Anti-Sustainability Narratives in Chat Apps: What Shapes the Brazilian Far-Right Discussion About Socio-Environmental Issues on WhatsApp and Telegram

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

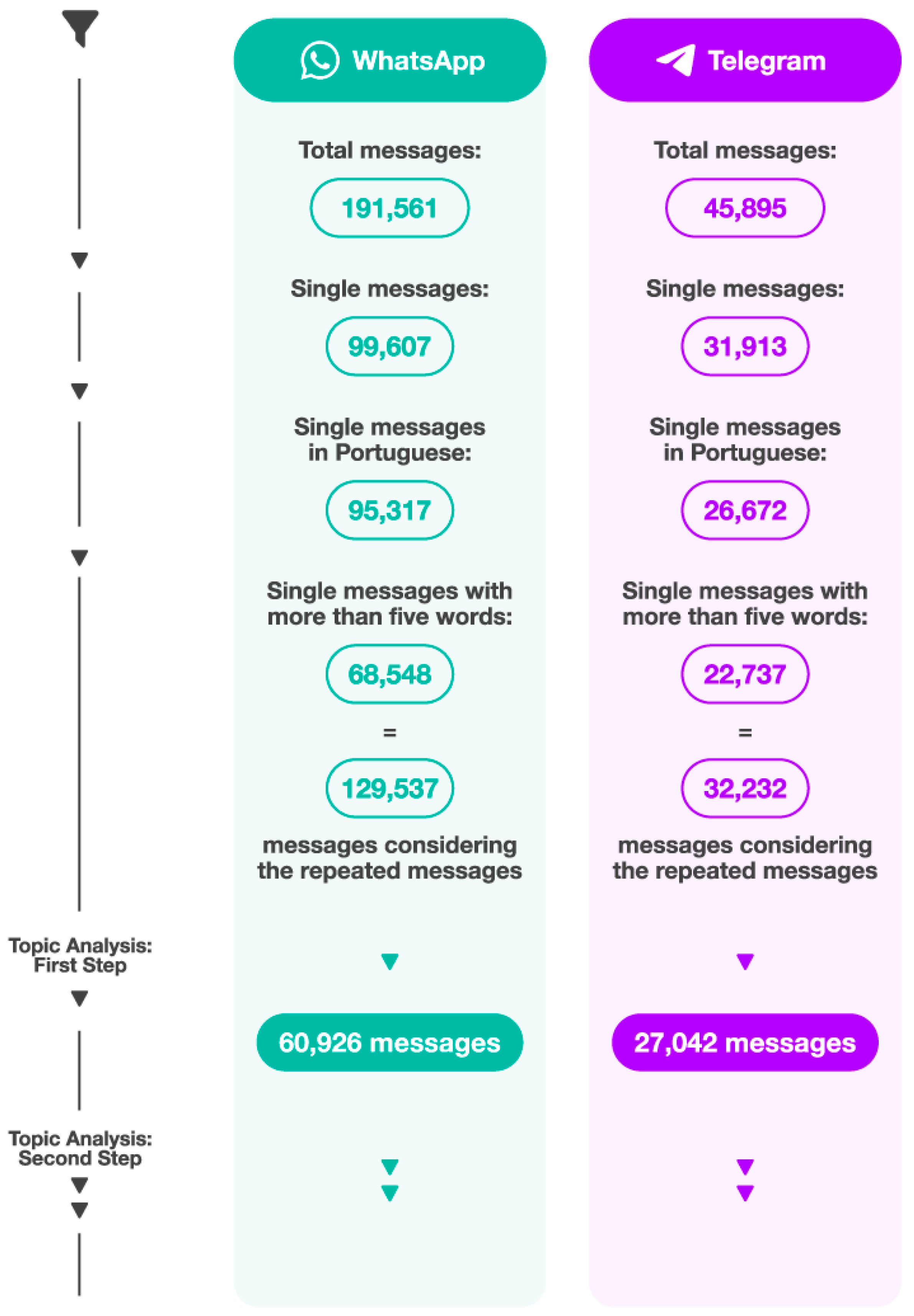

3. Materials and Methods

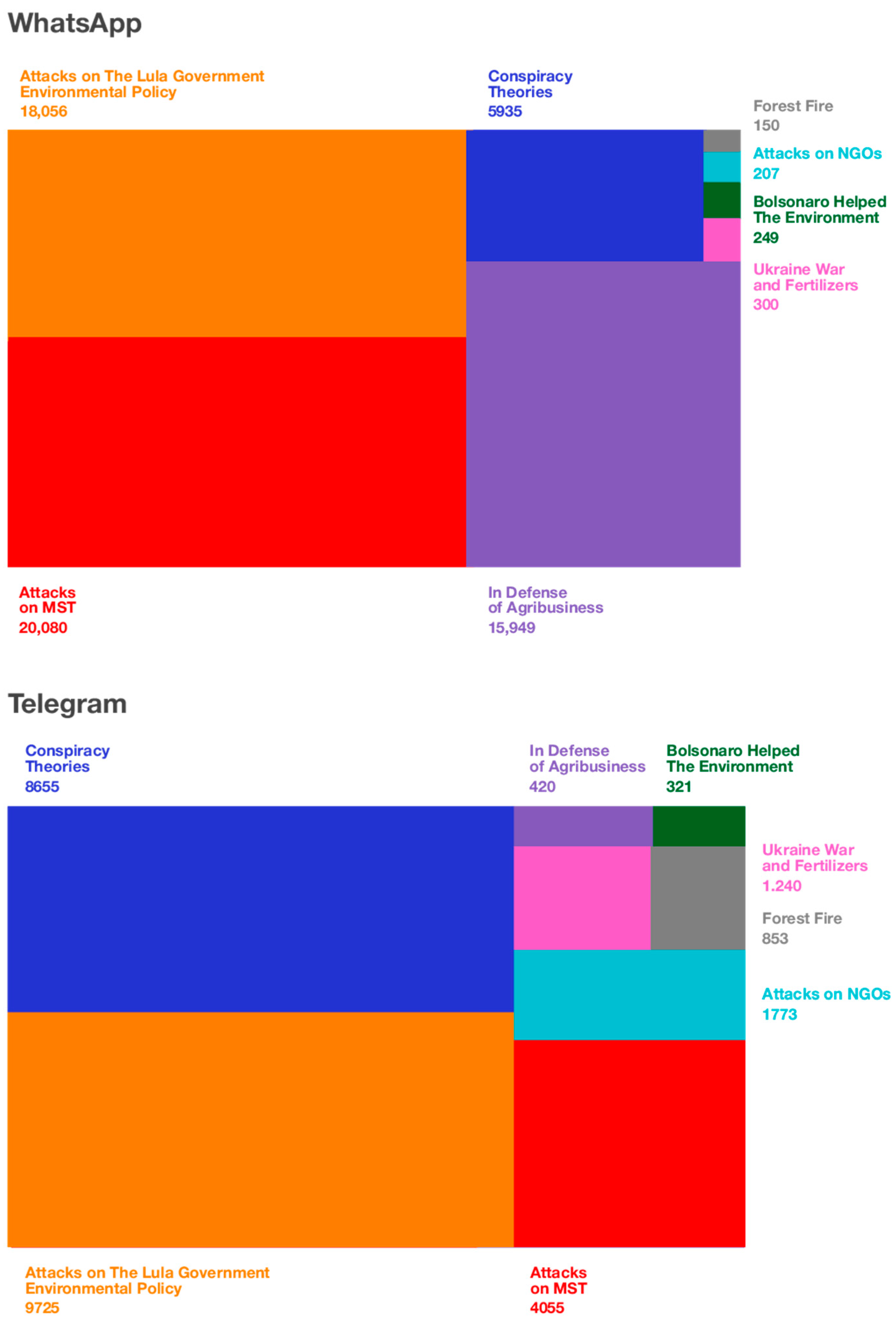

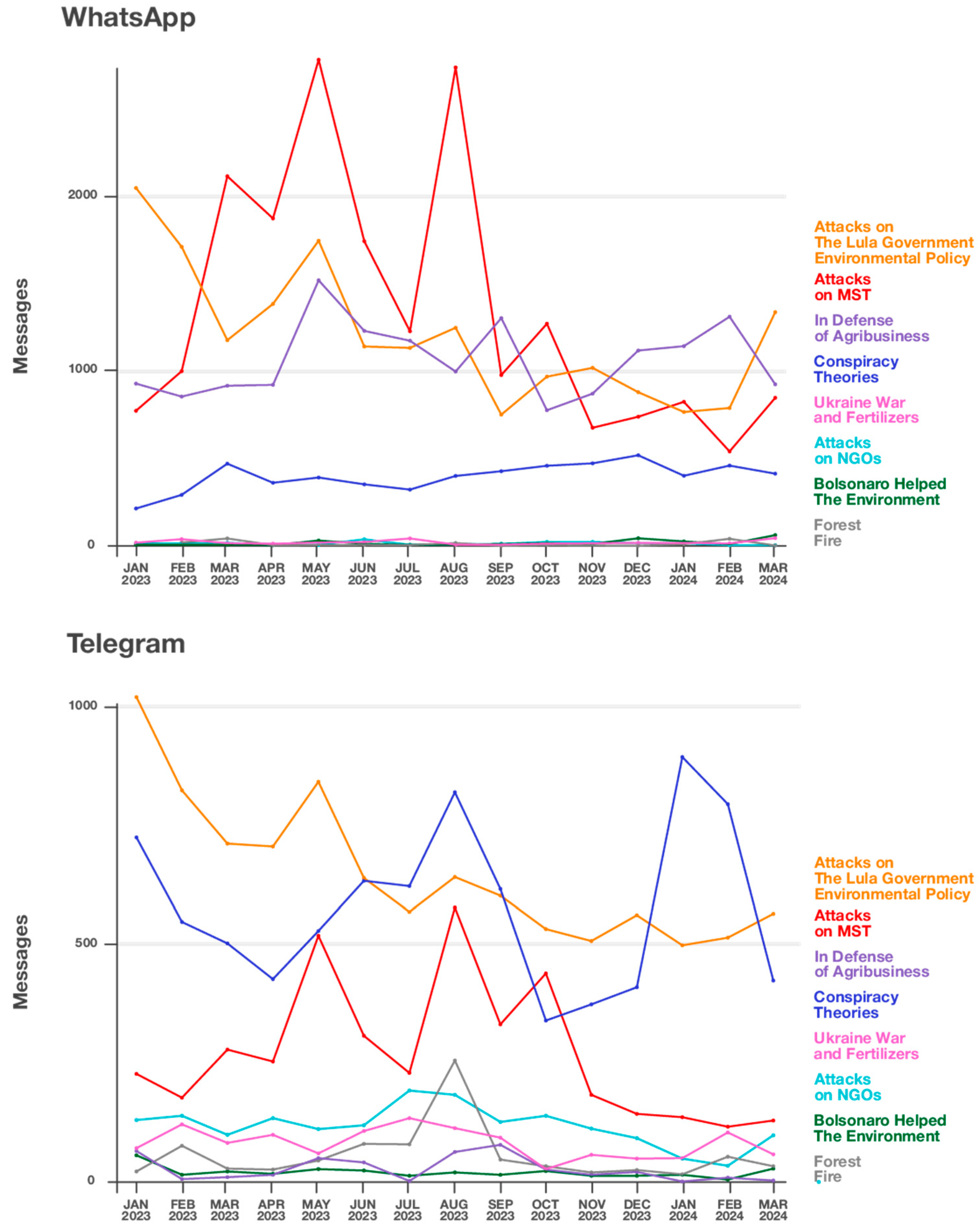

4. Results and Discussion

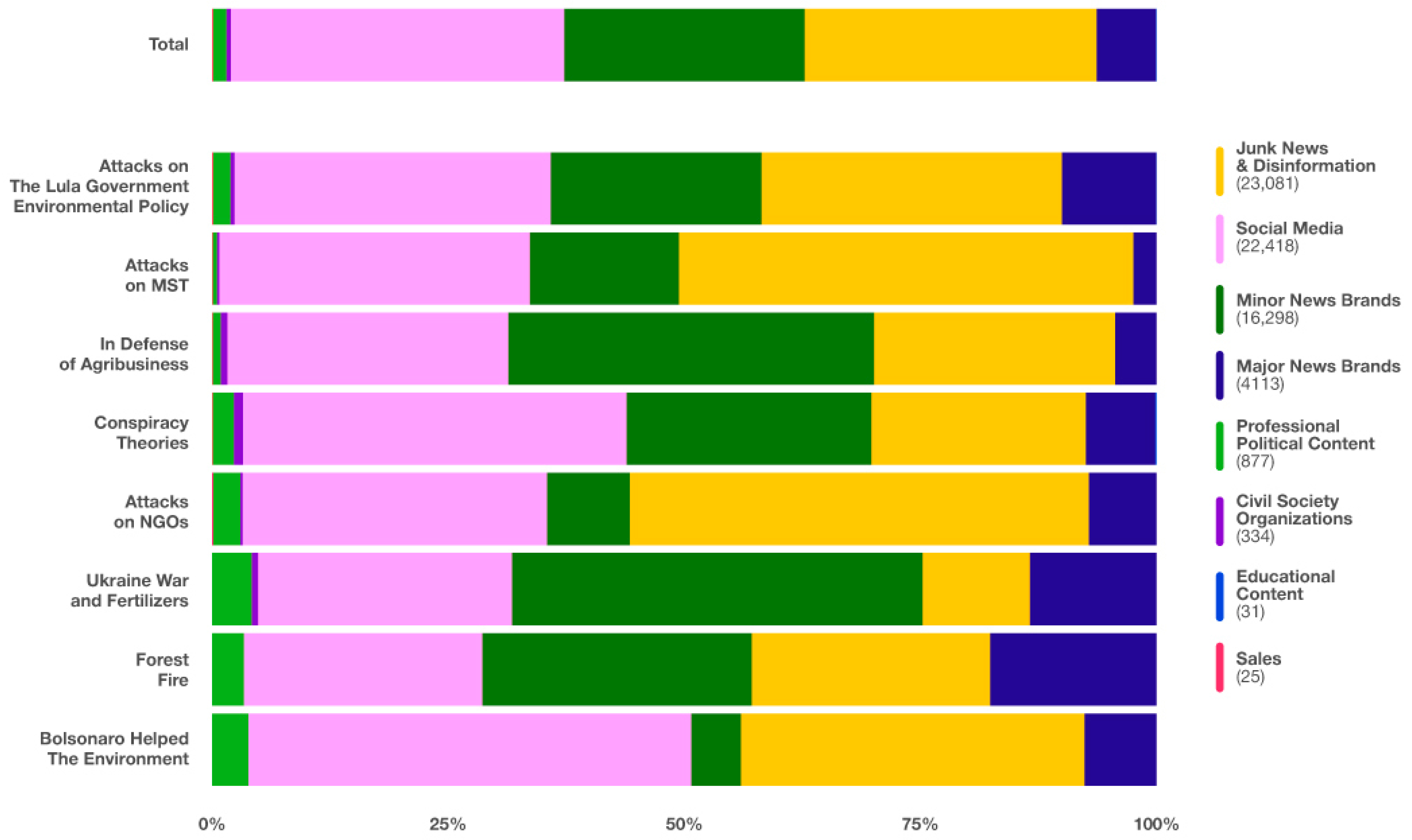

Disinformation and the Social Media Ecosystem

5. Final Considerations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alentejano, P. (2020). A hegemonia do agronegócio e a reconfiguração da luta pela terra e reforma agrária no brasil. Caderno Prudentino De Geografia, 4(42), 251–285. Available online: https://revista.fct.unesp.br/index.php/cpg/article/view/7763 (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Alvisi, L., Tardelli, S., & Tesconi, M. (2024, September 2–5). Unraveling the Italian and English telegram conspiracy spheres through message forwarding. Social Networks Analysis and Mining: 16th International Conference, ASONAM 2024 (pp. 204–213), Rende, Italy. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APIB. (n.d.). Marco temporal|APIB. APIB oficial. Available online: https://apiboficial.org/marco-temporal/ (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Araujo, D. (2020). A Atuação das Organizações não Governamentais (ONG’s) na Proteção do Meio Ambiente na Amazônia. CAMPO JURÍDICO, 8, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assahira, C., & Moretto, E. M. (2024). A degradação da Amazônia e a dimensão ambiental da crise da democracia no Brasil. Novos Cadernos NAEA, 27(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badullovich, N., Grant, W., & Colvin, R. (2020). Framing climate change for effective communication: A systematic map. Environmental Research Letters, 15(12), 123002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernath, A. (2023). Por que governo Bolsonaro é investigado por suspeita de genocídio contra os yanomami. BBC News Brasil. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/brasil-64417930 (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Birss, M. (2017). Criminalizing environmental activism: As threats to the environment increase across Latin America, new laws and police practices take aim against the front line activists defending their land and resources. NACLA Report on the Americas, 49(3), 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt, T. P., Romano, J. O., & Castilho, A. C. A. S. (2022). O discurso político do agronegócio. Revista Tamoios, 18(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, P. (2014). The hyperlinked world: A look at how the interactions of news frames and hyperlinks influence news credibility and willingness to seek information. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 19(3), 576–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, R. (2024, January 8). Brazil marks anniversary of Jan. 8 attack on democracy. Reuters. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/brazil-mark-anniversary-january-8-attack-democracy-2024-01-08/ (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Bruno, R. (2021). Frente Parlamentar da Agropecuária (FPA): Campo de disputa entre ruralistas e petistas no Congresso Nacional brasileiro. Estudos Sociedade e Agricultura, 29(2), 461–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budó, M. D. N. (2017). A mortes no campo e a operação greenwashing do “agro”: Invisibilização de danos sociais massivos no Brasil. InSURgência: Revista de Direitos e Movimentos Sociais, 3(2), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, M. J. (2019). Denial and deception. In M. J. Bush (Org.), Climate change and renewable energy: How to end the climate crisis (pp. 373–420). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CAAD. (n.d.). What is misinformation & disinformation. Climate action against disinformation. Available online: https://caad.info/what-is-misinformation-disinformation/ (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Calvo-Gutiérrez, E., & Marín-Lladó, C. (2023). Combatting fake news: A global priority post COVID-19. Societies, 13(7), 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, R. D. E., Barcelos, S. B., & Severo, R. G. (2024). Conspiracy theories and anti-environmentalism in Bolsonaro’s Brazil. In I. K. Allen, K. Ekberg, S. Holgersen, & A. Malm (Eds.), Political ecologies of the far right: Fanning the flames (pp. 174–194). Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M. (2015). Challenging social inequality: The landless rural workers movement and agrarian reform in Brazil. Duke University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CGEE. (2024). Public perception of S&T in Brazil—2023. Centro de Gestão e Estudos Estratégicos. Available online: https://static.poder360.com.br/2024/05/percepcao-ciencia-tecnologia-15mai2024.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Chadwick, A., & Vaccari, C. (2019). News sharing on UK social media: Misinformation, disinformation, and correction. Loughborough University. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2134/37720 (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- de Freitas Netto, S. V., Sobral, M. F. F., Ribeiro, A. R. B., & Soares, G. R. d. L. (2020). Concepts and forms of greenwashing: A systematic review. Environmental Sciences Europe, 32(1), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M. A., & Burbano, V. C. (2011). The drivers of greenwashing. California Management Review, 54(1), 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vicario, M., Bessi, A., Zollo, F., Petroni, F., Scala, A., Caldarelli, G., Stanley, H. E., & Quattrociocchi, W. (2016). The spreading of misinformation online. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(3), 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demuru, P. (2020). Conspiracy theories, messianic populism and everyday social media use in contemporary Brazil: A glocal semiotic perspective. Glocalism: Journal of Culture, Politics and Innovation, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doudaki, V., & Carpentier, N. (2023). Behind the narratives of climate change denial and rights of nature: Sustainability and the ideological struggle between anthropocentrism and ecocentrism in two radical facebook groups in Sweden. Journal of Political Ideologies, 30(1), 200–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, M. E. (2023). News to me: Far-right news sharing on social media. Information, Communication & Society, 27(1), 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejaz, W., Mukherjee, M., & Fletcher, R. (2025). Climate change and news audiences report 2024: Analysis of news use and attitudes in eight countries. Oxford Climate Journalism Network. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R. M., Matthes, J., & Pellicano, L. (2009). Nature, sources, and effects of news framing. In K. Wahl-Jorgensen, & T. Hanitzsch (Eds.), The handbook of journalism studies (1st ed., pp. 175–190). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, R., & Bruno, F. (2019). WhatsApp and political instability in Brazil: Targeted messages and political radicalisation. Internet Policy Review, 8(4), 1–23. Available online: https://policyreview.info/articles/analysis/whatsapp-and-political-instability-brazil-targeted-messages-and-political (accessed on 28 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Figenschou, T. U., & Ihlebæk, K. A. (2018). Challenging journalistic authority: Media criticism in far-right alternative media. Journalism Studies, 20(9), 1221–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, A. (2016). What is the story with sustainability? A narrative analysis of diverse and contested understandings. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 7, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garimella, K., & Tyson, G. (2018). WhatsApp doc? A first look at WhatsApp public group data. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 12(1), 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazebrook, T., & Opoku, E. (2018). Defending the defenders: Environmental protectors, climate change and human rights. Ethics and the Environment, 23(2), 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, M. H., Marlon, J. R., Wang, X., van der Linden, S., & Leiserowitz, A. (2020). Oil and gas companies invest in legislators that vote against the environment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(9), 5111–5112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grootendorst, M. (2022). BERTopic: Neural topic modeling with a class-based TF-IDF procedure. arXiv, arXiv:2203.05794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güran, M. S., & Özarslan, H. (2022). Framing theory in the age of social media. Selçuk Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, 48, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberl, H., Wiedenhofer, D., Virág, D., Kalt, G., Plank, B., Brockway, P., Fishman, T., Hausknost, D., Krausmann, F., Leon-Gruchalski, B., Mayer, A., Pichler, M., Schaffartzik, A., Sousa, T., Streeck, J., & Creutzig, F. (2020). A systematic review of the evidence on decoupling of GDP, resource use and GHG emissions, part II: Synthesizing the insights. Environmental Research Letters, 15(6), 065003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, D., Valenzuela, S., Katz, J., & Miranda, J. P. (2019). From belief in conspiracy theories to trust in others: Which factors influence exposure, believing, and sharing fake news. In G. Meiselwitz (Ed.), Social computing and social media. Design, human behavior and analytics. HCII 2019 (Vol. 11578, pp. 166–182). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickel, J., & Kallis, G. (2020). Is green growth possible? New Political Economy, 25(4), 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homar, A. R., & Knežević Cvelbar, L. (2021). The effects of framing on environmental decisions: A systematic literature review. Ecological Economics, 183, 106950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsey, M. J., & Fielding, K. S. (2020). Understanding (and reducing) inaction on climate change. Social Issues and Policy Review, 14(1), 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseini, M., Melo, P., Benevenuto, F., Feldmann, A., & Zannettou, S. (2023, April 30–May 1). On the globalization of the QAnon conspiracy theory through telegram. 15th ACM Web Science Conference 2023 (pp. 75–85), Austin, TX, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, P. N. (2020). Lie machines: How to save democracy from troll armies, deceitful robots, junk news operations, and political operatives. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. (2022). Climate change 2022: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. In H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E. S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, & B. Rama (Eds.), Contribution of working group II to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issberner, L.-R., & Léna, P. (Orgs.). (2016). Brazil in the Anthropocene: Conflicts between predatory development and environmental policies. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasser, G., McSwiney, J., Pertwee, E., & Zannettou, S. (2023). ‘Welcome to #GabFam’: Far-right virtual community on Gab. New Media & Society, 25(7), 1728–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Júnior, M., Melo, P., da Silva, A. P. C., Benevenuto, F., & Almeida, J. (2021). Towards understanding the use of Telegram by political groups in Brazil. In Brazilian symposium on multimedia and the web (pp. 237–244). Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, J., & Puschmann, C. (2017). Alliance of antagonism: Counterpublics and polarization in online climate change communication. Communication and the Public, 2(4), 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermani, H., Makou, A. B., Tafreshi, A., Ghodsi, A. M., Atashzar, A., & Nojoumi, A. (2023). Computational vs. qualitative: Analyzing different approaches in identifying networked frames during the COVID-19 crisis. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 27(4), 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J., Janulewicz, L., & Arcostanzo, F. (2022). Deny, deceive, delay: Documenting and responding to climate disinformation at COP26 and beyond. Institute for Strategic Dialogue. Available online: https://foe.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/COP26-Summative-Report.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- La, V.-P., Nguyen, M.-H., & Vuong, Q.-H. (2024). Climate change denial theories, skeptical arguments, and the role of science communication. SN Social Sciences, 4(10), 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, W. F., Mattioli, G., Levi, S., Roberts, J. T., Capstick, S., Creutzig, F., Minx, J. C., Müller-Hansen, F., Culhane, T., & Steinberger, J. K. (2020). Discourses of climate delay. Global Sustainability, 3, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiserowitz, A., Maibach, E., Rosenthal, S., Kotcher, J., Bergquist, P., Ballew, M., Goldberg, M., Gustafson, A., & Wang, X. (2020). Climate change in the american mind: April 2020. Yale University and George Mason University. Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowsky, S. (2021). Liberty and the pursuit of science denial. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 42, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowsky, S., Cook, J., & Lloyd, E. (2018). The ‘Alice in Wonderland’ mechanics of the rejection of (climate) science: Simulating coherence by conspiracism. Synthese, 195(1), 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes de Oliveira, D., & Lewenstein, B. V. (2024). Supporting activism in Latin America: The role of science communication, science journalism, and NGOs in socio-environmental conflicts. Journalism Studies, 25(5), 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lück, J., Wessler, H., Wozniak, A., & Lycarião, D. (2018). Counterbalancing global media frames with nationally colored narratives: A comparative study of news narratives and news framing in the climate change coverage of five countries. Journalism, 19(12), 1635–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malzer, C., & Baum, M. (2020, September 14–16). A hybrid approach to hierarchical density-based cluster selection. 2020 IEEE International Conference on Multisensor Fusion and Integration for Intelligent Systems (MFI) (pp. 223–228), Karlsruhe, Germany. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MapBiomas. (2024). Relatório Anual do Desmatamento (RAD) no Brasil 2023. Mapbiomas. Available online: https://alerta.mapbiomas.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/17/2024/10/RAD2023_COMPLETO_15-10-24_PORTUGUES.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- McInnes, L., Healy, J., Saul, N., & Großberger, L. (2018). UMAP: Uniform manifold approximation and projection. Journal of Open Source Software, 3(29), 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, P., Salles, D. G., Magalhães, T., Melo, B., & Santini, R. M. (2024). Greenwashing e desinformação: A publicidade tóxica do agronegócio brasileiro nas redes. Comunicação e Sociedade, 45, e024008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medeiros, P., Salles, D. G., Santos, M. L., & Oliveira, R. M. S. d. (2023, July 3–7). Desinformação socioambiental como ferramenta de propaganda: Uma análise multiplataforma sobre a crise humanitária Yanomami. Anais do 32° Encontro Anual da Compós, São Paulo, Brazil. Available online: https://proceedings.science/compos/compos-2023/trabalhos/desinformacao-socioambiental-como-ferramenta-de-propaganda-uma-analise-multiplat?lang=pt-br (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Mendonça, R. F., & Simões, P. G. (2012). Enquadramento: Diferentes operacionalizações analíticas de um conceito. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais, 27(79), 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, J. C. (2020). Negacionismo climático no Brasil. Coletiva, Dossiê 27. Crise Climática. [Google Scholar]

- Morgia, M. L., Mei, A., Mongardini, A. M., & Wu, J. (2021). Uncovering the dark side of telegram: Fakes, clones, scams, and conspiracy movements. arXiv, arXiv:2111.13530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, S., & Stocking, G. (2023). Key facts about Gettr. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/02/01/key-facts-about-gettr/ (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Ogunbode, C. A., Doran, R., Ayanian, A. H., Park, J., Utsugi, A., van den Broek, K. L., Ghorayeb, J., Aquino, S. D., Lins, S., Aruta, J. J. B. R., Reyes, M. E. S., Zick, A., & Clayton, S. (2024). Climate justice beliefs related to climate action and policy support around the world. Nature Climate Change, 14, 1144–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreskes, N., & Conway, E. M. (2010). Merchants of doubt: How a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming (1st U.S. ed.). Bloomsbury Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa, J. V. S., Woolley, S. C., Straubhaar, J., Riedl, M. J., Joseff, K., & Gursky, J. (2023). How disinformation on WhatsApp went from campaign weapon to governmental propaganda in Brazil. Social Media + Society, 9(1), 20563051231160632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PAHO. (2024). Flooding in Brazil—2024. PAHO—Pan American Health Organization. Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/health-emergencies/flooding-brazil-2024 (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Patterson, J., Wyborn, C., Westman, L., Brisbois, M. C., Milkoreit, M., & Jayaram, D. (2021). The political effects of emergency frames in sustainability. Nature Sustainability, 4, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajão, R., Manzolli, B., Soares-Filho, B., & Galéry, R. (2022). Crise dos fertilizantes no Brasil: Da tragédia anunciada às falsas soluções. UFMG. Available online: https://portal.sbpcnet.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/crise_fertilizantes.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Regattieri, L. (2023). A propaganda desinformativa no projeto de destruição nacional bolsonarista: A desinformação como estratégia de governo na agenda socioambiental durante a presidência de Jair Bolsonaro (PL). Revista Eco-Pós, 26(1), 105–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resende, G., Melo, P., Sousa, H., Messias, J., Vasconcelos, M., Almeida, J., & Benevenuto, F. (2019). (Mis)Information dissemination in WhatsApp: Gathering, analyzing and countermeasures. In The world wide web conference (WWW’19) (pp. 818–828). Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R. (2020). Deplatforming: Following extreme Internet celebrities to Telegram and alternative social media. European Journal of Communication, 35(3), 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossini, P., Stromer-Galley, J., Baptista, E. A., & Veiga de Oliveira, V. (2021). Dysfunctional information sharing on WhatsApp and Facebook: The role of political talk, cross-cutting exposure and social corrections. New Media and Society, 23(8), 2430–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothberg, D. (2010). O conceito de enquadramento e sua contribuição à crítica de mídia. In R. Christofoletti (Ed.), Vitrine e vidraça: Crítica de mídia e qualidade no jornalismo (pp. 53–68). Labcom Books. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, S., Schimperna, F., Lombardi, R., & Ruggiero, P. (2022). Sustainability performance and social media: An explorative analysis. Meditari Accountancy Research, 30(4), 1118–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salles, D., de Medeiros, P. M., Santini, R. M., & Barros, C. E. (2023). The far-right smokescreen: Environmental conspiracy and culture wars on Brazilian YouTube. Social Media + Society, 9(3), 20563051231196876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salles, D., Muniz de Medeiros, P., Martins, B., Regattieri, L., & Santini, R. M. (2024). The role of social bots in the Brazilian environmental debate: An analysis of the 2020 Amazon Forest fires in Twitter. The International Review of Information Ethics, 33(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, R. M., Salles, D., & Barros, C. E. (2022). We love to hate George Soros: A cross-platform analysis of the Globalism conspiracy theory campaign in Brazil. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 28(4), 983–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, R. M., Tucci, G., Salles, D., & Almeida, A. R. D. (2021). Do you believe in fake after all? WhatsApp disinformation campaign during the Brazilian 2018 presidential elections. In Politics of disinformation: The influence of fake news on the public sphere. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, M., Melo, B., Magalhães, T., Dias, J., & Salles, D. (2024, November 6–8). (RE)PRODUÇÃO LOCAL DE DESINFORMAÇÃO: A cobertura da CPI das ONGs na Amazônia Legal. Anais do 22º Encontro Nacional de Pesquisadores em Jornalismo (Vol. 22), Belém, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Schulze, H., Hohner, J., Greipl, S., Girgnhuber, M., Desta, I., & Rieger, D. (2022). Far-right conspiracy groups on fringe platforms: A longitudinal analysis of radicalization dynamics on Telegram. Convergence, 28(4), 1103–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D., & Ridart, A. (2023). A agenda ambiental entre os desafios de governabilidade no governo Lula. Nexo. Available online: https://pp.nexojornal.com.br/ponto-de-vista/2023/06/13/a-agenda-ambiental-entre-os-desafios-de-governabilidade-no-governo-lula/ (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Silva, E. C. d. M. (2024). Climate change denial and anti-science communities on brazilian Telegram: Climate disinformation as a gateway to broader conspiracy networks. arXiv, arXiv:2408.15311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R., Chen, K., Winner, D., Friedhoff, S., & Wardle, C. (2023). A systematic review of COVID-19 misinformation interventions: Lessons learned. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 42(12), 1738–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, O. (2023). O que você precisa saber para entender a crise na Terra Indígena Yanomami. Instituto Socioambiental—ISA. Available online: https://www.socioambiental.org/noticias-socioambientais/o-que-voce-precisa-saber-para-entender-crise-na-terra-indigena-yanomami (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Spampatti, T., Hahnel, U. J. J., Trutnevyte, E., & Brosch, T. (2024). Psychological inoculation strategies to fight climate disinformation across 12 countries. Nature Human Behaviour, 8(2), 380–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spektor, M., Fasolin, G. N., & Camargo, J. (2023). Climate change beliefs and their correlates in Latin America. Nature Communications, 14(1), 7241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statista. (2024). WhatsApp in Brazil—Statistics & facts. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/7731/whatsapp-in-brazil/ (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Telegram. (n.d.-a). Canais do telegram. Telegram. Available online: https://telegram.org/tour/channels/pt-br (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Telegram. (n.d.-b). Grupos do telegram. Telegram. Available online: https://telegram.org/tour/groups/pt-br (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Törnberg, A., & Nissen, A. (2023). Mobilizing against Islam on social media: Hyperlink networking among European far-right extra-parliamentary Facebook groups. Information, Communication & Society, 26(15), 2904–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treen, K. M. d., Williams, H. T. P., & O’Neill, S. J. (2020). Online misinformation about climate change. WIREs Climate Change, 11(5), e665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2024). Press and planet in danger: Safety of environmental journalists; trends, challenges, and recommendations. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000389501 (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- UNESCO & MECCE. (2024). Education and climate change: Learning to act for people and planet. UNESCO. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN News. (2024, November 19). New UN initiative aims to counter climate disinformation. UN News. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2024/11/1157191 (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Urbano, K., Oliveira, T., Evangelista, S., & Massarani, L. (2024). Mapeando a desinformação sobre o meio ambiente na América Latina e no Caribe: Uma análise bibliométrica de um campo incipiente de pesquisa. Journal of Science Communication—América Latina, 7(01), A02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urman, A., & Katz, S. (2020). What they do in the shadows: Examining the far-right networks on Telegram. Information, Communication & Society, 25(7), 904–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicenová, R., & Mišík, M. (2025). Far-right greenwashing: The twisting of sustainability. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, H. T., Blomberg, M., Seo, H., Liu, Y., Shayesteh, F., & Do, H. V. (2020). Social media and environmental activism: Framing climate change on Facebook by global NGOs. Science Communication, 43(1), 91–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., Wei, F., Dong, L., Bao, H., Yang, N., & Zhou, M. (2020). MiniLM: Deep self-attention distillation for task-agnostic compression of pre-trained transformers. arXiv, arXiv:2002.10957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendratama, E., & Yusuf, I. (2023). COVID-19 falsehoods on WhatsApp: Challenges and opportunities in Indonesia. In C. Soon (Ed.), Mobile communication and online falsehoods in asia. Mobile communication in Asia: Local insights, global implications. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WWA. (2024a, January 24). Climate change, not El Niño, main driver of exceptional drought in highly vulnerable Amazon River Basin. World Weather Attribution—WWA. Available online: https://www.worldweatherattribution.org/climate-change-not-el-nino-main-driver-of-exceptional-drought-in-highly-vulnerable-amazon-river-basin/ (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- WWA. (2024b, August 8). Hot, dry and windy conditions that drove devastating Pantanal wildfires 40% more intense due to climate change. World Weather Attribution—WWA. Available online: https://www.worldweatherattribution.org/hot-dry-and-windy-conditions-that-drove-devastating-pantanal-wildfires-40-more-intense-due-to-climate-change/ (accessed on 28 May 2025).

| Topic | Example of Message Shared on WhatsApp (Portuguese) | Example of Message Shared on WhatsApp (English Translation) |

|---|---|---|

| Attacks on the Lula Government environmental policy | Manaus tem o pior índice de Queimadas para o mês de outubro dos últimos 25 anos e novamente fica encoberta por fumaça EFEITO LULA, DEVASTANDO A AMAZÔNIA EM QUEIMADAS E A MÍDIA E ONGs COMPRADA RECEBENDO RIOS DE DINHEIRO FICAM CALADOS | Manaus has the worst rate of fires for the month of October in the last 25 years and is once again covered in smoke. THE LULA EFFECT, DEVASTATING THE AMAZON BY FIRE AND THE MEDIA AND NGOs PAID OFF, RECEIVING RIVERS OF MONEY, STAY SILENT |

| Attacks on MST | Mulher, ex-assentada do MST enfrenta ameaças e fake news após denunciar MST na CPI #COMPARTILHE | Woman, former MST settler faces threats and fake news after reporting MST to the Parliamentary Inquiry #SHARE |

| In defense of agribusiness | “O Brasil não é o país do carnaval; nem é o país do futebol. O Brasil é o país do AGRO, que alimenta boa parte do mundo, exportando para mais de 170 países” O AGRO MERECE RESPEITO! | “Brazil is not the land of carnival; nor the land of soccer. Brazil is the land of AGRIBUSINESS, which feeds a large part of the world, exporting to more than 170 countries” AGRIBUSINESS DESERVES RESPECT! |

| Conspiracy theories | Melhor virar vegetariano kkkkk Embrapa anuncia filé de frango de laboratório para final desse ano * AGENDA 2030  Comida sintética, o futuro da humanidade, bem vindo a agenda sustentável, continue confiando nos governos OMS ONU e no Tio Bill pois eles só querem o seu bem! | Better to become a vegetarian lol * Embrapa announces lab-grown chicken fillet for the end of this year 2030 AGENDA  Synthetic food, the future of humanity, welcome to the sustainable agenda, keep trusting the governments WHO UN and Uncle Bill because they only want the best for you! |

| Ukraine War and fertilizers | Lá vem a guerra lascando os Fertilizantes… | Here comes the war, destroying the Fertilizers… |

| Attacks on NGOs | É para isso que servem as ongs instaladas na Amazônia, escravizar os índios fazer fortuna as custas de uma falsa política de preservação do meio ambiente, canalhas… | This is what the NGOs installed in the Amazon are for, to enslave the indigenous people and make a fortune at the expense of a false environmental preservation policy, scoundrels… |

| Bolsonaro helped the environment | SE ALGUÉM PERGUNTAR O QUE FOI QUE O PR.BOLSONARO FEZ DE BOM PARA O BRASIL, MOSTRE ESSA LISTA ABAIXO COM ALGUMAS COISAS QUE ELE FEZ. 1. Criou o PIX 2. Deu 33% de aumento aos professores. (…) 7. Obteve recordes na exportação brasileira. 8. Obteve superavit na balança comercial do Brasil. (…) 18. Transposição do Rio São Francisco, parada há décadas—Água para o Nordeste. | IF SOMEONE ASKS WHAT GOOD THINGS PR. BOLSONARO DID FOR BRAZIL, SHOW THEM THIS LIST BELOW WITH SOME THINGS HE DID. 1. Created PIX 2. Gave 33% raises to teachers. (…) 7. Obtained records in Brazilian exports. 8. Obtained a surplus in Brazil’s trade balance. (…) 18. Transposition of the São Francisco River, stopped for decades—Water for the Northeast. |

| Forest fire |  Chile declara estado de emergência devido a grandes incêndios florestais, mais de 1000 casas destruídas, 10 mortes relatadas. Chile declara estado de emergência devido a grandes incêndios florestais, mais de 1000 casas destruídas, 10 mortes relatadas. |  Chile declares state of emergency due to massive wildfires, over 1000 homes destroyed, 10 deaths reported. Chile declares state of emergency due to massive wildfires, over 1000 homes destroyed, 10 deaths reported. |

| Topic | Example of Message Shared on Telegram (Portuguese) | Example of Message Shared on Telegram (English Translation) |

|---|---|---|

| Attacks on the Lula Government environmental policy | As queimadas na Amazônia continuam sem solução, mesmo após vários meses do governo Lula com Marina Silva a frente do Ministério do Meio Ambiente. Nesta quinta-feira (06), a capital do Amazonas, Manaus, amanheceu com o ar tomado por fumaça, devido às queimadas que estão ocorrendo na região. | The fires in the Amazon remain unresolved, even after several months of the Lula government with Marina Silva at the head of the Ministry of the Environment. This Thursday (06), the capital of Amazonas, Manaus, woke up to the air filled with smoke, due to the fires that are occurring in the region. |

| Attacks on MST | MINISTRO DO STF É ‘FLAGRADO’ DESCONTRAIDAMENTE EM EVENTO DO MST Bem à vontade. | “SUPREME COURT MINISTER IS ‘CAUGHT’ AT MST EVENT, LOOKING AT EASE. Very comfortable. |

| In defense of agribusiness | O agronegócio brasileiro é um dos setores mais importantes da economia do país, pois trata se do setor primário, representando cerca de 1/3 do PIB nacional. O Brasil é um dos maiores produtores e exportadores de grãos do mundo. Além disso, agro é responsável por gerar milhões de empregos em todo o país, tanto no campo como na agro-indústria e comércio. O agro brasileiro merece respeito, e estou na Câmara dos Deputados para defender essa classe que alimenta o mundo | Brazilian agribusiness is one of the most important sectors of the country’s economy, as it is the primary sector, representing about 1/3 of the national GDP. Brazil is one of the largest producers and exporters of grain in the world. In addition, agribusiness is responsible for generating millions of jobs throughout the country, both in the countryside and in agro-industry and commerce. Brazilian agribusiness deserves respect, and I am in the Chamber of Deputies to defend this sector that feeds the world. |

| Conspiracy theories | Cientistas nos Estados Unidos estão recebendo financiamento maciço para testar novos sistemas de vacinas de mRNA em roedores, gado e produtos agrícolas | Scientists in the United States are receiving massive funding to test new mRNA vaccine systems in rodents, livestock and agricultural products |

| Ukraine War and fertilizers | A Única coisa que o Bolsonaro buscava com o Putin era fertilizantes, adotando o pragmatismo. O Putin é muito mais próximo do LULA, e inclusive da respaldo pra invasão da Ucrania por meio do Itamaraty e do Celso Amorim. O Lula ja criticou diversas vezes a OTAN e ja culpou a otan pela guerra da Ucrânia. Se não for o bastante, ele ainda é a favor da mesma ideia de mundo “multipolar” que a Rússia prega junto da China e da quebra da hegemonia do Dólar. Até mesmo o atual cotado Pro STF, Flavio Dino, que deveria ser seu ídolo, estava a favor de tirar o Brasil da TPI pra receber seu Putin de braços abertos! | The only thing Bolsonaro was after with Putin was fertilizer, being pragmatic. Putin is much closer to LULA, and even supports the invasion of Ukraine through Itamaraty and Celso Amorim. Lula has criticized NATO several times and has already blamed NATO for the war in Ukraine. If that is not enough, he is also in favor of the same idea of a “multipolar” world that Russia preaches together with China and overturning the dominance of the Dollar. Even the current candidate for the Supreme Court, Flavio Dino, who should be his idol, was in favor of removing Brazil from the ICC to welcome Putin with open arms! |

| Attacks on NGOs | Os americanos não são burros, eles já exploram a Amazônia sem precisar de intervenção militar na região. Fazem isso através de políticos vendidos que colocam no congresso para proteger suas ONGs. O fundo Amazônia por exemplo… não vai um centavo pra beneficiar alguma prefeitura ou governo local… todo dinheiro que eles mandam pra esse fundo só pode ir para suas próprias ONGs na Amazônia, que servem como mineradoras clandestinas na região. | The Americans are not stupid. They already exploit the Amazon without needing military intervention in the region. They do this through corrupt politicians who they put in Congress to protect their NGOs. The Amazon Fund, for example… not a single cent goes to benefit any city hall or local government… all the money they send to this fund can only go to their own NGOs in the Amazon, which serve as clandestine mining companies in the region. |

| Bolsonaro helped the environment | “INDÍGENAS EM ESTADO DE DESNUTRIÇÃO EM RORAIMA SÃO VENEZUELANOS E FRUTO DO COMUNISMO”. ENTENDA; Entre os milhares de venezuelanos que fogem da ditadura bolivariana estão estes indígenas yanomamis, que necessitam de todo acolhimento e cuidado. | “INDIGENOUS PEOPLE IN A STATE OF MALNUTRITION IN RORAIMA ARE VENEZUELANS AND THE RESULT OF COMMUNISM”. UNDERSTAND; Among the thousands of Venezuelans fleeing the Bolivarian dictatorship are these Yanomami indigenous people, who need care and support |

| Forest fire |  A AMAZÔNIA ESTÁ QUEIMANDO: Com quase 7000 incêndios florestais registrados até 29 de setembro, o estado do Amazonas teve seu pior mês do ano em termos de incêndios florestais. É o segundo pior setembro já registrado desde o início da série histórica em 1998, sendo que em apenas 2022 teve maior número de incêndios florestais, com 8600. A AMAZÔNIA ESTÁ QUEIMANDO: Com quase 7000 incêndios florestais registrados até 29 de setembro, o estado do Amazonas teve seu pior mês do ano em termos de incêndios florestais. É o segundo pior setembro já registrado desde o início da série histórica em 1998, sendo que em apenas 2022 teve maior número de incêndios florestais, com 8600. |  THE AMAZON IS BURNING: With almost 7000 forest fires registered up to September 29, the state of Amazonas had its worst month of the year in terms of forest fires. It is the second worst September on record since records began in 1998, and only 2022 saw a higher number of forest fires, with 8600. THE AMAZON IS BURNING: With almost 7000 forest fires registered up to September 29, the state of Amazonas had its worst month of the year in terms of forest fires. It is the second worst September on record since records began in 1998, and only 2022 saw a higher number of forest fires, with 8600. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santini, R.M.; Salles, D.G.; Santos, M.L.; Leopoldo Belin, L.; Ciodaro, T. Anti-Sustainability Narratives in Chat Apps: What Shapes the Brazilian Far-Right Discussion About Socio-Environmental Issues on WhatsApp and Telegram. Journal. Media 2025, 6, 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6020085

Santini RM, Salles DG, Santos ML, Leopoldo Belin L, Ciodaro T. Anti-Sustainability Narratives in Chat Apps: What Shapes the Brazilian Far-Right Discussion About Socio-Environmental Issues on WhatsApp and Telegram. Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(2):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6020085

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantini, Rose Marie, Débora Gomes Salles, Marina Loureiro Santos, Luciane Leopoldo Belin, and Thiago Ciodaro. 2025. "Anti-Sustainability Narratives in Chat Apps: What Shapes the Brazilian Far-Right Discussion About Socio-Environmental Issues on WhatsApp and Telegram" Journalism and Media 6, no. 2: 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6020085

APA StyleSantini, R. M., Salles, D. G., Santos, M. L., Leopoldo Belin, L., & Ciodaro, T. (2025). Anti-Sustainability Narratives in Chat Apps: What Shapes the Brazilian Far-Right Discussion About Socio-Environmental Issues on WhatsApp and Telegram. Journalism and Media, 6(2), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6020085