Cascade Control Based on Sliding Mode for Trajectory Tracking of Mobile Robot Formation †

Abstract

1. Introduction

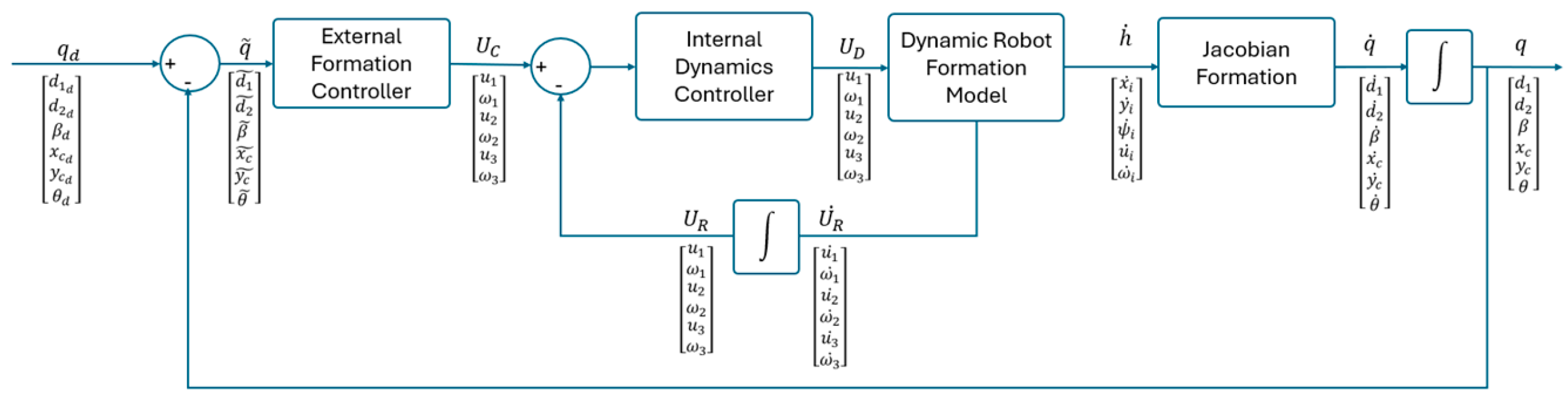

2. Modeling

2.1. Kinematic and Dynamic Model of the Mobile Robot

2.2. Mobile Robot Formation Model

3. Controllers

3.1. PD Formation Controller without Dynamic Compensation (PD)

3.2. SMC Formation Controller without Dynamic Compensation

3.3. PD Formation Controller with Dynamic Compensation (PD-DI)

3.4. PD Formation Controller with Dynamic Sliding Mode Control (PD-SMCV)

3.5. Sliding Mode Formation Control with Dynamic Sliding Mode Dynamic Compensation (SMC-SMCV)

3.6. Stability Analysis of the PD Formation Controller with Dynamic Compensation (PD-DI)

3.7. Stability Analysis of the PD Formation Controller with Dynamic Sliding Mode Control (PD-SMCV)

3.8. Stability Analysis of the Sliding Mode Formation Control with Dynamic Sliding Mode Dynamic Compensation (SMC-SMCV)

4. Results

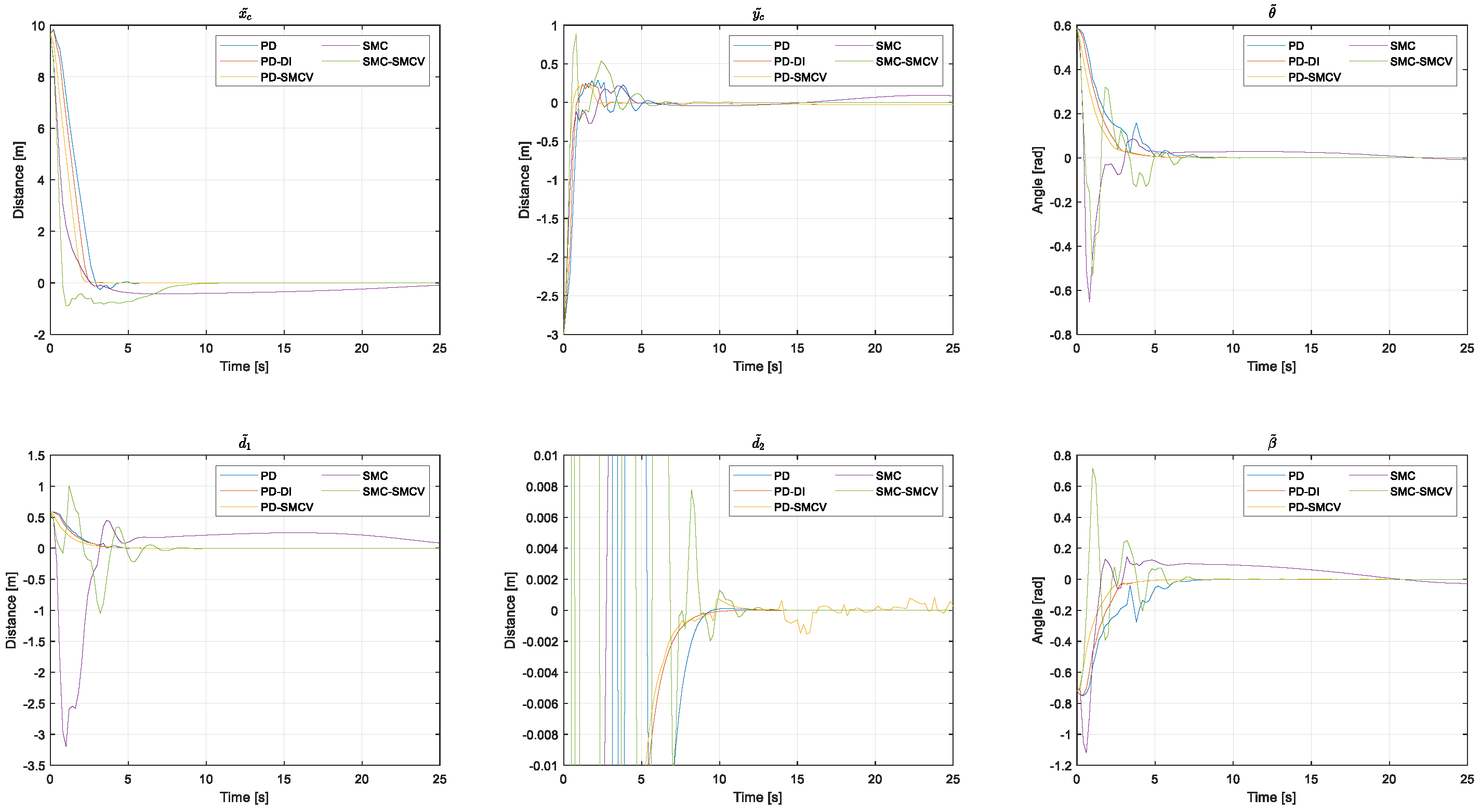

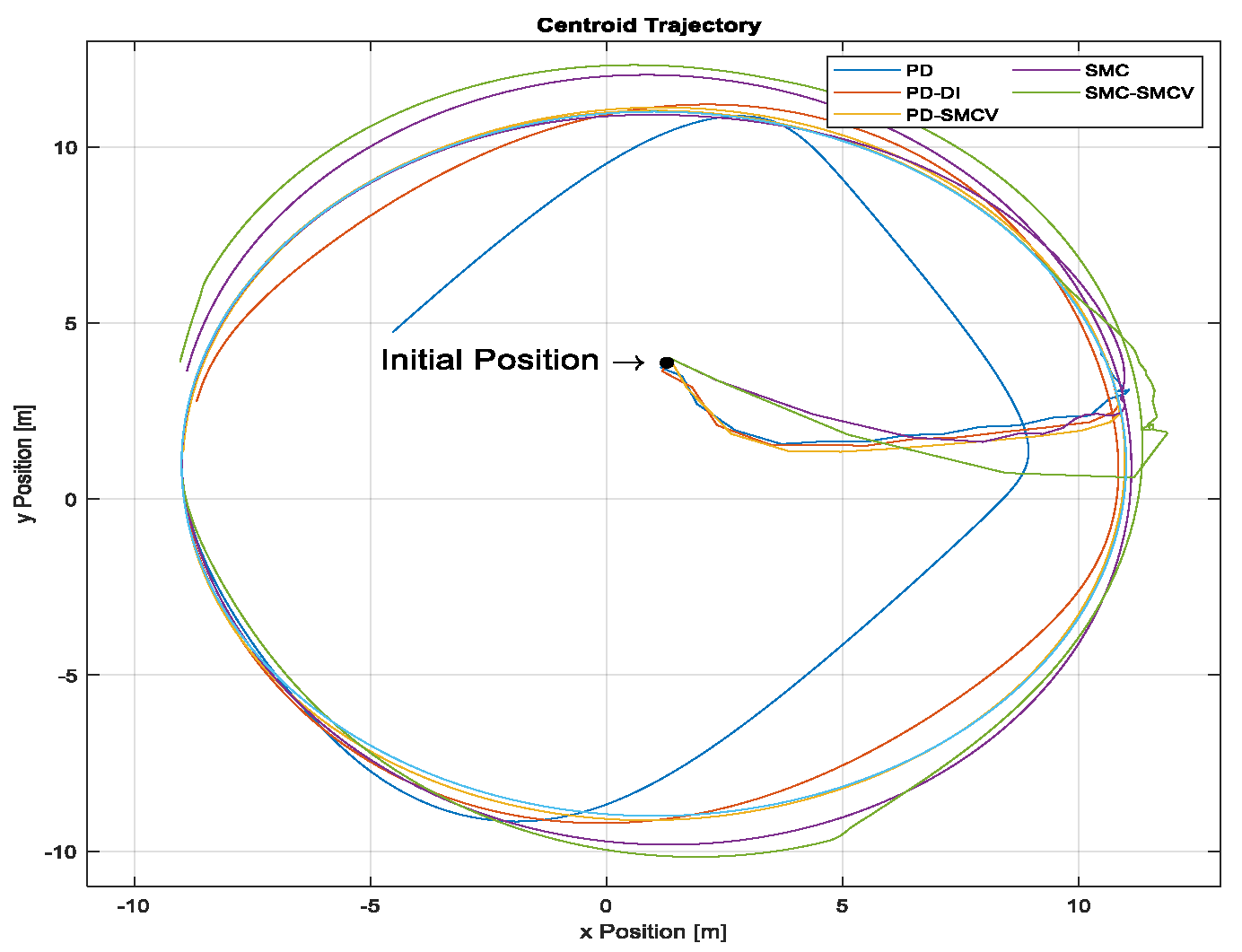

4.1. Experiment 1: Path Following without Disturbance

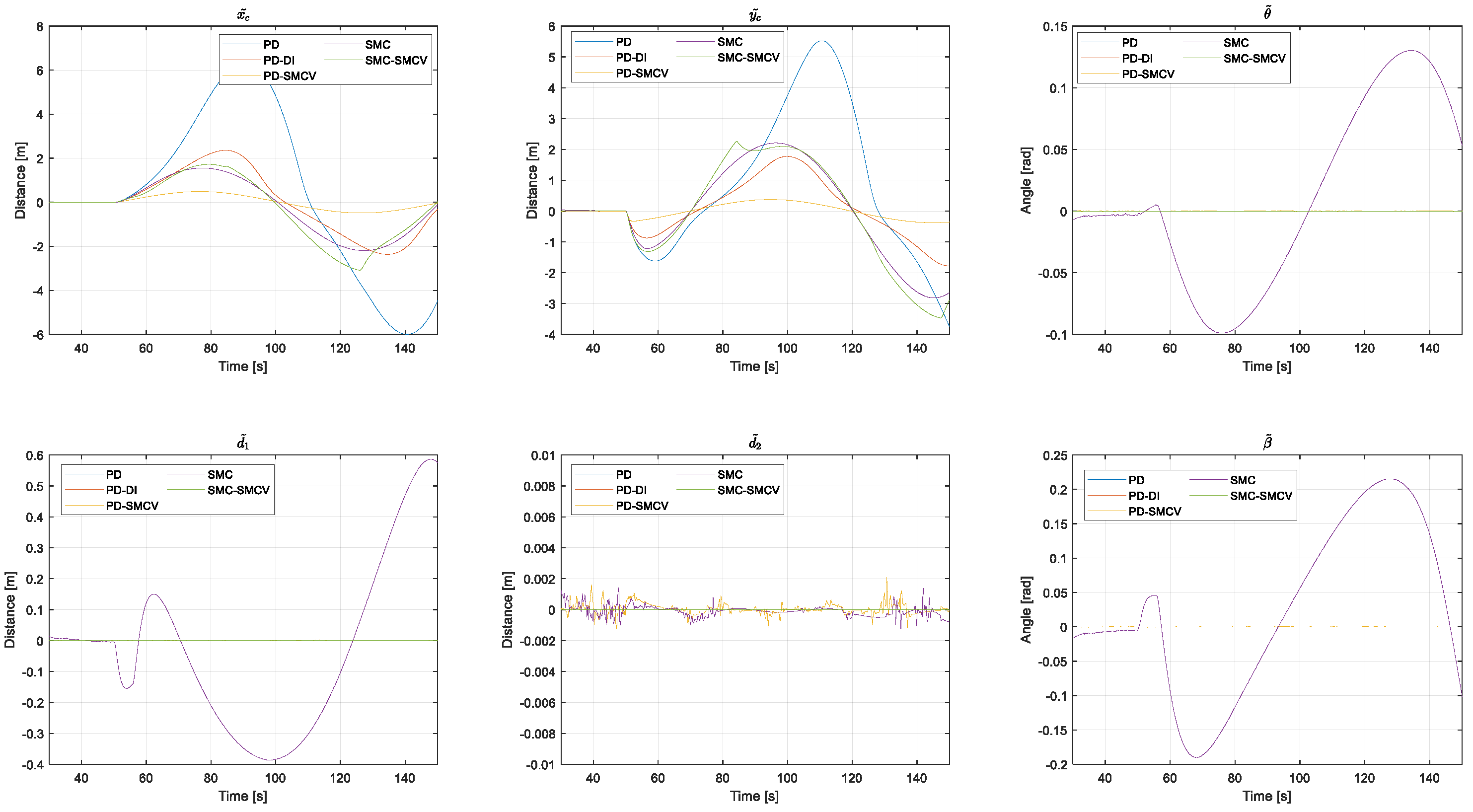

4.2. Experiment 2: Path Following Applying Dynamic Disturbance

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- An, X.; Wu, C.; Lin, Y.; Lin, M.; Yoshinaga, T.; Ji, Y. Multi-Robot Systems and Cooperative Object Transport: Communications, Platforms, and Challenges. IEEE Open J. Comput. Soc. 2023, 4, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Li, B.; Shah, A.; Qin, N.; Huang, D. Fuzzy Sliding Mode Control for a Quadrotor UAV. DDCLS 2019, 8, 672–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Nie, Z.; Gong, Z.; Liu, X.-J. An Omnidirectional Transportation System With High Terrain Adaptability and Flexible Configurations Using Multiple Nonholonomic Mobile Robots. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 6060–6067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, P. Robust multi-mobile robot formation control: A fully actuated system control approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd Conference on Fully Actuated System Theory and Applications (FASTA), Shenzhen, China, 10–12 May 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leica, P.; Balseca, J.; Cabascango, D.; Chávez, D.; Andaluz, G.; Andaluz, V.H. Controller Based on Null Space and Sliding Mode (NSB-SMC) for Bidirectional Teleoperation of Mobile Robots Formation in an Environment with Obstacles. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Fourth Ecuador Technical Chapters Meeting (ETCM), Guayaquil, Ecuador, 11–15 November 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Nie, J.; Sun, J.; Chen, G.; Zou, L. Adaptive sliding Mode Control for Nonholonomic Mobile Robots based on Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC), Nanchang, China, 3–5 June 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mevo, B.B.; Saad, M.R.; Fareh, R. Adaptive Sliding Mode Control of Wheeled Mobile Robot with Nonlinear Model and Uncertainties. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Canadian Conference on Electrical & Computer Engineering (CCECE), Quebec, QC, Canada, 13–16 May 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juang, C.-F.; Lu, C.-H.; Huang, C.-A. Navigation of Three Cooperative Object-Transportation Robots Using a Multistage Evolutionary Fuzzy Control Approach. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 3606–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, D.; Chen, C.L.P.; Xu, H. Fuzzy Swarm Control Based on Sliding-Mode Strategy with Self-Organized Omnidirectional Mobile Robots System. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2022, 52, 2262–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Canale, E.S.; Costa, O.L.V. Formation Static Output Control of Linear Multi-Agent Systems with Hidden Markov Switching Network Topologies. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 132278–132289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Deng, F.; Wei, W.; Wan, F. Formation Tracking Control of Networked Systems with Time-Varying Delays and Sampling Under Fixed and Markovian Switching Topology. IEEE Trans. Control Netw. Syst. 2022, 9, 601–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Li, Z.; Dong, Y.; Xi, H. Markovian-Based Fault-Tolerant Control for Wheeled Mobile Manipulators. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2012, 20, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Xiang, S.; Sun, S.; Cai, Y.; Wang, S. Formation Control and Obstacle Avoidance for Multi-Robot Systems. In Proceedings of the 2022 First International Conference on Cyber-Energy Systems and Intelligent Energy (ICCSIE), Shenyang, China, 14–15 January 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, A.; Morán, A. Leader-Follower Formation Control of Nonholonomic Mobile Robots. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE ANDESCON, Quito, Ecuador, 13–16 October 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adderson, R.; Akbari, B.; Pan, Y.; Zhu, H. Multileader and Role-Based Time-Varying Formation Using GP Inference and Sliding-Mode Control. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boo, J.; Chwa, D. Fuzzy Integral Sliding Mode Observer-Based Formation Control of Mobile Robots with Kinematic Disturbance and Unknown Leader and Follower Velocities. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 76926–76938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Zhao, J. Research on Tracking Control of Circular Trajectory of Robot Based on the Variable Integral Sliding Mode PD Control Algorithm. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 204194–204202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andaluz, G.M.; Andaluz, V.H.; Terán, H.C.; Arteaga, O.; Chicaiza, F.A.; Varela, J.; Ortiz, J.S.; Pérez, F.; Rivas, D.; Sánchez, J.S.; et al. Modeling Dynamic of the Human-Wheelchair System Applied to NMPC. In Intelligent Robotics and Applications. ICIRA 2016; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andaluz, G.M.; Leica, P.; Herrera, M.; Morales, L.; Camacho, O. Hybrid Controller based on Null Space and Consensus Algorithms for Mobile Robot Formation. Emerg. Sci. J. 2022, 6, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, V.; Espinosa, V.; Chávez, D.; Leica, P.; Camacho, O. Trajectory tracking for quadcopter’s formation with two control strategies. 2016 IEEE Ecuador Technical Chapters Meeting, Guayaquil, Ecuador, 12—14 October 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, B.; Carelli, R. Robot control with inverse dynamics and non-linear gains. Lat. Am. Appl. Res. 2003, 33, 393–397. [Google Scholar]

| PD | 0.536 | 2.034 | 0.719 | 207.505 | 10.258 | 0.453 |

| PD-DI | 0.361 | 1.770 | 0.617 | 187.605 | 7.691 | 0.319 |

| PD-SMCV | 0.481 | 1.358 | 1.104 | 156.313 | 6.212 | 0.480 |

| SMC | 0.476 | 1.960 | 0.479 | 38.100 | 4.479 | 0.727 |

| SMC–SMCV | 6.195 | 1.377 | 1.494 | 44.890 | 4.940 | 0.599 |

| Controller | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD | 0.3726 | 2.0811 | 0.7767 | 1.80E+03 | 708.0329 | 0.3766 |

| PD-DI | 0.3307 | 1.8614 | 0.5798 | 328.021 | 99.8266 | 0.2986 |

| PD-SMCV | 0.211 | 1.93 | 0.3269 | 79.8945 | 8.5865 | 0.2118 |

| SMC | 20.4928 | 1.4243 | 2.8142 | 221.6967 | 269.3052 | 0.9635 |

| SMC–SMCV | 1.3112 | 1.5882 | 0.557 | 275.4384 | 335.2991 | 0.271 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Camino, A.; Villegas, A.; Pérez, E.; López, R.; Andaluz, G.M.; Leica, P. Cascade Control Based on Sliding Mode for Trajectory Tracking of Mobile Robot Formation. Eng. Proc. 2024, 77, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2024077013

Camino A, Villegas A, Pérez E, López R, Andaluz GM, Leica P. Cascade Control Based on Sliding Mode for Trajectory Tracking of Mobile Robot Formation. Engineering Proceedings. 2024; 77(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2024077013

Chicago/Turabian StyleCamino, Alejandro, Andrés Villegas, Esteban Pérez, Richard López, Gabriela M. Andaluz, and Paulo Leica. 2024. "Cascade Control Based on Sliding Mode for Trajectory Tracking of Mobile Robot Formation" Engineering Proceedings 77, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2024077013

APA StyleCamino, A., Villegas, A., Pérez, E., López, R., Andaluz, G. M., & Leica, P. (2024). Cascade Control Based on Sliding Mode for Trajectory Tracking of Mobile Robot Formation. Engineering Proceedings, 77(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2024077013