How Deutsche Welle Shapes Knowledge and Behaviour of Syrian Diaspora

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. News Media and Crisis Reporting

2.2. Knowledge and News Media Exposure

2.3. News Media and Audience Behaviour

2.4. Framing the Syrian Conflict in Global Media

3. Theoretical Framework

4. Methodology

4.1. Study Design

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Sampling and Respondent Recruitment

4.4. Data Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Media Consumption Patterns

5.2. Perceptions of DW’s Coverage

5.3. Knowledge Enhancement

5.4. Behavioural Impacts

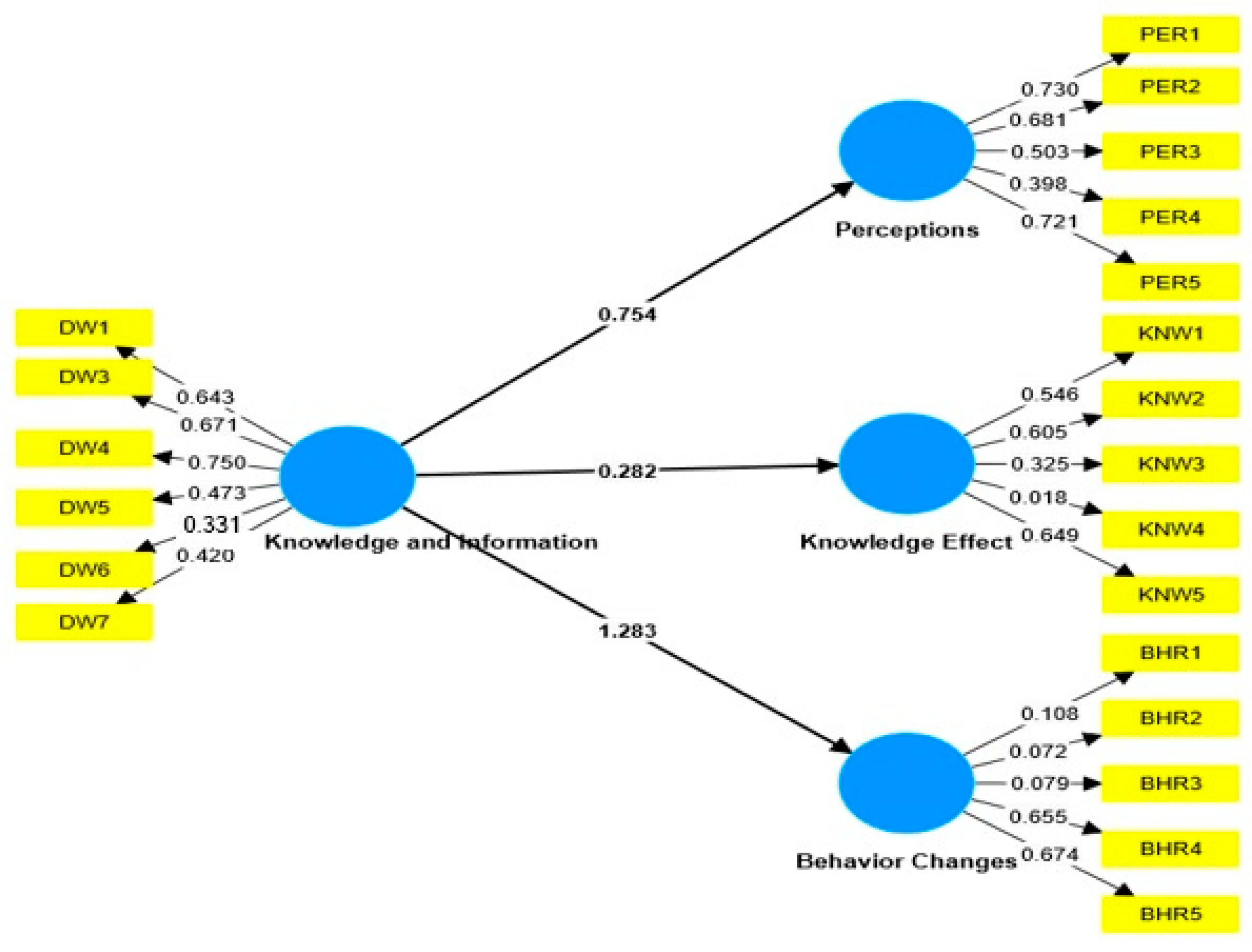

5.5. SEM Analysis

Measurement Model Evaluation

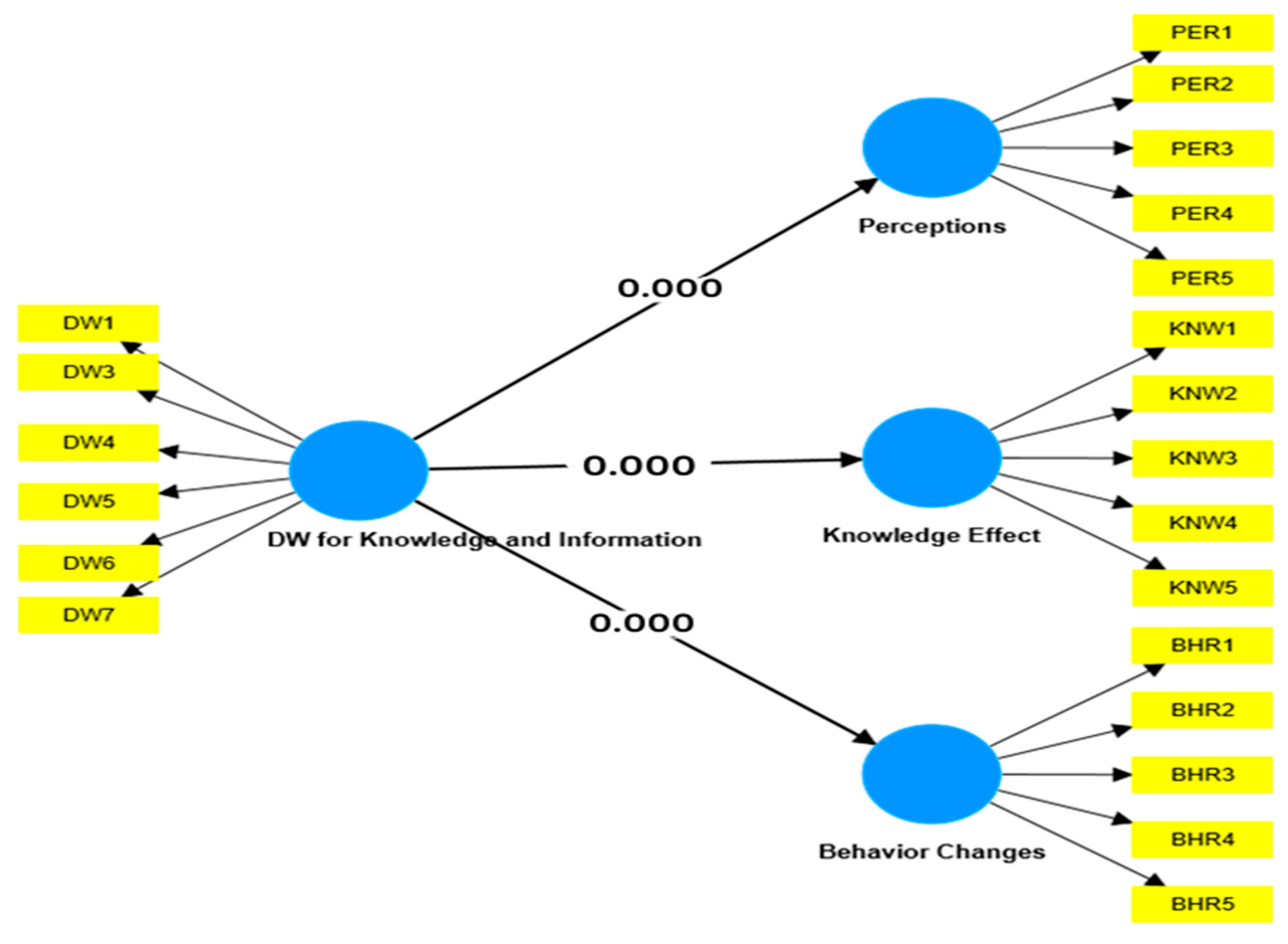

5.6. Structural Model Assessment

6. Conclusions

6.1. Implications

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abroms, L. C., & Maibach, E. W. (2008). The effectiveness of mass communication to change public behavior. Annual Review of Public Health, 29(1), 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jaber, K., & Elareshi, M. (2014). The future of news media in the Arab world. Lambert Academic Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- AlHamad, A. (2020). Predicting the intention to use mobile learning: A hybrid SEM-machine learning approach. International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology, 9(3), 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Husein, N., & Wagner, N. (2023). Determinants of intended return migration among refugees: A comparison of Syrian refugees in Germany and Turkey. International Migration Review, 57(4), 1771–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.-K. K., & Gower, K. K. (2009). How do the news media frame crises? A content analysis of crisis news coverage. Public Relations Review, 35(2), 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbin, S. (2021). Recontextualizing constructive journalism in contemporary China: A comparative and intercultural perspective. Social Sciences in China, 42(2), 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apuke, O. D., & Omar, B. (2020). Fake news proliferation in Nigeria: Consequences, motivations, and prevention through awareness strategies. Humanities and Social Sciences Reviews, 8(2), 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardèvol-Abreu, A. (2015). Framing theory in communication research: Origins, development and current situation in Spain. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 70, 423–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, O. G., Georgiou, M., & Harindranath, R. (2007). Transnational lives and the media: Re-imagining diasporas. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balla, E. (2023). The European Union’s response to the Syrian refugee crisis. In Y. Stivahtis, & S. Max (Eds.), Policy and politics of the Syrian refugee crisis in Eastern Mediterranean states. E-International Relations. [Google Scholar]

- Blach-Ørsten, M., Jönsson, A. M., Jóhannsdóttir, V., & GuðmundssonI, B. (2023). The role of journalism in a time of national crisis: Examining criticism and consensus in Denmark, Iceland, and Sweden during the COVID-19 pandemic. In B. Johansson, Ø. Ihlen, J. Lindholm, & M. Blach-Ørsten (Eds.), Communicating a pandemic: Crisis management and COVID-19 in the Nordic countries (pp. 261–282). Nordicom. [Google Scholar]

- Bruine de Bruin, W., Saw, H.-W., & Goldman, D. P. (2020). Political polarization in US residents’ COVID-19 risk perceptions, policy preferences, and protective behaviors. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 61(2), 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A., & Zhang, X. (2022). Changing social representations and agenda interactions of gene editing after crises: A network agenda-setting study on Chinese social media. Social Science Computer Review, 40(5), 1133–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K., Babaeianjelodar, M., Shi, Y., Janmohamed, K., Sarkar, R., Weber, I., Davidson, T., De Choudhury, M., Huang, J., Yadav, S., KhudaBukhsh, A., Bauch, C. T., Nakov, P., Papakyriakopoulos, O., Saha, K., Khoshnood, K., & Kumar, N. (2023). Partisan US news media representations of Syrian refugees. In Y.-R. Lin, M. Cha, & D. Quercia (Eds.), Proceedings of the international AAAI conference on web and social media (pp. 103–113). AAAI Press, Palo Alt. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chib, A., & Ang, M. W. (2023). Dispositions of dis/trust: Fourth-wave mobile communication for a world in flux. New Media & Society, 25(4), 776–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J. (2016). Why do people use news differently on SNSs? An investigation of the role of motivations, media repertoires, and technology cluster on citizens’ news-related activities. Computers in Human Behavior, 54, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, G., Blumell, L., & Bunce, M. (2021). Beyond the ‘refugee crisis’: How the UK news media represent asylum seekers across national boundaries. International Communication Gazette, 83(3), 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czymara, C. S., & Klingeren, M. v. (2022). New perspective? Comparing frame occurrence in online and traditional news media reporting on Europe’s “Migration Crisis”. Communications, 47(1), 136–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Hoog, N., & Verboon, P. (2020). Is the news making us unhappy? The influence of daily news exposure on emotional states. British Journal of Psychology, 111(2), 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deutsche Welle. (2024). Germany’s Syrian community—Facts and figures. Deutsche Welle. Available online: https://www.dw.com/en/germanys-syrian-community/a-71007863 (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Eisele, O., Litvyak, O., Brändle, V. K., Balluff, P., Fischeneder, A., Sotirakou, C., Syed Ali, P., & Boomgaarden, H. G. (2022). An emotional rally: Exploring commenters’ responses to online news coverage of the COVID-19 crisis in Austria. Digital Journalism, 10(6), 952–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elareshi, M., Alsridi, H., & Ziani, A. (2020). Perceptions of online academics’ and Al-Jazeera.net’s news coverage of the Egyptian political transformation 2013–2014. Jurnal Komunikasi: Malaysian Journal of Communication, 36(1), 124–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elareshi, M., Habes, M., Ali, S., & Ziani, A. (2021). Using online platforms for political communication in Bahrain election campaigns. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 29(3), 2013–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- el-Nawawy, M., & Elmasry, M. H. (2024). Worthy and unworthy refugees: Framing the Ukrainian and Syrian refugee crises in elite American newspapers. Journalism Practice, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, S. (2013). Women and journalism. I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou, J. M. (2013). Diaspora in the digital era: Minorities and media representation. Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe, 12(4), 80–99. Available online: https://heinonline.org/hol-cgi-bin/get_pdf.cgi?handle=hein.journals/jemie2013§ion=26 (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Green, M., King, E., & Fischer, F. (2021). Acculturation, social support and mental health outcomes among Syrian refugees in Germany. Journal of Refugee Studies, 34(2), 2421–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happer, C., & Philo, G. (2013). The role of the media in the construction of public belief and social change. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 1(1), 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasibuan, E. J., Sahputra, D., & Mazdalifah, M. (2022). The presence of television media in disaster reporting to increase the community’s disaster literacy skills. Jurnal Komunikasi Ikatan Sarjana Komunikasi Indonesia, 7(1), 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawdon, J., Hawdon, J., Oksanen, A., Hawdon, J., Oksanen, A., & Räsänen, P. (2012). Media coverage and solidarity after tragedies: The reporting of school shootings in two nations. Comparative Sociology, 11(6), 845–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie Chan, T., Han, J., Roslan, S. N., & Wok, S. (2022). Predictions of Netflix binge-watching behaviour among university students during movement control order. Journal of Communication, Language and Culture, 2(2), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogiannidis, S., Chatzitheodoridis, F., Papaevangelou, O., & Nikolaou, E. E. (2023). An empirical study on the role of media in crisis communication management in uncertain times. Journal of Logistics, Informatics and Service Science, 10(1), 321–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, K. H., & Al-Rawi, A. (2018). Diaspora and media in Europe: Migration, identity, and integration. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E., Blumler, J. G., & Gurevitch, M. (1973). Uses and gratifications research. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 37(4), 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, E., Nordø, Å. D., & Iversen, M. H. (2023). How rally round-the-flag effects shape trust in the news media: Evidence from panel waves before and during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. Political Communication, 40(2), 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozman, C., Tabbara, R., & Melki, J. (2021). The role of media and communication in reducing uncertainty during the Syria war. Media and Communication, 9(4), 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, L.-Y., Hew, T.-S., Ooi, K.-B., Lee, V.-H., & Hew, J.-J. (2019). A hybrid SEM-neural network analysis of social media addiction. Expert Systems with Applications, 133, 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, S. (2013). The potential and limitations of Twitter activism: Mapping the 2011 Libyan uprising. Journal for a Global Sustainable Information Society, 11(1), 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miladi, N. (2006). Satellite TV news and the Arab diaspora in Britain: Comparing Al-Jazeera, the BBC and CNN. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 32(6), 947–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, J., van de Velde, R. N., Merten, L., & Puschmann, C. (2020). Explaining online news engagement based on browsing behavior: Creatures of habit? Social Science Computer Review, 38(5), 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, A., Ameen, M., & Baloch, R. B. (2024). From screens to surveys: Exploring Pakistan’s smog crisis through media analysis and healthcare perspectives. Human Nature Journal of Social Sciences, 5(2), 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutono, A., & Dagada, R. (2016). An investigation of mobile learning readiness for post-school education and training in South Africa using the technology acceptance model. International Journal of Education and Research, 4(9), 353–366. [Google Scholar]

- Nanz, A., & Matthes, J. (2020). Learning from incidental exposure to political information in online environments. Journal of Communication, 70(6), 769–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, N. D. C. (2023). We don’t belong to the same war: A comparative analysis of media coverage in Germany on the Syrian and Ukrainian war [Master’s thesis, Departamento de História, Iscte University Institute of Lisbon]. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick, I. (2024). News frames emotion: Analyzing how audience are influenced by news frames. American Journal of Arts, Social and Humanity Studies, 3(1), 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreault, M. F., & Perreault, G. P. (2021). Journalists on COVID-19 journalism: Communication ecology of pandemic reporting. American Behavioral Scientist, 65(7), 976–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, S. D. (2007). The framing project: A bridging model for media research revisited. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, P., & Atanasova, D. (2016). A report on the role of the media in the information flows that emerge during crisis situations. Modelling of dependencies and cascading effects for emergency management in crisis situations, 33. Available online: https://casceff.eu/media2/2017/02/D3.4-Media-in-the-information-flows-during-crisis-situation.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Riad, A., Drobov, A., Krobot, M., Antalová, N., Alkasaby, M. A., Peřina, A., & Koščík, M. (2022). Mental health burden of the Russian–Ukrainian War 2022 (RUW-22): Anxiety and depression levels among young adults in Central Europe. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(14), 8418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rönkkö, M., & Cho, E. (2020). An updated guideline for assessing discriminant validity. Organizational Research Methods, 25(1), 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, T. E. (2007). Uses and gratifications theory in the 21st century. In Refining milestone mass communications theories for the 21st century (pp. 36–70). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvarajah, S., & Fiorito, L. (2023). Media, public opinion, and the ICC in the Russia–Ukraine war. Journalism and Media, 4(3), 760–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorbjørnsrud, K., & Figenschou, T. U. (2022). The alarmed citizen: Fear, mistrust, and alternative media. Journalism Practice, 16(5), 1018–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsagris, M., & Pandis, N. (2021). Normality test: Is it really necessary? American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, 159(4), 548–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Aelst, P., Toth, F., Castro, L., Štětka, V., Vreese, C. d., Aalberg, T., Cardenal, A. S., Corbu, N., Esser, F., Hopmann, D. N., Koc-Michalska, K., Matthes, J., Schemer, C., Sheafer, T., Splendore, S., Stanyer, J., Stępińska, A., Strömbäck, J., & Theocharis, Y. (2021). Does a crisis change news habits? A comparative study of the effects of COVID-19 on news media use in 17 European countries. Digital Journalism, 9(9), 1208–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Nordheim, G., Müller, H., & Scheppe, M. (2019). Young, free and biased: A comparison of mainstream and right-wing media coverage of the 2015–16 refugee crisis in German newspapers. Journal of Alternative & Community Media, 4(1), 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyastuti, D. A. R. (2021). Using new media and social media in disaster communication. Komunikator, 13(2), 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., & Maitland, C. (2016, June 3–6). Communication behaviors when displaced: A case study of Za’atari Syrian refugee camp. Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development (pp. 1–4), Ann Arbor, MI, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziani, A., Elareshi, M., & Al-Jaber, K. (2017). News media exposure and political communication among Libyan elites at the time of war. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 8(1), 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Item | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 127 | 61.4% |

| Female | 80 | 38.6% | |

| Age | 18–20 | 22 | 10.6% |

| 21–30 | 72 | 34.8% | |

| 31–40 | 37 | 17.9% | |

| 41–50 | 24 | 11.6% | |

| 51 or above | 52 | 25.1% | |

| Educational Level | High school | 72 | 34.9% |

| College | 69 | 33.4% | |

| Bachelor’s degree or more | 66 | 31.9% | |

| Occupation | University student | 19 | 9.2% |

| Unemployed | 57 | 27.5% | |

| Freelance | 95 | 45.9% | |

| Receive national aid | 36 | 17.4% | |

| Residing in Germany | 1 year or less | 41 | 19.8% |

| 2–3 years | 27 | 13.0% | |

| 4–6 years | 83 | 40.1% | |

| 7–9 years | 38 | 18.4% | |

| 10 years and more | 18 | 8.7% |

| Construct | Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test | Shapiro–Wilk Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Sig. | Statistic | Sig. | |

| DW’s news coverage | 0.639 | 0.143 | 0.388 | 0.301 |

| Perceptions | 0.633 | 0.124 | 0.112 | 0.108 |

| Knowledge | 0.509 | 0.491 | 0.353 | 0.637 |

| Behavioural changes | 0.635 | 0.191 | 0.346 | 0.425 |

| Construct | Code | Item | Source | Loadings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DW’s news coverage AVE = 0.528 CA = 0.727 CR = 0.812 | DW1 | I seek news about the Syrian crisis through the DW channel | (Bruine de Bruin et al., 2020) | 0.610 |

| DW2 | I follow news on the DW channel | 0.432 | ||

| DW3 | I perceive DW as my primary source | 0.983 | ||

| DW4 | I often watch news programmes to stay informed about global events | 0.946 | ||

| DW5 | DW provide more reliable information on the Syrian crisis | 0.665 | ||

| DW6 | I often turn to DW for comprehensive coverage of international conflicts | 0.875 | ||

| DW7 | I trust DW to deliver accurate and objective news on the Syrian crisis | 0.726 | ||

| Perceptions AVE = 0.524 CA = 0.773 CR = 0.845 | PER1 | DW provides an in-depth analysis of the Syrian crisis | (Anbin, 2021; Knudsen et al., 2023) | 0.817 |

| PER2 | DW provides objective coverage of the Syrian crisis | 0.738 | ||

| PER3 | DW’s coverage of the Syrian crisis is unbiased | 0.869 | ||

| PER4 | DW provides credible coverage of the Syrian crisis | 0.660 | ||

| PER5 | DW’s coverage of the Syrian crisis is superior | 0.555 | ||

| Knowledge AVE = 0.538 CA = 0.718 CR = 0.745 | KNW1 | Watching DW increases my awareness of key events in the Syrian crisis | (de Hoog & Verboon, 2020; Nanz & Matthes, 2020) | 0.875 |

| KNW2 | DW’s reporting gives me a deeper understanding of the Syrian crisis | 0.917 | ||

| KNW3 | DW’s coverage helps me understand the history of the Syrian crisis | 0.845 | ||

| KNW4 | I feel more knowledgeable about the humanitarian aspects of the Syrian crisis | 0.864 | ||

| KNW5 | DW improves my ability to discuss the Syrian crisis with others | 0.845 | ||

| Behavioural changes AVE = 0.581 CA = 0.742 CR = 0.814 | BHR1 | I often share DW’s news coverage about the Syrian crisis on social media | (Möller et al., 2020; Mutono & Dagada, 2016) | 0.808 |

| BHR2 | Watching DW leads me to participate in discussions about the Syrian crisis | 0.773 | ||

| BHR3 | My opinions about the Syrian crisis have changed after watching DW | 0.670 | ||

| BHR4 | Watching DW motivates me to support humanitarian efforts for Syria | 0.983 | ||

| BHR5 | I prefer DW for news on other global issues because it covers the Syrian crisis | 0.946 |

| Construct | Fornell–Larcker Criterion | Hetreotrait–Monotrait Ratio Scale | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 1. DW’s news coverage | 0.655 | |||||||

| 2. Perceptions | 0.581 | 0.724 | 0.081 | |||||

| 3. Knowledge | 0.198 | 0.244 | 0.325 | 0.257 | 0.26 | |||

| 4. Behavioural changes | 0.288 | 0.189 | 0.383 | 0.546 | 0.205 | 0.498 | 0.489 | |

| Construct | R2 | F2 |

|---|---|---|

| Perceptions | 0.338 | 0.510 |

| Knowledge | 0.437 | 0.241 |

| Behavioural changes | 0.774 | 3.421 |

| Hypotheses | β | t-Value | p-Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DW’s coverage => Perceptions | 0.754 | 10.999 | 0.000 | Accept |

| DW’s coverage => Knowledge | 0.282 | 7.420 | 0.000 | Accept |

| DW’s coverage => Behavioural changes | 1.283 | 15.206 | 0.000 | Accept |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qudah, M.; Murad, H.A.; Habes, M.; Elareshi, M. How Deutsche Welle Shapes Knowledge and Behaviour of Syrian Diaspora. Journal. Media 2025, 6, 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6020092

Qudah M, Murad HA, Habes M, Elareshi M. How Deutsche Welle Shapes Knowledge and Behaviour of Syrian Diaspora. Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(2):92. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6020092

Chicago/Turabian StyleQudah, Mohammad, Husain A. Murad, Mohammed Habes, and Mokhtar Elareshi. 2025. "How Deutsche Welle Shapes Knowledge and Behaviour of Syrian Diaspora" Journalism and Media 6, no. 2: 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6020092

APA StyleQudah, M., Murad, H. A., Habes, M., & Elareshi, M. (2025). How Deutsche Welle Shapes Knowledge and Behaviour of Syrian Diaspora. Journalism and Media, 6(2), 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6020092