Exploring Students’ Perceptions of the Campus Climate and Intergroup Relations: Insights from a Campus-Wide Survey at a Minority-Serving University

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How do students at a Minority-Serving Institution perceive the inclusiveness of their campus climate in relation to their identities?

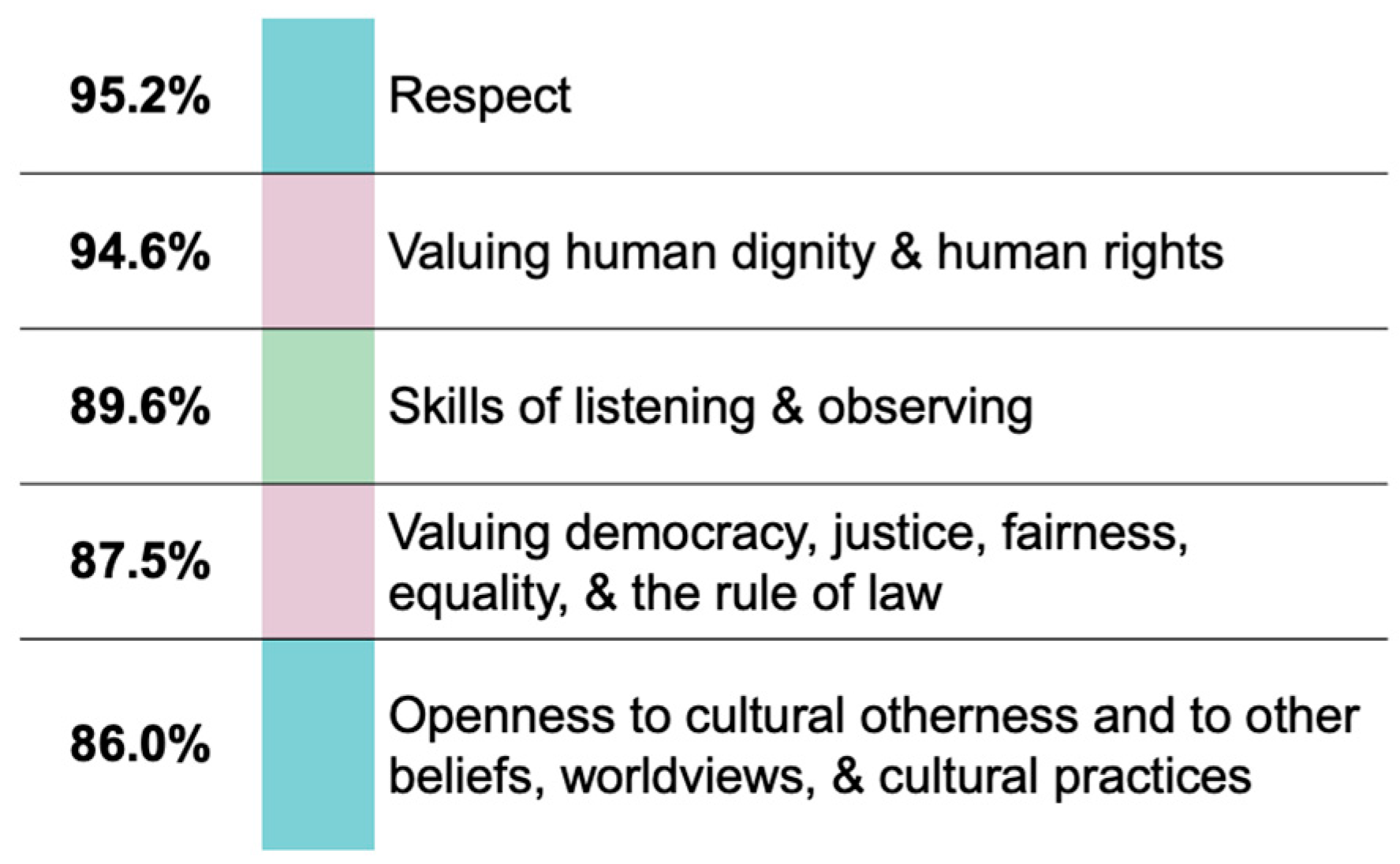

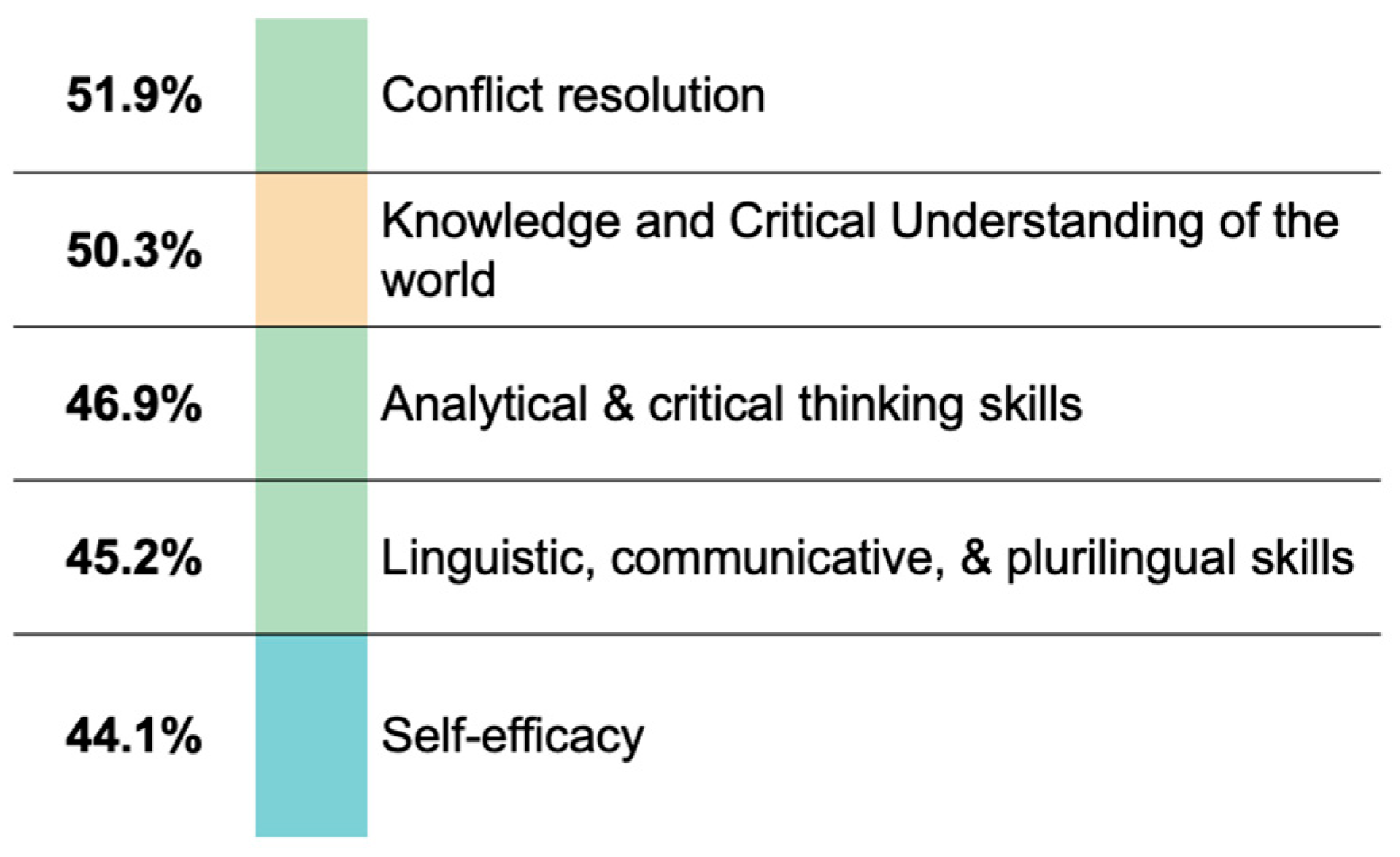

- Which VASK competences do students consider important, and which have they had opportunities to develop?

- How do students’ intergroup friendships and engagement in campus activities relate to their perceived sense of belonging?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Intergroup Relations and Campus Climate

2.2. Intercultural Communication and Competences for Democratic Culture

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Method

3.2. Variables

3.3. Intergroup Relations Variables

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Perceptions and Experiences of Diversity and Inclusion at the Minority-Serving Institution

4.2. Comfortable Spaces for Discussing Topics Related to Students’ Identities

4.3. Comfortable Spaces for Discussing Topics of Worldview and Beliefs

4.4. Friendship Dynamics

4.5. Student Involvement in Campus Social Activities

4.6. Institutional Opportunities for Experiencing the VASK Areas

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- -

- Very diverse (4)

- -

- Somewhat diverse (3)

- -

- Somewhat lacking diversity (2)

- -

- Not diverse at all (1).

- -

- Very inclusive (4)

- -

- Somewhat inclusive (3)

- -

- Somewhat lacking inclusiveness (2)

- -

- Not inclusive at all (1).

- -

- Agree (4)

- -

- Somewhat agree (3)

- -

- Somewhat disagree (2)

- -

- Disagree (1).

- -

- Agree (4)

- -

- Somewhat agree (3)

- -

- Somewhat disagree (2)

- -

- Disagree (1).

- -

- Agree (4)

- -

- Somewhat agree (3)

- -

- Somewhat disagree (2)

- -

- Disagree (1)

- -

- Agree (4)

- -

- Somewhat agree (3)

- -

- Somewhat disagree (2)

- -

- Disagree (1)

- -

- Agree (4)

- -

- Somewhat agree (3)

- -

- Somewhat disagree (2)

- -

- Disagree (1)

- -

- Classrooms (face-to-face)

- -

- Classrooms (virtual)

- -

- Residence Halls

- -

- Student organizations

- -

- During on-campus celebrations, festivals

- -

- With close friends

- -

- With faculty

- -

- With staff

- -

- Other, please add:

- -

- None.

- -

- Classrooms (face-to-face)

- -

- Classrooms (virtual)

- -

- Residence Halls

- -

- Student organizations

- -

- During on-campus celebrations, festivals

- -

- With close friends

- -

- With faculty

- -

- With staff

- -

- Other, please add:

- -

- None.

| Very Important (4) | Moderately Important (3) | Slightly Important (2) | Not Important at All (1) | |

| Valuing human dignity and human rights | ||||

| Valuing cultural diversity | ||||

| Valuing democracy, justice, fairness, equality, and the rule of law |

| Very Important (4) | Moderately Important (3) | Slightly Important (2) | Not Important at All (1) | |

| Openness to cultural otherness and to other beliefs, worldviews, and cultural practices | ||||

| Respect | ||||

| Civic-mindedness | ||||

| Responsibility | ||||

| Self-efficacy | ||||

| Tolerance of ambiguity |

| Very Important (4) | Moderately Important (3) | Slightly Important (2) | Not Important at All (1) | |

| Autonomous learning skills (i.e., independent learning skills) | ||||

| Analytical and critical thinking skills | ||||

| Skills of listening and observing | ||||

| Empathy | ||||

| Flexibility and adaptability | ||||

| Linguistic, communicative, and plurilingual skills | ||||

| Cooperation skills | ||||

| Conflict-resolution skills |

| Very Important (4) | Moderately Important (3) | Slightly Important (2) | Not Important at All (1) | |

| Knowledge and critical understanding of the self | ||||

| Knowledge and critical understanding of language and communication | ||||

| Knowledge and critical understanding of the world: politics, human rights, culture in general, cultures, religions, history, media, economics, environment, and sustainability |

- -

- Valuing human dignity and human rights

- -

- Valuing cultural diversity

- -

- Valuing democracy, justice, fairness, equality, and the rule of law

- -

- Openness to cultural otherness, to other cultural beliefs, practices, and worldviews

- -

- Respect

- -

- Civic-mindedness

- -

- Responsibility

- -

- Self-efficacy

- -

- Tolerance of ambiguity

- -

- Autonomous learning skills

- -

- Analytical and critical thinking skills

- -

- Listening and observing skills

- -

- Empathy

- -

- Flexibility and adaptability

- -

- Linguistic, communicative, and plurilingual skills

- -

- Cooperation skills

- -

- Conflict-resolution skills

- -

- Knowledge and critical understanding of the self

- -

- Knowledge and critical understanding of language and communication

- -

- Knowledge and critical understanding of the world: politics, law, human rights, culture, cultures, religions, history, media, economies, environment, and sustainability

- -

- None.

- -

- Valuing human dignity and human rights

- -

- Valuing cultural diversity

- -

- Valuing democracy, justice, fairness, equality, and the rule of law

- -

- Openness to cultural otherness, to other cultural beliefs, practices, and worldviews

- -

- Respect

- -

- Civic-mindedness

- -

- Responsibility

- -

- Self-efficacy

- -

- Tolerance of ambiguity

- -

- Autonomous learning skills

- -

- Analytical and critical thinking skills

- -

- Listening and observing skills

- -

- Empathy

- -

- Flexibility and adaptability

- -

- Linguistic, communicative, and plurilingual skills

- -

- Cooperation skills

- -

- Conflict-resolution skills

- -

- Knowledge and critical understanding of the self

- -

- Knowledge and critical understanding of language and communication

- -

- Knowledge and critical understanding of the world: politics, law, human rights, culture, cultures, religions, history, media, economies, environment, sustainability

- -

- None.

| Friend 1 | Friend 2 | Friend 3 | |

| Speaks the same first (native) language as me | |||

| Has the same ethno-racial background as myself | |||

| Identifies with the same religious or spiritual group/belief system as I do | |||

| Identifies with the same sexual orientation as I do | |||

| Is from the same country as I am |

- -

- One

- -

- Two

- -

- Three

- -

- Four or more

- -

- I have not joined a student organization, club, or society at my university.

- -

- Academic/Departmental

- -

- Governance

- -

- Honors and Recognition

- -

- Service and Social Action

- -

- Arts and Media

- -

- Fraternity and Sorority

- -

- Intellectual Sports

- -

- Sports and Recreation

- -

- Career and Professional

- -

- Health and Wellness

- -

- Politics

- -

- For Graduate Students

- -

- Cultural and Ethnic

- -

- Hobbies and Interests

- -

- Religion and Beliefs

- -

- For Faculty and Staff

- -

- Other, please specify:

- -

- None.

References

- Allport, G. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, M., Aceska, N., Azzouz, N., Bar, C., Baytelman, A., Cenci, S., Chushak, K., Clifford, A., Dautaj, A., Filippov, V., Fursa, I., Gebauer, B., Gozuyasli, N., Larraz, V., Mehdiyeva, N., Mihail, R., Soivio, N., Paaske, N., Ranonyte, A., … Valečić, H. (2021). Assessing competences for democratic culture: Principles, methods, examples. Council of Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, M., & Golubeva, I. (2022). From intercultural communicative competence to intercultural citizenship: Preparing young people for citizenship in a culturally diverse democratic world. In T. McConachy, I. Golubeva, & M. Wagner (Eds.), Intercultural learning in language education and beyond: Evolving concepts, perspectives and practices (pp. 60–83). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. (2016). Competences for democratic culture: Living together as equals in culturally diverse democratic societies. Council of Europe Publishing. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/16806ccc07 (accessed on 1 January 2019).

- Council of Europe. (2018). Reference framework of competences for democratic culture (3 Vols.). Council of Europe Publishing. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/reference-framework-of-competences-for-democratic-culture/rfcdc-volumes (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Cuellar, M. G., & Johnson-Ahorlu, R. N. (2020). Racialized experiences off and on campus: Contextualizing latina/o students’ perceptions of climate at an emerging Hispanic-serving institution (HSI). Urban Education, 58(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deardorff, D. K. (2004). The identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of international education at institutions of higher education in the United States [Unpublished dissertation, North Carolina State University]. [Google Scholar]

- Fantini, A. E., & Tirmizi, A. (2006). Exploring and assessing intercultural competence. World Learning Publications, Paper 1. Available online: http://digitalcollections.sit.edu/worldlearning_publications/1 (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- Garvey, J. C., Squire, D. D., Stachler, B., & Rankin, S. (2018). The impact of campus climate on queer-spectrum student academic success. Journal of LGBT Youth, 15(2), 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavino, M. C., & Akinlade, E. (2021). The effect of diversity climate on institutional affiliation/pride and intentions to stay and graduate: A comparison of latinx and non-latinx white students. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 20(1), 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubeva, I. (2025a). Digital humanities pedagogy in action: Insights from intercultural telecollaboration exploring inclusiveness of university campuses through art. Language and Intercultural Communication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubeva, I. (2025b). Diversity, equity, inclusion and intercultural citizenship in higher education. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, R. L., Wolfeld, L., Armon, B. K., Rios, J., & Liu, O. L. (2016). Assessing intercultural competence in higher education: Existing research and future directions. ETS Research Report Series, 2016(2), 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, S. R., & Hurtado, S. (2007). Nine themes in campus racial climates and implications for institutional transformation. In S. R. Harper, & L. D. Patton (Eds.), Responding to the realities of race on campus (No. 120, pp. 7–24). New directions for student services. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J., & Fellabaum, J. (2008). Analyzing campus climate studies: Seeking to define and understand. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 1(4), 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, T. D., Rockenbach, A. N., Mayhew, M. J., & Zhang, L. (2021). Examining the relationship between college students’ interworldview friendships and pluralism orientation. Teachers College Record, 123, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, S., Alvarez, C. L., Guillermo-Wann, C., Cuellar, M., & Arellano, L. (2012). A model for diverse learning environments: The scholarship on creating and assessing conditions for student success. In J. C. Smart, & M. B. Paulsen (Eds.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (pp. 41–122). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado, S., Griffin, K. A., Arellano, L., & Cuellar, M. (2008). Assessing the value of climate assessments: Progress and future directions. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 1(4), 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, S., Milem, J. F., Clayton-Pedersen, A. R., & Allen, W. R. (1999). Enacting diverse learning environments: Improving the campus climate for racial/ethnic diversity. ASHE/ERIC Higher Education Reports, 26, 1–140. [Google Scholar]

- International Consortium for Higher Education, Civic Responsibility, and Democracy. (2019). Declaration: Global forum on academic freedom, institutional autonomy, and the future of democracy. Available online: https://www.internationalconsortium.org/declaration/ (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Jean-Francois, E. (2019). Exploring the perceptions of campus climate and integration strategies used by international students in a US university campus. Studies in Higher Education, 44(6), 1069–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarsfeld, P. F., & Merton, R. K. (1954). Friendship as a social process: A substantive and methodological analysis. In M. Berger, T. Abel, & C. H. Page (Eds.), Freedom and control in modern society (pp. 18–66). Van Nostrand. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, I., Song, W., Schulzetenberg, A., Furco, A., & Maruyama, G. (2018). Exploring the relationship between service-learning and perceptions of campus climate. In K. M. Soria (Ed.), Evaluating campus climate at US research universities (pp. 471–486). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Lundy-Wagner, V., & Winkle-Wagner, R. (2013). A harassing climate? Sexual harassment and campus racial climate research. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 6(1), 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maramba, D. C., & Museus, S. D. (2011). The utility of using mixed-methods and intersectionality approaches in conducting research on Filipino American students’ experiences with the campus climate and on sense of belonging. New Directions for Institutional Research, 2011(151), 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milem, J. F., Chang, M. J., & Antonio, A. L. (2005). Making diversity work on campus: A research-based perspective. Association of American Colleges & Universities. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, K. J. (2021). Black students’ perceptions of campus climates and the effect on academic resilience. Journal of Black Psychology, 47(4–5), 354–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. B., Bishop, K., & Etmanski, C. (2021). Community belonging and values-based leadership as the antidote to bullying and incivility. Societies, 11(29). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrum, W., Cheek, N. H., Jr., & MacD. Hunter, S. (1988). Friendship in school: Gender and racial homophily. Sociology of Education, 61(4), 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria, K. M. (Ed.). (2018). Evaluating campus climate at US research universities. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Ting-Toomey, S., & Dorjee, T. (2015). Intercultural and intergroup communication competence: Toward an integrative perspective. Communication Competence, 20, 503–538. [Google Scholar]

- Tuma, N. B., & Hallinan, M. T. (1979). The effects of sex, race, and achievement on schoolchildren’s friendships. Social Forces, 57(4), 1265–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2013). Intercultural competences: Conceptual and operational framework. UNESCO. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002197/219768e.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2023).

- Vega, B. E. (2021). “What is the real belief on campus?”: Perceptions of racial conflict at a minority-serving institution and a historically white institution. Teachers College Record, 123(9), 144–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodard, V. S., & Sims, J. M. (2000). Programmatic approach to improving campus climate. Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice, 37(4), 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, D. (2024). Multidimensional homophily. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 218, 486–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Degree Type | ||

| Bachelor’s | 70.9 | |

| Master’s | 15.9 | |

| Doctoral | 10.2 | |

| First-Generation Student | 24.6 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Asian | 28.5 | |

| Black/African American | 19.6 | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 8.9 | |

| Two or more races | 5.4 | |

| White | 35.5 | |

| Gender Identity | ||

| Female | 58.0 | |

| Male | 36.0 | |

| Other | 6.0 | |

| College | ||

| CAHSS | 38.5 | |

| CoEIT | 32.3 | |

| CNMS | 29.3 | |

| Aging studies | <1 | |

| Public policy | 3.4 | |

| Social work | 2.1 | |

| Academic Level | ||

| Freshman | 20.7 | |

| Sophomore | 15.5 | |

| Junior | 17.7 | |

| Senior | 21.5 | |

| Graduate | 24.6 | |

| Languages Spoken | ||

| One | 46.1 | |

| Two | 35.6 | |

| Three | 14.4 | |

| Four or more languages | 3.9 | |

| M | SD | |

| Age | 24.41 | 1.91 |

| I Experience ___ as a Community That Is Inclusive of My Ethno-Racial Identity. | I Experience ___ as a Community That Is Inclusive of My Gender Identity. | I Experience ___ as a Community That Is Inclusive of My Sexual Orientation. | I Experience ___ as a Community That Is Inclusive of My Religious/Spiritual Beliefs. | I Experience ___ as a Community That Is Inclusive of My Ideological Worldviews. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman’s rho | Degree level | Correlation coefficient | −0.021 | −0.079 * | −0.055 | −0.013 | −0.018 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.554 | 0.024 | 0.118 | 0.718 | 0.600 | ||

| N | 820 | 820 | 820 | 820 | 820 | ||

| First in family to attend a 4-year college | Correlation coefficient | 0.079 * | 0.013 | 0.087 * | −0.040 | 0.017 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.024 | 0.702 | 0.013 | 0.248 | 0.617 | ||

| N | 820 | 820 | 820 | 820 | 820 | ||

| Ethnicity | Correlation coefficient | −0.084 * | 0.019 | 0.006 | −0.104 ** | −0.036 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.016 | 0.581 | 0.872 | 0.003 | 0.306 | ||

| N | 818 | 818 | 818 | 818 | 818 | ||

| Age range | Correlation coefficient | 0.017 | −0.047 | −0.041 | 0.010 | 0.017 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.623 | 0.175 | 0.241 | 0.775 | 0.623 | ||

| N | 820 | 820 | 820 | 820 | 820 | ||

| Gender identity | Correlation coefficient | −0.007 | 0.055 | 0.057 | −0.064 | 0.039 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.849 | 0.115 | 0.103 | 0.066 | 0.263 | ||

| N | 820 | 820 | 820 | 820 | 820 | ||

| Languages spoken | Correlation coefficient | 0.091 ** | 0.029 | 0.014 | 0.044 | 0.006 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.009 | 0.404 | 0.683 | 0.205 | 0.867 | ||

| N | 820 | 820 | 820 | 820 | 820 |

| Total Scores | −0.125 ** | <0.001 | 820 | −0.084 * | 0.016 | 820 | 0.101 ** | 0.004 | 818 | −0.136 ** | <0.001 | 820 | 0.000 | 0.989 | 820 | −0.030 | 0.396 | 820 |

| None | 0.082 * | 0.019 | 820 | 0.067 | 0.056 | 820 | −0.011 | 0.750 | 818 | 0.091 ** | 0.009 | 820 | 0.045 | 0.202 | 820 | 0.003 | 0.943 | 820 |

| Other | 0.117 ** | <0.001 | 820 | −0.092 ** | 0.009 | 820 | 0.048 | 0.173 | 818 | 0.117 ** | <0.001 | 820 | −0.006 | 0.868 | 820 | −0.042 | 0.227 | 820 |

| With staff | −0.027 | 0.442 | 820 | −0.021 | 0.556 | 820 | 0.090 * | 0.010 | 818 | −0.014 | 0.683 | 820 | −0.013 | 0.713 | 820 | −0.030 | 0.384 | 820 |

| With faculty | 0.019 | 0.592 | 820 | −0.012 | 0.724 | 820 | 0.131 ** | <0.001 | 818 | 0.076 * | 0.029 | 820 | 0.008 | 0.816 | 820 | −0.038 | 0.279 | 820 |

| With friends | −0.172 ** | <0.001 | 820 | −0.076 * | 0.031 | 820 | 0.042 | 0.230 | 818 | −0.222 ** | <0.001 | 820 | −0.065 | 0.063 | 820 | −0.005 | 0.885 | 820 |

| Campus celebrations/festivals | −0.065 | 0.065 | 820 | −0.067 | 0.056 | 820 | −0.041 | 0.243 | 818 | −0.104 ** | 0.003 | 820 | −0.048 | 0.171 | 820 | 0.062 | 0.077 | 820 |

| Student organizations | −0.160 ** | <0.001 | 820 | −0.039 | 0.260 | 820 | 0.020 | 0.561 | 818 | −0.209 ** | <0.001 | 820 | 0.023 | 0.516 | 820 | −0.005 | 0.885 | 820 |

| Residence halls | −0.219 ** | <0.001 | 820 | −0.118 ** | <0.001 | 820 | 0.020 | 0.562 | 818 | −0.289 ** | <0.001 | 820 | 0.037 | 0.293 | 820 | −0.021 | 0.547 | 820 |

| Virtual classrooms | −0.007 | 0.832 | 820 | −0.062 | 0.077 | 820 | 0.079 * | 0.023 | 818 | 0.058 | 0.098 | 820 | 0.011 | 0.759 | 820 | −0.039 | 0.261 | 820 |

| Classrooms | −0.063 | 0.071 | 820 | −0.020 | 0.565 | 820 | 0.120 ** | <0.001 | 818 | −0.072 * | 0.039 | 820 | 0.066 | 0.057 | 820 | −0.048 | 0.173 | 820 |

| r | Sig (2−tailed) | N | r | Sig (2−tailed) | N | r | Sig (2−tailed) | N | r | Sig (2−tailed) | N | r | Sig (2−tailed) | N | r | Sig (2−tailed) | N | |

| Degree level | First generation | Ethnicity | Age range | Gender identity | Languages spoken | |||||||||||||

| Spearman’s rho | ||||||||||||||||||

| Total Scores | −0.076 * | 0.029 | 820 | −0.088 * | 0.012 | 820 | 0.118 ** | <0.001 | 818 | −0.073 * | 0.037 | 820 | −0.007 | 0.852 | 820 | −0.032 | 0.353 | 820 |

| None | 0.008 | 0.816 | 820 | 0.114 ** | 0.001 | 820 | −0.053 | 0.133 | 818 | 0.021 | 0.552 | 820 | 0.053 | 0.127 | 820 | 0.003 | 0.925 | 820 |

| Other | 0.155 ** | <0.001 | 820 | −0.052 | 0.138 | 820 | 0.030 | 0.385 | 818 | 0.103 ** | 0.003 | 820 | −0.033 | 0.350 | 820 | −0.024 | 0.489 | 820 |

| With staff | 0.023 | 0.509 | 820 | 0.002 | 0.947 | 820 | 0.091 ** | 0.009 | 818 | 0.028 | 0.427 | 820 | −0.014 | 0.698 | 820 | −0.014 | 0.692 | 820 |

| With faculty | 0.022 | 0.525 | 820 | −0.018 | 0.604 | 820 | 0.136 ** | <0.001 | 818 | 0.060 | 0.086 | 820 | 0.014 | 0.684 | 820 | −0.041 | 0.239 | 820 |

| With friends | −0.146 ** | <0.001 | 820 | −0.088 * | 0.012 | 820 | 0.064 | 0.068 | 818 | −0.181 ** | <0.001 | 820 | −0.061 | 0.079 | 820 | −0.040 | 0.254 | 820 |

| Campus celebrations/festivals | −0.035 | 0.316 | 820 | −0.075 * | 0.031 | 820 | 0.013 | 0.703 | 818 | −0.108 ** | 0.002 | 820 | −0.002 | 0.954 | 820 | 0.043 | 0.220 | 820 |

| Student organizations | −0.167 ** | <0.001 | 820 | −0.078 * | 0.026 | 820 | 0.029 | 0.413 | 818 | −0.206 ** | <0.001 | 820 | 0.006 | 0.875 | 820 | −0.016 | 0.641 | 820 |

| Residence halls | −0.186 ** | <0.001 | 820 | −0.135 ** | <0.001 | 820 | 0.102 ** | 0.003 | 818 | −0.226 ** | <0.001 | 820 | 0.061 | 0.079 | 820 | −0.064 | 0.069 | 820 |

| Virtual classrooms | 0.003 | 0.936 | 820 | −0.036 | 0.307 | 820 | 0.082 * | 0.019 | 818 | 0.111 * | 0.002 | 820 | −0.014 | 0.686 | 820 | −0.020 | 0.560 | 820 |

| Classrooms | −0.029 | 0.410 | 820 | −0.037 | 0.285 | 820 | 0.101 ** | 0.004 | 818 | 0.006 | 0.861 | 820 | 0.087 * | 0.013 | 820 | −0.031 | 0.378 | 820 |

| r | Sig (2−tailed) | N | r | Sig (2−tailed) | N | r | Sig (2−tailed) | N | r | Sig (2−tailed) | N | r | Sig (2−tailed) | N | r | Sig (2−tailed) | N | |

| Degree level | First generation | Ethnicity | Age range | Gender identity | Languages spoken | |||||||||||||

| Spearman’s rho | ||||||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Golubeva, I.; Di Maria, D.; Holden, A.; Kohler, K.; Wade, M.E. Exploring Students’ Perceptions of the Campus Climate and Intergroup Relations: Insights from a Campus-Wide Survey at a Minority-Serving University. Journal. Media 2025, 6, 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030111

Golubeva I, Di Maria D, Holden A, Kohler K, Wade ME. Exploring Students’ Perceptions of the Campus Climate and Intergroup Relations: Insights from a Campus-Wide Survey at a Minority-Serving University. Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(3):111. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030111

Chicago/Turabian StyleGolubeva, Irina, David Di Maria, Adam Holden, Katherine Kohler, and Mary Ellen Wade. 2025. "Exploring Students’ Perceptions of the Campus Climate and Intergroup Relations: Insights from a Campus-Wide Survey at a Minority-Serving University" Journalism and Media 6, no. 3: 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030111

APA StyleGolubeva, I., Di Maria, D., Holden, A., Kohler, K., & Wade, M. E. (2025). Exploring Students’ Perceptions of the Campus Climate and Intergroup Relations: Insights from a Campus-Wide Survey at a Minority-Serving University. Journalism and Media, 6(3), 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030111