Impact of Operating Conditions on the Reliability of SRAM-Based Physical Unclonable Functions (PUFs) †

Abstract

1. Introduction

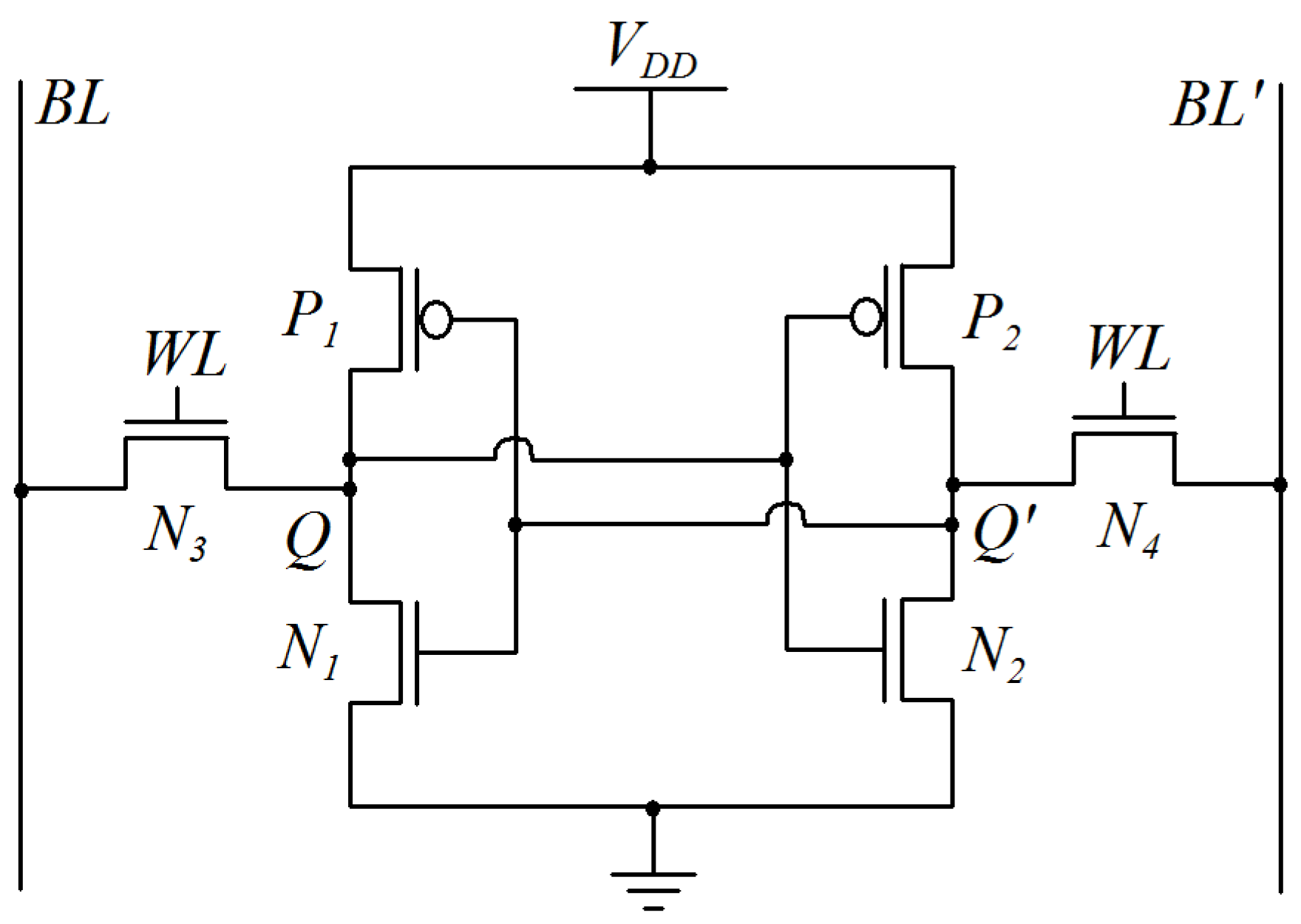

2. SRAM PUF Device

3. Analysis of SRAM Cell Stability

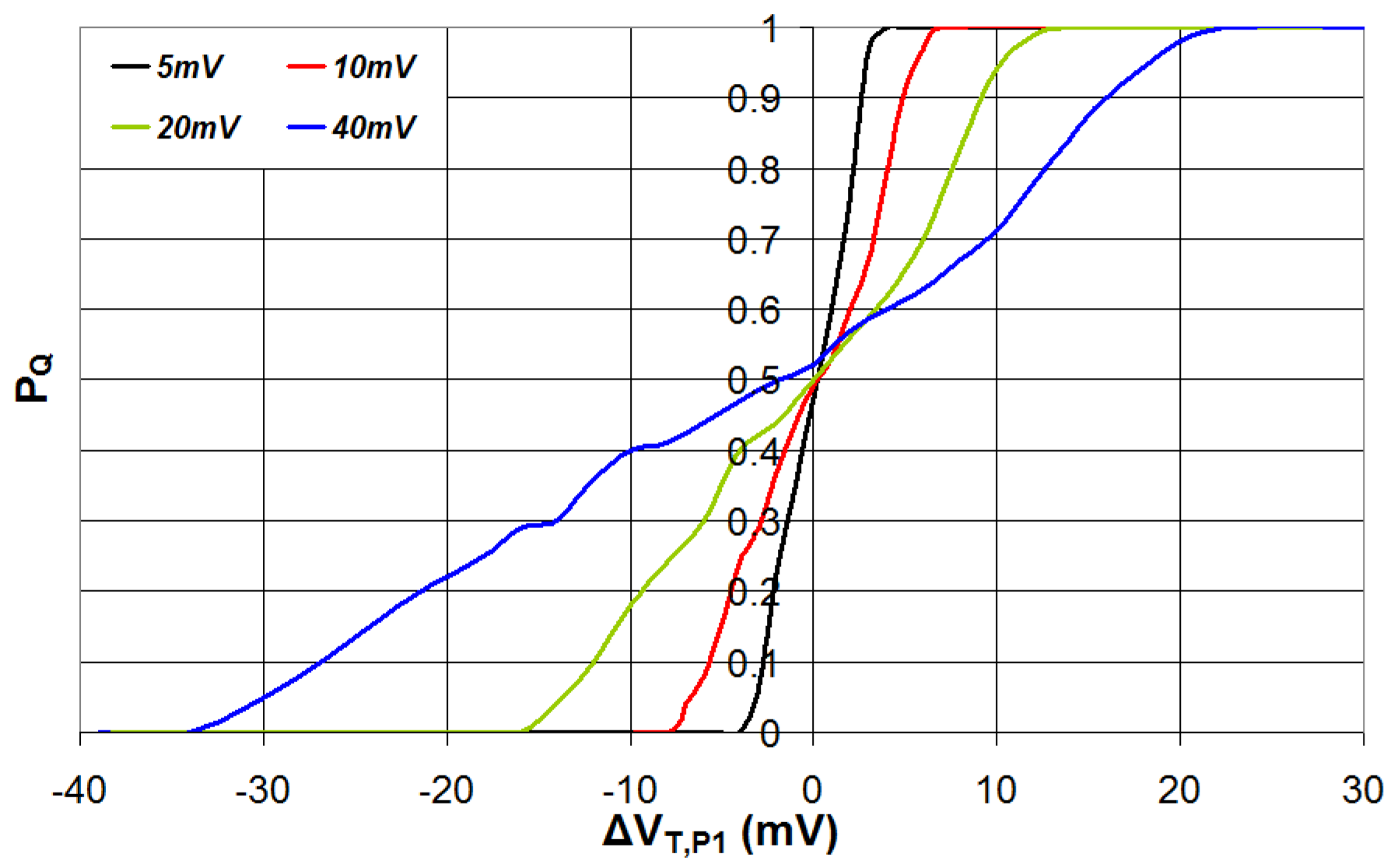

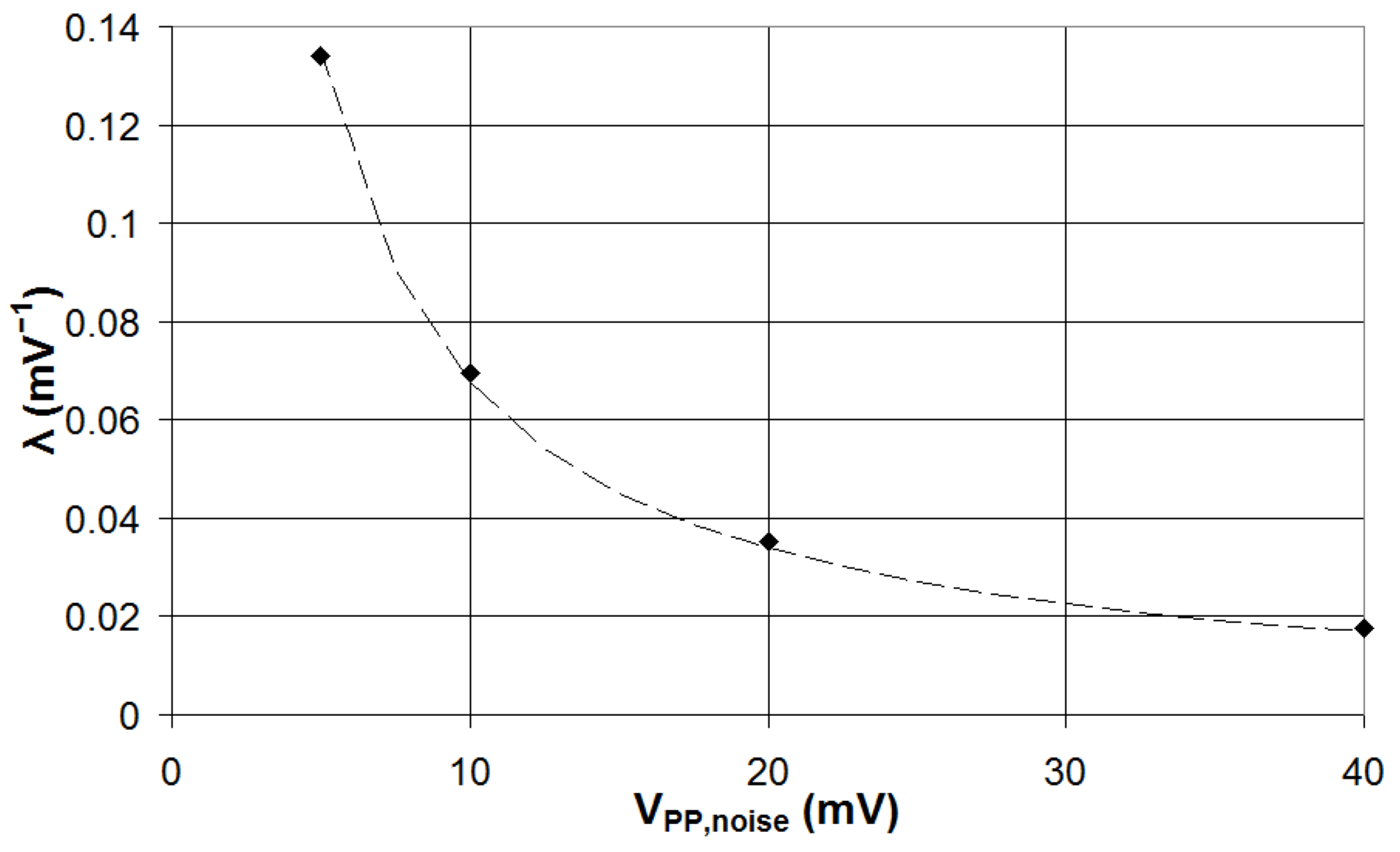

3.1. Impact of the Electrical Noise

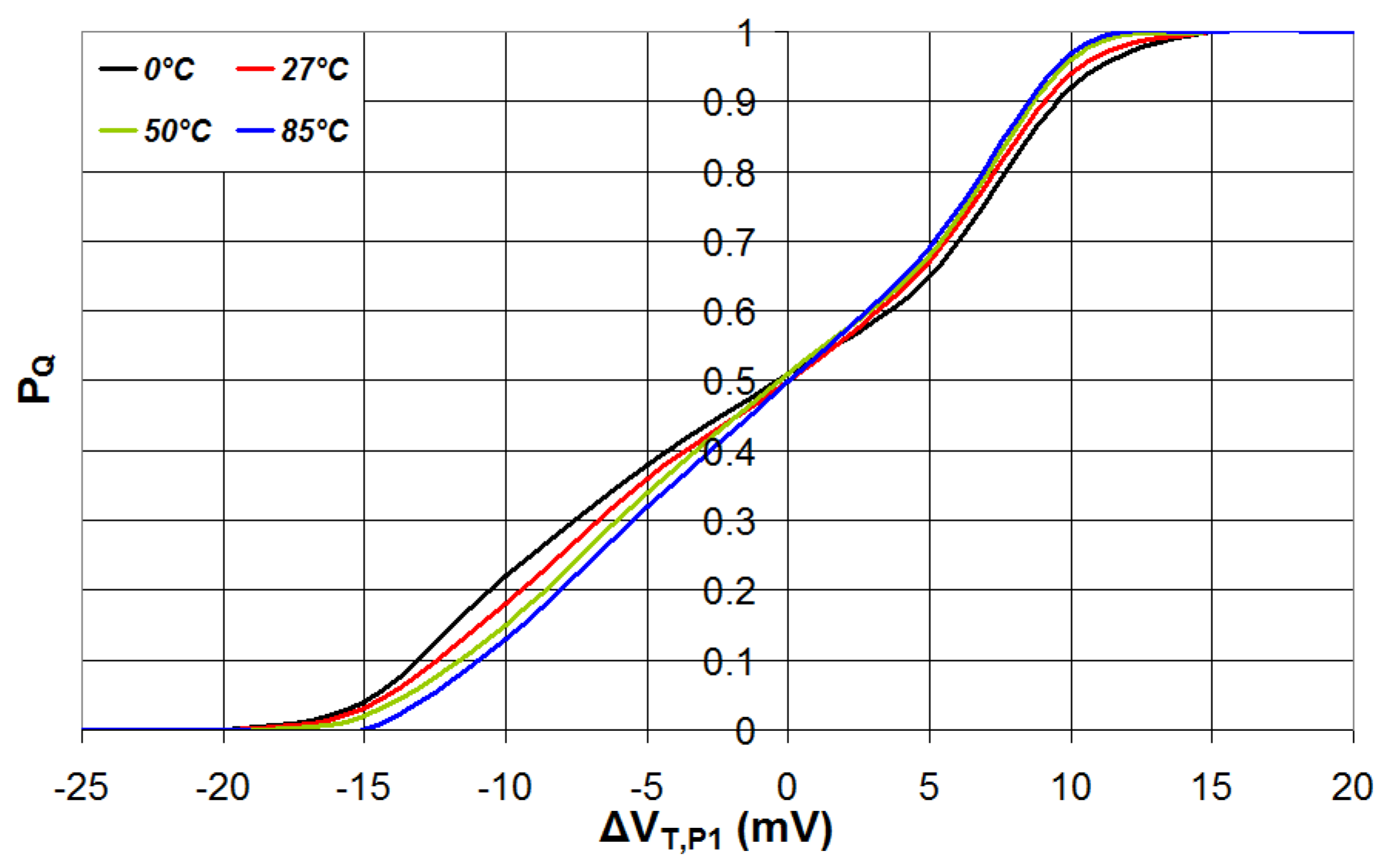

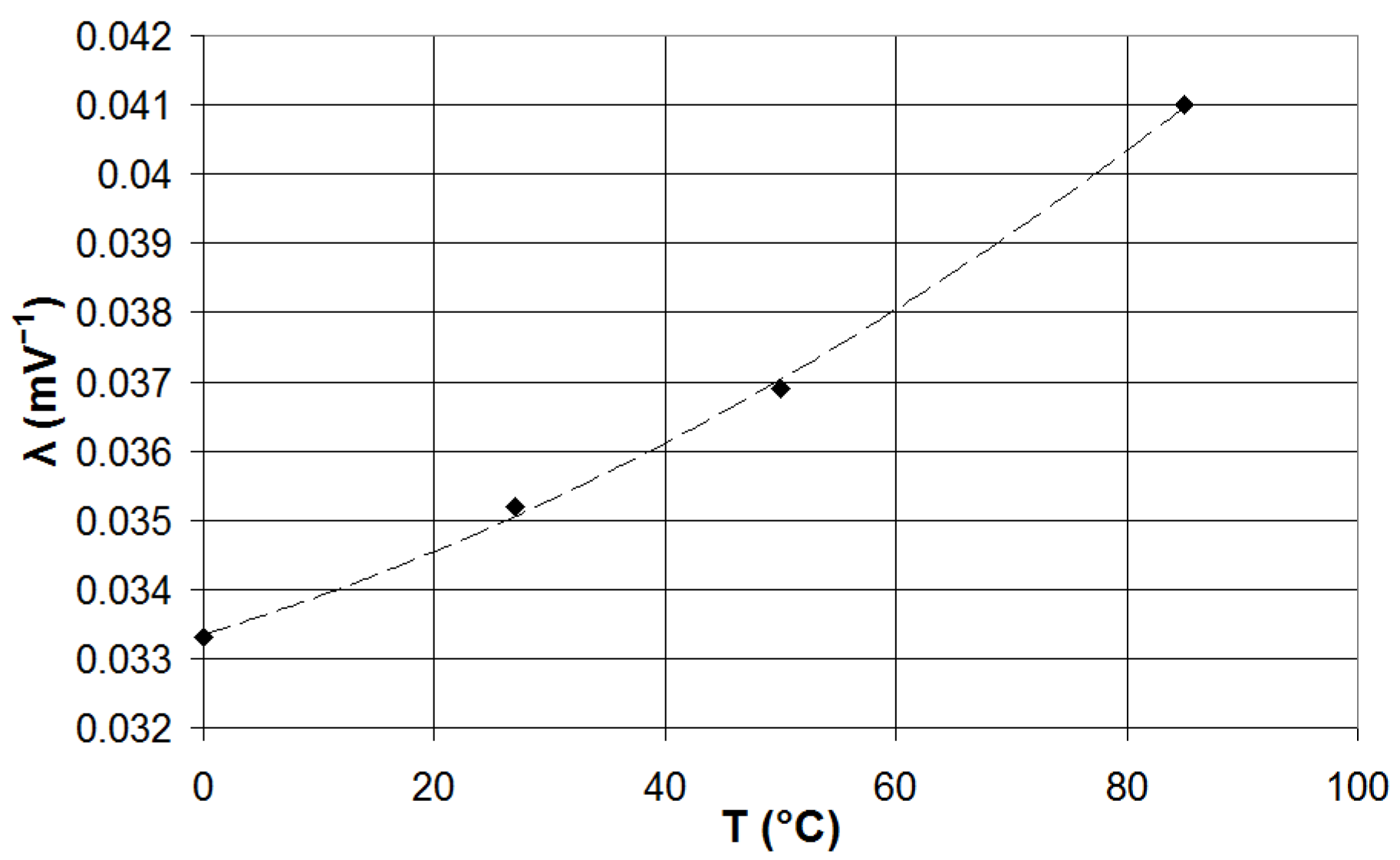

3.2. Impact of Temperature Variations

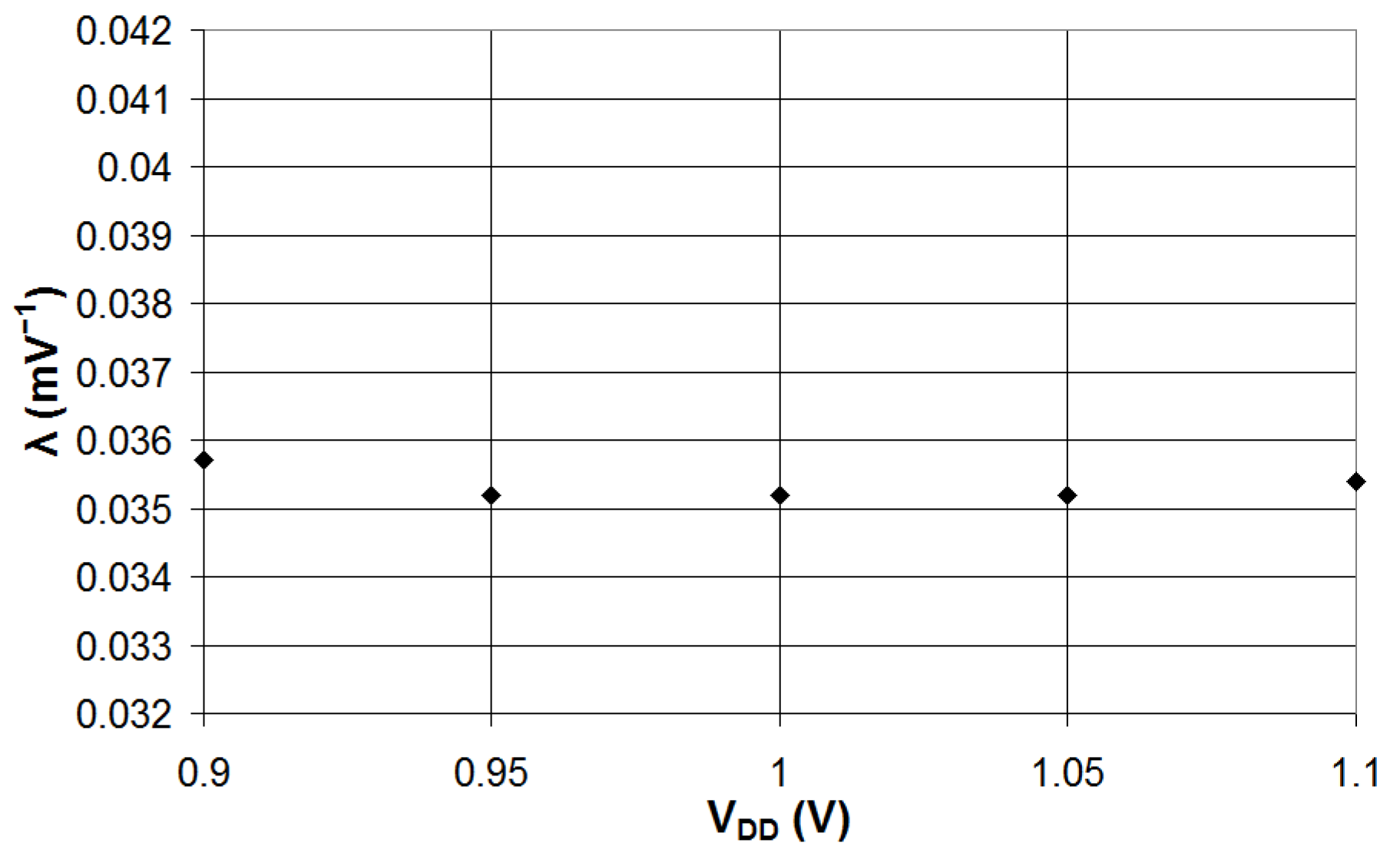

3.3. Impact of Power Supply Voltage Variations

4. Analysis of SRAM-Based PUF Reliability

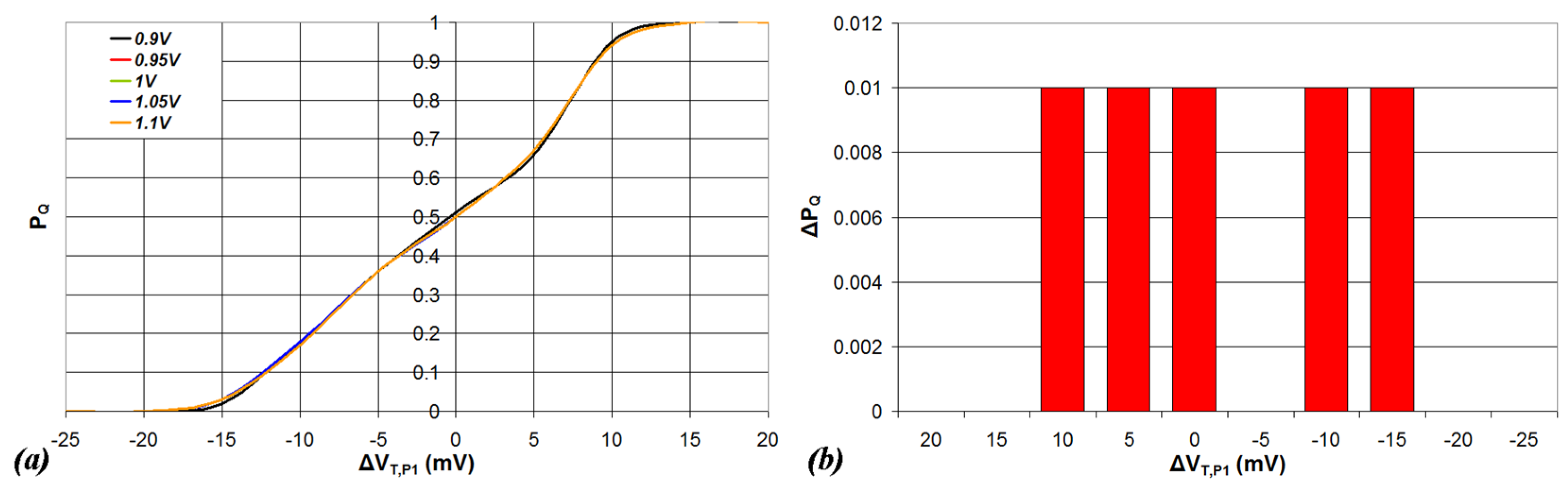

4.1. Impact of Transistor P1 Threshold Voltage Variations

4.2. Impact of Threshold Voltage Variations on All Transistors

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Choudhary, V.; Guha, P.; Pau, G.; Mishra, S. An overview of smart agriculture using internet of things (IoT) and web services. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 26, 100607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.N.; Rahman, M.M.; Billah, M.M.; Saha, D. Internet of things (IoT): A review of its enabling technologies in healthcare applications, standards protocols, security, and market opportunities. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 10474–10498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshed, M.A.; Ali, K.; Abbasi, Q.H.; Imran, M.A.; Ur-Rehman, M. Challenges, applications, and future of wireless sensors in Internet of Things: A review. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 5482–5494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, M.; Valli, E.; Glicerina, V.T.; Rocculi, P.; Toschi, T.G.; Riccò, B. Optical determination of solid fat content in fats and oils: Effects of wavelength on estimated accuracy. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2022, 124, 2100071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.N.; Akram, M.M.; Das, P.S.; Lazarjan, V.K.; Tremblay, D.M.; Moineau, S.; Messaddeq, Y.; Gosselin, B. Multimodal CMOS Biosensor for Microbial Growth Monitoring. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 14670–14684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela, L.M.; Kwon, H.; Rutkove, S.B.; Sanchez, B. Standalone IoT bioimpedance device supporting real-time online data access. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 9545–9554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Wu, F.; Han, W.; Yuce, M.R. A wearable bioimpedance chest patch for real-time ambulatory respiratory monitoring. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 69, 2970–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossi, M.; Alfonsi, F.; Prandini, M.; Gabrielli, A. Increasing the Security of Network Data Transmission with a Configurable Hardware Firewall Based on Field Programmable Gate Arrays. Future Internet 2024, 16, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fan, Y.; Bian, X.; Yuan, Q. Online/offline MA-CP-ABE with cryptographic reverse firewalls for IoT. Entropy 2023, 25, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sha, K.; Yang, T.A.; Wei, W.; Davari, S. A survey of edge computing-based designs for IoT security. Digit. Commun. Netw. 2020, 6, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, M.; Alfonsi, F.; Prandini, M.; Gabrielli, A. A Highly Configurable Packet Sniffer Based on Field-Programmable Gate Arrays for Network Security Applications. Electronics 2023, 12, 4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Yu, S.; Lee, J.; Son, S.; Kim, M.; Park, Y. A secure and lightweight authentication protocol for IoT-based smart homes. Sensors 2021, 21, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqib, M.; Jasra, B.; Moon, A.H. A lightweight three factor authentication framework for IoT based critical applications. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34, 6925–6937. [Google Scholar]

- Thakor, V.A.; Razzaque, M.A.; Khandaker, M.R. Lightweight cryptography algorithms for resource-constrained IoT devices: A review, comparison and research opportunities. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 28177–28193. [Google Scholar]

- Fotovvat, A.; Rahman, G.M.; Vedaei, S.S.; Wahid, K.A. Comparative performance analysis of lightweight cryptography algorithms for IoT sensor nodes. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 8, 8279–8290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Al-Sarawi, S.F.; Abbott, D. Physical unclonable functions. Nat. Electron. 2020, 3, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemavathy, S.; Bhaaskaran, V.K. Arbiter puf—A review of design, composition, and security aspects. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 33979–34004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Chen, W.; Zhang, L.; Chi, G.; Gao, Q.; Harn, L. A highly reliable arbiter PUF with improved uniqueness in FPGA implementation using bit-self-test. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 181751–181762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omaña, M.; Grossi, M.; Rossi, D.; Metra, C. Aging resilient ring oscillators for reliable Physically Unclonable Functions (PUFs). Microelectron. Reliab. 2024, 162, 115520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D.; Hou, S.; Wang, Z.; Guo, Y. Configurable ring oscillator PUF using hybrid logic gates. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 161427–161437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.; Yu, G.H.; Kim, J.; Ngo, C.T.; Eshraghian, J.K.; Hong, J.P. A reconfigurable SRAM based CMOS PUF with challenge to response pairs. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 79947–79960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Kim, T.T.H. A high reliable SRAM-based PUF with enhanced challenge-response space. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2021, 69, 589–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, M.; Omaña, M.; Acquaviva, C.M.A. Novel Physical Unclonable Function Implementation for Microcontrollers and Field Programmable Gate Arrays. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 55970–55983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, M.; Omaña, M. Feasibility of Physical Unclonable Function (PUF) implementation using the pull-up/pull-down resistances integrated in microcontrollers GPIO. AEU-Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2025, 202, 156053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbareschi, M.; Cirillo, F.; Esposito, C. SRAM-PUF Authentication Schemes Empowered with Blockchain on Resource-Constrained Microcontrollers. In Proceedings of the IEEE 27th International Symposium on Real-Time Distributed Computing (ISORC), Tunis, Tunisia, 22–25 May 2024; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Baturone, I.; Prada-Delgado, M.A.; Eiroa, S. Improved generation of identifiers, secret keys, and random numbers from SRAMs. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2015, 10, 2653–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.; Shifman, Y.; Weizman, Y.; Keren, O.; Shor, J. A highly reliable SRAM PUF with a capacitive preselection mechanism and pre-ECC BER of 7.4 E-10. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Custom Integrated Circuits Conference (CICC), Austin, TX, USA, 14–17 April 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Cortez, M.; Dargar, A.; Hamdioui, S.; Schrijen, G.J. Modeling SRAM start-up behavior for physical unclonable functions. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Symposium on Defect and Fault Tolerance in VLSI and Nanotechnology Systems (DFT), Austin, TX, USA, 3–5 October 2012; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Golanbari, M.S.; Kiamehr, S.; Bishnoi, R.; Tahoori, M.B. Reliable memory PUF design for low-power applications. In Proceedings of the 19th International Symposium on Quality Electronic Design (ISQED), Santa Clara, CA, USA, 13–14 March 2018; pp. 207–213. [Google Scholar]

- Holcomb, D.E.; Burleson, W.P.; Fu, K. Power-up SRAM state as an identifying fingerprint and source of true random numbers. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2008, 58, 1198–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, R.; Van Der Leest, V. Countering the effects of silicon aging on SRAM PUFs. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International symposium on hardware-oriented security and trust (HOST), Arlington, VA, USA, 6–7 May 2014; pp. 148–153. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatta, N.P.; Singh, H.; Ghimire, A.; Amsaad, F. Analyzing aging effects on SRAM PUFs: Implications for security and reliability. J. Hardw. Syst. Secur. 2024, 8, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alheyasat, A.; Torrens, G.; Bota, S.; Alorda, B. Selection of SRAM cells to improve reliable PUF implementation using cell mismatch metric. In Proceedings of the IEEE XXXV Conference on Design of Circuits and Integrated Systems (DCIS), Segovia, Spain, 18–20 November 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mathew, S.K.; Satpathy, S.K.; Anders, M.A.; Kaul, H.; Hsu, S.K.; Agarwal, A.; Chen, G.K.; Parker, R.J.; Krishnamurthy, R.K.; De, V. A 0.19 pJ/b PVT-variation-tolerant hybrid physically unclonable function circuit for 100% stable secure key generation in 22nm CMOS. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference Digest of Technical Papers (ISSCC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 9–13 February 2014; pp. 278–279. [Google Scholar]

- LTSpice Simulator. Available online: https://www.analog.com/en/resources/design-tools-and-calculators/ltspice-simulator.html (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Maiti, A.; Gunreddy, V.; Schaumont, P. A systematic method to evaluate and compare the performance of physical unclonable functions. In Embedded Systems Design with FPGAs; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 245–267. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Grossi, M.; Omaña, M.; Bisi, S.; Metra, C.; Acquaviva, A. Impact of Operating Conditions on the Reliability of SRAM-Based Physical Unclonable Functions (PUFs). Eng. Proc. 2026, 124, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2026124010

Grossi M, Omaña M, Bisi S, Metra C, Acquaviva A. Impact of Operating Conditions on the Reliability of SRAM-Based Physical Unclonable Functions (PUFs). Engineering Proceedings. 2026; 124(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2026124010

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrossi, Marco, Martin Omaña, Simone Bisi, Cecilia Metra, and Andrea Acquaviva. 2026. "Impact of Operating Conditions on the Reliability of SRAM-Based Physical Unclonable Functions (PUFs)" Engineering Proceedings 124, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2026124010

APA StyleGrossi, M., Omaña, M., Bisi, S., Metra, C., & Acquaviva, A. (2026). Impact of Operating Conditions on the Reliability of SRAM-Based Physical Unclonable Functions (PUFs). Engineering Proceedings, 124(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2026124010