Spatial and Temporal Changes in Suspended Sediment Load and Their Contributing Factors in the Upper Reaches of the Yangtze River

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area, Dataset and Methods

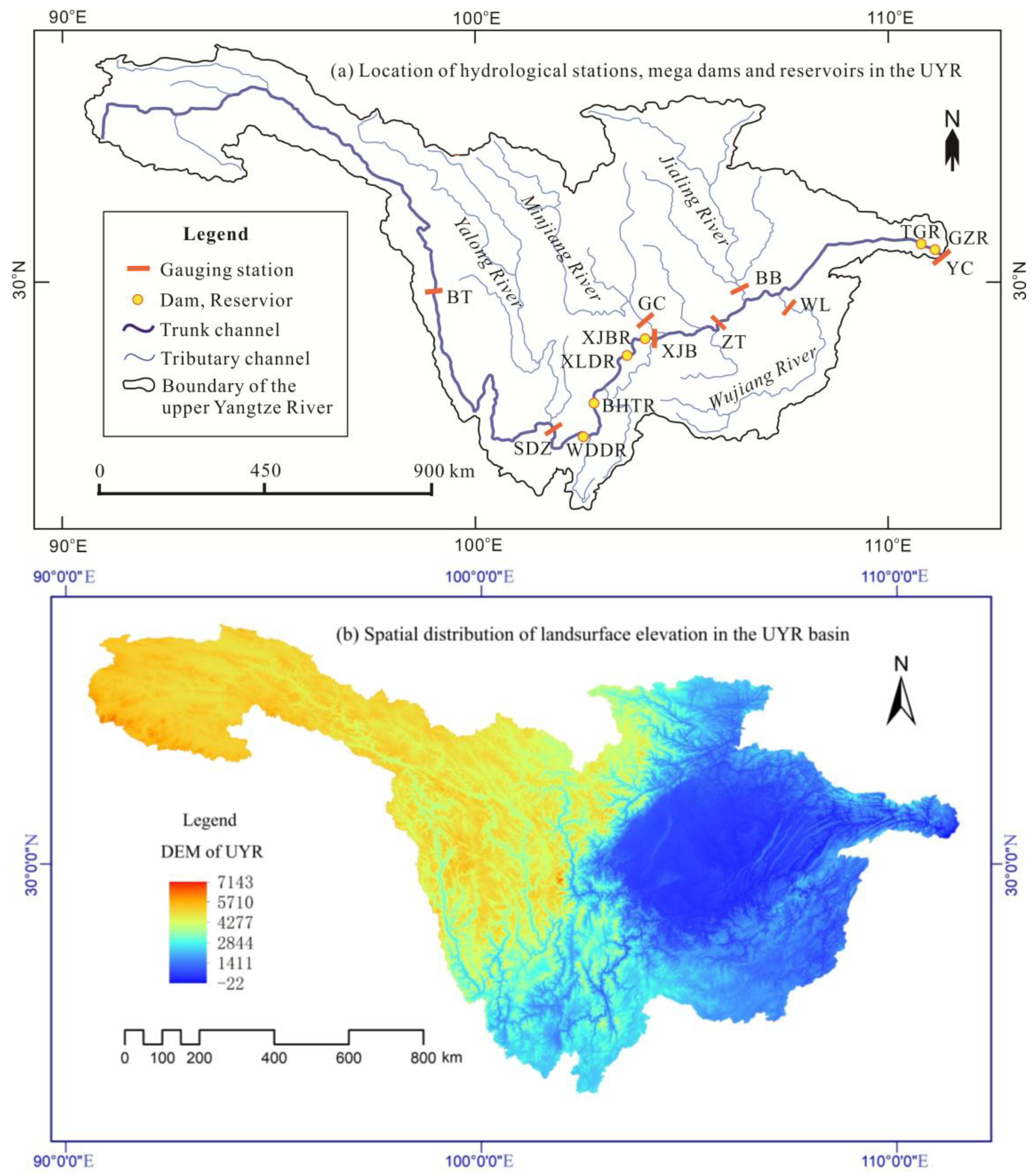

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Dataset

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Methods for Identifying Inflection Points in Data Time Series

2.3.2. Methods for Calculating Potential ET

- E0 refers to the daily potential ET (unit: mm);

- G denotes the soil heat flux density (unit: MJ·m−2·d−1);

- T represents the daily average air temperature at a height of 2 m (unit: °C);

- u2 is the wind speed at a height of 2 m (unit: m·s−1);

- es stands for the mean saturation vapor pressure (unit: kPa);

- eais the actual vapor pressure (unit: kPa);

- ∆ indicates the slope of the saturation vapor pressure curve (unit: kPa·°C−1);

- γ denotes the psychrometric constant (unit: kPa·℃−1);

- Rn represents the net radiation at the land surface (unit: MJ·m−2·d−1).

2.3.3. Calculation Method for Contribution Ratio of Dominant Factors

3. Results

3.1. The Change Trend of Suspended Sediment Load

3.1.1. Changes in SSL at the Hydrological Stations

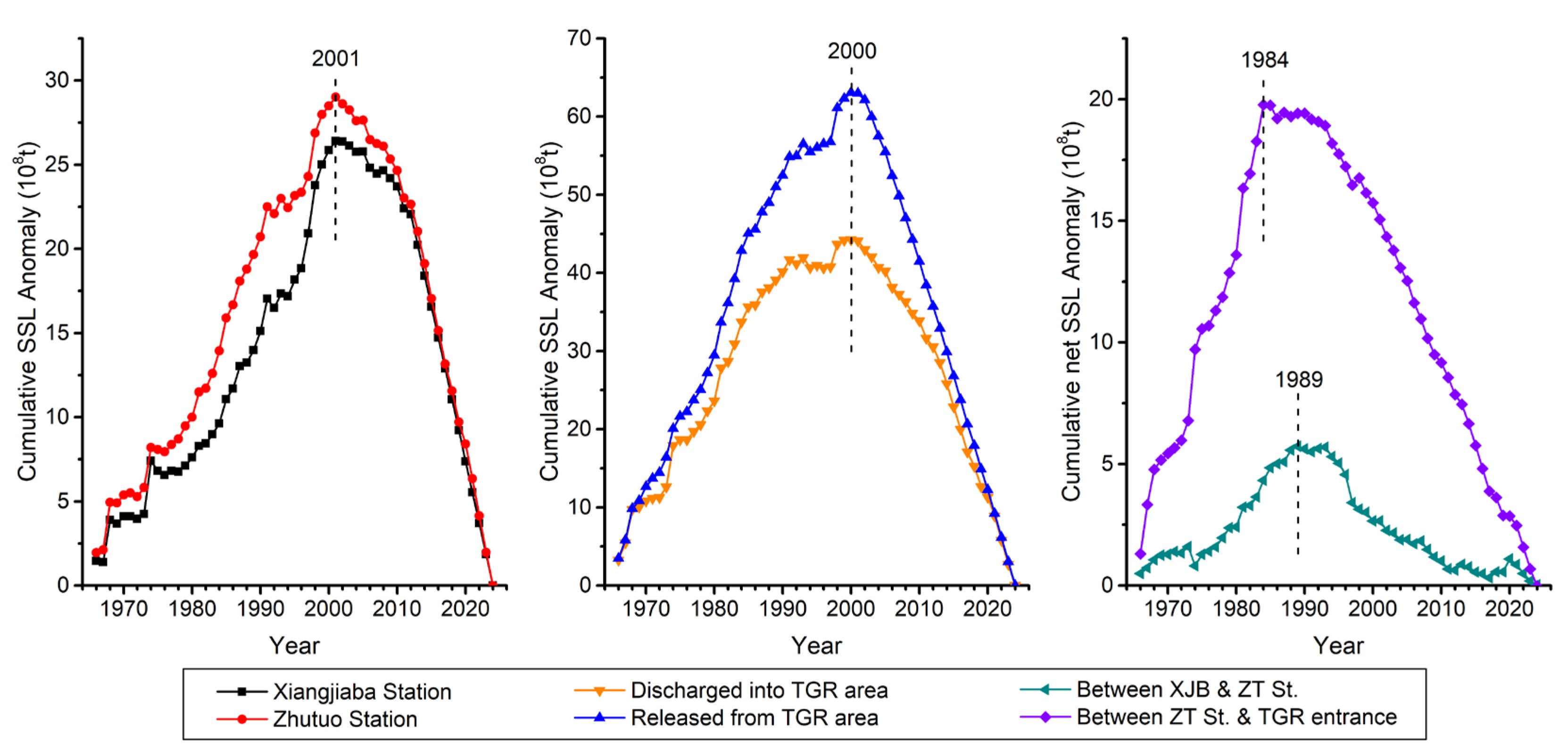

3.1.2. Changes in Net SSL in Typical River Sections

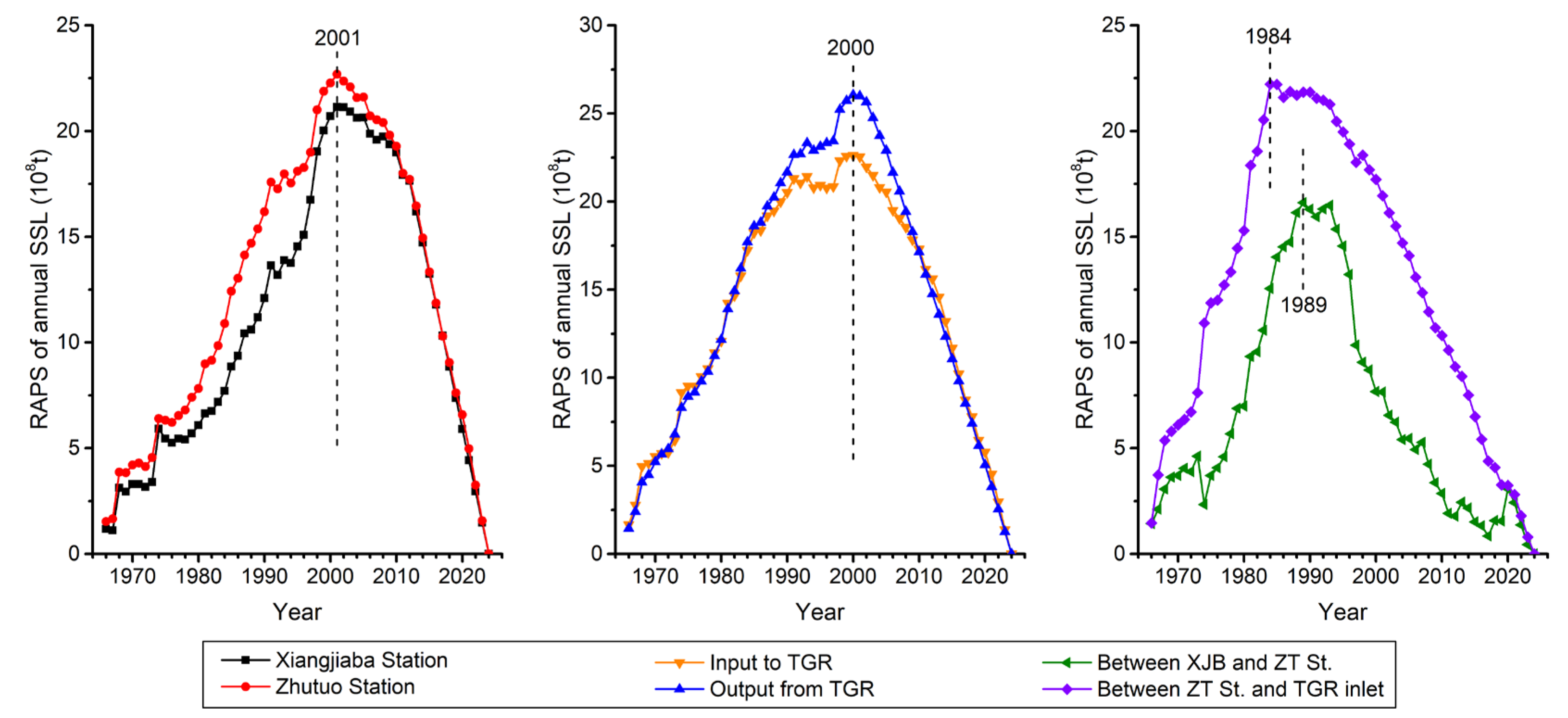

3.2. Identification of Inflection Years and Division of Stages

3.2.1. Inflection Years Based on Change in a Single Series of SSL

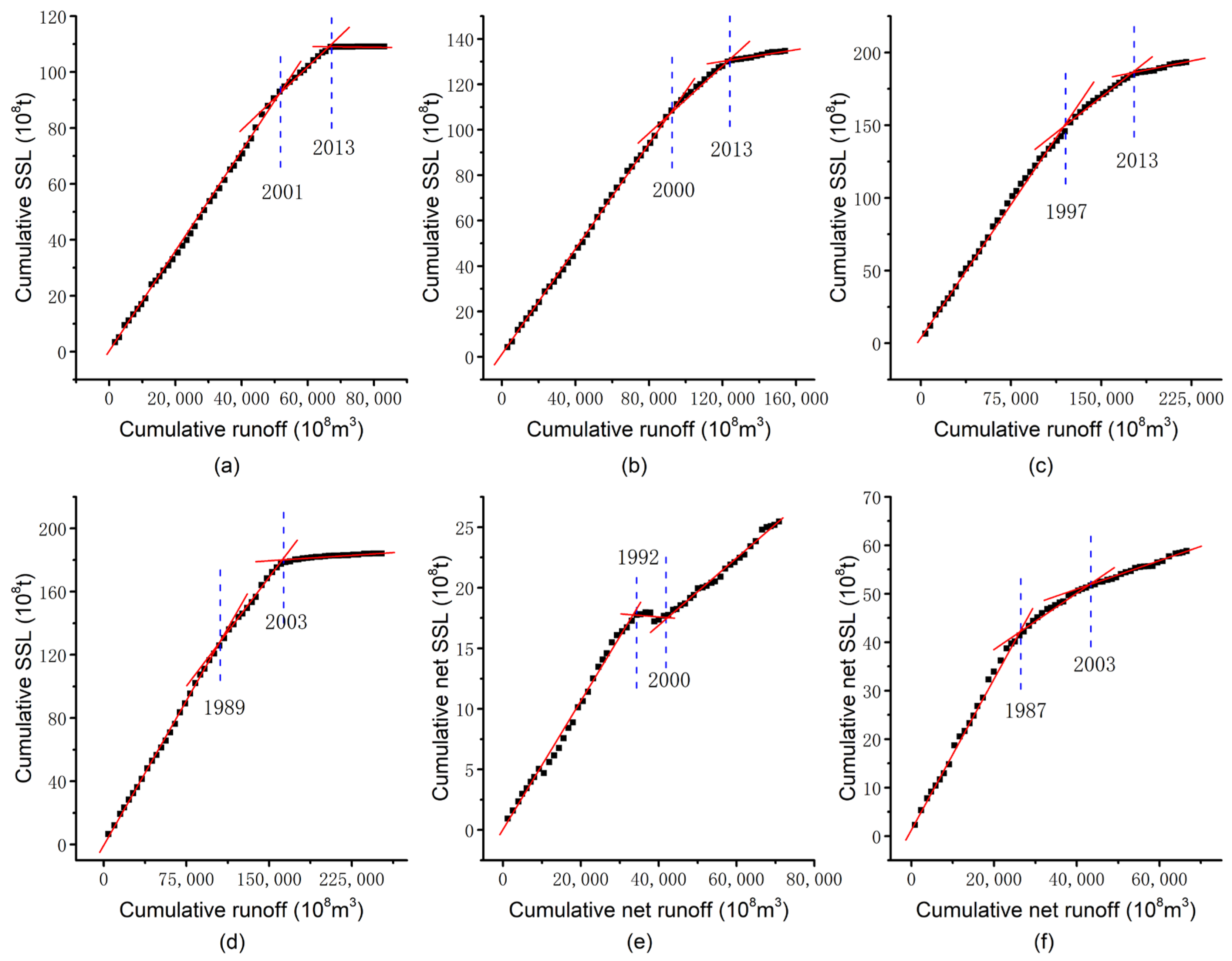

3.2.2. Inflection Years Based on Change in Double Series of Runoff and SSL

3.3. Slope Change Ratio of Cumulative SSL in Variation Stages

3.3.1. Relationships Between the Year and Cumulative SSL

3.3.2. Change Ratio of Cumulative SSL

3.4. Contributions of Climate and Human Activities

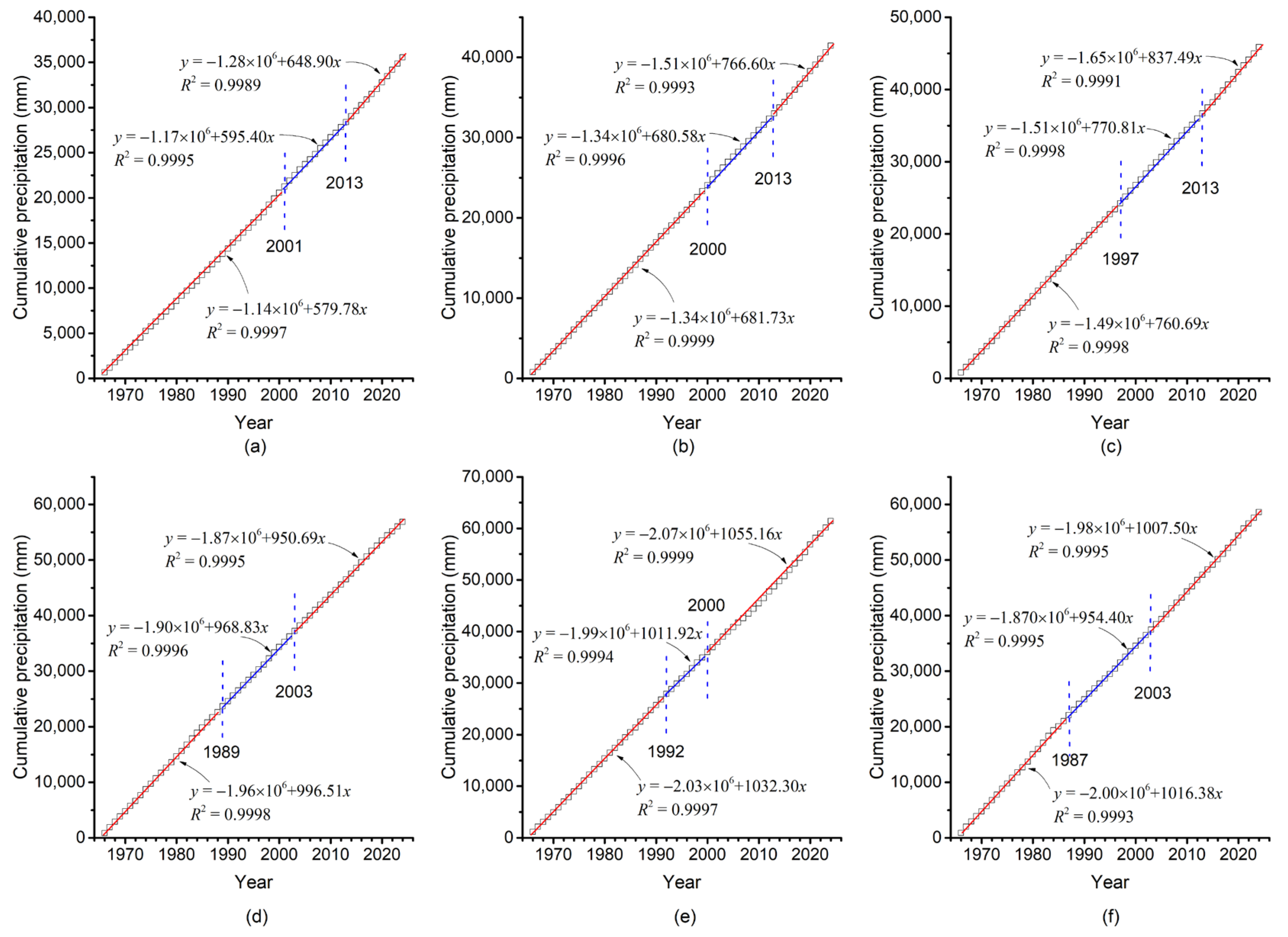

3.4.1. Change Ratio of Cumulative Precipitation

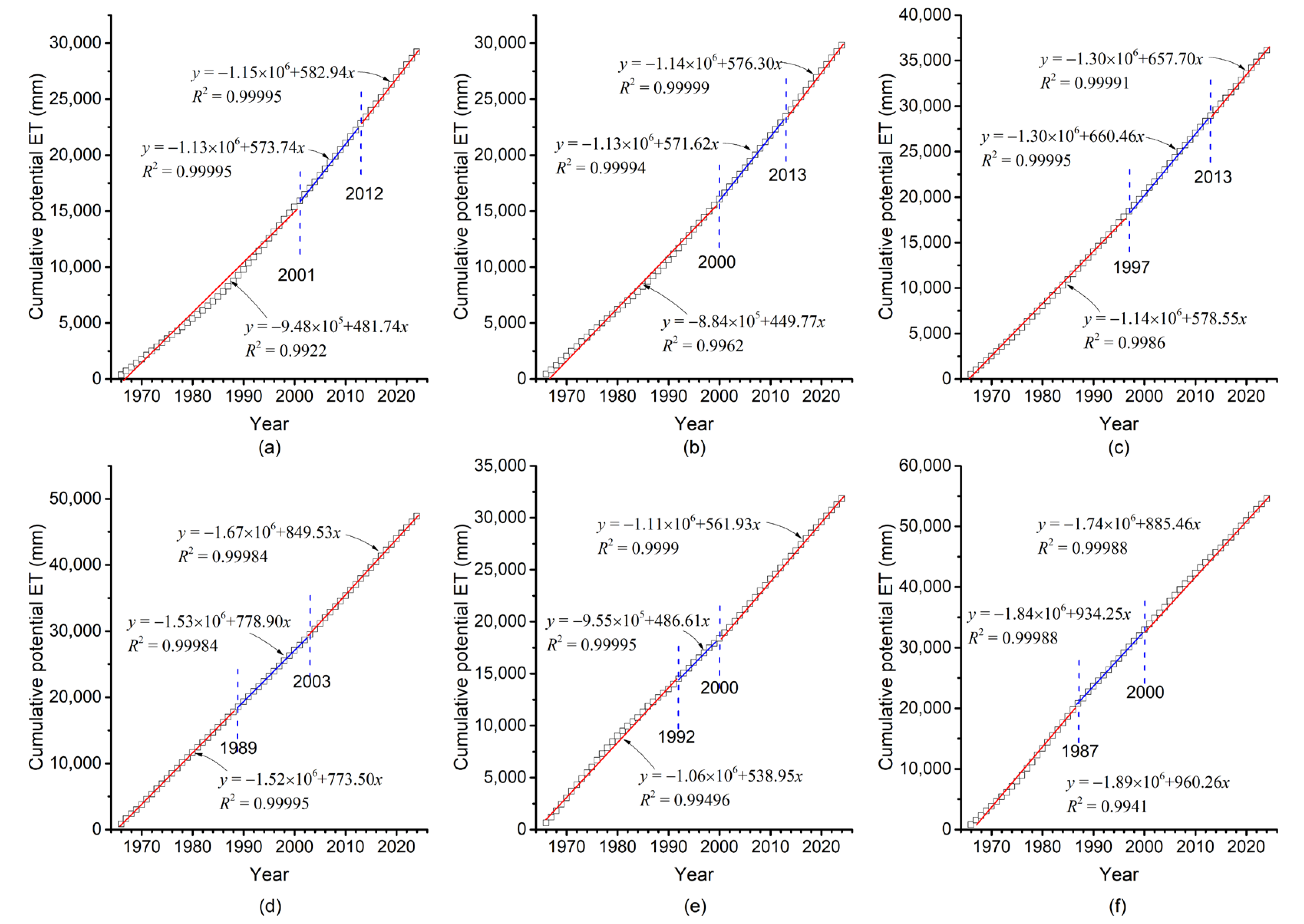

3.4.2. Change Ratio of Cumulative Potential ET

3.4.3. Relative Contribution Ratios of Climate and Human Activities

4. Discussion

4.1. The Universality of the Sharp Reduction in SSL in the Study Area

4.2. The Necessity of Stage Division for SSL Changes

4.3. The Reliability of Calculated Relative Contribution Ratios

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The sediment quantity variation trends in the basin above XJB Station, the basin above Zhutuo Station, and the inflow and outflow of the Three Gorges Reservoir are similar, with their mutation years being 2001, 2000, 1997, and 1989, respectively. The mutation years of sediment transport in the two intervals (XJB to Zhutuo Station, and Zhutuo to Yichang Station) are 1992 and 1984, respectively. The period before the first mutation year is designated as the baseline period, and the period after is defined as the variation period; the variation period is further divided into Variation Period I and Variation Period II using mutation years such as 2013, 2003, and 2000 as boundaries.

- (2)

- Compared with the baseline period, the slopes of cumulative sediment transport in the 6 river reaches/basins of the study area have all decreased significantly. Their variation rates range from −0.225 to −1.018 in Variation Period I and from −0.490 to −0.995 in Variation Period II. This indicates that sediment transport has experienced two sudden reductions; meanwhile, the reduction rate of cumulative sediment transport in each river reach has increased sequentially in the two variation periods.

- (3)

- The contribution rate of human activities to the reduction in sediment transport in different reaches of the upper Yangtze River ranges from 87.5% to 111.9%, the contribution rate of precipitation variation ranges from −14.3% to 12.4%, and the contribution rate of evapotranspiration variation ranges from −0.1% to 0.6%. For the entire upper Yangtze River basin, the contribution rates of human activities to the reduction in sediment transport are 87.5% in Variation Period I and 95.1% in Variation Period II, while the contribution rates of climate change are 12.4% and 4.9%, respectively. Human activities play an absolutely dominant role in the reduction of sediment transport in the study area.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qian, N.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, Z. Channel Processes; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1987. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Wang, X. Changes of water and sediment processes in the Yellow River and their responses to ecological protection during the last six decades. Water 2023, 15, 2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Ni, J.; Borthwick, A.G.L.; Yang, L. A preliminary estimate of human and natural contributions to the changes in water discharge and sediment load in the Yellow River. Glob. Planet. Change 2011, 76, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yan, M.; Yan, Y.X.; Shi, C.; He, L. Contributions of climate change and human activities to the changes in runoff increment in different sections of the Yellow River. Quat. Int. 2012, 282, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.L.; Zhao, Q.Y.; Belkin, I.M. Temporal variation in the sediment load of the Yangtze River and the influences of the human activities. J. Hydrol. 2002, 263, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, C.; Reidy, C.A.; Dynesius, M.; Revenga, C. Fragmentation and flow regulation of the world’s large river systems. Science 2005, 308, 405–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syvitski, J.P.M.; Voromarty, C.J.; Kettner, A.J.; Green, P. Impact of humans on the flux of terrestrial sediment to the global coastal ocean. Science 2005, 308, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, W.L. Downstream hydrologic and geomorphic effects of large dams on American rivers. Geomorphology 2006, 79, 336–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Ran, L.; Su, T. Climatic and anthropogenic impacts on runoff changes in the Songhua River basin over the last 56 years (1955–2010), Northeastern China. Catena 2015, 127, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.K.; Rhoads, B.L.; Wang, D.; Wu, J.C.; Zhang, X. Impacts of large dams on the complexity of suspended sediment dynamics in the Yangtze River. J. Hydrol. 2018, 558, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.B.; Wen, A.B. Variations of sediment in upper stream of Yangtze River and its tributary. Shuilixuebao 2002, 33, 56–59. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Zou, X.; Liu, Q.; Yao, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, X.; Wang, C.; Yu, W.; Wang, T. Assessing natural and anthropogenic influences on water discharge and sediment load in the Yangtze River, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 607–608, 920–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yu, M.; Lu, G.; Cai, T.; Xia, Z.; Ren, L. Impacts of the Gezhouba and Three Gorges reservoirs on the sediment regime in the Yangtze River, China. J. Hydrol. 2011, 403, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walling, D.E. Human impact on land–ocean sediment transfer by the world’s rivers. Geomorphology 2006, 79, 192–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.B.; Lu, X.X. Sediment load change in the Yangtze River (Changjiang): A review. Geomorphology 2014, 215, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wang, G.; Sun, S.; Chen, S.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y.; Sun, H.; Song, C.; Lin, S.; Hu, Z. Asynchronous changes and driving mechanisms of water-sediment transport in the Jinsha River Basin: Response to climate change and human activities. Catena 2025, 259, 109325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Shi, C.X.; Zhang, S.H.; Zhang, L. Impact of human activities on recent changes in sediment discharge of the upper Yangtze River. Prog. Geogr. 2010, 29, 15–22. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.L.; Xu, K.H.; Milliman, J.D.; Yang, H.F.; Wu, C.S. Decline of Yangtze River water and sediment discharge: Impact from natural and anthropogenic changes. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Q.; Wang, T.T.; Feng, Y.; Wang, H.; Sun, F.B.; Liu, W.B. Projection of the impact of climate change and reservoir on the flow regime in the Yangtze River basin. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2025, 80, 41–60. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Peng, T.; Tian, H.; Singh, V.P.; Chen, M.; Liu, J.; Ma, H.; Wang, J. Quantitative assessment of drivers of sediment load reduction in the Yangtze River basin, China. J. Hydrol. 2020, 580, 124242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.H.; Jin, Z.W.; Zhang, G.S.; Jin, G.Q.; Li, Z.J. Analysis of cumulative mutations of the relationship between annual runoff and sediment load in the upper Yangtze River Basin based on improved double mass curve method. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2025, 39, 97–104. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. Variations in sedimentation rate and corresponding adjustments of longitudinal gradient in the cascade reservoirs of the lower Jinsha River. Water 2025, 17, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydrological Bureau of Changjiang Water Resources Commission (Ed.) Annals of the Yangtze River; Encyclopedia of China Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2003. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Bao, Y.; Tang, Q.; He, X.; Wei, J.; Collins, A.L. Spatiotemporal dynamics of non-floodplain ponded waterbodies in the upper Yangtze River Basin, China: A hydrological connectivity perspective. Appl. Geogr. 2025, 185, 103796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.X.; Yang, C.G.; Dong, B.J.; Zhang, O.Y. Sediment transport characteristics during high floods in the upper reaches of the Yangtze River. J. Yangtze River Sci. Res. Inst. 2021, 38, 6–11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hydrology Bureau of the Ministry of Water Resources of the people’s Republic of China. Annual Hydrological Report of the People’s Republic of China 1966–2020; Hydrological Bureau of the Ministry of Water Resources: Beijing, China, 2020. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Water Resources of the People’s Republic of China. China River Sediment Bulletin 2002–2024; China Water & Power Press: Beijing, China, 2024. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mu, X.M.; Zhang, X.Q.; Gao, P.; Wang, F. Theory of double mass curves and its applications in hydrology and meteorology. J. China Hydrol. 2010, 30, 47–51. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ran, L.; Wang, S.; Fan, X. Channel change at Toudaoguai Station and its responses to the operation of upstream reservoirs in the upper Yellow River. J. Geogr. Sci. 2010, 20, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbrecht, J.; Fernandez, G.P. Visualization of trends and fluctuations in climatic records. Water Resour. Bull. 1994, 30, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, C.F. A comprehensive study of the rainfall on the Susquehanna Valley. Eos Trans. Amer. Geophys. Union 1937, 18, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.J.; Ren, Y.Y.; Cao, L.J.; Zhang, S.Q.; Hu, C.Y.; Wu, X.L. Characteristics of dry-wet climate change in China during the past 60 years and its trends projection. Clim. Change Res. Lett. 2021, 10, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.J.; Du, J.Z.; Zhang, X.L.; Su, N.; Li, J.F. Variation of riverine material loads and environmental consequences on the Changjiang (Yangtze) estuary in recent decades (1955–2008). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.G.; Hu, C.H.; Liu, X.; Shi, H.L. Study on variations of runoff and sediment load in the Upper Yangtze River and main influence factors. J. Sediment. Res. 2016, 41, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.L.; Dong, X.Y.; Chen, Z.F. Sediment deposition of cascade reservoirs in the Lower Jinsha River and its impact on Three Gorges Reservoir. J. Yangtze River Sci. Res. Inst. 2016, 34, 1. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J.; Xu, Q.X. Sediment trapping effect by reservoirs in the Jinsha River basin. Adv. Water Sci. 2018, 29, 482–491. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.C.; Zhang, H.L.; Xia, S.Q.; Pang, J.Z. Runoff and sediment discharge variations and corresponding driving mechanism in Jinsha River Basin. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2023, 30, 107–115. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Wang, X. Impact of large reservoirs on runoff and sediment load in the Jinsha River Basin. Water 2023, 15, 3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Dong, X.; Du, Z.; Chen, X. Processes of water–sediment and deposition in cascade reservoirs in the lower reach of Jinsha River. J. Sediment Res. 2019, 44, 24–30. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.W.; Zhang, X.F.; Xu, Q.X.; Yue, Y. Transport characteristics and contributing factors of suspended sediment in Jinsha River in recent 50 years. J. Sediment Res. 2020, 45, 30–37. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shan, M.; Guo, C.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Z. A review of changes in hydro-sediment dynamic processes after the operation of cascade hydropower stations in the lower reaches of the Jinsha River. In Proceedings of the Conference on Theories and Innovative Applications of Water Conservancy and Hydropower Risk Management, Wuhan, China, 14 December 2021. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Wang, L.; Li, N. Analysis on the change of sediment discharge of the Yangtze River in recent 60 years. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Bas. 2018, 21, 116–123. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. Differential changes in water and sediment transport under the influence of large-scale reservoirs connected end to end in the upper Yangtze River. Hydrology 2025, 12, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.Q.; Deng, A.; Dong, X.; Qin, L.; Zhang, B. Study on the spatial-temporal variations of runoff and sediment in the lower reach of Jinsha River. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2023, 54, 1309–1322. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gu, C.J.; Mu, X.M.; Gao, P.; Zhao, G.J.; Sun, W.Y. Changes in run-off and sediment load in the three parts of the Yellow River basin, in response to climate change and human activities. Hydrol. Process. 2019, 33, 585–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, W.S.; Yu, S.Y.; Liang, S.Q.; Hu, Q.F. Assessment of the contributions of climate change and human activities to runoff variation: Case study in four subregions of the Jinsha River Basin, China. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2021, 26, 05021024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Cheng, S.; He, N.; Huang, L.; Yang, H.; Hong, F.; Ma, Y.; Chen, W.; Guo, W. Multi-scale flow regimes and driving forces analysis based on different models: A case study of the Wu River basin. Water Supply 2023, 23, 3978–3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.J.; Liu, H.H.; Yao, C.Y. Suitability of methods on the judgement of reference period and causes of sediment load variation in the Yangtze River basin, China. J. Hydrol. 2025, 662, 133855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Li, C.; Chen, M. Statistical studies of the characteristics and key influencing factors of sediment changes in the upper Yangtze River over the past 60 years. Geomorphology 2024, 466, 109414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reservoirs | Initial Storage | Controlled Basin Area (105 km2) | Storage Capacity (109 m3) | Regulating Capacity (109 m3) | Installed Capacity (GW) | Global Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gezhouba | Dec. 1988 | 10.803 | 1.58 | 0.085 | 2.7 | |

| Three Gorges | Jun. 2003 | 10.800 | 39.30 | 22.15 | 22.5 | 1 |

| Xiangjiaba | Oct. 2012 | 4.588 | 5.163 | 0.903 | 6.4 | 11 |

| Xiluodu | May 2013 | 4.544 | 12.670 | 6.46 | 13.9 | 4 |

| Wudongde | Jan. 2020 | 4.068 | 7.408 | 3.0 | 10.2 | 7 |

| Baihetan | Apr. 2021 | 4.303 | 20.627 | 10.4 | 16.0 | 2 |

| Sum | 39.106 | 86.748 | 42.998 | 71.7 |

| Hydrological Station (St.) | Location | Year of Establishment | Controlled Area (km2) | Adopted Data Series |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pingshan St. | Near the outlet of JSR | 1954 | 458,592 | 1966–2008 |

| Xiangjiaba St. | Outlet of JSR | 2008 | 458,800 | 2009−2024 |

| Zhutuo St. | Main stream of UYR | 1954 | 694,725 | 1966−2024 |

| Beibei St. | Outlet of JLR (tributary) | 1939 | 156,736 | 1966−2024 |

| Wulong St. | Outlet of WJR (tributary) | 1951 | 83,035 | 1966−2024 |

| Yichang St. | Outlet of UYR | 1946 | 1,005,501 | 1966−2024 |

| Location | Inflection Year | PBAS | PFCH | PSCH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At XJB Station | 2001 | 2013 | 1966–2000 | 2001–2012 | 2013–2024 |

| At Zhutuo Station (ZTS) | 2000 | 2013 | 1966–1999 | 2000–2012 | 2013–2024 |

| Discharged into TGR | 1997 | 2013 | 1966–1996 | 1997–2012 | 2013–2024 |

| Released from TGR | 1989 | 2003 | 1966–1988 | 1989–2002 | 2003–2024 |

| Between XJB and ZT Stations | 1992 | 2000 | 1966–1991 | 1992–1999 | 2000–2024 |

| Between ZTS and TGR inlet | 1987 | 2003 | 1966–1986 | 1987–2002 | 2003–2024 |

| Location | Period | CS | CP | CET | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSV (108t·yr−1) | SSC | SPV (mm·yr−1) | SPC | SETV (mm·yr−1) | SETC | ||

| Above XJB St. | 1966–2000 | 2.513 | / | 579.78 | / | 481.74 | / |

| 2001–2012 | 1.431 | −0.431 | 595.40 | 0.027 | 573.74 | 0.191 | |

| 2013–2024 | 0.012 | −0.995 | 648.90 | 0.119 | 582.94 | 0.210 | |

| Above ZT St. | 1966–1999 | 3.057 | / | 681.73 | / | 449.77 | / |

| 2000–2012 | 1.766 | −0.422 | 680.58 | −0.002 | 571.62 | 0.271 | |

| 2013–2024 | 0.406 | −0.867 | 766.60 | 0.124 | 576.30 | 0.281 | |

| Above TGR inlet | 1966–1996 | 4.657 | / | 760.69 | / | 578.55 | / |

| 1997–2012 | 2.390 | −0.487 | 770.81 | 0.013 | 660.46 | 0.142 | |

| 2013–2024 | 0.771 | −0.834 | 837.49 | 0.101 | 657.70 | 0.137 | |

| Above YC St. | 1966–1988 | 5.196 | / | 996.51 | / | 773.50 | / |

| 1989–2002 | 4.028 | −0.225 | 968.83 | −0.028 | 778.90 | 0.007 | |

| 2003–2024 | 0.235 | −0.955 | 950.69 | −0.046 | 849.53 | 0.098 | |

| Section XJB–ZT St. | 1966–1991 | 0.658 | / | 1032.30 | / | 538.95 | / |

| 1992–1999 | −0.012 | −1.018 | 1011.92 | −0.020 | 486.61 | −0.097 | |

| 2000–2024 | 0.335 | −0.490 | 1055.16 | 0.022 | 561.93 | 0.043 | |

| Section ZTS–TGR | 1966–1986 | 1.926 | / | 1016.38 | / | 960.26 | / |

| 1987–2002 | 0.648 | −0.663 | 954.40 | −0.061 | 934.25 | −0.027 | |

| 2003–2024 | 0.347 | −0.820 | 1007.50 | −0.009 | 885.46 | −0.078 | |

| Location | Periods and Their Codes | CP (%) | CET (%) | CCL (%) | CHA (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Above XJB St. | 1966–2000 | Base Period | / | / | / | / |

| 2001–2012 | Change−I | −6.3 | 0.4 | −5.8 | 105.8 | |

| 2013–2024 | Change−Ⅱ | −12.0 | 0.2 | −11.7 | 111.7 | |

| Above ZT St. | 1966–1999 | Base Period | / | / | / | / |

| 2000–2012 | Change−I | 0.5 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 98.9 | |

| 2013–2024 | Change−Ⅱ | −14.3 | 0.3 | −14.0 | 114.0 | |

| Above TGR inlet | 1966–1996 | Base Period | / | / | / | / |

| 1997–2012 | Change−I | −2.7 | 0.3 | −2.4 | 102.4 | |

| 2013–2024 | Change−Ⅱ | −12.1 | 0.2 | −11.9 | 111.9 | |

| Above YC St. | 1966–1988 | Base Period | / | / | / | / |

| 1989–2002 | Change−I | 12.4 | 0.0 | 12.5 | 87.5 | |

| 2003–2024 | Change−Ⅱ | 4.8 | 0.1 | 4.9 | 95.1 | |

| Section XJB–ZT St. | 1966–1991 | Base Period | / | / | / | / |

| 1992–1999 | Change−I | 2.0 | −0.1 | 1.9 | 98.1 | |

| 2000–2024 | Change−Ⅱ | −4.5 | 0.1 | −4.4 | 104.4 | |

| Section ZTS-TGR | 1966–1986 | Base Period | / | / | / | / |

| 1987–2002 | Change–I | 9.2 | 0.0 | 9.2 | 90.8 | |

| 2003–2024 | Change–Ⅱ | 1.1 | –0.1 | 1.0 | 99.0 | |

| Arithmetic Mean | Change–I | 2.5 | 0.2 | 2.8 | 97.3 | |

| Change–Ⅱ | –6.2 | 0.1 | –6.0 | 106.0 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, S. Spatial and Temporal Changes in Suspended Sediment Load and Their Contributing Factors in the Upper Reaches of the Yangtze River. Earth 2025, 6, 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth6040152

Wang S. Spatial and Temporal Changes in Suspended Sediment Load and Their Contributing Factors in the Upper Reaches of the Yangtze River. Earth. 2025; 6(4):152. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth6040152

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Suiji. 2025. "Spatial and Temporal Changes in Suspended Sediment Load and Their Contributing Factors in the Upper Reaches of the Yangtze River" Earth 6, no. 4: 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth6040152

APA StyleWang, S. (2025). Spatial and Temporal Changes in Suspended Sediment Load and Their Contributing Factors in the Upper Reaches of the Yangtze River. Earth, 6(4), 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth6040152