Sustainable Development and Evaluation of Natural Heritage in Protected Areas: The Case of Golija Nature Park, Serbia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

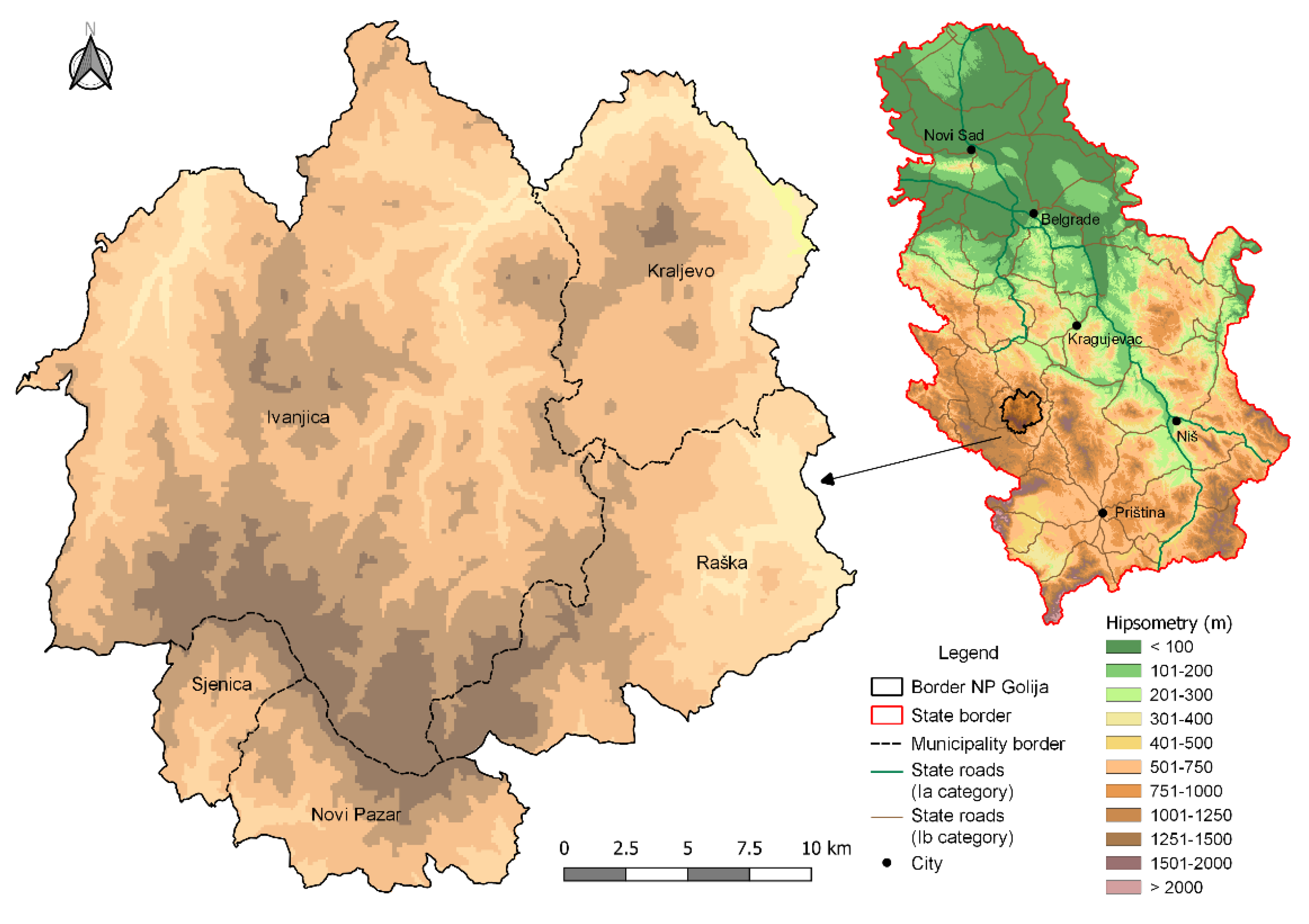

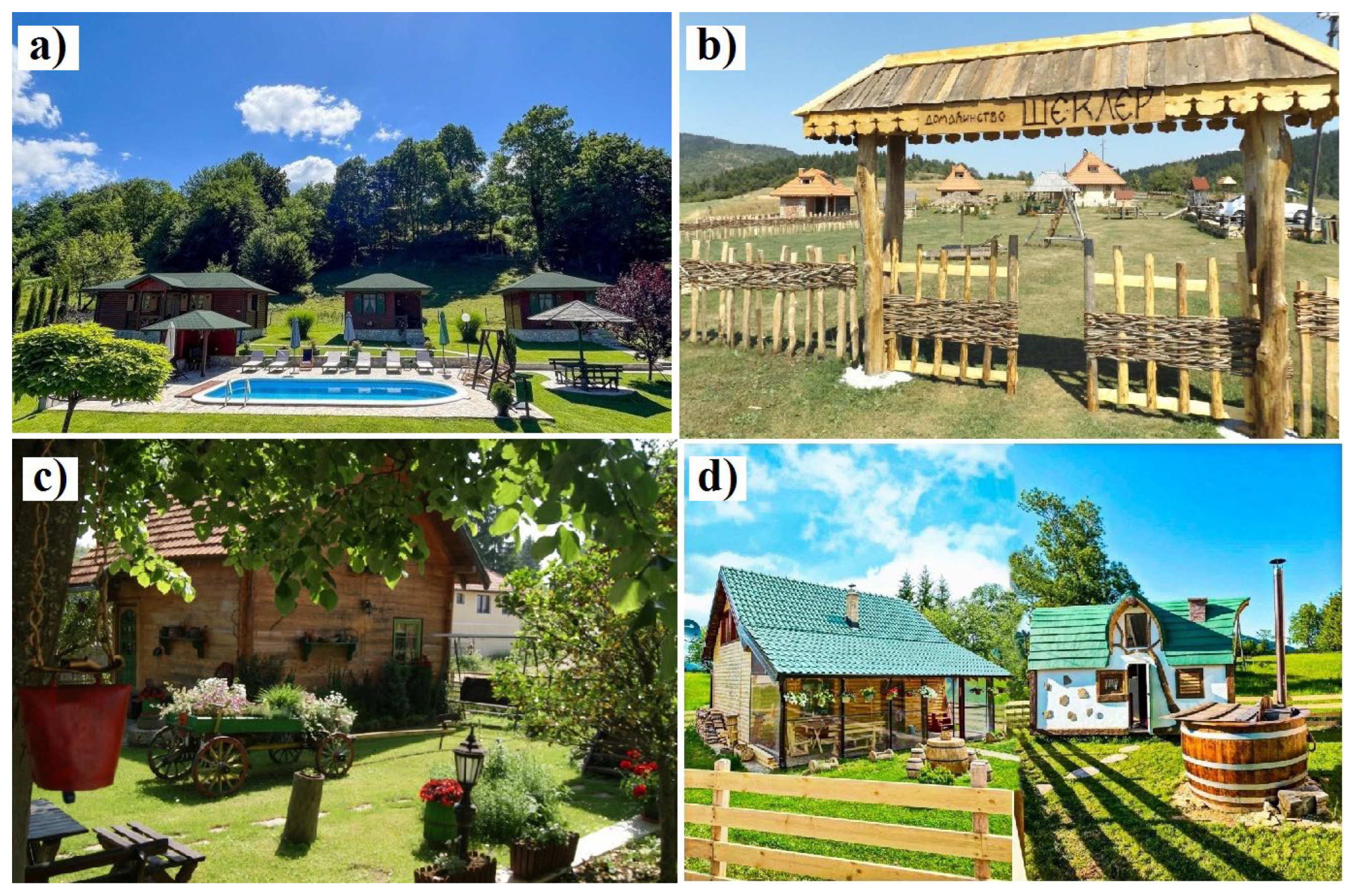

2.1. Research Area

2.2. Methodological Framework

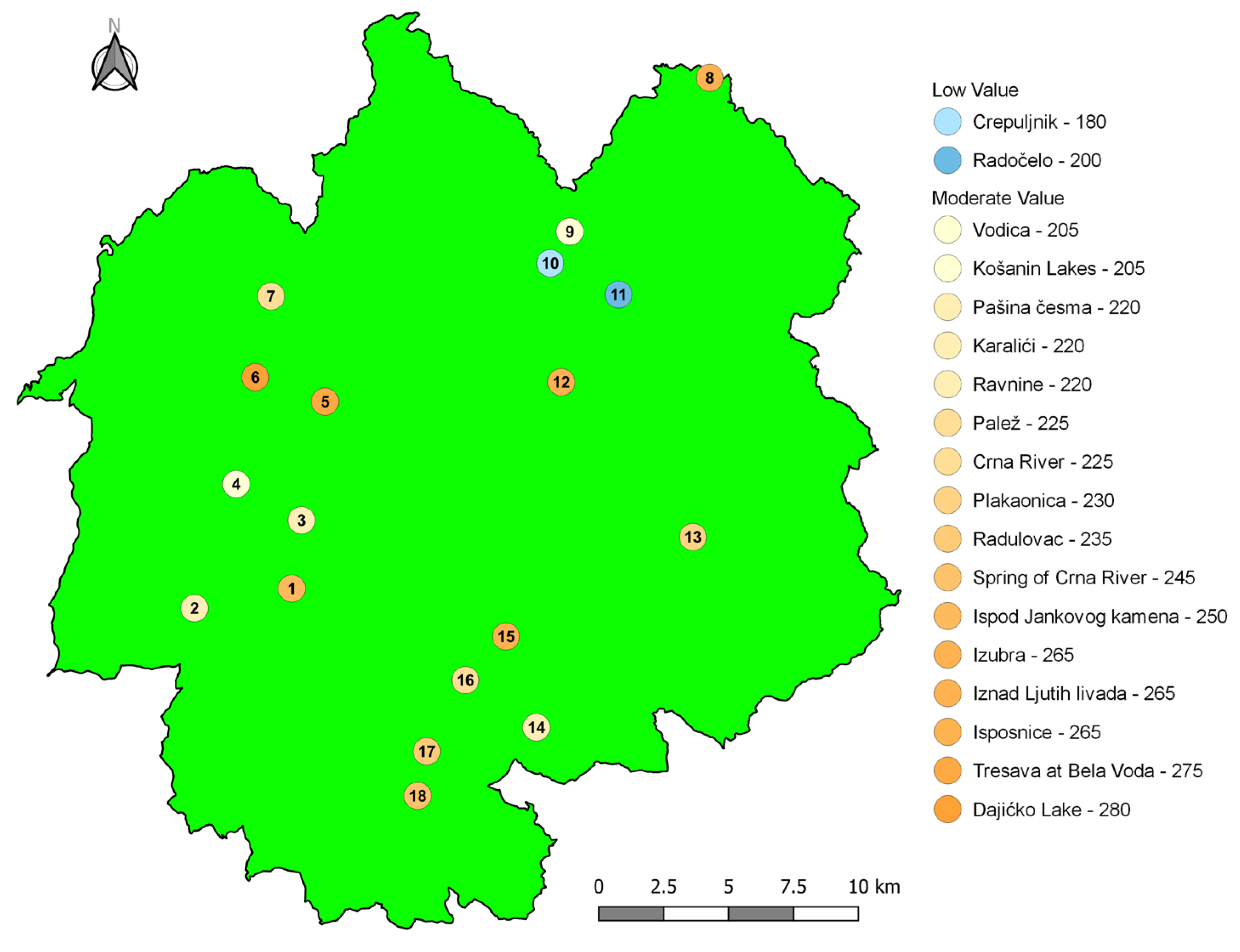

2.2.1. Quantitative Assessment of Potential Tourism Use (PTU)

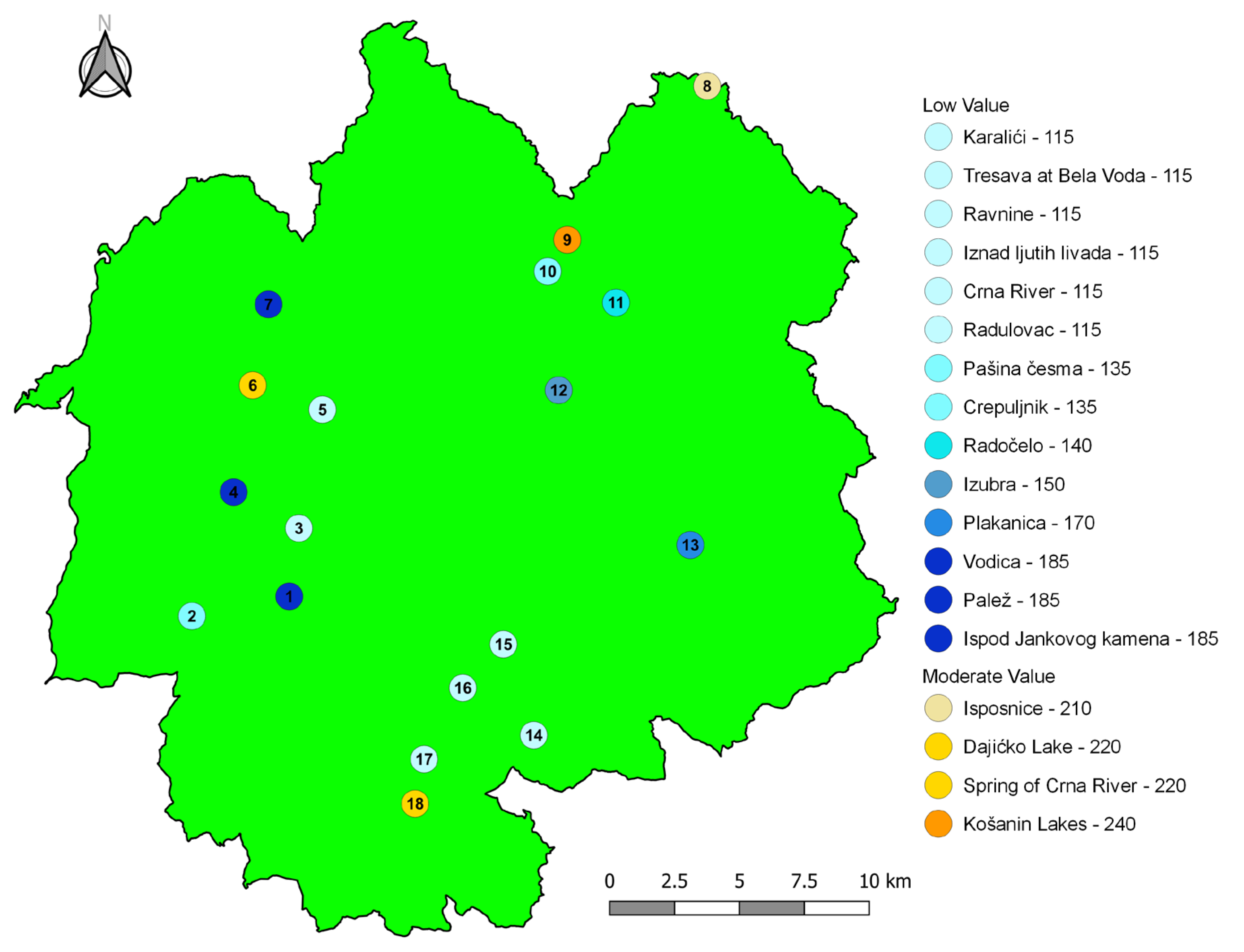

2.2.2. Quantitative Assessment of Degradation Risk (DR)

3. Results

4. Discussion

- -

- The site is located in a settlement with more than 100 inhabitants per km2 (4 points);

- -

- The site is located in a settlement with 25–100 inhabitants per km2 (3 points);

- -

- The site is located in a settlement with 10–25 inhabitants per km2 (2 points);

- -

- The site is located in a settlement with fewer than 10 inhabitants per km2 (1 point).

- -

- The site is located in a municipality with a development level above the national average (4 points);

- -

- The site is located in a municipality with a development level ranging from 80% to 100% of the national average (3 points);

- -

- The site is located in a municipality with a development level ranging from 60% to 80% of the national average (2 points);

- -

- The site is located in a municipality with a development level below 60% of the national average (1 point).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PTU | Potential Tourist Use |

| DR | Degradation Risk |

| EEA | European Environment Agency |

| ES | Ecosystem Services |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| NP | Nature Park |

| COP | Conference of the Parties |

References

- Zolfani, S.H.; Sedaghat, M.; Maknoon, R.; Zavadskas, E.K. Sustainable tourism: A comprehensive literature review on frameworks and applications. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2015, 28, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Guilarte, Y.; Lois González, R.C. Sustainability and visitor management in tourist historic cities: The case of Santiago de Compostela, Spain. J. Herit. Tour. 2018, 13, 489–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Consumption and Production. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-consumption-production/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- United Nations Statistics Division. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2025. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2025 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Khan, M.R.; Khan, H.U.R.; Lim, C.K.; Tan, K.L.; Ahmed, M.F. Sustainable tourism policy, destination management and sustainable tourism development: A moderated-mediation model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.F.; Khalid Balisany, W.M. Sustainable tourism management and ecotourism as a tool to evaluate tourism’s contribution to the sustainable development goals and local community. OTS Can. J. 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Fang, P.; Wan, A.; Lee, S.; Li, Y.; Song, W. Revisiting sustainable tourism: A bibliometric review of key contributors and themes with an integrated framework. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2025, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GhulamRabbany, M.; Afrin, S.; Rahman, A.; Islam, F.; Hoque, F. Environmental effects of tourism. Am. J. Environ. Energy Power Res. 2013, 1, 117–130. [Google Scholar]

- Baloch, Q.B.; Shah, S.N.; Iqbal, N.; Sheeraz, M.; Asadullah, M.; Mahar, S.; Khan, A.U. Impact of tourism development upon environmental sustainability: A suggested framework for sustainable ecotourism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 5917–5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Forests, Desertification and Biodiversity. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/biodiversity/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Kim, K.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. How does tourism in a community impact the quality of life of community residents? Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H. Influence analysis of community resident support for sustainable tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleshinloye, K.D.; Woosnam, K.M.; Tasci, A.D.; Ramkissoon, H. Antecedents and outcomes of resident empowerment through tourism. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 656–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Valentine, K.M.; Knopf, R.C.; Vogt, C.A. Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 1056–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H. Perceived social impacts of tourism and quality-of-life: A new conceptual model. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 442–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumede, T.K.; Nzama, A.T.; Mdiniso, J.M. Evaluating the effectiveness of the strategies for sustaining nature-based tourism amid global health crises: A global perspective. In Sustaining Nature-Based Tourism Amid Global Crises; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbnb.coop. Sustainable Tourism: A Guide for Travellers [Blog Post]. Available online: https://fairbnb.coop/blog/sustainable-tourism/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Boo, E. Ecotourism: The Potentials and Pitfalls; World Wildlife Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 1990; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg, K.; McCool, S.F. A critique of environmental carrying capacity as a means of managing the effects of tourism development. Environ. Conserv. 1998, 25, 291–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeton, S. Ecotourism: A Practical Guide for Rural Communities; Landlinks Press: Collingwood, Australia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Çetinkaya, C.; Kabak, M.; Erbaş, M.; Özceylan, E. Evaluation of ecotourism sites: A GIS-based multi-criteria decision analysis. Kybernetes 2018, 47, 1664–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Goal 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth. United Nations—Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/economic-growth/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Budiasa, I.W.; Ambarawati, I.G.A.A. Community-based agro-tourism as an innovative integrated farming system development model towards sustainable agriculture and tourism in Bali. J. Agric. Rural Dev. 2014, 4, 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Susila, I.; Dean, D.; Harismah, K.; Priyono, K.D.; Setyawan, A.A.; Maulana, H. Does interconnectivity matter? An integration model of agro-tourism development. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2024, 29, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, M.; Agius, K.; Allen, M.E.; Ariya, G.; Blanco-Gregory, R.; Boyle, C.; Conti, E. Managing visitor experiences in nature based tourism. In Managing Visitor Experiences in Nature-Based Tourism; Albrecht, J.N., Ed.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2021; p. 695. [Google Scholar]

- Bichler, B.F.; Peters, M. Soft adventure motivation: An exploratory study of hiking tourism. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korir, J.; Muchiri, J.; Kamwea, J. Wildlife-based tourism, ecology and sustainability of protected areas in Kenya. J. Nat. Sci. Res. 2013, 3, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, P.W.; Fleming, P.A. Are negative effects of tourist activities on wildlife over-reported? A review of assessment methods and empirical results. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 211, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, D.; Upadhyay, V.; Puri, B. Tourism at protected areas: Sustainability or policy crunch? IIM Kozhikode Soc. Manag. Rev. 2018, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Gao, Y.; Sun, J. The impact of geographical location of households’ residences on the livelihoods of households surrounding protected areas: An empirical analysis of seven nature reserves across three provinces in China. Land 2025, 14, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brilha, J. Inventory and Quantitative Assessment of Geosites and Geodiversity Sites: A Review. Geoheritage 2016, 8, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brilha, J.; Gray, M.; Pereira, P. Geodiversity: An Integrative Review as a Contribution to the Sustainable Management of the Whole of Nature. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 89, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, M. Geodiversity: The backbone of geoheritage and geoconservation. In Geoheritage; Reynard, E., Brilha, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, S.; Kumar, P.; Chauhan, G.; Thakkar, M.G. Conservation and sustainable development of geoheritage, geopark, and geotourism: A case study of Cenozoic successions of Western Kutch, India. Geoheritage 2019, 11, 1475–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibanez, J.J.; Brevik, E.C. Divergence in natural diversity studies: The need to standardize methods and goals. Catena 2019, 182, 104110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, A.S.; Carević, I.; Trnavac Bogdanović, D.; Langović, M.; Batoćanin, N.; Petronijević, J. Geotourism based on geoheritage as a basis for the sustainable development of the Golija Nature Park, Southwest Serbia. Land 2025, 14, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksova, B.; Milevski, I.; Lukić, T.; Marković, S.B.; Manevska, I. Preliminary evaluation of geosites for nature-based tourism in Mavrovo and Šar Planina National Parks, North Macedonia. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks 2025, 13, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, J.; Pavlović, M. Geografske Regije Jugoslavije (Srbija i Crna Gora); Savremena Administracija: Beograd, Serbia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gajić, M. Flora i Vegetacija Golije i Javora; Šumarski Fakultet: Ivanjica, Serbia, 1989; p. 592. [Google Scholar]

- CEP. Prostorni Plan Područja Posebne Namene Parka Prirode “Golija”, Predlog Plana, Radna Verzija; Centar za Planiranje Urbanog Razvoja: Beograd, Serbia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Haartsen, T.; Gieling, J. Dealing with the loss of the village supermarket: The perceived effects two years after closure. Sociol. Rural. 2021, 61, 561–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomić, N.; Stojsavljević, R. Spatial Planning and Sustainable Tourism—A Case Study of Golija Mountain (Serbia). Eur. Res. 2013, 65, 2918–2929. [Google Scholar]

- Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia 31/2012-3. Decree on Protection Regimes. 2012. Available online: https://www.pravno-informacioni-sistem.rs/SlGlasnikPortal/eli/rep/sgrs/vlada/uredba/2012/31/1 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia 47/2009-3. Decree on the Protection of the Nature Park Golija. 2009. Available online: https://www.pravno-informacioni-sistem.rs/SlGlasnikPortal/eli/rep/sgrs/vlada/uredba/2009/47/2 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia 16/2009-21. Decree on the Determination of the Spatial Plan of the Special Purpose Area of the Nature Park Golija. 2009. Available online: https://www.pravno-informacioni-sistem.rs/SlGlasnikPortal/eli/rep/sgrs/vlada/uredba/2009/16/7/reg (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- UNESCO. International Coordinating Council of the Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Programme: Designation of the Golija–Studenica Biosphere Reserve; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2001; Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/mab/golija-studenica (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Miljanović, D. Golija—Studenica: Geographical Basis of Sustainable Development of the Biosphere Reserve; Institute of Geography, University of Belgrade: Belgrade, Serbia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, I.D.; Croft, D.B.; Green, R. Nature Conservation and Nature-Based Tourism: A Paradox? Environments 2019, 6, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Studenica Monastery—World Heritage List. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/389/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- UNESCO. Stari Ras and Sopoćani—World Heritage List. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/96/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Nature Park Golija Management Plan for the Period 2021–2030 (2020). Available online: https://srbijasume.rs/ssume/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/PlanUpravGolija.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Lima, F.F.; Brilha, J.; Salamuni, E. Inventorying geological heritage in large territories: A methodological proposal applied to Brazil. Geoheritage 2010, 2, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guju, M.; Mureșan, A.; Doboș, R.; Petrea, D.; Nedelea, A. Evaluating geosites and developing geotourism in the Țara Hațegului region, Romania. Geoheritage 2025, 17, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes-Gutiérrez, I.; Fernández-Martínez, E. Geosites inventory in the Leon Province (Northwestern Spain): A tool to introduce geoheritage into regional environmental management. Geoheritage 2010, 2, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes-Gutiérrez, I.; Fernández-Martínez, E. Mapping geosites for geoheritage management: A methodological proposal for the regional park of Picos de Europa (León, Spain). Environ. Manag. 2012, 50, 789–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cendrero, A. The role of geoscientists in environmental management. Episodes 1996, 19, 82–84. [Google Scholar]

- Carcavilla, L.; López-Martínez, J.; Durán, J.J. Patrimonio Geológico y Geodiversidad: Investigación, Conservación, Gestión y Relación con los Espacios Naturales Protegidos; Instituto Geológico y Minero de España (IGME): Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Reynard, E.; Fontana, G.; Kozlik, L.; Scapozza, C. A method for assessing “scientific” and “additional values” of geomorphosites. Geogr. Helv. 2007, 62, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cortés, A.; Carcavilla Urquí, L. Documentación del Patrimonio Geológico Español: Propuesta de ficha y base de datos para su inventario nacional; Instituto Geológico y Minero de España (IGME): Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, P.; Pereira, D. Methodological guidelines for geomorphosite assessment. Geogr. Fis. Din. Quat. 2010, 33, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassoulas, C.; Mouriki, D.; Dandoulaki, M.; Mountrakis, D. Quantitative assessment of geosites as an effective tool for geoheritage management. Geoheritage 2012, 4, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maczka, K.; Matczak, P.; Jeran, A.; Chmielewski, P.J. Conflicts in ecosystem services management: Analysis of stakeholder participation in Natura 2000 in Poland. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 117, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagles, P.E.J.; McCool, S.F. Tourism in National Parks and Protected Areas: Planning and Management; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. Guidelines for Protected Area Management Categories; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland; Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Ispod Jankovog Kamen | The site is located north of Golija’s highest peak (1833 m), in the settlement of Dajići (Municipality of Ivanjica), covering an area of 60.80 ha. It consists of a diverse and rich forest community. |

| 2. | Pašina Česma | The site is located below Bojevo Brdo (1700 m), in the settlement of Medovine (Municipality of Ivanjica), covering an area of 40.69 ha. It consists of two springs situated 400 m apart. |

| 3. | Karalići | The site is located in the spring area of the Galunjin Potok stream in the settlement of Dajići (Municipality of Ivanjica), covering an area of 34 ha. It consists of a specific forest community of beech, spruce, fir, and Heldreich’s maple (Acer heldreichii). |

| 4. | Vodica | The site is located in the settlement of Dajići (Municipality of Ivanjica), covering an area of 67.96 ha. It consists of a specific forest community. |

| 5. | Tresava (Bele Vode) | The site is located within the settlement of Dajići (Municipality of Ivanjica), covering an area of 15.20 ha. It consists of characteristic peat bog vegetation. |

| 6. | Dajićko Lake | The site is located in the settlement of Gleđica (Municipality of Ivanjica), at an elevation of 1436 m, covering an area of 39.92 ha. It is fed by atmospheric precipitation and nearby springs and serves as a habitat for the crested newt (Triturus cristatus). |

| 7. | Palež | The site is located on the Dajić Mountains, in the settlement of Kumanica (Municipality of Ivanjica), at an elevation of 1250 m, covering an area of 39.92 ha. It consists of a beech forest community that includes the protected holly (Ilex aquifolium), a Tertiary relict in this region. |

| 8. | Isposnice | The site is located near the medieval Studenica Monastery, in the settlement of Savovo (City of Kraljevo), covering an area of 20.50 ha. It is characterized by a relict forest community with a unique structure and composition. The community contains over 20 woody species, primarily various species of oak, hornbeam, maple, ash, walnut, linden, and others. |

| 9. | Košanin’s Lakes | The site is located in the settlement of Vrmbaje (Municipality of Ivanjica), covering an area of 50.12 ha. It consists of the Great and Small Lakes. The Great Lake is overgrown with dense vegetation of beech, spruce, and fir, while the water area of the Small Lake has not yet become overgrown. |

| 10. | Crepuljnik | The site is located in the settlement of Vrmbaje (Municipality of Ivanjica), covering an area of 65.80 ha. It comprises six species within the forest community. The community is of a mosaic type and is formed by beech, maple, spruce, fir, mountain maple, and mountain elm. |

| 11. | Radočelo | The site is located in the settlement of Bzovik (City of Kraljevo), covering an area of 44 ha. Three forest communities are clearly expressed: beech and fir; beech, fir, and spruce; and Scots pine, beech, and black pine. |

| 12. | Izubra | The site is located in the settlements of Koritnik and Čečina (Municipality of Ivanjica), covering an area of 66.10 ha. It encompasses the lower course of the Izubra River (a right tributary of the Studenica). The river course features two series of waterfalls, the largest of which is 7 m high. The forest community consists of beech forests, beech–hornbeam forests, and beech–spruce forests. |

| 13. | Plakaonica | The site is located in the settlement of Biniće (Municipality of Raška), covering an area of 24.80 ha. It consists of a forest community of varying ages, including mature beech and Scots pine forest as well as artificially planted Scots pine forest. The site is of high scientific importance and is used in practice, particularly in forestry science. |

| 14. | Ravnine | The site is located in the settlement of Plešin (Municipality of Raška), covering an area of 32.40 ha. It comprises three distinct forest communities: pure beech, pure spruce, and a spruce–beech mixture. |

| 15. | Iznad Ljutih Livada | The site is located within the settlement of Koritnik (Municipality of Ivanjica), covering an area of 27.60 ha. It is the oldest protected site (since 1950) on Mount Golija and represents a natural rarity in Europe. The forest community consists of a tridominant spruce–fir–beech forest (Piceo–Abieti–Fagetum). These primeval-type forests are well preserved and among the oldest remaining in the region. Fir trees reach heights of 55 m, spruce 54 m, and beech 43 m. |

| 16. | Crna Reka | The site is located in the settlement of Koritnik (Municipality of Ivanjica), covering an area of 28.80 ha. It comprises the headwaters of the Studenica River, along with its canyon and characteristic rocky vegetation. |

| 17. | Radulovac | The site is located in the settlement of Koritnik (Municipality of Ivanjica), covering an area of 4 ha. It consists of one of the springs of the Crna Reka—Cikotina Voda—and also includes a secondary natural pasture. |

| 18. | Crna Reka Spring | The site is located in Odvraćenica, in the settlement of Koritnik (Municipality of Ivanjica), covering an area of 0.20 ha. It consists of the second spring of the Crna Reka, which comprises two sources. This is the smallest site within the first-degree protection regime. |

| Criterion/Indicator | Parameter | Points | Weight (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Vulnerability | The site’s elements are not susceptible to damage caused by anthropogenic activities. | 4 | 10 |

| Secondary elements may be susceptible to damage as a result of anthropogenic activity. | 3 | ||

| The main elements may be susceptible to damage as a result of anthropogenic activity. | 2 | ||

| All elements are potentially susceptible to damage resulting from anthropogenic activity. | 1 | ||

| B. Accessibility | The site is located less than 100 m from an asphalt road and has parking facilities for buses. | 4 | 10 |

| The site is located less than 500 m from an asphalt road. | 3 | ||

| The site is accessible by bus via a gravel road. | 2 | ||

| The site has no direct road access but is located less than 1 km from a road accessible by bus. | 1 | ||

| C. Usage restrictions | The site has no usage restrictions for students and tourists. | 4 | 5 |

| The site may be used by students and tourists, but only occasionally. | 3 | ||

| The site can be used only after overcoming certain limitations (legal, permit-related, physical barriers, floods, etc.). | 2 | ||

| The use of the site by students and tourists is severely constrained due to hardly surmountable limitations (legal, permit-related, physical barriers, floods, etc.). | 1 | ||

| D. Safety | The site has safety installations (fences, stairs, handrails, etc.), mobile phone coverage, and is located less than 5 km from emergency services. | 4 | 10 |

| The site has safety installations, mobile phone coverage, and is located less than 25 km from emergency services. | 3 | ||

| The site lacks safety installations but has mobile phone coverage and is located less than 50 km from emergency services. | 2 | ||

| The site lacks safety installations, has no mobile phone coverage, and is located more than 50 km from emergency services. | 1 | ||

| E. Logistics | Accommodation and restaurants for groups of 50 people are located less than 15 km from the site. | 4 | 5 |

| Accommodation and restaurants for groups of 50 people are located less than 50 km from the site. | 3 | ||

| Accommodation and restaurants for groups of 50 people are located less than 100 km from the site. | 2 | ||

| Accommodation and restaurants for groups of fewer than 25 people are located less than 50 km from the site. | 1 | ||

| F. Population density | The site is located in a municipality with a population density of more than 100 inhabitants per km2. | 4 | 5 |

| The site is located in a municipality with a population density of 25–100 inhabitants per km2. | 3 | ||

| The site is located in a municipality with a population density of 10–25 inhabitants per km2. | 2 | ||

| The site is located in a municipality with a population density of fewer than 10 inhabitants per km2. | 1 | ||

| G. Proximity to other values | Several cultural values are located less than 5 km from the site. | 4 | 5 |

| Several cultural values are located less than 10 km from the site. | 3 | ||

| One cultural and one ecological value are located less than 10 km from the site. | 2 | ||

| One cultural value is located less than 10 km from the site. | 1 | ||

| H. Landscape | The site is currently promoted as a tourist destination in national promotional campaigns. | 4 | 15 |

| The site is occasionally promoted as a tourist destination in national promotional campaigns. | 3 | ||

| The site is currently promoted as a tourist destination in local promotional campaigns. | 2 | ||

| The site is occasionally promoted as a tourist destination in local promotional campaigns. | 1 | ||

| I. Uniqueness | The site displays unique and uncommon features in the context of this and neighboring countries. | 4 | 10 |

| The site displays unique and uncommon features at the national level. | 3 | ||

| The site displays features that are common within this region but uncommon in other parts of the country. | 2 | ||

| The site displays features that are fairly common throughout the country. | 1 | ||

| J. Observation Conditions | All elements of the site are clearly visible under good conditions. | 4 | 5 |

| There are some obstacles that make it difficult to observe certain elements of the site. | 3 | ||

| There are obstacles that hinder the observation of the main elements of the site. | 2 | ||

| There are obstacles that almost completely prevent the observation of the main elements of the site. | 1 | ||

| K. Interpretative potential | The site presents all elements in a very clear and striking way, easily understandable to all types of visitors. | 4 | 10 |

| Visitors need to have some prior knowledge to understand all elements of the site. | 3 | ||

| Visitors need to have a solid level of prior knowledge to understand all elements of the site. | 2 | ||

| The site presents elements that are understandable only to specialists in physical geography (geology, geomorphology, hydrology, or biogeography). | 1 | ||

| L. Economic development level | The site is located in a municipality with a development level above the national average. | 4 | 5 |

| The site is located in a municipality with a development level ranging from 80% to 100% of the national average. | 3 | ||

| The site is located in a municipality with a development level ranging from 60% to 80% of the national average. | 2 | ||

| The site is located in a municipality with a development level below 60% of the national average. | 1 | ||

| M. Proximity to Recreational Areas | The site is located less than 5 km from a recreational area or tourist attraction. | 4 | 5 |

| The site is located less than 10 km from a recreational area or tourist attraction. | 3 | ||

| The site is located less than 15 km from a recreational area or tourist attraction. | 2 | ||

| The site is located less than 20 km from a recreational area or tourist attraction. | 1 | ||

| Total | 100 |

| Criteria/Indicator | Parameter | Score |

|---|---|---|

| A. Susceptibility to damage | All elements are potentially subject to damage. | 4 |

| The main elements are potentially subject to damage. | 3 | |

| The secondary elements are potentially subject to damage. | 2 | |

| The secondary elements are only slightly susceptible to damage. | 1 | |

| B. Proximity to areas/activities that may cause degradation | The site is located less than 50 m from a potentially harmful area/activity. | 4 |

| The site is located less than 200 m from a potentially harmful area/activity. | 3 | |

| The site is located less than 500 m from a potentially harmful area/activity. | 2 | |

| The site is located less than 1 km from a potentially harmful area/activity. | 1 | |

| C. Legal protection | The site is located in an area without legal protection and without access control. | 4 |

| The site is located in an area without legal protection, but with access control. | 3 | |

| The site is located within a protected area, but without access control. | 2 | |

| The site is located within a protected area with access control. | 1 | |

| D. Accessibility | The site is located less than 100 m from a paved road and has parking for buses. | 4 |

| The site is located less than 500 m from a paved road. | 3 | |

| The site is accessible by bus via a gravel road. | 2 | |

| The site has no direct road access but is located less than 1 km from a road accessible by bus. | 1 | |

| E. Population density | The site is located in a municipality with a population density of more than 100 inhabitants per km2. | 4 |

| The site is located in a municipality with a population density of 25–100 inhabitants per km2. | 3 | |

| The site is located in a municipality with a population density of 10–25 inhabitants per km2. | 2 | |

| The site is located in a municipality with a population density of fewer than 10 inhabitants per km2. | 1 |

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | Total Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 250 |

| 2 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 220 |

| 3 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 220 |

| 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 205 |

| 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 275 |

| 6 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 280 |

| 7 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 225 |

| 8 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 265 |

| 9 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 205 |

| 10 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 180 |

| 11 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 200 |

| 12 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 265 |

| 13 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 230 |

| 14 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 220 |

| 15 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 265 |

| 16 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 225 |

| 17 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 235 |

| 18 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 245 |

| A | B | C | D | E | Total Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 185 |

| 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 135 |

| 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 115 |

| 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 185 |

| 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 115 |

| 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 220 |

| 7 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 185 |

| 8 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 210 |

| 9 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 240 |

| 10 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 135 |

| 11 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 140 |

| 12 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 150 |

| 13 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 170 |

| 14 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 115 |

| 15 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 115 |

| 16 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 115 |

| 17 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 115 |

| 18 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 220 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Petrović, D.; Mihajlović, L.; Vukoičić, D.; Milinčić, M.; Ristić, D. Sustainable Development and Evaluation of Natural Heritage in Protected Areas: The Case of Golija Nature Park, Serbia. Earth 2025, 6, 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth6040153

Petrović D, Mihajlović L, Vukoičić D, Milinčić M, Ristić D. Sustainable Development and Evaluation of Natural Heritage in Protected Areas: The Case of Golija Nature Park, Serbia. Earth. 2025; 6(4):153. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth6040153

Chicago/Turabian StylePetrović, Dragan, Ljiljana Mihajlović, Danijela Vukoičić, Miroljub Milinčić, and Dušan Ristić. 2025. "Sustainable Development and Evaluation of Natural Heritage in Protected Areas: The Case of Golija Nature Park, Serbia" Earth 6, no. 4: 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth6040153

APA StylePetrović, D., Mihajlović, L., Vukoičić, D., Milinčić, M., & Ristić, D. (2025). Sustainable Development and Evaluation of Natural Heritage in Protected Areas: The Case of Golija Nature Park, Serbia. Earth, 6(4), 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth6040153