Advances in Succinoglycan-Based Biomaterials: Structural Features, Functional Derivatives, and Multifunctional Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Overview of Succinoglycan and Its Biosynthesis

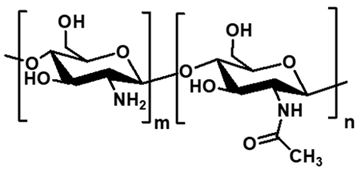

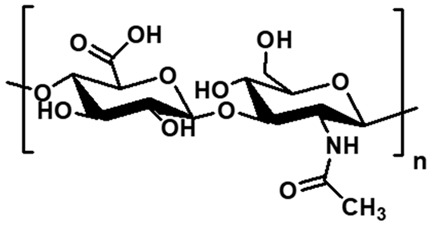

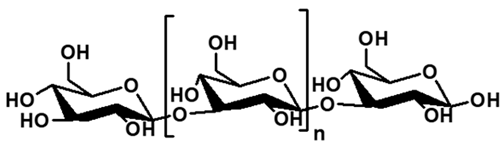

2.1. Comparative Overview of Polysaccharides and Succinoglycan

| Polysaccharide | Source | Structure | Components | Molecular Weight (Da) | Main Properties | Main Application | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starch | Plants (corn, potato, cassava, rice) |  | Amylose, Amylopectin | ~1 × 105–1 × 107 | Thermo-gelatinization, viscoelasticity, biodegradability | Hydrogels, biodegradable films, packaging materials, drug delivery | [60,61,62] |

| Pectin | Plants (Citrus peel, apple pomace) |  | Galacturonic acid | ~5 × 104–3 × 105 | pH-responsive gelation, Ca2+ chelation, mucoadhesiveness | Hydrogels, mucoadhesive films, wound dressing, drug delivery | [46,63] |

| Cellulose | Plants, bacteria (Acetobacter sp.) |  | Glucose | ~1 × 105–106 | High crystallinity, water-insoluble, high mechanical strength | Films, scaffolds, drug delivery, wound dressing | [64,65,66] |

| Alginate | Pseudomonas sp., Azotobacter sp., brown algae |  | Mannuronic acid, Glucuronic acid | <1.3 × 106 | Anionic Hydrocolloid, biocompatibility, metal chelation | Food hydrocolloid, wound dressing, drug release systems | [67,68,69] |

| Chitosan | Crustacean shells (chitin deacetylation) |  | Glucosamine, N-acetylglucosamine | 1 × 105–1 × 106 | Cationic, antimicrobial, primary amine based crosslinking | Antibacterial component, drug delivery, wound healing, tissue engineering | [70,71,72] |

| Hyaluronic acid | Diplococcus sp., Streptococcus sp., Staphylococcus sp. |  | Glucuronic acid, N-acetylglucosamine | ~2 × 105 | Hydration capacity, viscoelastic behavior, biocompatibility | Drug delivery, wound healing scaffolds, tissue engineering | [73,74] |

| Xanthan | Xanthomonas sp. |  | Glucose, Mannose, Glucuronic acid, Acetate, Pyruvate | <5 × 106 | Anionic, High viscosity, pH/salt stability, Hydrocolloid | Food thickener, oil recovery, pharmaceuticals | [75,76,77] |

| Gellan gum | Sphingomonas paucimobilis |  | Glucose, Rhamnose, Glucuronic acid, Acetate | ~5 × 105 | Anionic, Thermo-reversible gelation, pH stability | Food, pharmaceuticals, electrophoresis gels | [78,79,80] |

| Pullulan | Aureobasidium sp. |  | Glucose | 4.0 × 104–2.0 × 106 | Water-soluble, film-forming, adhesive, biocompatible, non-toxic | Edible films, drug delivery, tissue engineering, food coatings, biodegradable packaging | [81,82] |

| Curdlan | Agrobacterium sp. |  | Glucose | 1.0 × 105–3.6 × 106 | Water-insoluble, thermogelation, high mechanical strength, Biocompatible | Food gelation, biomedical scaffolds, drug delivery, wound dressing, tissue engineering | [83,84] |

| FucoPol | Enterobacter A47 |  | Fucose, Galactose, Glucose, Glucuronic acid | 1.5 × 106 | Emulsifying, film-forming, biocompatible | Emulsifiers, wound dressing, coatings | [85,86] |

| Succinoglycan | Rhizobium sp., Agrobacterium sp., |  | Glucose, Galactose, Acetate, Pyruvate, Succinate | LMW < 5 × 103, HMW > 1 × 106 | High viscosity, anionic, stable under acidic conditions | Cosmetics, food thickener, emulsifier, stabilizer, biofilms | [87,88] |

2.2. Biosynthesis of Succinoglycan Mediated by the Exo Gene Cluster

2.3. Regulation of Succinoglycan Biosynthesis

2.4. Molecular Weight Distribution Under Different Biosynthetic Conditions

2.5. Production and Purification of Succinoglycan from Bacterial Cultures

3. Structural Features and Physicochemical Properties of Succinoglycan

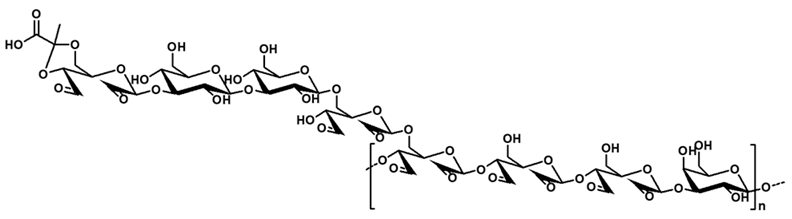

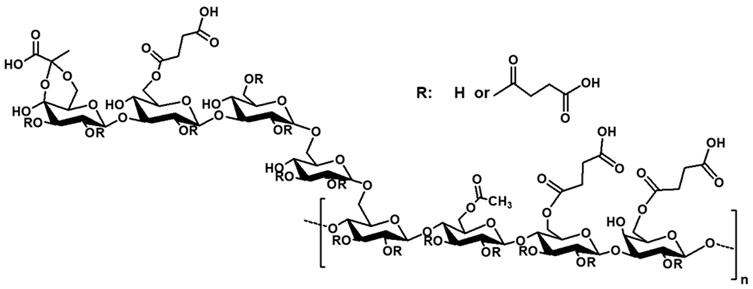

3.1. Structural Characteristics of Succinoglycan

3.2. Rheological Properties of Succinoglycan

3.3. Thermal Stability of Succinoglycan

3.4. Antibacterial Activity of Succinoglycan

3.5. Antioxidant Activity of Succinoglycan

3.6. Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Succinoglycan

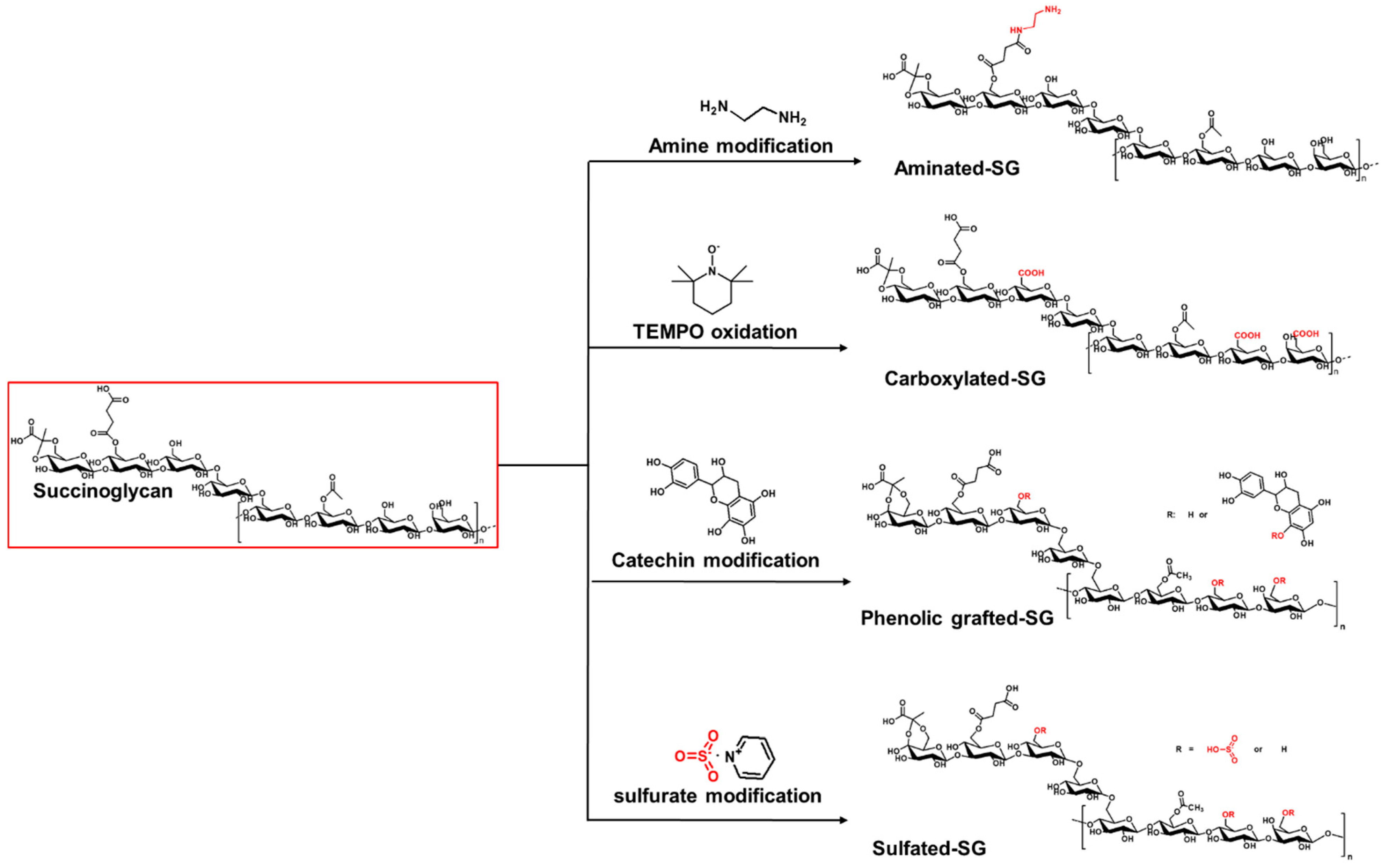

4. Modification of Succinoglycan and Its Derivatives

4.1. Periodate Oxidation of Succinoglycan

4.2. Succinylation of Succinoglycan

4.3. Carboxyethylation of Succinoglycan

4.4. Phenolic Grafting of Succinoglycan

4.5. Alkaline Treatment of Succinoglycan for Riclin Formation

5. Succinoglycan-Based Multifunctional Films and Hydrogels

5.1. Succinoglycan-Based Films

5.2. Succinoglycan-Based Hydrogels

6. Challenges and Future Perspectives

6.1. Amination of Succinoglycan

6.2. TEMPO Oxidation of Succinoglycan

6.3. Sulfation of Succinoglycan

6.4. Phenolic Radical Grafting of Succinoglycan

6.5. Succinoglycan-Based Adhesive Materials

6.6. Bioplastic Applications of Succinoglycan

6.7. Potential Regulatory and Huddle of Succinoglycan for Application

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Levin, M.; Tang, Y.; Eisenbach, C.D.; Valentine, M.T.; Cohen, N. Understanding the response of poly (ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) hydrogel networks: A statistical mechanics-based framework. Macromolecules 2024, 57, 7074–7086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebeish, A.; Farag, S.; Sharaf, S.; Shaheen, T.I. Thermal responsive hydrogels based on semi interpenetrating network of poly (NIPAm) and cellulose nanowhiskers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 102, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, R.D.; Lopes, E.R.; Ramos, E.M.; de Oliveira, T.V.; de Oliveira, C.P. Active packaging: Development and characterization of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and nitrite film for pork preservation. Food Chem. 2024, 437, 137811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Du, P.; Sun, L.; Yu, Z.; Song, S.; Yin, J.; Ma, X.; Jing, C. Preparation of PU/fibrin vascular scaffold with good biomechanical properties and evaluation of its performance in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 8697–8715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, L.K.; Huebner, P.; Fisher, M.B.; Spang, J.T.; Starly, B.; Shirwaiker, R.A. 3D-bioprinting of polylactic acid (PLA) nanofiber–alginate hydrogel bioink containing human adipose-derived stem cells. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 2, 1732–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, J.; Kasprzyk, P. Thermoplastic polyurethanes derived from petrochemical or renewable resources: A comprehensive review. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2018, 58, E14–E35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delidovich, I.; Hausoul, P.J.; Deng, L.; Pfützenreuter, R.; Rose, M.; Palkovits, R. Alternative monomers based on lignocellulose and their use for polymer production. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 1540–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satchanska, G.; Davidova, S.; Petrov, P.D. Natural and synthetic polymers for biomedical and environmental applications. Polymers 2024, 16, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samir, A.; Ashour, F.H.; Hakim, A.A.; Bassyouni, M. Recent advances in biodegradable polymers for sustainable applications. npj Mater. Degrad. 2022, 6, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Fu, Y.; Jiao, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, M.; Yong, Y.-C.; Liu, J. A structure-functionality insight into the bioactivity of microbial polysaccharides toward biomedical applications: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 335, 122078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullaev, S.S.; Althomali, R.H.; Abdu Musad Saleh, E.; Robertovich, M.R.; Sapaev, I.; Romero-Parra, R.M.; Alsaab, H.O.; Gatea, M.A.; Fenjan, M.N. Synthesis of novel antibacterial and biocompatible polymer nanocomposite based on polysaccharide gum hydrogels. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurunathan, M.K.; Navasingh, R.J.H.; Selvam, J.D.R.; Čep, R. Development and characterization of starch bioplastics as a sustainable alternative for packaging. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marichelvam, M.; Kanadakodeeeswaran, K.; Dheenesh, D.; Easwarapandiyan, S.; Lokeshkumar, B. Developing eco-friendly bio-plastics from natural sources for sustainable packaging. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2025, 46, 102105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Cheng, Q.; Long, Y.; Xu, C.; Fang, H.; Chen, Y.; Dai, H. A chitosan based scaffold with enhanced mechanical and biocompatible performance for biomedical applications. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2020, 181, 109322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendis, H.C.; Madzima, T.F.; Queiroux, C.; Jones, K.M. Function of succinoglycan polysaccharide in Sinorhizobium meliloti host plant invasion depends on succinylation, not molecular weight. mBio 2016, 7, e00606-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junges, R.; Salvadori, G.; Shekhar, S.; Åmdal, H.A.; Periselneris, J.N.; Chen, T.; Brown, J.S.; Petersen, F.C. A quorum-sensing system that regulates Streptococcus pneumoniae biofilm formation and surface polysaccharide production. mSphere 2017, 2, e00324-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yodsanga, S.; Poeaim, S.; Chantarangsu, S.; Swasdison, S. Investigation of Biodegradation and Biocompatibility of Chitosan–Bacterial Cellulose Composite Scaffold for Bone Tissue Engineering Applications. Cells 2025, 14, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, M.; Mastroianni, G.; Bilotti, E.; Zhang, H.; Papageorgiou, D.G. Biodegradable starch-based nanocomposite films with exceptional water and oxygen barrier properties. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 11056–11066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewkumsan, P.; Gavahian, M.; Tseng, W.-T.; Guo, J.-H. Structural and immunomodulatory properties of bioactive polysaccharide from solid-state fermented brown rice with Antrodia cinnamomea mycelia. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods 2025, 17, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casillo, A.; Fabozzi, A.; Russo Krauss, I.; Parrilli, E.; Biggs, C.I.; Gibson, M.I.; Lanzetta, R.; Appavou, M.-S.; Radulescu, A.; Tutino, M.L. Physicochemical approach to understanding the structure, conformation, and activity of mannan polysaccharides. Biomacromolecules 2021, 22, 1445–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, J.; Azhar, S.; Lawoko, M.; Lindström, M.; Vilaplana, F.; Wohlert, J.; Henriksson, G. The structure of galactoglucomannan impacts the degradation under alkaline conditions. Cellulose 2019, 26, 2155–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, K.; Xu, D.; Gong, S.; Lu, Y.-T.; Vana, P.; Groth, T.; Zhang, K. Thermoresponsive hydrogels with sulfated polysaccharide-derived copolymers: The effect of carbohydrate backbones on the responsive and mechanical properties. Cellulose 2023, 30, 8355–8368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Donovan, M.; Foucher, A.; Schultze, X.; Lecommandoux, S. Multivalent and multifunctional polysaccharide-based particles for controlled receptor recognition. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelhoso, I. Polysaccharide Films/Membranes for Food and Industrial Applications. Polysaccharides 2025, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.; Cardoso, L.; Da Costa, A.M.R.; Grenha, A. Biocompatibility and stability of polysaccharide polyelectrolyte complexes aimed at respiratory delivery. Materials 2015, 8, 5647–5670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossla, E.; Tonndorf, R.; Bernhardt, A.; Kirsten, M.; Hund, R.-D.; Aibibu, D.; Cherif, C.; Gelinsky, M. Electrostatic flocking of chitosan fibres leads to highly porous, elastic and fully biodegradable anisotropic scaffolds. Acta Biomater. 2016, 44, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira-Costa, B.E.; Andrade, C.T. Natural polymers used in edible food packaging—History, function and application trends as a sustainable alternative to synthetic plastic. Polysaccharides 2021, 3, 32–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Chang, X.; Fu, X.; Kong, H.; Yu, Y.; Xu, H.; Shan, Y.; Ding, S. Fabrication and characterization of pullulan-based composite films incorporated with bacterial cellulose and ferulic acid. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 219, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, A.; Ramos, A.; Domingues, F.; Luís, Â. Pullulan-Tween 40 emulsified films containing geraniol: Production and characterization as potential food packaging materials. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2024, 250, 1721–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.-P.; Walker, G.C. Succinoglycan is required for initiation and elongation of infection threads during nodulation of alfalfa by Rhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 5183–5191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuber, T.L.; Walker, G.C. Biosynthesis of succinoglycan, a symbiotically important exopolysaccharide of Rhizobium meliloti. Cell 1993, 74, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, S.; Wood, K.; Reuhs, B.L. Structural analysis of succinoglycan oligosaccharides from Sinorhizobium meliloti strains with different host compatibility phenotypes. J. Bacteriol. 2013, 195, 2032–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, K.M. Increased production of the exopolysaccharide succinoglycan enhances Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021 symbiosis with the host plant Medicago truncatula. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 4322–4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.-X.; Wang, Y.; Pellock, B.; Walker, G.C. Structural characterization of the symbiotically important low-molecular-weight succinoglycan of Sinorhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 6788–6796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, L.R.; Linker, A.; Impallomeni, G. Structure of succinoglycan from an infectious strain of Agrobacterium radiobacter. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2000, 27, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, U.; Banerjee, A.; Bandopadhyay, R. Structural and functional properties, biosynthesis, and patenting trends of bacterial succinoglycan: A review. Indian J. Microbiol. 2017, 57, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Kim, Y.; Hong, I.; Kim, M.; Jung, S. Fabrication of flexible pH-responsive agarose/succinoglycan hydrogels for controlled drug release. Polymers 2021, 13, 2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Wang, X.; Kong, C.; Chen, S.; Hu, C.; Zhang, J. Hydrogel based on riclin cross-linked with polyethylene glycol diglycidyl ether as a soft filler for tissue engineering. Biomacromolecules 2024, 25, 1119–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, N.; Atif, M. Polysaccharides based biopolymers for biomedical applications: A review. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2024, 35, e6203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yermagambetova, A.; Tazhibayeva, S.; Takhistov, P.; Tyussyupova, B.; Tapia-Hernández, J.A.; Musabekov, K. Microbial Polysaccharides as Functional Components of Packaging and Drug Delivery Applications. Polymers 2024, 16, 2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostag, M.; El Seoud, O.A. Sustainable biomaterials based on cellulose, chitin and chitosan composites-A review. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2021, 2, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipón, J.; Ramírez, K.; Morales, J.; Díaz-Calderón, P. Rheological and thermal study about the gelatinization of different starches (potato, wheat and waxy) in blend with cellulose nanocrystals. Polymers 2022, 14, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paes, S.S.; Yakimets, I.; Mitchell, J.R. Influence of gelatinization process on functional properties of cassava starch films. Food Hydrocoll. 2008, 22, 788–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koev, T.T.; Muñoz-García, J.C.; Iuga, D.; Khimyak, Y.Z.; Warren, F.J. Structural heterogeneities in starch hydrogels. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 249, 116834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, N.S.; Olawuyi, I.F.; Lee, W.Y. Pectin hydrogels: Gel-forming behaviors, mechanisms, and food applications. Gels 2023, 9, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szekalska, M.; Czajkowska-Kośnik, A.; Maciejewski, B.; Misztalewska-Turkowicz, I.; Wilczewska, A.Z.; Bernatoniene, J.; Winnicka, K. Mucoadhesive alginate/pectin films crosslinked by calcium carbonate as carriers of a model antifungal drug—Posaconazole. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farshidfar, N.; Iravani, S.; Varma, R.S. Alginate-based biomaterials in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomić, S.L.; Babić Radić, M.M.; Vuković, J.S.; Filipović, V.V.; Nikodinovic-Runic, J.; Vukomanović, M. Alginate-based hydrogels and scaffolds for biomedical applications. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Q.; Zheng, C.; Chen, W.; Sun, N.; Gao, Q.; Liu, J.; Hu, F.; Pimpi, S.; Yan, X.; Zhang, Y. Current challenges and future applications of antibacterial nanomaterials and chitosan hydrogel in burn wound healing. Mater. Adv. 2022, 3, 6707–6727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirupathi, K.; Raorane, C.J.; Ramkumar, V.; Ulagesan, S.; Santhamoorthy, M.; Raj, V.; Krishnakumar, G.S.; Phan, T.T.V.; Kim, S.-C. Update on chitosan-based hydrogels: Preparation, characterization, and its antimicrobial and antibiofilm applications. Gels 2022, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, B.; Peng, D.; Nie, X.; Wang, J.; Yu, C.-Y.; Wei, H. Hyaluronic acid-based injectable hydrogels for wound dressing and localized tumor therapy: A review. Adv. NanoBiomed Res. 2022, 2, 2200124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martorana, A.; Pitarresi, G.; Palumbo, F.S.; Barberi, G.; Fiorica, C.; Giammona, G. Correlating rheological properties of a gellan gum-based bioink: A study of the impact of cell density. Polymers 2022, 14, 1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, N.-M.N.; Le-Vinh, B.; Friedl, J.D.; Jalil, A.; Kali, G.; Bernkop-Schnürch, A. Polyaminated pullulan, a new biodegradable and cationic pullulan derivative for mucosal drug delivery. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 282, 119143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.A.; Yadav, M.P.; Sharma, B.K.; Qi, P.X.; Jin, T.Z. Biodegradable food packaging films using a combination of hemicellulose and cellulose derivatives. Polymers 2024, 16, 3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wypij, M.; Rai, M.; Zemljič, L.F.; Bračič, M.; Hribernik, S.; Golińska, P. Pullulan-based films impregnated with silver nanoparticles from the Fusarium culmorum strain JTW1 for potential applications in the food industry and medicine. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1241739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, S.; Mert, B.; Campanella, O.H.; Reuhs, B. Chemical and rheological properties of bacterial succinoglycan with distinct structural characteristics. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 76, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andhare, P.; Delattre, C.; Pierre, G.; Michaud, P.; Pathak, H. Characterization and rheological behaviour analysis of the succinoglycan produced by Rhizobium radiobacter strain CAS from curd sample. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 64, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stredansky, M.; Conti, E.; Bertocchi, C.; Matulova, M.; Zanetti, F. Succinoglycan production by Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 1998, 85, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glucksmann, M.; Reuber, T.; Walker, G. Genes needed for the modification, polymerization, export, and processing of succinoglycan by Rhizobium meliloti: A model for succinoglycan biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 1993, 175, 7045–7055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bora, A.; Sarmah, D.; Rather, M.A.; Mandal, M.; Karak, N. Nanocomposite of starch, gelatin and itaconic acid-based biodegradable hydrogel and ZnO/cellulose nanofiber: A pH-sensitive sustained drug delivery vehicle. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 256, 128253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troncoso, V.T.; Hernández-Hernández, O.; Alvarez, M.V.; Ponce, A.G.; Mendieta, J.R.; Gutiérrez, T.J. Organocatalytically salicylated starch-based food packaging obtained via reactive extrusion/thermo-molding. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 320, 146116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Wu, M.; Luo, L.; Lu, R.; Zhu, J.; Li, Y.; Cai, Y.; Xiang, H.; Song, C.; Yu, B. Incorporating iron oxide nanoparticles in polyvinyl alcohol/starch hydrogel membrane with biochar for enhanced slow-release properties of compound fertilizers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 348, 122834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvanian, M.; Ng, S.-F.; Alavi, T.; Ahmad, W. In-vivo evaluation of Alginate-Pectin hydrogel film loaded with Simvastatin for diabetic wound healing in Streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 171, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Zandraa, O.; Mudenur, C.; Saha, N.; Sáha, P.; Mandal, B.; Katiyar, V. Composite scaffolds based on bacterial cellulose for wound dressing application. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2022, 5, 3722–3733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Wang, B.; Bai, S.; Fan, B.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wang, F. Structure regulation of oxidized soybean cellulose nanocrystals/poly-acrylamide hydrogel and its application potential in wound dressing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 281, 136541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishparenok, A.N.; Koroleva, S.A.; Dobryakova, N.V.; Gladilina, Y.A.; Gromovykh, T.I.; Solopov, A.B.; Kudryashova, E.V.; Zhdanov, D.D. Bacterial cellulose films for L-asparaginase delivery to melanoma cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 276, 133932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thu, H.-E.; Zulfakar, M.H.; Ng, S.-F. Alginate based bilayer hydrocolloid films as potential slow-release modern wound dressing. Int. J. Pharm. 2012, 434, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, S.; Bai, X.; Zhu, Y.; Gao, X.; Balah, M.A.; Mao, X.; Jiang, H. Eco-friendly food packaging films: Sustainable alginate extraction from Sargassum via enzymatic engineering. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 171, 111760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazemoroaia, M.; Bagheri, F.; Mirahmadi-Zare, S.Z.; Eslami-Kaliji, F.; Derakhshan, A. Asymmetric natural wound dressing based on porous chitosan-alginate hydrogel/electrospun PCL-silk sericin loaded by 10-HDA for skin wound healing: In vitro and in vivo studies. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 668, 124976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sethi, S.; Mahajan, P.; Thakur, S.; Sharma, N.; Singh, N.; Kumar, A.; Kaur, A.; Kaith, B.S. Design and evaluation of fluorescent chitosan-starch hydrogel for drug delivery and sensing applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 274, 133486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Lu, L.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, Q.; Luo, L.; Ma, D.; Wang, W.; Zhang, W. Dual-crosslinked cirsiumsetosum polysaccharide/quaternary chitosan self-healing hydrogel promotes wound healing. Carbohydr. Res. 2025, 556, 109616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Sun, M.; Lu, X.; Xu, K.; Yu, M.; Yang, H.; Yin, J. A 3D printable gelatin methacryloyl/chitosan hydrogel assembled with conductive PEDOT for neural tissue engineering. Compos. Part B Eng. 2024, 273, 111241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabizadeh, Z.; Nasrollahzadeh, M.; Heidari, F.; Nasrabadi, D. A drug-loaded nano chitosan/hyaluronic acid hydrogel system as a cartilage tissue engineering scaffold for drug delivery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 283, 137314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Hu, H.; Hu, M.; Ji, S.; Lei, T.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Dong, W.; Teng, C.; Wei, W. A nano-composite hyaluronic acid-based hydrogel efficiently antibacterial and scavenges ROS for promoting infected diabetic wound healing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 334, 122064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadde, E.K.; Mossel, B.; Chen, J.; Prakash, S. The safety and efficacy of xanthan gum-based thickeners and their effect in modifying bolus rheology in the therapeutic medical management of dysphagia. Food Hydrocoll. Health 2021, 1, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoumrassi-Barr, S.; Aliouche, D. A rheological study of xanthan polymer for enhanced oil recovery. J. Macromol. Sci. Part B 2016, 55, 793–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadav, M.; Pooja, D.; Adams, D.J.; Kulhari, H. Advances in xanthan gum-based systems for the delivery of therapeutic agents. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Lin, J.; Wang, W.; Li, S. Biopolymers produced by Sphingomonas strains and their potential applications in petroleum production. Polymers 2022, 14, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Giri, T.K. Hydrogels based on gellan gum in cell delivery and drug delivery. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 56, 101586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Z.; Wu, X.; Sun, X.; Huang, X.; Zhuo, X.; Wang, H.; Komarneni, S.; Zhang, K.; Ni, Z.; Hu, G. Gellan gum and pullulan-based films with triple functionalities of antioxidant, antibacterial and freshness indication properties for food packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 134825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.S.; Kaur, N.; Rana, V.; Kennedy, J.F. Recent insights on applications of pullulan in tissue engineering. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 153, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedro, S.N.; Valente, B.F.; Vilela, C.; Oliveira, H.; Almeida, A.; Freire, M.G.; Silvestre, A.J.; Freire, C.S. Switchable adhesive films of pullulan loaded with a deep eutectic solvent-curcumin formulation for the photodynamic treatment of drug-resistant skin infections. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 22, 100733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurzynska, A.; Klimek, K.; Swierzycka, I.; Palka, K.; Ginalska, G. Porous curdlan-based hydrogels modified with copper ions as potential dressings for prevention and management of bacterial wound infection—An in vitro assessment. Polymers 2020, 12, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangolim, C.S.; Silva, T.T.d.; Fenelon, V.C.; Koga, L.N.; Ferreira, S.B.d.S.; Bruschi, M.L.; Matioli, G. Description of recovery method used for curdlan produced by Agrobacterium sp. IFO 13140 and its relation to the morphology and physicochemical and technological properties of the polysaccharide. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, S.; Freitas, F. Formulation of the polysaccharide FucoPol into novel emulsified creams with improved physicochemical properties. Molecules 2022, 27, 7759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, S.; Torres, C.A.; Sevrin, C.; Grandfils, C.; Reis, M.A.; Freitas, F. Extraction of the bacterial extracellular polysaccharide FucoPol by membrane-based methods: Efficiency and impact on biopolymer properties. Polymers 2022, 14, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.-p.; Kim, Y.; Hu, Y.; Jung, S. Bacterial succinoglycans: Structure, physical properties, and applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delani, T.C.d.O.; Miyoshi, J.H.; Nascimento, M.G.; Sampaio, A.R.; Palácios, R.d.S.; Sato, F.; Reichembach, L.H.; Petkowicz, C.L.d.O.; Ruiz, S.P.; Matioli, G. Evaluation of the biosynthesis, structural and rheological characterization of succinoglycan obtained from a formulation composed of whole and deproteinized whey. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 43, e105922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaudi, L.V.; González, J.E. The low-molecular-weight fraction of exopolysaccharide II from Sinorhizobium meliloti is a crucial determinant of biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 7216–7224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, S.A.; Gurich, N.; Feeney, M.A.; Gonzalez, J.E. The ExpR/Sin quorum-sensing system controls succinoglycan production in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 7077–7088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomlinson, A.D.; Ramey-Hartung, B.; Day, T.W.; Merritt, P.M.; Fuqua, C. Agrobacterium tumefaciens ExoR represses succinoglycan biosynthesis and is required for biofilm formation and motility. Microbiology 2010, 156, 2670–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, G.M.; Walker, G.C. The succinyl and acetyl modifications of succinoglycan influence susceptibility of succinoglycan to cleavage by the Rhizobium meliloti glycanases ExoK and ExsH. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 4184–4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skorupska, A.; Janczarek, M.; Marczak, M.; Mazur, A.; Król, J. Rhizobial exopolysaccharides: Genetic control and symbiotic functions. Microb. Cell Factories 2006, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, J.; Sieber, V.; Rehm, B. Bacterial exopolysaccharides: Biosynthesis pathways and engineering strategies. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, J.P.; Geddes, B.A.; Oresnik, I.J. Succinoglycan production contributes to acidic pH tolerance in Sinorhizobium meliloti Rm1021. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2017, 30, 1009–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemeyer, D.; Becker, A. The molecular weight distribution of succinoglycan produced by Sinorhizobium meliloti is influenced by specific tyrosine phosphorylation and ATPase activity of the cytoplasmic domain of the ExoP protein. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183, 5163–5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jeong, J.-p.; Kim, Y.; Jung, S. Physicochemical and Rheological Properties of Succinoglycan Overproduced by Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021 Mutant. Polymers 2024, 16, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.-P.; Walker, G.C. Succinoglycan production by Rhizobium meliloti is regulated through the ExoS-ChvI two-component regulatory system. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, S.-Y.; Luo, L.; Har, K.J.; Becker, A.; RübErg, S.; Yu, G.-Q.; Zhu, J.-B.; Cheng, H.-P. Sinorhizobium meliloti ExoR and ExoS proteins regulate both succinoglycan and flagellum production. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 6042–6049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, A.; Ruberg, S.; Baumgarth, B.; Bertram-Drogatz, P.A.; Quester, I.; Puhler, A. Regulation of succinoglycan and galactoglucan biosynthesis in Sinorhizobium meliloti. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002, 4, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyraud, A.; Courtois, J.; Dantas, L.; Colin-Morel, P.; Courtois, B. Structural characterization and rheological properties of an extracellular glucuronan produced by a Rhizobium meliloti M5N1 mutant strain. Carbohydr. Res. 1993, 240, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Yang, L.; Tian, J.; Huang, L.; Huang, D.; Zhang, W.; Xie, F.; Niu, Y.; Jin, M.; Jia, C. Characterization and rheological properties analysis of the succinoglycan produced by a high-yield mutant of Rhizobium radiobacter ATCC 19358. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 166, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, J.E.; Semino, C.E.; Wang, L.-X.; Castellano-Torres, L.E.; Walker, G.C. Biosynthetic control of molecular weight in the polymerization of the octasaccharide subunits of succinoglycan, a symbiotically important exopolysaccharide of Rhizobium meliloti. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 13477–13482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solanki, R.; Dhanka, M.; Thareja, P.; Bhatia, D. Self-healing, injectable chitosan-based hydrogels: Structure, properties and biological applications. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 5365–5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Fu, R.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J. In vitro and in vivo anti-inflammatory activity of a succinoglycan Riclin from Agrobacterium sp. ZCC3656. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 127, 1716–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jofré, E.; Liaudat, J.P.; Medeot, D.; Becker, A. Monitoring succinoglycan production in single Sinorhizobium meliloti cells by Calcofluor white M2R staining and time-lapse microscopy. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 181, 918–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.F.; Penterman, J.; Shabab, M.; Chen, E.J.; Walker, G.C. Important late-stage symbiotic role of the Sinorhizobium meliloti exopolysaccharide succinoglycan. J. Bacteriol. 2018, 200, e00665-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zevenhuizen, L. Succinoglycan and galactoglucan. Carbohydr. Polym. 1997, 33, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breedveld, M.; Zevenhuizen, L.; Zehnder, A. Osmotically induced oligo-and polysaccharide synthesis by Rhizobium meliloti SU-47. Microbiology 1990, 136, 2511–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Jeong, J.-P.; Park, S.; Park, S.-I.; Jung, S. Enhanced physicochemical, rheological and antioxidant properties of highly succinylated succinoglycan exopolysaccharides obtained through succinic anhydride esterification reaction. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 298, 140007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andhare, P.; Goswami, D.; Delattre, C.; Pierre, G.; Michaud, P.; Pathak, H. Edifying the strategy for the finest extraction of succinoglycan from Rhizobium radiobacter strain CAS. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2017, 60, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jung, S. Biocompatible and self-recoverable succinoglycan dialdehyde-crosslinked alginate hydrogels for pH-controlled drug delivery. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 250, 116934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knirel, Y.A.; Naumenko, O.I.; Sof’ya, N.S.; Perepelov, A.V. Chemical methods for selective cleavage of glycosidic bonds in the structural analysis of bacterial polysaccharides. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2019, 88, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertram-Drogatz, P.; Quester, I.; Becker, A.; Pühler, A. The Sinorhizobium meliloti MucR protein, which is essential for the production of high-molecular-weight succinoglycan exopolysaccharide, binds to short DNA regions upstream of exoH and exoY. Mol. General Genet. MGG 1998, 257, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, T.; Yoshimuka, T.; Hidaka, H.; Koreeda, A. Production of a new acidic polysaccharide, succinoglucan by Alcaligenes faecalis var. myxogenes. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1965, 29, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Park, S.; Kim, J.; Jeong, J.-p.; Jung, S. Rheological, antibacterial, antioxidant properties of D-mannitol-induced highly viscous succinoglycans produced by Sinorhizobium meliloti Rm 1021. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 147, 109346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, Y.; Jeong, J.-p.; Kim, J.-M.; Kim, M.S.; Jung, S. A pH-sensitive drug delivery using biodegradable succinoglycan/chitosan hydrogels with synergistic antibacterial activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 242, 124888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, F.; Alves, V.D.; Pais, J.; Costa, N.; Oliveira, C.; Mafra, L.; Hilliou, L.; Oliveira, R.; Reis, M.A. Characterization of an extracellular polysaccharide produced by a Pseudomonas strain grown on glycerol. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhold, B.B.; Chan, S.Y.; Reuber, T.L.; Marra, A.; Walker, G.C.; Reinhold, V.N. Detailed structural characterization of succinoglycan, the major exopolysaccharide of Rhizobium meliloti Rm1021. J. Bacteriol. 1994, 176, 1997–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouly, C.; Colquhoun, I.J.; Jodelet, A.; York, G.; Walker, G.C. NMR studies of succinoglycan repeating-unit octasaccharides from Rhizobium meliloti and Agrobacterium radiobacter. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 1995, 17, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matulová, M.; Toffanin, R.; Navarini, L.; Gilli, R.; Paoletti, S.; Cesàro, A. NMR analysis of succinoglycans from different microbial sources: Partial assignment of their 1H and 13C NMR spectra and location of the succinate and the acetate groups. Carbohydr. Res. 1994, 265, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Kim, S.; Jung, S. Fabrication and characterization of polysaccharide metallohydrogel obtained from succinoglycan and trivalent chromium. Polymers 2021, 13, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gravanis, G.; Milas, M.; Rinaudo, M.; Clarke-Sturman, A.J. Rheological behaviour of a succinoglycan polysaccharide in dilute and semi-dilute solutions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 1990, 12, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneda, I.; Onodera, Y. Consistency change of succinoglycan aqueous sodium chloride solution during cooling process. Nihon Reoroji Gakkaishi 2009, 37, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Moosavi-Nasab, M.; Taherian, A.R.; Bakhtiyari, M.; Farahnaky, A.; Askari, H. Structural and rheological properties of succinoglycan biogums made from low-quality date syrup or sucrose using agrobacterium radiobacter inoculation. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2012, 5, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Li, P.; Lei, F.; Yao, X.; Wang, K. Tunable and self-healing properties of polysaccharide-based hydrogels through polymer architecture modulation. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 14053–14063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Qiu, Z.; Gong, H.; Zhu, C.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Dong, M. Rheological behaviors of microbial polysaccharides with different substituents in aqueous solutions: Effects of concentration, temperature, inorganic salt and surfactant. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 219, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Zheng, X. Effective modified xanthan gum fluid loss agent for high-temperature water-based drilling fluid and the filtration control mechanism. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 23788–23801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Sun, H.; Shi, X.; Xu, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z. Fundamental investigation of the effects of modified starch, carboxymethylcellulose sodium, and xanthan gum on hydrate formation under different driving forces. Energies 2019, 12, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaudi, L.V.; Giordano, W. An integrated view of biofilm formation in rhizobia. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2010, 304, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaudo, M. Chitin and chitosan: Properties and applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2006, 31, 603–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnieri, A.; Triunfo, M.; Scieuzo, C.; Ianniciello, D.; Tafi, E.; Hahn, T.; Zibek, S.; Salvia, R.; De Bonis, A.; Falabella, P. Antimicrobial properties of chitosan from different developmental stages of the bioconverter insect Hermetia illucens. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Sun, X.; Wang, L.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, J.; Xu, X. In vitro and in vivo anti-Listeria effect of Succinoglycan Riclin through regulating MAPK/IL-6 axis and metabolic profiling. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 150, 802–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nocelli, N.; Bogino, P.C.; Banchio, E.; Giordano, W. Roles of extracellular polysaccharides and biofilm formation in heavy metal resistance of rhizobia. Materials 2016, 9, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, H.; Aulova, A.; Ghai, V.; Pandit, S.; Lovmar, M.; Mijakovic, I.; Kádár, R. Polysaccharide-based antibacterial coating technologies. Acta Biomater. 2023, 168, 42–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Lin, Z.; Cortez-Jugo, C.; Qiao, G.G.; Caruso, F. Antimicrobial phenolic materials: From assembly to function. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202423654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haktaniyan, M.; Bradley, M. Polymers showing intrinsic antimicrobial activity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 8584–8611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, R.; Zhang, L.; Ou, R.; Xu, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhan, X.-Y.; Li, D. Polysaccharide-based hydrogels for wound dressing: Design considerations and clinical applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 845735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, D.; Yu, Y.; Zheng, Y. Insights into the role of natural polysaccharide-based hydrogel wound dressings in biomedical applications. Gels 2022, 8, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Li, L. Structural characterization and antioxidant activity of polysaccharide from four auriculariales. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 229, 115407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Kong, F.; Li, N.; Zhang, D.; Yan, C.; Lv, H. Purification, structural characterization and in vitro antioxidant activity of a novel polysaccharide from Boshuzhi. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 147, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Jiang, T.; Xu, J.; Xi, W.; Shang, E.; Xiao, P.; Duan, J.-A. The relationship between polysaccharide structure and its antioxidant activity needs to be systematically elucidated. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 270, 132391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safarzadeh Kozani, P.; Safarzadeh Kozani, P.; Hamidi, M.; Valentine Okoro, O.; Eskandani, M.; Jaymand, M. Polysaccharide-based hydrogels: Properties, advantages, challenges, and optimization methods for applications in regenerative medicine. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2022, 71, 1319–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniyam, T.; Ahn, H.-B.; Lim, J.; Basu, A.; Kubiak, J.Z.; Rampogu, S.; Nathan, V.K. Therapeutic potential of polysaccharides in inflammation: Current insights and future directions. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 166, 115538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Kong, C.; Cheng, S.; Xu, X.; Zhang, J. Succinoglycan riclin relieves UVB-induced skin injury with anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 235, 123717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Cheng, R.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ge, W.; Sun, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J. The succinoglycan riclin restores beta cell function through the regulation of macrophages on Th1 and Th2 differentiation in type 1 diabetic mice. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 11611–11624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.R.; Muzzarelli, R.A.; Muzzarelli, C.; Sashiwa, H.; Domb, A. Chitosan chemistry and pharmaceutical perspectives. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 6017–6084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jeong, D.; Lee, H.; Kim, D.; Jung, S. Succinoglycan dialdehyde-reinforced gelatin hydrogels with toughness and thermal stability. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 149, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.; Edgar, K.J. Polysaccharide aldehydes and ketones: Synthesis and reactivity. Biomacromolecules 2024, 25, 2261–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nypelö, T.; Berke, B.; Spirk, S.; Sirviö, J.A. Periodate oxidation of wood polysaccharides—Modulation of hierarchies. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 252, 117105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, K.; Jeong, J.-p.; Jung, S. Drug delivery using reduction-responsive hydrogel based on carboxyethyl-succinoglycan with highly improved rheological, antibacterial, and antioxidant properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 335, 122076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.-p.; Kim, K.; Yoon, I.; Jang, S.; Jung, S. Multifunctional biodegradable films of caffeic acid–grafted succinoglycan and polyvinyl alcohol with enhanced antioxidant, antibacterial, and UV-shielding properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 321, 146327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhao, Y.; Ge, W.; Ding, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Xu, X.; Zhang, J. Anti-tumor activity and immunogenicity of a succinoglycan riclin. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 255, 117370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zhuo, Y.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y. Characterization of gelatin-oxidized riclin cryogels and their applications as reusable ice cubes in shrimp preservation. Food Res. Int. 2024, 192, 114766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Zeng, D.; Xia, Y.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, N.; Liu, X.; Sun, X.; Zhao, S. Antibacterial and rapidly absorbable hemostatic sponge by aldehyde modification of natural polysaccharide. Commun. Mater. 2024, 5, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, D.; Jeong, D.; Cho, E.; Jung, S. Colorimetric detection of some highly hydrophobic flavonoids using polydiacetylene liposomes containing pentacosa-10, 12-diynoyl succinoglycan monomers. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Pei, B.; Wang, Z.; Hu, Q. Construction of ordered structure in polysaccharide hydrogel: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 205, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazón, P.; Velazquez, G.; Ramírez, J.A.; Vázquez, M. Polysaccharide-based films and coatings for food packaging: A review. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 68, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.-p.; Yoon, I.; Kim, K.; Jung, S. Structural and Physiochemical Properties of Polyvinyl Alcohol–Succinoglycan Biodegradable Films. Polymers 2024, 16, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, N.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Liu, J.; Gao, Q.; Sun, X. Exopolysaccharide riclin and anthocyanin-based composite colorimetric indicator film for food freshness monitoring. Carbohydrate Polymers 2023, 314, 120882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Jeong, D.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S.; Jung, S. Preparation of succinoglycan hydrogel coordinated with Fe3+ ions for controlled drug delivery. Polymers 2020, 12, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Kim, D.; Hu, Y.; Kim, Y.; Hong, I.K.; Kim, M.S.; Jung, S. pH-responsive succinoglycan-carboxymethyl cellulose hydrogels with highly improved mechanical strength for controlled drug delivery systems. Polymers 2021, 13, 3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Shin, Y.; Park, S.; Jeong, J.-p.; Kim, Y.; Jung, S. Multifunctional oxidized succinoglycan/poly (N-isopropylacrylamide-co-acrylamide) hydrogels for drug delivery. Polymers 2022, 15, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Hu, Y.; Jeong, J.-p.; Jung, S. Injectable, self-healable and adhesive hydrogels using oxidized Succinoglycan/chitosan for pH-responsive drug delivery. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 284, 119195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Hu, Y.; Park, S.; Jung, S. Novel succinoglycan dialdehyde/aminoethylcarbamoyl-β-cyclodextrin hydrogels for pH-responsive delivery of hydrophobic drugs. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 305, 120568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.-p.; Kim, K.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y.; Jung, S. New polyvinyl alcohol/succinoglycan-based hydrogels for pH-responsive drug delivery. Polymers 2023, 15, 3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, C.; Chen, S.; Ge, W.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J. Riclin-capped silver nanoparticles as an antibacterial and anti-inflammatory wound dressing. Int. J. Nanomed. 2022, 17, 2629–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Shen, S.; Wu, B.; Peng, D.; Yin, J.; Wang, Y. A Succinoglycan-Riclin-Zinc-Phthalocyanine-Based Composite Hydrogel with Enhanced Photosensitive and Antibacterial Activity Targeting Biofilms. Gels 2025, 11, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, A.R.; Torres, C.A.; Freitas, F.; Reis, M.A.; Alves, V.D.; Coelhoso, I.M. Biodegradable films produced from the bacterial polysaccharide FucoPol. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 71, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.R.; Torres, C.A.; Freitas, F.; Sevrin, C.; Grandfils, C.; Reis, M.A.; Alves, V.D.; Coelhoso, I.M. Development and characterization of bilayer films of FucoPol and chitosan. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 147, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.R.V.; Bandarra, N.M.; Moldão-Martins, M.; Coelhoso, I.M.; Alves, V.D. FucoPol and chitosan bilayer films for walnut kernels and oil preservation. LWT 2018, 91, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumon, M.M.H.; Akib, A.A.; Sarkar, S.D.; Khan, M.A.R.; Uddin, M.M.; Nasrin, D.; Roy, C.K. Polysaccharide-based hydrogels for advanced biomedical engineering applications. ACS Polym. Au 2024, 4, 463–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berradi, A.; Aziz, F.; Achaby, M.E.; Ouazzani, N.; Mandi, L. A comprehensive review of polysaccharide-based hydrogels as promising biomaterials. Polymers 2023, 15, 2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shen, Z.; Wang, H.; Song, Z.; Yu, D.; Li, G.; Liu, X.; Liu, W. Progress in research on metal ion crosslinking alginate-based gels. Gels 2024, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz Atay, H. Antibacterial activity of chitosan-based systems. In Functional Chitosan: Drug Delivery and Biomedical Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 457–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trucco, D.; Riacci, L.; Vannozzi, L.; Manferdini, C.; Arrico, L.; Gabusi, E.; Lisignoli, G.; Ricotti, L. Primers for the Adhesion of Gellan Gum-Based Hydrogels to the Cartilage: A Comparative Study. Macromol. Biosci. 2022, 22, 2200096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Kim, Y.; Jeong, J.-p.; Park, S.; Shin, Y.; Hong, I.K.; Kim, M.S.; Jung, S. Novel temperature/pH-responsive hydrogels based on succinoglycan/poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) with improved mechanical and swelling properties. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 174, 111308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.J. Amine coupling through EDC/NHS: A practical approach. In Surface Plasmon Resonance: Methods and Protocols; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardine, A. Amino-functionalized polysaccharide derivatives: Synthesis, properties and application. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 5, 100309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Hong, S.; Zhao, H.; Vuong, T.V.; Master, E.R. Biocatalytic cascade to polysaccharide amination. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2024, 17, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, G.; Punta, C.; Delattre, C.; Melone, L.; Dubessay, P.; Fiorati, A.; Pastori, N.; Galante, Y.M.; Michaud, P. TEMPO-mediated oxidation of polysaccharides: An ongoing story. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 165, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, T.; Isogai, A. TEMPO-mediated oxidation of native cellulose. The effect of oxidation conditions on chemical and crystal structures of the water-insoluble fractions. Biomacromolecules 2004, 5, 1983–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, N.; Wada, M.; Isogai, A. TEMPO-mediated oxidation of (1→3)-β-d-glucans. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 77, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, N.; Hirota, M.; Saito, T.; Isogai, A. Oxidation of curdlan and other polysaccharides by 4-acetamide-TEMPO/NaClO/NaClO2 under acid conditions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 81, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, R.; Saito, T.; Isogai, A. Cellulose nanofibrils prepared from softwood cellulose by TEMPO/NaClO/NaClO2 systems in water at pH 4.8 or 6.8. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2012, 51, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dace, R.; McBride, E.; Brooks, K.; Gander, J.; Buszko, M.; Doctor, V. Comparison of the anticoagulant action of sulfated and phosphorylated polysaccharides. Thromb. Res. 1997, 87, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, T.; Wagenknecht, W. Anticoagulant potential of regioselective derivatized cellulose. Biomaterials 2001, 22, 2719–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Chi, Y.; Hwang, H.; Wang, P. Directional preparation of anticoagulant-active sulfated polysaccharides from Enteromorpha prolifera using artificial neural networks. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ni, G.; Xu, J.; Tian, Y.; Liu, X.; Gao, J.; Gao, Q.; Shen, Y.; Yan, Z. Sulfated modification, basic characterization, antioxidant and anticoagulant potentials of polysaccharide from Sagittaria trifolia. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 104812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Meng, C.-g.; Yan, Y.-h.; Shan, Y.-n.; Kan, J.; Jin, C.-h. Structure, physical property and antioxidant activity of catechin grafted Tremella fuciformis polysaccharide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 82, 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spizzirri, U.G.; Parisi, O.I.; Iemma, F.; Cirillo, G.; Puoci, F.; Curcio, M.; Picci, N. Antioxidant–polysaccharide conjugates for food application by eco-friendly grafting procedure. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 79, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Du, D.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, C.; Hua, Z.; Chen, J.; Shi, D. Injectable dopamine–polysaccharide in situ composite hydrogels with enhanced adhesiveness. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 9, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah; Cai, J.; Hafeez, M.A.; Wang, Q.; Farooq, S.; Huang, Q.; Tian, W.; Xiao, J. Biopolymer-based functional films for packaging applications: A review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1000116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fradinho, J.; Allegue, L.; Ventura, M.; Melero, J.; Reis, M.; Puyol, D. Up-scale challenges on biopolymer production from waste streams by Purple Phototrophic Bacteria mixed cultures: A critical review. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 327, 124820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lestido-Cardama, A.; Barbosa-Pereira, L.; Sendón, R.; Bustos, J.; Losada, P.P.; de Quirós, A.R.B. Chemical safety and risk assessment of bio-based and/or biodegradable polymers for food contact: A review. Food Res. Int. 2025, 202, 115737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavez, B.A.; Raghavan, V.; Tartakovsky, B. A comparative analysis of biopolymer production by microbial and bioelectrochemical technologies. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 16105–16118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Strain | Media | EPS Production Media Component | Culture Condition | Yield | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021 | GMS medium | Mannitol (C source) L-glutamic acid (N source) Potassium phosphate dibasic Potassium phosphate monobasic Magnesium sulfate Calcium chloride Trace element | 168 h, 30 °C, 7.0 pH, 200 rpm | 7.8 g/L | [97] |

| Sinorhizobium meliloti Rm 2011 | GMS medium | Mannitol (C source) L-glutamic acid (N source) Potassium phosphate dibasic Potassium phosphate monobasic Magnesium sulfate Calcium chloride Trace element | 240 h, 30 °C, 200 rpm | 0.81 g/L | [96,114] |

| Rhizobium radiobacter ATCC 19358 | Sugar-yeast extract Medium | Sucrose (C source) Yeast extract (N source) CaCO3 | 72 h, 30 °C, 7.2 pH, 500–1000 rpm, DO 40~60% | 14 g/L | [102] |

| Rhizobium radiobacter strain CAS | Bushnell Hass broth | Sucrose (C source) Ammonium Nitrate (N source) Potassium phosphate dibasic Potassium phosphate monobasic Magnesium sulfate Calcium chloride Ferric chloride | 96 h, 30 °C, 7.0 pH, 150 rpm | 3.01 g/L | [111,115] |

| Agrobacterium sp. ZCC3656 | M9 medium | Sucrose (C source) Ammonium nitrate (N source) Potassium phosphate dibasic Potassium phosphate monobasic Magnesium sulfate Calcium chloride Ferric chloride | 72 h, 30 °C, 7.2 pH, 250 rpm | 21.1 g/L | [105] |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | GMS medium | Sucrose (C source) Lysine (N source) Potassium phosphate dibasic Potassium phosphate monobasic Magnesium sulfate Calcium chloride Ferric chloride | 96 h, 30 °C, 7.0 pH, 150, 500–1100 rpm, DO 40~60% | 13.7 g/L | [58] |

| Pseudomonas oleovorans NRRL B-14682 | Medium E* | Glycerol (C source) Ammonium dihydrogen phosphate (N source) Potassium phosphate dibasic Potassium phosphate monobasic Magnesium sulfate Microelement | 96 h, 30 °C, 6.75–6.85 pH 200, 400–800 rpm DO 10% | 8.11 g/L | [118] |

| Derivatives | Structure | Reaction Mechanism | Structure Analysis | Main Properties | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkalian succinoglycan riclin |  | NaOH condition | FTIR, NMR, XPS | Antioxidant activity, Anti-inflammatory activity, Anti-tumor activity, biocompatibility | [133,153] |

| Aldehyde-modified riclin (AR) |  | NaOH condition, Periodate oxidation | FTIR, XPS, XRD | Antibacterial activity, antioxidant activity, biocompatibility, blood coagulation, gelation, tissue adhesiveness | [154,155] |

| Succinoglycan dialdehyde |  | Periodate oxidation | FTIR, NMR, XRD | Adhesiveness, biodegradability, biocompatibility, imine bond based gelation, thermal stability | [112,148] |

| Carboxyethyl succinoglycan |  | 3-Chloropropionic acid SN2 reaction with 0.25M NaOH | FTIR, NMR | Antioxidant activity, antibacterial activity, biocompatibility, increased rheological property, thermal stability | [151] |

| Highly succinylated succinoglycan |  | Succinic anhydride esterification with DMAP | FTIR, NMR, XRD | Antioxidant activity, biocompatibility, increased rheological property, thermal stability | [110] |

| Caffeic acid succinoglycan |  | EDC/DMAP method with caffeic acid | FTIR, NMR | Antibacterial activity, antioxidant activity biocompatibility, biodegradability, hydrophobicity, UV blocking property | [152] |

| Pentacosa-10,12-diynoyl Succinoglycan |  | Reductive amination with DMSO | NMR, MALDI-TOF | Colorimetric detection | [156] |

| Polymer | Component | Reaction Mechanism | Structure Analysis | Main Properties | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Film | SG, Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) | Hydrogen bonding, casting method | FTIR, SEM, DSC | Biodegradability, tensile strength, film-forming property | [159] |

| Caffeic acid modified SG, Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) | Phenol grafting, casting method | FTIR, NMR, SEM | Antibacterial activity, antioxidant activity, biodegradability, tensile strength, UV blocking | [152] | |

| Riclin, Anthocyanin | Hydrogen bonding & physical blending | FTIR, SEM, UV-vis | pH-sensitive colorimetric indicator, food freshness monitoring | [160] | |

| Hydrogel | Agarose, SG | Physical blending & pH-responsive gelation | FTIR, SEM, Rheology | pH-responsiveness, sustained drug release, biocompatibility, hydrogel flexibility, stimuli-responsive controlled drug releasing | [37] |

| SG, Cr3+ ions | Ionic crosslinking via trivalent chromium coordination | FTIR, XRD, Rheology | High mechanical strength, thermal stability, metal ion coordination, controlled swelling | [122] | |

| SG, Fe3+ ions | Ionic coordination between SG carboxyl groups and Fe3+ | FTIR, SEM, Rheology, UV-vis | Sustained release kinetics, pH-responsive swelling, biocompatibility | [161] | |

| Hydrogel | SG, Carboxymethyl Cellulose | Electrostatic interaction & hydrogen bonding network | FTIR, XRD, Rheology, SEM | Enhanced mechanical strength, pH-responsiveness, improved swelling behavior, controlled drug releasing | [162] |

| SG, Chitosan | Electrostatic interaction & ionic crosslinking (NH3+ of chitosan with COO− of SG) | FTIR, SEM, Rheology | Synergistic antibacterial activity, pH-responsive drug release, biocompatibility | [117] | |

| SGDA, Gelatin | Schiff base crosslinking (aldehyde–amine) | FTIR, NMR, XRD, Rheology | High toughness, improved thermal stability, biocompatibility, controlled drug releasing | [148] | |

| SGDA, Alginate | Imine bond (aldehyde–hydrazine interaction) | FTIR, SEM, Rheology | Self-healing, pH-controlled release, biocompatibility | [112] | |

| SGDA/Poly(NIPAAm-co-AAm) | Radical polymerization, Schiff base crosslinking | FTIR, SEM, Rheology, DSC | Thermo-responsive behavior, multifunctional drug release, biocompatibility | [163] | |

| SGDA, Chitosan | Schiff base dynamic covalent bonding | FTIR, Rheology, SEM | Self-healing, adhesiveness, injectability, pH-responsive | [164] | |

| SGDA, Amino-β-cyclodextrin | Schiff base bonding (aldehyde–amine) | FTIR, NMR, SEM | Encapsulation of hydrophobic drugs, pH-responsiveness, sustained release | [165] | |

| Hydrogel | SG, Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) | Hydrogen bonding & physical blending | FTIR, SEM, XRD | pH-responsive swelling, sustained drug release, biocompatibility | [166] |

| Carboxyethyl-SG (CE-SG), Fe3+ ion | metal–carboxylate coordination crosslinking between Fe3+ and –COO− groups of CE-SG | FTIR, NMR, Rheology, SEM | Improved antibacterial & antioxidant activity, reduction-responsive swelling, enhanced rheology | [151] | |

| Gelatin, Oxidized Riclin | Schiff base crosslinking | FTIR, SEM, Rheology | Reusable cryogels, thermal stability, shrimp preservation | [154] | |

| Riclin, Ag nanoparticles | Riclin reduction & capping of Ag+ | FTIR, UV-vis, TEM | Antibacterial activity, anti-inflammatory wound healing, sustained releasing | [167] | |

| Riclin, Zn-Phthalocyanine | Photodynamic composite formation | FTIR, UV-vis, Rheology | Photodynamic antibacterial activity, biofilm inhibition, photodynamic wound therapy | [168] | |

| Riclin/PEGDGE | Epoxy crosslinking with hydroxyl groups of riclin | FTIR, SEM, Rheology | Soft filler, biocompatibility, tissue engineering application | [38] | |

| Aldehyde-modified riclin | Periodate oxidation, Schiff base crosslinking | FTIR, SEM | Hemostatic sponge, antibacterial activity, fast absorbability | [155] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, K.; Jeong, J.-p.; Jung, S. Advances in Succinoglycan-Based Biomaterials: Structural Features, Functional Derivatives, and Multifunctional Applications. Polysaccharides 2025, 6, 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040106

Kim K, Jeong J-p, Jung S. Advances in Succinoglycan-Based Biomaterials: Structural Features, Functional Derivatives, and Multifunctional Applications. Polysaccharides. 2025; 6(4):106. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040106

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Kyungho, Jae-pil Jeong, and Seunho Jung. 2025. "Advances in Succinoglycan-Based Biomaterials: Structural Features, Functional Derivatives, and Multifunctional Applications" Polysaccharides 6, no. 4: 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040106

APA StyleKim, K., Jeong, J.-p., & Jung, S. (2025). Advances in Succinoglycan-Based Biomaterials: Structural Features, Functional Derivatives, and Multifunctional Applications. Polysaccharides, 6(4), 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040106