1. Introduction

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted by the United Nations on 25 September 2015 in New York, includes 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Among them, SDG 11 aims to “make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable” [

1,

2]. This goal emphasizes the importance of accessible transportation and inclusive public spaces, particularly for vulnerable groups such as women, children, older adults, and persons with disabilities.

In the context of urban planning and design, accessibility—defined by the Building Act No. 283/2021 Coll., Section 13(d) [

3], as the creation of conditions for the independent and safe use of land and buildings by persons with mobility, visual, or hearing impairments, older adults, pregnant women, and individuals accompanying a child in a stroller or a child under three years of age—is not merely a technical requirement, but a fundamental human right.

Public spaces, as defined in Act No. 128/2000 Coll., Section 34 [

4], include all squares, streets, marketplaces, sidewalks, public green areas, parks, and other spaces accessible to everyone without restriction, regardless of ownership. These spaces must be designed to accommodate diverse needs and enable the independent and safe movement of all users. Although the Czech Republic has established legislative and regulatory frameworks to address these requirements, challenges persist in their consistent and effective implementation within the built environment.

The accessibility of public spaces is one of the fundamental principles and an integral part of the inclusive and sustainable development of our cities. Public space is not only a place for social interaction but also a symbol of equality and social cohesion. The accessibility of these spaces must therefore be ensured, particularly from the perspective of users with any kind of health impairment. The methodological basis of the contribution is an analysis of the need for an accessible environment in relation to disadvantaged user groups. The analysis includes current statistical data and, in connection with this, the necessary user perspective for ensuring independent movement and orientation in the urban environment, which monitors the relationship between the identification of problem areas and the requirements of an accessible environment.

2. Data and Methods

In accordance with Article 9 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, the Czech Republic is committed to enabling persons with disabilities to live independently and participate fully in all aspects of life [

5]. This commitment includes the removal of architectural and transport barriers, which is supported by legislative and regulatory frameworks.

Quantitative data were obtained from the Czech Statistical Office (ČSÚ) [

6], which conducts regular surveys focused on persons with disabilities. The last data collection took place in 2023–2024. According to these findings, approximately 15% of the population aged 15 and older, corresponding to 1.31 million people, reported having a long-term disability that limits their daily activities. More than half of this population was seniors aged 65 and older.

The most common forms of disability were physical/mobility impairments (affecting 952,000 people) and visual impairments (213,000 people), see

Table 1.

The survey reveals the main causes of disability, which, in the case of physical and visual impairment, are not primarily congenital defects. In the case of physical impairment, 82% of cases are caused by illness, 13% by injury, and only 6% by congenital defects. In the case of visual impairment, 83% of cases are caused by illness, only 2% by injury, and 14% by congenital defects.

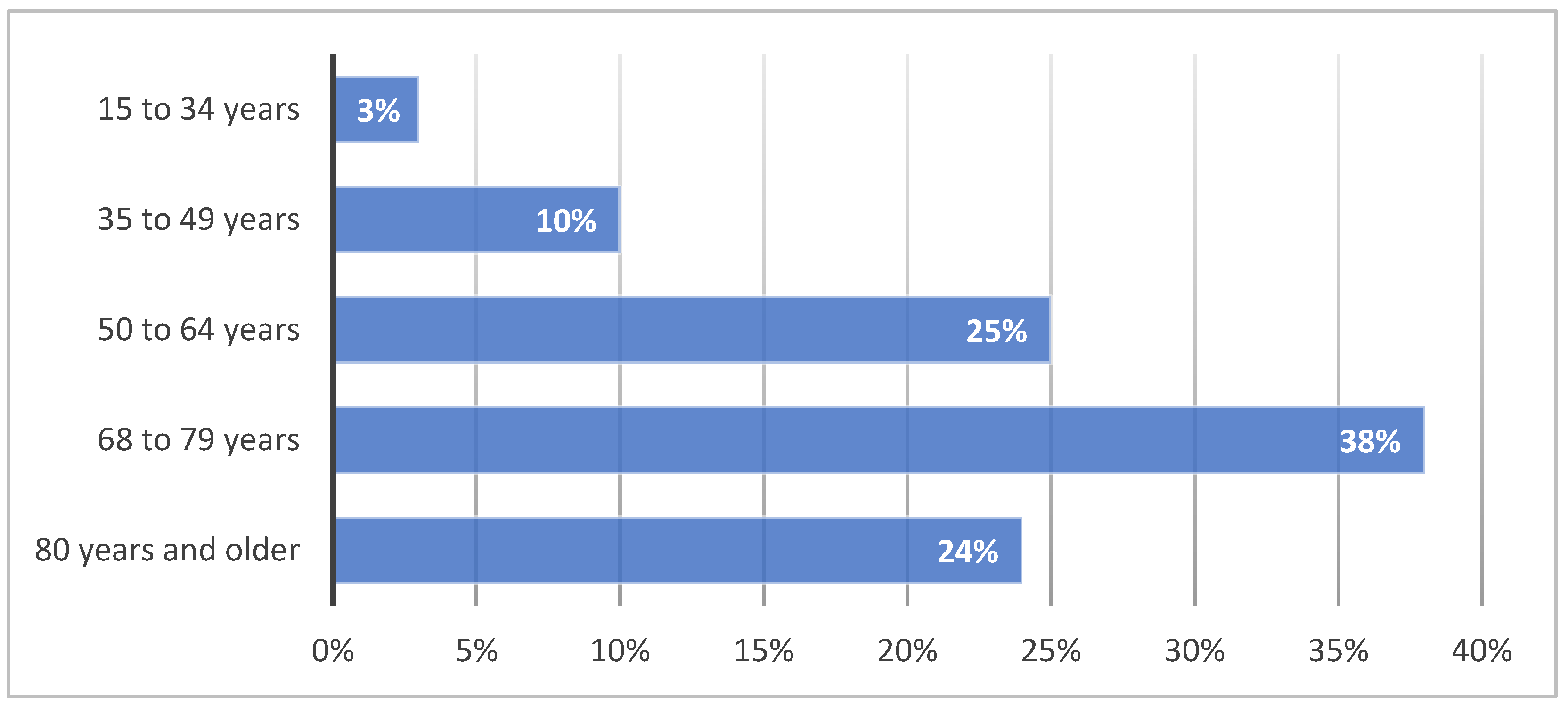

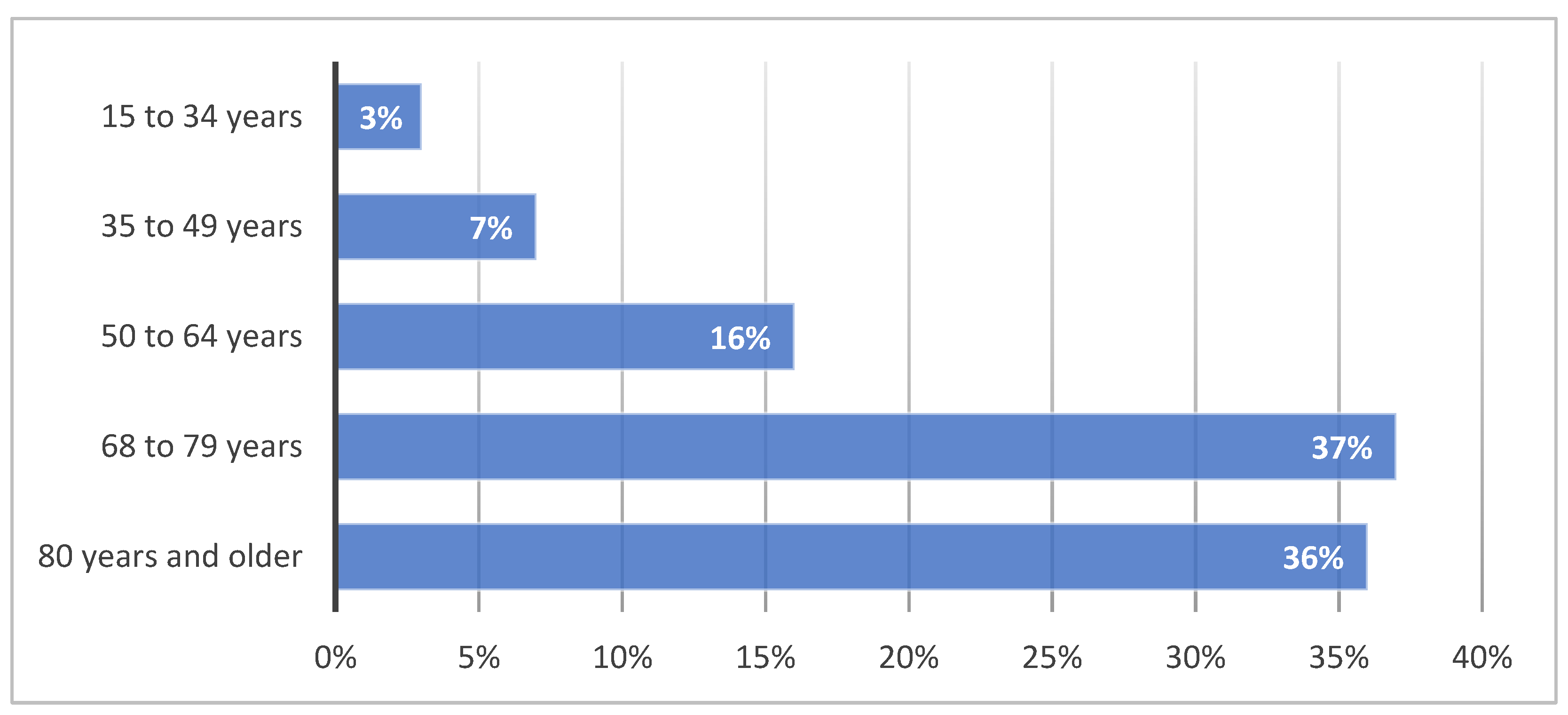

The analysis of the data also shows that the largest proportion of people with physical and visual impairments fall into the older age categories, i.e., disability increases significantly with age.

The largest proportion of people with mobility impairments encompasses the 68–79-year-old age group, accounting for 38% of the total, followed by the 50–64-year-old age group, accounting for 25% of the total, and the 80-and-over age group, accounting for 24% of the total. Almost 90% (87% to be precise) of people with mobility impairments are over 50 years of age, which indicates a strong correlation between age and the occurrence of mobility limitations, see

Figure 1.

Statistical data on visual impairment shows that almost three-quarters of people (73%) with visual impairment fall into the highest age categories. The largest share is represented in the 68–79-year-old age group, with a total of 37%, followed by the 80-and-over age group, with a total of 36%. These figures strongly indicate that population aging is the main factor contributing to visual impairment, see

Figure 2.

Difficulties associated with spatial mobility are most pronounced among seniors over 80 years of age. For example, 31% of this group have difficulty leaving their home or moving around independently. According to the CZSO, these difficulties affect both men and women.

Table 2 presents the difficulties in performing common activities by disability area (motor and visual) without reference to age or gender. Additionally, although regional differences are not explicitly detailed in the survey results, the prevalence of mobility problems is observed across demographic segments.

The survey results clearly show the number, structure, and basic problem areas of persons with disabilities in relation to the creation of accessible public spaces.

3. Results and Discussion

The basic philosophy of accessibility and barrier-free use in public spaces is to ensure the safe, free, and unrestricted movement of persons with disabilities, especially those with mobility and visual impairments.

Statistical data and

Table 1 also show that accessibility is related to the aging of the population. From this, it can be concluded that when addressing accessibility, it is necessary to take into account not only the issue of disability as such, but also to meet the requirements of individual age groups with the aim of creating a friendly environment that will promote quality of life and barrier-free access [

7] and optimize the movement of these users in the outdoor environment [

8]. A friendly environment will require an accessible and comfortable environment with the creation of safe urban public spaces without obstacles, suitable surfaces, and interesting architectural details [

9].

In the area of barrier-free modifications and accessibility of public spaces, roads, and transport terminals, the Czech Republic has succeeded since 2001 in creating a system that respects the specific user conditions of visually impaired people and people with reduced mobility through a legal and regulatory environment. Nevertheless, we still encounter a lack of understanding of the basic principles of independent movement and orientation, which leads to incorrect and very dangerous solutions, often endangering the health and lives of users.

When designing any building, we must address accessibility for persons with mobility and visual impairments separately, as they have completely different requirements for individual building modifications. A frequent source of errors in the design and implementation of buildings is failure to follow this methodological procedure and insufficient distinction between the requirements for accessibility and use of buildings for individual target groups with different health impairments [

10].

For mobility impairments, the main problem is physical barriers—significant height differences, large longitudinal or transverse slopes of walking surfaces, insufficient passage and maneuvering space, control elements located out of reach, etc. In the case of visual sensory impairments, the main problem is the lack and ambiguity of information about the building and its surroundings obtained non-visually, i.e., tactilely, mainly using a long white cane, and acoustically in changing situations.

3.1. Conditions for Easy Movement of Persons with Reduced Mobility

The group of persons with reduced mobility includes persons with severe and serious mobility impairments (persons in wheelchairs, persons using crutches or walking sticks), persons with temporary disabilities (temporary inability to move due to an accident), and last but not least, persons with mobility restrictions (senior citizens, pregnant women, persons with prams, etc.). To facilitate their movement, it is necessary to eliminate or ensure the possibility of overcoming differences in height levels, as height differences and gaps and joints in the walking surface, which can be easily overcome by other users, are insurmountable for these users. Overcoming any height difference or even the slightest slope in the walking surface requires considerable physical effort or presents an insurmountable obstacle for a person with limited mobility. A serious problem for this group of users in public spaces is the insufficient handling areas and passage widths of communication spaces. The layout and technical design must correspond to the maneuvering capabilities of compensatory aids and their collision-free passage, see

Table 3Figure 3 illustrates a misunderstanding of the basic accessibility principles in relation to a designated parking space for wheelchair users. In the example shown in

Figure 3, the surface of the parking space does not comply with the requirements for a level surface and maximum joint widths, and does not allow wheelchair users to maneuver easily when entering or exiting the vehicle.

3.2. Spatial Orientation and Independent Movement of Visually Impaired Persons

In order for visually impaired users to move freely and independently, they must be able to use spatial orientation and independent movement techniques [

11], and the design and construction of adequate architectural and structural modifications in public spaces must correspond to this, see

Table 4The basic method of obtaining unchanging information about a building and its layout for blind users is tactile, in particular through the use of a long white cane and footfall. For the correct design of public spaces that ensures the use of this technique for independent movement and orientation, the following basic conditions must always be met:

Ensuring free passage along the guide line and not placing any obstacles in the passage way along this guide line;

Compliance with the clearance height, which must not be obstructed by any elements of information systems, advertising signs, lighting, greenery, etc.;

Ensuring a sufficient number of natural and artificial tactile elements, including their dimensions, comprehensible continuity, and usable distances between them;

Ensuring tactile contrast with the surroundings for tactile elements located on surfaces, including their correct material design from certified products.

The photographs in

Figure 4 illustrate examples of misunderstanding the basic accessibility principles regarding independent mobility and spatial orientation for persons with visual impairments. Public spaces shall include guidance paths to assist persons with visual impairments in moving independently. No obstacles should be placed within the clear passage along the guidance path; if obstacles are present, they should be installed in such a way that the minimum passage width is maintained.

In the left-hand image, the natural guidance path (building facade) is not surrounded by a minimum clear passage of 900 mm when a single obstacle (street lamp) is installed. As a result, a blind person encounters an obstacle in their path that may be unseen and could cause an accident. Simultaneously, users in wheelchairs or with strollers are prevented from using the sidewalk due to this obstacle.

In the middle image, the tactile element of the artificial guidance path (grooved paving) directs the blind person to the natural guidance path, but movement is further impeded by a barrier in the form of a large flower pot on the sidewalk. When following an artificial guidance path, movement occurs not only along the tactile element itself, but also adjacent to it, on the right or left side. For this reason, a minimum clear passage of 800 mm shall be maintained on both sides of the axis of the tactile element.

The image on the right illustrates a critical error, where movement alongside the artificial guidance path at the side of the stairway significantly endangers a blind person. Their path leads into the space where the stair treads converge. This constitutes a serious hazard arising from a misunderstanding of the principles of movement and spatial orientation of blind persons.

When designing and implementing modifications for blind users, the correct use and creation of tactile elements must be respected, which always have a clear function and must be identifiable by a cane and by touch from the surrounding area [

12]. The function of tactile elements is always determined by two basic factors—the size of the tactile element and the nature of its surface, known as tactile contrast. [

13].

In

Figure 5, the correct and incorrect implementations of tactile contrast on an artificial guidance path are illustrated. The surface of a tactile element shall be flat, without protrusions, grooves, or similar shapes, and shall be non-slip for a minimum distance of 250 mm.

The figure on the left shows an example of a correct solution. A blind person using a long white cane and their feet must be able to detect and identify the tactile element, which provides basic information about the surrounding space.

The middle and right-hand images show solutions where the tactile element cannot be clearly perceived due to the textured surface of the adjacent paving and, at the same time, do not allow the blind person’s cane to slide smoothly.

The independent movement and orientation of visually impaired persons in public spaces is facilitated by color contrasts and changes in the structure of the walking surface. For easy identification of all-glass surfaces, stair treads, etc., visual contrast must be respected so that dangerous elements do not blend in with the background.

3.3. Principles of a Friendly and Accessible Urban Environment

The basic principle of creating safe, inclusive, and accessible public spaces is accessible pedestrian routes [

14] that respect the principles of independent movement and orientation of persons with disabilities. The following minimum requirements and recommendations are based on the following principles:

Accessible routes should be usable by all users regardless of age or disability.

There must be at least one accessible route in the area connecting all public facilities of interest with accessible entrances and adjacent parking spaces, accessible street furniture, and public transport stops.

Accessible routes must be equipped with accessible orientation and directional information in the form of tactile elements and visual contrasts to facilitate orientation and directional guidance for all users, not only those with visual impairments.

Accessible routes must have height differences resolved without compensating steps, respecting the maximum slope parameters, and if there are height differences on the route, an alternative directly proportional route must be available.

The surface of accessible routes must be level to prevent tripping, solid for easy movement of prams and wheelchairs, and have adequate anti-slip properties.

Accessible routes must have sufficient passage width corresponding to their purpose and intensity of use, without any protruding parts into the passage profile. Street furniture or technical equipment in the area must not restrict free movement, and their location must not reduce the passage width of accessible routes.

Accessible routes and their width must allow different users to pass each other, e.g., wheelchair users or wheelchair users with a stroller.

The sufficient width of the accessible route must allow for maneuvering with compensatory aids and, in particular, for handling wheelchairs.

The accessible route must facilitate the independent movement of visually impaired persons by providing guide lines and directional guidance.

A minimum clearance height must be maintained along the entire length of the route, including the height of tree crowns.

The accessible route must be properly drained; if drainage grates or gutters are used, their openings must not prevent independent movement, e.g., by trapping the tip of a white cane or the wheels of a wheelchair or pram.

An important safety feature of an accessible route is accounting for visual contrasts and ensuring uniform lighting along the entire length and width of the route.

It is advisable to supplement the accessible route at regular intervals with rest areas with appropriate furniture, in particular ergonomic seating elements suitable for the needs of older users and persons with disabilities.

It follows from the above that the recommendations concerning the most vulnerable users, namely persons with mobility and visual impairments, apply to accessible cities for all. These recommendations are based on the logic and principles of independent movement and orientation of persons with disabilities while ensuring the safety of all users. At the same time, these recommendations constitute the basis of the new normative framework [

12], which specifies and supplements accessibility requirements and concrete measures established under the Czech Building Act [

3] and, in line with the principles of the European standard [

14], the functional requirements for the accessibility and usability of the built environment.

4. Conclusions

The issue of accessibility and barrier-free use, in relation to the application of the principles of a city for all, should be a standard and an integral part of public spaces as a key element of modern society. Although specific legal provisions have been established to ensure accessibility, new developments still present barriers that hinder the free use, independent movement, and spatial orientation of persons with disabilities. These negative phenomena, which often pose a risk to the health and safety of the target users, are caused by a lack of knowledge of movement logic, spatial requirements and handling, and principles of spatial orientation, particularly in relation to persons with visual impairments.

A welcoming and accessible city for all, providing a barrier-free environment, must largely rely on methods of training and education in spatial orientation and independent mobility for persons with visual impairments. A thorough understanding of the capabilities and needs of persons with disabilities, including seniors, contributes to the creation of a safe, user-friendly, and accessible urban environment. Accessibility should be perceived not only as a legal obligation but also as a moral and societal responsibility.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.Z. and J.T.B.; methodology, R.Z.; software, J.T.B.; validation, R.Z. and J.T.B.; formal analysis, J.T.B.; investigation, R.Z. and J.T.B.; resources, R.Z. and J.T.B.; data curation, R.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, R.Z.; writing—review and editing, J.T.B.; visualization, R.Z. and J.T.B.; supervision, R.Z.; project administration, R.Z.; funding acquisition, R.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| UN | United Nations |

| CZSO | Czech Statistical Office |

| FCE | Faculty of Civil Engineering |

| VSB-TUO | VŠB-Technical University of Ostrava |

| ČSN | Czech Technical Standard |

| EN | European Norm |

References

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals; United Nations Information Center: Prague, Czech Republic. Available online: https://osn.cz/osn/hlavni-temata/cile-udrzitelneho-rozvoje-sdgs/ (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Sustainable Development, United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Act No. 283/2021 Coll., Building Act, as Amended; Ministry of Regional Development of the Czech Republic: Prague, Czech Republic, 2021.

- Act No. 128/2000 Coll., on Municipalities (Municipal Establishment), as Amended; Ministry of Regional Development of the Czech Republic: Prague, Czech Republic, 2021.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Communication No. 10/2010 m.s. Coll. on the Conclusion of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; Ministry of Foreign Affairs: Prague, Czech Republic, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Czech Statistical Office. Persons with Disabilities in Households; CSO: Prague, Czech Republic, 2025; ISBN 978-80-250-3584-9. [Google Scholar]

- Famakin, I.; Leung, M.Y. A Comparison of Barrier-Free Access Designs for the Elderly Living in the Community and in Care and Attention Homes in Hong Kong. In Proceedings of the 21st International Symposium on Advancement of Construction Management and Real Estate; Chau, K., Chan, I., Lu, W., Webster, C., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Miura, T.; Yabu, K.I.; Ikematsu, S.; Kano, A.; Ueda, M.; Suzuki, J.; Sakajiri, M.; Ifukube, T. Barrier-Free Walk: A Social Sharing Platform of Barrier-Free Information. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 14–17 October 2012; pp. 2927–2932. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-80-260-2080-6. [Google Scholar]

- Zdařilová, R. Barrier-Free Use of Buildings—Basic Principles of Accessibility (TP 1.4); PROFESIS: Professional Information System of the Czech Chamber of Civil Engineers [Online]; ČKAIT: Prague, Czech Republic, 2007; Updated 2024; ISSN 1805-6032. Available online: https://profesis.ckait.cz/dokumenty-ckait/tp-1-4/ (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Růžičková, V.; Kroupová, K. A Look at Independent Movement and Spatial Orientation of People with Visual Impairments; Palacký University: Olomouc, Czech Republic, 2017; ISBN 978-80-244-5273-9. [Google Scholar]

- ČSN 73 4001:2024; Accessibility and Barrier-Free Use. Czech Standards Institute: Prague, Czech Republic, 2024.

- Zdařilová, R. Barrier-Free Use for Urban Engineers (TP 1.5); PROFESIS: ČKAIT Professional Information System [Online]; ČKAIT: Prague, Czech Republic, 2007; Updated 2024; ISSN 1805-6032. Available online: https://profesis.ckait.cz/dokumenty-ckait/tp-1-5/ (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- EN 17210:2021; Accessibility and Usability of the Built Environment—Functional Requirements. European Committee for Standardization/CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).