Implementing the Physical Activity Vital Sign in a Pediatric Diabetes Center

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Comparing Clinical Factors Between “At-Goal” vs. “Not-at-Goal” PA Levels

3.3. Comparing Clinical Factors Between Three PA Levels

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 10. Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2025. Diabetes Care 2025, 48 (Suppl. S1), S207–S238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 14. Children and Adolescents: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care 2025, 48 (Suppl. S1), S283–S305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 5. Facilitating Positive Health Behaviors and Well-Being to Improve Health Outcomes: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2025. Diabetes Care 2025, 48 (Suppl. S1), S86–S127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michos, E.D.; Khan, S.S. Further Understanding of Ideal Cardiovascular Health Score Metrics and Cardiovascular Disease. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2021, 19, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; Allen, N.B.; Anderson, C.A.; Black, T.; Brewer, L.C.; Foraker, R.E.; Grandner, M.A.; Lavretsky, H.; Perak, A.M.; Sharma, G.; et al. Life’s Essential 8: Updating and Enhancing the American Heart Association’s Construct of Cardiovascular Health: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 146, e18–e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolfsson, P.; Taplin, C.E.; Zaharieva, D.P.; Pemberton, J.; Davis, E.A.; Riddell, M.C.; McGavock, J.; Moser, O.; Szadkowska, A.; Lopez, P.; et al. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2022: Exercise in Children and Adolescents with Diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2022, 23, 1341–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Absil, H.; Baudet, L.; Robert, A.; Lysy, P.A. Benefits of Physical Activity in Children and Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes: A Systematic Review. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 156, 107810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 7. Diabetes Technology: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2025. Diabetes Care 2025, 48 (Suppl. S1), S146–S166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergenstal, R.M.; Gal, R.L.; Beck, R.W. Racial Differences in the Relationship of Glucose Concentrations and Hemoglobin A1c Levels. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 168, 232–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liese, A.D.; Reboussin, B.A.; Kahkoska, A.R.; Frongillo, E.A.; Malik, F.S.; Imperatore, G.; Saydah, S.; Bellatorre, A.; Lawrence, J.M.; Dabelea, D.; et al. Inequalities in Glycemic Control in Youth with Type 1 Diabetes Over Time: Intersectionality Between Socioeconomic Position and Race and Ethnicity. Ann. Behav. Med. A Publ. Soc. Behav. Med. 2022, 56, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard Dicks, J.; McCann, L.J.; Tolley, A.; Barrell, A.; Johnson, L.; Kuhn, I.; Ford, J. Equity of Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Children and Young People With Type 1 Diabetes: A Systematic Review. Pediatr. Diabetes 2025, 2025, 8875203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smigoc Schweiger, D.; Battelino, T.; Groselj, U. Sex-Related Differences in Cardiovascular Disease Risk Profile in Children and Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.; Crapnell, T.; Lau, L.; Bennett, A.; Lotstein, D.; Ferris, M.; Kuo, A. Emerging Adulthood as a Critical Stage in the Life Course. In Handbook of Life Course Health Development; Halfon, N., Forrest, C.B., Lerner, R.M., Faustman, E.M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK543712/ (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Friedenreich, C.; Shiroma, E.J.; Lee, I.M. Physical Inactivity and Non-Communicable Disease Burden in Low-Income, Middle-Income and High-Income Countries. Br. J. Sports Med. 2022, 56, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golightly, Y.M.; Allen, K.D.; Ambrose, K.R.; Stiller, J.L.; Evenson, K.R.; Voisin, C.; Hootman, J.M.; Callahan, L.F. Physical Activity as a Vital Sign: A Systematic Review. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2017, 14, E123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd ed.; Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; 118p.

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, J.T.E. Eta Squared and Partial Eta Squared as Measures of Effect Size in Educational Research. Educ. Res. Rev. 2011, 6, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; William, C.B.; Barry, J.B. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.-Y. Statistical Notes for Clinical Researchers: Chi-Squared Test and Fisher’s Exact Test. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2017, 42, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henske, J.; Albashaireh, A.; Turner, L.V.; Beach, G.; Riddell, M.C. Are Regular Aerobic Exercisers With Type 1 Diabetes Following Current Physical Activity Self-Management Guidelines? Insights From an Online Survey. Clin. Diabetes: A Publ. Am. Diabetes Assoc. 2025, 43, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, M.; De Vito, G. Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Commonalities, Differences and the Importance of Exercise and Nutrition. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codella, R.; Terruzzi, I.; Luzi, L. Why Should People with Type 1 Diabetes Exercise Regularly? Acta Diabetol. 2017, 54, 615–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cock, D.; Schreurs, L.; Steenackers, N.; Pazmino, S.; Cools, W.; Eykerman, L.; Thiels, H.; Mathieu, C.; Van der Schueren, B. The Effect of Physical Activity on Glycaemic Control in People with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabet. Med. 2024, 41, e15415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, R.; Wittenberg, A.; Castle, J.R.; El Youssef, J.; Winters-Stone, K.; Gillingham, M.; Jacobs, P.G. Effect of Aerobic and Resistance Exercise on Glycemic Control in Adults With Type 1 Diabetes. Can. J. Diabetes 2019, 43, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Overall N = 304 | Young Adult N = 87 | Youth N = 217 |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Demographic | |||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 145 (48) | 44 (51) | 101 (47) |

| Male | 159 (52) | 43 (49) | 116 (53) |

| Race | |||

| Non-White/Unknown | 136 (45) | 37 (43) | 99 (46) |

| White | 168 (55) | 50 (57) | 118 (54) |

| Age, Years, Mean (SD) | 14.23 (4.84) | 19.93 (1.85) | 11.94 (3.63) |

| Clinical | |||

| Height, Inches, Mean (SD) | 61.51 (7.71) | 66.68 (3.95) | 59.47 (7.88) |

| Weight, kg, (Mean (SD)) | 56.56 (21.86) | 73.26 (17.13) | 50.07 (20.00) |

| BMI, kg/m2, (Mean (SD)) b | - | 25.46 (5.12) | - |

| Systolic BP a, mmHg, Mean (SD) | 117.44 (9.27) | 119.30 (10.06) | 116.01 (8.38) |

| Diastolic BP a, mmHg, Mean (SD) | 67.69 (8.62) | 70.43 (8.45) | 65.59 (8.18) |

| Elevated BP | 56 (19) | 27 (32) | 29 (14) |

| Normal BP | 208 (71) | 37 (44) | 171 (81) |

| Stage 1 Hypertension | 30 (10) | 20 (24) | 10 (5) |

| Stage 2 Hypertension | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) |

| HbA1c, %, Mean (SD) | 7.80 (1.54) | 7.66 (1.61) | 7.86 (1.51) |

| <7 | 88 (31) | 28 (35) | 60 (30) |

| 7 ≤ & < 9 | 141 (50) | 40 (50) | 101 (50) |

| ≥9 | 54 (19) | 12 (15) | 42 (20) |

| HDL, mg/dL, Mean (SD) | 60.66 (13.88) | 59.84 (15.35) | 60.98 (13.30) |

| ≤35 | 5 (2) | 1 (1) | 4 (2) |

| >35 | 282 (98) | 79 (99) | 203 (98) |

| LDL, mg/dL, Mean (SD) | 91.55 (27.02) | 90.35 (31.01) | 92.01 (25.38) |

| <100 | 178 (62) | 48 (60) | 130 (63) |

| 100 ≤ & ≤ 129 | 89 (31) | 24 (30) | 65 (31) |

| >130 | 20 (7) | 8 (10) | 12 (6) |

| Physical Activity | |||

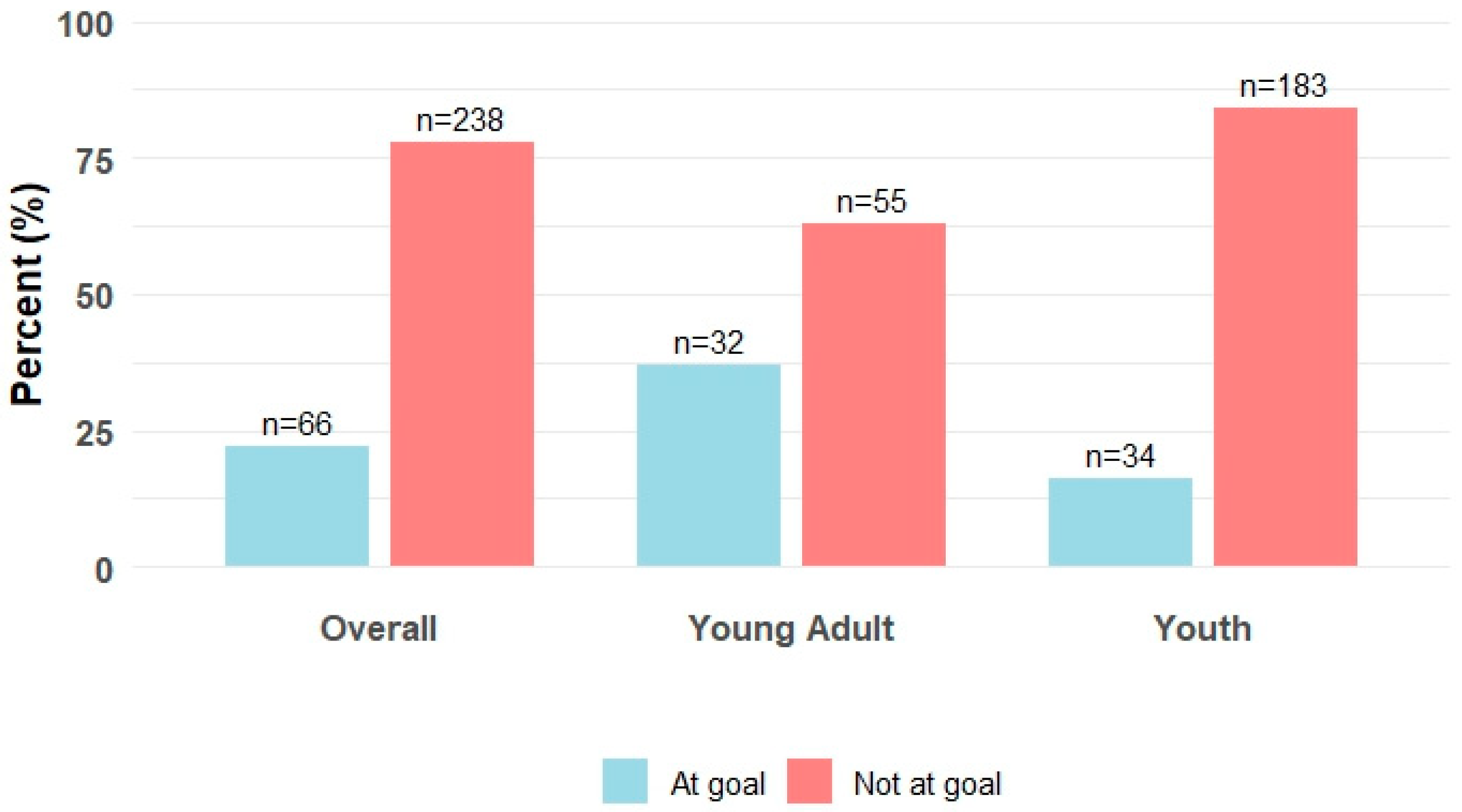

| PA Goal Attainment | |||

| Not at Goal | 238 (78) | 55 (63) | 183 (84) |

| At Goal | 66 (22) | 32 (37) | 34 (16) |

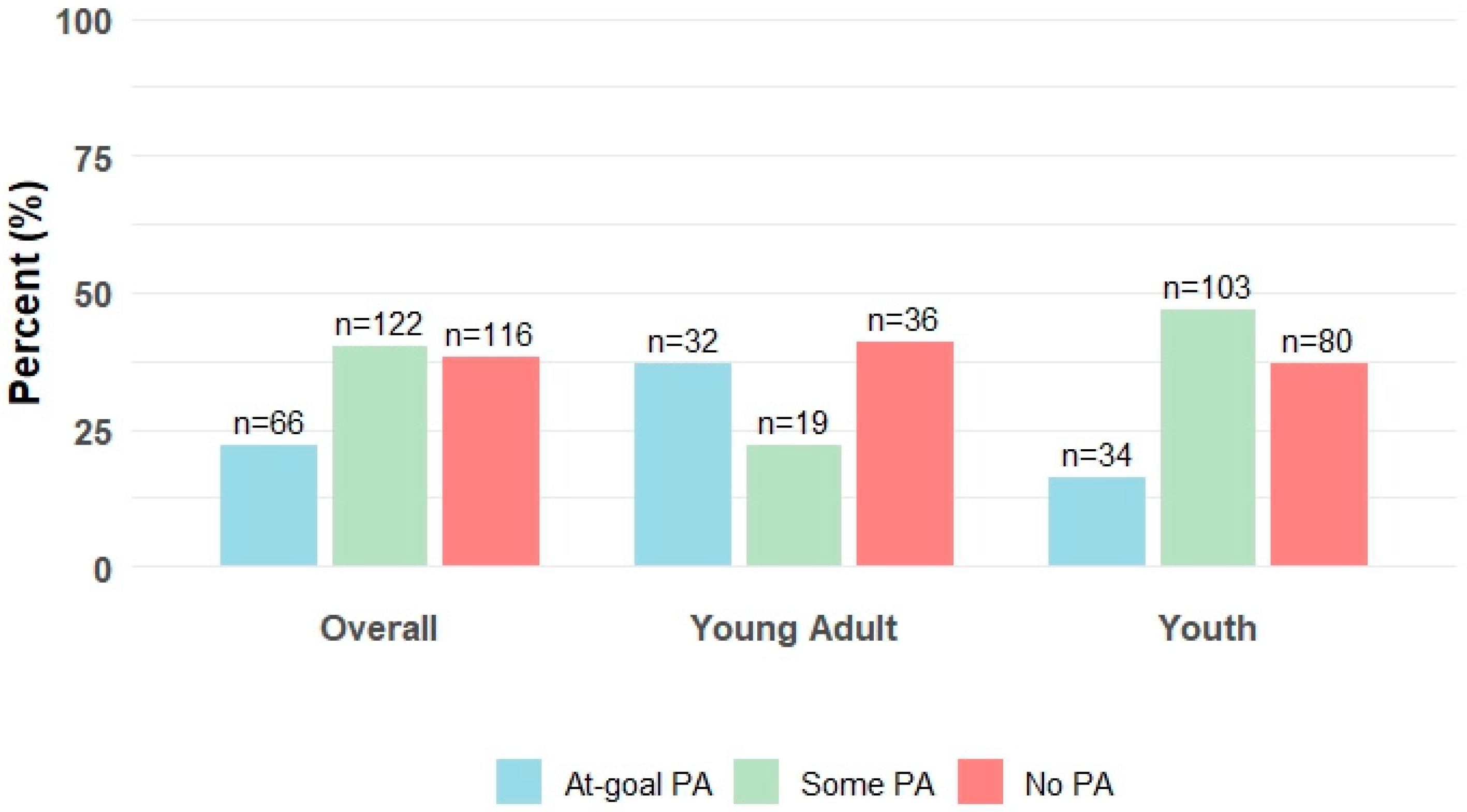

| PA Level | |||

| No PA | 116 (38) | 36 (41) | 80 (37) |

| Some PA | 122 (40) | 19 (22) | 103 (47) |

| At-Goal PA | 66 (22) | 32 (37) | 34 (16) |

| Technology Use | |||

| CGM Use | 208 (89) | 55 (86) | 153 (91) |

| Insulin Pump Use | 180 (77) | 52 (80) | 128 (76) |

| Tech Use | |||

| No Tech | 86 (28) | 27 (31) | 59 (27) |

| CGM Only | 38 (13) | 8 (9) | 30 (14) |

| PUMP Only | 10 (3) | 5 (6) | 5 (2) |

| Use Both | 170 (56) | 47 (54) | 123 (57) |

| Characteristic | Not at Goal, N = 238 | At Goal, N = 66 | pa | Effect Size c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Demographic | ||||

| Sex | 0.096 | 0.09 | ||

| Female | 120 (50) | 25 (38) | ||

| Male | 118 (50) | 41 (62) | ||

| Race | 0.774 | <0.01 | ||

| Underrepresented | 108 (45) | 28 (42) | ||

| White | 130 (55) | 38 (58) | ||

| Technology Use | ||||

| CGM Use (Yes) | 165 (88) d | 43 (93) | 0.425 | 0.02 |

| PUMP Use (Yes) | 145 (78) | 35 (76) | 0.989 | <0.01 |

| Tech Use | 0.584 | <0.01 | ||

| No Tech | 64 (27) | 22 (33) | ||

| CGM Only | 29 (12) | 9 (14) | ||

| PUMP Use | 9 (4) | 1 (1) | ||

| Use Both | 136 (57) | 34 (52) | ||

| Clinical | ||||

| BMI, kg/m2, (Mean (SD)) d | 25.39 (5.54) | 25.59 (4.38) | 0.850 | 0.04 |

| HbA1c, %, Mean (SD) | 7.80 (1.53) | 7.83 (1.56) | 0.871 | 0.02 |

| HDL, mg/dL, Mean (SD) | 60.37 (13.49) | 61.74 (15.32) | 0.528 | 0.10 |

| LDL, mg/dL, Mean (SD) | 93.65 (25.17) | 83.92 (31.95) | 0.029 | 0.36 |

| Systolic BP b, mmHg, Mean (SD) | 116.62 (9.36) | 119.58 (8.76) | 0.039 | 0.32 |

| Diastolic BP b, mmHg, Mean (SD) | 67.45 (7.76) | 68.33 (10.58) | 0.576 | 0.10 |

| Characteristic | No PA, N = 116 | Some PA, N = 122 | At-Goal PA, N = 66 | p a | Effect Size c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Demographic | |||||

| Sex | 0.159 | 0.07 | |||

| Female | 61 (53) | 59 (48) | 25 (38) | ||

| Male | 55 (47) | 63 (52) | 41 (62) | ||

| Race | |||||

| Underrepresented | 50 (43) | 58 (48) | 28 (42) | 0.720 | <0.01 |

| White | 55 (47) | 63 (52) | 38 (58) | ||

| Technology use | |||||

| CGM use (yes) | 85 (88) | 80 (89) | 43 (93) | 0.566 | <0.01 |

| PUMP use (yes) | 74 (75) | 71 (81) | 35 (76) | 0.613 | <0.01 |

| Technology use | |||||

| No tech | 25 (22) | 39 (32) | 22 (33) | 0.357 | 0.03 |

| CGM only | 17 (15) | 12 (10) | 9 (14) | ||

| PUMP only | 6 (5) | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | ||

| Use both | 68 (59) | 68 (56) | 34 (52) | ||

| Clinical | |||||

| BMI, kg/m2, (mean (SD)) d | 25.22 (5.48) | 25.70 (5.77) | 25.59 (4.38) | 0.933 | <0.01 |

| HbA1c, %, mean (SD) | 7.84 (1.53) | 7.76 (1.54) | 7.83 (1.56) | 0.912 | <0.01 |

| HDL, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 58.71 (12.72) | 61.95 (14.06) | 61.74 (15.32) | 0.171 | 0.01 |

| LDL, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 92.99 (26.44) | 94.28 (23.99) | 83.92 (31.95) | 0.040 | 0.02 |

| Post Hoc Tukey HSD test | Mean diff | p-Adjusted | |||

| LDL (some PA–at-goal PA) | 10.36 | 0.039 | |||

| Systolic blood pressure b, mmHg, mean (SD) | 116.47 (9.49) | 116.76 (9.29) | 119.58 (8.76) | 0.130 | 0.02 |

| Diastolic blood pressure b, mmHg, mean (SD) | 67.67 (7.27) | 67.23 (8.29) | 68.33 (10.58) | 0.778 | <0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McCarthy, M.M.; Ilkowitz, J.; Hu, J.; Gallagher, M.P. Implementing the Physical Activity Vital Sign in a Pediatric Diabetes Center. Diabetology 2025, 6, 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120157

McCarthy MM, Ilkowitz J, Hu J, Gallagher MP. Implementing the Physical Activity Vital Sign in a Pediatric Diabetes Center. Diabetology. 2025; 6(12):157. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120157

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcCarthy, Margaret M., Jeniece Ilkowitz, Jinyu Hu, and Mary Pat Gallagher. 2025. "Implementing the Physical Activity Vital Sign in a Pediatric Diabetes Center" Diabetology 6, no. 12: 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120157

APA StyleMcCarthy, M. M., Ilkowitz, J., Hu, J., & Gallagher, M. P. (2025). Implementing the Physical Activity Vital Sign in a Pediatric Diabetes Center. Diabetology, 6(12), 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120157