A Novel Circular Waste-to-Energy Pathway via Cascading Valorization of Spent Coffee Grounds Through Non-Catalytic Supercritical Transesterification of Pyrolytic Oil for Liquid Hydrocarbon †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

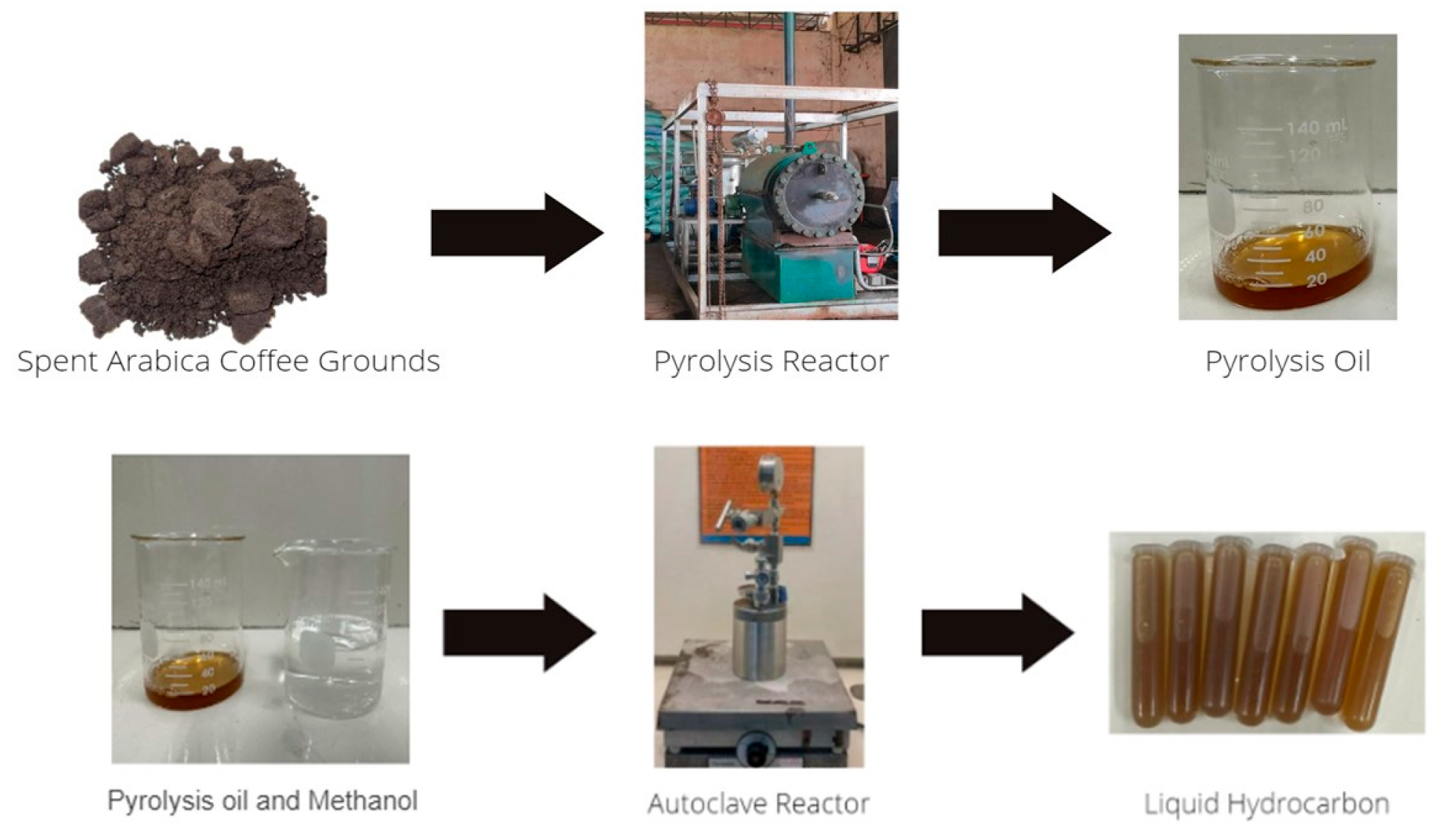

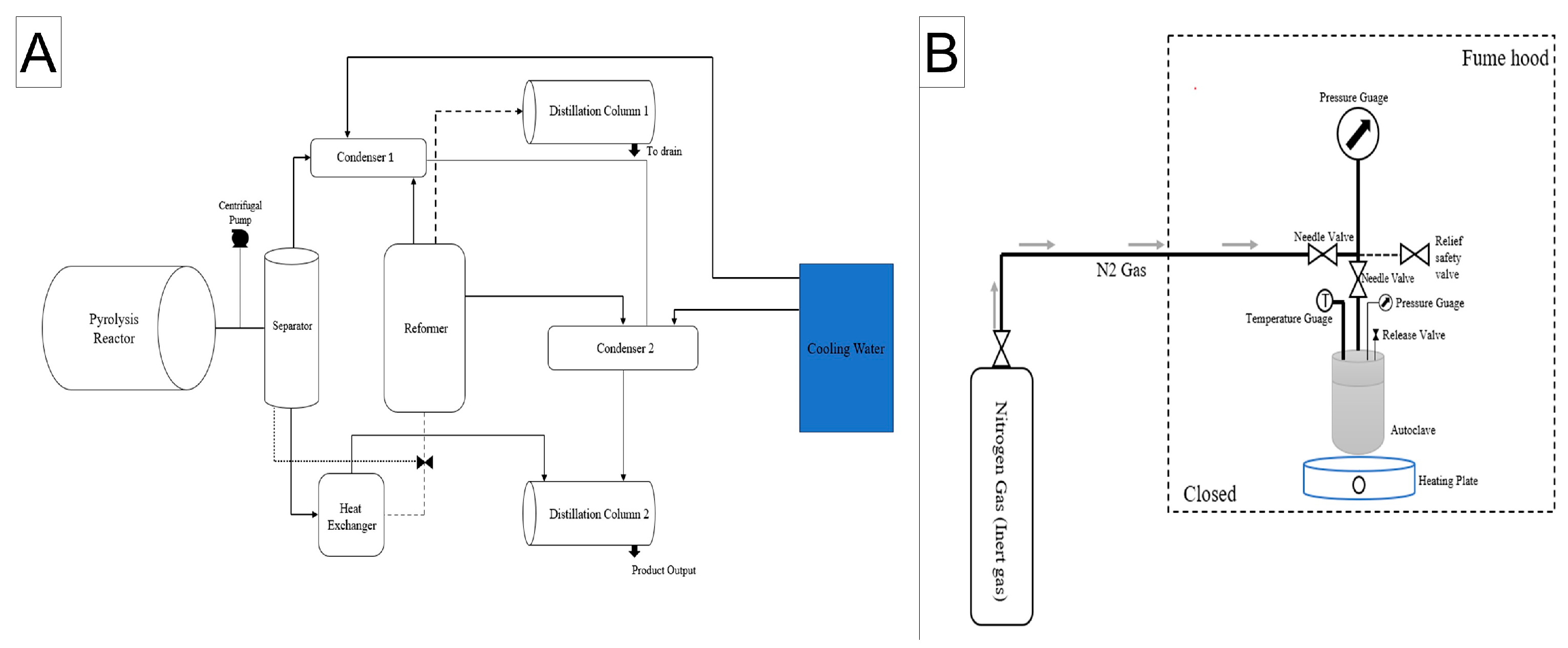

2.2. Pyrolysis Oil Extraction

2.3. Product Analysis and Statistical Treatment

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Pyrolytic Oil Recovery from SCG

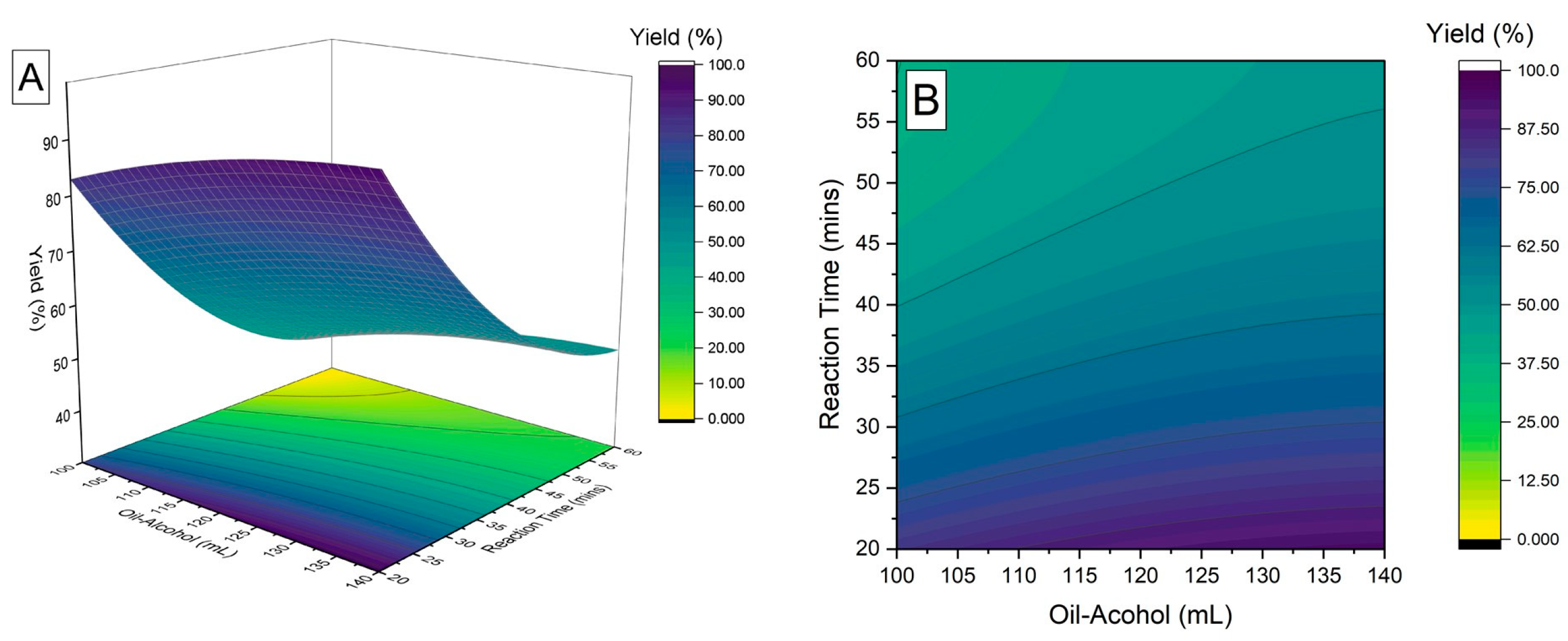

3.2. Optimization of Liquid Hydrocarbon Yield via Non-Catalytic Supercritical Transesterification

3.3. Physicochemical Characterization of the Produced Liquid Hydrocarbons

3.4. Mechanistic Insights into Non-Catalytic Supercritical Transesterification

3.5. Evaluation of the Cascading Valorization Approach for SCG Utilization

3.6. Advancing Circularity in Waste Management and the Broader Implications of SCG Valorization

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Latiza, R.J.P.; Rubi, R.V. Circular Economy Integration in 1G + 2G Sugarcane Bioethanol Production: Application of Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage, Closed-Loop Systems, and Waste Valorization for Sustainability. Appl. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2025, 18, 7448. [Google Scholar]

- Milanković, V.; Tasić, T.; Pašti, I.A.; Lazarević-Pašti, T. Resolving Coffee Waste and Water Pollution—A Study on KOH-Activated Coffee Grounds for Organophosphorus Xenobiotics Remediation. J. Xenobiotics 2024, 14, 1238–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, H.; Lee, M.; Choi, J.; Oh, S. Effect of Temperature and Heating Rate on Pyrolysis Characteristics of Spent Coffee Grounds. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 42, 2853–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, B.O.; Oladepo, S.A.; Ganiyu, S.A. Efficient and Sustainable Biodiesel Production via Transesterification: Catalysts and Operating Conditions. Catalysts 2024, 14, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, I.A. The effects of alcohol to oil molar ratios and the type of alcohol on biodiesel production using transesterification process. Egypt. J. Pet. 2016, 25, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marulanda, V.F. Biodiesel production by supercritical methanol transesterification: Process simulation and potential environmental impact assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 33, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceran, Z.D.; Demir, V.; Akgün, M. Optimization and kinetic study of biodiesel production from Jatropha curcas oil in supercritical methanol environment using ZnO/γ-Al2O3 catalyst. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 15, 3903–3914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vibhakar, C.; Sabeenian, R.S.; Kaliappan, S.; Patil, P.Y.; Patil, P.P.; Madhu, P.; Dhanalakshmi, C.S.; Birhanu, H.A. Production and Optimization of Energy Rich Biofuel through Co-Pyrolysis by Utilizing Mixed Agricultural Residues and Mixed Waste Plastics. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, 8175552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwao-Boateng, E.; Ankudey, E.G.; Darkwah, L.; Danquah, K.O. Assessment of Diesel Fuel Quality. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atabani, A.; Ali, I.; Naqvi, S.R.; Badruddin, I.A.; Aslam, M.; Mahmoud, E.; Almomani, F.; Juchelková, D.; Atelge, M.; Khan, T.Y. A state-of-the-art review on spent coffee ground (SCG) pyrolysis for future biorefinery. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Zhang, L.; Dong, Z.; Ming, H.; Xiao, Y.; Fan, Q.; Yang, C.; Cheng, L. Co-hydrothermal conversion of kitchen waste and agricultural solid waste biomass components by simple mixture: Study based on bio-oil yield and composition. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2024, 180, 106557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Wu, S.; Chen, J.; Zhou, X.; Chen, X.; Xin, Z.; Ding, P.; Xiao, R. Toward Efficient Biofuel Production: A Review of Online Upgrading Methods for Biomass Pyrolysis. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 19414–19441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Z.; Bustam, M.A.; Ullah, M.; Rashid, M.U.; Khan, A.S.; Shah, S.N.; Shah, M.U.H.; Ahmad, P.; Sohail, M.; Khan, K.A. Unveiling Biodiesel Production: Exploring Reaction Protocols, Catalysts, and Influential Factors. ChemBioEng Rev. 2024, 11, e202400028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Peng, W.; Zeng, X.; Sun, D.; Cui, G.; Han, Z.; Wang, C.; Xu, G. Insight into staged gasification of biomass waste: Essential fundamentals and applications. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 953, 175954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faizi, M.K.; Shahriman, A.B.; Majid, M.S.A.; Rahman, M.N.M.A.; Shamsul, B.M.T.; Ng, Y.G.; Razlan, Z.M.; Wan, W.K.; Hashim, M.S.M.; Rojan, M.A. The Physical Properties Observation of Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunch (OPEFB) Chemical Treated Fibres. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 670, 012055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, L.F.; Klemeš, J.J.; Yusup, S.; Bokhari, A.; Akbar, M.M.; Chong, Z.K. Kinetic Studies on Waste Cooking Oil into Biodiesel via Hydrodynamic Cavitation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 146, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Feng, X.; Tao, G.; Guo, R.; Xu, J. Flammability limits of methanol/methacrolein mixed vapor under elevated temperatures and pressures. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2024, 90, 105342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardon, D.R.; Moser, B.R.; Zheng, W.; Witkin, K.; Evangelista, R.L.; Strathmann, T.J.; Rajagopalan, K.; Sharma, B.K. Complete utilization of spent coffee grounds to produce biodiesel, bio-oil, and biochar. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2013, 1, 1286–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilham, Z.; Saka, S. Dimethyl carbonate as potential reactant in non-catalytic biodiesel production by supercritical method. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 1793–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glisic, S.B.; Orlovic, A.M. Review of biodiesel synthesis from waste oil under elevated pressure and temperature: Phase equilibrium, reaction kinetics, process design and techno-economic study. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 31, 708–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, I.; Argenziano, R.; Borselleca, E.; Moccia, F.; Panzella, L.; Pezzella, C. Cascade disassembling of spent coffee grounds into phenols, lignin and fermentable sugars en route to a green active packaging. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 334, 125998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iakovou, G.; Ipsakis, D.; Triantafyllidis, K.S. Kraft lignin fast (catalytic) pyrolysis for the production of high value-added chemicals (HVACs): A techno-economic screening of valorization pathways. Environ. Res. 2024, 248, 118205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, H.; Abolore, R.S.; Jaiswal, S.; Jaiswal, A.K. Toward Circular Economy: Potentials of Spent Coffee Grounds in Bioproducts and Chemical Production. Biomass 2024, 4, 286–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusufoğlu, B.; Kezer, G.; Wang, Y.; Ziora, Z.M.; Esatbeyoglu, T. Bio-recycling of spent coffee grounds: Recent advances and potential applications. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2024, 55, 101111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latiza, R.J.P.; Mustafa, A.; Reyes, K.D.; Nebres, K.L.; Abrogena, S.L.; Rubi, R.V. Optimization, characterization, reversible thermodynamically favored adsorption, and mechanistic insights into low-cost mesoporous Fe-doped kapok fibers for efficient caffeine removal from water. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2025, 60, 1643–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latiza, R.J.P.; Olay, J.; Eguico, C.; Yan, R.J.; Rubi, R.V. Environmental applications of carbon dots: Addressing microplastics, air and water pollution. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 17, 100591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saka, S.; Kusdiana, D. Biodiesel fuel from rapeseed oil as prepared in supercritical methanol. Fuel 2001, 80, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Oil to Alcohol Ratio | Reaction Time (mins) | Accumulated Liquid Hydrocarbon (mL) | Liquid Hydrocarbon Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1:5 | 40 | 72 | 60.0 |

| 1:4 | 60 | 37 | 37.0 |

| 1:6 | 40 | 83.3 | 59.5 |

| 1:5 | 60 | 54 | 45.0 |

| 1:5 | 20 | 108 | 90.0 |

| 1:6 | 60 | 70 | 50.0 |

| 1:6 | 20 | 134.4 | 96.0 |

| 1:4 | 20 | 83 | 83.0 |

| 1:4 | 40 | 50 | 50.0 |

| ANOVA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | DF | Adj SS | Adj MS | F-Value | p-Value |

| Model | 5 | 3563.44 | 712.69 | 171.81 | 0.001 |

| Linear | 2 | 3338.21 | 1669.1 | 402.37 | 0 |

| A | 1 | 210.04 | 210.04 | 50.64 | 0.006 |

| B | 1 | 3128.17 | 3128.17 | 754.11 | 0 |

| Square | 2 | 225.24 | 112.62 | 27.15 | 0.012 |

| A2 | 1 | 11.68 | 11.68 | 2.82 | 0.192 |

| B2 | 1 | 213.56 | 213.56 | 51.48 | 0.006 |

| Interaction | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| AB | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Error | 3 | 12.44 | 4.15 | ||

| Total | 8 | 3575.89 | |||

| Model Summary | |||||

| S | R-sq | R-sq (adj) | R-sq (pred) | ||

| 2.0367 | 99.65% | 99.07% | 96.82% | ||

| Optimal Solution | |||||

| Oil to alcohol ratio | Time (mins) | Yield (%) | Desirability | ||

| 1:6 | 20 | 96 | 0.979284 | ||

| Properties | Testing Protocols | Standard | SCG |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density at 15 °C | ASTM D4052 | 0.86 g/cm3 | 0.7557 g/cm3 |

| Viscosity at 40 °C | ASTM D445 | 2.48 cSt | 0.7297 cSt |

| Flashpoint | ASTM D93 | 35 °C | 32 °C |

| Cetane Index | ASTM D976 | 40 | 28.2 |

| Low Heating Value | ASTM D4868 | 38.80 Mj/kg | 43.77 MJ/kg |

| High Heating Value | ASTM D4868 | 44.80 Mj/kg | 46.86 MJ/kg |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bantilan, E.J.; Batistil, J.; Calcabin, B.A.; Organo, E.; Ramirez, N.M.; Binay, J.; Raguindin, R.; Rubi, R.V.; Latiza, R.J.P. A Novel Circular Waste-to-Energy Pathway via Cascading Valorization of Spent Coffee Grounds Through Non-Catalytic Supercritical Transesterification of Pyrolytic Oil for Liquid Hydrocarbon. Eng. Proc. 2025, 117, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117016

Bantilan EJ, Batistil J, Calcabin BA, Organo E, Ramirez NM, Binay J, Raguindin R, Rubi RV, Latiza RJP. A Novel Circular Waste-to-Energy Pathway via Cascading Valorization of Spent Coffee Grounds Through Non-Catalytic Supercritical Transesterification of Pyrolytic Oil for Liquid Hydrocarbon. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 117(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117016

Chicago/Turabian StyleBantilan, Elmer Jann, Joana Batistil, Bernice Ann Calcabin, Ephriem Organo, Neome Mitzi Ramirez, Jayson Binay, Reibelle Raguindin, Rugi Vicente Rubi, and Rich Jhon Paul Latiza. 2025. "A Novel Circular Waste-to-Energy Pathway via Cascading Valorization of Spent Coffee Grounds Through Non-Catalytic Supercritical Transesterification of Pyrolytic Oil for Liquid Hydrocarbon" Engineering Proceedings 117, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117016

APA StyleBantilan, E. J., Batistil, J., Calcabin, B. A., Organo, E., Ramirez, N. M., Binay, J., Raguindin, R., Rubi, R. V., & Latiza, R. J. P. (2025). A Novel Circular Waste-to-Energy Pathway via Cascading Valorization of Spent Coffee Grounds Through Non-Catalytic Supercritical Transesterification of Pyrolytic Oil for Liquid Hydrocarbon. Engineering Proceedings, 117(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025117016