Fuzzy-Logic-Based Intelligent Control of a Cabinet Solar Dryer for Plantago major Leaves Under Real Climatic Conditions in Tashkent †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Experimental Solar Dryer Configuration

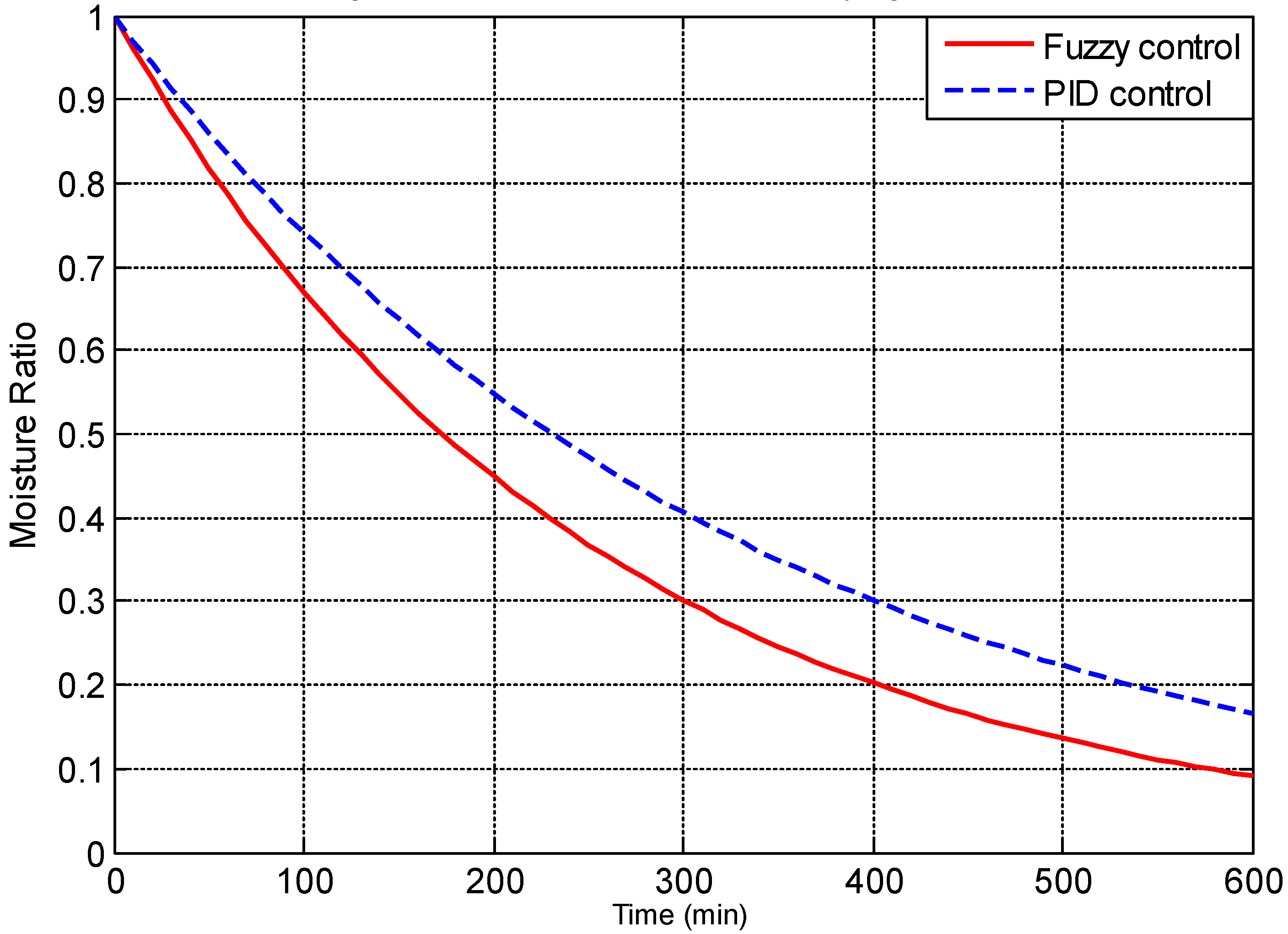

2.2. Dynamic Modeling of the Drying Process

2.2.1. Thermal Model

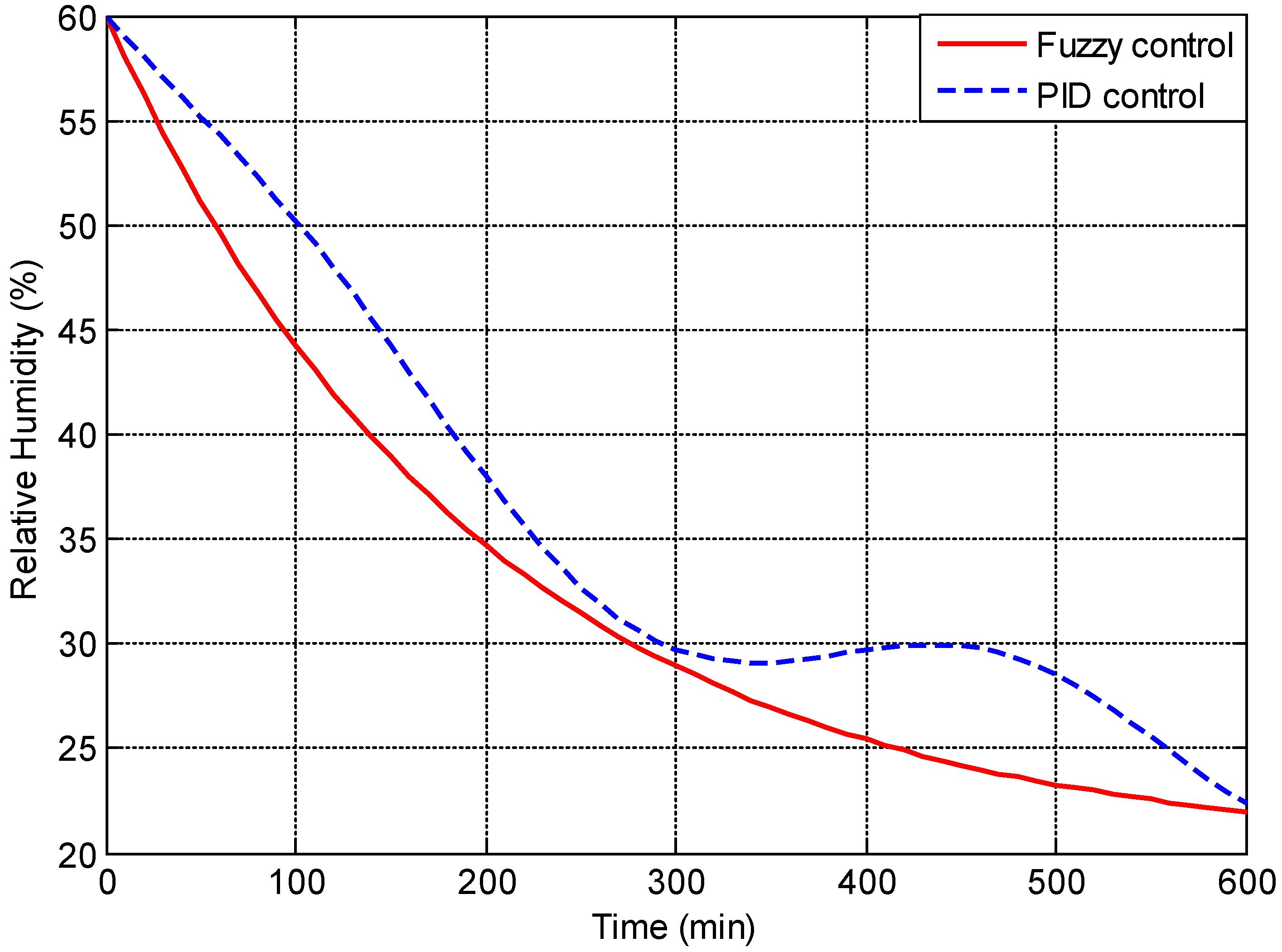

2.2.2. Hygrometric Model

2.2.3. Model–Control Integration

2.3. Design of the Mamdani Fuzzy Inference System

2.3.1. Inputs and Output

2.3.2. Membership Functions

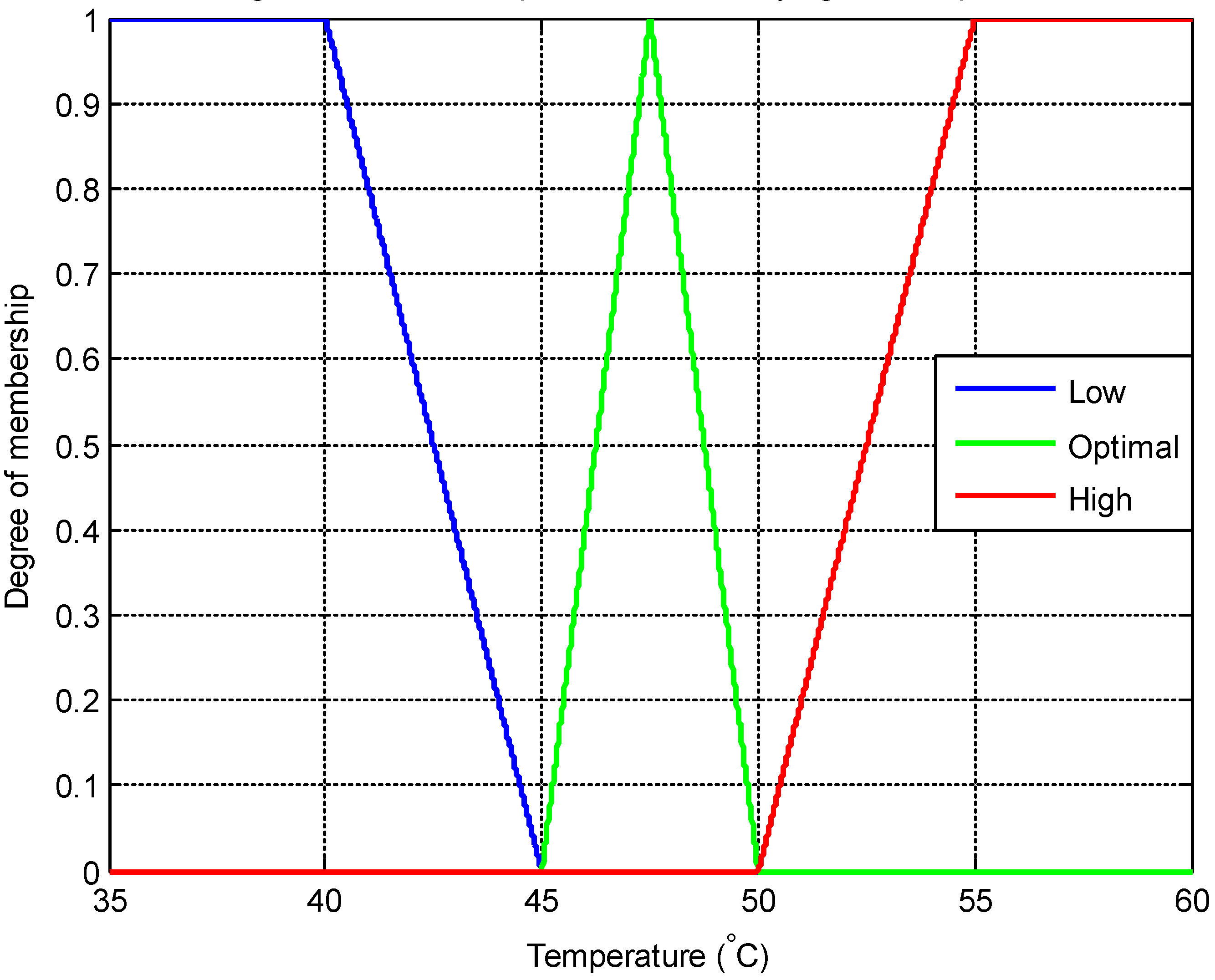

Drying Air Temperature Membership Functions

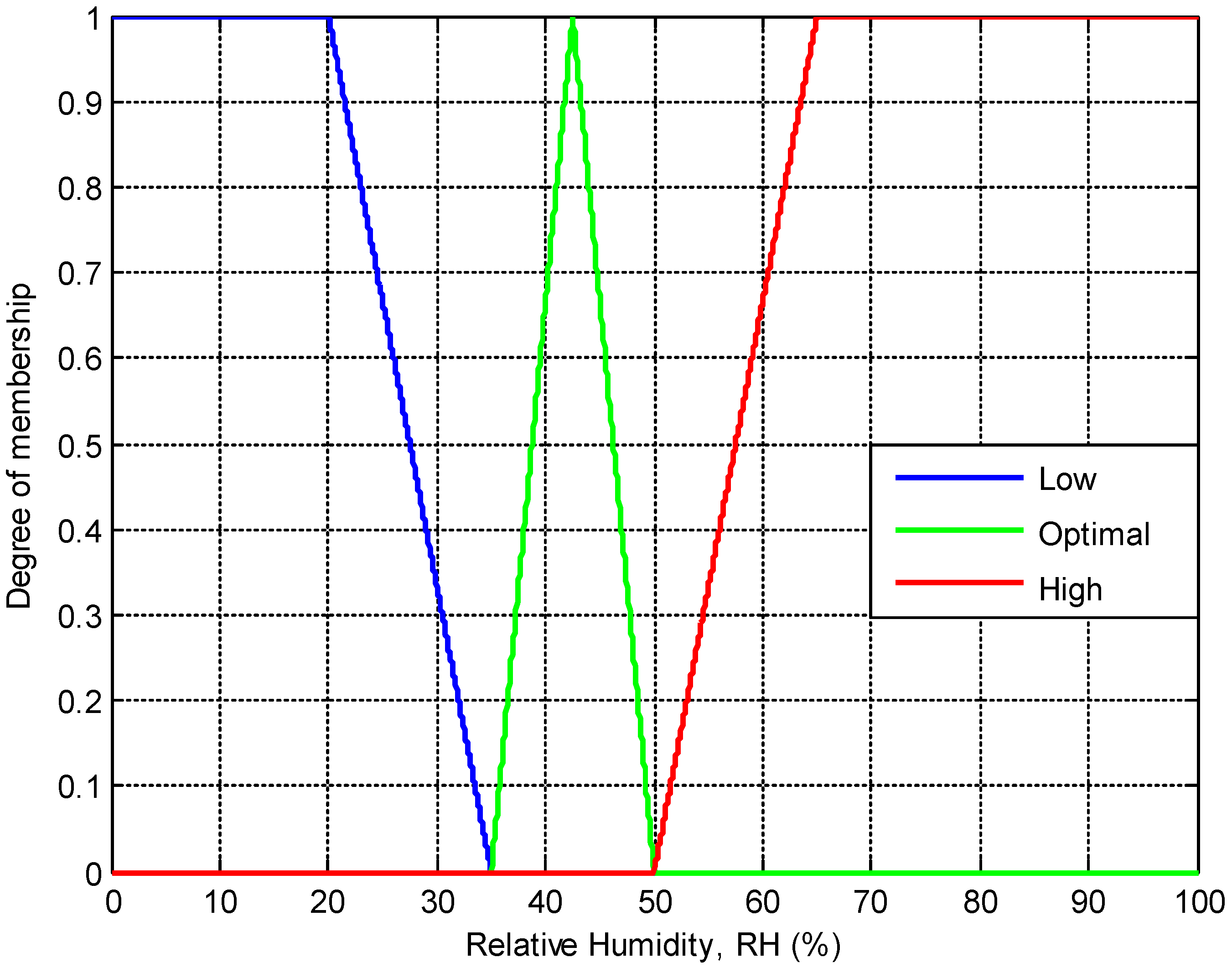

Relative Humidity Membership Functions (with Formulas)

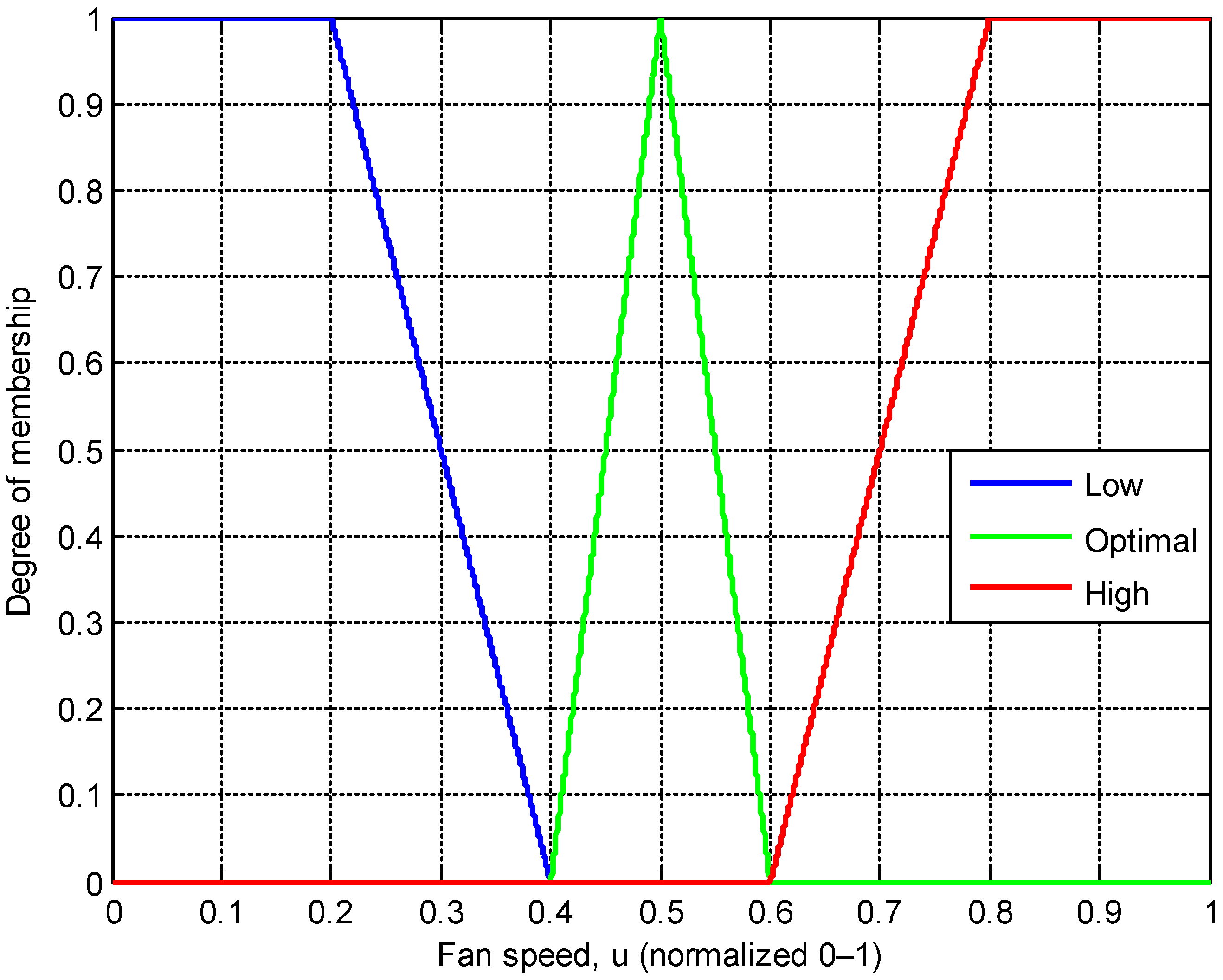

Fan Speed Membership Functions (with Formulas)

2.3.3. Rule Base Construction

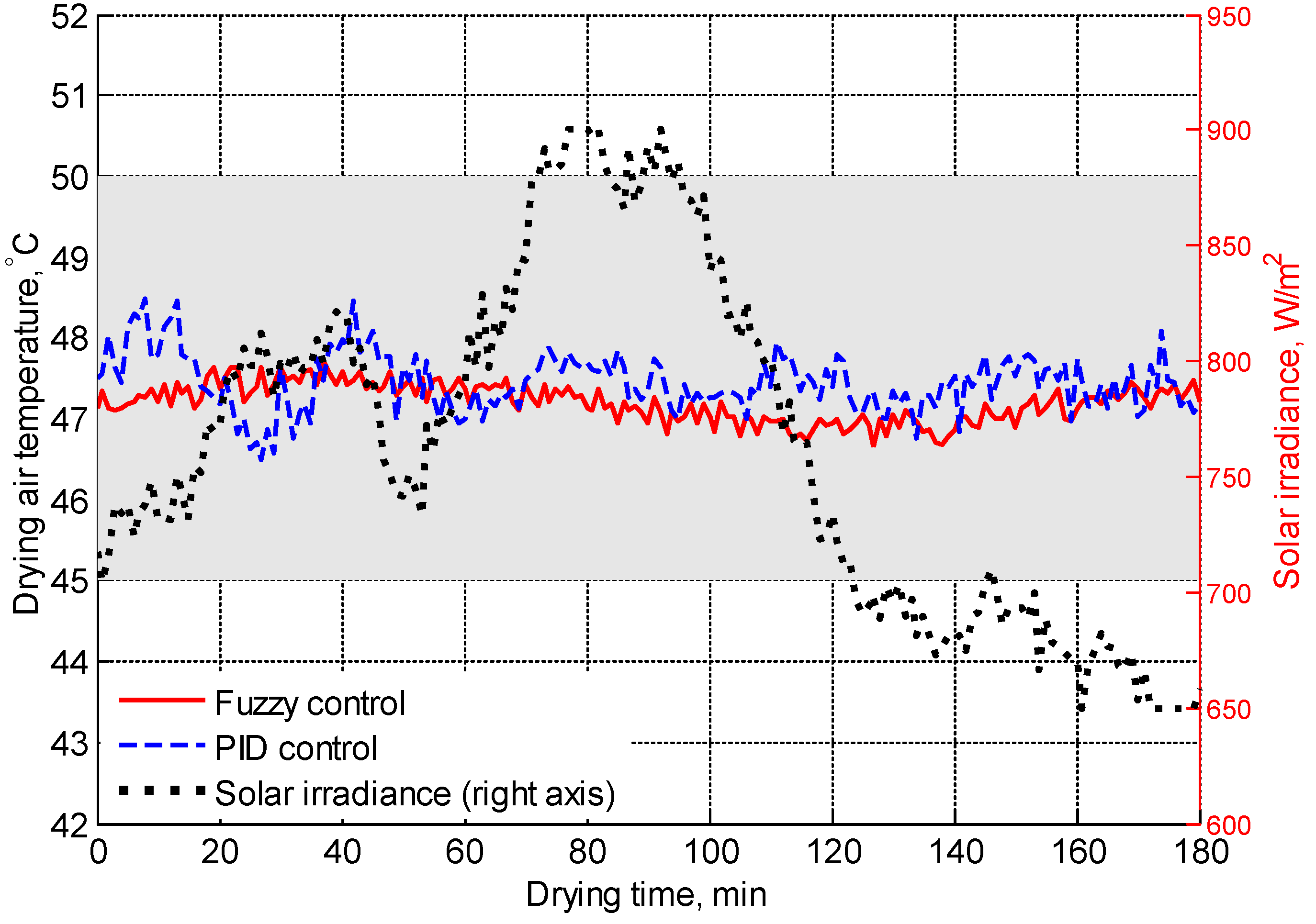

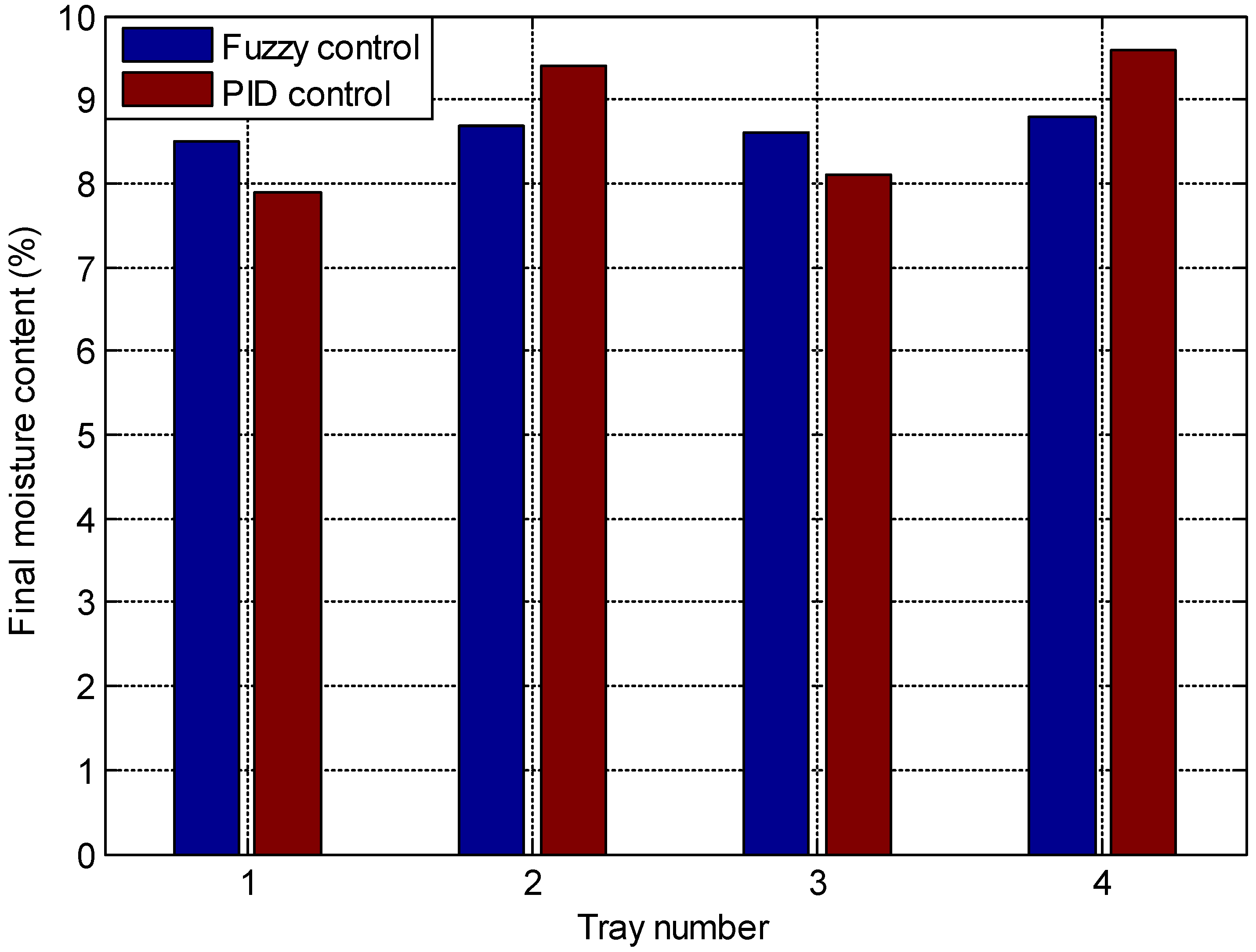

3. Result and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ayadi, M.; Zouari, I.; Bellagi, A. Simulation and Performance of a Solar Drying Unit with Storage for Aromatic and Medicinal Plants. Int. J. Food Eng. 2015, 11, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Heindl, A. Drying of Medicinal Plants. In Medicinal and Aromatic Plants; Bogers, R.J., Craker, L.E., Lange, D., Eds.; Wageningen UR Frontis Series; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 17, pp. 237–252. ISBN 978-1-4020-5447-1. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, O.; Laguri, V.; Pandey, A.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, A. Review on Various Modelling Techniques for the Solar Dryers. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 396–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafian, Y.; Hamedi, S.S.; Kaboli Farshchi, M.; Feyzabadi, Z. Plantago Major in Traditional Persian Medicine and Modern Phytotherapy: A Narrative Review. Electron. Physician 2018, 10, 6390–6399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janjai, S.; Bala, B.K. Solar Drying Technology. Food Eng. Rev. 2012, 4, 16–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakubova, N.; Usmanov, K.; Turakulov, Z.; Eshbobaev, J. Application of Quantum Computing Algorithms in the Synthesis of Control Systems for Dynamic Objects. Eng. Proc. 2025, 87, 68. [Google Scholar]

- Abakarov, A.; Jiménez-Ariza, H.; Correa-Hernando, E.; Diezma, B.; Arranz, F.J.; García, J.; Robla, J.I.; Barreiro, P. Control of a Solar Dryer through Using a Fuzzy Logic and Low-Cost Model-Based Sensor. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Agricultural Engineering, CIGR-Ageng 2012, Valencia, Spain, 8–12 July 2012; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, T.; Sun, D.-W. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD)—An Effective and Efficient Design and Analysis Tool for the Food Industry: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2006, 17, 600–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, Z.; Gokayaz, L.; Köse, E.; Mühürcü, A. Adaptive Neural Network Based Fuzzy Inference System for the Determination of Performance in the Solar Tray Dryer. Eurasian J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 5, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Karaboga, D.; Kaya, E. Adaptive Network Based Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) Training Approaches: A Comprehensive Survey. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2019, 52, 2263–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoukit, A.; El Ferouali, H.; Salhi, İ.; Doubabi, S.; Abdenouri, N. Fuzzy Modeling of a Hybrid Solar Dryer: Experimental Validation. J. Energy Syst. 2019, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez, J.; Reyes, A.; Mahn, A.; Cubillos, F. Experimental Evaluation of Fuzzy Control Solar Drying with Thermal Energy Storage System. Dry. Technol. 2016, 34, 1558–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, J.P.; Rajender, G.; Tejaswi, D.; Nagalaxmi, C.; Suman, D.; Reddy, G.V.; Swetha, B. Development of Cost Effective IoT Based Solar Cabinet Dryer. Int. J. Adv. Biochem. Res. 2025, 9, 848–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khallaf, A.E.-M.; El-Sebaii, A. Review on Drying of the Medicinal Plants (Herbs) Using Solar Energy Applications. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 58, 1411–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, I.; Cipta, D.; Munir, H. Fuzzy Logic Control System Implementation on Solar and Gas Energy Dryers. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Applied Science and Technology on Engineering Science, Samarinda, Indonesia, 20–21 August 2021; SCITEPRESS—Science and Technology Publications: Samarinda, Indonesia, 2021; pp. 638–643. [Google Scholar]

- Sadadou, A.; Hanini, S.; Laidi, M.; Rezrazi, A. ANN-Based Approach to Model MC/DR of Some Fruits under Solar Drying. Kem. ind. 2021, 70, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülçimen, F.; Karakaya, H.; Durmuş, A. An Artificial Neural Network Modeling of Solar Drying of Mint: Energy, Exergy, and Drying Kinetics. Res. Sq. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansor, H.; Noor, S.B.M.; Ahmad, R.K.R.; Taip, F.S.; Lutfy, O.F. Intelligent Control of Grain Drying Process Using Fuzzy Logic Controller. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2010, 8, 145–149. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hamdani, A.; Jayasuriya, H.; Pathare, P.B.; Al-Attabi, Z. Drying Characteristics and Quality Analysis of Medicinal Herbs Dried by an Indirect Solar Dryer. Foods 2022, 11, 4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Situmorang, Z.; Situmorang, J.A. Intelligent Fuzzy Controller for a Solar Energy Wood Dry Kiln Process. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Technology, Informatics, Management, Engineering & Environment (TIME-E), Samosir, Indonesia, 7–9 September 2015; pp. 152–157. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Usmanov, K.; Yakubova, N.; Sultanova, S.; Turakulov, Z. Fuzzy-Logic-Based Intelligent Control of a Cabinet Solar Dryer for Plantago major Leaves Under Real Climatic Conditions in Tashkent. Eng. Proc. 2025, 117, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117035

Usmanov K, Yakubova N, Sultanova S, Turakulov Z. Fuzzy-Logic-Based Intelligent Control of a Cabinet Solar Dryer for Plantago major Leaves Under Real Climatic Conditions in Tashkent. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 117(1):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117035

Chicago/Turabian StyleUsmanov, Komil, Noilakhon Yakubova, Shakhnoza Sultanova, and Zafar Turakulov. 2025. "Fuzzy-Logic-Based Intelligent Control of a Cabinet Solar Dryer for Plantago major Leaves Under Real Climatic Conditions in Tashkent" Engineering Proceedings 117, no. 1: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117035

APA StyleUsmanov, K., Yakubova, N., Sultanova, S., & Turakulov, Z. (2025). Fuzzy-Logic-Based Intelligent Control of a Cabinet Solar Dryer for Plantago major Leaves Under Real Climatic Conditions in Tashkent. Engineering Proceedings, 117(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117035