1. Introduction

In recent decades, and especially in recent years, we have witnessed an exponential development of technology that follows the growing needs and demands of users, whose numbers are constantly increasing. These demands may be related to the application of technology in industry and science (driverless cars, robotics, medicine, artificial intelligence, etc.), which is why an increasing impact on society is inevitable. As radio networks evolve, their market introduction is shifting to a higher-frequency range. Apart from the fact that the frequency spectrum is fairly well occupied and distributed over the years, higher frequencies offer more efficient solutions for the user’s requirements. However, with the offer of mobile networks in a very high-frequency range, there is a growing awareness of the need to protect oneself from electromagnetic radiation—a topic that many scientists in this field, as well as the authors of this scientific paper, are concerned with.

Researchers focus on the development of building materials for buildings occupied by people with the aim of protecting them from EM radiation, as well as testing the EM shielding efficiency (ESE) of buildings for the same purpose. Back in 2003, Wang and Hung examined the ESE of charcoal made from six types of wood. The investigations showed that charcoal from Western Hemlock and Fortune Paulownia yielded a maximum ESE value of 36 and 61 dB at a wood carbonization temperature of 1000 °C [

1]. L. Folgueras and other authors published a conference article in 2009 describing paints applied to a metal surface—paints containing carbonyl iron and/or polyaniline and polyurethane. These paints can absorb 60–80% of the incident EM waves [

2]. In 2014, D. Micheli and other authors published the results of a study that measured the EM shielding effectiveness (

SE) on buildings dating back to the Roman Empire, the mid-19th century and modern reinforced concrete buildings in Rome, and showed that the field strength can be reduced by 80 dB [

3]. H. Pan et al. (2017) talks about EMI shielding of ceramic materials reinforced with carbon nanowires [

4]. In addition, D. D. L. Chung (2020) gives an overview of the best materials that can be used for EM interference shielding and concludes that the most effective materials are those containing carbon and metals [

5]. In 2022, Ting-Ting Liu and other authors, also, raise awareness of the need to live in a healthier environment and describe materials that help reduce EM pollution—cement, concrete, ceramics, etc. [

6].

In reviewing the available literature, it was found that the need for protection from EM radiation is widespread and is increasing with the development of technology. The authors of this paper continue the research in the same direction, combining non-conductive dielectric materials to reduce EM exposure. These materials can find application in minimizing RF crosstalk, RF noise and interference, various digital applications and also in many industries and living spaces. All this can be achieved by a controlled selection of materials with suitable electrical, chemical and mechanical properties.

In the following chapters, it is shown how several layers of composite material affect the reduction (attenuation) of the transmission parameter S21 when the above structure is placed in a circular waveguide in the frequency range from 1.5 GHz to 6 GHz.

2. Electromagnetic Shielding

There are various methods of protection from EM nonionizing radiation, but one of the most effective methods is precise EM shielding of the area in question [

7,

8].

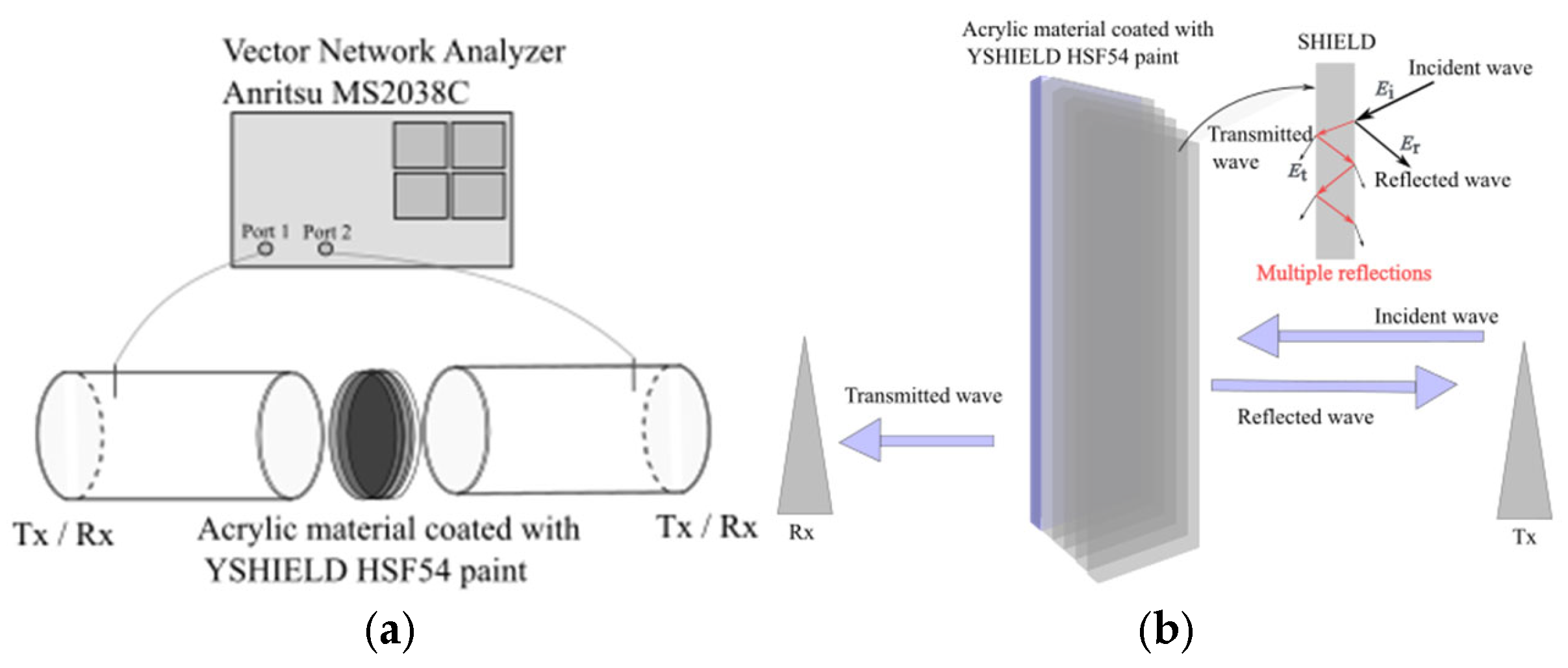

Figure 1a,b shows the scheme for measuring the strength of the EM wave when passing through the dielectric material (with a protective and conductive shield) and what happens to the wave as it passes through a multilayer structure.

The measured values of the electric field strength of the unshielded and shielded object can be used to determine the shielding efficiency (

SE):

where

Eush—electric field strength when passing through unshielded surface,

Esh—electric field strength when passing through shielded surface,

or, in the case of the measurement of the transmission parameter:

The purpose of the material used to cover a certain object is to absorb part of the wave energy and reflect part of it. Therefore, even if the measurements were carried out in a room with an EM echo, the measured values of the reflection parameters give us an overall picture of the amount of energy reflected by the EM shielding. Therefore, it is necessary to choose a material that has high reflection and absorption properties and low transmission, thus serving as a shield against EM radiation.

3. Carbon-Based Materials for Protection Against Electromagnetic Radiation

A carbon-based material is a material that contains (in addition to water, preservatives, additives, and pure acrylic dispersion) natural graphite and black carbon and as such is a composite material. Composite materials (especially those reinforced with fibers) should be arranged in multiple layers to ensure high structural strength and good mechanical properties. To achieve high ESE, these fibers are made of highly conductive elements [

9].

So, for materials that are expected to have high shielding efficiency (

SE), they should have a high electrical conductivity σ, and those containing carbon can have a conductivity of up to several thousand S/m. Furthermore, by controlling the proportion of carbon in the total mass, it is possible to influence the increase in conductivity

σ and therefore

SE. These materials include materials with carbon black, graphite, carbon fibers, carbon nanoparticles (CNTs) and graphene [

8].

One of the materials that meet the aforementioned characteristics of good conductivity and satisfactory SE is YSHIELD HSF54.

The composite paint YSHIELD HSF54 is a water-based, carbon-loaded conductive coating designed for EM shielding. The manufacturer tested YSHIELD HSF54 paint by conducting measurements in the frequency range from 600 MHz to 40 GHz, in accordance with the IEEE Std 299-2006 standard. The shielding effectiveness achieved ranged from −40 dB to −90 dB when one liter of paint was applied to 4 m

2. These values indicate that the material can attenuate incident EM radiation by up to 99.9%, depending on frequency and layer thickness [

10]. For comparison, widely used metallic shielding materials, such as copper or aluminum foils of similar thickness, typically achieve a shielding effectiveness above 80 dB in the same frequency range. While metallic foils can provide higher attenuation, YSHIELD HSF54 offers the advantage of easier application as a coating on complex surfaces and the possibility of creating multilayer composite structures. This makes it a suitable choice for experimental studies of multilayer conductive coatings and their effect on wave propagation.

The next chapter deals with exactly this paint, which can be applied to walls and substrates for the purpose of attenuation of the EM field.

4. Results of Theoretical Calculations of EM Field Propagation Through a Multilayer Structure

The theoretical and practical part of the paper is based on the calculation and measurement of the transmission parameter

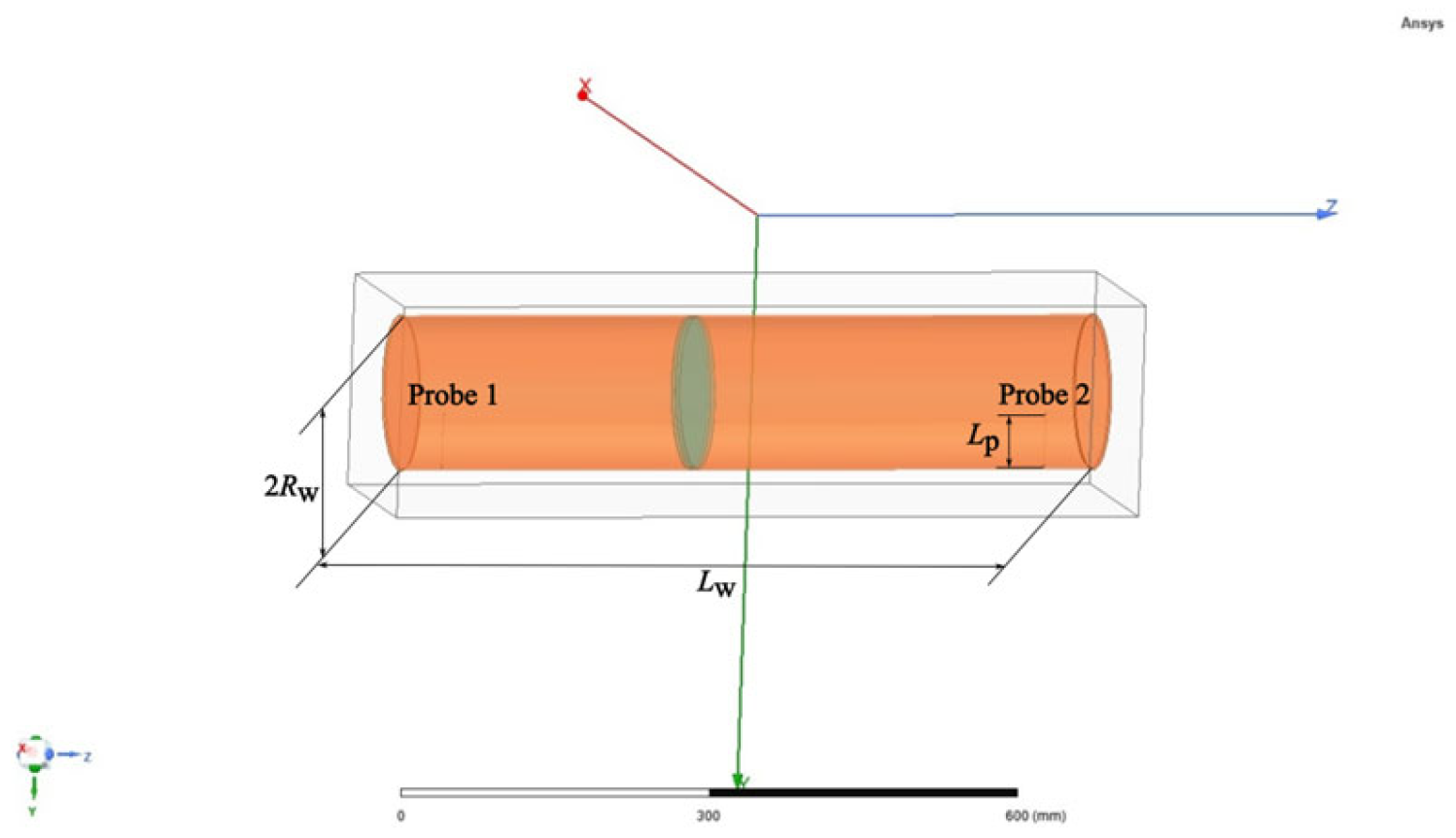

S21. The simulation calculations were carried out using the computer program Ansys HFSS v22.1, and the schematic of the calculation model is shown in

Figure 2. This figure shows the placement of several layers of Plexiglas in a circular waveguide with a single coating, i.e., a layer of conductive YSHIELD HSF54 paint. The electric field is passed through the above structures and the transmission at port 2 is determined.

Simulation calculations (and subsequent measurements) were carried out for only one layer of Plexiglas with several layers of coating.

The input parameters (geometric and electromagnetic) required to calculate the transmission parameter S21 are as follows:

- -

The length of the waveguide

Lw with a circular cross-section is 700 mm, while the probe length

Lp for the corresponding frequencies range is 52 mm. There are two probes (port 1 and port 2) in the waveguide, which are 45 mm away from the back wall of the waveguide. The inner diameter of the Al waveguide 2

Rw is 150 mm, while the Al wall thickness is 2 mm. In addition, Plexiglas panels are inserted into the waveguide (300 mm from wall 2), to which one or more layers of YSHIELD HSF54 paint are applied (

Figure 1a and

Figure 2).

Plexiglas (polymethyl methacrylate—PMMA) is a strong, transparent and weather-resistant structure (more precisely, a polymer). Its parameters are listed in

Table 1. YSHIELD HSF54 stands for a carbon-based conductive material (described in

Section 3), and the simulation parameters in ANSYS HFSS are also listed in

Table 1.

Simulation Calculations of the Propagation of the EM Field Through a Multilayer Structure in a Circular Waveguide: A Single Plexiglas Plate with Multiple Layers of YSHIELD HSF54 Paint

The idea was to determine the

S21 parameter, but for the case where there is only one layer of Plexiglas in the waveguide and several layers of YSHIELD paint are applied to it.

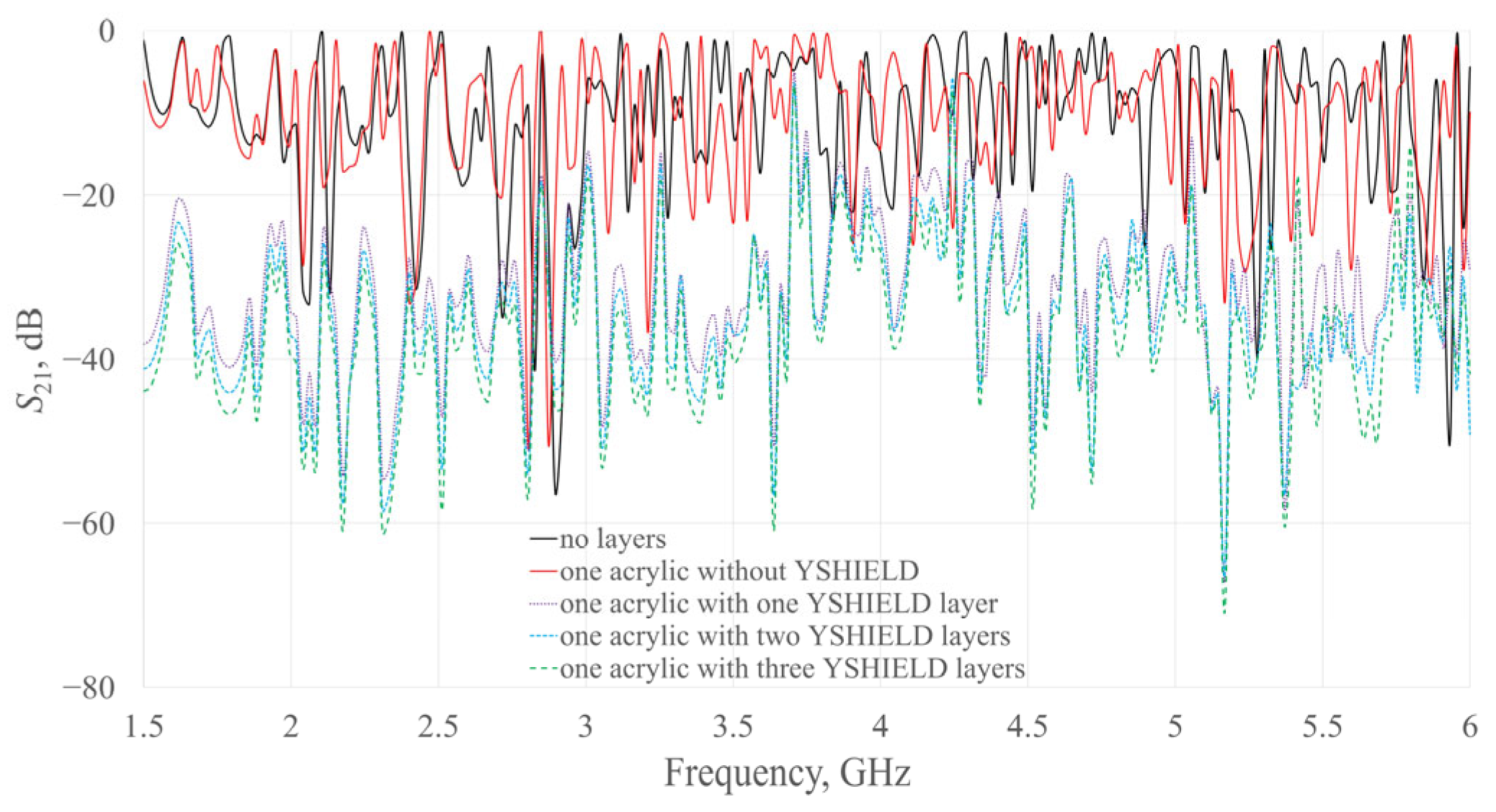

Figure 3 illustrates the above situation, and the transmission values at significant frequencies can be found in

Table 2. The reference values refer to an empty waveguide with no material layer to attenuate the EM field. This curve is shown in black in

Figure 3 and clearly indicates that placing a multilayer structure in the waveguide significantly attenuates the EM field strength.

Table 2 also presents the

S21 values when there are no obstacles in the waveguide through which the field propagates.

Since the theoretical calculations were made for a wide frequency range (LTE and 5G), the mean value of the

S21 parameters was calculated for each geometry case, and the results are summarized in

Table 3.

Figure 3 and

Table 2 and

Table 3 show very clearly what happens to the EM field when it passes through a multilayer structure made of Plexiglas and one or more layers of conductive carbon-based paint. The results of the simulation calculations show that the first layer of paint on the Plexiglas has the greatest influence on the reduction of the

S21 parameter. The average difference (over the entire frequency range) is 20 dB (which represents a very large contribution to the attenuation of the EM field on the receiving side).

5. Measurement of the Transmission Parameter S21 When an EM Wave Passes Through a Composite Material and Validation of the Theoretical Results

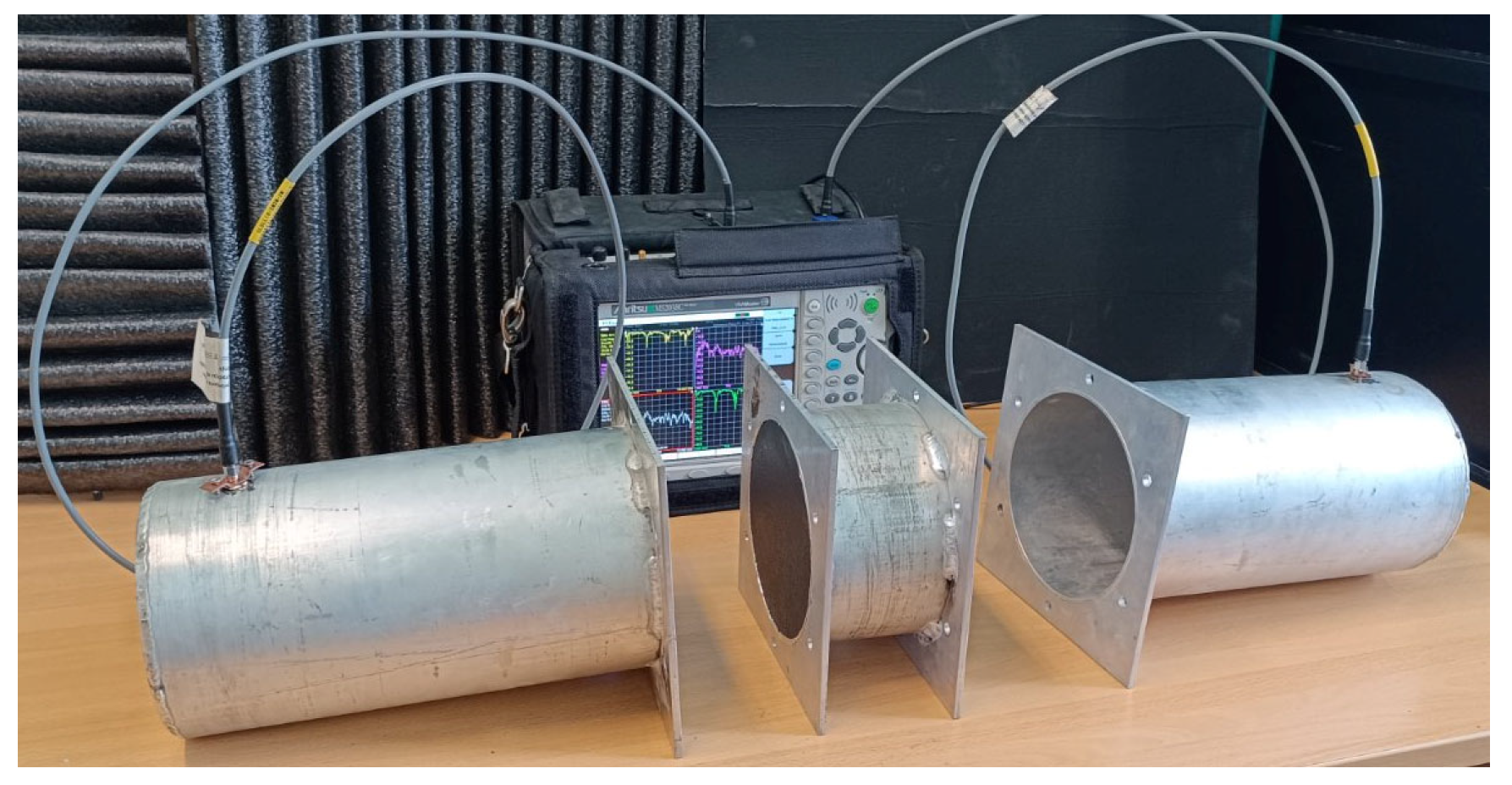

The transmission parameter

S21 was measured using an Anritsu MS2038C VNA Master & Spectrum Analyzer (Anritsu Corporation, Atsugi, Kanagawa, Japan), covering 5 kHz–20 GHz frequency range. Circular disks of acrylic (Plexiglas) with a thickness of 4 mm and a diameter of 150 mm, coated with YSHIELD HSF54 carbon-based paint, were inserted into an aluminum waveguide of the same diameter (see

Figure 1a and

Figure 4). The transmission parameter

S21 was measured when an EM wave passed through an acrylic material to which the conductive paint YSHIELD HSF54 was applied (

Figure 5).

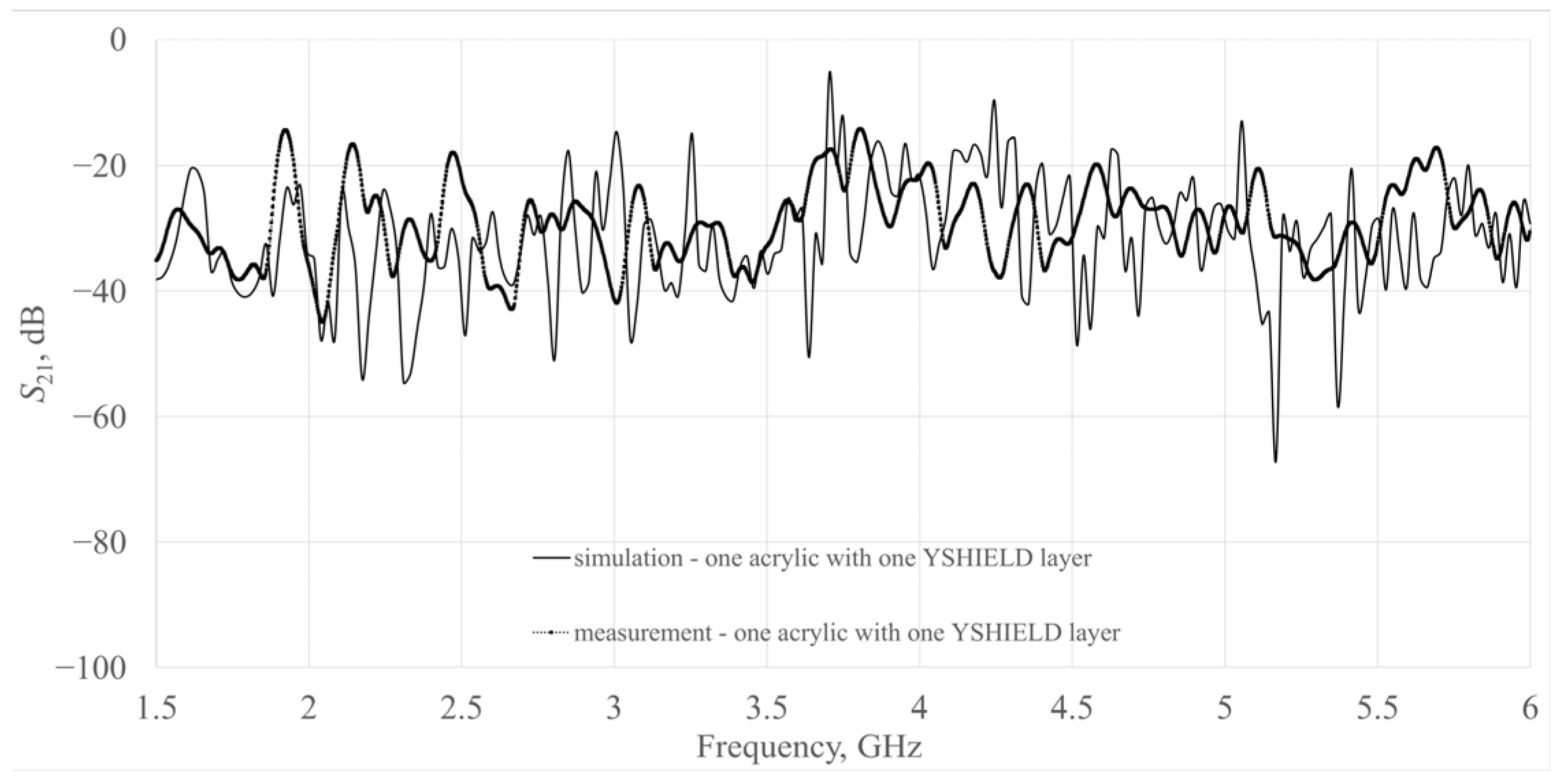

The measurement of transmission in the waveguide was performed to confirm theoretical studies on the behavior of the EM field when passing through a multilayer structure made of a composite material. The laboratory model always differs from the model created in ANSYS HFSS—the measurement conditions, EM and geometrical parameters of the structure can never be identical, which is why there are discrepancies between the simulation and measurement results obtained. However,

Figure 5 shows a very good agreement between the calculated and measured values, which leads us to the conclusion that the entire system, from design, settings to implementation, has been successfully implemented.

In the future, there are plans to apply the protective, conductive coating to a different substrate that is better suited to the environment in which people live, e.g., on concrete walls.

6. Conclusions

The idea of this paper is to present the transmission (transmission parameters Sij, for i ≠ j) of EM waves through multilayer structures, supported by measurement and simulation results, rather than to report results for a specific paint. A simulation model of a multilayer structure was developed, with the EM parameters of each layer adjusted according to available data on the materials used.

The layers are made using a coating with carbon-based particles that are applied to plexiglass—one Plexiglas and several layers of conductive paint. Plexiglas is the material that serves as the carrier of the absorbent (protective) layer. The fundamental parameter determined by the measurement and simulation calculation is the transmission parameter S21. The measurements performed were made by measurements on layered structures in a circular waveguide, where YSHIELD HSF54 absorber paint was used for coating. The simulation calculation of the S21 parameter was carried out in the ANSYS HFSS program by creating a model geometrically aligned with the measuring waveguide set. The parameters of the absorber layer during simulation are aligned with the parameters of the layer used during measurements. The results cover a wide range of frequencies (from 1.5 to 6 GHz) and show a very low transmission of EM wave energy in the entire spectrum. It has been shown that applying just one layer of YSHIELD HSF54 to plexiglass can reduce the transmission parameter S21 by over 20 dB.

The deviations of the simulation results from the measurements are due to deviations in the geometric design of the model (layer thickness, etc.) as well as deviations in the values of the EM parameters of the coating and plexiglass. However, it can be said that the results of the measurements and the simulation calculation match very well over the entire frequency range of interest. Furthermore, by increasing the number of layers of the conductive coating, the parameter S21 is additionally attenuated.

This research shows that shielding, which is used as a method of protection against EM radiation in a large number of devices, can also be used in procedures to protect spaces in which people live, by selecting new materials and structures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.M. and S.R.; methodology, S.R.; software, V.M. and S.R.; validation, V.M.; formal analysis, V.M.; investigation, V.M.; resources, V.M.; data curation, V.M., B.P. and S.R.; writing—original draft preparation, V.M.; writing—review and editing, B.P.; visualization, V.M.; supervision, S.R., B.P. and I.B.; project administration, V.M.; funding acquisition, V.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Faculty of Electrical Engineering, Computer Science and Information Technology Osijek, project: “Threat Detection System for Wireless Network Environments (SOS-BMO)”. Project code: 581-UNIOS-33. This research was funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU. However, the views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Commission. Neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be held responsible for them.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, S.-Y.; Hung, C.-P. Electromagnetic shielding efficiency of the electric field of charcoal from six wood species. J. Wood Sci. 2003, 49, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folgueras, L.d.C.; Alves, M.A.; Rezende, M.C. Electromagnetic Radiation Absorbing Paints Based on Carbonyl Iron and Polyaniline. In Proceedings of the SBMO/IEEE MTT-S International Microwave and Optoelectronics Conference (IMOC), Belem, Brazil, 6 November 2009; pp. 510–513. [Google Scholar]

- Micheli, D.; Delfini, A.; Santoni, F.; Volpini, F.; Marchetti, M. Measurement of Electromagnetic Field Attenuation by Building Walls in the Mobile Phone and Satellite Navigation Frequency Bands. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2014, 14, 698–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Yin, X.; Xue, J.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, L. Microstructures and EMI shielding properties of composite ceramics reinforced with carbon nanowires and nanowires-nanotubes hybrid. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 12221–12231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, D.D.L. Materials for electromagnetic interference shielding. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 255, 123587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.-T.; Cao, M.-Q.; Fang, Y.-S.; Zhu, Y.-H.; Cao, M.-S. Green building materials lit up by electromagnetic absorption function: A review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 112, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Dai, M.; Guo, Q.; Yang, D.; Yin, D.; Hu, S.; Qiu, F.; Wang, Y.; Xue, Z. High-efficiency electromagnetic shielding of three-dimensional laminated Wood/Cu/Ni composites. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 697, 134430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.-D.; Choi, C.-G. Recent advances in multifunctional electromagnetic interference shielding materials. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cellozi, S.; Araneo, R.; Lovat, G. Electromagnetic Shielding, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- YSHIELD. Available online: https://www.yshield.com/en/yshield/abschirmfarben/abschirmfarbe_139_1070/ (accessed on 3 October 2025).

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |