Mobile Media as an “Essential” Tool for Collective Action: Explaining Intentions for Disruptive Political Behavior in U.S. Politics

Abstract

:1. Mobile Media as an “Essential” Tool for Collective Action: Explaining Intentions for Disruptive Political Behavior in U.S. Politics

1.1. Collective Action, Media, and the Far-Right

1.2. Mobile Communication and Collective Action

since the 1990s, the sudden emergence of SMS as a ubiquitous form of messaging, and the increasing interconnection between mobile phones and the Internet have made it possible for people to coordinate and organize political collective action with people they were not able to organize before, in places they weren’t able to organize before, and at a speed they weren’t able to muster before.(p. 226)

1.3. Folk Theories and the Essence of Mobile Media

1.4. The Moderating Role of Micro-Coordination

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

3. Results

3.1. Mobile Phone Essence as Collective Action

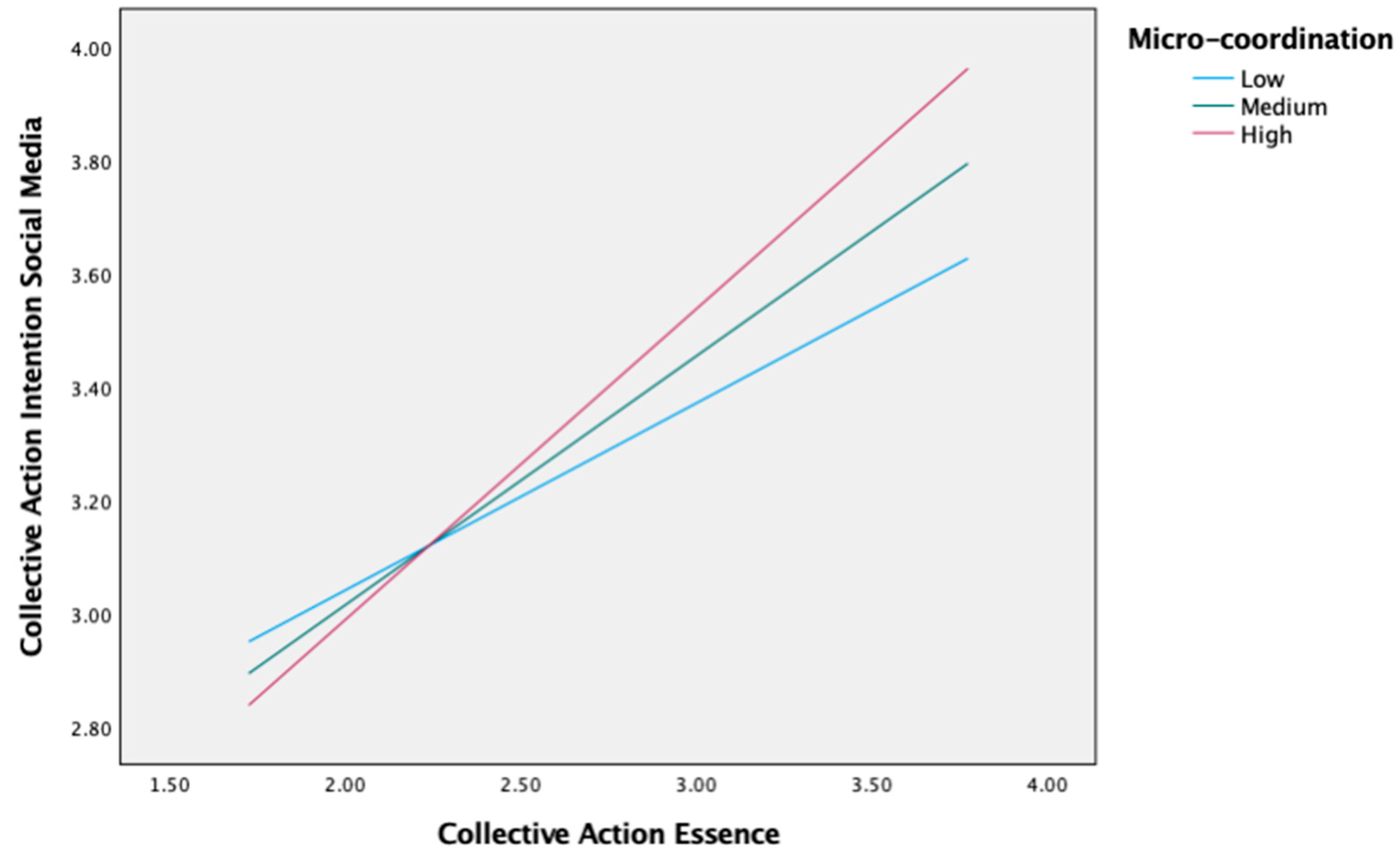

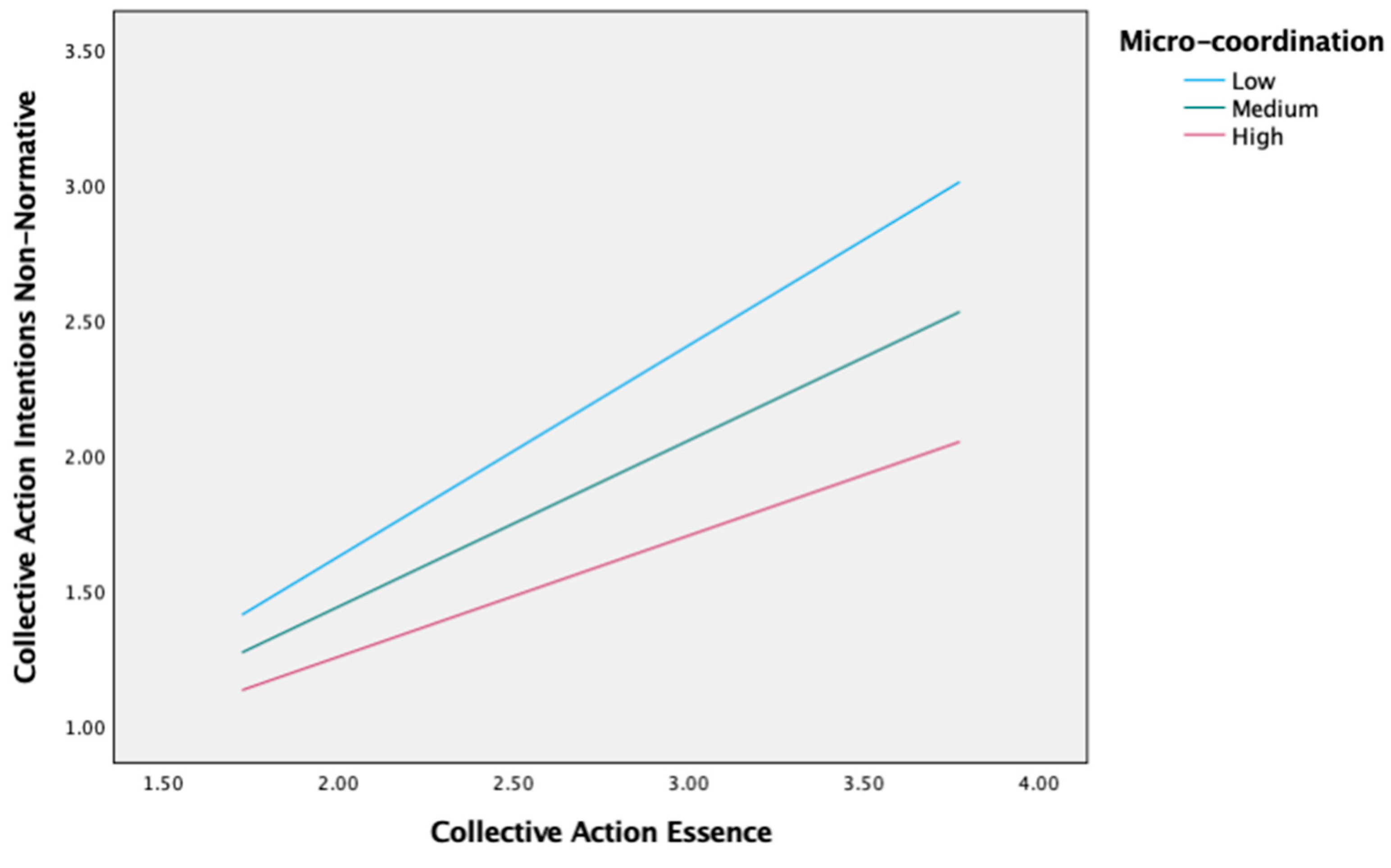

3.2. Tests of Moderation

4. Discussion

5. Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bagalawis, Jennifer E. 2001. How IT Helped Topple a President. Available online: http://www.itworld.com/CW_1-31-01_it (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Bailard, Catie S. 2015. Ethnic conflict goes mobile: Mobile technology’s effect on the opportunities and motivations for violent collective action. Journal of Peace Research 52: 323–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, Ted, Manu Raju, and Peter Nickeas. 2021. Capitol Secured, 4 Dead after Rioters Stormed the Halls of Congress to Block Biden’s Win. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2021/01/06/politics/us-capitol-lockdown/index.html (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Becker, Julia C., Nicole Tausch, Russell Spears, and Oliver Christ. 2011. Committed dis(s)idents: Participation in radical collective action fosters disidentification with the broader in-group but enhances political identification. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 37: 1104–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertel, Troels. F. 2013. “Its like I trust it so much that I don’t really check where it is I’m going before I leave”: Informational uses of smartphones among danish youth. Mobile Media & Communication 1: 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimber, Bruce. 2017. Three prompts for collective action in the context of digital media. Political Communication 34: 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Scott. W. 2013. Mobile media and communication: A new field or just a new journal? Mobile Media & Communication 1: 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Scott W., and Nojin Kwak. 2010. Mobile communication and civic life: Linking patterns of use to civic and political engagement. Journal of Communication 60: 536–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Scott W., and Nojin Kwak. 2011. Political involvement in “mobilized” society: The interactive relationships among mobile communication, network characteristics, and political participation. Journal of Communication 61: 1005–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, Manuel, Mireia Fernandez-Ardevol, Jack Linchuan Qiu, and Araba Sey. 2007. Mobile Communication and Society: A Global Perspective. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Michael. 2014. Social identity gratifications of social network sites and their impact on collective action participation. Asian Journal of Social Psychology 17: 229–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVito, Michael A., Jeremy Birnholtz, Jeffery T. Hancock, Megan French, and Sunny Liu. 2018. How people form folk theories of social media feeds and what it means for how we study self-presentation. Paper presented at the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, April 21–26; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Eslami, Motahhare, Karrie Karahalios, Christian Sandvig, Kristen Vaccaro, Aimee Rickman, Kevin Hamilton, and Alex Kirlik. 2016. First I “like” it, then I hide it: Folk Theories of Social Feeds. Paper presented at the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, May 7–12; pp. 2371–82. [Google Scholar]

- Forscher, Patrick S., and Nour S. Kteily. 2020. A Psychological Profile of the Alt-Right. Perspectives on Psychological Science 15: 90–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, Sheera. 2021. The Storming of Capitol Hill Was Organized on Social Media. Available online: https://www.times.com/2021/01/06/us/politics/protesters-storm-capitol-hill-building.html (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Fulford, B. 2003. Korea’s weird wired world: Strange things happen when an entire country is hooked on high-speed Internet. Forbes 7: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Glasford, Demis E., and Justine Calcagno. 2012. The conflict of harmony: Intergroup contact, commonality and political solidarity between minority groups. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 48: 323–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, Ian, and Muniba Saleem. 2021. Rise UP!: A content analytic study of how collective action is discussed within White nationalist videos on YouTube. New Media & Society. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F., and Kris J. Preacher. 2014. Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology 67: 451–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiaeshutter-Rice, Dan, and Ian Hawkins. 2022. The language of extremism on social media: An examination of posts, comments, and themes on reddit. Frontiers in Political Science 4: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, Lee. 2013. Mobile social media: Future challenges and opportunities. Mobile Media & Communication 1: 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys, Lee, Veronika Karnowski, and von Thilo Von Pape. 2018. Smartphones as metamedia: A framework for identifying the niches structuring smartphone use. International Journal of Communication 12: 2793–809. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Hyeon-Suk. 2014. Re-conceptualization of the Curriculum Design and Pedagogy through Bruner’s Idea of Narrative1. International Information Institute (Tokyo). Information 17: 5269. [Google Scholar]

- Kanthawala, Shaheen, Eunsin Joo, Anastasia Kononova, Wei Peng, and Shelia Cotten. 2019. Folk theorizing the quality and credibility of health apps. Mobile Media & Communication 7: 175–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, Caroline, and Sara Breinlinger. 1995. Identity and injustice: Exploring women’s participation in collective action. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 5: 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keneally, Meghan. 2018. What to Know about the Violent Charlottesville Protests and Anniversary Rallies. Available online: https://abcnews.go.com/US/happen-charlottesville-protest-anniversary-weekend/story?id=57107500 (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Law, Pui-Lam. 2014. Political communication, the internet, and mobile media: The case of Passion Times in Hong Kong. In The Routledge Companion to Mobile Media. Edited by Gerald Goggin and Larissa Hjorth. New York: Routledge, pp. 419–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Claire Seungeun, Juan Merizalde, John D. Colautti, Jisun An, and Haewoon Kwak. 2022. Storm the Capitol: Linking Offline Political Speech and Online Twitter Extra-Representational Participation on QAnon and the January 6 Insurrection. Frontiers in Sociology 7: 876070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licoppe, Christian. 2004. ‘Connected’ Presence: The Emergence of a New Repertoire for Managing Social Relationships in a Changing Communication Technoscape. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 22: 135–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Rich. 1997. One can talk about common manners!: The use of mobile telephones in inappropriate situations. In Communications on the Move: The Experience of Mobile Telephony in the 1990s. Edited by L. Haddon. Kjeller: Norway, pp. 60–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, Rich. 2012. Taken for Grantedness: The Embedding of Mobile Communication into Society. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, Rich, and Chih-Hui Lai. 2016. Microcoordination 2.0: Social coordination in the age of smartphones and messaging apps. Journal of Communication 66: 834–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Rich, and Birgitte Yttri. 2002. 10 Hyper-coordination via mobile phones in Norway. In Perpetual Contact. Mobile Communication, Private Talk, Public Performance. Edited by James E. Katz and Mark Aakhus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 139–69. [Google Scholar]

- Litman, Leib, Jonathan Robinson, and Tzvi Abberbock. 2017. TurkPrime.com: A versatile crowdsourcing data acquisition platform for the behavioral sciences. Behavior Research Methods 49: 433–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Jun. 2016. Mobile phones, social ties and collective action mobilization in China. Acta Sociologica 60: 213–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskalenko, Sophia, and Clark McCauley. 2009. Measuring political mobilization: The distinction between activism and radicalism. Terrorism and Political Violence 21: 239–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundt, Marcia, Karen Ross, and Charla M. Burnett. 2018. Scaling Social Movements Through Social Media: The Case of Black Lives Matter. Social Media + Society 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumayer, Christina. 2020. Political protest and mobile communication. In The Oxford Handbook of Mobile Communication and Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 243–56. [Google Scholar]

- Neumayer, Christina, and Gitte Stald. 2014. The mobile phone in street protest: Texting, tweeting, tracking, and tracing. Mobile Media & Communication 2: 117–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paragas, Fernando. 2003. Dramatextism Mobile Telephony and People Power in the Philippines. In Mobile Democracy: Essays on Society, Self and Politics. Edited by Kristof Nyiri. Vienna: Passagen Verlag, pp. 259–283. [Google Scholar]

- Pertierra, Raul, Eduardo F. Ugarte, Alicia Pingol, Joel Hernandez, and Nikos Lexis Dacanay. 2002. Txt-ing Selves: Cellphones and Philippine Modernity. Manila: De La Salle University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pierskalla, Jan, and Florian Hollenbach. 2013. Technology and Collective Action: The Effect of Cell Phone Coverage on Political Violence in Africa. American Political Science Review 107: 207–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, Avinash, Dipanwita Guhathakurta, Jivtesh Jain, Mallika Subramanian, Manvith Reddy, Shradha Sehgal, Tanvi Karandikar, Amogh Gulati, Udit Arora, Ratn Shah, and et al. 2021. Capitol (Pat) riots: A comparative study of Twitter and Parler. arXiv arXiv:2101.06914. [Google Scholar]

- Rader, Emilee, and Janine Slaker. 2017. The importance of visibility for folk theories of sensor data. Paper presented at Thirteenth Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security (SOUPS 2017), Santa Clara, CA, USA, July 12–14; pp. 257–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, Rashawn, Melissa Brown, and Wendy Laybourn. 2017. The evolution of# BlackLivesMatter on Twitter: Social movements, big data, and race. Ethnic and Racial Studies 40: 1795–96. [Google Scholar]

- Rhee, Lisa, Joseph B. Bayer, David S. Lee, and Ozan Kuru. 2021. Social by definition: How users define social platforms and why it matters. Telematics and Informatics 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rheingold, Howard. 2002. Smart Mobs: The Next Social Revolution. Cambridge: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero, Thomas E. 2000. Uses and gratifications theory in the 21st century. Mass Communication and Society 3: 3–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toff, Benjamin, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2018. “I just google it”: Folk theories of distributed discovery. Journal of Communication 68: 636–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufekci, Zeynep, and Christopher Wilson. 2012. Social media and the decision to participate in political protest: Observations from tahrir square. Journal of Communication 62: 363–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Swol, Lyn, Sangwon Lee, and Rachel Hutchins. 2022. The banality of extremism: The role of group dynamics and communication of norms in polarization on January 6. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice 26: 239–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanden Abeele, Mariek MP. 2016. Mobile lifestyles: Conceptualizing heterogeneity in mobile youth culture. New Media & Society 18: 908–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Alt-Right Identity | − | |||||

| 2. Essence CA | 0.12 * | − | ||||

| 3. Microcoordination | −0.01 | 0.12 * | − | |||

| 4. CA offline | 0.12 * | 0.52 ** | −0.03 | − | ||

| 5. CA social media | 0.18 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.01 | 0.79 ** | − | |

| 6. CA non-normative | 0.21 ** | 0.55 ** | −0.23 ** | 0.56 ** | 0.42 ** | − |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hawkins, I.; Campbell, S.W.; Gelderman, A. Mobile Media as an “Essential” Tool for Collective Action: Explaining Intentions for Disruptive Political Behavior in U.S. Politics. Journal. Media 2023, 4, 258-271. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4010018

Hawkins I, Campbell SW, Gelderman A. Mobile Media as an “Essential” Tool for Collective Action: Explaining Intentions for Disruptive Political Behavior in U.S. Politics. Journalism and Media. 2023; 4(1):258-271. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleHawkins, Ian, Scott W. Campbell, and Andrew Gelderman. 2023. "Mobile Media as an “Essential” Tool for Collective Action: Explaining Intentions for Disruptive Political Behavior in U.S. Politics" Journalism and Media 4, no. 1: 258-271. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4010018

APA StyleHawkins, I., Campbell, S. W., & Gelderman, A. (2023). Mobile Media as an “Essential” Tool for Collective Action: Explaining Intentions for Disruptive Political Behavior in U.S. Politics. Journalism and Media, 4(1), 258-271. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4010018