1. Introduction

Urban flooding, intensified by climate change and accelerated land-surface sealing, presents a significant challenge for contemporary urban environments. Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDSs) provide a decentralized and ecologically adaptive alternative to traditional piped drainage infrastructure by promoting surface water attenuation, infiltration, and treatment through natural processes [

1]. These systems are designed to mimic natural hydrological functions and enhance urban resilience. Empirical analyses indicate that a substantial proportion of Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS) exhibit declining performance within a few years post-implementation, a trend largely attributed to inconsistent maintenance protocols and the lack of real-time monitoring systems [

2].

Emerging digital technologies such as Building Information Modeling (BIM) and Facility Management (FM) systems hold substantial promise for improving the lifecycle performance of SuDS infrastructure. BIM provides structured visualization, data integration, and simulation capabilities, while FM platforms support routine operations and maintenance workflows. Yet, the integration of BIM and FM within the context of SuDS remains limited and underexplored in current practice [

3,

4,

5].

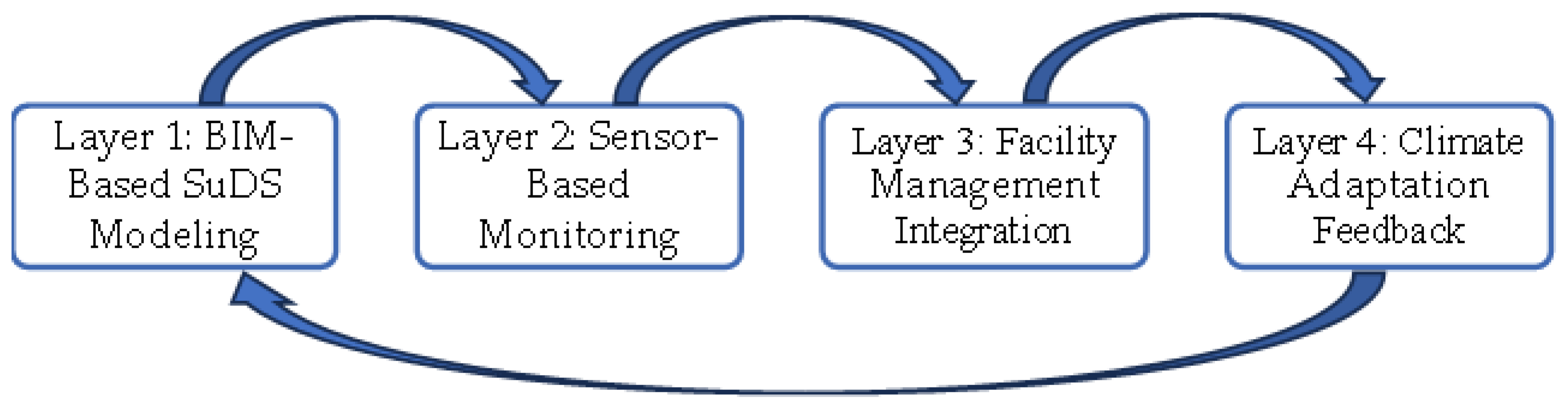

This study proposes a four-layer digital framework to bridge this gap and support the performance of SuDS assets.

2. Literature Review

2.1. SuDS Challenges in Urban Environments

Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDSs) components, such as bioswales, infiltration basins, and permeable pavements, provide ecologically effective solutions for managing urban runoff. However, their spatially distributed nature presents ongoing challenges for asset tracking and performance management. In the absence of a centralized digital asset register or real-time condition monitoring mechanisms, deterioration often remains undetected until system failures emerge [

2,

6]. Empirical findings from urban projects demonstrate a persistent dependence on manual inspection routines, which are both labor-intensive and subject to variability [

6]. Moreover, SuDS designs frequently fail to incorporate feedback from operational performance, limiting adaptive improvements and resulting in recurring inefficiencies and weak institutional loops [

3].

2.2. BIM and FM in Water Infrastructure

BIM tools generate comprehensive 3D parametric representations of infrastructure assets, facilitating hydrological modeling, construction sequencing, and strategic maintenance planning [

2]. Concurrently, FM systems are responsible for capturing and processing operational data, including work orders, inspection records, and condition assessments [

4]. Integrating BIM and FM platforms enables the creation of a digital twin as a synchronized virtual model that mirrors both the physical characteristics and real-time operational status of infrastructure components. In the context of urban stormwater management, such BIM and FM integration, particularly when coupled with sensor networks, has demonstrated measurable gains in efficiency, responsiveness, and system resilience.

3. The Four-Layer Digital Framework

The proposed BIM–FM–SuDS framework is organized into four integrated functional layers, each layer addresses a discrete system function: modeling, sensing, managing, and adapting. This is aligned with ISO 19650-compliant BIM workflows. A digital twin needs the following [

4]:

Physical Model;

Sensor Feedback;

Decision Engine;

Environmental Context.

The overall structure of the proposed four-layer integration approach is illustrated in

Figure 1.

3.1. Layer 1: BIM-Based SuDS Modeling

This foundational layer involves 3D modeling of SuDS components using Industry Foundation Classes (IFCs) classifications within compliant BIM tools. Features such as soil infiltration rate, vegetation type, and hydraulic properties are embedded in the model. Geographic Information System (GIS) integration enables large-scale mapping of urban catchments.

3.2. Layer 2: Sensor-Based Monitoring

Internet of Things (IoT)-enabled sensors collect real-time data on water levels, soil moisture, and flow rates. This data feeds directly into the BIM model, establishing a digital twin that supports failure prediction and condition-based maintenance.

3.3. Layer 3: Facility Management Integration

FM systems use sensor inputs to manage inspections, generate maintenance schedules, and trigger alerts. Beyond routine operational tasks, this layer establishes a continuous data feedback mechanism that updates and refines the BIM environment. As-built conditions, maintenance histories, vegetation health assessments, infiltration performance, and hydraulic behavior observations are systematically synchronized back into the BIM model. This bidirectional exchange transforms the BIM environment from a static design representation into a living operational database, ensuring that the digital twin evolves in parallel with real-world asset conditions. Such dynamic updating is essential for enabling predictive analytics, optimizing maintenance strategies, and supporting long-term lifecycle planning for SuDS infrastructure.

3.4. Layer 4: Climate Adaptation Feedback

The final layer integrates external datasets—such as updated rainfall projections and land-use maps—to inform adaptive design adjustments. This ensures that the SuDS system remains robust in the face of climate change and urban expansion.

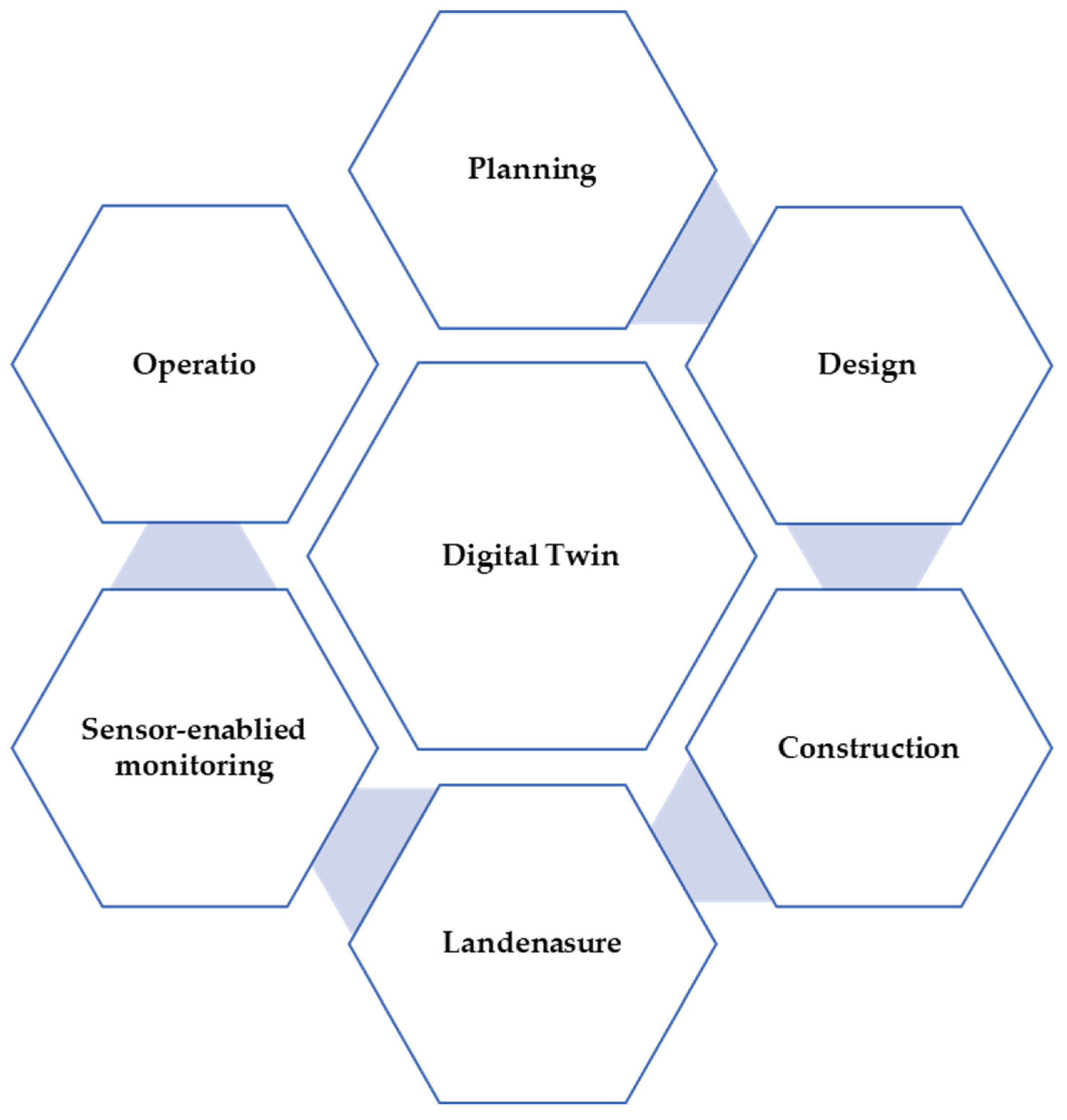

The lifecycle integration of SuDS within the digital twin environment is illustrated in

Figure 2.

Field observations from case studies across Europe and Asia demonstrated that adding more than four layers introduced redundancy without delivering additional value. Therefore, the four-layer structure offers a functionally complete yet streamlined solution.

The comparative assessment of traditional and BIM–FM–SuDS management approaches is summarized in

Table 1.

4. Discussion

The four-layer framework delivers several key benefits:

Lifecycle Optimization: Enables complete visibility from design through maintenance and adaptation.

Centralized Data Management: Merges design, operational, and environmental data into one system.

Predictive Maintenance: Real-time monitoring informs proactive interventions.

Resilience and Adaptability: Dynamic adaptation to changing climatic and urban conditions.

Despite these benefits, challenges such as high sensor installation costs, FM system complexity, and interoperability issues must be addressed. Solutions include prioritizing high-risk areas, training for FM tools, and adopting open standards like IFC.

Future work may explore integration with AI-based flood prediction, community-driven sensor inputs, and national digital infrastructure policies.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a robust digital framework that integrates BIM and FM technologies to enhance the design, monitoring, and adaptation of SuDS. Each of the four layers plays a vital role in transitioning SuDS from static systems to intelligent, adaptive infrastructure. Cities striving for resilience must adopt such digital paradigms to address the growing challenges posed by urbanization and climate variability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.L.P. and E.W.; methodology, T.L.P.; formal analysis, T.L.P.; writing—original draft preparation, T.L.P.; writing—review and editing, E.W.; visualization, T.L.P.; supervision, E.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cotterill, S.; Bracken, L.J. Assessing the Effectiveness of Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS): Interventions, Impacts and Challenges. Water 2020, 12, 13160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costin, A.; Adibfar, A.; Hu, H.; Chen, S.S. Building Information Modeling (BIM) for transportation infrastructure—Literature review, applications, challenges, and recommendations. Autom. Constr. 2018, 94, 257–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Succar, B. Building information modelling framework: A research and delivery foundation for industry stakeholders. Autom. Constr. 2009, 18, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieves, M.; Vickers, J. Digital twin: Mitigating unpredictable, undesirable emergent behavior in complex systems. In Transdisciplinary Perspectives on Complex Systems: New Findings and Approaches; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 85–113. [Google Scholar]

- Kamel, E.; Memari, A.M. Review of BIM’s application in energy simulation: Tools, issues, and solutions. Autom. Constr. 2019, 97, 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, R.; Digman, C.; Horton, B.; Gersonius, B.; Smith, B.; Shaffer, P.; Baylis, A. Using the multiple benefits of SuDS tool (BeST) to deliver long-term benefits. In Proceedings of the Novatech 2016—9ème Conférence Internationale sur les Techniques et Stratégies Pour la Gestion Durable de l’Eau dans la Ville/9th International Conference on Planning and Technologies for Sustainable Management of Water in the City, Lyon, France, 28 June–1 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).