong psychological mediators through which Environmental Concern (EC), Perceived Trip Quality (PTQ), and Aesthetic/Spiritual Experience (ASE) influence Responsible Post-Visit Behavior (RPB). All the hypothesized indirect effects were statistically significant, and in every instance, mediation was partial—i.e., the mediators conveyed a significant share of the effect, with direct influences remaining significant at the same time.

For Environmental Concern, PN and SAT were equally robust mediators of its effect on RPB. The EC → PN → RPB chain was more robust than the EC → SAT → RPB chain, indicating internalized moral responsibility, has a more central function to serve as an intervening force in bridging concern and action than emotional satisfaction. These results are consistent with the value–belief–norm (VBN) theory, which suggests that norms are a proximal motivator of environmentally important action, particularly in those with already existing ecological values (

Landon et al., 2018;

Ribeiro et al., 2025;

Stern et al., 1999). The dominant EC on SAT on the RPB pathway also demonstrates the experiential reinforcement hypothesis (

Ballantyne & Packer, 2005), where experiential meaningful travel is able to make the affective significance of past concern larger.

Perceived Trip Quality indirectly affected RPB through SAT and PN, confirming H6a and H6b. It appears that positive ecotourism experiences not only enhance emotional satisfaction but also internalization of value as a double stimulus for behavioral commitment. Consistent with cognitive-affective attitude formation theories (

Kim & Thapa, 2018;

Mandić & McCool, 2023;

Wut et al., 2023), trip quality seems to provide a tangible evaluation system by which the tourist exists and attributes meaning to his/her experiences, arriving at affective opinions and normative change. Notably, the stability of the direct effect suggests that there are aspects of trip quality, perhaps logistical convenience, comfort, or perceived value, that may affect behavior independent of more profound psychological change, something that future research would have to distinguish out more specifically.

Aesthetic/Spiritual Experience provided the largest overall mediation effect, with the ASE → PN → RPB path larger than all other indirect paths. This is in line with recent awe, nature connectedness, and self-transcendence for tourism studies (

Coghlan et al., 2012;

Yaden et al., 2019) and fits with the idea that emotionally resonant and spiritually profound experiences are best for evoking moral norms. The SAT → ASE → RPB process was also significant, again showing the twofold affective-normative process by which such experiences impact outcomes. These findings add to the growing demands that transformative emotional design be included in ecotourism experiences to enable post-visit behavioral commitments (

Coghlan et al., 2012;

Lu et al., 2017;

Yaden et al., 2019). These results make a series of theoretical contributions. They first set out the mediating role of both affective satisfaction and moral personal norms in the use of mainstream VBN models to apply to experience-based and richly emotional antecedents. They second point out the fact that mechanisms of experience do count—not so much in the transmission of information but in invoking internalized change conducive to longer-term behavior change.

5.4. Multi-Group Analysis (MGA) Results

The multi-group analysis revealed that various psychological mechanisms between the ecotourism experience and Responsible Post-Visit Behavior (RPB) were significantly moderated by demographic and experiential factors. These results capture the heterogeneity of tourist cognitive processing of environmental experience and formation of behavioral intentions and have significant implications for segmentation strategy and person-fit intervention design. There were also steady differences between age groups in terms of ASE and PTQ effects on SAT and RPB. 18- to 24-year-olds had more intense emotional reactions to ASE (Δβ = 0.421 compared with 25–34), and 25- to 34-year-olds had greater ASE → RPB effects than both the younger and the older groups. These results are consistent with lifespan developmental theories of peak emotional identification and identity exploration during early adulthood, thus making such a group highly susceptible to nature-based experiences (

Sitompul, 2024;

Wut et al., 2023). EC and PTQ effects on PN were also more significant for younger age groups, indicating that internalized environmental norms develop earlier in life and are more open to change at the outset of identity formation.

The gendered MGA manifested differential motivational processes. Men exhibited greater ASE → RPB association, while women exhibited greater SAT → RPB linkage. This can be understood as gendered emotional processing styles wherein women are more attuned to affective satisfaction and men are more propelled by experiential aesthetics (

Brochado, 2019;

Coudounaris & Sthapit, 2017). Furthermore, EC elicited more powerful effects on SAT and RPB among women and implies that ecological worry provokes affective and behavioral responses more strongly in women, as seen in earlier work on gendered sensitivity to the environment.

Environmental orientation emerged as a potent moderator, particularly for affective and normative channels. Low ecological orientation visitors had weaker EC → PN and PTQ → PN associations but stronger ASE → SAT effects, suggesting more dependence on emotional as opposed to value-based processes. These trends affirm dual-process theories, in which low-preparedness individuals are more susceptible to experiential stimuli and high-preparedness individuals more on beliefs and values (

Folmer et al., 2013;

Jorgenson et al., 2019). This increased susceptibility of low-orientation visitors to affective cues also has strategic implications: immersive, awe-inspiring experiences can serve as effective gateway portals to environmental learning.

Less experienced and novice ecotourists indicated higher emotional and normative sensitivity, as evidenced by stronger ASE → SAT and EC → SAT relationships. This supports the argument that early experiences shape early norms and attitudes and helps arguments direct towards novice ecotourists transformational propositions (

Ballantyne & Packer, 2005). The decline effects noticed among repeat visitors also confirm the habituation hypothesis, where familiarity over time may decrease novelty and affective importance.

Educational level moderated a number of principal paths, especially those involving EC, PN, and ASE. Bachelor-degree responders consistently exhibited more intense normative and affective paths compared with the higher and lower education groups. To illustrate, the EC → PN and PN → RPB paths were significantly stronger in bachelor-level responders. To our surprise, the PhD students demonstrated smaller ASE → RPB and PN → RPB effects, perhaps because of cognitive filtering or detachment because of disciplinary skepticism or desensitization to persuasion mechanisms. The findings indicate that education affects not just environmental literacy but also the extent to which individuals internalize and respond to ecotourism experience (

Pham & Khanh, 2021;

Sana et al., 2023;

Wut et al., 2023).

Collectively, the MGA takes a systemic segmentation into account: novice and inexperienced ecotourists are most vulnerable to affective pathways (ASE → SAT) that induce early norm formation, while high environment-focused visitors or well-educated ones process experience through cognitive and normative channels (EC/PTQ → PN → RPB). Men are more immediately affected by experience-driven awe, whereas women embed environmental concern and satisfaction in action more deeply. These patterns suggest a step-stair model of change: start with strong, awe-some cues for new-comers or low-orientation visitors, and supplement with value-congruent quality signals and selective norm activation to build on strong, post-visit action—dosing novelty and stewardship functions for repeat visitors to counteract habituation (

Table 9).

6. Practical Implications

The results of the research provide informative input to the various stakeholders involved in planning, delivering, and regulating ecotourism experiences and sustainability programs. Through the mapping of cognitive, affective, and normative processes that form Responsible Post-Visit Behavior (RPB) and demographic and experiential differences in these routes, the research provides an evidence-based model for more focused interventions. The consequences are grouped into three general categories: policy formulation, managerial ecotourism practices, and environmental education and community outreach.

6.1. Implications for Policymakers

For policy makers wishing to encourage sustainable tourist behavior, the findings of the study suggest the need to influence affective experiences alongside the personal norms of tourists. That Environmental Concern (EC) and Personal Norms (PN) are such significant predictors of responsible behavior suggests that policy needs to extend beyond the provision of information and encourage reflective consideration of environmental values. This can be facilitated by tourism and environment ministries by subsidizing nature-based recreation that incorporates the possibilities of affective engagement and moral reflection—e.g., guided interpretation, cultural narrative, and spiritual immersion. Policies legitimizing and normalizing satisfaction-facilitating practices, particularly for young and novice ecotourists, can foster environmental commitment in the long run (

Sitompul, 2024;

Stronza et al., 2019). Additionally, demographic variations in psychological processing indicate that inclusive tourism policy must consider age, level of education, and environmental orientation in guiding communication campaigns and public awareness programs. Additionally, the fact that some of the main impacts are through personal norms indicates that values-based policy framing (civic duty, stewardship, intergenerational equity, for example) will be a more fruitful approach than utilitarian or information-only campaigns. Policy interventions that engage these moral values through message-or experience-based nudges may achieve more profound behavioral change (

Wondirad, 2019).

6.2. Implications for Business Managers and Ecotourism Providers

For destination managers and ecotourism operators, the findings of the study provide explicit directions on how tour experiences should be designed in order to induce post-trip sustainable behavior. The significant and strong path from Perceived Trip Quality (PTQ) and Aesthetic/Spiritual Experience (ASE) to Satisfaction (SAT) and RPB indicates how central experience design is to sustainability outcomes. Investments in scenery, emotional engagement, and cultural authenticity are not just attractive from a customer satisfaction point of view but also as tools for promoting pro-environmental behavior.

That satisfaction mediates between experiential antecedents and responsible behavior implies that providers must attend not only to logistical quality (i.e., service, comfort), but also to creating emotionally compelling and pedagogical experiences. Programs that connect personal enjoyment with ecological contemplation—e.g., nature journaling, environmental rituals, or post-activity reflection—can heighten satisfaction while reinforcing environmental norms (

Wut et al., 2023;

Zhang & Deng, 2024).

Notably, multi-group differences within the model show that segmentation of customers can enhance the performance of ecotourism experiences. Younger travelers (18–24) were more sensitive to aesthetic and emotional elements, whereas older travelers had greater concern for satisfaction and value consistency. Managers can apply this knowledge to product segments: emotionally arousing, novelty-experience activities for younger segments, and value-confirming, learning-based activities for older or experienced consumers.

Also, the fact that novice ecotourists and those with fewer than three previous trips were more susceptible to both satisfaction and norm formation suggests that initial ecotourism experiences are a formative touch point. Firms should place special emphasis on familiarizing novice ecotourists, and these initial exposures should be carefully designed, emotively engaging, and with clear connections made to sustainability principles.

6.3. Implications for Environmental Educators and Campaign Designers

Personal Norms and Satisfaction’s mediator effects also promise to be useful for environmental educators and NGOs engaged in behavioral change initiatives. What the study indicates is that responsible behavior is not merely a function of early concern with the environment but is conditioned and facilitated through experiential learning and emotional attachment. Environmental education must, therefore, embrace experiential pedagogies such as ecotourism study tours, field-reflection exercises, and local community-based projects to bring about internalized commitment towards environmentally sustainable behavior.

Consistent with the increased emotional and normative sensitivity among women and youth subjects, education campaigns may look toward using emotionally engaging narratives and peer-to-peer learning presentations as forms of outreach, particularly in youth programs (

Wut et al., 2023;

Zhang & Deng, 2024). In addition, the extensive pathways from EC and PTQ to PN indicate that emphasizing the personal importance and richness of ecological experience—over its informational content, per se—can help increase perceived moral commitments to act ecologically.

Educational activities must also be directed towards lower-engagement groups, including those with low environmental orientation or limited prior experience with ecotourism. These groups were found within the study to be more radically affected by aesthetic and emotional concerns than by normative pressures. Thus, initial contact can include recourse to grabbing attention and engaging emotionally through experiential involvement or emotionally resonant storytelling before gradually adding moral and behavioral norms.

Lastly, collaboration between educators and ecotourism operators could further enhance the strengths of the two fields. For example, planning visitor experience in synchronization with curriculum objectives or developing outreach materials that link trip experience to daily environmental habits can build post-visit behavioral spillover.

7. Conclusions

In this study, we investigated the process by which ecotourism experience is converted into Responsible Post-Visit Behavior (RPB) through a double-sidedness mechanism based on affect (Satisfaction, SAT) and morality (Personal Norms, PN). Employing SEM on a large sample of ecotourists, we identified that Environmental Concern (EC), Perceived Trip Quality (PTQ), and Aesthetic/Spiritual Experience (ASE) each have direct effects on RPB and indirect effects through SAT and PN. Among the mediators, PN always showed a stronger path, and internalized obligation was stressed as playing a significant role in continuing behavior post-trip. Multi-group analyses reported consistent variation by age, gender, education, experience, and environmental orientation, suggesting that affective and normative paths are not similarly activated for varying visitor segments. In theory, the model combines experience-based (NAM) and value-based (VBN) approaches; in practice, it guides policymakers and operators towards good-quality experiences with norm-activating sparks making sustainable options simple, transparent, and compelling.

Limitations and Future Directions

While this study takes important steps towards an understanding of how ecotourism experiences affect responsible post-visit action, several areas remain open to future research that can consolidate and expand upon the current findings. Although this investigation contributes to the literature on how ecotourism experiences relate to Responsible Post-Visit Behavior (RPB), a number of design features temper generalizability and causal inference, and, in doing so, intimate directions for future research. First, the cross-sectional survey design cannot determine temporal precedence, especially for mediation pathways through Satisfaction (SAT) and Personal Norms (PN). As such, the indirect effects presented herein are to be interpreted as statistical (not temporal) mediation. Future studies are advised to use time-separated or longitudinal designs (i.e., pre-trip on in-situ and eventually on post-trip waves), cross-lagged panel models, or latent-growth methods in order to examine directionality, stability, and the difference between short-term priming vs. enduring change (

Wut et al., 2023;

Zhang & Deng, 2024). Second, all the constructs were obtained from a single source at a single point in time. While we pre-tested for common-method bias, post hoc tests such as Harman’s one-factor are restrictive. To minimize social-desirability, recall, and consistency motives, future studies need to (i) incorporate marker variables and procedural remedies (temporal and psychological distance between the surveys), (ii) incorporate a social-desirability scale as a method of modeling bias in an explicit manner, and (iii) triangulate using objective or trace data (e.g., conservation partner donations, carbon-offset purchases, public-transit fares, citizen-science participation, or smart-card/booking records). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) and short in-app cues during/after task will also prevent recall error (

Sahahiri et al., 2023;

Stronza et al., 2019). Third, the single-country setting and purposive/snowball sampling design restrict representativeness and enable self-selection (ecologically oriented tourists potentially over-sampled). Future studies ought to use probability or quota sampling at multiple sites across different destinations and management regimes, include a priori power reporting of comparisons of sub-groups, and perform cross-cultural replications in order to enable policy and cultural contingencies to be examined. Fifth, the model specification did not include potentially important antecedents and constraints (e.g., subjective norms, habit strength, perceived costs/affordances). Including such variables, investigating endogeneity (e.g., Gaussian-copula or instrumental–variable corrections) and assessing unobserved heterogeneity (e.g., FIMIX-PLS or latent-class SEM) would improve inference. In multi-group research, future analyses would also be improved by including effect sizes with confidence intervals and family-wise error control (e.g., Holm–Bonferroni) for multiple tests (

Sana et al., 2023;

Wut et al., 2023). Lastly, to close the gap between association and effect, managers and scientists ought to try out field interventions such as framing eliciting awe and linking it with personal norms, promise of commitment, norm-prompts at touchpoints, and “easy-first” friction-reducing alternatives, and test them with A/B tests or cluster-randomized trials with behavioral outcomes. All these will elucidate mechanisms, increase generalizability, and guide the design of scalable, evidence-based interventions to translate ecotourism experiences into long-lasting pro-environmental behavior (

Rhama, 2020;

Sitompul, 2024). Subsequent research needs to include explicit transformational processes (e.g., identity work, critical reflection) and employ time-discrete or longitudinal mixed methods to determine durability and spillovers “beyond the vacation,” thus making our ASE on the PN pathway directly transferrable to longer-term transformation. The development of new digital and hybrid ecotourism models—like virtual visitation, immersive applications, and gamified sustainability interactions—poses new research questions. Experiments on whether these digital experiences can also provide the same amounts of satisfaction and norm activation as traditional in vivo ecotourism may offer insights into how technology can spread environmental messaging to a wider audience that cannot otherwise travel. Also, research in the future can look at spillover from attitudes formed due to ecotourism. For example, how do people who become environmentally aware during a vacation take it beyond the vacation (e.g., at the supermarket, political activism, or household energy consumption). Looking at the diffusion of that behavior could inform larger-scale sustainability education initiatives (

Liu & Chamaratana, 2024;

Pham & Khanh, 2021).

This research demonstrates that a well-designed ecotourist experience, when combined with personal norm activation, leads to increased levels of responsible post-visit behavior. Trip quality and aesthetic–spiritual experience work through satisfaction and even more through personal norms. In practice, operators and policymakers must integrate high-quality service and interpretation with pro-environmental low-friction options and salient norm prompts, segmented by visitor type. Lastly, our research provides a step-by-step guide to converting encounter into commitment: When meaning, quality, and moral purpose converge, care continues on beyond the trip. The path of inquiry does not stop here. In the future, research—through time and place, emotion and structure—can shed light on the way wonder sparks values and the way action radiates outward from one step in the forest. Rather than a projection of what is, let evidence lead us to a more accountable relationship between people and the places they travel to.