1. Introduction

The performance and fuel consumption of spark ignition engines are inextricably correlated to the design of the exhaust system. This is because the exit of gases from the cylinders is highly affected by the flow within the exhaust system, particularly by back pressure generation [

1]. Briefly described, the exhaust back pressure is determined as the variation between atmospheric pressure and exhaust pressure and basically affects the flow of combustion gases. A lot of studies employ numerical means as tools for optimizing the exhaust system. Mylaudy et al. [

2] conducted a numerical study on the optimization of a spark-ignition muffler to achieve lower fuel consumption. Their mathematical-based approach for muffler design optimization indicated that fuel consumption increases exponentially with increasing exhaust back pressure [

2]. A significant notice is that the limit of back pressure is affected by the charging system of the engine (i.e., normally aspirated or turbocharged) [

3]. Interesting information is provided by P. Srinivas et al. In their study, they refer that the maximum recommended back pressure is 40, 20, and 10 kPa for engines that exhibit 50, 50–500, and over 500 hp, respectively [

3]. A short conclusion of the above is that at low to mid-range engine speeds, the observations are well-understood and coincide with many other research studies listed in the IC engines’ literature. At this point, it has to be stated that the induction and exhaust processes in internal combustion engines are not simple. The flow that is generated by the upward movement of the piston (Bottom Dead Center to Top Dead Center) within the cylinders during the exhaust process (Exhaust Valve open), pushes the combustion gases out of the cylinder. In typical Spark Ignition (SI) engines, slightly before the piston reaches Top Dead Center, the Intake valves begin to open. The flow of gases exiting the exhaust ports and the opening of the intake valves assist the induction of the fresh air–fuel mixture. The short time during which exhaust and intake valves are open is called the overlapping period. And it starts 10 to 30° before the TDC (Top Dead Center) and finishes 10 to 30° after the TDC, depending on the type of engine. This short period of time is crucial for the volumetric efficiency of the engine, which plays a vital role in fuel consumption and in power. The peripheral components (exhaust system and intake system) of SI ICE have to be designed in such a way that this short period of time will play a significant role in the maximum efficiency of the engine [

4]. The latter is correlated to the fact that if the back pressure in exhaust increases by a certain amount of ΔPexhaust, the pressure in the intake manifold has to rise by ΔPintake in order to maintain the same amount of Indicated Mean Effective Pressure (IMEP) within the cylinder [

5,

6].

Summarizing all the above, the optimum scenario is to maintain the IMEP as high as possible to satisfy the requirement for high volumetric efficiency across the entire engine speed range, thereby attaining the highest possible power output with the least fuel consumption. This scenario is very hard to achieve since the flow of air and combustion gases is a complicated function of many parameters (engine speed, geometries of exhaust, intake, and cylinder head systems, intake system conditions, valves overlapping period, and generally the fluid dynamic conditions of the domains).

2. Modeling of the Exhaust System

The efficiency of an engine is either associated with fuel consumption or the power output is inextricably correlated to the design of the exhaust system. The latter affects the volumetric filling of cylinders with adequate quantities of combustible air–fuel mixture. The highest is the filling of the cylinders, and the highest is the power output/torque during the combustion process. An additional point that was investigated was the effect of exhaust design on the mixing process and thus, of the homogeneity of the combustible mixture within the cylinders. The homogeneity affects not only the performance, but also the amount of the undesirable combustion products.

At the moment, the authors are focused on the value of exhaust back pressure within the manifold. Thus, the benchmark for the design of the exhaust system is to keep the exhaust back pressure as low as possible. Since the flow within the exhaust system is a dynamic phenomenon even for constant engine speed (e.g., the gas discharge process varies according to the kinematic velocity of the pistons—Equation (1), and the exhaust valves opening), the authors paid attention to maintain the length of the four exhaust manifold ducts equal. Additionally, based on a previous study by R. Murali et al., which found that optimizing the exhaust manifold length can reduce the exhaust back pressure by 14%. The exhaust flow for the Formula Student car’s optimal solution was investigated using the Finite Element simulation to determine the magnitude of the gas velocity and the pressure distribution at three engine speeds (5000, 10,000, and 15,000 rpm). As is known, high back pressure in the exhaust system has undesirable effects on power output and, generally, on fuel consumption of an engine. But, regarding the cases of racing cars which are operated at very high engine speed, the effect of increasing of exhaust back pressure is possible to lead to desired effects as for the increasing of volumetric efficiency of the engine at very high rotation speed since the inertia of the intake air alongside with the ‘flow restriction’ from the exhaust will extent the time in which the combustible mixture remains in the cylinders.

3. Simulation of the Exhaust System

Figure 1 shows the solution domain with the boundary conditions. More specifically, that figure shows the exhaust system and the 3D volume of exhaust gases, with the boundary and initial conditions within the exhaust (the solution domain simulated). In addition, the discretized solution domain, including cut-cell elements at the outlet of the manifold, the entrance of exhaust gases into the manifold, and the entire 3D volume simulated, is presented. The simulations were conducted in ANSYS Fluent using the k-ε model. ANSYS Fluent uses two-equation models to evaluate the behavior of turbulent bounded flows. It basically makes the turbulent velocity and the lengths to be evaluated independently available through two transport equations [

7]. The solution domain consists of 106,000 elements. The density of the mesh is noticeable.

For all engine speeds, the time step remains constant at 0.025 ms. The only two parameters that have been changed are the solution time and the gas velocity at the entrance to the exhaust manifold. The velocity of the gases entering the exhaust manifold was calculated using kinematic principles based on the velocity of pistons within the cylinders, which discharge the gases during the exhaust stroke. The calculation of the piston’s velocity is expressed by a specific equation [

8]. To assess the effect of the design domain, the worst-case scenario was considered. This scenario presupposes that the velocity of the exhaust gases entering the manifold equals the velocity of the pistons during the exhaust stroke. Therefore, losses due to gas passage through the cylinder head were neglected. This extreme scenario was chosen to assess the behavior of the entire exhaust manifold under the most demanding conditions. Information about the typical composition of the gases resulting from the combustion process in Spark Ignition engines was taken from other studies [

9]. Thus, a user-defined gas was formed in ANSYS Fluent.

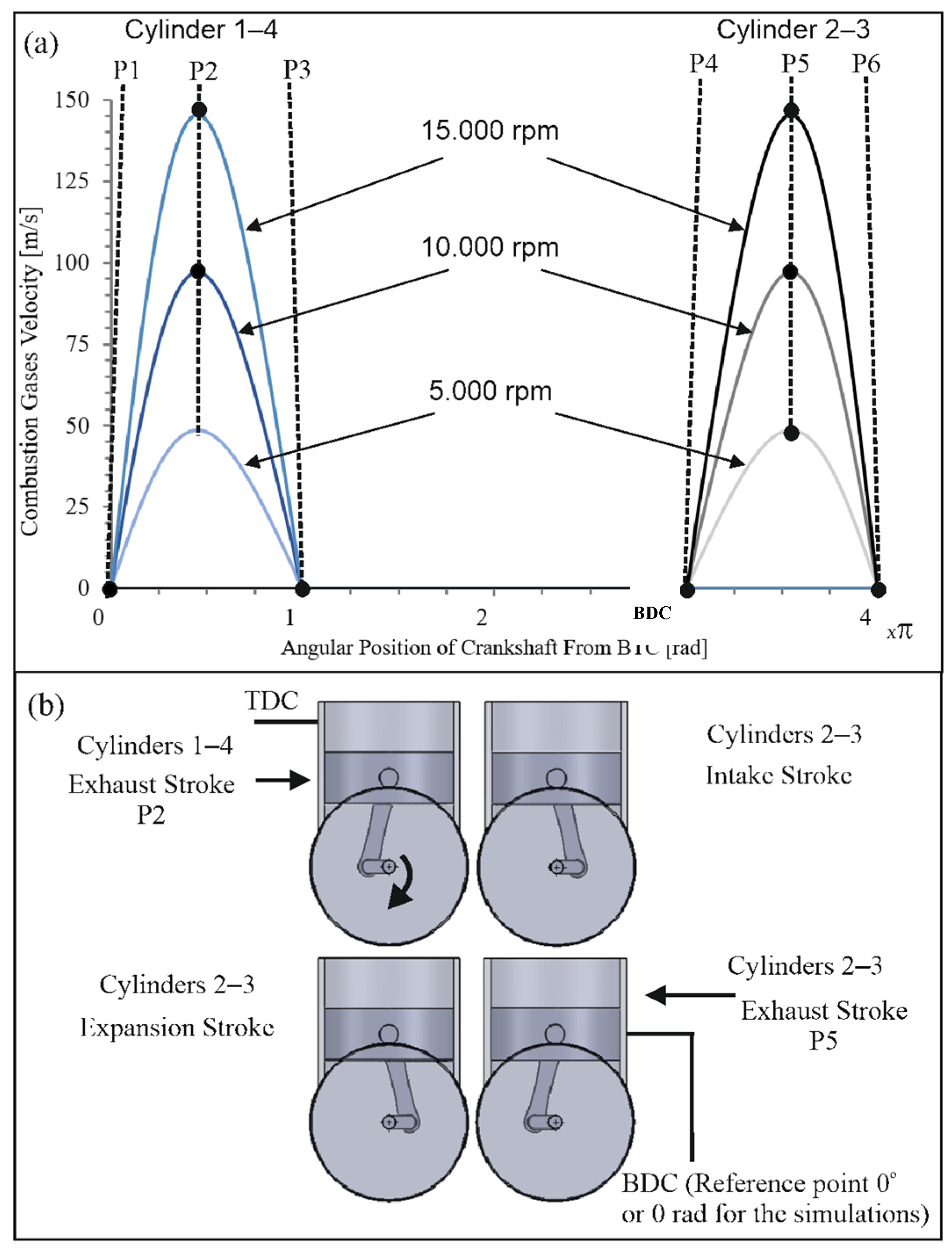

Figure 2 shows the piston velocity as a function of the crank angular position in radians during the exhaust process for the four cylinders of the engine. In these diagrams, the angular position of the crankshaft during the exhaust stroke for the four cylinders is illustrated. The points P1, P2, P3, P4, P5, and P6 correspond to the angular positions of the crankshaft during the exhaust stroke for the pairs of cylinders 1 and 4, and 2 and 3. In the figure, the angular position during the exhaust stroke for piston P2, where, according to Equation (1), the velocity of the piston is maximum. The simulation started at the moment when pistons 1 and 4 were at BDC. As previously explained, the worst-case scenario (maximum gas velocity for each engine speed case) was considered (e.g., the gas velocity at the exhaust manifold inlet equals the piston velocity during the exhaust stroke, and pressure loss in the cylinder head was not considered). Additionally, to simplify the problem and focus on the transient state of the exhaust stroke by observing maximum velocities, no overlapping period was considered.

Equation (1), shown below, was employed to calculate the piston’s velocity during the expansion stroke. It is basically the instantaneous velocity of pistons as a function of the angular position of the crankshaft.

where

is the crank radius that was taken equal to 0.0141 m for the 600 cc engine, λ is the ratio of r over the connecting rod length, and it was taken as 0.154, ω is the angular speed of the engine, and θ is the angular position of the crankshaft in radians. For the calculations of the instantaneous piston velociDty, a step of 0.1745 radians was considered. The gas velocities for the four cylinders were entered into ANSYS Fluent via a short UDF that employs linear interpolation to insert the instantaneous gas velocity at the current simulation time step.

All simulations were initiated in ANSYS Fluent with constant pressure throughout the exhaust system. It was difficult to evaluate the exhaust system pressure before the simulations. This is because the simulations were performed prior to the construction of the exhaust system, as the purpose was first to understand the behavior of the gases and then to optimize their performance. This approach, along with the trial-and-error procedure referred to above, assisted the overall design optimization. The exhaust gas flow will do the rest regarding the pressure variation throughout the entire simulation. Furthermore, at the very high engine speeds at which motorcycles’ engines rotate, there is little scientific evidence on the exact amount of back pressure. In addition to the above, authors cannot be based on particular studies since exhaust system design varies from case to case. The initial pressure used in the simulations was a typical back pressure of 25 kPa for the case of gasoline [

10].

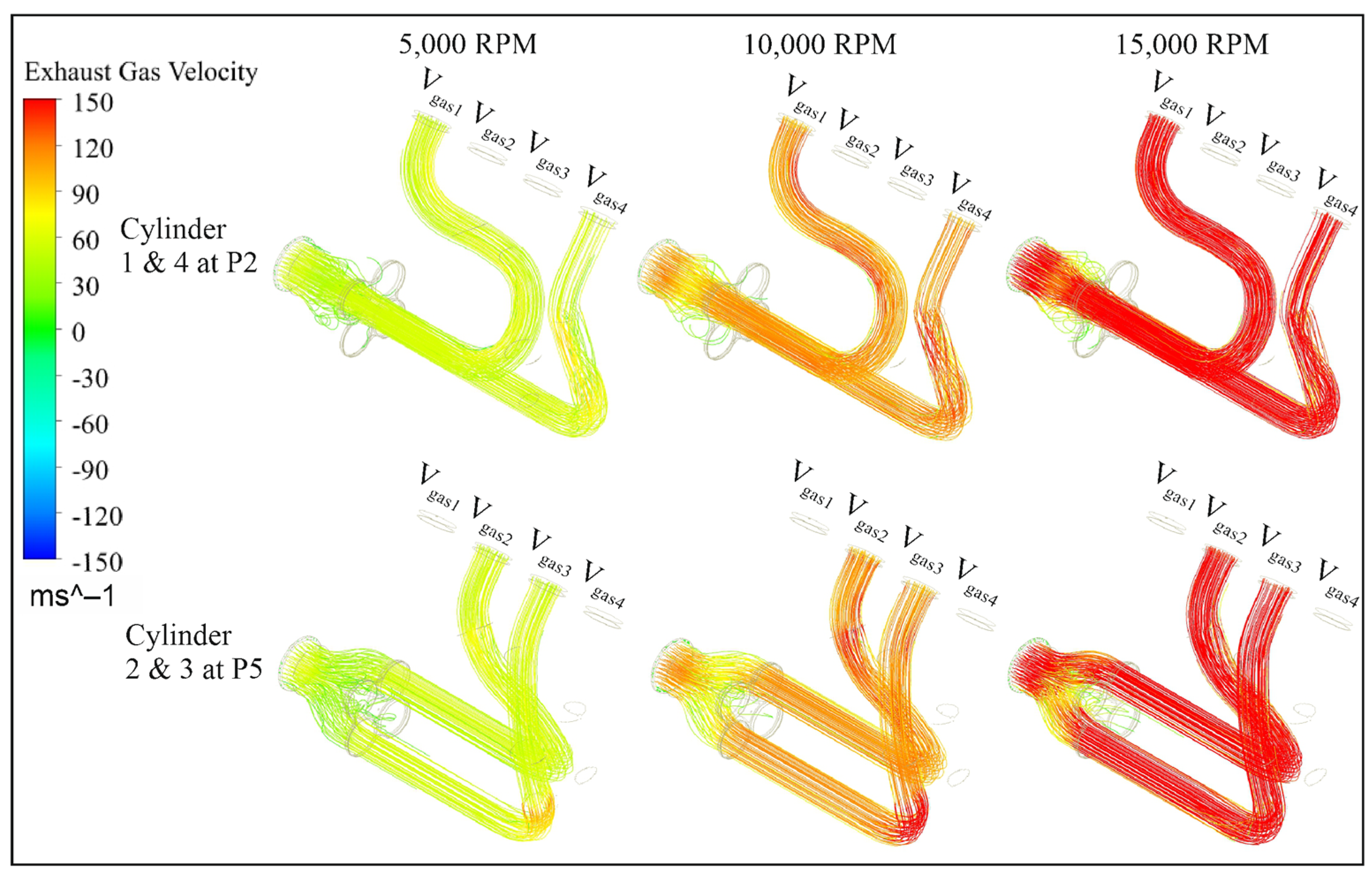

The magnitude of the exhaust gas velocity at engine angular speeds of 5000, 10,000, and 15,000 rpm is calculated using a known equation that considers the u, v, and w velocity components. The notations P2 and P5 represent points of angular crankshaft position in radians during the exhaust stroke of all cylinders. According to the simulation results, some velocity magnitudes drop in the joint region of the exhaust ducts just before the outlet. This was more noticeable at 5,000 and 10,000 rpm. The positive parameter that makes the current design successful is that the sharp increase in pressure at this point was avoided. Thus, the negative effect of back pressure will also be reduced. At this point, some vertices are generated due to gas-induced reduction in cross-sectional area. This phenomenon can be observed in

Figure 3, where the streamlines are presented. A venturi effect is also present in the nearest exhaust manifold outlet region. This is the object of a future study, in which its effect on back pressure will be investigated in parallel with the latter’s effect on volumetric efficiency at very high engine speed. It has to be stated that normally aspirated engines usually suffer a decrease in volumetric efficiency at high engine speeds.

The pressure distribution on the exhaust gases volume was also analyzed. The increase in the exhaust gas velocity causes an increase in pressure in the exhaust ducts in the area of the cylinders. The interesting notation is that the pressure decreases up to the last elbows and remains constant until the venturi effect is observed. This interesting phenomenon is mainly observed at engine speeds of 5000 and 10,000 rpm. The pressure remains as high as it enters the exhaust manifold throughout the entire route of gases towards the point of the venturi effect. One may expect that the pressure slightly increases at the point where the vortices appear, since the gas encounters a narrower cross-sectional area and the velocity in the axial direction decreases. The volume of the exhaust system sections allows the gas to rotate in a manner that prevents choked flow in all directions (before the venturi effect).

According to R. Murali et al., back pressure is the pressure produced by the engine to overcome the hydraulic resistance of the entire exhaust system and discharge the gases into the environment [

1]. In their study, they considered back pressure to be the gauge pressure measured at the outlet of an exhaust turbine. For the sake of similarity, in the present study, the authors considered the pressure at the exhaust manifold outlet as back pressure. In the simulations below, the pressure is defined as gauge pressure. One may observe that back pressure increases with increasing piston speed in all three examined cases. The positive finding is that, despite the engine having a high compression ratio and being capable of rotating at very high speeds (5000 and 10,000 rpm), the back pressure does not exceed 10 kPa. At 15 k rpm, the back pressure is between 34 and 56 kPa, which is considered very satisfactory given the engine’s technical specifications.

Figure 3 indicates the velocity streamlines for 5000, 10,000, and 15,000 rpm when the piston’s velocity becomes its highest values (P2 and P5 crankshaft angular positions). The first row shows the results for the exhaust stroke in cylinders 1–4, and the last row shows the exhaust stroke of cylinders 2–3. The streamlines in all cases show a decrease in velocity magnitude before the outlet, and some vertices appear at those points. The phenomenon seems to be more intense at 15,000 rpm.

5. Conclusions

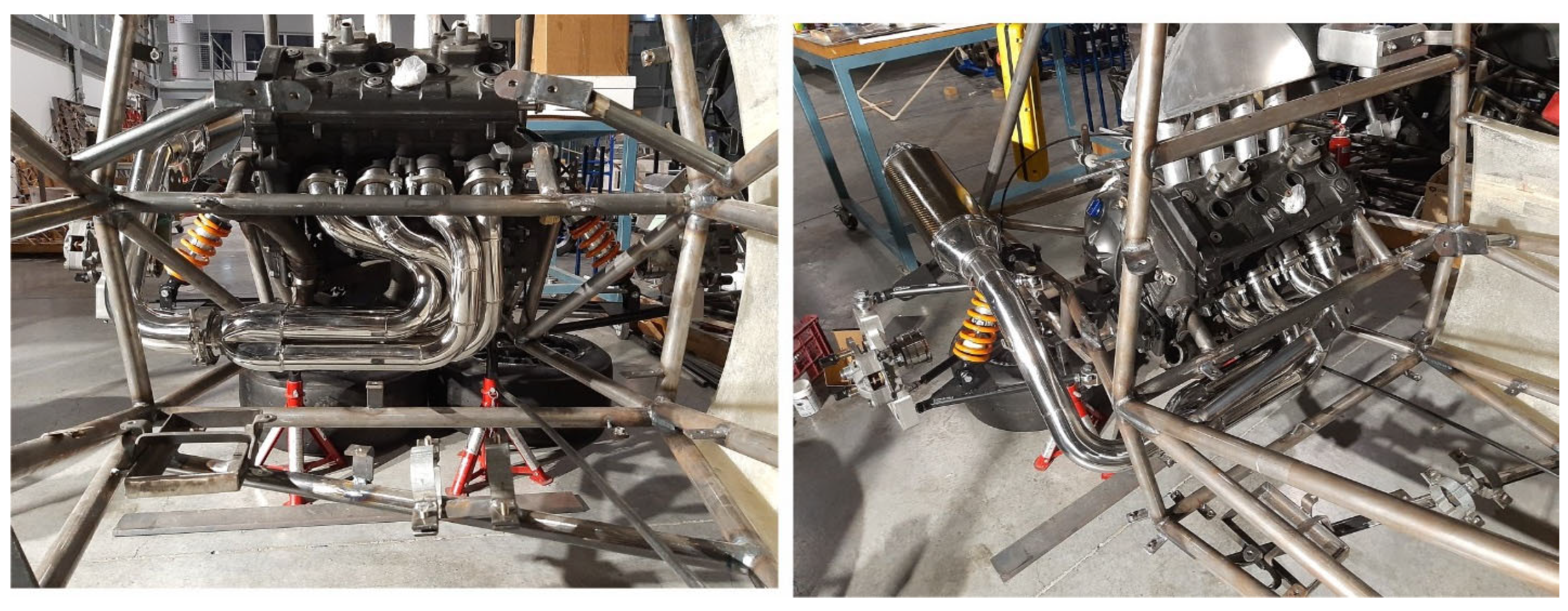

Designs, simulations, and trial-and-error procedures led to the optimization of the Formula Student racing car exhaust manifold. To assess the functionality and efficiency of the presented exhaust manifold, simulations were conducted at 5000, 10,000, and 15,000 rpm. For the simulations, the k-ε model was implemented. The parameter that assesses the success of the exhaust system design is the back pressure. The increase in back pressure affects the filling of the cylinders with fresh mixture, since both the intake and exhaust valves are open simultaneously for a short period. Thus, based on the results listed in the literature, the back pressure was reduced compared to other studies. The referred study results were presented up to 15,000 rpm. In the present study, for all engine speed cases, the pressure is the back pressure. The automatic optimization of the exhaust design is going to be conducted using Neural Networks or Adjoint Solver.