Abstract

Latvia after the collapse of the Soviet Union regained its independence in 1991. Since then, many political and social reforms have been introduced, minority education among them. Latvia began gradually abandoning the use of minority languages as mediums of instruction and switching to teaching exclusively in Latvian as the sole state language. This caused protests by minority groups, especially by Russians—the largest minority group in Latvia. The article examines 77 online news articles by Latvian, Russian, and European media covering protests against minority education reform in Latvia between 2004 and 2024. Each news article used at least one photograph/video of placard(s) with written information from the protests. The aim of the article is to understand how different media represent the linguistic landscape of protests against minority education reform and what are the main discourses they create and maintain regarding to the linguistic landscape of such protests in Latvia. The description of the linguistic landscapes shows three main trends: (1) only journalists (most often anonymous) describe the written information expressed at the protests, (2) emphasis is on the number of placard holders at the protests, their age and affiliation with minority support organizations and political parties, (3) author(s) quote individual slogans, more often demonstrated from one protest to another, without disclosing in which language they were originally written and what problems (within and behind the language education) they highlight or conceal. The main narratives that are reinforced through the descriptions of the linguistic landscapes included in the articles are two: (1) the Russian community is united and persistent in the fight against the ethnolinguistically unjust education policy pursued by the government, and (2) students, parents, and the Russian community should have the right to choose which educational program to study at school.

1. Introduction

In Latvia, education reform, along with citizenship policy and language policy, is one of three state policy sectors that, after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the regaining independence in 1991, were directly aimed at regulating the conditions of ethnic/linguistic minorities and limiting their social and political opportunities (Boguševiča, 2009, p. 8). The introduced minority education reform meant gradual abondance of the use of minority languages as mediums of instruction (MOI) and switching to teaching exclusively in the Latvian language, legally defined as the only state (“official”) language. The government justified its political course in education through national goal to increase the competitiveness of non-Latvian children by helping them obtain higher education and enter the labor market. However, it was the education reform that provoked the most massive and intense protests in the history of independent Latvia (Boguševiča, 2009, p. 8; Burr et al., 2025, p. 435).

Although the Russian-speaking minority in the newly formed nation-state was characterized by lower political participation activity, less social capital, and weaker use of social networks, compared to Latvians (e.g., Linden, 2008), according to information compiled by Boguševiča (2009, p. 91), the first protests of the Russian-speaking minority against the education reform at different times and with different numbers of participants took place as early as 2001, with the largest number of participants gathering in 23 May 2003 (10,000 in total, although the scholar indicates that the number varies depending on news source).

The minority school reform in 2003 and 2004 was widely covered in Latvian traditional media and their digital counterparts. Maksimovtsova’s (2019) about discourses in Post-Soviet Russian-language digital media in the Baltic states shows that the Russian-language version of the news website Delfi (ru.delfi.lv) in these two years hosted extremely heated discussion on the reform mainly sharing the arguments in favor of Russian. The most frequently spread argument against the reform was the argument of equality and protection of Russian-speakers’ rights followed by the economic argument (‘we pay taxes’) and the argument of Latvia as a ‘defective democracy’. Some arguments for the Latvian language were the argument of better economic opportunities, the argument of the ‘existential’ threat to Latvian, and the integration argument (Maksimovtsova, 2019, pp. 312, 314, 321–322).

Later the media portrayal of minority education reform has not been among the nationally widely studied research topics. For instance, the reform was not addressed in the studies “Language” in 2007 and 2008 by Baltic Institute of Social Sciences and regular language situation monitoring in 2011, 2016, and 2021 by Latvian Language Agency. Of particular note is the publication “Language Situation in Latvia, 2010–2015” (2016) which contains the chapter “Representation of the Most Significant Events in Language Policy in the Mass Media” (Liepa, 2016a) without touching on the minority education reform and the protests that took place during the period under review. Therefore, logically, written texts displayed in protests against minority education reform have similarly gone unnoticed by researchers. Yet these texts are essential elements of temporary linguistic landscapes in city and (re-)creators of public discourses both in physical and digital spaces.

The Linguistic landscape (LL) covers all written texts in public or semi-public spaces. LL research traditionally includes sociolinguistic analysis of such texts in the context of language policy, language vitality, language contacts, and ethnic composition; however, its rapid development shows great expansion of interdisciplinary approaches and themes (e.g., Gorter & Cenoz, 2023; Kallen, 2023). Printed and hand-made written texts (e.g., logos, slogans, statements, requests, and poems), oral announcements and audio (e.g., anthems, popular songs) in protests, strikes, demonstrations, and processions constitute the so-called mobile LLs. In contrast to stable, more permanent LLs, the mobile LL emphasizes the meeting of text authors and readers and their participation in public discourse. The importance of both discourse participant groups (i.e., authors and/or presenters and readers) is highlighted by Kallen: “What makes a text bearing object part of the LL (and not simply a piece of metal with words and images on it) is its role in discourse between a sign instigator and a sign viewer” (Kallen, 2023, p. 27). However, although LL texts in protests are ephemeral and non-fixed in nature they are typically photographed/filmed, then published and discussed in the online, thus becoming a part of wider discourses over social problems lightened by protests and the use of language in protests. Considering the inherently mobile nature of protest signs, Sebba (2010, pp. 73–75) calls them “discourses in transit”.

Despite the tendency of protests to be perceived in light of psycho-emotional aspects and scandalousness, LL scholars have paid little attention to media coverage of protest signage as well (one known exception is Pošeiko, 2016b). Therefore, the article intends to examine online media articles that include both LL texts from protests and provide a description or analysis of such texts. The article aims to identify and characterize ways how national and international online media in Latvian, Russian, and English portray the LL of protests against minority education reform in Latvia and what are the main discourses they create and maintain regarding to the LL of the protests.

Following the introduction, the Section 2 presents a compressed literature review. The Section 3 is dedicated to the contexts of protest formation in Latvia. The Section 4 describes the research data and methodology. The Section 5 presents the results of the content analysis of excerpts from online news articles about protests and photographs with protest placards. In the Section 6, the results of the study are discussed in relation to the goal of the article.

2. Literature Review

In the LL research bibliography database (Gorter, 2013), which as of 24 January 2024, consisted of records of 1456 conference papers, individual articles, edited books, and teaching materials, 48 records contained the word protest in their title, abstract, and/or in keywords. A closer look reveals three important features. First, the study of protests is based on semiotic (especially geosemiotics and multimodality) analysis (e.g., Al-Naimat, 2020; Urribarrí, 2022). Second, one of the main focuses in the analysis of protests is participants’ identity(ies) and the representation of belonging to a particular community (e.g., Ben-Said & Kasanga, 2016; Milani, 2015). Third, researchers’ attention has been linked to protests against acute political and social problems, and the language of protest has been perceived as one of the forms of communication, one of the ways to discuss these problems and express opinions and attitudes towards them (e.g., Hanauer, 2015; Martín Rojo, 2014). Protests against the (non-)use of language(s) or changes in language policy have not received researchers’ attention so far. The only known exception is an article on the use of the letter k in the Spanish LL and public objections related to this language conflict (Screti, 2015).

The most extensive study of the LLs in Latvia, Pošeiko’s (2015) PhD thesis about the language situation in the Linguistic landscapes of the cities in the Baltic states, mentions ephemeral or temporary LLs and non-fixed or moving LL texts (e.g., stickers on cars and advertisements on trams) but does not analyze them. Another example is an article about “EuroPride 2015” in Riga, the capital of Latvia, that discusses the semiotic landscape (including LL texts) of the International Pride Parade in 2015 (Pošeiko, 2016a). Inspecting galleries of photos and videos published in national news portals, the author analyzes the form, content, and language of demonstration placards, clothing, and accessories.

In turn, research on minority education reform in Latvia has mentioned protests mainly because of their scale and intensity and the involvement of the Russians as the largest minority community, with almost no attention paid to the LL of the protests (e.g., Hogan-Brun, 2007; Lazdiņa & Marten, 2021; Silova, 2006). For instance, describing government’s initiated social changes through education and its proposed idea about the teaching 60 per cent of all subjects in Latvian at the secondary school level (grades 10 to 12) (see more below Section 3.4.2), Vihalemm and Hogan-Brun (2013, p. 60) state that “the rigid and non-inclusive manner in which this change was handled produced large-scale mass protests that involved more than half of the minority secondary school pupils”.

Since “language in the public space […] can serve as a mechanism for resisting, protesting against and negotiating de facto language policies” Shohamy (2006, p. 129), language conflicts at the social level are an important dimension of understanding the LL of protests. The term language conflict is mostly perceived as conflict resting on differences or oppositions of interests of people in relation to linguistic phenomena (language structural elements, language use, status, prestige, and attitudes), their awareness of the differences and, finally, actions regarding the differences or oppositions (Burr et al., 2025, p. 430). Building on Darquennes’s (2015) and Wingender’s (2021) models for studying language conflicts, Burr et al. (2025) develop a framework for studying interactions between language conflict and LL. According to it, LL can be involved in language conflicts in three ways, as (1) an object of, a stimulus for, conflict, (2) a tool or means by which conflict is conducted, or (3) an outcome of conflict (Burr et al., 2025, p. 438). The LL of protests against education reform in Latvia is seen as a tool by which conflict is articulated in the public space (Burr et al., 2025, p. 435).

We can conclude that protests concerning language-related issues and media coverage of such protests are unexplored research strands in LL studies. This article, with its focus on the representation of the LL of protests against language-in-education in news websites, seeks to partially fill this gap.

To better understand the organization, content, and language of protests in Latvia, the next section briefly introduces: (1) legal requirements for organizing protests, (2) ethnolinguistic and sociolinguistic context, (3) languages of instruction in general education, and (4) language policy, in general, and changes in language education policy, in particular.

3. The Legal and Sociolinguistic Contexts of Language Protests

3.1. LL in Protests

The law “On Meetings, Processions, and Pickets” (Likumi, 1997) defines two protest forms—a procession and a picket—to express individual’s or group’s ideas and opinions in a public space using posters, slogans, and banners. There are two differences between these forms: the first involves movement on the roads, streets, squares, pavements, or other territories designed for traffic and may include speeches and public addresses, while the second is a static gathering of people in a public space but during which no speeches or public addresses are made.

There are two things to consider when creating and demonstrating LL in protests in Latvia. First, in protests, it is forbidden: (1) to turn against independence of the Republic of Latvia and its territorial integrity, to make proposals on forcible change of the state structure of Latvia, and to encourage to disobey the laws, and (2) to propagate violence, hate, Nazism, or communism ideology (Likumi, 1997). Second, in protests, there is freedom of speech and linguistic freedom (Likumi, 1997). The latter means that, unlike static, more permanent LL texts, placards can be written in any language and/or script.

3.2. Ethnolinguistic and Sociolinguistic Context

Census data taken in the territory of Latvia at different times represent the diversity of the society. Along with Latvians, in varying proportions, Russians, Belarusians, Ukrainians, Germans, Poles, Lithuanians, and other numerically less represented ethnic communities live here (Veģis, 2021, 2022a, 2022b, 2022c). Currently, the largest ethnic minority community is Russians (24.4% of the total population of the country), the next numerically largest minorities (Ukrainians and Belarusians) reach the 3% mark (PMLP, 2022).

The results of the last census in 2011 (Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia, 2016) show that the most frequently used languages at home are Latvian (56.26% of the total population of the country), Russian (33.75%), Lithuanian (0.1%), Polish and Ukrainian (both 0.08%), another language (0.33%, including Latgalian, a language spoken mainly in Eastern Latvia). Latvian as the state language covers all sociolinguistic domains (particularly, in government, public service, and education) while Russian is mainly used in public informal communication (e.g., on the street or in a store) and in work with colleagues, customers, and cooperation partners (Kļava & Rozenvalode, 2021, p. 89).

Sixty-one percent of residents between 18 to 34 with a mother tongue other than Latvian rate their Latvian language skills as good or very good (Kļava & Kopoloveca, 2021, pp. 59–60). In turn, an in-depth analysis of the results of the centralized exams of 9th grade (between 14 and 16 years old) pupils in 2023 shows that pupils who studied the minority program in the previous school year (respectively 2022/2023) obtained almost 17% lower results in the Latvian language exam than those who studied in Latvian language programs (the average performance in Latvian was 60%) (VISC, 2023).

3.3. Languages of Instruction in General Education

Until the 1990s, there were two separate school systems in Latvia in terms of content, language of instruction, and duration of instruction. They were called “Latvian schools” and “Russian schools,” which contributed to the societal segregation of ethnic Latvians and Russians (including other ethnic minorities who usually attended Russian schools). For instance, in 1989, there were 205 schools in Soviet Latvia with Russian as MOI (Apine & Volkovs, 2007, p. 51), in which Latvian was a compulsory subject, but teaching in this subject was formal and ineffective (Dorodnova, 2003, p. 16).

Since the 1990s, education reforms have therefore aimed to slowly integrate minority schools into the main education system. Minority schooling in Latvia is predominantly aimed at the Russian speaking population, and there are schools for Ukrainians, Poles, and other minorities, which are often supported from abroad (e.g., from Poland). (Martena et al., 2022, p. 16).

In 2000, there were 1074 general schools in Latvia. Out of 334,572 students, 203,012 students (61%) learned in Latvian, 93,799 students (28%) learned in Russian, and 36,427 students (11%) in Latvian and Russian (Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia, 2000).

In 2022, there were 678 general schools in Latvia, of which 527 were considered to be so-called Latvian schools (77%) providing instruction only in Latvian (140,161 students), 115 schools were mixed schools providing instruction in Latvian and Russian (57,823 students), 25 schools were seen as so-called Russian schools providing instruction in Russian (3917 students), and 11 provided instructions in other language, for instance, Polish, Ukrainian, German, and Belarusian (3206 students) (Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia, 2022).

Starting with the school year 2023/24, there is no longer general education institutions where the MOI is only Russian. However, out of 618 schools, there were 115 mixed schools with provided instruction in Latvian and Russian (55,820 students) (Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia, 2023).

3.4. Recent Changes in Latvian Language Policy

In modern Latvia, the goal of the language policy is to ensure the sustainability of Latvian, the state language of Latvia and the official language of the EU, its linguistic quality and competitiveness in the Latvian and world language market, as well as its influence in the cultural environment of Latvia. To achieve the goal of the state language policy, four directions of actions have been determined: (1) strengthening the legal status of the state language, (2) state language education policy, (3) scientific research and development of the state language, (4) ensuring public participation in the implementation of the state language policy, and (5) the development of the Latvian language (Druviete, 2021, p. 14).

The following subsections briefly touch on three above-mentioned directions: the first two (the legal status of the state language and the state language education policy) and the last strand (the assurance of public participation).

3.4.1. The Legal Status of the State Language

In 1999, the Official Language Law (Saeima, 1999) was adopted, stipulating that the only state (“official”) language is the Latvian language. The law recognizes the Liv language as the language of the indigenous (autochthon) population. The Latgalian written language, spoken in the Eastern part of Latvia, is defined as a historic variant of the Latvian language. All other languages are foreign languages within the meaning of the law.

In connection with the language law and other regulations governing the use of language, several important events have taken place in the last decade. Since 2017, the Official Language Law has been amended several times to determine the extent (level and degree) of knowledge of the state language for professions whose representatives’ activities affect legitimate public interests. In 2018, the Electronic Mass Media Law was amended to ensure the use of the state language in cross-border programs (e.g., at least in subtitles on TV broadcasts and documentaries). However, the most significant amendments at the level of legal acts adopted by the Saeima (Parliament) were made in the laws affecting the education system.

3.4.2. The Minority Education Reform

In Latvia, in 1989, the Education Law was adopted. Since then, a gradual transition to the Latvian language as the MOI has been implemented in all educational institutions and at all stages of education, also providing the opportunity to learn the language and culture of minorities. Thus, since 1989, learning Latvian as a school subject has been mandatory in all educational institutions. Since 1992, there is an attestation of the state language proficiency for pedagogues. Since 1995, two subjects have been taught in Latvian in primary school, three in secondary school.

In 1999, four free-of-choice bilingual education models were introduced. Then, in 2004, a ratio of 60–40% of MOIs (Latvian and minority languages, respectively) was introduced in secondary schools. Since 2008, all students take the same Latvian language exams. Then, since 2021, all general education subjects in secondary schools are taught in Latvian, minority languages are kept teaching subjects related to culture and history. A full transition of all class groups to learning exclusively in Latvian except for the subjects of mother tongue and cultural history is planned to be implemented by 1 September 2025 (see more in Druviete, 2021, pp. 22–25; Hogan-Brun, 2003, 2007; Lazdiņa & Marten, 2019).

As Hogan-Brun (2003) puts, the education reform is based on the idea of national cohesion and all inhabitants’ full participation in the life of the nation through the national language (Hogan-Brun, 2003, p. 125). According to her (2007, p. 556), the educational transition in Latvia was more complex than in the two neighboring countries—Lithuania and Estonia—mostly because of its ethnolinguistic situation. In Latvia, the Latvian-ethnic population decreased by about 20% in the late 1980s due to the Soviets’ successful shifting the ethnic balance and of the russification policy, and more than a third of the population (both people of Russian nationality and many members of other ethnic communities) claimed Russian as their first language. After independence, asymmetric bilingualism emerged in Latvia and a newly introduced language policy supported official monolingualism, with Latvian as the sole state language.

3.4.3. Public Participation in the Implementation of the State Language Policy

Active involvement of society in language policy and management can be seen in various ways, including social actions, campaigns, and protests. Here two examples that shook language management in Latvia will be presented; both took place in 2011. The first was a signature collection campaign initiated by the nationalist-conservative party, or the National Alliance “All for Latvia!”–“For Fatherland and Freedom/LNNK” (Nacionālā apvienība “Visu Latvijai!”–“Tēvzemei un Brīvībai/LNNK” in Latvian), for changes to the Constitution, stipulating that the state provides the opportunity to obtain free primary and secondary education only in the Latvian language. The required 10,000 signatures were obtained to propose to the Parliament such changes. This event was soon followed by the second event: the political party “United for Latvia” (Vienoti Latvijai in Latvian) and the society “Native Language” (Dzimtā valoda in Latvian) begun collecting signatures for the Russian language to be recognized as the second state language in Latvia. More than 12,000 signatures of supporters of the idea were obtained. An application with these signatures initiated a referendum on changes to the Constitution, providing the Russian language with the status of the second state language in Latvia. The referendum was held in 2012, and 70.37% of all eligible voters participated in it. The result of the referendum was as follows: 74.8% of the voters voted Against the Russian language as the second state language, and 24.88% voted For. Thus, the proposed changes in language policy were rejected (see more in Druviete & Ozolins, 2016; Liepa, 2016b, pp. 226–230).

Both social actions indicate the conflict between the titular group (Latvians) and the largest minority group (Russians) regarding the status, prestige, and use of Latvian and Russian in Latvia. Both initiatives ended up without desired outcomes for the initiators in the particular settings.

4. Materials and Methodology

4.1. Data Collection

Research sources are online news articles (hereinafter ONAs) about protests on minority education reform between 2004 and 2024. The period was selected taking into account the time coverage of previously conducted research (see Section 1), the year 2004 as a significant turning point in the implementation of minority education reform (see Section 3.4.2), and ONAs with visual illustrations of the LL in protests (photos/videos) found on the web.

ONAs were searched on Google using keywords in Latvian, Russian, and English related to the goal of the article, for instance: demonstration/protest/picket/rally against minority education reform; transition to teaching in Latvian; students protesting against the Latvian language in education; Hands off Russian schools (i.e., the main slogan by protest organizers, see below). The main criterion for the selection of ONAs was the inclusion of photo or video with at least one readable written text, LL sign, from the protest(s) discussed in the relevant article. Google was used to avoid on focusing exclusively on certain news portals and to include potentially different perspectives on the representation of the LL of protests in Latvia. In result, 29 websites were viewed (see Appendix A), and an article corpus was created with 77 ONAs: 26 in Latvian, 31 in Russian, and 20 in English. The selected ONAs mainly come from leading Latvian news portals (according to LASAP, 2024; Gemius, 2017), publishing articles in Latvian, Russian, and English (e.g., TvNet; Delfi; Apollo; Latvijas Sabiedriskie Mediji, or LSM; Diena), followed by Russian propaganda websites in Russian and English (e.g., TASS; Gazeta; Baltnews), and European news portals in English (e.g., BBC; The Baltic Times; Euractiv).

Next, fragments of ONAs mentioning written texts displayed in protest(s) (in other words, the LL of protest(s)) and photographs with LL texts of protests were subjected to data analysis. Additionally, I reviewed comments attached to the selected ONAs, but they are of secondary importance to this article since the focus of the article is on the representation of the LL of protests by news portals.

4.2. Data Analysis

The research mainly follows qualitative approach principles. ONA analysis began with a general description according to the following criteria: (1) year of publication, (2) language of the article, (3) number of photographs and/or videos, and (3) explicit mentions on the LL texts of protest(s) (included or not, respectively. In this sense, the total number of mentions could not be higher than the number of selected ONAs).

Further, additional attention was paid specifically to fragments of ONAs with included mentions on LL texts of protests. The length of description of LL texts was not considered when counting the mentions; it could be a short sentence about protesters holding banners or a long and detailed comment listing several slogans as quotes. Then five pre-formulated research questions were considered:

- What do the photographs of LL texts from the protest(s) included in the selected articles show readers?

- Who is the author of the ONA fragment (mention) regarding the LL texts of the protest(s)? For instance, have protesters, invited experts, politicians, or residents commented the LL texts?

- What is the aim of mentioning the LL text(s)? Does the mention repeat what is already said in photos/videos; shown a translation of LL text(s) in the language of the article (if the language use is different); express opinion about language(s) used in protests; support one’s own or someone else’s claims or arguments, etc.?

- How detailed is the mentioning of LL text(s) of protest(s)? Does it reference the LL text(s), quote and/or describe LL texts in relation to authors and/or demonstrators, compare with LL text(s) in previous protests or LL text(s) of similar protests in other countries, etc.?

- What discourses about minority education reform, protest participants, the LL of protest(s), and protest culture in Latvia do the mentions create or reiterate?

To examine the photos/videos with LL texts included in the ONAs, a qualitative content analysis method was applied (Mayring, 2004). The method consists of a three-stage analysis: a sociolinguistic and textual analysis of the LL signs, a summarizing content analysis, and a thematic grouping of these summarized messages at a higher level of abstraction. LL texts analysis has been influenced by one of the discourse analysis approaches–Frame Analysis. It is based on the idea that discourses can be seen as frames, that is “structured understandings of the way aspects of the world function”, as Fauconnier and Sweetser (1996, p. 5) argue, and can be thought of “as culturally or sub-culturally structured and structuring sense-making resources” in the words of Coupland and Garrett (2010, p. 15). Frame Analysis is a constructive approach to examine and conceptualize texts (in our case, LL signs) into “empirically operationalizable dimensions—syntactical, script, thematic, and rhetorical structures—” in a way that the “framing of issues” in the data may be uncovered (Pan & Kosicki, 1993, p. 55). In other words, the set of LL signs of protests is a point of departure to categorize meanings, or simply, frames of meaning (Ben-Said & Kasanga, 2016, p. 74). McLeod and Hertog (1999) identify four key frames, or overarching narratives, in media coverage of protests: riot, confrontation, spectacle, and debate. The riot (violent, deviant disruptive behavior), confrontation (conflict with authorities, police, and opposition), and spectacle frames (sensational, dramatic and individualistic narratives) emphasize action or behavior. They tend to delegitimize the movement and negatively affect public opinion. In turn, the debate frame discusses the agendas or demands of the protest, and the inclusion of this frame in media coverage is an opportunity to engage audiences with the substance of the issues advocated by the movement (see also in Brown & Harlow, 2019).

Critical discourse analysis was used to the extent of revealing the interdiscursive and intertextual character of media discourses, exploring how certain ways of representing the world, performing identity, and constructing social belonging are normalized in media spaces; questions of who gets to speak, what discourses are privileged, and what discourses are absent or foregrounded (Phelan, 2017).

5. Results

Table 1 provides a description of the selected ONAs (see the first paragraph of Section 4), showing (1) how many ONAs and in which languages were found in various years, (2) how many photos/videos were included in the selected ONAs, and (3) was LL texts mentioned in the selected ONAs, or not.

Table 1.

Description of the selected online news articles, or ONAs.

Table 1 shows three important things. First, protests gained wide media attention in 2018, when the Latvian government adopted amendments to the Education Law of the Republic of Latvia and in the Law of General Education for a complete transition to Latvian as the sole language of instruction from 1st to 12th grade and when a wave of protests occurred in Riga. ONAs about the protests were actively published in both national and international news. Therefore, the first three excerpts below are the most extensive, showing the broader context before and after the mention of the LL of the protest. They illustrate fragments of the coverage of the June 2 protest and inclusion of descriptions of the LL of the protest in news articles by Latvian, European, and Russian news media. According to the law “On Meetings, Processions, and Pickets” (see Section 3.1), it was the procession in which oral announcements alongside written placards were allowed.

The text prepared by the largest Latvian news agency LETA is used in the article “Protest in Old Riga Against Transition to Latvian-language Education, Few Young People Participate” on the website LA.lv. Excerpt 1 shows that the LETA journalist(s) conveyed the following messages to the reader through the article: (1) this protest was not the only protest against the education reform organized by the socially conservative political party “Latvian Russian Union” (Latviešu Krievu savienība in Latvian), (2) the number of students at the protest was small, (3) the protesters held national and pro-Russian party’s symbols and placards in various languages, which expressed the protesters’ desire to protect the children of the Russian minority, the solidarity of the Russian community in the fight against linguistic and political injustice, and the dependence of national loyalty on the respect for the rights of ethnic/linguistic minorities (some of these placards were prepared by the organizers), (4) the protest organizers orally promised the attendees to show the government their political power and influence so that Russian interests would be respected in the country.

Excerpt 1 (LA.lv, 2018; originally in Latvian1)Today, approximately 500 people gathered at Riflemen’s Square in Riga for another protest action organized by the “Latvian Russian Union” (LRU) against the gradual transition to education in the Latvian language, but after the later march to the Cabinet of Ministers building, the number of participants increased to approximately 1000. However, there were few school-age youth among the protesters.As observed by the LETA agency, before the rally, LRU leaders Tatjana Ždanoka and Miroslavs Mitrofanovs organized the distribution of small-sized, most likely children’s drawings to the attendees, on which was written in various languages, mostly Russian, “Our children—our rights”. Those present held both Russian and Latvian flags, as well as flags with LKS symbols and placards that read in various languages “The school year is over, the fight continues”, “Russians do not give up”, “Stop the language genocide!”, “If there is no respect, there is no loyalty”, “Learn Latvian-yes! Learn in Latvian-no!”, “This is not reform, this is repression!”, “Russian is the language of victory”, “Rights in the morning, loyalty in the evening”, “No to assimilation!”, etc.Speakers from the stage occasionally encouraged the crowd to chant various slogans together. For example, deputy Jakovs Pliners “moved” the audience with such exclamations as “Reform—a nightmare! Reform—no!” and “United we are invincible!”, while Ždanoka shouted “Let’s protect the children!”. Mitrofanovs promised the crowd that, despite the attempts at intimidation, the fight for Russian as the language of instruction in schools will continue and be won. “This country will be ours, and the power of this country will work according to our dictates!” the LRU co-chairman told the protest participants.

European news portal Euronews published the article “Children go native as Latvian schools say ‘Nē’ to Russian”. Excerpt 2 shows that it contains the emotionally charged description of the procession with mention of one placard shown in the protest, the feelings of the Russian minority (especially parents), who are aware that their native language is defined as a foreign language in Latvia (see Section 3.4.1), and emphasis on both the political fight and the language conflict in Latvian society exacerbated by the reform. Like the Latvian news agency, readers are reminded that protests against the reform are common in Riga.

Excerpt 2 (Euronews, 2018; in English)Demonstrations over school reforms are nothing new to the picturesque Baltic metropolis of Riga. The Latvian capital witnessed the latest protest on this hot topic at the beginning of June. A march from the Latvian Riflemen Monument in the center of the city’s old town to the seat of government numbered over four thousand as drums punctuated the battle cry of “hands off Russian schools!”Aleksandrs Bartaševičs, the mayor of Rēzekne—a town with a very high percentage of Russian speakers—called this reform “a crusade against Russian schools”. Many parents agree. “I believe, when a language that is native for over a third of the country’s population is treated as foreign, it’s nonsense”, says mother-of-three Eugenia Kriukova. “We are not foreigners, and we are not going to become them.” (…)School reform can be seen as a political fight for both the authors of it and the movements resistant to it and let’s not forget that elections are on the horizon in the autumn. Transferring education in all schools into Latvian was one of the key points in the manifesto of National Alliance “All for Latvia!”—“For Fatherland and Freedom”—a nationalist party that is now part of the ruling coalition in parliament. A fight against this reform will breathe new life into the “Latvian Russian Union”, a party that has been silent for many years and has lost most of its voters to “Harmony”, a center-left party supported by many Russian-speakers.

In contrast, Ekaterina Sislova (Eкaтepинa Cycлoвa in original), the author of the article “We Will not Give up”: How to Save Russian Schools in Latvia” on the Russian news portal Gazeta, in contrast to the previously cited news fragments in Latvian and English, points to Russia’s possible reaction to the next step in the minority education reform, its involvement in the political and social life of Latvia. The article also includes information about the poster hidden on other news sites, which did not meet the legal requirements for organizing a protest (see Section 3.1). More than articles on Latvian and European news portals, this ONA highlights concerns about minority children and the protection of their linguistic rights.

Excerpt 3 (Gazeta, 2018; in Russian)A rally in defense of Russian schools was held in Riga, with almost four and a half thousand people taking part in the march. Similar protests began back in March in response to the start of an educational reform that would involve switching all schools in Latvia to the Latvian language by 2022. The actions of Latvia, where a large number of Russian speakers live, have provoked the indignation of Moscow—the State Duma even proposed introducing economic sanctions in response.On 2 June, the “March in Defense of Children” was held in Riga—a rally against the discriminatory policy of the Latvian authorities towards Russian-language schools. According to the organizers, almost four and a half thousand people joined today’s march. The rally started at 12:00 local time (13:00 Moscow time) from the Latvian Riflemen’s Square in the historical center of Riga. From there, the protesters headed to the Cabinet of Ministers building located on Freedom Boulevard, chanting the slogan: “Hands off Russian schools!” The protesters carried banners with slogans in Russian and Latvian: “Russians do not surrender!”, “Our children are our right!”. Even before the march began, a small incident occurred among the protesters—several activists brought a provocative poster about the occupation, which was taken away and trampled by other protesters. The police had to intervene—they took away the instigators of the scandal.The rally in defense of Russian schools in Latvia was led by Miroslavs Mitrofanovs, Member of the European Parliament, and the leader of the party “Latvian Russian Union” Tatjana Ždanoka.

As can be seen, all three news portals explicitly show the organizers of the protest and the march route, briefly describe the participants (although their number varies across news sites), and mention the LL of the protest. All ONAs address the discriminatory nature of the education policy from the point of view of representors of the Russian minority in the protest, the sentiment of the Russian minority in relation to language policy, and the role and importance of the Russian language in the country. The ONAs also indirectly raise national security issues (i.e., through the quoted public promise of Mitrofanovs and the removal of the provocative poster).

Second, Table 1 shows that photos with LL texts from protests are significantly more included in articles in Latvian; 489 photos in total are part of the 26 ONAs. The average number is 19 per article, compared to articles in Russian with the average of 4 photos and to articles in English with the average of 1 photo.

Third, the number of mentions of LL texts is more frequently included in articles in English (16 cases out of 20 articles), compared to articles in Latvian and Russian (19 out of 26 and 13 out of 31, respectively).

The following subsections answer the research questions defined above regarding (1) typical features of LL texts of the protests, (2) commentators on LL texts, (3) purposes of the mentioning LL texts, (4) the level of detail of the mentions, and (5) discourses about minority education reform, the protests, protest participants, LL of protests, and language of LL texts of the protests.

5.1. Common Features of LL Texts of the Protests

One of the typical features of the selected ONAs is the use of photo(s) with LL texts of the relevant protest as their cover images. Almost all the ONAs have a titular image showing LL text(s). The examination of them shows two things. First, the photographs either draw closer to a single placard with an eye-catching message or depict a broad mass scene with numerous, partially readable or unreadable LL texts (see Figure 1 as an example). The highlighted placards most often speak on behalf of minority communities (mainly Russian), thus expressing the opinion or position of all minority groups or one entire group, most likely the Russian community. Examples include “[We] won’t forget and forgive, Russian schools—our choice, and Russians won’t give up” (all originally in Russian). Significantly less often, the placards illustrate an individual position that, due to the generalization of the content, can be applied to a wider group—minority students or entire community, for instance, “I am Latvia” in Latvian and “I want to learn in native language” in Russian.

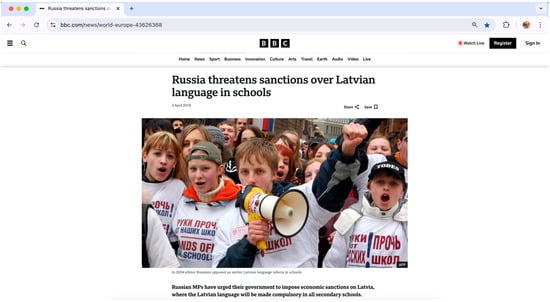

Figure 1.

The titular image of BBC’s article about a protest in 2018. (Screenshot from BBC.com on 2 February 2025).

Interestingly that two ONAs have re-used a photograph of an earlier protest: BBC article in English in 2018 and Baltnews article in Russian in 2021. Figure 1 shows the first case—the article has a photograph from a protest in 2004, and this fact is indicated under the image. However, the photograph can give misleading impression of the wide participation of students in the later protests too. Likewise, the central boy’s loudspeaker and hand gesture illustrate the students’ active agency: constant leadership and voice demanding to be heard.

Cover images, illustration of LL text(s) are frequently in Russian, thus indirectly placing a marker on the ethnic/linguistic profile of the participants involved in the protest(s).

The sociolinguistic analysis of the LL texts depicted in the photo/video galleries of ONAs shows that three languages—Latvian, Russian, English—are used in all examined protests. Combining the quantitative with the qualitative approach, we can see that each language has a slightly nuanced function in protests. Texts in Russian contain heavy criticism of the changes, the most categorical and emotionally charged statements, and more aggressive demands. A belonging with Latvia and support for knowledge of Latvian are more emphasized in texts in Latvian. English has been used to highlight the risk of discrimination, the values of a democratic society, and the public need for a unifying and loyal linguistic diversity (see examples throughout the article).

The use of identical slogans both in Latvian and Russian on one or two separate placards is the next typical feature of the LL texts of the protests. These are likely trying to reach readers from both major ethnic/linguistic communities. Figure 2 serves as one example. The article “Protest Action in Riga Against School Reform” in Russian on the website Euronews in 2017 is presented by the photograph with five LL texts. In the center of the image is an order “Enough!” in Latvian and Russian. Although the text is identical in both languages, the use of red color, italic font, and black shading highlight the text in Russian. The drawing of the former Minister of Education and Science, Kārlis Šadurskis, shows to whom the text is mainly addressed. This placard can be seen as an ideological clash if we assume that the text in Latvian shows Šadurskis’s political stance and move (i.e., Enough is enough to offer the Russian language as the MOI in schools in Latvia) and the text in Russian demonstrates the protesters’ response (i.e., Enough, Šadurskis, of changes in Latvian education). To the right of the bilingual placard are three monolingual texts in Russian—“Hand off Russian Schools” (2x) and “Reform–Nightmare, No to Reform”—and one partially legible text in English (i.e., a part of the slogan “No discrimination!”).

Figure 2.

The LL texts of the protest in 2017. Central placard includes bilingual order “Enough!” in Latvian and Russian (Screenshot from ru.euronews.com on 4 March 2024).

5.2. Who Describes the LL Texts of the Protest(s)?

In all articles, journalists are those discussing on LL texts of the protests, and no expert or activist is invited to publicly express thoughts on language and/or content of LL texts in the protests and their (possible) impact on the development of minority education reform and/or public opinion.

A journalist name is indicated in 22 ONAs (out of 77), and, in five of these cases, the ONAs are co-publications by two authors (three articles in English, one article in Latvian, and one article in Russian). Three ONAs has a statement that a (non-specified) correspondent of relevant news portal or news agency prepared the article. In other ONAs, the authorship is attributable to the news portal or news agency from which the information for the article is taken. In turn, authors of photographs and videos are always indicated in ONAs.

In the comment section, ONAs’ readers pay little attention to the LL texts of photos/videos. A few exceptions include comments on spelling mistakes in Russian and English texts and on the main slogan of the protesters (“Hands off Russian schools”). Two examples illustrate this. The first is the statement “Politikal Terror in Eirop/This is our Realiti” from the protest in 2004 that received the following comment: “I don’t know why those stupid people thought to write that slogan in ENGLISH (the one on the photo), and it’s also wrong!!!!:-) Well, isn’t it ironic!:-))))” (TvNet, 2004b; in Latvian). The second is anonymous commentor’s opinion: “If ‘hands’ means state funding, then definitely–“Hands off Russian schools!”” (Delfi, 2019; in Latvian). Here the public funding is seen as the main criterion for minority school (at least Russian) autonomy.

5.3. What Are Possible Aims of the Mentions?

Giving readers an idea of the atmosphere of the protests and sharing the most important messages from the protests, thus showing what protesters stand against/for and their main counterarguments to changes in minority education, can be considered the main goals of the mentions of the LL of the protests. To do this, authors of ONAs have chosen to provide all protest slogans in the language of the article.

An equally important goals of the mentions are the desire of the authors to (1) name protest organizers (mainly pro-Russian politicians Tatjana Ždanoka and Miroslavs Mitrofanovs, Latvian Russian Society, and the Latvian Association for the Support for Russian Language Schools), (2) highlight that people of the middle and older generations are the ones typically holding placards, (3) draw readers’ attention to the fact that protest organizers distribute placards to be shown and lyrics for sing-alongs before or during the protest, (4) name the politicians (mainly ministers of Education and Science and prime ministers) who have been criticized by the protesters; (5) provide a brief overview of the development of the reform through the messages shown in the LL texts.

5.4. How Detail Are the Mentions About LL Text(s)?

Content analysis of ONAs shows that there are at least four approaches how LL of the protest(s) are mentioned: (1) referring to placards with written information alongside aurally shared information and semiotic attributes of the protest(s), (2) emphasizing the number of placards’ holders, their belonging to a specific group (political, ethnic, linguistic) and age, (3) citing a few slogans as examples, and (4) comparing several protests and highlighting the fact that some slogans repeat from one protest to another.

LL texts are described briefly, mainly in 1–2 sentences and together with protestors’ speeches, shouted phrases, and songs sung together. If there are any semiotic signs or elements visible in the protests, which author(s) of the relevant ONA found essential, they are also mentioned alongside the written information. Flags (Russian, Latvian, and protestors’ organizations), the ribbon of Saint George (Russian military symbol), and the use of red color in the design of protest items (placards, balloons, ribbons) are the most typical examples (see, for instance, Excerpts 1–3).

Excerpt 4 shows not only the first three above-mentioned approaches in describing the LL of protest but also emotional assessment of the protest by anonymous author(s). The choice of lexical means (e.g., ‘deafening volume’ instead of ‘volume’, ‘special placards’ instead of just ‘placards’, and ‘loudly shouted’ instead of simply ‘shouted’, and the use of word pat ‘even’ in the last sentence) try to dramatize the event, highlighting the hooligan behavior and revolutionary tone of the activists.

Excerpt 4 (TvNet, 2004a; in Latvian)This morning, almost 1000 students from several Russian schools gathered at a picket in front of the Ministry of Education and Science, chanting slogans at a deafening volume: “No to reform!” and “Hands off Russian schools!”. The teenagers have prepared special placards, and many are wearing uniform shirts that say: “For Russian schools”. The young people occasionally shouted “No to reform” loudly, made obscene gestures at the ministry employees, who occasionally came to the ministry’s windows. Some activists even tried to throw snowballs at the ministry.

Despite the large representation of students in the 2004 protests (~10,000), later years the core of the protesters were members of pro-Russian political parties and societies and Russian-speaking seniors. The age of the demonstrators is mentioned in almost every ONA (see, for instance, Excerpt 1 and 4) and ironically mocked by many of the articles’ commentators. The demonstrators who hold posters with the text from the position of students are especially harshly mocked, calling the holders of such texts “eternal students” and expressing regret that Russians must study in Latvian schools for so long. Similarly, if children with placards participate in the protests, this fact is always highlighted. For instance, the statement “I want to learn 100% in Russian” in Russian, held by small children in several protests since 2018, has widely covered on media.

Protest slogans are included both in ONAs’ headlines and their main body. Four headlines of the ONAs have slogans from the describable protest. They are: “No to assimilation” in Latvian and “We won’t give up”; “Hands of Russian schools!” and “We are not slaves. Slaves are mute” in Russian. The slogans mark the perseverance of activists and the perception of education reform as the authority’s power to silence the voice of minorities. On the other hand, on average, three slogans as quotes from the protests are included in the main body of ONAs, thus representing the LL of the protest(s) a whole. 11 slogans are the highest number of quotes in one ONA in Latvian. Five ONAs retell the essence of the content of the LL texts instead of direct quoting them. Excerpts 5–7 illustrate this approach in describing the LL texts of the protest.

Excerpt 5 (The Baltic Times, 2004; in English)Pupils held signs in Russian, English and Latvian excoriating educational reform, the human rights situation and Latvia itself. At another protest the following day in Esplanade Park one sign warned that the education reform could lead to a Baltic Kosovo disaster.Excerpt 6 (Delfi, 2017; in Russian)Protesters with placards and flashlights in their hands demanded to preserve education in Russian.Excerpt 7 (NRA, 2018; in Latvian)The main message of the posters was directed against the complete transition to teaching in the state language in secondary school, calling such a plan “violent assimilation”.

Excerpt 5 shows that readers must know about (1) education reform, (2) activists’ interpretation of human rights and their observance in Latvia, and (3) the case of Kosovo. The article does not directly state the opinions of the protesters about educational changes and their impact on the population of Latvia (or a large part of them). On the other hand, Examples 6 and 7 show the intentions of the protestors. The latter additionally provides activists’ apprehension of the minority education reform.

A comparison with previous protests is another approach in portraying information about the LL texts of the protest(s). The latest protest (the focus of the relevant ONA) has most often been compared to one or two previous protests. It is done to highlight the similarities between them in terms of the number and age of participants and the main messages of the protests, which are related to the protestors’ goal of preventing changes in minority education. Only one ONA in Russian additionally includes two photos from recent protests for comparison.

It is typical to repeat slogans quoted in previous ONAs, other news portals, or ONAs in another language. The most frequently repeated LL text is one of the main slogans of the protest campaign, “Hands off Russian schools!”, which is included in 13 ONAs in all article languages and in one the article title (see above), therefore it has been picked for the title of this research article as well. Several ONAs describe the slogan as “already common,” “widely chanted”, and “more than ten years old”. Since 2018, the slogan “Russian schools should be” in Russian has become prominent. Originally, it is quote by Catherine the Great at the end of the 18th century after the first Russian school opening on the territory of Latvia, and this reference is mentioned in four ONAs in Russian and English prepared by the Russian news agency TASS.

Finally, it should be added that no ONA provides the link between the ONA and titular image of it and gives an indication of the photo/video gallery (if any) attached to the article. In other words, there is no guidance to look at the photo/visual materials for evidence of statements or additional information. Thus, the ONA and photo/visual information as attachments to the article can be considered two or three autonomous sources of information.

5.5. What Are the Main Discourses?

According to McLeod and Hertog’s (1999) identified key frames in protests’ coverage in news (i.e., riot, confrontation, spectacle, and debate), the presentation of Latvian protests against minority education reform on online news portals refers to a debate frame with certain spectacle frame features.

Content analysis of the coverage of the LL of protests in 77 ONAs shows that the ONAs mainly emphasize the position of the activists, showing those things that the protesters are targeting through the LL texts and which they publicly criticize (i.e., minority education reform, discrimination, assimilation, the destruction of Russian schools and of the Russian language). Only four ONAs show that activists advocate for the education of Russian minority children in their native language and the preservation of Russian schools. Three of these articles are prepared by Russian news agencies. And only one Latvian national news portal had the description of the LL texts in which first the slogans that illustrate the wishes of the protesters, following by the slogans that criticizes the minority education reform (LSM, 2019). In this vein, the LL texts of the protests function as a public way to object and criticize the opposition—the government—and its planned, adapted, or implemented changes in education.

5.5.1. The Main Narratives

The nature of the protests and their participants ground the dissemination and reinforcement of key themes, narratives, and discourses. However, the coverage of the LL of the protest(s) on the online media depicts a significantly narrower range of issues than the article’s photo/video materials. The main narratives, or frames, that are reinforced through the descriptions of the LLs included in the articles are two: (1) the Russian community is united and persistent in the fight against the ethnolinguistically unjust education policy pursued by the government, and (2) students, parents, and the Russian community as a whole should have the right to choose which educational program to study at their schools.

The articles in Russian (especially by the Russian news media) repeatedly emphasize that the Russian community is united and persistent in its fight against linguistic/ethnic discrimination in Latvia. The LL texts of protests indicate that nationalization carried out by Latvians (mainly Latvian political forces) is fascism and ethnolinguistic totalitarianism at the expense of linguistic assimilation (also called linguistic genocide by protesters). The government’s decisions related to minority education have been seen as a way of showing power to target the minority, mainly Russian community, and push the Russian language out of the practice of language use in Latvia.

The 2018 protests, which also included support groups from other Latvian cities where Russian-speakers constitute a large part of the population (e.g., Daugavpils and Rēzekne from Eastern Latvia), have been widely covered in the ONAs, considering the territorially wide area of support (see Excerpt 2). Such LL texts as “I am Latvia”, “We [are] Latvia” in Latvian or Russian and “We, Latvians (!) are against full transition to education in Latvian” in Latvian show that the protesters try to emphasize the fact that they are also Latvians, a part of Latvia, which is linguistically and ethnically different from the title nation and which cannot be ignored in the planning and implementation of language policy. The preservation of minority (mainly Russian) schools with minority languages as languages of instruction has been seen as one of the strategies to prevent ethnic and possibly military conflicts. The LL text “Russian Schools—Peace in Latvia” in Russian proves this.

However, photo/video materials provide more nuanced information, implicitly touching the topic of Latvian inhabitants’ loyalty and patriotism. For instance, a photo with the visually simple poster on an A4 sheet of paper shown at a protest in 2018—“You Will not be Loved by Force and You Will not Build a Happy Country [by Force]!” in Latvian—shares the idea that social changes imposed by the authorities in minority communities will not cause positive emotions towards the oppressors and will not contribute to the well-being of all citizens of the country. The opportunity to get an education in the native languages of all Latvian residents is associated with mutual respect, which is the basis of the guarantor of loyalty to the country. The slogan “If there is no respect, there is no loyalty” in Latvian shown in another protest illustrates this.

The second message cultivated in ONAs highlights the need for autonomy of minority schools in language management and the right of parents (communities) to choose the language of instruction for their children (the next generation). The slogans cited in the articles from the LLs of the protests—“[We are] For free choice of language of education!” in Latvian and Russian, “Russian Speech in schools” in Russian, “Our children—our choice” in Russian, “Our children must have our schools” in Russian, “We shall defend our Russian schools” in English, and “[We] will not betray our children” in Russian—show this.

However, the articles barely mention the issue of education quality, which also slightly appears in the LL texts of the protests included in the photo galleries. Examples include “[We stand] For meaningful education, against meaningless reforms” in Russian, “Be punished for quality education in the native language, the Russian language” in Latvian, and “Better education in the native language” in Latvian. Bilingual LL texts in Latvian and Russian, shown at a protest in 2019, demonstrated prominent Latvian historical figures who studied in Russian schools (e.g., film director Sergej Eisenstein, professor and politician Ivan Jupatov, comedian and playwright Mihail Zadornov) and received international recognition. These public texts tried to function as examples of the effectiveness of minority programs and student excellence.

5.5.2. Acknowledging Multilingual LL of Protests

In the context of traditional LL studies, an important discourse in the media is the recognition of the multilingualism of the LLs of the protests. The description of the LL of the protest(s) in ONAs hardly includes any information about the use of languages; where such information is included, it is included rather carelessly. 11 ONAs out of 77 examinees mention language(s) used in LL texts. Although the photos/videos included in ONAs show the use of three languages—Latvian, Russian, and English—in all protests, they all are listed only in three ONAs. Two languages—Latvian and Russian—are named in four cases. Other ONAs mention one language, state that one language is mainly used, or utilizes words of uncertainty such as ‘several’, ‘various’, and ‘different’, without specifying any language (see, for instance, Excerpt 1).

Similarly, the real language situation is not shown by the quoted slogans, since they all are translated into the language of the article without any indication of their original language. Excerpts 8 and 9 are the only exceptions that at least partly names visible languages of the quoted LL texts.

Excerpt 8 (Delfi, 2019; in Latvian)The gathered protestors wore shirts with pins that read “Russian schools forever!” in English on their overcoats and coats. Several placards were also prepared in English, for example, which in translation would read “Stop linguistic genocide!” and “Our language is our soul, our right!” The protest also featured posters in Latvian, such as “Learn Latvian—Yes! Learn in Latvian—No!” [emphasis by the author]

However, although the titular image of this ONA presents six placards in Russian, it is excluded of the description of the LL of the protest.

Excerpt 9 (TvNet, 2024; in Latvian)One of the protesters is holding a large Latvian flag, while the man standing next to him is holding a placard with the inscription in Russian “We are Latvia.” Another protester is holding a placard with the inscription “For free choice of language of instruction”, and another is holding a placard with the inscription “To learn in the native language”. [emphasis by the author]

Example 9 provides unclear information about the language used in the LL texts. Although all slogans originally are in Russian, the reader may get the impression that only the first slogan quoted is in Russian.

5.5.3. Perception of the State Language and the Russian Language

An equally important sociolinguistics-related discourse is protestors’ perception of the role and value of the state language and minority language(s) in Latvian society. The mentions of the LLs of the protests show how activists perceive the Russian language and the state language. The Russian language is characterized as “my/our language”, “our soul”, “mother tongue”, “our right”, and “more than a language”. The Latvian language, in turn, is described as “second language”, which must be studied in schools as one of the subjects. In one case the symbolic meaning of the language is highlighted (implicitly also the cultural aspect), while in the other case the political criterion is essential in the description of the language. Language use, economic value, and the socio-pragmatic importance of languages in Latvia are not mentioned.

Surprisingly, provocative LL texts such as “Russian is the Language of Victory” and “A Strong Coffin for Every Russophobe”, both originally in Russian, each included in two ONAs, but not discussed in any. The first can be perceived as an indirect reference to the sociolinguistic experience in Soviet Latvia (as a part of communism ideology, language policy and practices), while the second balances between freedom of speech, depicting the tension in ethnic relations in Latvia and the incitement of ethnic hatred; both are under question of legibility (see Section 3.1). Similarly, journalists have not paid attention to the posters in 2017 which show large images of an old homeless male person and a dead female body due to drug overdose and the text “Thank you. Now I speak Latvian” in Latvian, visually representing the possible consequences of the implementation of the education reform in an emotionally heightened way. Both multimodal placards represent spectacle frame, or dramatic and individualistic narrative (according to McLeod & Hertog, 1999).

It should be added that the media coverage of the protests does not inform readers about the approximate number of placards in the protests (e.g., Are there three or thirty placards?) and the typical features of the placards. Moreover, media do not speak about differences in placard content based on the language used in LL text(s). In other words, the linguistic and sociolinguistic description and texts analysis of the LL texts is missing.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

The goal of the paper was to identify and characterize ways in which 77 online news articles published on Latvian, Russian, and European news portals between 2004 and 2024 portrayed the LL of protests against minority education reform and to note the main discourses related to that LL.

In result of content analysis of ONAs, four typical approaches in portraying LL of the protest(s) were defined: (1) referring to placards with written information alongside aurally shared information and semiotic attributes of the protest(s), (2) emphasizing the number of placards’ holders, their belonging to a specific group (political, ethnic, linguistic) and age, (3) citing a few slogans as examples, and (4) comparing several protests and highlighting the fact that some slogans repeat from one protest to another. News authors often use the strategy of quoting slogans already demonstrated in previous protests, which readers, most likely, already recognize and can form specific associations with the protest participants—representatives of the Russian community—and their main message—the Latvian government’s decisions on language in education are unfair and discriminatory.

The examined ONAs allow photos with LL texts to speak for themselves, as there are no direct references to photo/video galleries in the articles and their description in the written part of the articles is very laconic, general, even in many cases superficial and careless; for instance, ignoring the emotional language, hate speech, potentially ethnic hatred-inciting texts, and dramatic visual images revealed by protest posters. The authors of the articles also pay almost no attention to the languages used in the protests, offering the quoted slogans in the languages of the article without indicating the original language.

When comparing the representation of the LL of protests on Latvian, Russian, and European news websites, no significant differences are visible in the approaches to including LL texts in the article and to describing them. Strategies for creating and cultivating other discourses and narratives related to the protests (e.g., the choice of protest dates and march routes, support from Russia and pro-Russian organizations, political fights (see examples 1–3), linguistic rights of minorities, and power) differ, but they are beyond the scope of this article. It should only be noted that neither the content of the LL texts in protests nor the description of protest signage on news websites has changed in connection with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The second part of the article’s aim was related to the main discourses revealed or concealed by descriptions of LL of protests on news websites. The result of content analysis of ONAs shows that there are two dominant narratives, or media repeatedly spread frames of the protests: (1) the Russian community is united and persistent in the fight against the ethnolinguistically unjust education policy pursued by the government, and (2) students, parents, and the Russian community as a whole should have the right to choose which educational program to study at their schools. As we can see, although the education reform affects all minority schools in Latvia, the activists represent the Russian community (at least some part of it) in the protests and speak about the authorities’ unfair targeting of the Russian community in Latvia and the suppression of the Russian language from education. It is natural that online media, when describing the protests, focus their attention on the “issue” of the Russian minority community, which is referred to as the hot potato (Euronews, 2018; in English).

However, the first narrative should be viewed critically. The main participants of the protests are the organizers (political forces) and their supporters (individual pro-Russians), who in most cases are people of the older generation. Thus, the makeup of the participants indicates a lack of unity in the Russian community’s opinion regarding the reform. Most people affected by the reforms barely participated in the protests after 2004 (with exceptions in some protests in 2018), perhaps because, they do not see benefits of protesting, or, as shown by several surveys and studies, the number of parents, students, and teachers who accept the changes and/or see them in positive light is gradually increasing. Students see the transition to the state language more often without emotional aggravation, and they feel morally and linguistically more confident than even their teachers (Hogan-Brun, 2007; Vēbere, 2017; Lazdiņa & Marten, 2021; Anstrate, 2022; Pāvula, 2024). However, both authors of LL texts and journalists have not paid attention to students’ desire and readiness to switch to studying exclusively in Latvian, citing, for example, survey data obtained by the protesters themselves or researchers. Similarly, the LL texts of the protests and their media coverage do not address the teachers’ linguistic competence in Latvian and their professional readiness to continue working in schools. As some online news articles show (e.g., Dēvica, 2022; Ambote, 2023; Spriņģe, 2018), the so-called former minority schools lack teachers to teach various subjects (including Latvian).

Of course, it cannot be denied that protest participants are united in their views on the education reform as a move against the Russian minority and on the preservation of Russian schools in Latvia. They are also united in their verbal condemnation and actions in a situation where someone challenges their opinions. One such case has been recorded, during the 1 May 2018, protest, in which a Latvian nationalistic-minded man (later called drosmīgais latvietis ‘the brave Latvian’ on Latvian national news portals) held up a poster with the message “A guest, an idiot, or an occupier who imposes his/her own language cannot know the language of the country in which s/he lives!” in Latvian. Police intervened when many aggressive protestors started physically pushing the man and tore up the poster (Jauns, 2018; in Latvian). Other protests have passed without ethnic clashes and violence.

According to Nelde’s (1987) assumption, in situations of language conflict, language is only a secondary symbol, since the real origins of conflict relate to other socioeconomic, political, religious, psychological, or historical issues. The protests against minority education reform and their coverage on news portals should be assessed in the broader context of language policy and integration policy (see Section 1), political power, economic influence, and the labor market. Individual placards with such strong labels of Latvia as fascistic and ethnolinguistically totalitarian should be viewed with caution, because these statements also speak of Kremlin propaganda, which maintains the narrative of the Russian minority as victims in post-Soviet countries. LL texts can be (and in many cases are) tools of Russian ideology to incite discontent among the Russian community and incite ethnic hatred. We cannot forget that the Russian language in Latvian education is not only a mean of acquiring school subjects but also a tool of spreading Russian-oriented ideology and narratives through educational materials, a mean to maintain linguistic presence in the nation-state, and a cultural symbol (and controlling tool) with which politicians can buy Russian-speakers’ votes. However, the small impact of the protests on the changes in the educational reform initiated by the government, and laconic and general view of the protests by news portals raise questions about the effectiveness of protests (including LL) as a form of public debates in some sociopolitical settings (Burr et al., 2025, p. 439). The failure to involve experts in the evaluation of protest texts indirectly demonstrates insufficient number of research-based public discussions of language policy and sociolinguistics topics in the media. It seems absurd that protests, which have been taking place regularly with varying intensity for so long, have not been critically evaluated more broadly by trying to understand the role of textual information in the creation and dissemination of certain narratives in society, the thoughts of residents about the protests and the messages expressed in them. But as this paper shows, LL texts can synthesize broad topics such as minority rights, ethnic relations, power, and education accessibility/quality, and this synthesis should be addressed in the following studies as well.

By saying that, the author acknowledge that the article does not cover all possible discourses and does not provide in-depth analysis of the content of LL texts included in ONAs as attachments. The limitations of the article also go towards the methodology. Although 77 ONA is a significant number for the case study, the study most likely did not include all websites with descriptions of protests and illustrative materials (photos/videos with LL texts) from them. The study did not include websites in other languages, for example, other minority languages of Latvia, national languages of neighboring countries, German, French, etc. These and other, perhaps unacknowledged, limitations pave the way for further research. And it is my hope that the article will inspire other LL researchers to look at the representation of LL texts in the media in other sociopolitical contexts.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Websites Included in the Study and Their Brief Description

| Number | Portal | Language | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | TvNet.lv | Latvian | News portals of Latvia’s largest online media group “TvNet” |

| 2. | rus.TvNet.lv | Russian | |

| 3. | Apollo.lv | Latvian | |

| 4. | Delfi.lv | Latvian | News portals of the largest Internet mass media company in the Baltic State “Ekspress Grupp” |

| 5. | rus.delfi.lv | Russian | |

| 6. | Jauns.lv | Latvian | News portal by “Rīgas Viļņi”, the second biggest Latvian publishing house |

| 7. | Diena.lv | Latvian | News portal of "Diena", one of the largest daily newspapers in Latvia |

| 8. | Nra.lv | Latvian | Digital daily news newspaper with nationalistic political orientation |

| 9. | Leta.lv | Latvian | News portal by the main Latvian national news agency “Leta” owned by Estonian company “Postimees Group” |

| 10. | Ir.lv | Latvian | News portal by independent media company “Cits medijs” |

| 11. | LSM.lv | Latvian | Latvian Broadcasting Corporation’s (Latvijas Sabiedriskie Mediji, or LSM, in Latvian) internet platforms |

| 12. | eng.LSM.lv | English | |

| 13. | rus.LSM.lv | Russian | |

| 14. | la.lv | Latvian | News portal by “Latvijas Mediji”, one of the largest periodical and book publishers in Latvia |

| 15. | ziņas.tv3.lv | Latvian | News portal by the commercial media agency “All Media Latvia” |

| 16. | Baltictimes.com | English | International online newspaper covering all the Baltic states |

| 17. | Politico.eu | English | European news portal covering politics, policy, and personalities of EU |

| 18. | Euronews.com | English | International news portal in the EU |

| 19. | ru.euronews.com | Russian | |

| 20. | bbc.com | English | News portal by “BBC”, or British Broadcasting Corporation, a public British broadcasting company that operates under a royal charter |

| 21. | euractiv.com | English | European news portal, seen as one of the most influential EU sources |

| 22. | rus.postimees.ee | Russian | Russian-language version of the portal “Postimees”, the oldest news provider in Estonia |

| 23. | russkije.lv | Russian | Informative non-commercial website about Russians living in Latvia |

| 24. | news.ru | Russian | Russian independent online news portal generally critical of the Russian government; unactive |

| 25. | dailystorm.ru | Russian | Russian news portal |

| 26. | gazeta.ru | Russian | Russian news site based in Moscow |

| 27. | lv.sputniknews.ru | Russian | News portal by Russian news agency “Sputnik” internationally criticized for spreading fake news, disinformation, and Russian propaganda |

| 28. | lv.baltnews.com | Russian | News portal in the Baltic states published by the Russian news agency “Baltnews”, considered to be a Kremlin-owned “mouthpiece of Russian propaganda” media |

| 29. | tass.com | English | Website by Russian-state owned news agency, the largest Russian news agency and of the biggest international information agencies, cited as a source of disinformation |

Note

| 1 | All translations from Latvian and Russian into English are done by the author. |

References