Community-Based Halal Tourism and Information Digitalization: Sustainable Tourism Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Tourism Theory

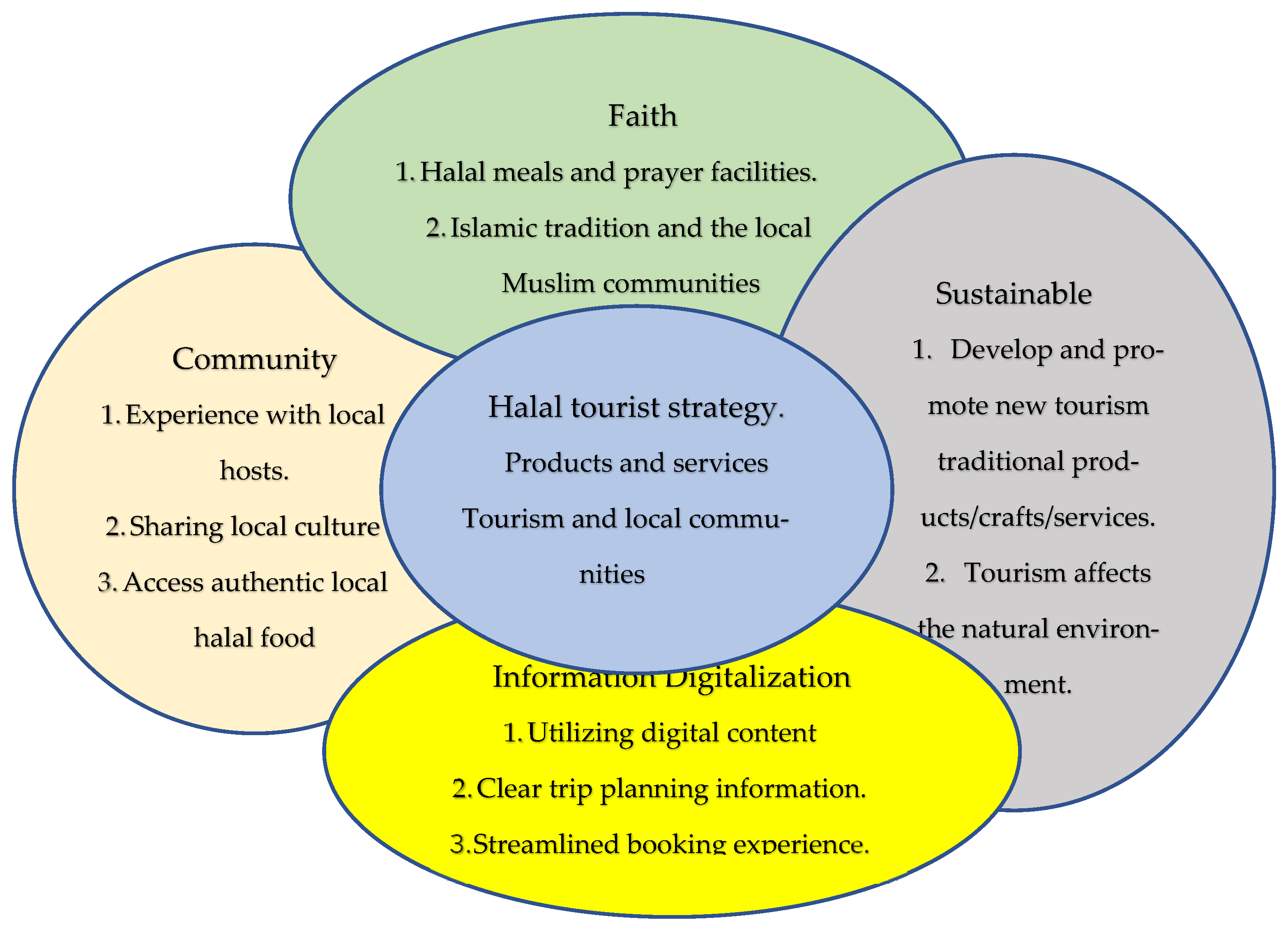

2.2. Sustainable Community-Based Halal Tourism

2.3. Information Digitalization

3. Methods

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Collection Techniques

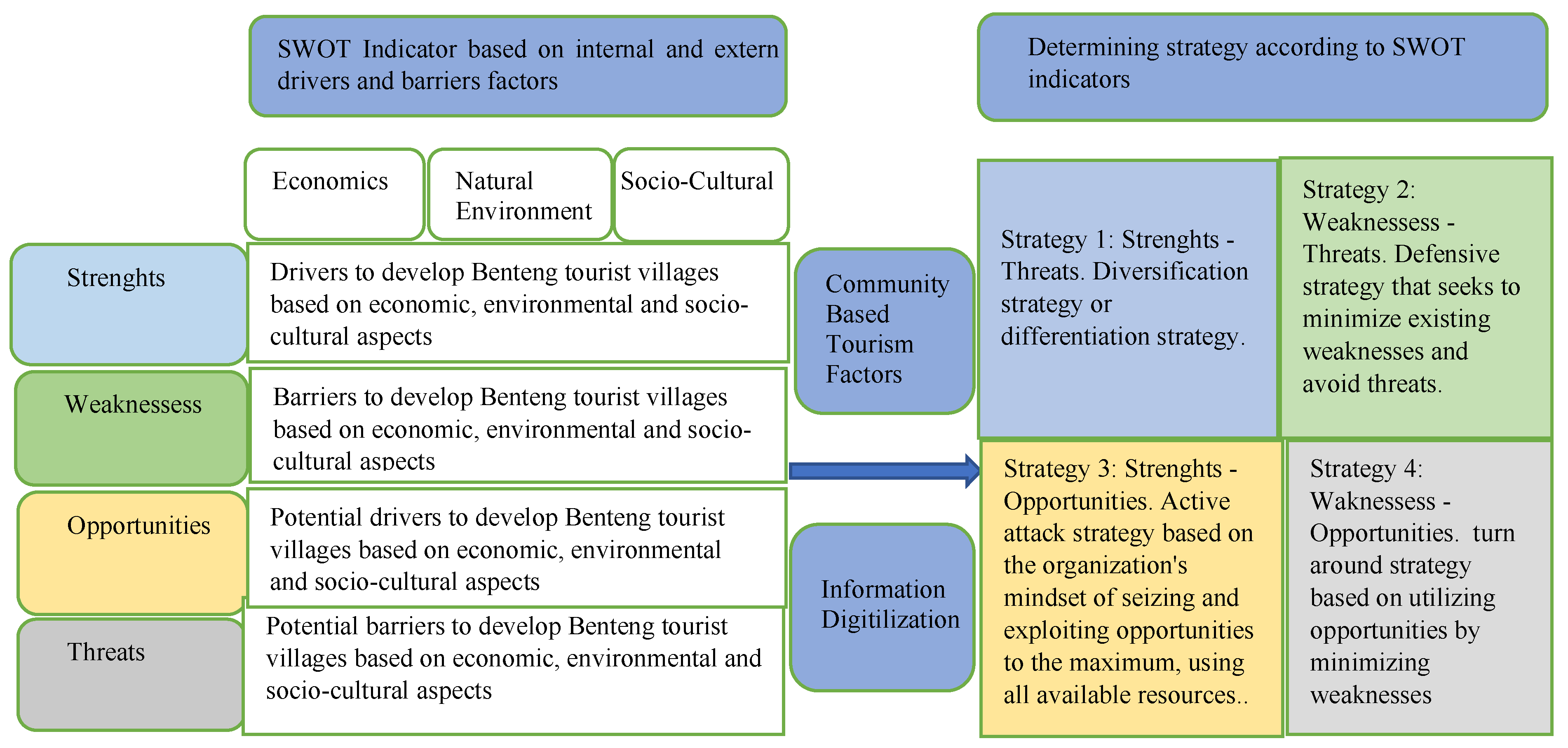

3.3. SWOT Analysis

3.4. Development of Strategies

4. Results

4.1. SWOT Matrix

4.1.1. Strengths

4.1.2. Weaknesses

4.1.3. Opportunities

4.1.4. Threats

4.2. SWOT and I-E Analysis

4.2.1. Strategy 1: Strengths—Threats (Quadrant 2)

4.2.2. Strategy 2: Weaknesses—Threats (Quadrant 4)

4.2.3. Strategy 3: Strengths—Opportunities (Quadrant 1)

4.2.4. Strategy 4: Weakness—Opportunities (Quadrant 3)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Addina, F. N., Santoso, I., & Sucipto. (2020). Concept of halal food development to support halal tourism: A review. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 475(1), 012053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R., Rastogi, S., & Mehrotra, A. (2009). Customers’ perspectives regarding e-banking in an emerging economy. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 16(5), 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M. J., & Akbaba, A. (2020). Halal tourism: Definitional, conceptual and practical ambiguities. Journal of Tourism Research Institute, 1(2), 13–30. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/347934657 (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Alfarizi, M., Ngatindriatun, N., Arifian, R., & Widiharjanti, I. (2025). Green-smart service quality and halal tourism attributes on revisit intention and quality of life: A case study from Indonesia. International Journal of Halal Industry, 1(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalia, F. A., Nova, M., Koh, C., & Suhartanto, D. (2024). Sustainable development in halal tourism industry: The role of innovation and environmental concern. E3S Web of Conferences, 479, 07038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrullah, Kaltum, U., Sondari, M. C., & Pranita, D. (2023). The influence of capability, business innovation, and competitive advantage on a smart sustainable tourism village and its impact on the management performance of tourism villages on Java island. Sustainability, 15(19), 14149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aref, F., Redzuan, M. R., Gill, S. S., & Aref, A. (2010). Assessing the level of community capacity building in tourism development in local communities. Journal of Sustainable Development, 3(1), 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Battour, M., & Ismail, M. N. (2016). Halal tourism: Concepts, practises, challenges and future. Tourism Management Perspectives, 19, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, A., El Sawy, O. A., Pavlou, P. A., & Venkatraman, N. (2013). Digital business strategy: Toward a next generation of insights. MIS Quarterly, 37(2), 471–482. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/43825919 (accessed on 29 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Borodako, K., Berbeka, J., & Rudnicki, M. (2024). Resilience of tourism enterprises facing VUCA environment. In Tourism in a VUCA world: Managing the future of tourism (pp. 157–170). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budarma, I. K. (2024). A model of religiosity integration in sustainable tourism development (The case of Tenganan Pagringsingan Village, Bali, Indonesia). Journal of Applied Sciences in Travel and Hospitality, 7(2), 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A., & Jain, V. (2022). Leveraging digital marketing and integrated marketing communications for brand building in emerging markets. In Marketing communications and brand development in emerging economies volume I: Contemporary and future perspectives (pp. 281–305). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X., Xue, T., Yang, B., & Ma, B. (2023). A digital transformation approach in hospitality and tourism research. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(8), 2944–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chookaew, S., Chanin, O., Charatarawat, J., Sriprasert, P., & Nimpaya, S. (2015). Increasing halal tourism potential at andaman gulf in thailand for muslim country. Journal of Economics, Business and Management, 3(7), 739–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danarta, A., Pradana, M. Y. A., Abror, I., & Yahya, N. E. P. S. (2024). Encouraging religion and sustainable tourism as a conception of Indonesian halal tourism development. Revista de Gestão Social e Ambiental, 18(7), e05920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruyn, C., Said, F. B., Meyer, N., & Soliman, M. (2023). Research in tourism sustainability: A comprehensive bibliometric analysis from 1990 to 2022. Heliyon, 9(8), e18874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devi, A., & Firmansyah, I. (2019). Developing halal travel and halal tourism to promote economic growth: A confirmatory analysis. Journal of Islamic Monetary Economics and Finance, 5(1), 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwiningwarni, S. S., Mardiana, F., & Wahyuningdyah, E. T. (2021, August 1). Tourism village and impact on labor absorption in jombang regency. 2nd International Conference on Business and Management of Technology (ICONBMT 2020) (p. 175), Online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y. K., Ismagilova, E., Hughes, D. L., Carlson, J., Filieri, R., Jacobson, J., Jain, V., Karjaluoto, H., Kefi, H., Krishen, A. S., Kumar, V., Rahman, M. M., Raman, R., Rauschnabel, P. A., Rowley, J., Salo, J., Tran, G. A., & Wang, Y. (2021). Setting the future of digital and social media marketing research: Perspectives and research propositions. International Journal of Information Management, 59, 102168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gohary, H. (2016). Halal tourism, is it really halal? Tourism Management Perspectives, 19, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElMassah, S., & Mohieldin, M. (2020). Digital transformation and localizing the sustainable development goals (SDGs). Ecological Economics, 169, 106490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erul, E., & Woosnam, K. M. (2022). Explaining Residents’ Behavioral Support for Tourism through Two Theoretical Frameworks. Journal of Travel Research, 61(2), 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S., Hughes, M., Hodgkinson, I., & Hughes, P. (2022). Digital transformation of industrial businesses: A dynamic capability approach. Technovation, 113, 102414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginting, N., Revita, I., Santoso, E. B., & Michaela, M. (2024). Sustainable governance traditional village tourism: A study of post revitalisation project in Huta Siallagan Indonesia. Journal of Urban and Regional Analysis, 16(1), 149–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T., Jackson, C., Shaw, S., & Janamian, T. (2016). Achieving research impact through co-creation in community-based health services: Literature review and case study. The Milbank Quarterly, 94(2), 392–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurcan, F., Boztas, G. D., Dalveren, G. G. M., & Derawi, M. (2023). Digital transformation strategies, practices, and trends: A large-scale retrospective study based on machine learning. Sustainability, 15(9), 7496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D., Chi, O. H., Lu, L., & Nunkoo, R. (2019). Consumers acceptance of artificially intelligent (AI) device use in service delivery. International Journal of Information Management, 49, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailuddin, H., Suryatni, M., Yuliadi, I., Canon, S., Syafrudin, S., & Endri, E. (2022). Beach area development strategy as the prime tourism area in indonesia. Journal of Environmental Management and Tourism, 13(2), 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harini, S., Rahmawati, R., Silaningsih, E., Nurhayati, I., Mutmainah, I., Rainanto, B. H., & Endri, E. (2025). Development of halal tourism villages based on local culture and sustainability. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(2), 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryono, J. (2025). The transformation of tourist villages in the digital era: Innovative strategies to enhance tech-based tourism appeal. Side: Scientific Development Journal, 2(3), 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M., & Kaiser, B. N. (2022). Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Social Science & Medicine, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C. K., Lee, C. A., & Chen, Y. N. (2023). The duality determinants of adoption intention in digital transformation implementation. Journal of Organizational and End User Computing (JOEUC), 35(3), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D., Ling Siow, M., & Fabian, H. M. (2024). Community-based tourism in sustainable tourism: Towards a conceptual framework. Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (MJSSH), 9(11), e003107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelfaoui, A., & Rezzaz, M. A. (2021). Revitalization of mountain rural tourism as a tool for sustainable local development in kabylie (Algeria). The case of yakouren municipality. Geojournal of Tourism and Geosites, 34(1), 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoir, M. H. A., & Dirgantara, A. R. (2020). Tourism Village management and development process: Case study of Bandung Tourism Village. ASEAN Journal on Hospitality and Tourism, 18(02), 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B., Kim, S., & King, B. (2020). Religious tourism studies: Evolution, progress, and future prospects. Tourism Recreation Research, 45(2), 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunst, I. (2011). The role of the government in promoting tourism investment in selected Mediterranean countries: Implications for the Republic of Croatia. Tourism and Hospitality Management, 17(1), 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumastuti, H., Pranita, D., Viendyasari, M., Rasul, M. S., & Sarjana, S. (2024). Leveraging local value in a post-smart tourism village to encourage sustainable tourism. Sustainability, 16(2), 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, H. D. L. K., Binotto, E., Padilha, A. C. M., & de Oliveira Hoeckel, P. H. (2023). Cooperation in rural tourism routes: Evidence and insights. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 57, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K. X., Jin, M., & Shi, W. (2018). Tourism as an important impetus to promoting economic growth: A critical review. Tourism Management Perspectives, 26, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liburd, J., Menke, B., & Tomej, K. (2024). Activating socio-cultural values for sustainable tourism development in natural protected areas. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 32(6), 1182–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H., Shi, S., & Gursoy, D. (2022). A look back and a leap forward: A review and synthesis of big data and artificial intelligence literature in hospitality and tourism. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 31(2), 145–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffei, Y., & Hamdi, S. (2022). Synergistic opportunities between the Halal food & tourism sectors to create valuable gastro tourism experiences. Ekonomski Izazovi, 11(22), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejjad, N., Rossi, A., & Pavel, A. B. (2022). The coastal tourism industry in the Mediterranean: A critical review of the socio-economic and environmental pressures & impacts. Tourism Management Perspectives, 44, 101007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G., & Torres-Delgado, A. (2023). Measuring sustainable tourism: A state of the art review of sustainable tourism indicators. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(7), 1483–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P., Singh, U., Pandey, C. M., Mishra, P., & Pandey, G. (2019). Application of student’s t-test, analysis of variance, and covariance. Annals of Cardiac Anaesthesia, 22(4), 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutmainah, I., Yulia, I. A., Setiawan, F. A., Setiawan, A. S., Nurhayati, I., Rainanto, B. H., Harini, S., & Endri, E. (2025). Analysis of factors influencing digital transformation of tourism villages: Evidence from Bogor, Indonesia. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(2), 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasyafira, H. Z., Wiliasih, R., & Nursyamsiah, T. (2023). Development strategy for halal tourism village in Gedepangrango, Sukabumi district. Halal Studies and Society, 1(1), 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarko, J., Ejdys, J., Halicka, K., Magruk, A., Nazarko, Ł., & Skorek, A. (2017). Application of enhanced SWOT analysis in the future-oriented public management of technology. Procedia Engineering, 182, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagot, G., & Andrighetto, N. (2024). Fuel for collective action: A SWOT analysis to identify social barriers and drivers for a local woody biomass supply chain in an Italian alpine valley. Heliyon, 10(19), e38170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickel-Chevalier, S., Bendesa, I. K. G., & Darma Putra, I. N. (2021). The integrated touristic villages: An Indonesian model of sustainable tourism? Tourism Geographies, 23(3), 623–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratiwi, R., Takhim, M., Wardhani, W. N. R., Ragimun, Sonjaya, A., Rahman, A., Basmar, E., & Pambudi, B. (2024). The collaboration of penta helix to develop halal tourism villages in Batang, Cental Java. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning, 19(7), 2753–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, A. R., Haliding, S., Hakim, L., Syafiuddin, & Wahyuddin. (2025). Adaptive strategy for technology-based halal tourism development in Indonesia: Lessons from Singapore’s success. International Journal of Research in Social Science and Humanities (IJRSS), 6(6), 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S. U., Gulzar, R., & Aslam, W. (2022). Developing the integrated marketing communication (IMC) through social media (SM): The modern marketing communication approach. Sage Open, 12(2), 21582440221099936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roblek, V., Meško, M., Bach, M. P., Thorpe, O., & Šprajc, P. (2020). The interaction between Internet, sustainable development, and emergence of society 5.0. Data, 5(3), 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhaeni, N., Yusdiansyah, E., & Aqimuddin, E. A. (2024). Revisiting Indonesia halal tourism policy in light of GATS. Journal of International Trade Law and Policy, 23(2/3), 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samosir, J., Purba, O., Ricardianto, P., Dinda, M., Rafi, S., Sinta, A., Wardhana, A., Anggara, D., Trisanto, F., & Endri, E. (2023). The role of social media marketing and brand equity on e-WOM: Evidence from Indonesia. International Journal of Data and Network Science, 7(2), 609–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawati, R., Eve, J., Syavira, A., Ricardianto, P., Nofrisel, & Endri, E. (2022). The role of information technology in business agility: Systematic literature review. Quality Access to Success, 23(189), 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahnia, C., Permana, D., Harini, S., Endri, E., & Wahyuningsih, M. (2024). The effect of halal awareness, halal certification, and social servicecafe on purchase intention in indonesia: The mediating role of attitude. International Review of Management and Marketing, 14(3), 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suci, A., Junaidi, Nanda, S. T., Kadaryanto, B., & van FC, L. L. (2021). Muslim-friendly assessment tool for hotel: How halal will you serve? Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 30(2), 201–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudirman, S., Mansyur, A. I., Supriadi, Umar, S. H., Sumanto, D., Trimulato, & Syarifuddin. (2023). Sharia tourism business recovery strategies on lombok island indonesia post COVID-19. International Journal of Professional Business Review, 8(7), e02915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukaris, S., & Kirono, I. (2025). Digital transformation for sustainable village tourism. Jurnal Manajerial, 12(01), 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanto, A. B. (2019). The effect of government policy and environmental sustainability on the performance of tourism business competitiveness: Empirical assessment on the reports of international tourism agencies. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy, 9(6), 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada, J. J., Raymond, J., & Punzalan, B. (2012). On the misuse of Slovin’s formula. The Philippine Statistician, 61(1), 129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, A., & Singh, A. (2024). SMEs awareness and preparation for digital transformation: Exploring business opportunities for entrepreneurs in Saudi Arabia’s Ha’il region. Sustainability, 16(9), 3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varelas, S., Karvela, P., & Georgopoulos, N. (2021). The impact of information technology and sustainable strategies in hotel branding, evidence from the Greek environment. Sustainability, 13(15), 8543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbole, A. (2000). Actors, discourses and interfaces of rural tourism development at the local community level in Slovenia: Social and political dimensions of the rural tourism development process. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 8(6), 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, G. (2019). Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 28(2), 118–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., & Cheablam, O. (2025). Sustainable tourism and its environmental and economic impacts: Fresh evidence from major tourism hubs. Sustainability, 17(11), 5058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassler, P., Nguyen, T. H. H., & Schuckert, M. (2019). Social representations and resident attitudes: A multiple-mixed-method approach. Annals of Tourism Research, 78, 102740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessel, L., Baiyere, A., Ologeanu-Taddei, R., Cha, J., & Blegind-Jensen, T. (2021). Unpacking the difference between digital transformation and IT-enabled organizational transformation. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 22(1), 102–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J., Han, L., & Zhang, H. (2022). Exploring driving factors of digital transformation among local governments: Foundations for smart city construction in China. Sustainability, 14(22), 14980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeqiri, A., Ben Youssef, A., & Maherzi Zahar, T. (2025). The role of digital tourism platforms in advancing sustainable development goals in the industry 4.0 era. Sustainability, 17(8), 3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Descriptions | No. of People | Percentage | Descriptions | No. of People | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students | 98 | 48 | 10–19 | 39 | 19 |

| Employees | 32 | 15 | 20–29 | 92 | 46 |

| Entrepreneurs | 39 | 19 | 30–39 | 17 | 9 |

| Housewives | 23 | 11 | 40–49 | 25 | 12 |

| Others | 8 | 5 | 50–59 | 29 | 14 |

| Total | 202 | 100 | 202 | 100 | |

| Male | 66 | 33 | |||

| Female | 136 | 67 |

| Rating | No. of People | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Excellent | 71 | 35 |

| Very Good | 95 | 47 |

| Average | 31 | 15.5 |

| Poor | 2 | 1 |

| Terrible | 3 | 1.5 |

| Total | 202 | 100 |

| Variables | Description | Number of Indicators | Average Value | Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attraction | Everything that can attract tourists to visit tourist areas. Attractions consist of what first attracted tourists to visit. | 17 | 3.235 | Average |

| Accessibility | Components related to the availability of various means of transportation and security contribute to the smooth travel of tourists to ensure their safety | 16 | 3.545 | Average |

| Amenity | Amenities are all kinds of infrastructures and facilities needed by tourists while in a tourist destination | 17 | 2.555 | Poor |

| Ancillary | A component, which is the support provided by the government, destination manager, or local government, to organize tourism activities | 16 | 3.222 | Average |

| Strengths | Rating | Weight | Value | Weaknesses | Rating | Weight | Value |

| The existence of MSMEs’ products | 0.1 | 3 | 0.30 | Low tourist arrival rate | 0.05 | 2 | 0.10 |

| The diversity of agricultural and plantation products | 0.1 | 3 | 0.30 | Pencak Silat attractions have not been playing continuously. | 0.025 | 2 | 0.05 |

| There is a river tubing tourist attraction | 0.1 | 3 | 0.30 | The tour package price is expensive. | 0.05 | 3 | 0.15 |

| The natural beauty and environment | 0.05 | 2 | 0.10 | MSMEs have not been integrated into one area. | 0.05 | 2 | 0.10 |

| The availability and comfortable prayer facilities | 0.05 | 3 | 0.15 | MSME promotion is not yet optimal | 0.05 | 3 | 0.15 |

| Safe from landslides, floods, and earthquakes | 0.05 | 3 | 0.15 | Digital and non-digital promotions have not been carried out massively | 0.05 | 3 | 0.15 |

| There is no difficulty in accessing the internet signals | 0.05 | 3 | 0.15 | The tourism management provides no vehicles to move around the large tourist village area | 0.05 | 3 | 0.15 |

| A local tradition of pencak silat | 0.025 | 2 | 0.05 | Young workers work outside the village | 0.025 | 3 | 0.08 |

| Community and government support | 0.025 | 2 | 0.05 | BTV does not have a cool air temperature | 0.025 | 2 | 0.05 |

| Ethnic and cultural diversity | 0.05 | 2 | 0.10 | Low stakeholder network. | 0.025 | 2 | 0.05 |

| Amount | 0.6 | 1.65 | Amount | 0.4 | 1.03 | ||

| Opportunities | Rating | Weight | Value | Threats | Rating | Weight | Value |

| The trends of village tourist destinations | 0.1 | 3 | 0.30 | The local government does not yet have halal tourism regulations | 0.05 | 3 | 0.15 |

| Increasing public interest in new tourist destinations | 0.05 | 3 | 0.15 | The local government does not yet have an SOP on the edu- and agrotourism | 0.05 | 3 | 0.15 |

| The development of information technology can increase digital promotion. | 0.1 | 3 | 0.30 | Intensive education and training about developing halal village tourism | 0.025 | 3 | 0.08 |

| BTV has a potential natural environment to develop | 0.05 | 3 | 0.15 | Other tourist villages offer similar halal tourism packages | 0.025 | 2 | 0.05 |

| Support from central and local government for the development | 0.05 | 3 | 0.15 | A limited number of companies that can contribute to increasing the potential of the local area | 0.05 | 3 | 0.15 |

| Utilization of external resources | 0.025 | 2 | 0.05 | Village funds that have not been focused on tourism | 0.05 | 2 | 0.10 |

| Availability and affordable transportation modes | 0.1 | 3 | 0.30 | There is a traffic jam on the way to the tourist village | 0.075 | 3 | 0.23 |

| There is no potential for flooding, landslides, or earthquakes | 0.05 | 3 | 0.15 | Competition with other more developed tourist villages | 0.025 | 2 | 0.05 |

| Safe from crime | 0.05 | 3 | 0.15 | A limited number of stakeholders’ contributions | 0.025 | 2 | 0.05 |

| Utilization of CSR to develop a tourism village | 0.025 | 3 | 0.08 | More intensive promotions of other BTV | 0.025 | 2 | 0.05 |

| Amount | 0.6 | 1.78 | Amount | 0.4 | 1.05 |

| Strengths | Weaknesses | |

|---|---|---|

| Threats | Strategy 1 | Strategy 2 |

| Collaborating with the government and local communities in socializing the BTV as halal tourism; Prepare clear guidelines, instructions, and SOPs on sustainable halal tourism; Increase the role of the government in providing financial assistance and training for BTV managers, village officials, MSMEs, farmer groups, and youth organizations; (5). The government must strive to reduce traffic jams. | Conducting halal tourism innovation by increasing the variety of attractions and increasing the synergy of tourism village managers with MSMEs, youth organizations, farmer groups, and other stakeholders. The government must strive to reduce congestion to support increased tourist visits to BTV. | |

| Opportunities | Strategy 3 | Strategy 4 |

| Enhance digital and non-digital promotion of BTV through social media and other channels, increase visitor numbers, foster external cooperation for financial support through Corporate Social Responsibility, and capitalize on the potential tourism resources. | Increasing the variety of attractions is supported by extensive digital promotion, enhancing the synergy among tourism awareness groups, MSMEs, youth organizations, and farmer groups. Determining reasonable and transparent tour package prices, focused on building and infrastructure that support the tourism service industry. Securing free charge of halal certification and other government donations. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nurhayati, I.; Gustiawati, S.; Rofiáh, R.; Pujiastuti, S.; Mutmainah, I.; Rainanto, B.H.; Harini, S.; Endri, E. Community-Based Halal Tourism and Information Digitalization: Sustainable Tourism Analysis. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030148

Nurhayati I, Gustiawati S, Rofiáh R, Pujiastuti S, Mutmainah I, Rainanto BH, Harini S, Endri E. Community-Based Halal Tourism and Information Digitalization: Sustainable Tourism Analysis. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(3):148. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030148

Chicago/Turabian StyleNurhayati, Immas, Syarifah Gustiawati, Rofiáh Rofiáh, Sri Pujiastuti, Isbandriyati Mutmainah, Bambang Hengky Rainanto, Sri Harini, and Endri Endri. 2025. "Community-Based Halal Tourism and Information Digitalization: Sustainable Tourism Analysis" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 3: 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030148

APA StyleNurhayati, I., Gustiawati, S., Rofiáh, R., Pujiastuti, S., Mutmainah, I., Rainanto, B. H., Harini, S., & Endri, E. (2025). Community-Based Halal Tourism and Information Digitalization: Sustainable Tourism Analysis. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(3), 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6030148