Abstract

This study aims to investigate how tourists articulate their ecotourism experiences through online reviews of coastal Karnataka. As one of India’s most favored domestic destinations since the 1960s, coastal Karnataka is renowned for its scenic shoreline, unique biodiversity, and diverse ecotourism experiences along a 320 km stretch of the Arabian-Sea rim spanning across the Uttara Kannada, Udupi, and Dakshina Kannada districts. Despite the growing popularity of ecotourism and sustainable travel, limited research has examined how tourists share ecotourism concepts via online reviews. Employing content analysis through the Leximancer tool, this study examines 1843 online reviews from 80 eco-resorts and homestays listed on TripAdvisor® to identify emerging themes from interconnected concepts and assess the extent to which ecotourism values are reflected. The findings highlight several themes out of which “place”, “food”, “resort”, and “rooms” were the dominant ones. Notably, this study also revealed minimal references to coastal conservation or sustainability. The analysis offers several theoretical contributions to the ecotourism literature by demonstrating the implication of construal level theory (CLT) and the use of Leximancer in analyzing large-scale travel data. This study also provides meaningful insights for the tourism service providers to use online review data to enrich tourist experiences and outlines actionable strategies for strengthening the visibility of coastal conservation efforts and promote ecotourism advocacy.

1. Introduction

The tourism industry has been expanding globally and is deemed to be one of the fastest growing sectors by contributing substantially to GDP and employment generation. The UN Tourism (2025) board states that in 2024, there were more than 1.4 billion international tourist visits across nations, indicating a strong resurgence of travel culture post the pandemic. Over the last few years, especially after the pandemic, ecotourism has gained significant popularity among tourists (Dinç et al., 2023; Yaziz et al., 2025). In 2023, the global ecotourism market size was valued at USD 216.49 billion and it is projected to grow up to USD 759.93 billion by 2032 (Fortune Business Insights, 2025). Ecotourism is defined as “responsible travel to natural areas that conserves the environment and improves the welfare of the local people” (The International Ecotourism Society, 2015). It focuses on developing an environmentally and economically sustainable sector which emphasizes ‘education and interpretation’ of the natural ecosystem (Salman et al., 2024). It promotes the sustainable conservation of biodiversity by encouraging tourists and locals to safeguard the natural and cultural heritage (M. Das & Chatterjee, 2015). Furthermore, ecotourism helps in the creation of diverse employment opportunities for the local residents of a tourist destination by promoting education and poverty alleviation (Surendran & Sekar, 2011).

In Asian countries, ecotourism has become one of the fastest growing subsectors in the tourism industry over the last decade, as it has helped in fostering employment and has contributed to the financial well-being of the host communities (Salman et al., 2020). The Asia Pacific ecotourism market is projected to grow at a CAGR of 16.8% from 2024 to 2030, with China expected to lead in terms of revenue by 2030 (Grand View Research, 2025). However, owing to its cultural and traditional diversity along with varied physiography, India is also now one of the frontrunners in the ecotourism sector (D. Das & Hussain, 2016) with an emerging regional ecotourism market (Grand View Research, 2025). With the intensifying global climate crisis, India is proactively tackling the challenge by embracing sustainable practices across industries, particularly in the hospitality and tourism sectors (ETTravelWorld, 2024). As a result, the Indian ecotourism market is expected to grow exponentially and reach USD 4.55 Billion by 2027 (ETTravelWorld, 2024). Furthermore, among all the Asia Pacific countries, India is expected to register the highest CAGR of 18.1% from 2024 to 2030 compared to China which is expected to grow at a CAGR of 15.9% (Grand View Research, 2025). In recent years the Indian government has highly invested in promoting ecotourism destinations, specifically the coastal zones through Swadesh Darshan tourism circuits (Ministry of Tourism, Government of India, 2025). Coastal tourism is an important subset of ecotourism. It includes traveling to destinations along the sea and ocean, including beaches, mangroves, coral reefs, and coastal villages. Although these destinations offer unique natural attractions, they are characterized to be ecologically fragile. Due to the fragile coastal ecosystems, the government is emphasizing eco-friendly practices and promoting responsible tourism (Ministry of Ports, Shipping and Waterways, 2024). However, for these initiatives to succeed, the environmental consciousness among tourists becomes imperative.

Despite the extensive literature examining ecotourism satisfaction (Mafi et al., 2020) and tourist engagement behavior in ecotourism context (Paul & Roy, 2025), relatively few studies (Chang & Hsiao, 2025; Naim et al., 2023) have investigated the role of tourists in promoting an ecotourism destination. Notably, Naim et al. (2023) identify the factors that encourage tourists to share green electronic word-of-mouth (e-WOM) in Saudi Arabia. Their findings suggest that green purchase intentions have a positive association with green e-WOM. Likewise, in Taiwan, Chang and Hsiao (2025) demonstrated that it is possible to foster positive attitudes and willingness to engage in low-carbon tourism by reinforcing green perceived value, and strategically leveraging e-WOM. These studies highlight the importance of tourists’ roles in promoting ecotourism destinations through their e-WOM behavior. As one of the key stakeholders in the tourism sector, the contributions of tourists to promoting an environmentally sustainable destination is understudied. Furthermore, a recent study (Jin & Gao, 2025) underscores the growing significance of digital platforms and social media on decision-making and destination marketing in ecotourism. It highlights the need for the integration of digital narratives with ecotourism research to gain deeper insights on consumer behavior and the promotion of sustainable practices in ecotourism. The user-generated online reviews can be instrumental in gaining critical insights into how tourists articulate their experiences of ecotourism destinations. Online reviews are also pivotal in influencing consumers’ behavior and their travel destination choices (Ioannidis & Kontis, 2023; Pooja & Upadhyaya, 2025; Riswanto et al., 2023). Online reviews assist travelers in their search process, generating information about different travel destinations and facilitating many-to-many communication (Abbasi et al., 2023). These reviews are of paramount importance, as they are widely recognized by consumers, and assist them in making informed purchase decisions (Pooja & Upadhyaya, 2024).

In the current study, the researchers focus on examining the online reviews on ecotourism in coastal areas, using coastal Karnataka as the focal region—one of India’s most established tourist destinations since the 1960s, largely celebrated due to its scenic coastline and rich ecological diversity (Chandravanshi, 2020). By offering diverse ecotourism experiences that include snorkeling and aqua sports cites like Devbagh islands, crystalline limestone rock climbing in the Yana caves, or basaltic lava columnar structures in St. Mary’s Island (Rao, 2016), Karnataka holds a prominent position in the Indian tourism sector, ranking third in destination preference among domestic travelers and fifth among foreign tourist arrivals (Chandravanshi, 2020). Thus, the primary objective of the research is to identify emerging and unique themes from the interconnected concepts primarily associated with ecotourism in coastal Karnataka and to explore whether ecotourists consider actively promoting sustainable development and ecological awareness through online reviews.

This study makes notable theoretical and managerial contributions in the domain of ecotourism and consumer behavior. From a theoretical point of view, this would be one of the very few studies that advances the literature on coastal ecotourism by examining user-generated content (UGC) and extracting key experiential themes from their reviews. Furthermore, this study identifies a critical absence of environmental narratives specific to the coastal ecotourism literature and attempts to provide a nuanced explanation for this using the construal level theory (CLT). From a methodological point of view, this study demonstrates the application of Leximancer to analyze large scale online reviews, offering actionable insights to improve the services provided in the tourism sector. Practically, this study demonstrates how destination marketers can strategically analyze consumers’ ecotourism preferences through online reviews. These insights can further help destination marketing organizations (DMOs) to create tailored marketing strategies by bundling several services (guided tours, gastronomic activities, etc.) and enhance their overall experience. It also suggests that DMOs might promote positive experiences for tourists to strengthen their brand credibility. Moreover, to reinforce the sustainable stance of tourism service providers, it is also suggested to train their personnels for immersive on-ground engagement with the tourists, which might help in creating more personalized and culturally authentic ecotourism experiences.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Ecotourism and Coastal Ecotourism

Ecotourism often highlights the responsible utilization of natural resources (M. Das & Chatterjee, 2024). It connects environmental preservation and nature-based tourism experiences through community participation (Ren et al., 2021). Unlike mass tourism, ecotourism embraces a community-oriented approach and prioritizes conservation goals (Fennell, 2020). Tourist experience and satisfaction are central to ecotourism destination marketing strategies (Sana et al., 2023). Ecotourists value a variety of experiences that enhance their connection with nature (Chan & Saikim, 2022), enable community interaction (Alam et al., 2024), provide educational opportunities, foster a sense of responsibility towards the environment (Y. Huang & Liang, 2024; Lengieza et al., 2023), and offer unique recreational activities (Massingham et al., 2019).

Coastal ecotourism is a vital subset of ecotourism that promotes sustainable travel to coastal areas, including beaches, coral reefs, and coastal villages, and emphasizes the conservation of natural environments and the well-being of local communities (Garrod & Wilson, 2004; Ramírez-Guerrero et al., 2025). It aims to provide tourists with an immersive experience in natural settings while promoting environmental and cultural understanding, appreciation, and conservation (Garrod & Wilson, 2004). The uniqueness of marine resources makes coastal tourism attractions different from conventional tourism destinations (Egberts & Hundstad, 2019). Coastal tourism offers immersive experiences through activities such as surfing and diving (J. Liu et al., 2020). In recent years coastal destinations have become highly desired leisure vacation spots because of their rich marine geography and natural resources (Dube et al., 2021). The extensive research (Hu & Chen, 2024; Schlesinger et al., 2020) on tourists’ experiences in coastal destinations highlights that the quality of experience is crucial to this experience-driven sector. Numerous studies have suggested the rising issue of balancing environmental protection and tourist activities in coastal tourism (J. Liu et al., 2020; Papageorgiou, 2016). In recent years many DMOs are increasingly relying on UGC to strategically manage destinations (Zhang et al., 2021). Similarly in coastal tourism, the traveler-generated content plays an essential role in balancing destination marketing strategies with conservation goals. Furthermore, UGC such as online reviews can also be utilized to understand the spectrum of tourist experiences which reflect on the sustainable experiences and ecological awareness (Nowacki & Kowalczyk-Anioł, 2023).

2.2. User-Generated Content and Online Travel Reviews

The digital transformation of the tourism industry has been significantly shaped by the proliferation of social media and UGC. Traditionally reliant on word-of-mouth (WOM), tourism marketing has moved to digitally mediated UGC, namely WOM (Fang et al., 2023), also known as electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) (L. Xia & Bechwati, 2008). eWOM includes voluntarily shared content such as reviews, blogs, and social media posts, and is perceived as authentic and trustworthy information sources for consumer decision-making (Pooja & Upadhyaya, 2024). M. Xia et al. (2009) classify eWOM “many to one” (e.g., number of ratings, downloads calculated by computers), “many to many” (e.g., discussion forums), “one to many” (e.g., text-based product reviews), and “one to one” (instant messaging) contents. Online reviews are an important form of eWOM (Pooja & Upadhyaya, 2025). The online review has a prominent influence on the potential travelers’ future trip-planning (Guo et al., 2021). Tourists without prior experience of the destination frequently use online reviews to gain insights into destinations, accommodations, and experiences (Assaker, 2020; Darwish & Burns, 2019). Furthermore, past research also highlights the growing strategic significance of online reviews for DMOs in enhancing destination image and gaining competitive advantage (Albayrak et al., 2021; Simeon et al., 2017).

In last few years, TripAdvisor®, a popular site for travel reviews, has seen a huge increase in the number of reviews (Statista, 2025). With over 1 billion reviews (Statista, 2025), TripAdvisor® attracts more than 350 million unique monthly visitors (Martin et al., 2020). The TripAdvisor® travel review platform enables a free flow of travel information from real travelers to potential travelers. This unprecedented amount of information on UGC sites is possibly more potent than conventional word-based methods. This not only serves potential tourists and DMOs, but also serves researchers by creating valuable opportunities for knowledge-rich approaches to information access and analysis. For instance, the past literature has also used TripAdvisor® reviews to examine unique themes in online reviews shared by the travelers (Boneta-Ruiz et al., 2025; Nowacki & Kowalczyk-Anioł, 2023) and identified meaningful insights.

While the vast literature examines the role of online reviews in tourism, several areas remain under researched, particularly coastal ecotourism. Past studies have examined whether tourists promote (Nowacki & Kowalczyk-Anioł, 2023) or perceive (Boneta-Ruiz et al., 2025) sustainability values in online reviews. However, limited research exists on how travelers describe environmental or ethical values within reviews, especially in coastal settings. Therefore, the present study examines reviews particularly for coastal tourism and identifies themes formed based on interconnected concepts associated with coastal tourism experiences. This study employs the lens of construal level theory to interpret how these themes are communicated and discusses their underlying perspectives.

2.3. Construal Level Theory

Construal level theory (CLT) posits that the temporal, spatial, social, and hypothetical distance determines whether the individuals interpret experiences in concrete (low-level construal) or abstract (high-level construal) terms (Trope & Liberman, 2010). The low-level construal terms, or concrete interpretation, often explains the “how” of a phenomenon in rich detail, whereas the abstract interpretation offers the “why” in a de-contextualized manner (Trope & Liberman, 2010). The construal level can be considered to be people’s cognition and understanding of the objective world, which constitutes the basis for the evaluation and behavioral outcome of a series of psychologically distant events (Saeed et al., 2024; Yang et al., 2022).

Previously, CLT has been applied in various studies within the realm of marketing, consumer behavior, and tourism domains. Existing tourism studies (Kim et al., 2016; S. Wang & Lehto, 2020) have applied CLT to study the preference for different types of information while traveling to distant destinations. Researchers (B. Liu et al., 2025) also examined the impact of goal framing in cause-related tourism marketing communications on a consumer’s willingness to engage in prosocial behavior through the lens of CLT. Furthermore, the relevance of CLT can also be found in studies examining pro-environmental behavior (Y. Wang & Jiao, 2024), which is environmentally responsible behavior (S. Huang et al., 2025; Xu et al., 2025) in the tourism domain. Numerous studies have also used CLT in the context of climate change research (Fox et al., 2020; Suzuki, 2019) and found psychological distance impacts the environmental behavior. In the present study, CLT offers a conceptual explanation for recognizing when ecotourists’ online reviews emphasize on situational details as opposed to broader ecological values. Therefore, this theoretical perspective allows us to interpret whether the ecotourists consider actively promoting sustainable development and ecological awareness, reflected in the emergent themes identified in the traveler reviews of coastal ecotourism destinations in Karnataka.

3. Research Methods

3.1. Study Setting

The present study focuses on tourists who have engaged in presenting or viewing reviews on TripAdvisor® with a focus on ecotourism locations in India. TripAdvisor® has the most significant number of reviews, mounting up to about 350 million reviews every month, making it a credible platform to retrieve content from. It is the world’s largest travel-related website in 49 markets and 28 languages, with an extensive database of 859 million tourist reviews and opinions of 8.6 million accommodations, restaurants, experiences, airlines, and cruises. This is a relatively inexpensive and easily accessible platform to share experiences and information while creating curiosity, demand, and awareness among potential customers of a tourism destination.

The data used for this study was collected from reviews of 80 lodges and resorts managed by the Jungle Lodges & Resorts, as well as other nature-based resorts and homestays in Coastal Karnataka, India, with a focus on ecotourism locations posted by travelers on the popular online travel review site. Coastal Karnataka in India is a gem with beaches, backwaters, mangroves, and mountains, and it houses butterfly parks, elephant camps, and waterfalls. This provides a perfect setting for the study as they are all nature-based/pure ecotourism locations. Therefore, this study analyzed TripAdvisor® online reviews shared by tourists who visited the 80 ecotourism resorts and homestays in the study region.

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

To determine the sample for data collection, a set of inclusion criteria were established in the initial phase of this study. The first inclusion criteria required the properties to have an active online presence on google as well as TripAdvisor®. Furthermore, the selected properties needed to offer ecotourism activities and demonstrate involvement of the local community in their routine operations. This was verified from each individual website of these properties. As no exhaustive indexed database of lodges was available for coastal Karnataka, the researchers employed purposive sampling technique to collect the data. A manual search was conducted on Karnataka state tourism website, Google, TripAdvisor®, and other booking platforms to compile the list of the eligible properties. Only those properties that met all the inclusion criteria and were actively operating in the region during 2018–2024 were included in this study. In total, 80 such properties were selected and their online reviews were sourced from TripAdvisor®. In total, 1843 reviews posted during 2018–2024 were collected and analyzed. To maintain ethical standards and confidentiality of the reviewers, only textual content was collected and no personal information about the reviewers was extracted. Additionally, to maintain parsimony, no single-word reviews were included in the analysis. The primary purpose of this data collection was to determine how tourists communicate in digital platforms concerning their travel experiences. It is valuable for ecotourism operators to identify and evaluate their performance in key performance areas as highlighted by the tourists in their reviews, and to develop strategies to maximize the tourists’ satisfaction (Cassar et al., 2020; Thomsen & Jeong, 2021).

This study adopted Leximancer (version 4.0) to analyze the data. Leximancer is a widely utilized text-mining tool that conducts qualitative analyses, specifically content analysis, by converting lexical co-occurrence data from natural language into semantic patterns through an unsupervised process involving two extraction stages: semantic and relational (Indulska et al., 2012). Recently, studies have utilized the Leximancer tool to explore consumers’ experiences and opinions (Altun et al., 2025; Byun et al., 2023). It can contribute immensely to the tourism field as a valued tool for examining emerging textual patterns (Goh & Wilk, 2024). Leximancer has the advantage of analyzing a large volume of data and identifying concepts immediately unlike other computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (Byun et al., 2023). Moreover, it operates without any pre-existing assumptions about the meaning of the words, thereby reducing the subjective bias of the researchers (Byun et al., 2023). Although existing research (Engstrom et al., 2022) states that the Leximancer may not identify emotive concepts, the primary objective of the present study is to identify unique themes. Thus, based on the thematic exploration goals of this study, Leximancer was used as the primary tool for data analysis.

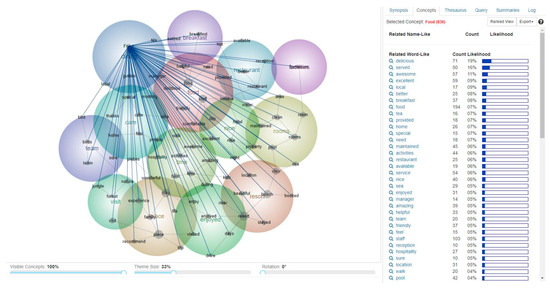

Leximancer software produces “a concept co-occurrence matrix” based on frequency data, and data about the co-occurrence of concepts. Once a concept is produced, the software identifies “a thesaurus of words” closely related to the idea, generating semantic or definitional content (Indulska et al., 2012). The frequent occurrence of a concept is based on a hot map, where the brightness of a concept label and circle reflects its importance, while the size reflects the number of concepts in the text. The strongly related semantical concepts are mapped closely together (Tseng et al., 2015). Conceptual maps display all the ideas of the group relative to the topic at hand and how they are related to each other, and optionally which ideas are more relevant, important, or appropriate. The relative position of the circles, dots, and their distance from each other demonstrates the strength of the semantic links among those concepts in the text, which indicates that when two concepts are close to each other or overlap on the map, they have close semantic links.

4. Results

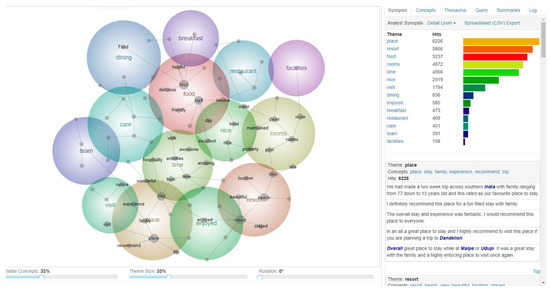

The Leximancer analysis identified ten dominant themes of interlinked concepts (see Figure 1). The five key themes “Place”, “Resort”, “Food”, “Rooms”, and “Time” together captured over half of all the concept hits. The remaining themes were “Nice”, “Visit”, “Dining”, “Enjoyed”, and “Breakfast”. In the Leximancer map (Figure 1), each colored circle represents a theme named after its most-frequent and connected concept. The smaller gray nodes are the concepts, grouped with different rainbow-colored themes. Table 1 describes the theme, hits, and concepts. Theme 1: “Place” was found to be the most prominent one and was represented by the color red (warmer color). The remaining themes followed a descending order of importance, and were identified by orange, yellow, green, blue, and purple. The thematic richness is ascertained by the number of concepts within the theme, with a higher number signifying that the theme has richer meaning. In this study, Leximancer identified a total of 84 concepts.

Figure 1.

Leximancer concept map of online reviews of nature-based resorts and homestays in coastal Karnataka.

Table 1.

Summary of the Leximancer analysis.

The first five themes, “Place”, “Resort”, “Food”, “Rooms”, and “Time”, indicate some of the most prominent and unique aspects of ecotourism offerings and attributes for a nature-based/ecotourist stay. These themes were formed based on interlinked related concepts.

Theme 1: “Place” was most crucial, with 6226 hits. The concepts such as experience, family, stay, time, best, visit, and wonderful were major contributors to the formation of this theme. These concepts reflected tourists’ opinions about the sites or attractions they visited in the region. The strongest association of this theme was with the concept “experience”. It mainly indicated opinions about the experience of the reviewer at the destination. For example, a few of the reviews such as “this place was a great experience,” “wonderful place to visit,” “this place is ideal for family trips” suggested that tourists were more inclined towards having a good and comfortable experience. This finding suggests that within the study region, the reviews are often written on destination experience. Theme 2: “Resort” had 5666 hits. In this theme the concepts such as stayed, view, location, beach, and beautiful were observed. Under this theme, the reviewers prioritized staying at resorts that also offered a positive hedonic experience. The concepts such as view, beautiful, and beach reflect the sensory elements associated within this theme. Theme 3: “Food” received 5237 hits. Concepts such as delicious, staff, service, family, day, and helpful contributed highly to this theme. “Food” was closely associated with terms such as “amazing” and “nice” and emerged as an essential element while making any travel decision due to its fundamental significance. Tourists often rely on online reviews not only to evaluate the overall experience but also to assess the quality of food offered by the accommodation. While food may be considered as the basic requirement, its taste, nutritional value, and overall quality can be critical in shaping tourist satisfaction, and therefore is an essential travel attribute while visiting a destination. Theme 4: “Rooms”, with 4872 hits, was mostly connected to concepts like maintained, clean, property, sea, pool, and view. This theme primarily focuses on the different physical attributes and quality standards of accommodation property. The concepts such as maintained, clean, and property highlight that tourists prioritize evaluating the basic necessities available in the eco stays. Theme 5: “Time”, which received 4566 hits, comprised concepts such as hospitality, wonderful, activities, awesome, amazing, stay, and best. These concepts described the time that the reviewers had at the coastal ecotourism destinations.

Further, theme 6: “Nice”, which had 2919 hits and was deeply associated with concepts such as hotel, excellent, water, service, day, and property, reflects tourists’ general positive assessment of various aspects of their stay. Finally, theme 7: “Visit” received 1794 hits and was the next major theme identified from the analysis. The concepts such as experience and nature contributed to this theme, highlighting tourists’ nature-based experience.

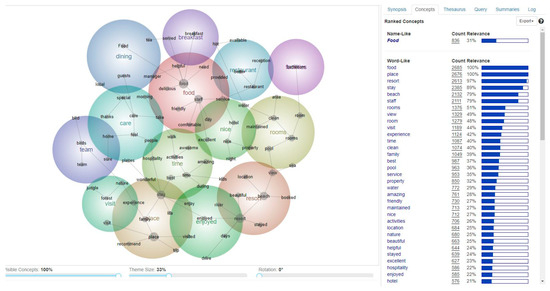

The Leximancer program extracted 84 concepts from 1843 TripAdvisor® reviews. A stemming algorithm was employed to identify the root words to construct an initial thesaurus, from which the list of concepts was subsequently generated. After refining the list, the most relevant concepts were included in the final analysis and are presented. The major concepts were retained after careful evaluation based on their co-occurrence frequency and semantic significance. Name-like concepts and those referring to destinations (e.g., Dandeli and Karwar) were not considered meaningful for assessing tourist experiences. Likewise, some descriptive words about the time of the activities and visit (e.g., ‘during,’ ‘take,’ and ‘time’) and non-informative or ambiguous words were not considered for analysis. Finally, 80 major concepts remained for further analysis (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Leximancer concept frequencies.

As presented in Figure 2, the most prominent concept frequencies (25 percent or higher) were associated with food, place, resort, stay, beach, staff, rooms, view, room, visit, experience, time, clean, family, best, pool, service, property, water, amazing, friendly, maintained, nice, activities, location, nature, and beautiful. It also featured other important concepts pertaining to ecotourism, such as nature, river, birds, forest, jungle, walk, and trips.

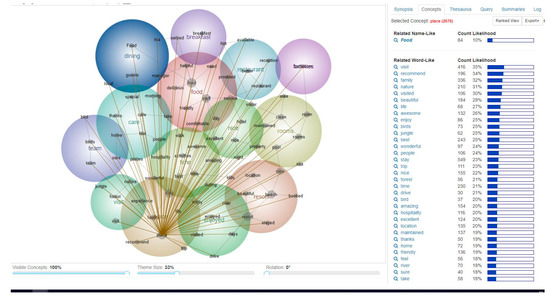

The concept “place”, with 2676 hits, demonstrated strong connections to a range of related words such as visit, recommend, family, nature, visited, beautiful, life, awesome, enjoy, birds, jungle, best, people, wonderful, trip, stay, nice, time, drive, forest, bird, amazing, location, hospitality, forest, excellent, maintained, home friendly feel, and river. Figure 3 illustrates connections associated with “place”. These associations reflect that a tourist’s perception of a destination is formed based on multifaceted attributes ranging from nature-based attributes to suitability for family visits. The concept “place” also has a strong association with other major concepts such as “visit” by highlighting positive evaluation such as place to visit, place to recommend, amazing hospitality and excellent location and well-maintained place with friendly people. The reviews related to this concept also highlight other positive aspects about the richness of nature through words such as beautiful, awesome to enjoy, birds, jungle, and forest.

Figure 3.

Leximancer concept map for “place”.

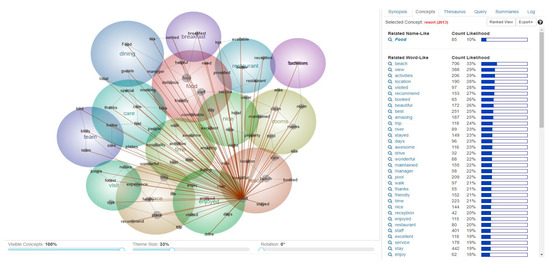

The concept “resort”, which appeared 2613 times, is interconnected with terms such as beach view, activities, location, visited, recommend, booked, beautiful, best, amazing, trip, river, state, days, awesome, dry, wonderful, maintain, manager, pool, walk, friendly, nice reception, enjoyed, restaurant, staff, excellent, service, day, and enjoy (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Leximancer concept map for “resort”.

The interconnectedness of the concepts with these terms suggest that the “resort” could be a beach resort with a view of the sea, offering different activities and with various attractions for tourists who have visited these resorts. These reviews would be useful for potential tourists who are planning to book a stay with an amazing view and that is known for its beauty. Aspects such as river and trip also highlight the proximity between the resorts and the river or trips to the riverside. Furthermore, a few reviews describe the quality of service and professionalism of the staff at the resort. For instance, the following reviews positively evaluate the service quality:

“These resorts are well maintained and they have specified about the managers of these resorts and about the nice friendly staff offering excellent service.”

“Resorts with great reception and restaurants and the tourists have enjoyed their stay in these resort and over all wonderful and an amazing trip.”

The concept “food”, with 836 hits, has interconnectedness with related words such as delicious, served, awesome, excellent, local, better, breakfast, home, special, maintain, activities, restaurant, service, enjoy, friendly, staff, reception, hospitality, location, walk, and pool (see Figure 5). These associations indicate that the concept “food” is fundamental in terms of the quality. These connections also show that the reviewers evaluate the staff that serve food, local cuisine, and specialty cuisines. These concepts also highlight the unique food and gastronomy-related activities at restaurants. This concept is further linked with service, and highlights the positive evaluation of the services offered at the restaurant through words such as amazing, helpful, and friendly staff.

Figure 5.

Leximancer concept map for “food”.

5. Discussion

This study demonstrated that Leximancer effectively generated themes from the tourist reviews extracted from the TripAdvisor® website. The primary objective of the research was to identify unique themes emerging from the interconnected concepts primarily associated with ecotourism in coastal Karnataka. Key themes such as “Place,” “Resort,” “Food,” “Rooms,” and “Time” were identified, and their meaningful relationships with multiple aspects of ecotourism in coastal Karnataka were examined in detail to understand the dimensions of tourist experiences in the region. However, the findings also highlighted the limited vocalization of ecotourism and its tenets in online reviews on nature-based destinations.

Expanding on this finding, the analysis revealed the absence of concepts that are traditionally connected to ecotourism, such as responsible travel, conservation, sustainable use of natural resources, community involvement, or local benefits. Although theme 1, i.e., “Place”, had references to biodiversity, specifically birdwatching, these were more aligned with conventional wildlife tourism rather than coastal ecotourism. For instance, a few reviews described the presence of over 150 bird species and highlighted the area as a “paradise for bird watchers.” Similarly, visitors described encounters with the Malabar Giant Squirrel and other wildlife species. While these statements reflect elements of environmental awareness and appreciation, they are mainly linked to the biodiversity and wildlife of the Western Ghats, rather than the marine or coastal ecosystems vital to coastal ecotourism. However, it should be noted that due to the closer proximity to the Western Ghats, a UNESCO World Heritage biodiversity site, isolating wildlife tourism from coastal tourism poses a conceptual challenge. Consequently, this blurred distinction between wildlife and coastal ecotourism may have led the tourists to associate predominantly with the conservation of forest and wildlife elements, while overlooking coastal tourism elements.

One possible explanation for this oversight is that the tourists may lack awareness and sensitivity, specifically towards coastal ecotourism, in contrast to ecotourism in general. This is in line with the Construal level theory (CLT), which posits individuals mentally associate with issues at varying levels of abstraction based on psychological distance (Trope & Liberman, 2010). Issues perceived as temporally or spatially distant, such as the fragility of marine ecosystem, are interpreted in abstract terms, and may not be given much importance in actions or communications. Consequently, this can be aligned with Markman’s (2018) proposition that individuals tend to disengage from environmental threats perceived as abstract or psychologically distant, and with Luke’s (2020) argument that individuals are less likely to identify with issues that have no direct and immediate relevance to their everyday experiences. Therefore, the lack of explicit and visible references to coastal conservation in reviews represents a construal misalignment and does not reflect insignificance. Tourists may psychologically distance themselves from the coastal ecosystem as an environmental priority, perceiving them as abstract or less personally relevant. This underscores a need for stronger interpretation and promotion of coastal conservation practices at these destinations, to help bridge the psychological gap and encourage more ecotourism narratives in online reviews.

6. Theoretical Contributions and Managerial Implications

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

This study contributes significantly to the literature on ecotourism and coastal ecotourism. First, this study contributes to the growing body of knowledge on the online reviews of ecotourism destinations. The current work addresses important research gaps on identifying major themes from reviews about coastal ecotourism experience and provides meaningful insights. This study highlights that coastal ecotourism is a unique subset of ecotourism and examines the travel reviews of tourists visiting coastal tourism destinations in Karnataka, India. The most critical themes identified based on their occurrence in the reviews were “Place”, “Resort”, “Food”, “Rooms”, and “Time”. These themes highlighted the essential attributes that characterize the trips. The place/destination is the most crucial when any tourist plans a vacation, followed by food, which might be very simple and basic but would be an essential selection criterion for the tourist in making a practical decision. Secondly, the current study identifies the notable absence of environmental narratives specific to coastal ecotourism conservation. Though at first glance this absence might suggest an indifference, through the application of CLT, the study offers a more nuanced interpretation. Conservation of coastal ecotourism destinations may be perceived as spatially or temporally distant; that is, when recalling such contexts, reviewers appear to reflect on a concrete construal level, prioritizing only tangible service cues (fresh seafood, room cleanliness, beach access) and leaving broader ecological narratives (conservation and protection of biodiversity, coastal ecosystem) implicit. By applying CLT, this study attempts to link psychology and tourism marketing, thus offering a nuanced understanding for underrepresented ecotourism experiences in online reviews. In highlighting this mechanism, the study deepens our understanding of underrepresented ecotourism experiences and cautions researchers against equating the absence of environmental keywords with indifference toward conservation.

Finally, this study also contributes to the literature on content analysis’ methodological approaches by employing the Leximancer tool to extract themes from the data. The step-by-step workflow, such as corpus compilation, automated theme extraction, and psychologically informed interpretation, constitutes a robust approach for exploring large-scale digital information in tourism in the future. As online reviews on destinations across the globe are growing significantly, this automated theme extraction and manual interpretation approach equips scholars with a scalable tool to uncover hidden patterns from the tourist reviews.

6.2. Managerial Implications

The insights from this study have multiple implications for ecotourism marketers, practitioners, and policy makers. For ecotourism service providers, online reviews have become imperative to enhance service quality and competitiveness. As travelers rely highly on online reviews during travel planning, platforms like TripAdvisor® serve as real-time feedback systems. Thus, DMOs must invest resources in dedicated online review platform monitoring teams that not only respond to feedback but can also extract actionable insights to improve service delivery and overall guest experience. The service providers can implement textual or sentiment analysis to categorize the recurring themes that provide feedback on both the complaints and praises. They can strategically detect complaints as early warnings and address them proactively before they escalate and harm the brand’s reputation. For example, if a lodge identifies repeated complaints about the ‘food quality’ or ‘limited dining options’ then they can promptly revise their menu and focus more on enhancing their culinary experience.

Additionally, tracking review trends and sentiments can also benefit the tourism service providers to examine the effectiveness of service offerings and to provide tailored offerings to guests based on their specific preferences. They can customize experience bundles that focus on the visitor’s preference. For example, based on the traveler’s past reviews (for instance sustainable dining and nature exploration), properties can curate tourism packages that not only include eco-friendly stays and visits to local heritages, but also combine other activities such as nature tours or sustainable gastronomical experiences.

Furthermore, tourism service providers need to strategically use UGC like online reviews to amplify their ecotourism narratives. Promoting ecotourism narratives through online reviews can help the brands to position themselves in responsible tourism domains and can enhance the credibility of the brand. The tourism operators can educate the travelers on their initiatives towards the conservation of natural resources, engagement with local communities, their cultural sensitivity, and encourage the travelers to reflect these values in their reviews. For example, following a nature trail, the guests can be provided with eco-initiative feedback forms or QR codes to facilitate real-time social media sharing. This would help in generating authentic UGC to raise awareness about their sustainable practices.

Additionally, service providers can equip frontline staff with eco-literacy training to ensure that the sustainable principles and eco-friendly practices are effectively communicated during guest interactions. This might significantly influence the type of content guests generate post-visit. For example, the housekeeping staff can provide verbal cues or handwritten notes about organic food sourcing or wildlife etiquettes, which would reinforce the property’s commitment towards sustainability and wildlife conservation. Finally, the DMOs and tourism service providers can also integrate these reviews in their social media, website advertisements, and brochures to ensure consistent branding. For example, tourism operators based in coastal destinations can convey their association with sustainability and community engagement by promoting guest testimonials with rich socio-cultural experiences. These might include narratives about biodiversity tours featuring exotic marine life or birdwatching excursions. Furthermore, reviews appreciating coastal cuisines prepared by local communities can amplify the property’s commitment towards cultural authenticity and responsible tourism.

7. Limitations, Future Research Directions, and Conclusions

7.1. Limitations

While this study provides valuable insights into UGC in coastal ecotourism, it is not without limitations. One key limitation lies in the use of TripAdvisor® as the data source. Although TripAdvisor® is one of the most popular review platforms, it may omit ecotourism narratives shared in the form of visual or interactive contents on other social media and digital platforms like Instagram, Facebook, YouTube, or blogspace. The younger tech savvy and responsible travelers may engage in information-sharing via these platforms.

Another limitation lies in the use of a dataset that spans over several years. While this study provides a broader perspective on coastal ecotourism, it may be beneficial to focus on more recent data to understand the emerging trends in the domain. Additionally, the Leximancer tool is used to detect concept themes and co-occurrence patterns; it may not effectively capture nuanced textual meanings and sentiments like sarcasm, irony, or deeper layers of emotions. As a result, interpretation of certain concepts can be inherently subjective. Finally, the geographical scope of this study is limited to coastal Karnataka, limiting the generalizability of the findings. The other coastal regions in India or other international destinations may have different ecological features. These differences may impact the visitors’ expectations, which in turn may influence their perceptions and communication of ecotourism concepts. These limitations highlight the need for cautious interpretation.

7.2. Future Research Directions

To address these limitations, several future research avenues are proposed. Firstly, future research should employ different types of data to study UGC. The inclusion of data from other resources like Instagram, YouTube, Google Reviews, or travel forums along with TripAdvisor® reviews might provide more comprehensive insights on coastal ecotourism. In future, comparative studies could also be conducted to investigate different domestic and international coastal ecotourism destinations. This would help researchers and marketers to understand how ecotourism narratives and travelers’ motivations vary geographically.

Also, future research could benefit from using a longitudinal research design that divides data into time periods. Such comparative evaluations conducted before and after the pandemic can reveal how travel priorities and environmental awareness have changed over time. Using qualitative methods like interviews, focus groups, or ethnographic observation together with content analysis could help us better understand tourist experiences and perceptions. Another intriguing area of research is experimental studies that explore how eco-framing interventions like narratives, interactive applications, or signs encourage tourists to generate UGC that promotes conservation. Finally, including the views of community stakeholders, such as local guides, artisans, or conservation workers, would give a more balanced picture of sustainability practices in the destinations.

7.3. Conclusions

The present study examined distinct themes about nature-based resorts and homestays within coastal ecotourism in Karnataka, as extracted from UGC, such as online reviews. Using Leximancer, a text-mining tool, this study identified key themes that tourists emphasize in their online reviews. Although the focus was largely on themes of hospitality like place, food, resort, and rooms, there was a visible absence of references regarding core ecotourism concepts like ecological conservation, community engagement, or sustainability. These findings highlight that conservation values might not be effectively conveyed or understood during the tourist visit, which could lead to a disconnect in online reviews. This study also encourages destination managers, marketers, and policy makers to rethink their interpretive strategies and content engagement practices that connect more deeply and resonate with people to help them understand the principles of ecotourism. In a society that is becoming more digital and ecologically aware, these techniques would make the theoretical and practical contributions of ecotourism research even stronger.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P. and K.P.S.R.; Writing—original draft, S.P. and K.P.S.R.; methodology, S.P.; data curation, K.P.S.R.; formal analysis, S.P. and K.P.S.R.; Visualization, S.P., P.K., and A.M.; Writing—review and editing, P.K. and A.M.; funding acquisition, S.P. and K.P.S.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Indian Council of Social Science Research (grant number 02/2/GN/2021-22/ICSSR/RP/MJ).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abbasi, A. Z., Tsiotsou, R. H., Hussain, K., Rather, R. A., & Ting, D. H. (2023). Investigating the impact of social media images’ value, consumer engagement, and involvement on eWOM of a tourism destination: A transmittal mediation approach. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 71, 103231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A. S. A. F., Begum, H., Bhuiyan, M. A. H., & Sum, S. M. (2024). Community-based development of Fraser’s Hill towards sustainable ecotourism. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 26(1), 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, T., Cengizci, A. D., Caber, M., & Nang Fong, L. H. N. (2021). Big data use in determining competitive position: The case of theme parks in Hong Kong. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 22, 100668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altun, Ö., Saydam, M. B., & Gunay, T. (2025). Unraveling customer experiences in chain coffee shops through online reviews. British Food Journal, 127(6), 1895–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaker, G. (2020). Age and gender differences in online travel reviews and user-generated-content (UGC) adoption: Extending the technology acceptance model (TAM) with credibility theory. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 29(4), 428–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boneta-Ruiz, A., Aramendia-Muneta, M. E., & Gómez-Cámara, I. (2025). From reviews to reality: Tourist perceptions of sustainability in the top 15 global sustainable hotels. Tourism Recreation Research, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, H., Chiu, W., & Won, D. (2023). The voice from users of running applications: An analysis of online reviews using Leximancer. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 18(1), 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassar, M. L., Caruana, A., & Konietzny, J. (2020). Wine and satisfaction with fine dining restaurants: An analysis of tourist experiences from user generated content on TripAdvisor. Journal of Wine Research, 31(2), 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J. K. L., & Saikim, F. H. (2022). Exploring the ecotourism service experience framework using the dimensions of motivation, expectation and ecotourism experience. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 22(4), 425–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandravanshi, R. (2020). A review on coastal tourism in India. Indian Journal of Pure and Applied Biosciences, 8(4), 138–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, I., & Hsiao, Y. (2025). How does environmental cognition promote Low-Carbon travel intentions? the mediating role of green perceived value and the moderating role of electronic Word-of-Mouth. Sustainability, 17(4), 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, A., & Burns, P. (2019). Tourist destination reputation: An empirical definition. Tourism Recreation Research, 44(2), 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D., & Hussain, I. (2016). Does ecotourism affect economic welfare? Evidence from Kaziranga National Park, India. Journal of Ecotourism, 15(3), 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M., & Chatterjee, B. (2015). Ecotourism: A panacea or a predicament? Tourism Management Perspectives, 14, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M., & Chatterjee, B. (2024). Ecotourism in Bhitarkanika Wildlife Sanctuary, India: Assessment of participation, economic benefits and conservation goals. Journal of Ecotourism, 23(4), 589–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinç, A., Bahar, M., & Topsakal, Y. (2023). Ecotourism research: A bibliometric review. Tourism and Management Studies, 19(1), 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, K., Nhamo, G., & Chikodzi, D. (2021). Rising sea level and its implications on coastal tourism development in Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 33, 100346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egberts, L., & Hundstad, D. (2019). Coastal heritage in touristic regional identity narratives: A comparison between the Norwegian region Sørlandet and the Dutch Wadden Sea area. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 25(10), 1073–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engstrom, T., Strong, J., Sullivan, C., & Pole, J. D. (2022). A comparison of Leximancer semi-automated content analysis to manual content analysis: A Healthcare Exemplar using emotive transcripts of COVID-19 hospital staff interactive webcasts. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 21, 16094069221118993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ETTravelWorld. (2024). India’s eco-tourism set for rapid growth by 2027 with market size reaching USD 4.55 billion. The Economic Times–Travel. Available online: https://travel.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/research-and-statistics/research/indias-eco-tourism-set-for-rapid-growth-by-2027-with-market-size-reaching-4-55-billion/113821599 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Fang, S., Li, Y., Zhang, C., & Ye, L. (2023). Speech vs. writing: The influences of WOM communication on tourism experience storytellers. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 54, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennell, D. A. (2020). Ecotourism. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortune Business Insights. (2025). Ecotourism market size, share & industry analysis, by type, traveler type, booking mode, age group, and regional forecast, 2024–2032. Fortune Business Insights. Available online: https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/ecotourism-market-108700 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Fox, J., McKnight, J., Sun, Y., Maung, D., & Crawfis, R. (2020). Using a serious game to communicate risk and minimize psychological distance regarding environmental pollution. Telematics and Informatics, 46, 101320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrod, B., & Wilson, J. C. (2004). Nature on the edge? Marine ecotourism in peripheral coastal areas. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 12(2), 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, E., & Wilk, V. (2024). Showcasing Leximancer in tourism and hospitality research: A review of Leximancer-based research published in tourism and hospitality journals during 2014–2020. Tourism Recreation Research, 49(5), 1005–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grand View Research. (2025). Asia Pacific ecotourism market size & outlook, 2023–2030. Grand View Research. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/horizon/outlook/ecotourism-market/asia-pacific (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Guo, X., Pesonen, J., & Komppula, R. (2021). Comparing online travel review platforms as destination image information agents. Information Technology and Tourism, 23(2), 159–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T., & Chen, H. (2024). Destination experiencescape for coastal tourism: A social network analysis exploration. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 46, 100747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., Shi, L., Sheng, D., He, T., Guo, X., & Xiao, J. (2025). Perceived value, awe, and place attachment: Influencing tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior in desert tourism. Research in Cold and Arid Regions. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., & Liang, P. (2024). What drives ecotourists in China: An exploratory study of ecotourism participants’ significant life experiences. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indulska, M., Hovorka, D. S., & Recker, J. (2012). Quantitative approaches to content analysis: Identifying conceptual drift across publication outlets. European Journal of Information Systems, 21(1), 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, S., & Kontis, A.-P. (2023). Metaverse for tourists and tourism destinations. Information Technology and Tourism, 25(4), 483–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z., & Gao, M. (2025). Global trends in research related to ecotourism: A bibliometric analysis from 2012 to 2022. SAGE Open, 15(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Kim, P. B., Kim, J., & Magnini, V. P. (2016). Application of construal-level theory to promotional strategies in the hotel industry. Journal of Travel Research, 55(3), 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengieza, M. L., Hunt, C. A., & Swim, J. K. (2023). Ecotourism, eudaimonia, and sustainability insights. Journal of Ecotourism, 22(1), 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B., Moyle, B., Kralj, A., Chen, Y., & Li, Y. (2025). Cause-related marketing in tourism: How goal framing promotes consumer prosocial behaviours. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 33(5), 942–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., An, K., & Jang, S. (2020). A model of tourists’ civilized behaviors: Toward sustainable coastal tourism in China. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 16, 100437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, C. (2020). Climate inactivism: Why aren’t people more motivated to address the climate crisis? Earth.Org. Available online: https://earth.org/climate-inactivism-why-arent-people-more-motivated-to-address-the-climate-crisis/ (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Mafi, M., Pratt, S., & Trupp, A. (2020). Determining ecotourism satisfaction attributes—A case study of an ecolodge in Fiji. Journal of Ecotourism, 19(4), 304–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markman, A. (2018). Why people aren’t motivated to address climate change. Harvard Business Review. Available online: https://hbr.org/2018/10/why-people-arent-motivated-to-address-climate-change (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Martin, B. A. S., Jin, H. S., Wang, D., Nguyen, H., Zhan, K., & Wang, Y. X. (2020). The influence of consumer anthropomorphism on attitudes towards artificial intelligence trip advisors. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 44, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massingham, E., Fuller, R. A., & Dean, A. J. (2019). Pathways between contrasting ecotourism experiences and conservation engagement. Biodiversity and Conservation, 28(4), 827–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Ports, Shipping and Waterways. (2024). Lighthouse tourism in India: A beacon of maritime heritage and economic growth. Press Information Bureau, Government of India. Available online: https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=2088359 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Ministry of Tourism, Government of India. (2025). Ministry of tourism annual report 2024–25. Ministry of Tourism, Government of India. Available online: https://tourism.gov.in/sites/default/files/2025-02/Ministry%20of%20Tourism%20Annual%20Report_2024-25_ENGLISH_0.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Naim, A. F. A., Sobaih, A. E. E., & Elshaer, I. A. (2023). Enhancing green electronic word-of-mouth in the Saudi tourism industry: An integration of the ability, motivation, and opportunity and planned behaviour theories. Sustainability, 15(11), 9085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacki, M., & Kowalczyk-Anioł, J. (2023). Experiencing islands: Is sustainability reported in tourists’ online reviews? Journal of Ecotourism, 22(1), 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, M. (2016). Coastal and marine tourism: A challenging factor in Marine Spatial Planning. Ocean & Coastal Management, 129, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, I., & Roy, G. (2025). How eco-service quality affects tourist engagement behaviour in ecotourism: Eco-consciousness and eco activity-based learning and S-O-R Theory. Tourism Recreation Research, 50(2), 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooja, K., & Upadhyaya, P. (2024). What makes an online review credible? A systematic review of the literature and future research directions. Management Review Quarterly, 74(2), 627–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooja, K., & Upadhyaya, P. (2025). Does negative online review matter? An investigation of travel consumers. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 49(2), e70043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Guerrero, G., Fernández-Enríquez, A., Arcila-Garrido, M., & Chica-Ruiz, J. A. (2025). Blue marketing: New perspectives for the responsible tourism development of coastal natural environments. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(3), 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S. (2016). Marketing of resorts & homestays to ecotourists through websites in Coastal Karnataka: A content analysis. Nitte Management Review, 10(1), 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L., Li, J., Li, C., & Dang, P. (2021). Can ecotourism contribute to ecosystem? Evidence from local residents’ ecological behaviors. The Science of the Total Environment, 757, 143814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riswanto, A. L., Kim, S., & Kim, H.-S. (2023). Analyzing online reviews to uncover customer satisfaction factors in Indian cultural tourism destinations. Behavioral Sciences, 13(11), 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M. R., Khan, H., Lee, R., Lockshin, L., Bellman, S., Cohen, J., & Yang, S. (2024). Construal level theory in advertising research: A systematic review and directions for future research. Journal of Business Research, 183, 114870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, A., Jaafar, M., & Mohamad, D. (2020). Strengthening Sustainability: A thematic synthesis of globally published ecotourism frameworks. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 9, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, A., Jaafar, M., Mohamad, D., Ebekozien, A., & Rasul, T. (2024). The multi-stakeholder role in Asian sustainable ecotourism: A systematic review. PSU Research Review, 8(3), 940–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sana, N., Chakraborty, S., Adil, M., & Sadiq, M. (2023). Ecotourism experience: A systematic review and future research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 47(6), 2131–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, W., Cervera-Taulet, A., & Pérez-Cabañero, C. (2020). Exploring the links between destination attributes, quality of service experience and loyalty in emerging Mediterranean destinations. Tourism Management Perspectives, 35, 100699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeon, M. I., Buonincontri, P., Cinquegrani, F., & Martone, A. (2017). Exploring tourists’ cultural experiences in Naples through online reviews. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 8(2), 220–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. (2025). Total number of user reviews and opinions on Tripadvisor worldwide (2014–2022/latest available). Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/684862/tripadvisor-number-of-reviews/ (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Surendran, A., & Sekar, C. (2011). A comparative analysis on the socio-economic welfare of dependents of the Anamalai Tiger Reserve (ATR) in India. Margin the Journal of Applied Economic Research, 5(3), 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S. (2019). Effects of psychological distance on attraction effect. The Journal of Social Psychology, 159(5), 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The International Ecotourism Society. (2015). What is ecotourism: Definition and principles. The International Ecotourism Society. Available online: https://www.ecotourism.org/what-is-ecotourism (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Thomsen, C., & Jeong, M. (2021). An analysis of Airbnb online reviews: User experience in 16 U.S. cities. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 12(1), 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2010). Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychological Review, 117(2), 440–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, C., Wu, B., Morrison, A. M., Zhang, J., & Chen, Y. (2015). Travel blogs on China as a destination image formation agent: A qualitative analysis using Leximancer. Tourism Management, 46, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Tourism. (2025). International tourism recovers pre-pandemic levels in 2024. UN Tourism. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/news/international-tourism-recovers-pre-pandemic-levels-in-2024 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Wang, S., & Lehto, X. (2020). The interplay of travelers’ psychological distance, language abstraction, and message appeal type in social media advertising. Journal of Travel Research, 59(8), 1430–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., & Jiao, Y. (2024). Can environmental science popularization of tourism live streaming stimulate potential tourists’ pro-environmental behavior intentions? A construal level theory analysis. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 60, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L., & Bechwati, N. N. (2008). Word of mouse: The role of cognitive personalization in online consumer reviews. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 9(1), 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M., Huang, Y., Duan, W., & Whinston, A. B. (2009). Ballot box communication in online communities. Communications of the ACM, 52(9), 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., Wang, S., Liu, J., Wang, X. L., & Morgan, N. (2025). How does the cuteness of persuasive communication about sustainable tourism shape tourists’ environmentally responsible behavioral intentions? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L., Fang, X., & Zhu, J. (2022). Citizen environmental behavior from the perspective of psychological distance based on a visual analysis of bibliometrics and scientific knowledge mapping. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 766907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaziz, S. H. S., Gani, A. A., Mahdzar, M., & Rusli, S. A. (2025). Post-pandemic ecotourism in Langkawi: Motivational factors and revisit intentions. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 17(3), 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Gao, J., Cole, S., & Ricci, P. (2021). How the spread of user-generated contents (UGC) shapes international tourism distribution: Using agent-based modeling to inform strategic UGC marketing. Journal of Travel Research, 60(7), 1469–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).