1. Introduction

Mining activities have significantly shaped the natural and socio-economic landscape of Upper Nitra, especially in the Handlová -Nováky coal basin, where intensive lignite mining took place during the 20th and early 21st centuries. One of the most significant impacts of underground mining is the subsidence of the surface, which has led to the formation of depressions filled with surface and groundwater, which has gradually created wetlands and permanent or seasonal water areas. These anthropogenically created wetlands, in particular the Nováky–Koš complex, have become unique ecological systems with a higher biodiversity that often exceeds the surrounding agricultural areas [

1].

Monitoring and revitalisation of aquatic systems affected by mining activities in Upper Nitra represent a complex and interdisciplinary challenge. Wetlands created by subsidence bring both opportunities and risks: on the one hand, they contribute to ecological diversity and new recreational potential, but on the other hand, they reduce the usability of agricultural land and present long-term hydrogeological uncertainties. The disappearance of some wetlands due to drainage, natural siltation or reclamation efforts to return land to agriculture highlights the dynamic nature of these ecosystems and the need for their constant monitoring [

2].

Recent research in the Basin has focused on the development of four major wetlands (Wetland Nos. 1–4), assessing their hydrological balance, ecological functions, and long-term sustainability. For example, Wetland 3 is currently the only one that is permanently supplied with water from both mine drainage and geothermal inflows, highlighting the importance of water resource management for wetland persistence. Other wetlands are more vulnerable to desiccation, succession and land use change, underscoring the need for adaptive revegetation measures [

3].

From an economic point of view, these wetlands make it impossible to use part of the agricultural land, leading to income losses and raising questions about compensation or alternative land uses. At the same time, there are proposals to transform former tailings ponds, such as the New Cígeľ tailings pond, into recreational water reservoirs, which would create potential for regional development and ecotourism. However, such transformations require accurate hydrogeological assessment and long-term monitoring to avoid secondary contamination or instability [

3].

The environmental and political framework for these activities is shaped not only by Slovak legislation but also by international obligations, including the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance, the EU Water Framework Directive, and the Paris Climate Agreement. National programmes, such as the Slovak Wetland Care Programme, emphasise the prevention of wetland loss and the integration of wetland revitalisation into spatial planning [

3].

For this reason, it is essential to implement comprehensive monitoring strategies. These combine geological, hydrological and ecological data with socio-economic analyses in order to assess both the risks and benefits of post-mining wetlands. As recent case studies show, effective monitoring not only allows for early detection of negative impacts (e.g., water pollution, uncontrolled drainage) but also provides the basis for revitalisation policies aligned with sustainable development goals [

4,

5].

The revitalisation of water systems in Upper Nitra represents a microcosm of the wider European post-banking challenges. The transformation of this coal region towards a post-extraction future must address ecological restoration, economic restructuring and social adaptation in parallel. Monitoring plays a key role in this—ensuring that newly created ecosystems, such as wetlands, are not lost, but integrated into the cultural landscape of Upper Nitra as valuable natural and social resources [

6].

The article will specifically address the issue of monitoring and revitalisation of water systems affected by mining activities in Upper Nitra, focusing on the investigation of wetlands and water depressions created as a result of undermining and brown coal mining closure. Their hydrological and ecological functions, their impact on agricultural land and the possibilities of their integration into the landscape through reclamation and revitalisation measures will be analysed. The main problems of the region include, in particular, the risk of drying up wetlands, the loss of agricultural production, hydrogeological instability and the need to transform tailings into a purpose-built use for local communities. We have divided the paper into the following sections: Introduction, Methodology, Analysis of Results, and Conclusion.

We set out two initial theses for the article:

Thesis 1: Revitalisation and long-term monitoring of wetlands created by mining activities in the Upper Nitra can contribute to increasing the ecological stability and biodiversity of the region.

Thesis 2: Properly designed revitalisation measures and the use of tailings for recreational or environmental purposes can mitigate the negative socio-economic impacts of the cessation of mining activities in the region.

2. Methodology

The issue of monitoring post-mining revitalisation described in our paper is based on an interdisciplinary approach that links elements of environmental geography, hydrogeology, ecology and socio-economic analyses. The aim is to provide a comprehensive view of the process of monitoring and revitalisation of aquatic systems affected by mining activities in the Upper Nitra region, with an emphasis on wetlands and depressional basin systems created as a result of undermining. Below, we present the methodology and procedure for processing the analyses and results of the work.

Analysis of existing data and documents:

- -

Use of primary data from the report of Hornonitrianske bane Prievidza, a. s., which documents the development of depressional basins, monitoring of mine waters and the condition of tailings (Old and New Cígeľ tailings).

- -

Secondary data—scientific studies, as well as governmental and European documents (e.g., Ramsar Convention, Water Framework Directive, and National Wetland Care Programme) [

7,

8,

9].

- -

Geological and hydrogeological maps and archival mining documents to identify changes in relief and the dynamics of aquifer systems.

Field monitoring and direct observation:

- -

Passporting of wetlands 1–4—description of their historical development, changes in area over time (based on satellite imagery, mining maps and orthophotos), and current ecological status.

- -

Water quality monitoring—evaluation of physico-chemical parameters (pH, conductivity, as well as metal and sulphate content of mine waters) that have been identified in previous research as critical factors (e.g., Acid Mine Drainage—AMD).

- -

Hydrological measurements—monitoring the water balance of wetlands, their recharge sources (rainfall, groundwater, and mine water) and identifying seasonal changes.

Economic and social analysis:

- -

Quantification of agricultural land losses and economic impacts associated with the creation and expansion of wetlands.

- -

Assessment of recreational and ecological potential—exploring the potential for conversion of selected tailings ponds into recreational zones and their economic benefit to the region.

- -

Social dimension—to determine the attitude of the population towards the revitalisation and new use of the areas (based on available regional evidence and previous studies).

Comparative analysis and synthesis of results:

- -

Comparison of revitalisation processes in Upper Nitra with model examples from Europe (e.g., Wallasea Island in the UK).

- -

Identification of similarities and differences in conditions in order to develop adaptable recommendations for Slovakia.

Future research.

3. Analysis of Results

Most of the work and research has focused on the assessment of fauna and flora associated with wetland habitats. Information on the flooded sites themselves and their causes has not yet been published. There have been no scientific studies assessing the condition of the sites in question and the trend of their future development. The wetlands between Nováky and Kos have not only been created, but many of them have already disappeared. This is due to reclamation activities aimed at returning waterlogged agricultural land to its original use, as well as to natural development, when these sites change their character and gradually dry up as a result of afforestation.

3.1. Monitoring the Revitalisation of Aquifer Systems

Monitoring of aquatic systems in the Upper Nitra area has shown a significant dynamic in the development of wetlands that have been created as a result of surface subsidence following many years of lignite mining. Particularly important is the monitoring of wetlands 1–4 in the Nováky I mining area. These wetlands represent unique ecosystems whose existence is conditioned by a combination of natural and anthropogenic factors. The monitoring results show that while some wetlands are capable of long-term stability (e.g., Wetland No. 3 fed by mining and geothermal waters), others are significantly threatened by desiccation and loss of ecological functions.

Wetlands in the Nováky I mining area (MA) have started to form in the wider surroundings of the village of Kos and the urban area of Laskar above the mined-out parts.

These flooded and waterlogged depressions in the landscape structure increase the areal representation of aquatic and wetland habitats. At the same time, the area of agrocenoses decreases, but the reduction in the area of intensively farmed areas is not environmentally critical. The number and location of wetlands within the DP are changing over time. As mining activity continues, new waterlogged depressions are created, or the extent of existing wetlands is altered, particularly in the area of KP 11 (see

Figure 1). Depending on climatic conditions, the amount of atmospheric precipitation and other external factors, such as reclamation activities, some smaller waterlogged depressions have disappeared (dried up or been filled in).

A detailed analysis of the extent of wetlands over the last decades has shown their gradual changes: some have shrunk as a result of drainage or sedimentation, while others have expanded following the cessation of extractive activities. The ecological importance of these wetlands is unquestionable—they form habitats for a variety of bird, amphibian and plant species that would not otherwise find suitable conditions for survival in an intensively used agricultural landscape.

3.2. Wetland 1 and Wetland 3

The Wetland 1 currently has the character of a lake with a permanent water surface. The greatest bottom depth below the water surface has been detected by sonar and is 11.5 m deep (see

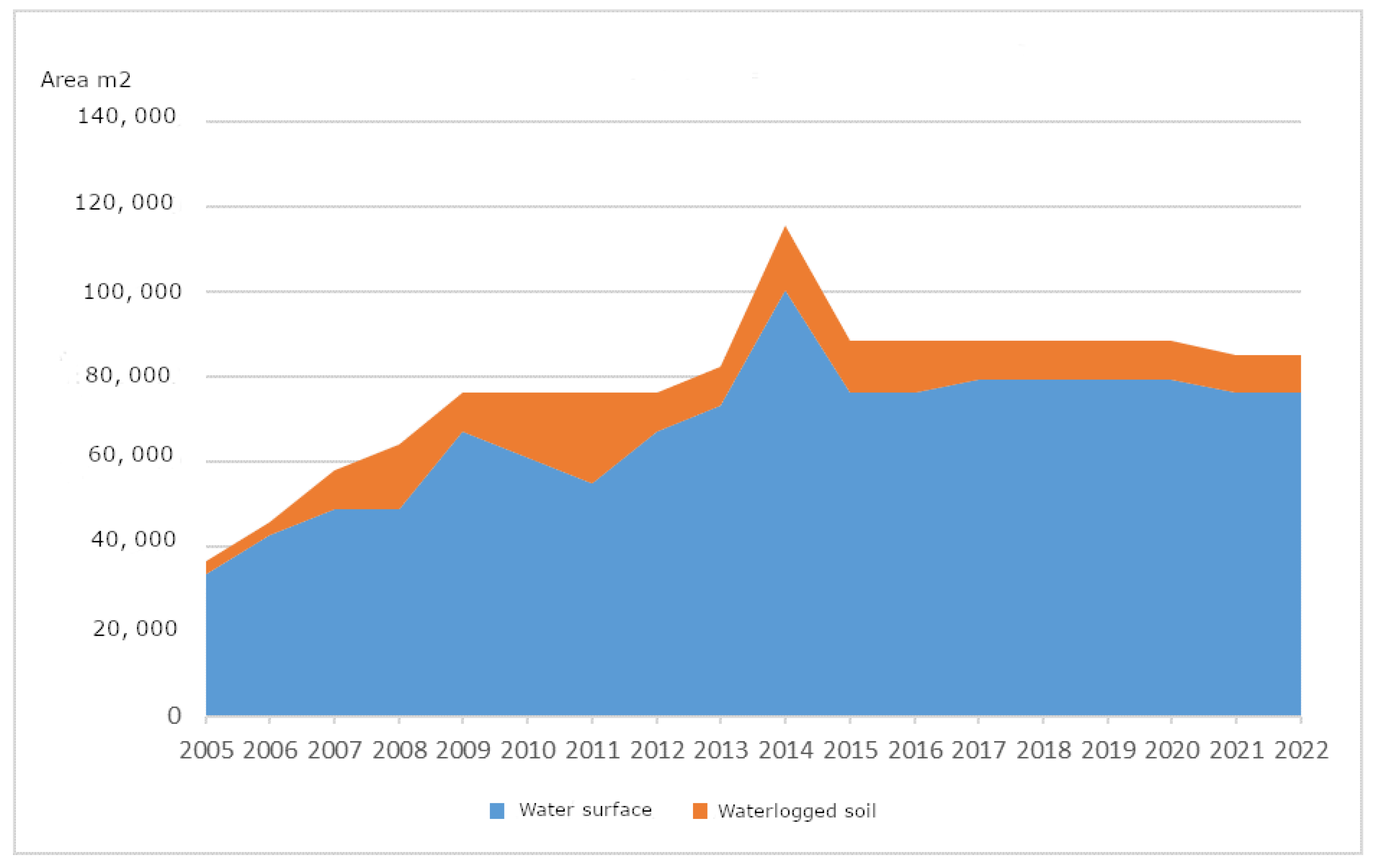

Figure 2). The status of the water body is stable and has not changed in the long term, and the temporal evolution of the water surface area and the waterlogged area of Wetland 1 is shown in

Figure 3.

Wetland No. 3 has the character of a large lake. At present, it is the water body with the largest area in DP Nováky I. Its common name is the Laskarska wetland or also the Ťakovsko–Metrboska wetland. The water body has an irregular shape, which was formed by the connection of several waterlogged subsidence basins, which were formed by the gradual stripping of coal reserves in the 11th HPP.

The formation of the flooded depression was caused by the deep mining of lignite coal that took place in the 11th KP of the Novak coal deposit between 2009 and 2020. Riparian vegetation: Due to the nature of the flooded land, the riparian vegetation is very heterogeneous. The part that is 2430 m long is bounded by arable land and is free of permanent vegetation, which represents 66.3% of the total wetland perimeter. The riparian vegetation on the original channels of the relocated watercourses Nitra, Ťakov, and Metrbos is on the 1233 m long section, representing 33.7%, dominated by tree cover and by sticky alder (Alnus glutinosa).

As a result of the ongoing quarrying, its area has steadily increased, gradually merging several formerly separate flooded depressions; see

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

A positive result of the monitoring is also an increase in the ecological stability of the area, which would be deprived of important ecosystem services without these anthropogenic wetlands. At the same time, however, their long-term sustainability is shown to depend on the proper management of water resources, including the regulation of mining and geothermal waters.

The risks identified include the following:

- -

Siltation and gradual drying up of some wetlands;

- -

Changes in water chemistry due to Acid Mine Drainage (AMD);

- -

Threats to biodiversity if water levels are reduced.

Thus, the monitoring results clearly show the need for long-term and systematic revitalisation, taking into account not only the ecological but also the socio-economic aspects of the region’s development.

3.3. Economic and Social Aspects of Revitalisation

The economic analysis of the revitalisation of water systems shows significant losses in agricultural production. Agricultural land flooded by water or waterlogged as a result of submergence is unusable for mechanisation, leading to a decline in yields and financial losses for local farmers. These losses can be quantified in thousands of euros per year for each affected area, which represents a significant problem for the regional economy.

The social aspects of revitalisation include, in particular, the attitudes of the population towards changes in the landscape. The results show that part of the population perceives wetlands negatively because of their limiting impact on agriculture, while others appreciate their ecological and recreational value. From the perspective of the region’s transformation, it is therefore important to seek compromise solutions that balance ecological, economic and social interests [

7,

10].

Key challenges include the following:

- -

Securing financial resources for revitalisation and monitoring;

- -

Developing compensation mechanisms for affected farmers;

- -

Integrating new recreational functions into regional planning;

- -

Mitigating the social impacts of mine decline through environmental projects.

4. Conclusions

Based on the analysis of the results, it is possible to formulate a number of recommendations that should serve as a basis for future research and practical steps in the revitalisation of water systems affected by mining activities in the Upper Nitra region.

Strengthening monitoring and systematic measurements:

- -

Introduction of a comprehensive monitoring system including hydrological, chemical, biological and socio-economic parameters.

- -

Extend monitoring to long-term monitoring of changes in water quality and biodiversity in order to capture gradual changes in ecosystems.

Revitalisation and adaptation measures:

- -

Stabilisation of wetlands through controlled inflow of mining and geothermal water to prevent their drying out.

- -

Implementation of ecological measures to promote biodiversity, such as planting suitable vegetation, creating nesting habitats for birds and promoting natural succession processes.

- -

Technical measures to prevent Acid Mine Drainage (AMD), including neutralising acidic waters and preventing contaminants from entering wetlands.

Economic and regional aspects:

- -

Develop strategies for compensating farmers whose land has been flooded or degraded due to subsidence.

- -

Promote projects that transform tailings into recreational and environmentally valuable spaces, creating new potential for tourism and ecotourism.

- -

Use of financial resources from European funds such as the Equitable Transformation Fund and the LIFE programme to co-finance revitalisation activities.

Social and community involvement:

- -

Conduct education and information campaigns for the local population to improve the perception of the importance of wetlands and landscape revitalisation.

- -

Involvement of local communities in decision-making processes in the planning of revitalisation measures, thereby strengthening their acceptance and sustainability of the projects.

Future research:

- -

Detailed modelling of the hydrological balance of wetlands and simulations of possible climate change scenarios.

- -

Research on the impact of revitalised wetlands on the air quality and microclimate of the region.

- -

Analysis of the long-term socio-economic benefits for the region if revitalisation measures are implemented.

The analysis of the results shows that the revitalisation of water systems in the Upper Nitra region is of a complex nature, which goes beyond environmental issues and extends to the economic and social spheres. Monitoring confirms the importance of wetlands as ecologically valuable ecosystems, but also reveals the risks associated with their long-term sustainability. Economic analyses point to the need to find alternative land uses and drainage areas that can compensate for the loss of agricultural production. Social factors highlight the importance of involving local communities and creating participatory solutions.

In terms of economic aspects, it is confirmed that the creation of wetlands leads to a reduction in agricultural production and to losses for the local population. On the other hand, the transformation of tailings ponds and depressional basins into recreational and environmentally valuable spaces offers new opportunities for the region’s economy. However, this process requires systematic planning, significant investment and, above all, the linking of environmental, economic and social interests.

The social dimension shows that successful revitalisation is only possible if local communities are actively involved. Acceptance by the population is crucial for the sustainability of the proposed measures and for creating a positive relationship with the transformed landscape.

The formulated theses are confirmed in the context of the results:

Revitalisation and long-term monitoring of wetlands can contribute to increasing the ecological stability and biodiversity of the region.

Properly designed revitalisation measures and the use of tailings for recreational or environmental purposes can mitigate the negative socio-economic impacts of mine closure.

The recommendations emphasise the need to link environmental, economic and social aspects into a coherent revitalisation framework. A key element in the successful transformation of Upper Nitra will be the development of a multidisciplinary approach that not only enables the restoration and protection of wetlands but also supports regional development and the quality of life of local residents. The end of coal mining creates space for the transformation of the region from a mining area into a space of ecological renewal and sustainable development. Monitoring and revitalisation of water systems will form the cornerstone of this transformation, which can also serve as an example for other European post-mining regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, A.S. and S.M.; methodology, A.S.; validation, N.K.; formal analysis, A.S.; investigation, N.K.; resources, N.K.; data curation, A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.; writing—review and editing, N.K. visualisation, N.K.; supervision, S.M.; project administration, A.S.; funding acquisition, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bajtoš, P. Bilancia hmotnostného prietoku kontaminantov v horských oblastiach zaťažených banskou činnosťou na príklade Sb ložiska Dúbrava a cu ložiska Slovinky. Podzemn. Voda 2012, 18, 110–122. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Aktualizácia Akčného plánu transformácie uhoľného regiónu Horná Nitra; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nováková, E.; Tóth, R. Socio-ekonomické aspekty útlmu baníctva a transformácie regiónov. Životné Prostr. 2020, 54, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bajtoš, P.; Zahorova, L.; Rapant, S.; Pramuka, S. Monitoring geologických faktorov vplyvu ťažby nerastov na životné prostredie v rizikových oblastiach Slovenska. Miner. Slovaca 2012, 44, 375–392. [Google Scholar]

- Majerník, M.; Tkač, M.; Bosak, M.; Andrejovsky, P. Management of Environmental Risk Tailing Ponds Dross Ashes Mixture. Životné Prostr. 2012, 46, 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Halmo, J.; Holý, M. Analýza vplyvu banskej činnosti na vznik mokradí v Nováckom ložisku. Acta Montan. Slovaca 2021, 26, 233–246. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstvo Životného Prostredia SR. Dohovor o Mokradiach Majúcich Medzinárodný Význam (Ramsarský Dohovor); MŽP SR: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Paris Agreement; United Nations Treaty Collection: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament & Council. Water Framework Directive 2000/60/EC; Official Journal of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerstvo Životného Prostredia SR. Program Starostlivosti o Mokrade Slovenska na Roky 2021–2030; MŽP SR: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).