Influence of Work Environment Factors on Burnout Syndrome Among Freelancers

Abstract

1. Introduction

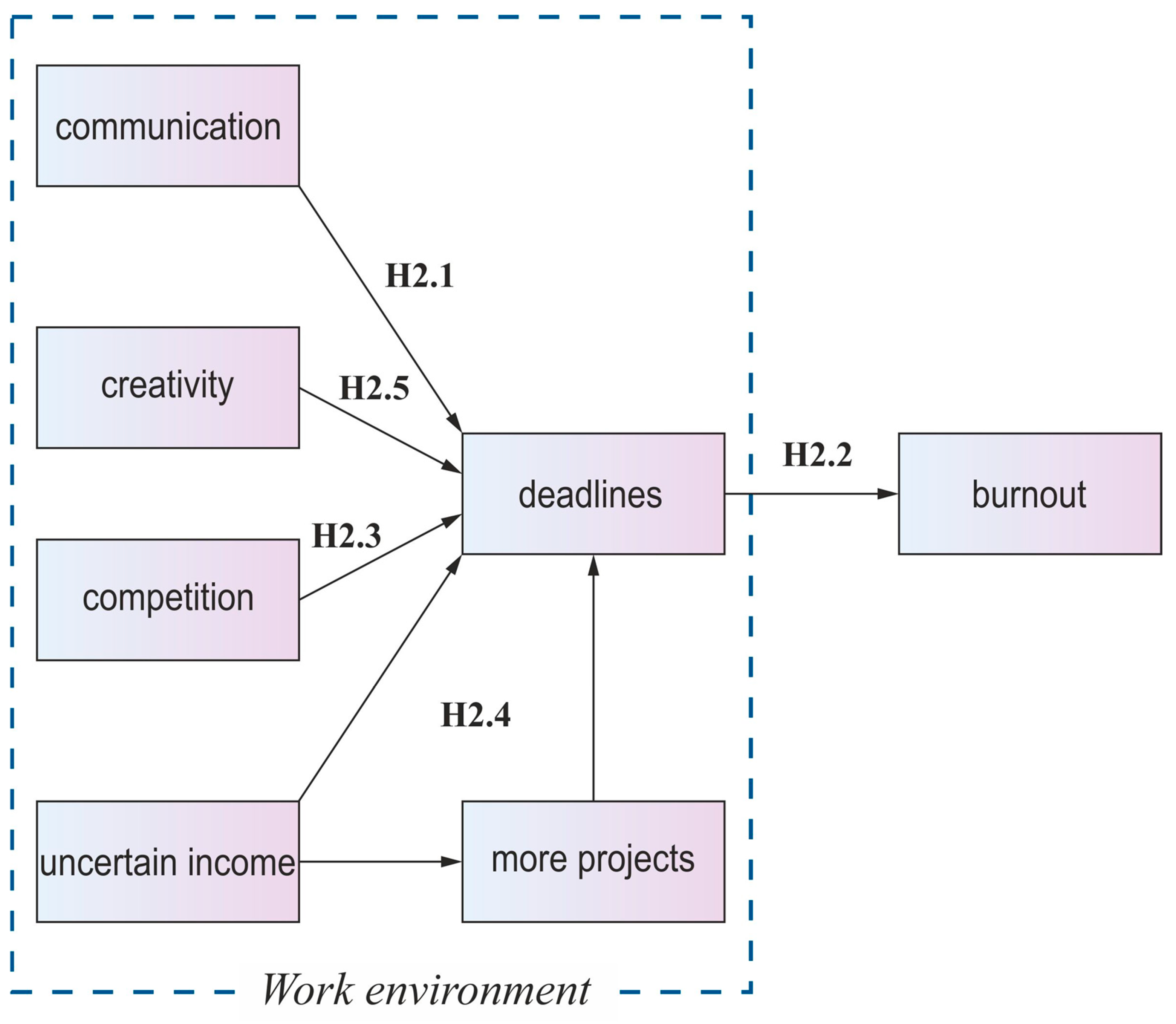

- Uncertain income. Freelancers often face financial instability due to irregular income streams. This lack of predictability can lead to chronic stress and anxiety because there is no guaranteed salary [16,17]. Constant financial uncertainty necessitates continuous efforts to secure new projects, which contributes to a high-stress environment and increases the risk of burnout.

- Short deadlines. Freelancers often face tight deadlines imposed by clients, which can lead to long working hours and increased pressure [27]. This often leads to extended periods of intense work, reducing recovery time and therefore increasing the likelihood of burnout.

- Creativity and innovation requirement. Freelancers must constantly provide creative and innovative solutions to remain competitive, which can be mentally draining [28].

- Offering lower prices. Competitive bidding often forces freelancers to underbid to secure projects, devaluing their labour and increasing financial pressures [29].

- Poor customer communication. Effective communication is critical to a successful implementation. Poor communication leads to misunderstandings and hinders productivity [25].

- Intense competition. The freelance market is highly competitive, requiring constant self-assertion and development [21]. Working in a dynamic and competitive environment often leads to emotional exhaustion.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Maslach Burnout Inventory

2.2.2. Work Environment Factors Questionnaire

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, B.; Wang, L.; Li, B.; Liu, W. Work stress, mental health, and employee performance. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1006580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Arthur, M.B.; Khapova, S.N.; Hall, R.J.; Lord, R.G. Career boundarylessness and career success: A review, integration and guide to future research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 110, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauranges, A. Symptômes et caractéristiques du burn out [Symptoms and characteristics of burnout]. Soins Rev. Réf. Infirm. 2018, 63, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, B.; Xu, M.; Lu, L.; Zhang, X. Burnout syndrome, doctor-patient relationship and family support of pediatric medical staff during a COVID-19 Local outbreak in Shanghai China: A cross-sectional survey study. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1093444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, S.; De Vos, A.; Stuer, D.; Van der Heijden, B.I.J.M. Knowing Me, Knowing You the Importance of Networking for Freelancers’ Careers: Examining the Mediating Role of Need for Relatedness Fulfillment and Employability-Enhancing Competencies. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upwork. Top 10 Benefits and Considerations of Freelancing. Available online: https://www.upwork.com/resources/advantages-of-being-a-freelancer (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Jimenez, A.; Boehne, D.; Taras, V.; Caprar, D. Working across Boundaries: Current and Future Perspectives on Global Virtual Teams Article reference. J. Int. Manag. 2017, 23, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadik, Y.; Bareket-Bojmel, L.; Tziner, A.; Shloker, O. Freelancers: A Manager’s Perspective on the Phenomenon. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2019, 35, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, P.R. Our work-from-anywhere future. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2020, 98, 58. Available online: https://hbr.org/2020/11/our-work-from-anywhere-future (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Rabino, C. The Rise of the Freelance Economy. 2019. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337757836 (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Shagvaliyeva, S.; Yazdanifard, R. Impact of Flexible Working Hours on Work-Life Balance. Am. J. Bus. 2014, 4, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.; Sokas, R.K. The gig economy and contingent work: An occupational health assessment. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 59, e63–e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, S.; Chinta, R. Work–life balance and life satisfaction among the self-employed. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2021, 28, 995–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, C.D.; Marchisio, G.; Morrish, S.C.; Deacon, J.H.; Miles, M.P. Entrepreneurial burnout: Exploring antecedents, dimensions and outcomes. J. Res. Mark. Entrep. 2010, 12, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, U.; Li, J.; Qu, J. A fresh look at self-employment, stress and health: Accounting for self-selection, time and gender. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, 26, 1133–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Zwan, P.; Hessels, J.; Burger, M. Happy free willies? Investigating the relationship between freelancing and subjective well-being. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 55, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vučeković, M.; Avlijaš, G.; Marković, M.R.; Radulović, D.; Dragojević, A.; Marković, D. The relationship between working in the “gig” economy and perceived subjective well-being in Western Balkan countries. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1180532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freelancer Study 2024. The Report About the Present and Future of Freelancing. Available online: https://www.freelancermap.com/files/survey/freelancer-study-2024.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Lee, W.J.; Sok, P.; Mao, S. When and why does competitive psychological climate affect employee engagement and burnout? J. Vocat. Behav. 2022, 139, 103810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunjak, A.; Černe, M.; Nagy, N.; Bruch, H. Job demands and burnout: The multilevel boundary conditions of collective trust and competitive pressure. Hum. Relat. 2023, 76, 657–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.I.; Bunjak, A.; Černe, M.; Fieseler, C. Fostering Creative Performance of Platform Crowdworkers: The Digital Feedback Dilemma. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2021, 25, 263–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Training Foundation. The Future of Work-New Forms of Employment in the Eastern Partnership Countries: Platform Work. Available online: https://www.etf.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2021-07/future_of_work_platform_work_in_eap_countries.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Sutherland, W.; Jarrahi, M.H.; Dunn, M.; Nelson, S.B. Work Precarity and Gig Literacies in Online Freelancing. Work Employ. Soc. 2020, 34, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunjak, A.; Černe, M.; Popovič, A. Absorbed in technology but digitally overloaded: Interplay effects on gig workers’ burnout and creativity. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 103533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhu, W. When do firms benefit from joint price and lead-time competition? Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 302, 497–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubina, I.; Campbell, D.F.J. Creativity Economy and a Crisis of the Economy? Coevolution of Knowledge, Innovation, and Creativity, and of the Knowledge Economy and Knowledge Society. J. Knowl. Econ. 2012, 3, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelia, H.N.; Idris, A.A.; Musa, C.I.; Haeruddin, M.I.M. The influence of work environment and work motivation on employee performance at UPT office. Samsat Bulukumba. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2023, 2, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgia, A.; Bozzon, R.; Digennaro, P.; Mezihorak, P.; Mondon-Navazo, M.; Borghi, P. Hybrid Areas of Work Between Employment and Self-Employment: Emerging Challenges and Future Research Directions. Front. Sociol. 2020, 4, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leighton, P.; McKeown, T. The rise of independent professionals: Their challenge for management. Small Enterp. Res. 2015, 22, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M. How to kill creativity. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 76–186. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual, 2nd ed.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ianakiev, Y. Diagnosis of Burnout Syndrome Among Educational Specialists: Strategies for Coping with Chronic Stress at the Workplace; Paisii Hilendarski University of Plovdiv Publishing House: Plovdiv, Bulgaria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the Fit of Structural Equation Models: Tests of Significance and Descriptive Goodness-of-Fit Measures. Methods Psychol. Res. 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming. Psicothema 2012, 24, 343–344. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 5th ed.; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P.; Maslach, C. Burnout: 35 years of research and practice. Career Dev. Int. 2009, 14, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluschkoff, K.; Hakanen, J.J.; Elovainio, M.; Vänskä, J.; Heponiemi, T. The relative importance of work-related psychosocial factors in physician burnout. Occup. Med. 2022, 72, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roloff, J.; Kirstges, J.; Grund, S.; Klusmann, U. How strongly is personality associated with burnout among teachers? A meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. [CrossRef]

- Lopez, E.; Steiner, A.J.; Smith, K.; Thaler, N.S.; Hardy, D.J.; Levine, A.J.; Al-Kharafi, H.T.; Yamakawa, C.; Goodkin, K. Diagnostic utility of the HIV dementia scale and the international HIV dementia scale in screening for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders among Spanish-speaking adults. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 2017, 24, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Quintana, S.M.; Maxwell S., E. Implications of recent developments in structural equation modeling for counseling psy-chology. Couns. Psychol. 1999, 27, 485–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirom, A. Burnout in Work Organizations. In International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Cooper, C.L., Robertson, I., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.; Enzmann, D. The Burnout Companion to Study and Practice; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Buunk, A.B. Burnout: An Overview of 25 Years of Research and Theorizing. In The Handbook of Work and Health Psychology; Schabracq, M.J., Winnubst, J.A.M., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2003; pp. 383–425. [Google Scholar]

- Zellars, K.L.; Perrewé, P.L. Affective personality and the content of emotional social support: Coping in organizations. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, B.; Hesketh, B. Adaptable behaviours for successful work and career adjustment. Aust. J. Psychol. 2003, 55, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejad, H.G.; Nejad, F.G.; Farahani, T. Adaptability and Workplace Subjective Well-Being: The Effects of Meaning and Purpose on Young Workers in the Workplace. Can. J. Career Dev. 2020, 20, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zheng, Q. Work Stressors and Occupational Health of Young Employees: The Moderating Role of Work Adaptability. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 796710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernet, C.; Gagné, M.; Austin, S. When does quality of relationships with coworkers predict burnout over time? The moderating role of work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 1163–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blyth, D.L.; Jarrahi, M.H.; Lutz, C.; Newlands, G. Self-branding strategies of online freelancers on Upwork. New Media Soc. 2022, 26, 4008–4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.; Olafsen, A.; Ryan, R. Self-Determination Theory in Work Organizations: The State of a Science. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 4, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, N.U.; Raja A., A.; Nosheen, S.; Sajjad, M.F. Dimensions of client satisfaction in web development projects from free-lance marketplaces. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2018, 11, 583–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, Z.; Zhang, J.; Mansoor, R.; Hafeez, S.; Ilmudeen, A. Freelancers as Part-time Employees: Dimensions of FVP and FJS in E- Lancing Platforms. South Asian J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 7, 34–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, D.K.; McDaniel, A.M. A new look at nurse burnout: The effects of environmental uncertainty and social climate. J. Nurs. Adm. 2001, 31, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedeva, N.; Schwartz, S.H.; Van De Vijver, F.J.R.; Plucker, J.; Bushina, E. Domains of Everyday Creativity and Personal Values. Front. Psychol. 2019, 9, 2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, A.; Van der Heijden, B.I.J.M.; Akkermans, J. Sustainable Careers: Towards a conceptual model. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 117, 103196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Presti, A.; Pluviano, S.; Briscoe, J.P. Are freelancers a breed apart? The role of protean and boundaryless career attitudes in employability and career success. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2018, 28, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Burnout | Cronbach α | Standardized α | Number of Items |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional exhaustion | 0.783 | 0.766 | 9 |

| Depersonalization | 0.702 | 0.695 | 5 |

| Reduced personal accomplishment | 0.767 | 0.776 | 8 |

| Total scale reliability | 0.706 | 0.684 | 22 |

| Socio-Demographic Characteristics | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | 20 | 22 | 1.9 |

| 21–30 | 446 | 37.7 | |

| 31–40 | 380 | 32.1 | |

| 41–50 | 244 | 20.6 | |

| over 50 | 91 | 7.7 | |

| Profession/occupation | IT sector | 122 | 10.3 |

| Graphic, fashion, web design | 64 | 5.4 | |

| Administrative activity | 73 | 6.2 | |

| Finance and accounting | 125 | 10.6 | |

| Marketing and advertising | 112 | 9.5 | |

| Education | 122 | 10.3 | |

| Human resources | 43 | 3.6 | |

| Medicine | 133 | 11.2 | |

| Engineering and construction activity | 57 | 4.8 | |

| Law | 48 | 4.1 | |

| Trade and sales | 58 | 4.9 | |

| Journalistic and translation services | 66 | 5.6 | |

| Art | 53 | 4.5 | |

| Consulting services | 53 | 4.5 | |

| Hairdressing and cosmetics | 54 | 4.6 | |

| Gender | Male | 594 | 50.2 |

| Female | 589 | 49.7 | |

| Marital status | Living together | 504 | 42.6 |

| Single | 137 | 11.6 | |

| Family | 101 | 8.5 | |

| Divorced | 441 | 37.2 | |

| Correlation Between | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotional exhaustion | 1 | 0.495 ** | −0.151 * | −0.295 * | 0.009 | −0.034 | −0.079 | 0.181 * | 0.031 | 0.051 | 0.014 |

| 2. Depersonalization | 1 | 0.076 | −0.084 | −0.044 | −0.011 | −0.178 ** | −0.025 | −0.028 | −0.066 | −0.065 | |

| 3. Insecure monthly income | 1 | −0.288 * | 0.178 ** | 0.073 | 0.201 ** | 0.289 ** | −0.070 | −0.175 ** | 0.112 | ||

| 4. Tight deadlines | 1 | −0.007 | 0.113 * | 0.062 | −0.124 * | −0.002 | 0.091 | 0.046 | |||

| 5. Requirement for creativity/originality and innovation | 1 | −0.002 | −0.080 | 0.037 | −0.007 | 0.049 | 0.280 ** | ||||

| 6. Offering lower (more attractive) prices | 1 | 0.197 ** | 0.044 | 0.062 | −0.057 | 0.031 | |||||

| 7. Poor customer communication | 1 | 0.045 | −0.025 | −0.033 | −0.015 | ||||||

| 8. High competition | 1 | −0.076 | −0.123 * | 0.012 | |||||||

| 9. Lack of an opportunity to take vacation | 1 | 0.261 ** | 0.071 | ||||||||

| 10. Insufficient time for family and oneself | 1 | 0.118 * | |||||||||

| 11. Lack of regular working hours and workplace | 1 | ||||||||||

| Mean () | 19.40 | 18.01 | 1.49 | 1.70 | 1.91 | 1.78 | 1.84 | 1.76 | 1.78 | 1.64 | 1.87 |

| Std. Deviation | 4.213 | 4.365 | 0.501 | 0.457 | 0.290 | 0.413 | 0.371 | 0.426 | 0.417 | 0.479 | 0.339 |

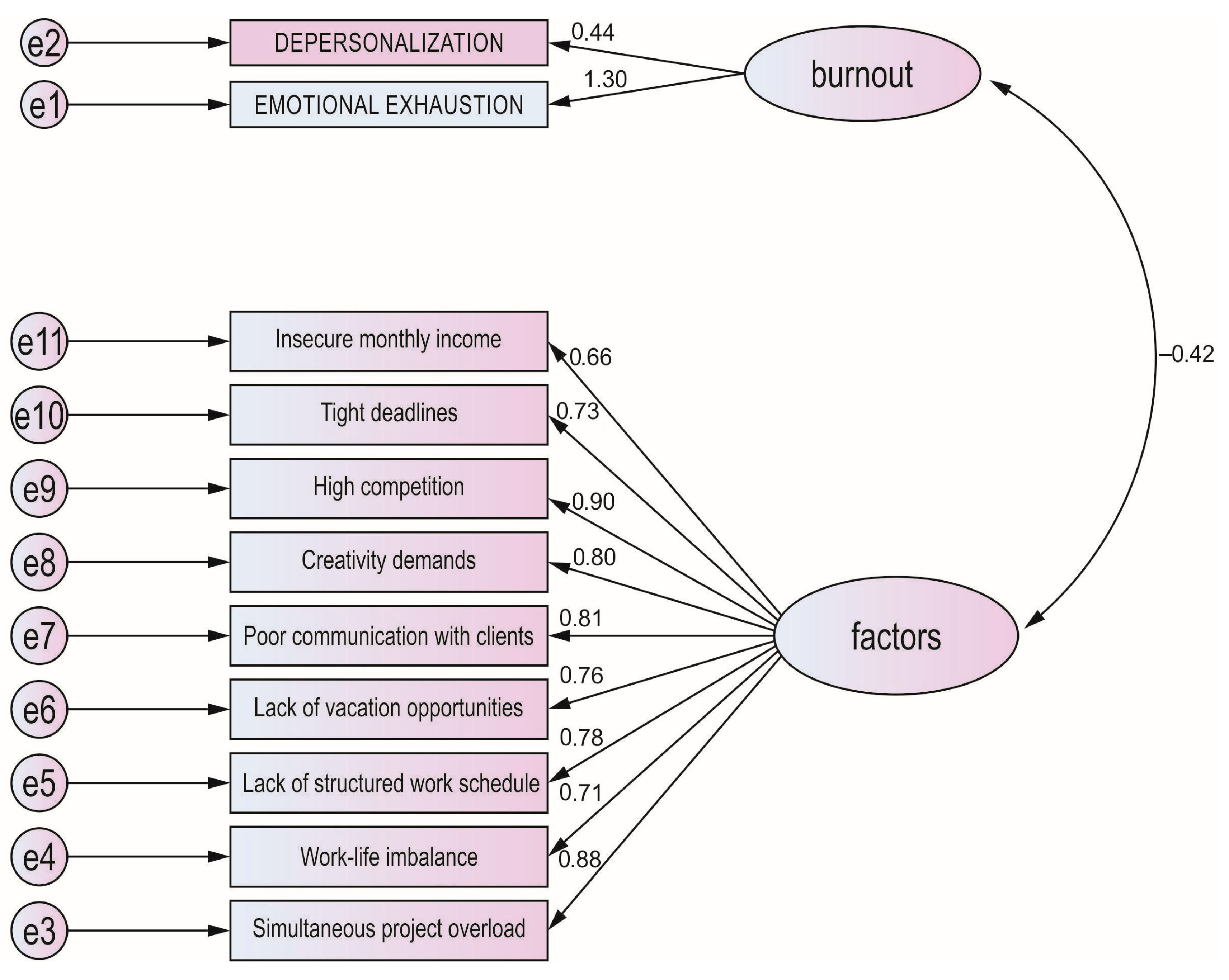

| Fit Measure | Good Fit | Acceptable Fit | Obtained Values Two-Factor Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | 476.1 | ||

| df | 43 | ||

| P | 0.000 | ||

| RMSEA | 0 < RMSEA < 0.05 | 0.05 < RMSEA < 0.08 | 0.082 |

| NFI | 0.95 < NFI < 1.00 | 0.90 < NFI < 0.95 | 0.942 |

| CFI | 0.97 < CFI < 1.00 | 0.95 < CFI < 0.97 | 0.947 |

| GFI | 0.95 < GFI < 1.00 | 0.90 < GFI < 0.95 | 0.929 |

| AGFI | 0.90 < AGFI < 1.00 | 0.85 < AGFI < 0.90 | 0.891 |

| Factors | Standardized Estimators | Standard Error | Z-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insecure monthly income | 0.66 | 0.01 | 66 | *** |

| Tight deadlines | 0.73 | 0.019 | 38.42 | *** |

| Requirement for creativity/originality and innovation | 0.9 | 0.017 | 52.94 | *** |

| Offering lower (more attractive) prices | 0.8 | 0.017 | 47.06 | *** |

| Poor customer communication | 0.81 | 0.016 | 50.63 | *** |

| High competition | 0.76 | 0.006 | 126.67 | *** |

| Lack of an opportunity to take vacation | 0.78 | 0.012 | 65 | *** |

| Insufficient time for family and oneself | 0.71 | 0.018 | 39.44 | *** |

| Lack of regular working hours and workplace | 0.88 | 0.009 | 97.78 | *** |

| Emotional exhaustion | 1.3 | 0.005 | 260 | *** |

| Depersonalization | 0.44 | 0.015 | 29.33 | *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ianakiev, Y.; Medneva, T. Influence of Work Environment Factors on Burnout Syndrome Among Freelancers. Psychiatry Int. 2025, 6, 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030095

Ianakiev Y, Medneva T. Influence of Work Environment Factors on Burnout Syndrome Among Freelancers. Psychiatry International. 2025; 6(3):95. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030095

Chicago/Turabian StyleIanakiev, Youri, and Teodora Medneva. 2025. "Influence of Work Environment Factors on Burnout Syndrome Among Freelancers" Psychiatry International 6, no. 3: 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030095

APA StyleIanakiev, Y., & Medneva, T. (2025). Influence of Work Environment Factors on Burnout Syndrome Among Freelancers. Psychiatry International, 6(3), 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychiatryint6030095