Abstract

The article focuses on mobile democracy in connection to the conditional foundations for young Danes’ democratic agency in a digital society. It investigates questions of democratic transformation through a conceptual and empirical triangulation of mobile democracy as a framework for analyzing these conditions. Conceptually, the article draws on research on youth and mobile technologies and on theories of mobility, deliberative democracy, and democratic conversation. Empirically, the article draws on 16 in-depth interviews with 16–24-year-old Danes conducted in 2021. This dataset is supported by findings from a representative survey (2017) and publicly available statistics and surveys. The article analyses three intersecting conditions that frame the concept of mobile democracy through an analysis of young citizens’ democratic participation: 1. Mobile technologies—democratic mobility occurs across the availability of technological mobile platforms and online services. The ‘always on’ status is defining for young citizens’ democratic agency. 2. Mobile information and social media—fragmented publics are increasingly missing societal reference points and ideological coherence, and young people are challenged in their attempt to establish coherent meaningfulness from the fluctuating information stream. 3. Mobile engagement and participation—information mobility affects perceptions of what information, citizenship and democracy are, and how this translates into actualizations of democratic participation.

1. Introduction

The concept of mobile democracy usually refers to the social impact and meaning of mobile, technological devices concerning democratic challenges and opportunities (i.e., Fortunati 2003; Hermanns 2008; Stald 2007; Wei 2020). Recent research has addressed the particular connections between young citizens’ extensive access to and use of mobile devices for accessing new forms of news and information (Duffy et al. 2020; Ohme et al. 2022; Van Damme et al. 2020) and the transformations of news production and use in the context of mobility of media, user access, and perceptions of what news is (Bakker and de Vreese 2011; Kalsnes and Larsson 2018; de Zúñiga et al. 2017). While this article includes these perspectives on mobility transformations, it also expands the actual and metaphorical meaning of mobile democracy in connection to understanding the changing conditional foundations for young citizens’ experience with democratic agency in a digital society. The aim of the article is to address and discuss how we can translate conceptualizations of transformations of fundamental democratic systems and normative perceptions of democracy into practice-related understandings of democratic dynamics that can explain present and support future democratic innovations. A growing body of research literature on new perspectives regarding mobile media, mobile content, news and democratic agency provides important evidence of diverse aspects of young citizens’ encounters with news in a mobility context and of the consequent impact on democratic participation. How these aspects’ intertwined contexts are dynamically transformed is less obvious. This article bridges this knowledge gap by providing a theoretical- and experience-based argument seen from a specific perspective within an old, well-established democratic system. It does so by approaching the core problem of democratic transformation from a combined conceptual and empirical triangulation of mobile democracy as a reference frame and as a consequence of core conditions for actualization of democratic citizenship for young Danes. This is outlined in the research question that guides the analysis and discussion: Which core mobility aspects of information access and experience are fundamentally transforming young citizens’ democratic understanding and participation, and how does this influence the metaphorical mobility of democracy? The research behind the article investigates questions about mobile democracy in a national context. This is relevant because Denmark is an old, generally well-functioning, representative democracy and because trust in democratic institutions, authorities and legacy media is profound, not least among young Danes (DUF 2021).

2. Mobility, Democracy, and the Youth Perspective

Mobility must not simply be understood as the agency of something that moves from one point to another. John Urry, a pioneer in mobility research, identified several elements of mobility, such as the role of movement in social relationships, the synthesis of individual movement and systems of mobility and the interaction of those mobilities systems, and concerning implicit systemic power dynamics that facilitate some people to be mobile at all levels but prevent others from being so (Urry 2007). Although this is a very broad understanding of mobility (Duffy et al. 2020), it supports a diverse and multi-layered approach to mobility, which this article applies. It also indicates an intrinsic relationship between mobility and democracy.

It is ongoingly vital to investigate the development and integration of mobile devices such as smartphones and tablets in a democratic context, and as technological affordances for information and debate (Duffy et al. 2020; Hermanns 2008; Ling et al. 2020). Duffy et al. (2020) point to the dual understandings of ‘mobilities’ as a metaphor to illuminate the state of flux of news as substantial changes in mobile access and content. They note that ‘News has always been metaphorically mobile, moving from event to person to person’ but ‘Today, ‘mobile news’ is taken to mean news delivered on a personal, portable interactive device such as a smartphone’ (Duffy et al. 2020, p. 3) In this particular context, mobility can also be described as the ‘liquidity’ of news (with reference to Bauman’s book Liquid Modernity) or as a ‘metaphor to illuminate the state of flux’ of news, news production, and access (Duffy et al. 2020, p. 3).

“Democracy, as an idea and as a political reality, is fundamentally contested”, claimed David Held (2006, preface) in the updated version of Models of Democracy. Scholars from a variety of fields share this notion and offer a broad display of explanations of potential consequences and opportunities for societies and citizens as outcomes of democratic challenges and transformations (i.e., Dahlberg 2001; Dahlgren 2013; Papacharissi 2021; Schudson 1997). According to Held, ‘training’ citizens’ deliberative engagement is not mainly a matter of making citizens listen to politicians—it has a much broader, collective foundation, and embeds a level of agency that goes beyond debate (Held 2006, p. 316). The core elements of Held’s definition of deliberative democracy resonate with the normative perceptions of the young Danes that the study investigates, but they seem to clash with the everyday information and participation contexts of young Danish citizens.

Schudson argued, a decade earlier, that ‘conversation is not at the heart of democracy’ because democratic conversation is ‘not necessarily egalitarian, but it is essentially public, and if this means that democratic talk is talk among people of different values and different backgrounds, it is also profoundly uncomfortable’ (Schudson 1997, p. 299). This resonates with the experience of the young Danes that I have investigated. It also applies to the notion that ‘democracy sometimes requires withdrawal from conversation, withdrawal from common public subjects’. Also, ‘democracy may require withdrawal from civility itself’ and that citizens ‘shout’ through social movements, strikes, or demonstrations (Schudson 1997, pp. 307–8).

In terms of the youth perspective, Ohme et al. say that ‘Youth is a reference point that can reveal two important things: the past years of a cohort’s development and an outlook into the future’ (Ohme et al. 2022, p. 557). Furthermore, they discuss inter- and intragenerational aspects of changing realities of information and democratic participation. While the conditions that the study investigates are, to varying degrees, defined across generations, research (i.e., Colombo and Rebughini 2019; Mascheroni 2017; Mihailidis 2014) indicates that young people in particular experience and are exponents of radically transforming patterns of information access and opportunities for democratic engagement and participation. Young people are the bearers of tomorrow’s democracy, and it is vital to understand the dynamic conditions that form the foundation of their democratic perception and engagement (Held 2006; Mascheroni and Murru 2017; Mihailidis 2014; Papacharissi 2016).

3. Methods

Methodologically, the article’s research framework applies a multiple methods approach (Jensen 2012, p. 300; Schrøder 2012, p. 820) that couples results from a qualitative study conducted in 2021 and a representative survey from 2017. The findings from the survey are supplemented by publicly accessible results from the Danish2021 part of Reuters annual, globally distributed surveys on news use (Schrøder et al. 2021), Statistics Denmark, and The Danish Youth Council’s 2021 report about youth and democratic participation (DUF 2021).

The purpose is to triangulate the research perspectives on the phenomenon that the study investigates through the combination of data that describe trends with evidence of specific examples from the qualitative sample of the population in focus.

3.1. Dataset 1: Qualitative Interviews

3.1.1. Method

The 2021 study includes 16 in-depth, semi-structured interviews with 16–24-year-old Danes, conducted in connection to the project Youth, trust, information, and democracy, by the author and a research assistant.

The study strategically focuses on a broadly defined majority of young Danes, thus does not involve marginalized and/or vulnerable youth or political activists.

The 16 interview participants were selected strategically through a grid that was developed to ensure optimal symmetry in age and gender, while also ensuring diversity regarding location, education, and occupation. We found the participants through a snowball sampling method (Jensen 2012, p. 270), where we sent out invitations through secondary networks, social media, and other interview participants with specific information about interest in diverse age groups, gender, region, and education/occupation. Due to GDPR considerations, potential participants were asked to contact the researchers via e-mail or telephone. Hence, the researchers only communicated with young people who were willing to participate in the interviews (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of the interview participants 2021 study.

3.1.2. Measures

Age. Ideally, the age group would include 15–24-year-olds, which, at a general level, is how the United Nations delimit ‘youth’ or ‘young people’ for statistical purposes (United Nations 2021). This group can generally be subdivided into smaller groups (16–18, 19–22, 23–24) that are characterized by short life phases, defined by increasing experience and cognitive skills, education, occupation, and family context (Buckingham 2007).

Gender. The participants could report gender as ‘female’, ‘male’, ‘non-binary’, ‘other’, or ‘do not want to reply’. None of the interview participants announced their gender as other than ‘female’ or ‘male’; hence I use these terms in the article.

Region. We aimed for distribution of the interview participants between the capital area, other big cities, and outside these, in the five parts of Denmark. We obtained a relatively good distribution, but not optimal, as we did not find participants in Jutland. Education/Occupation. We strategically aimed for diversity among the interview participants based on education and occupation (see Table 1) because this in other studies tends to be a factor in regard to the impact of social and cultural capital on the information and reflexivity level (i.e., Buckingham 2007; Colombo and Rebughini 2019; Mihailidis 2014).

The interview guide included questions about information forms and channels; level of information and experience of being informed; social networks and activities to deal with the Covid-19 crisis; perceptions of and experience with politics and democracy; trust in information channels and informants; open-ended follow-up.

3.1.3. Analysis

The analysis of the qualitative data is based on a multi-layered thematic coding (Jensen 2012). This includes interview themes and sub-themes, specific individual participant replies, and finally, contextual relations (affinity mapping) between thematic appearances in the individual interviews.

3.1.4. General Findings

In the present context, the age group is relevant because young Danes are responsible for managing their digital citizenship from the age of 15. Additionally, multiple other studies, also conducted by the author, operate with the same age group. However, we could not find 15-year-old volunteers for the interviews, but some recently turned 16. This, again, aligns with the age group for the 2017 survey. In the context of the present analysis, we did not find significant diversities in the replies based on age.

More females than males participated in the interviews, which indicates the only gender-related diversity we could identify in the context of the present analysis: it is more difficult to persuade young males to participate in interviews than females. In the context of the present analysis, we did not find significant diversities in the replies based on location.

Education and occupation were the only areas where we found examples of diversity in the interviews, as participants with shorter education would express a lower self-confidence regarding information and debate level and engagement, compared to those with more extended educations and those whose parents were well-educated and engaged i discussion with their children. The interviews were conducted while Covid-19 regulations were still active.

The participants’ experiences from the lockdown were evident. Although most participants commented on the ‘online encounter fatigue’, the communication and establishment of trust worked well.

3.2. Dataset 2. Survey

3.2.1. Method

Kantar Gallup conducted the survey. The data collection took place in December 2017, based on a representative sample of the Danish population over 16 years, extracted from their GallupForum panel, through web interviews with an option of telephone reminders. The sample is representative of gender (male/female), age, region and education.

It included 1550 Danes. The confidence level is 95%, and the margin of error is 3%. The 16–24-year-olds constitute 118 of the total 1550 participants, which is not sufficient to subdivide this group by more than one background variable.

3.2.2. Measures

The survey comprises 19 questions about Danes’ use of social media, information practices, trust in information sources, and political participation. The reply options were either on a five-level scale from ‘always’ to ‘never’ regarding media use or on a seven-level scale from ‘not very’ to ‘very much’ regarding attitudes.

3.2.3. Analysis

The data for the 16–24 year-olds were extracted according to the questions in focus. The discrete (background) variables, age, gender, region, and education, were analyzed at the nominal level for a basic categorization of the results, and, following this, through ordinal ranking of the categories regarding the relevant questions, and presented in frequency tables.

3.3. Research Ethical Considerations

In the 2021 study, the data material was anonymized and stored on a safe server behind a firewall. The participants granted informed consent and they could withdraw their consent to participation at any point. In a Danish academic research context, written consent, respective approval by participants or their parents, is not required. Neither is the university ethics board’s approval of the research design and methods required. The research, however, follows The Danish Code of Conduct for Research Integrity (Ministry of Higher Education and Science 2014).

Kantar Gallup guaranteed the ethical precautions of the 2017 survey regarding the protection of participants’ privacy, methodological robustness, and data storage. Kantar Gallup reported the data collection to The Danish Data Protection Agency.

4. Results

The analysis of the 2021 interviews resulted in the clustering of findings around three core themes that can be denominated as conditions for the actual and metaphorical (Duffy et al. 2020) understanding of the mobility of the foundations of democracy.

4.1. Condition 1. Mobile Technologies and Services

The first condition regards the technological affordances for mobile democracy. These are at the core of radical transformations of young peoples’ news and information access.

This condition refers to the intersecting availability of technological mobile platforms, such as smart phones and tablets, in combination with the accessibility of online services that are available on and across these platforms (Hermanns 2008; Ling et al. 2020). It is not a new finding, but the number of access points through smart, mobile platform techs has radically increased over relatively few years (Duffy et al. 2020). The use of mobile technologies for accessing news exists in young Danes’ everyday life in combination with erratic encounters with traditional media technologies, such as print newspapers and magazines, television, and radio. Young people who possess and master a broad variety of technologies and services have potential access to all digital information formats, with adaptations that match the speed of online information, the affordances and restrictions of particularly mobile devices, and the interests and attention span of the users.

We did not ask about the general use of technological platforms in the 2017 survey. However, Statistics Denmark (2021) document in their survey on IT use in the Danish population that 97% of 15–34-year-old Danes go online via their smartphone. This is supported by the participants in the 2021 study, who all mentioned their smartphone as a default medium for casual information and for accessing news via apps or through pop-ups, when doing something else, and for social updating, which may contain elements of information exchange. Schrøder et al. (2021) confirm the preference of the smartphone as a platform for accessing news in a Danish context. In an international context, this is confirmed by multiple sources, i.e., Duffy et al. (2020) and Van Damme et al. (2020).

The use of the smartphone for multiple purposes through multiple access points is so obvious that the interview participants do not address this until prompted. When they think about it, they combine a casual erratic ‘whatever comes up by algorithmic decision’ approach with a strategic choice of platforms and services for specific purposes, i.e., some mention that they may prefer the laptop for tasks such as schoolwork, YouTube videos, or information search. Also, technological mobility facilitates concurrent uses of multiple platforms and services: ‘It is mostly the mobile because then I am watching something on my computer and then I check out Facebook on my mobile. Many people my age does that’. (9. Female, 19).

The 2017 survey shows that the 16–29-year-old participants subscribe to a comprehensive repertoire of social media with Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram, and YouTube as the most prominent choices. In 2017 Facebook was the most used social medium for reading news for 69% of the 16–19-year-olds and 67% of the 20–29-year-olds, and for reading other peoples’ updates, which 53% of the 16–19-year-olds and 77% of the 20–29-year-olds do. Very few of the young, however, write updates themselves, share content or news, or comment. Young people’s online activities tend to be relatively passive (and have always been so), and their abilities to exploit and qualify their online opportunities are different according to age, SES, level of individual self-efficacy. The challenges for many young people in reaching the higher levels of the ladder of online opportunities were, for example, documented by Livingstone and Helsper (2007, 2010). These challenges are still valid in 2021 according to the study, and to Schrøder et al. (2021).

The number of available services increases each year, resulting in a wider diversity of information channels. The 2017 survey did not include TikTok, but Statistics Denmark (2021) finds that 98% of the 15-year-olds subscribe to Tik Tok, Snapchat, or Instagram.

These services are also frequently mentioned in the 2021 interviews as sources for casual interest-based information. Another, semi-new option is the use of podcast via the smartphone. Schrøder et al. (2021) found that 56% of the 18–24-year-olds listened to a podcast during the past month. The combination of strategic and erratic information is possible through mobile technologies: ‘If I must search for information, which I do relatively often, I use the app DR News that has notifications’ (8. Female, 19). In this context, the search for information appears to be strategic but essentially provides what appears through the app. This underlines the important role of the technological preconditions for algorithmic ‘choices’ of content. (i.e., Cotter and Thorson 2022; Duffy et al. 2020). Online services can be described as mobile because they are instantly accessible across technological platforms independent of time and location, and because they provide opportunities for mobility of information. Ongoing innovations of ‘assisting’ technologies such as Bluetooth, advanced wireless headsets, and direct hyperlinks between bits of information promote the constant content accessibility and always on status through mobile technologies. This may preserve social and mental bubbles of privacy, which does not promote awareness and conversation in the physical space or online contexts. The affordances of mobile technologies contribute to the creation of fragmented contexts and practices for information, news, and communication, which again emphasizes the mobility of the foundations for democracy.

4.2. Condition 2. Mobile Information and Social Media

I automatically get a lot of information all the time when I am on social media... I also follow a lot of people. And I get ordinary information a lot from my friends. It has also become popular to share infographics on Instagram. Much is thrown into your face, and I also follow DR News, Politiken and politicians …(8. Female, 19)

Today, news is mobile in practice and metaphorically (Duffy et al. 2020). News production has changed towards fast production and extensive distribution points as addressed by, i.e., Bakker and de Vreese (2011) and Westlund and Bjur (2013). As the quote above demonstrates, media and societal organizations have, to varying degrees, integrated new digital information and communication systems as part of their outreach to young citizens, based on the rightful assumption that this group is digitally literate, has access to and uses digital media, and that digital and mobile information systems figure in their preferred options for engagement (Mascheroni and Murru 2017; Third et al. 2019). However, as described above, it cannot be assumed that young people have reached active participation and citizenship, which is the final stepping point of the ladder of online opportunities (Livingstone and Helsper 2007, 2010). Any citizen needs to be highly knowledgeable and digitally literate to reach this stage, and despite easy, almost infinite online access to information and participation, the obstacles and challenges for exploiting this for democratic participation are vital. During the interviews, the participants were asked to bring up examples of their knowledge when they, e.g., addressed political issues in a local, national or international context. As the interviews were semi-structured, they did not pursue a standard checklist for inquiring about specific knowledge. However, the general thematic design of the interviews prompted all participants to bring up examples of their knowledge about current issues and their attitudes based on their knowledge and experience. Interestingly, all participants but two expressed a lack of confidence in their own knowledge while demonstrating broadly represented elements of knowledge and solid knowledge of how to pursue further information and critical source evaluation.

The digitization of social institutions has significant consequences for the circulation and meaning of news and information among young citizens. While traditional information flows remain, they are now fully integrated with other forms of news “talk” in networked, digital, and relational communication environments (Kalsnes and Larsson 2018; Schrøder et al. 2021). Informative exchanges with friends are more important than those with formal actors in promoting informed citizenship and political engagement or withdrawal (DUF 2021; Mascheroni and Murru 2017; Segesten et al. 2022).

Young people actively discover and integrate alternative sources for being informed that do not adhere to traditional journalistic criteria (Cotter and Thorson 2022; Magin et al. 2022; Wunderlich et al. 2022). Thus, the variety and quality of sources and formats for news and information to which young citizens are exposed have changed radically in a process that dialectically intertwines with the development of technology platforms and services (Cumiskey and Hjorth 2013; Segesten et al. 2022; Westlund and Bjur 2013).

The findings point to three crucial levels of information mobility, with reference to, i.e., Ling et al. (2020) and Westlund and Bjur (2013). The first regards the kaleidoscopic supply of news and information channels and sources. The second is defined by the discrepancies between deliberate and incidental information access. The third level is the decrease of editorial and ideological coherence that young people can draw on in their news and information feed.

4.2.1. Mobility of News and Information Sources

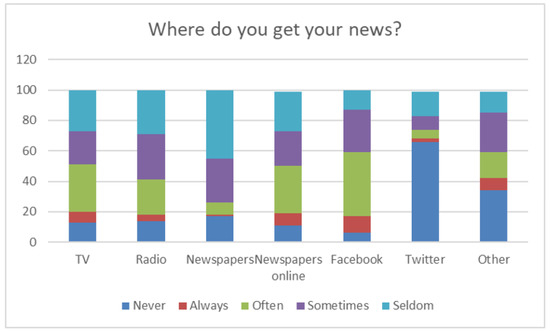

The 2017 survey reveals (Figure 1) that news and information access through social media (‘Facebook’ and ‘other’) are most prominent, followed by TV and online newspapers. The ‘other’ category covers multiple examples of other social media.

Figure 1.

News and information sources, 16–24-year-old Danes. Survey 2017. N = 118 (/1550).

This pattern is also valid in 2021. According to Schrøder et al. (2021), the most used sources for news, during the past week, among 18–24-year-olds were social media (58%) and TV channels’ online news sites (46%). Very few (6%) use traditional newspapers, while 37% use online newspapers.

It is not a new phenomenon to get your news via different platforms and in different formats. What is new is the amount and variety in platforms and the multitude and qualitative diversity of the content sources. ‘Right now, I listen to podcast a lot. And then on various social media, but I get more on international politics from them. Often in the format of satire. And then I catch up stuff from my parents’. (4. Male, 16).

It is vital to note that the importance of news media during the Corona-lockdown influenced the 2021 study. The interview participants address their sudden growing interest in news and political information in the beginning of the lockdown, in terms of the set-in of Corona information fatigue over time.

Most of the interview participants subscribe to news apps from major news organizations and receive notifications about new posts. Although subscribing to news apps demonstrates intentional interest in news, this organized pool of news blends into th indefinite stream of information from multiple sources of diverse origins. The sources may become imperceptible because the posts are so short and ephemerally passing on the small smartphone screen.

The 2021 interviews disclose that many participants consider social media such as Instagram, Snapchat, and YouTube useful sources for news and information when accessed from a smartphone (Cotter and Thorson 2022; Wunderlich et al. 2022). TikTok is mostly popular among the youngest participants, also found by Ohme et al. (2022) and Schrøder et al. (2021). The user-produced content entertains TikTok users, but they also describe TikTok as a deliverer of casual, untrustworthy videos. Some, however, find that TikTok serves as a source of information: ‘I often get kind of political information from TikTok, because videos on various topics come up, so I get a lot of information from there. And sometimes from YouTube’. (3. Female, 16)

A different direction in the information repertoire is, as mentioned, the increasing use of podcasts. They are mainly listened to in a kind of dual mobility modus, on the smartphone, on the go. A need for meaningful activities triggered the interest during Corona, when many young people took up individual activities such as long walks or runs. ‘I listen a lot to podcasts. I found one I really like. It’s quite satirical. … Politiken [newspaper] labelled it a chit-chat podcast. It’s two freelance journalists who talk to each other’. (4. Male, 16)

The exciting point about podcasts is that some, although varying much in quality and professionalism, offer longer formats of in-depth topics that include research, agonistic positions, new insights, and pointers for debate. The topic and approach in podcasts are often popular and personal, but some provide critical journalistic perspectives that may inspire reflexivity and discussion: ‘Right now, I follow the news on the kids in those refugee camps, because it came up in several of the media I interact with–me and my parents talked about it, but I also heard about it in the podcast and my friends talk about it’. (4. Male, 16)

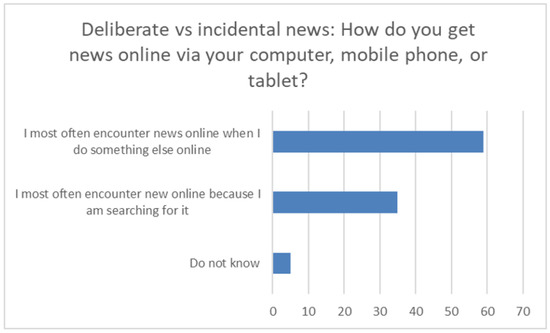

4.2.2. Deliberate versus Incidental Access

Young people encounter a challenge in their struggle to be informed because they get a large proportion of their news incidentally, when they are doing something else online (Figure 2). This is also noted by, i.e., Van Damme et al. (2020); Westlund and Bjur (2013); de Zúñiga et al. (2017).

Figure 2.

Deliberate vs incidental news. 16–24-year-old Danes. Survey 2017. N = 118 (/1550).

The 2021 interviews outline the picture: ‘I am watching what is happening around. You get around reasonably just by being on Facebook because all sorts of news come up there’. (11. Male, 20). What are the implications of getting the main proportion of one’s news when doing something else? The terms ‘pop up’, ‘casual’, and ‘scrolling’ reappear in the interviews. Often the information bits pass without encouraging in-depth focus and attention, which again challenges the establishment of a coherent understanding of a problem and arguments about it. ‘A lot of it is casual information I just happen to read on social media …–if a bomb exploded you read a bit, ’I didn’t know that’ish’, then you get news like, more casually’. (2, Female, 16). Duffy et al. (2020) also discuss this notion of the flux of mobile information.

Any news may be better than none, and the incoming stream of information, from multiple sources may deliver little triggers for attention and interest and bits for a larger, coherent picture. A positive finding is that some participants follow up on the bits of in-formation that they are interested in

Then something pops up on Facebook, among other stuff, and then I hear something and then I must check it out. … If we discuss something and I find it inter- esting I often look for more information about what we were talking about.(9. Female, 19)

4.2.3. Editorial and Ideological Coherence

An essential consequence of the immense bricolage of information bits from diverse sources and of varying quality is that instruments for building coherence are to a large degree missing or difficult to establish. Traditional editorial and ideological coherence is missing because the reception of the bits of information does not readily refer to a coherent frame of understanding, logic, and values. This is not an argument for a return to the old party press system, where one reads a particular newspaper according to social background, nor to a time when everyone, in a Danish context, would watch the same television channel. However, when consistent societal reference points are missing, and a consistent frame of understanding is lacking, it is up to the young people to connect the dots and establish coherence and meaningfulness out of chaos.

The considerations about the absence of editorial or ideological coherence can refer back to the presentation in the introduction of the metaphorical meaning of mobility. It is easy to be drawn to and to fluctuate between different ‘sub-publics’, or even small parts of these. Bruns and Burgess (2015) discuss this fragmentation of the public sphere as hashtag publics and calculated publics, with a focus on the central role of hashtags in public debate at all levels. Møller Hartley et al. (2021) address ‘calculated publics’ (with a reference to Gillespie 2014) as one of more outcomes of datafication and its transformative effects on the formation of publics. Magin et al. (2022) describe fragmentation as a multilevel and complex phenomenon that is very difficult to overcome, among other causes due to the personalized content delivered by algorithm-driven sources such as social media (Bennett 2012; Magin et al. 2022).

Papacharissi outlines how what can be labelled ‘networked publics’ ‘come together and/or disband around bonds of sentiment’, and she describes them as ‘affective, convening across networks that are discursively rendered out of mediated interactions. They assemble around media and platforms that invite affective attunement, support affective investment, and propagate affectively charged expression, like Twitter’ (Papacharissi 2016, p. 308). However, for the young Danes in the research behind this article, Instagram and TikTok rather than Twitter are media for affective meetings in private, secluded groups. However, the outcome is, across various labels and identifications, that the young are left behind and without the bigger picture. Fragments of the picture fluctuate and pass ephemerally by on the small screen.

I find it really stressful and annoying to have to think about all kinds of things I didn’t look up myself. You receive so many impressions and when people share infographics on Instagram … They are powerful tools, but you can also stress out because there are so many things you must relate to and there are two lines about a crazy world problem, … and it is like that for every second story you click through.(8. Female, 19)

As we saw, an essential proportion of young Danes’ news is provided by online news media (Schrøder et al. 2021). These, however, tend to contribute to the lack of overview and cohesion, probably involuntarily, as young people mostly subscribe to news apps that deliver headlines with links to more information. News media fall into the perception that young people are only interested in catching topics and one-liners. Participants in the 2021 interviews are critical about the lack of help from media institutions in their attempt to be better informed:

As a young person I feel mega misunderstood. It’s as if they think, the more clickbait the more we can get young people to follow. I would like to follow when there is content that is worth listening to. I grew up with clickbait, I know what it is. It’s a myth that you only have five secs to catch young peoples’ attention.(8. Female, 19)

Most of the interview participants express an interest in being informed, generally and as part of their civic duty. According to the 2017 survey, the young participants to a more considerable degree than older participants report that they fact-check information when it is not obviously true or false. Thus, awareness of and interest in the quality of news and information does exist. This indicates a balance, although a wobbly one, between stability (the need to be ‘traditionally’ informed) and mobility (the fascination of the fragmented, incidental, and entertaining information from social media). The participants struggle for meaningfulness in the messy information palette, as with this girl who is glad when she can connect the dots to usefulness:

‘It is quite true, that you find a fragment here and there, so, when it comes up as a topic, you can say ’hey, I read 12 lines about that the other day’.(6. Female, 18)

4.3. Condition 3. Mobile Engagement and Participation

The third condition addresses the mobile patterns of motivations and agency regarding political engagement and democratic participation. ‘Political’ and ‘democratic’ in this context do not solely refer to formal engagement and participation but are broadly defined. None of the 16 participants in the 2021 interviews was member of a political party while some were members of NGOs (i.e., Save the Children or Greenpeace), other organizations (i.e., scouting, choir, theatre), or sports clubs. This is supported by DUF’s democracy analysis (DUF 2021). However, the majority, according to the 2021 studies and the DUF-survey participate in other, often informal, non-public ways, and they have opinions about current affairs and into which direction society should develop in Denmark and internationally. In the context of the third condition, the focus is also on three aspects of mobility and democracy: ad hoc engagement and participation from cause to cause; the contexts of participation and debate; and the aspects of changing opinions.

4.3.1. Ad Hoc Engagement

The data indicate common trends regarding political topics that interest the participants and the participants in the DUF survey. Corona, environment/sustainability, and human rights issues are at the forefront, with a current focus on refugee rights, Black Lives Matter, Corona, and citizen rights, questions of political realities in the US, censorship in China, etcetera. The interview participants are, to varying degrees, knowledgeable at a general level and interested in being so, despite some saying that they know little or are not interested in politics. One example is an interview participant who says that they do not discuss politics at the family dinner table, but they talk about what happens. This demonstrates a narrow definition of politics that disregards local and personal interests, as well as informal exchange and discussions as potential political agency.

According to Held (2006, p. 200), ‘The views ‘aired’ in politics and the media intersect in complex ways with daily experience, local tradition and social structure’. This is an important notion for understanding democratic deliberation that may function in more local contexts compared to a formal political level. Media, particularly social media, significantly influence this process, including that of shifting foci and interest. However, to say that interests and opinions are media-created is a simplification (Kalsnes and Larsson 2018; Third et al. 2019; Vromen et al. 2016b). A complex and highly dynamic system of sources informs and inspires to develop interest and opinions in the local contexts as well as in major political issues. However, mobile, online, and social media do play a vital role in the fragmentation of information and the challenge of coherent connections. Again, it is obvious to refer to research and theories on fragmented publics, described as, i.e. hashtag publics (Bruns and Burgess 2015), calculated publics (Møller Hartley et al. 2021), and affective publics (Papacharissi 2016).

It is evident that the inputs from friends, family, and teachers are vital to forming interests and opinions. Fragments of news and information delivered by social media may be discussed by friends and family and in school. Our participants pre-exist their background, age, and cognitive maturity. Inspiration for engagement takes place spot-wise, casually, and close to the context apart from school curricula, which is or has been highly relevant for our participants. It is reasonable to talk about the presence of value pluralism (Held 2006, p. 316), translated to a practical level, where deliberation involves discussing and evaluating moral and social values. It seems that the ‘choice’ of interest current causes, and the relatability of these for the individual interview participants reflects the personal, emotional, and moral considerations and preconditions for engagement (Bennett 2012; Colombo and Rebughini 2019; Vromen et al. 2016a).

As described, most of the participants revealed that they are interested in and have strong opinions about the larger issues such as human interest topics, climate, environment and sustainability, or the large-scale consequences of the pandemic, while they fluctuate between different causes, according to the current newsfeeds and inputs from friends and family. The major challenge, however, appears also in this context to be prevalent confusion about foundational opinions and ideological coherence.

4.3.2. Contexts of Participation and Debate

The participants in the 2021 interviews all, to varying degrees, discuss current topics, as outlined above. Not all, however, would label the topics ‘political’, and none are generally engaged in public debate. All participants say that they prefer to discuss with family or friends, offline, in safe spaces, although a few would sometimes enter online discussions on social media, but not feeling confident about it. This is an expression of stability (staying in the safe context) over mobility (moving between information contexts). All the i nterview participants have opinions, but few are confident to share them publicly, with people they do not know, online or offline. There are several reasons why this is the case. The results from the 2017 survey respectively the DUF survey confirm these reasons. Notably, the most prominent argument is that almost half of the participants say that it is ‘very true’ that they want to avoid negative consequences of participation and more than a third agrees with this almost entirely or somewhat, which underlines the findings from the interviews. Mascheroni and Murru (2017) discussed similar finding.

4.3.3. Aspects of Changing Opinion

The quality of debate is the exchange of arguments based on knowledge and insights and potentially changing your opinion or impacting others’ opinion because of this process. This potential change or impact is a healthy element in the foundation of deliberative democracy (Dahlberg 2001; Held 2006). The 2017 survey shows that 14% of the 16–35-year-olds who participate in debate at any point always or often change their opinion, while 24% do so sometimes and 62% seldom or never change their opinion.

Some of the interview participants say they are pretty fixated on opinions, but most explain that they often or sometimes change their opinion when they hear or see some- thing convincing. This may, of course, be an indicator of a healthy debate where the best or most convincing argument wins. If the change of opinion is connected to following up on facts and finding more information, it is a positive point of departure for future democracy. It may also, however, indicate opportunism, fluctuating/ephemeral reflections and opinions, or insecurity in own knowledge and beliefs. Wunderlich et al. (2022) also address ‘a general difficulty in forming their own opinions on current affairs, mainly because they feel that they are inadvertently influenced by social media’ (Wunderlich et al. 2022, p. 582).

The opposite position, the fixed opinions, may be perceived as positive if they are based on strong combinations of information, experience, insights, and dedication. Magin et al. (2022) argue that fixed opinions, based on individual, personal arguments may be cause of social disintegration, because the common reference frame is missing. The interviews, however, reveal various, often interconnected, constellations of causes, ranging from avoiding online news and debates over resistance to consideration of opposing arguments and opinions to debate online in secluded, potentially echoing, spaces and to insecurity regarding engaging in debate. Resistance towards requirements of a certain level of knowledge and ability to debate comes up in some interviews, as expressed by a 19-year-old female who claims that she will not change her opinions because she cannot bother to follow anyone on social media that she disagrees with (8. Female, 19). Another interview participant comprehends the core of the challenge of engaging in difficult debates like this:

You can get really tired from reading long comment threads, and in particular when it’s for example about the refugee crisis that is up in the debate a lot. There are attitudes on both sides that have valid reasons one way or another, often something about priorities, and it can make the minds of many people boil. So, I try to stay away from … hot topics you might call it. I follow from a distance, but I do not feel like actively going into something like that.(13. Male, 22)

It is evident that the young Danes in the 2021 study adhere to ad hoc engagement and participation from cause to cause, and that they are not very open towards engaging in public debate but stay within their safe spaces or in anonymous public, offline spaces. This adds important aspects to understanding the consequences of fragmented information practices and limitations of democratic conversation as expressions of mobile democracy.

5. Discussion

The three conditions that the article presents reveal that the multiple aspects of mobility regarding democratic agency, each and across the conditions create opportunities and concrete challenges for young Danes’ efforts to be democratic citizens. It is vital to understand what the actual challenges are, but also to understand how traditional ideas about democracy are fundamentally contested (Held 2006), and how conceptual and strategic thinking about democratic innovation among young citizens may be enforced and supported. It is evident from the analysis of the three conditions that an overarching element of the challenges that the young Danes in the study behind the article encounter is that they must be responsible for the never-ending necessity for choosing between platforms, services, excessive content, and agency/participation. They are responsible for curating the quality of the currents of information they achieve, for connecting the dots and creating coherent meaning and arguments, and for positioning themselves in political debate or withdrawing from it. This is not new, but the complexity and extension of options is ever-growing.

An essential aspect of this challenge is the increasing individualization of what one gets, decided by preferred platforms, services, and content, enforced by the algorithmic memory that decides what comes up based on previous choices. This does not effortlessly facilitate collective thinking but must be learned: ‘Learning to place one’s own desires and interests in the context of those of others should be an essential part of every child’s education. Thinking in a way that is sensitive to others’. (Held 2006, p. 316)

Being responsible for one’s own choices and agency is part of growing up and into democratic citizenship.

However, if the process is not qualified, and if the pressure on young citizens is not lifted through relatable options/alternatives, training, and constructive guidance, the risk is that a generation of future democratic citizens will give up and go with the flow. They may react to the messiness and overwhelming multitude of information bits and information sources, refrain from pursuing more in-depth information and withdraw from the cacophony of information (Colombo and Rebughini 2019; Cotter and Thorson 2022). Hence, they would miss vital opportunities to form opinions, engage, and have a voice in democratic processes (Schudson 1997; reference anonymized). This is a demonstration of how mobile democracy is formatted and enacted through the practices and perceptions of young citizens, for all the reasons that are outlined in the article. As other scholars also find (i.e., Colombo and Rebughini 2019; Cotter and Thorson 2022; Wunderlich et al. 2022), young citizens navigate and manage the different contexts of mobility, and they often know more about society, politics, and democracy than they believe. However, exactly this lack of self-confidence is a major challenge, an obstacle for establishing coherent meaning and using it in a deliberative, democratic process.

It is a significant challenge for young citizens that they must ongoingly evaluate their news and information diet for quality and decide which sources to trust and which not to. The indefinite number of sources that are mixed up in the incoming information that they encounter, release a need for continuous evaluation of what is purely subjective, emotional, entertainment, and what is factual, substantiated and reliable, and how to use the diverse forms of information. While TikTok and similar services can be said to motivate fast, erratic skating on the surface, constantly moving between bits of content, i.e., professional podcasts invite in-depth consideration. A vital question is how young people learn how to distinguish between content from TikTok and edited news sources, and to prioritize when needed.

If deliberative democracy is based on citizens’ informed deliberation of social and political conditions, a much more critical perspective on the quality of all kinds of information and sources for content is needed. On the positive side, the building foundation for democratic participation is present, as the evidence points towards the presence of awareness of the importance of fact-checking and critical source evaluation, and an interest in being well informed. According to Held (2006, p. 316) ‘a strong civic education agenda [is integral] to help cultivate the capacity for public reasoning and political choice’. In addition, i.e., Ohme et al. (2022) and Third et al. (2019) argue for the important role of civic education.

An important finding is the infeasible challenge for young people to connect the dots of endless, fluctuating bits of information, extensively from social media, and the attempt to create coherent meaning and arguments. (Van Damme et al. 2020; Wei 2020; de Zúñiga et al. 2017). It is illusionary to believe that the erratic array of information that young people encounter will change radically. Held claims that ‘[the evidence highlights] the prevalence of value dissensus and of marked divisions of opinion among many working people; a fragmented set of attitudes is a more common finding than a coherent ‘manufactured’ standpoint’ (Held 2006, p. 256). I continue to think of editorial and ideological coherence as tools for qualitative building of arguments, at least if better options are not developed. There could, however, be opportunities and freedom in the liberation from editorial and ideological frames of reference as openings towards a nuanced, critical view on society and democratic citizenship. Hence, a focus on developing tools for critically dealing with the present forms of news and information and for connecting the dots and finding the arguments are vital. Schools are doing an important job already, but other institutions such as news media and the political level must also do their part.

A final, fundamental question that is connected to the mobility of news and information and to young citizens’ mobility, in practice and metaphorically, is the role of conversation and fear of debate. The conversation about current issues around the dinner table and with a few trusted friends is good. However, experience and opinions must be deliberated outside the safe walled garden of family and friends to carry weight in the democratic process that gives those in charge a real chance to make decisions based on collective democratic deliberation. Leaving the walled garden of the family and friends discussion space for participation in public debate can, according to Schudson (1997), quoted in the introduction, be uncomfortable, not least when the deliberative conversation is not equal. A way forward would be to exploit the benefits of mobile access to information and to find ways to open the gates between the walled gardens and public debate to let arguments flow between young citizens, social institutions, and decision-makers.

6. In Conclusion—Mobile Foundations of Democracy—What to Build On?

The options of finding sustainable strategies for addressing and solving these conditional challenges for democratic agency among young citizens seem infeasible, but there are multiple interdependent ways around this: The most important realization is that there is among average young Danes a high degree of democratic interest and erratic but existing knowledge about society and political issues to build on, be it with a point of departure in local contexts. Local contexts can be important, safe starting points for motivating ideas about society and one’s role and opportunities as a democratic citizen. Papacharissi mentions the need for more plurality and representational equality because this would ‘help citizens connect with elected officials and find ways to be more engaged and less skeptical’ and she continues ‘The problem, I find, is not one of apathy and disillusionment. It is one of citizens striving to be agonistic in a world that invites them to be antagonistic’. (Papacharissi 2021, p. 75). A reasonable way forward for the political institutions and others who oversee the civic education of young people would be to put more emphasis on respecting and accommodating different experiences and supporting young citizens’ wish to be informed, to debate, to reason, to be heard in inclusive ways that are respectful of collective and individual conditions and experiences. In short, it is necessary to build on all good incentives and to support young peoples’ positive democratic self-confidence, vitally through exploiting and developing the opportunities of a broad and unlimited access to information and interaction through mobile and social media.

Held (2006) considers that deliberative democracy may be the way forward for democratic development but adds that this model is still being deliberated. Schudson claims that what distinguishes democratic conversation as a condition for deliberative democracy is not that it is equal but that it is public and that it is inclusive (Schudson 1997, p. 299). The point is that democracies must always be innovatively deliberated to facilitate a constant qualification of the elements of deliberation as a foundation for democracy that adapts to the concrete local, historical, social, and cultural context. In consequence, it is not necessarily negative that the foundation of democracy is mobile, but it depends on whether the mobility enables a dynamic innovation of democratic institutions, practices, and discourses.

The contribution of this article comes with some limitations. The first regards a methodological issue: the article describes general patterns that are based on representative data, and these are unfolded and given contextual strength through the in-depth analytical findings. However, the two main data sets were collected four years apart. The intentional design of the 2021 study to align with the 2017 survey counters potential significant issues with drawing on both data sets for the analysis. The inclusion of publicly accessible data from the same year as the qualitative study further supports the value of the results. Second, the article applies a strategic focus on, with a potentially negative connotation, ‘average’ young Danes because we need to know more about this vast majority and their experiences and considerations; further studies should involve, e.g., activists, socially marginalized, or vulnerable youth, to bring forward what applies explicitly to these groups, and how this may challenge the established normative values in potentially other directions than the present work does. Including other groups would also help frame what characterizes ‘average’ youth.

However, the article points to several questions that could lead to future challenges of a conceptual basis for discussion of mobile democracy as a phenomenon and a condition for democracy and citizen participation.

Funding

This research received no external funding or grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as it is not required in a Danish context to have the university ethics board’s approval of the research design and methods. The research, however, follows The Danish Code of Conduct for Research Integrity (Ministry of Higher Education and Science 2014).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to part of it (the 2017 survey) being obtained in collaboration with a third part. The 2021 interview data is not publicly available due to the qualitative form. Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: DUF Demokratianalysen and here: Schrøder et al. Danskernes brug af nyhedsmedier 2021.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Bakker, Tom, and Claes Holger de Vreese. 2011. Good News for the Future? Young People, Internet Use, and Political Participation. Communication Research 38: 451–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, WLance. 2012. The Personalization of Politics: Political Identity, Social Media, and Changing Patterns of Participation. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 644: 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns, Axwl, and Jean Burgess. 2015. Twitter hashtags from ad hoc to calculated publics. In Hashtag Publics: The Power and Politics of Discursive Networks. Digital Formations, 103. Edited by Nathan Rambukkana. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, pp. 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham, David. 2007. Introducing Identity. In Youth, Identity, Digital Media. Edited by David Buckingham. Cambridge: The MIT Press, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, Enzo, and Paola Rebughini. 2019. A Complex uncertainty. Young people in the riddle of the present. In Youth and the Politics of the Present. Coping with Complexity and Ambivalence. Edited by Enzo Colombo and Paola Rebughini. London: Routledge, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, Kelley, and Kjerstin Thorson. 2022. Judging Value in a Time of Information Cacophony: Young Adults, Social Media, and the Messiness of do-it-Yourself Expertise. The International Journal of Press/Politics 27: 629–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumiskey, Kathleen Mae, and Larissa Hjorth. 2013. Between the Seams. Mobile Media Practice, Presence and Politics. In Mobile Media Practices, Presence and Politic. The Challenge of Being Seamlessly Mobile. Edited by Kathleen Mae Cumiskey and Larissa Hjorth. London: Routledge, pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg, Lincoln. 2001. The Internet and Democratic Discourse: Exploring the Prospects of Online Deliberative Forums Extending the Public Sphere. Information, Communication & Society 4: 615–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgren, Peter. 2013. The Political Web. Media, Participation and Alternative Democracy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- de Zúñiga, Homero Gil, Brian Weeks, and Alberto Ardèvol-Abreu. 2017. Effects of the News-Finds-Me Perception in Communication: Social Media Use Implications for News Seeking and Learning About Politics. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 22: 105–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DUF–Dansk Ungdoms Fællesråd. 2021. Demokratianalysen 2021. Epinion for DUF. Available online: https://duf.dk/fileadmin/user_upload/Editor/documents/DUF_materialer/DUF_Analyser/Demokratianalysen_2021.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Duffy, Andrew, Rich Ling, Nuri Kim, Edson Tandoc Jr., and Oscar Westlund. 2020. News: Mobiles, Mobilities and Their Meeting Points. Digital Journalism 8: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunati, Leopoldina. 2003. The mobile phone and democracy: An ambivalent relationship. In Mobile Democracy. Essays on Society, Self and Politics. Edited by Kristof Nyíri. Vienna: Passagenverlag, pp. 239–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, Tarleton. 2014. The relevance of algorithms. In Media Technologies. Edited by Tarleton Gillespie, Pablo J. Boczkowski and Kirsten A. Foot. Boston: MIT Press, pp. 167–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, David. 2006. Models of Democracy, 3rd ed. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hermanns, Heike. 2008. Mobile Democracy: Mobile Phones as Democratic Tools. Politics 28: 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Klaus Bruhn, ed. 2012. A Handbook of Media and Communication Research: Qualitative and Quantitative Methodologies, 2nd ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kalsnes, Bente, and Anders Oluf Larsson. 2018. Understanding News Sharing Across Social Media. Journalism Studies 19: 1669–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Rich, Leopoldina Fortunati, Gerard Goggin, Sun Sun Lim, and Yuling Li, eds. 2020. Introduction. In The Oxford Handbook of Mobile Communication and Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, Sonia, and Ellen Helsper. 2007. Gradations in digital inclusion: Children, young people and the digital divide. New Media & Society 9: 671–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, Sonia, and Ellen Helsper. 2010. Balancing opportunities and risks in teenagers’ use of the internet: The role of online skills and internet self-efficacy. New Media & Society 12: 309–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magin, Melanie, Stefan Geiß, Birgit Stark, and Pascal Jürgens. 2022. Common Core in Danger? Personalized Information and the Fragmentation of the Public Agenda. The International Journal of Press/Politics 27: 887–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascheroni, Giovanna. 2017. A Practice-Based Approach to Online Participation: Young People’s Participatory Habitus as a Source of Diverse Online Engagement. International Journal of Communication 11: 4630–51. [Google Scholar]

- Mascheroni, Giovanna, and Maria Francesca Murru. 2017. “I Can Share Politics But I Don’t Discuss It”: Everyday Practices of Political Talk on Facebook. Social Media + Society 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihailidis, Paul. 2014. Media Literacy and the Emerging Citizen. New York: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Higher Education and Science. 2014. The Danish Code of Conduct for RESEARCH Integrity. Available online: https://ufm.dk/en/publications/2014/the-danish-code-of-conduct-for-research-integrity (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Møller Hartley, Jannie, Mette Bengtsson, Anna Schjøtt Hansen, and Morten Fischer Sivertsen. 2021. Researching Publics in Datafied Societies: Insights from Four Approaches to the Concept of ‘publics’ and a (Hybrid) Research Agenda. New Media & Society, 14614448211021045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohme, Jakob, Kim Andersen, Erik Albæk, and Claes Holger de Vreese. 2022. Anything Goes? Youth, News, and Democratic Engagement in the Roaring 2020s. The International Journal of Press/Politics 27: 557–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papacharissi, Zizi. 2016. Affective publics and structures of storytelling: Sentiment, events and mediality. Information, Communication & Society 19: 307–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papacharissi, Zizi. 2021. After Democracy. Imagining Our Political Future. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrøder, Ki. Christian. 2012. Methodological pluralism as a vehicle of qualitative generalization. Participations: Journal of Audience & Reception Studies 9: 798–825. [Google Scholar]

- Schrøder, Kim, Mark Blach-Ørsten, and Mads Kæmsgaard Eberholst. 2021. Danskernes Brug af Nyhedsmedier 2021 (The Danish Populations Use of News Media 2021). Report. Roskilde: Center for Nyhedsforskning, Roskilde University. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schudson, Michael. 1997. Why conversation is not the soul of democracy. Critical Studies in Mass Communication 14: 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segesten, Anamaria Dutceac, Michael Bossetta, Nils Holmberg, and Diederick Niehorster. 2022. The cueing power of comments on social media: How disagreement in Facebook comments affects user engagement with news. Information, Communication & Society 25: 1115–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stald, Gitte. 2007. Mobile Monitoring. Aspects of risk and surveillance and questions of democratic perspectives in young people’s uses of mobile phones. In Young Citizens and New Media: Strategies of Learning for Democratic Engagement. Edited by Peter Dahlgren. London: Routledge, pp. 205–25. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Denmark. 2021. It-Anvendelse i Befolkningen–2021. Copenhagen: Statistics Denmark. Available online: https://www.dst.dk/Site/Dst/Udgivelser/GetPubFile.aspx?id=39431&sid=itbef2021 (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Third, Amanda, Philippa Collin, Lucas Walsh, and Rosalyn Black. 2019. Young People in Digital Society: Control Shift. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. 2021. Definition of Youth. Available online: https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/documents/youth/fact-sheets/youth-definition.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Urry, John. 2007. Mobilities. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme, Kristin, Marijn Martens, Sarah Van Leuven, Mariek Vanden Abeele, and Lieven De Marez. 2020. Mapping the Mobile DNA of News. Understanding Incidental and Serendipitous Mobile News Consumption. Digital Journalism 8: 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vromen, Ariadne, Brian D. Loader, and Michael A. Xenos. 2016a. Beyond Lifestyle Politics in a time of crisis?: Comparing young people’s issue agendas and views on inequality. Policy Studies 36: 532–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vromen, Ariadne, Brian D. Loader, Michael A. Xenos, and Francesco Bailo. 2016b. Everyday Making through Facebook Engagement: Young Citizens’ Political Interactions in Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States. Political Studies 64: 513–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Ran. 2020. Mobile Media and Political Communication: Connect, Communicate, and Participate. In The Oxford Handbook of Mobile Communication and Society. Edited by Rich Ling, Leopoldina Fortunati, Gerard Goggin, Sun Sun Lim and Yuling Li. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 229–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westlund, Oscar, and Jakob Bjur. 2013. Mobile News Life of the Young. In Mobile Media Practices, Presence and Politic. The Challenge of Being Seamlessly Mobile. Edited by Kathleen Mae Cumiskey and Arissa Hjorth. London: Routledge, pp. 180–97. [Google Scholar]

- Wunderlich, Leonie, Sascha Hölig, and Uwe Hasebrink. 2022. Does Journalism Still Matter? The Role of Journalistic and non-Journalistic Sources in Young Peoples’ News Related Practices. The International Journal of Press/Politics 27: 569–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).