Polysaccharide-Based Drug Delivery Systems in Pediatrics: Addressing Age-Specific Challenges and Therapeutic Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

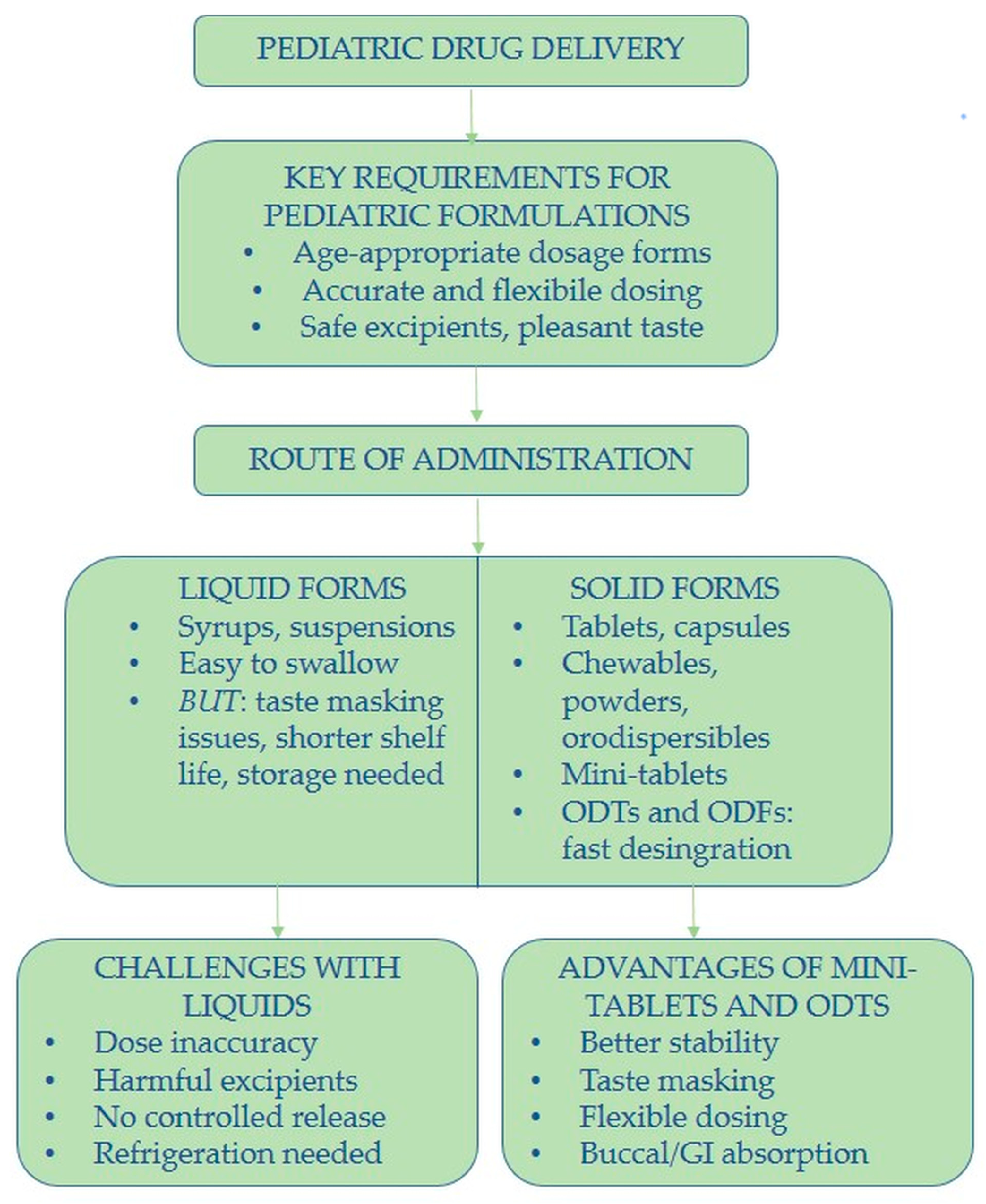

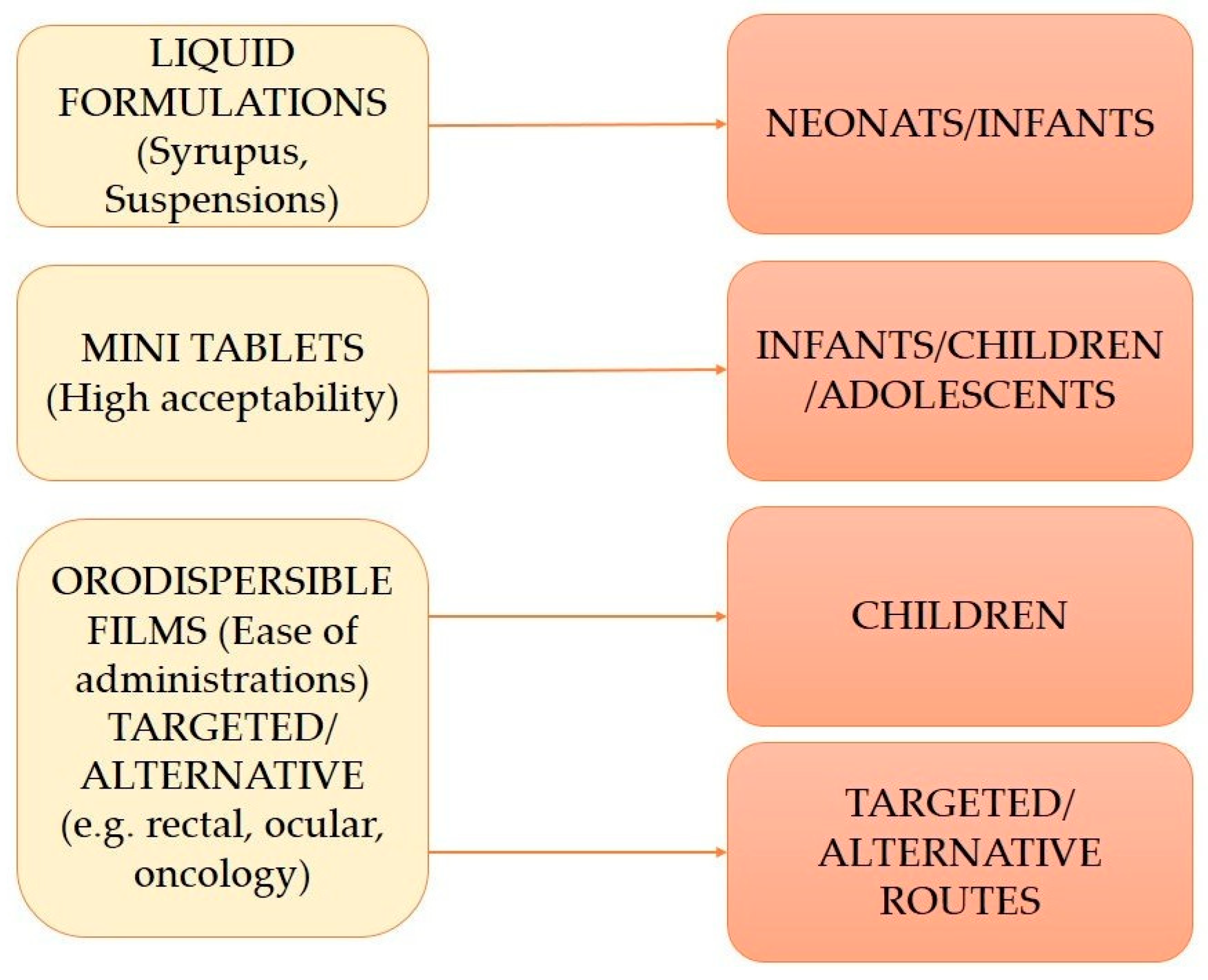

2. Formulation Trends and Acceptability in Pediatric Drug Delivery

3. Pediatric Drug Delivery: Age-Specific Considerations

3.1. Physiological and Pharmacological Differences Across Pediatric Age Groups

3.2. Impact on Drug ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion)

4. Polysaccharide Polymers: Characteristics and Uses in Pediatric Drug Delivery

4.1. Chitosan

4.2. Hyaluronic Acid

4.3. Alginate

4.4. Pectin

4.5. Dextran

4.6. Guar Gum

4.7. Cellulose Derivates

4.8. Inulin

4.9. Other Polysaccharides Explored in Pediatric Drug Delivery

5. Advantages of Polysaccharide Polymers in Drug Delivery

5.1. Biocompatibility and Biodegradability

5.2. Chemical Modification Potential

5.3. Mucoadhesion Properties

5.4. Biological Activities

5.5. Safety Profile

6. Formulation Strategies for Polysaccharide-Based Delivery Systems

6.1. Polysaccharide–Drug Conjugates

6.2. Polysaccharide Particles

6.3. Hydrogels

6.4. Coatings and Films

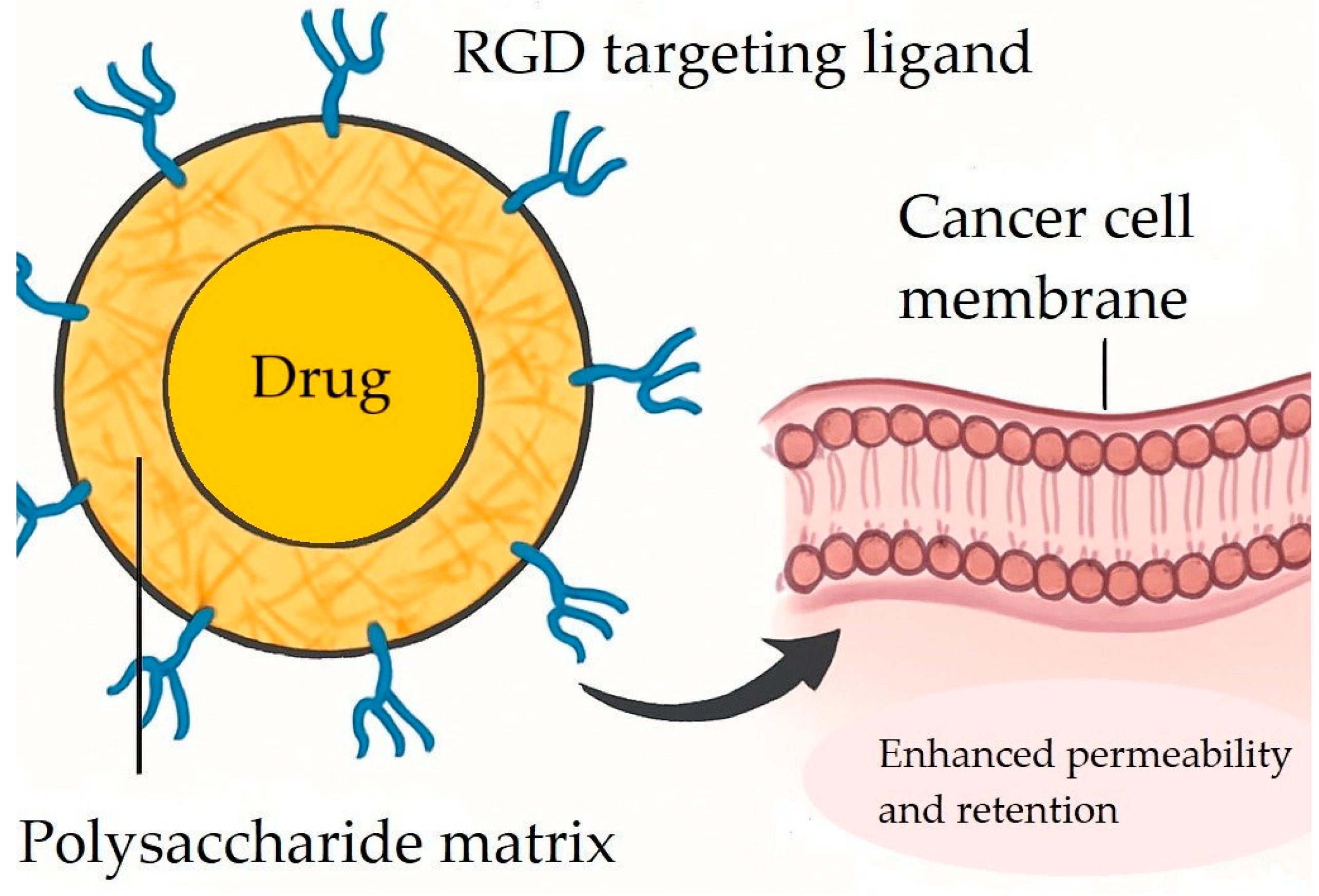

7. Overcoming Delivery Challenges: Polysaccharide Polymers in Pediatric Cancer Treatment

7.1. Limitations of Conventional Chemotherapy

Biological Barriers to Drug Delivery

7.2. Improving Cancer Treatment Outcomes with Polysaccharide Drug Carriers

7.3. Colon-Specific Drug Delivery Using Polysaccharides

7.4. Alginate-Coated Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles: A Safer Delivery System for Neuroblastoma Therapy

7.5. Active Tumor Targeting with RGD Peptides

7.6. Theranostic Applications of Polysaccharide Biopolymers in Modern Cancer Treatment

7.7. Addressing the Gap in Polysaccharide-Based Delivery Systems for Pediatric Oncology

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ODTs | Mini orodispersible tablets |

| ODFs | Orodispersible films |

| CYP | Cytochrome P450 |

| HPMC | Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose |

| MC | Methylcellulose |

| EC | Ethylcellulose |

| HEC | Hydroxyethyl cellulose |

| PVA | Polyvinyl alcohol |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| HA | Hyaluronic acid |

| HM | High Methoxyl |

| LM | Low Methoxyl |

| GRAS | Generally recognized as safe |

References

- van den Anker, J.; Reed, M.D.; Allegaert, K.; Kearns, G.L. Developmental changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 58, S10–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Rosenbaum, S. Developmental pharmacokinetics in pediatric populations. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 19, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batchelor, H.K.; Marriott, J.F. Paediatric pharmacokinetics: Key considerations. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 79, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchelor, H.K.; Marriott, J.F. Formulations for children: Problems and solutions. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 79, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerrard, S.E.; Walsh, J.; Bowers, N.; Salunke, S.; Hershenson, S. Innovations in pediatric drug formulations and administration technologies for low resource settings. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, D.; Kirby, D.; Bryson, S.; Shah, M.; Mohammed, A.R. Paediatric specific dosage forms: Patient and formulation considerations. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 616, 121501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Shen, L. Medication adherence and pharmaceutical design strategies for pediatric patients: An overview. Drug Discov. Today 2023, 28, 103766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, S.; Burgess, A. How to identify and manage ‘problem’excipients in medicines for children. Pharm. J. 2017, 299, 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, G.A.; Vallejo, E. Primary packaging considerations in developing medicines for children: Oral liquid and powder for constitution. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 104, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Rachidi, S.; Larochelle, J.M.; Morgan, J.A. Pharmacists and pediatric medication adherence: Bridging the gap. Hosp. Pharm. 2017, 52, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracken, L.; McDonough, E.; Ashleigh, S.; Wilson, F.; Shakeshaft, J.; Ohia, U.; Mistry, P.; Jones, H.; Kanji, N.; Liu, F. Can children swallow tablets? Outcome data from a feasibility study to assess the acceptability of different-sized placebo tablets in children (creating acceptable tablets (CAT)). BMJ Open 2020, 10, e036508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klingmann, V. Acceptability of mini-tablets in young children: Results from three prospective cross-over studies. AAPS PharmSciTech 2017, 18, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Riet-Nales, D.A.; de Neef, B.J.; Schobben, A.F.; Ferreira, J.A.; Egberts, T.C.; Rademaker, C.M. Acceptability of different oral formulations in infants and preschool children. ADC 2013, 98, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, T.G.; Day, C.M.; Petrovsky, N.; Garg, S. Review of polysaccharide particle-based functional drug delivery. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 221, 94–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benalaya, I.; Alves, G.; Lopes, J.; Silva, L.R. A review of natural polysaccharides: Sources, characteristics, properties, food, and pharmaceutical applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; He, Z.; Liang, Y.; Peng, T.; Hu, Z. Insights into algal polysaccharides: A review of their structure, depolymerases, and metabolic pathways. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 1749–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasher, P.; Sharma, M.; Mehta, M.; Satija, S.; Aljabali, A.A.; Tambuwala, M.M.; Anand, K.; Sharma, N.; Dureja, H.; Jha, N.K. Current-status and applications of polysaccharides in drug delivery systems. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 42, 100418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.; Rana, D.; Salave, S.; Gupta, R.; Patel, P.; Karunakaran, B.; Sharma, A.; Giri, J.; Benival, D.; Kommineni, N. Chitosan: A potential biopolymer in drug delivery and biomedical applications. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, A.; Khan, S.; Iqbal, D.N.; Shrahili, M.; Haider, S.; Mohammad, K.; Mohammad, A.; Rizwan, M.; Kanwal, Q.; Mustafa, G. Advances in chitosan-based drug delivery systems: A comprehensive review for therapeutic applications. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 210, 112983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liang, H.; Chen, X.; Tan, H.J.P. Natural polymer-based hydrogels: From polymer to biomedical applications. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dash, M.; Chiellini, F.; Ottenbrite, R.M.; Chiellini, E. Chitosan—A versatile semi-synthetic polymer in biomedical applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2011, 36, 981–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhi, R.; Sahoo, S.K.; Das, A. Applications of polysaccharides in topical and transdermal drug delivery: A recent update of literature. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 58, e20802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, S.; Hina, M.; Iqbal, J.; Rajpar, A.; Mujtaba, M.; Alghamdi, N.; Wageh, S.; Ramesh, K.; Ramesh, S.J.P. Fundamental concepts of hydrogels: Synthesis, properties, and their applications. Polymers 2020, 12, 2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollmer, E.; Ungell, A.-L.; Nicolas, J.-M.; Klein, S. Review of paediatric gastrointestinal physiology relevant to the absorption of orally administered medicines. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2022, 181, 114084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillhart, C.; Vučićević, K.; Augustijns, P.; Basit, A.W.; Batchelor, H.; Flanagan, T.R.; Gesquiere, I.; Greupink, R.; Keszthelyi, D.; Koskinen, M. Impact of gastrointestinal physiology on drug absorption in special populations––An UNGAP review. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 147, 105280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, J.M.; Bouzom, F.; Hugues, C.; Ungell, A.L. Oral drug absorption in pediatrics: The intestinal wall, its developmental changes and current tools for predictions. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2017, 38, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omari, T.; Davidson, G. Multipoint measurement of intragastric pH in healthy preterm infants. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003, 88, F517–F520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonner, J.J.; Vajjah, P.; Abduljalil, K.; Jamei, M.; Rostami-Hodjegan, A.; Tucker, G.T.; Johnson, T.N. Does age affect gastric emptying time? A model-based meta-analysis of data from premature neonates through to adults. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2015, 36, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emoto, C.; Johnson, T.N. Cytochrome P450 enzymes in the pediatric population: Connecting knowledge on P450 expression with pediatric pharmacokinetics. Adv. Pharmacol. 2022, 95, 365–391. [Google Scholar]

- Subash, S.; Prasad, B. Age-dependent changes in cytochrome P450 abundance and composition in human liver. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2024, 52, 1363–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfatama, M.; Choukaife, H.; Alkhatib, H.; Al Rahal, O.; Zin, N.Z.M. A comprehensive review of oral chitosan drug delivery systems: Applications for oral insulin delivery. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2024, 13, 20230205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karavasili, C.; Gkaragkounis, A.; Fatouros, D.G. Patent landscape of pediatric-friendly oral dosage forms and administration devices. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2021, 31, 663–685. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Giuliano, E.; Longo, E.; Gagliardi, A.; Costa, S.; Squillace, F.; Voci, S.; Verdiglione, M.; Cosco, D. Development and Characterization of Niaprazine-Loaded Xanthan Gum-Based Gel for Oral Administration. Gels 2025, 11, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şenel, S.; Yüksel, S. Chitosan-based particulate systems for drug and vaccine delivery in the treatment and prevention of neglected tropical diseases. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2020, 10, 1644–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazekas, T.; Eickhoff, P.; Pruckner, N.; Vollnhofer, G.; Fischmeister, G.; Diakos, C.; Rauch, M.; Verdianz, M.; Zoubek, A.; Gadner, H. Lessons learned from a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled study with a iota-carrageenan nasal spray as medical device in children with acute symptoms of common cold. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 12, 147. [Google Scholar]

- Duarah, S.; Sharma, M.; Wen, J. Recent advances in microneedle-based drug delivery: Special emphasis on its use in paediatric population. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2019, 136, 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; Francis, A.P.; Priya, V.V.; Patil, S.; Mustaq, S.; Khan, S.S.; Alzahrani, K.J.; Banjer, H.J.; Mohan, S.K.; Mony, U. Polysaccharide-drug conjugates: A tool for enhanced cancer therapy. Polymers 2022, 14, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pui, C.-H.; Gajjar, A.J.; Kane, J.R.; Qaddoumi, I.A.; Pappo, A.S. Challenging issues in pediatric oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 8, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Santen, H.M.; Chemaitilly, W.; Meacham, L.R.; Tonorezos, E.S.; Mostoufi-Moab, S. Endocrine health in childhood cancer survivors. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 67, 1171–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Song, S.; Wei, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhao, M.; Guo, J.; Zhang, J. Sulfated modification of the polysaccharide from Sphallerocarpus gracilis and its antioxidant activities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 87, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Zhai, Y.; Wang, X.; Fan, Q.; Dong, X.; Chen, M.; Han, T. Phosphorylation of polysaccharides: A review on the synthesis and bioactivities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 184, 946–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Hu, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, X.; Zhao, R.; Gao, M.; Li, Z.; Feng, Y.; Xu, Y. Improvement of antibacterial activity of polysaccharides via chemical modification: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 269, 132163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.S.A.; Naveed, M.; Jost, N. Polysaccharides; classification, chemical properties, and future perspective applications in fields of pharmacology and biological medicine (a review of current applications and upcoming potentialities). J. Polym. Environ. 2021, 29, 2359–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, H.; Chen, K.; Jin, M.; Vu, S.H.; Jung, S.; He, N.; Zheng, Z.; Lee, M.-S. Application of chitosan/alginate nanoparticle in oral drug delivery systems: Prospects and challenges. Drug Deliv. 2022, 29, 1142–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omidian, H.; Mfoafo, K. Exploring the potential of nanotechnology in pediatric healthcare: Advances, challenges, and future directions. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieto González, N.; Obinu, A.; Rassu, G.; Giunchedi, P.; Gavini, E. Polymeric and lipid nanoparticles: Which applications in pediatrics? Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieto González, N.; Cerri, G.; Molpeceres, J.; Cossu, M.; Rassu, G.; Giunchedi, P.; Gavini, E. Surfactant-free chitosan/cellulose acetate phthalate nanoparticles: An attempt to solve the needs of captopril administration in paediatrics. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, J.; Agrawal, A.; Patravale, V.; Pandya, A.; Orubu, S.; Zhao, M.; Andrews, G.P.; Petit-Turcotte, C.; Landry, H.; Croker, A. The current states, challenges, ongoing efforts, and future perspectives of pharmaceutical excipients in pediatric patients in each country and region. Children 2022, 9, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colletti, M.; Di Paolo, V.; Galardi, A.; Maria Milano, G.; Mastronuzzi, A.; Locatelli, F.; Di Giannatale, A. Nano-delivery in pediatric tumors: Looking back, moving forward. Anticancer. Agents Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 1328–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. ICH E11 (R1) Guideline on Clinical Investigation of Medicinal Products in the Pediatric Population; European Medicines Agency: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- EMA. Guideline on Pharmaceutical Development of Medicines for Paediatric Use. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-pharmaceutical-development-medicines-paediatric-use_en.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Salunke, S.; Brandys, B.; Giacoia, G.; Tuleu, C. The STEP (Safety and Toxicity of Excipients for Paediatrics) database: Part 2–the pilot version. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 457, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, V.W.; Wong, I.C. When do children convert from liquid antiretroviral to solid formulations? Pharm. World Sci. 2005, 27, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyers, R.S. The past, present, and future of oral dosage forms for children. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 29, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lura, A.; Luhn, O.; Gonzales, J.S.; Breitkreutz, J. New orodispersible mini-tablets for paediatric use–A comparison of isomalt with a mannitol based co-processed excipient. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 572, 118804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mfoafo, K.A.; Omidian, M.; Bertol, C.D.; Omidi, Y.; Omidian, H. Neonatal and pediatric oral drug delivery: Hopes and hurdles. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 597, 120296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, F.; Clapham, D.; Krysiak, K.; Batchelor, H.; Field, P.; Caivano, G.; Pertile, M.; Nunn, A.; Tuleu, C. Making medicines baby size: The challenges in bridging the formulation gap in neonatal medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Abeele, J.; Rayyan, M.; Hoffman, I.; Van de Vijver, E.; Zhu, W.; Augustijns, P. Gastric fluid composition in a paediatric population: Age-dependent changes relevant for gastrointestinal drug disposition. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 123, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooij, M.G.; de Koning, B.A.; Huijsman, M.L.; de Wildt, S.N. Ontogeny of oral drug absorption processes in children. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2012, 8, 1293–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Dawes, C. Salivary flow rates and salivary film thickness in five-year-old children. J. Dent. Res. 1990, 69, 1150–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L.; Dawes, C. The surface area of the adult human mouth and thickness of the salivary film covering the teeth and oral mucosa. J. Dent. Res. 1987, 66, 1300–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, K.L.; Aleksunes, L.M.; Brandys, B.; Giacoia, G.P.; Knipp, G.; Lukacova, V.; Meibohm, B.; Nigam, S.K.; Rieder, M.; de Wildt, S.N. Human ontogeny of drug transporters: Review and recommendations of the pediatric transporter working group. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 98, 266–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, Y.E.; Calderon-Nieva, D.; Hamadeh, A.; Edginton, A.N. Development and evaluation of an in silico dermal absorption model relevant for children. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis-Hansen, B. Body composition during growth. In vivo measurements and biochemical data correlated to differential anatomical growth. Pediatrics 1971, 47 (Suppl. S2), 264. [Google Scholar]

- Ghersi-Egea, J.-F.; Saudrais, E.; Strazielle, N. Barriers to drug distribution into the perinatal and postnatal brain. Pharm. Res. 2018, 35, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smits, A.; Annaert, P.; Cavallaro, G.; De Cock, P.A.; de Wildt, S.N.; Kindblom, J.M.; Lagler, F.B.; Moreno, C.; Pokorna, P.; Schreuder, M.F. Current knowledge, challenges and innovations in developmental pharmacology: A combined conect4children Expert Group and European Society for Developmental, Perinatal and Paediatric Pharmacology White Paper. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022, 88, 4965–4984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verscheijden, L.; Van Hattem, A.; Pertijs, J.; De Jongh, C.; Verdijk, R.; Smeets, B.; Koenderink, J.; Russel, F.; de Wildt, S. Developmental patterns in human blood–brain barrier and blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier ABC drug transporter expression. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2020, 154, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhan, N.; Dahal, U.P.; Wahlstrom, J. Development and Evaluation of Ontogeny Functions of the Major UDP-Glucuronosyltransferase Enzymes to Underwrite Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling in Pediatric Populations. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2024, 64, 1222–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badée, J.; Fowler, S.; de Wildt, S.N.; Collier, A.C.; Schmidt, S.; Parrott, N. The ontogeny of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase enzymes, recommendations for future profiling studies and application through physiologically based pharmacokinetic modelling. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2019, 58, 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladumor, M.K.; Bhatt, D.K.; Gaedigk, A.; Sharma, S.; Thakur, A.; Pearce, R.E.; Leeder, J.S.; Bolger, M.B.; Singh, S.; Prasad, B. Ontogeny of hepatic sulfotransferases and prediction of age-dependent fractional contribution of sulfation in acetaminophen metabolism. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2019, 47, 818–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, F.; Johnson, T.N.; Hodgkinson, A.B.; Ogungbenro, K.; Rostami-Hodjegan, A. Does “birth” as an event impact maturation trajectory of renal clearance via glomerular filtration? Reexamining data in preterm and full-term neonates by avoiding the creatinine bias. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 61, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobelli, S.; Guignard, J.-P. Maturation of glomerular filtration rate in neonates and infants: An overview. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2021, 36, 1439–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farasati Far, B.; Naimi-Jamal, M.R.; Safaei, M.; Zarei, K.; Moradi, M.; Yazdani Nezhad, H. A review on biomedical application of polysaccharide-based hydrogels with a focus on drug delivery systems. Polymers 2022, 14, 5432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Singh, B. Emerging trends in designing polysaccharide based mucoadhesive network hydrogels as versatile platforms for innovative delivery of therapeutic agents: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 300, 140229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, H.; Guo, C.; Liu, L.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, T.; He, H.; Gou, J.; Pan, B.; Tang, X. Progress and prospects of polysaccharide-based nanocarriers for oral delivery of proteins/peptides. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 312, 120838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dmour, I.; Islam, N. Recent advances on chitosan as an adjuvant for vaccine delivery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 200, 498–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wassel, M.O.; Sherief, D.I. Ion release and enamel remineralizing potential of miswak, propolis and chitosan nano-particles based dental varnishes. Pediatr. Dent. J. 2019, 29, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouhussein, D.; El Nabarawi, M.A.; Shalaby, S.H.; Abd El-Bary, A. Cetylpyridinium chloride chitosan blended mucoadhesive buccal films for treatment of pediatric oral diseases. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 101676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, C.; Jarak, I.; Veiga, F.; Dourado, M.; Figueiras, A. Pediatric drug development: Reviewing challenges and opportunities by tracking innovative therapies. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kievit, F.M.; Stephen, Z.R.; Wang, K.; Dayringer, C.J.; Sham, J.G.; Ellenbogen, R.G.; Silber, J.R.; Zhang, M. Nanoparticle mediated silencing of DNA repair sensitizes pediatric brain tumor cells to γ-irradiation. Mol. Oncol. 2015, 9, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kievit, F.M.; Veiseh, O.; Fang, C.; Bhattarai, N.; Lee, D.; Ellenbogen, R.G.; Zhang, M. Chlorotoxin labeled magnetic nanovectors for targeted gene delivery to glioma. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 4587–4594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukchin, A.; Sanchez-Navarro, M.; Carrera, A.; Resa-Pares, C.; Castillo-Ecija, H.; Balaguer-Lluna, L.; Teixido, M.; Olaciregui, N.G.; Giralt, E.; Carcaboso, A.M. Amphiphilic polymeric nanoparticles modified with a protease-resistant peptide shuttle for the delivery of SN-38 in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 1314–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Alencar Morais Lima, W.; de Souza, J.G.; García-Villén, F.; Loureiro, J.L.; Raffin, F.N.; Fernandes, M.A.; Souto, E.B.; Severino, P.; Barbosa, R.d.M. Next-generation pediatric care: Nanotechnology-based and AI-driven solutions for cardiovascular, respiratory, and gastrointestinal disorders. World J. Pediatr. 2025, 21, 8–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yao, Y.; Fu, H. Novel pediatric suspension of nanoparticulate zafirlukast for the treatment of asthma: Assessment and evaluation in animal model. Micro Nano Lett. 2021, 16, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojmenovski, A.; Gatarić, B.; Vučen, S.; Railić, M.; Krstonošić, V.; Kukobat, R.; Mirjanić, M.; Škrbić, R.; Račić, A. Formulation and Evaluation of Polysaccharide Microparticles for the Controlled Release of Propranolol Hydrochloride. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuah, L.-H.; Loo, H.-L.; Goh, C.F.; Fu, J.-Y.; Ng, S.-F. Chitosan-based drug delivery systems for skin atopic dermatitis: Recent advancements and patent trends. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2023, 13, 1436–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannin, V.; Lemagnen, G.; Gueroult, P.; Larrouture, D.; Tuleu, C. Rectal route in the 21st Century to treat children. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2014, 73, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, T.J.; Hanning, S.M.; Wu, Z. Advances in rectal drug delivery systems. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2018, 23, 942–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckley, C.; Murphy, E.J.; Montgomery, T.R.; Major, I. Hyaluronic acid: A review of the drug delivery capabilities of this naturally occurring polysaccharide. Polymers 2022, 14, 3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Račić, A.; Krajišnik, D. Biopolymers in mucoadhesive eye drops for treatment of dry eye and allergic conditions: Application and perspectives. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.J.; Dempsey, S.G.; Veale, R.W.; Duston-Fursman, C.G.; Rayner, C.A.; Javanapong, C.; Gerneke, D.; Dowling, S.G.; Bosque, B.A.; Karnik, T. Further structural characterization of ovine forestomach matrix and multi-layered extracellular matrix composites for soft tissue repair. J. Biomater. Appl. 2022, 36, 996–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, M.; Vella, P.; Moffa, A.; Oliveto, G.; Sabatino, L.; Grimaldi, V.; Ferrara, P.; Salvinelli, F. Hyaluronic acid and upper airway inflammation in pediatric population: A systematic review. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 85, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cicco, M.; Peroni, D.; Sepich, M.; Tozzi, M.G.; Comberiati, P.; Cutrera, R. Hyaluronic acid for the treatment of airway diseases in children: Little evidence for few indications. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2020, 55, 2156–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhalidi, H.M.; Hosny, K.M.; Rizg, W.Y. Oral gel loaded by fluconazole-sesame oil nanotransfersomes: Development, optimization, and assessment of antifungal activity. Pharmaceutics 2020, 13, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires, P.C.; Damiri, F.; Zare, E.N.; Hasan, A.; Neisiany, R.E.; Veiga, F.; Makvandi, P.; Paiva-Santos, A.C. A review on natural biopolymers in external drug delivery systems for wound healing and atopic dermatitis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 263, 130296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo, B.; Correia, P.; Gonçalves Junior, J.E.; Sant’Anna, B.; Kerob, D. Benefits of topical hyaluronic acid for skin quality and signs of skin aging: From literature review to clinical evidence. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubashynskaya, N.; Poshina, D.; Raik, S.; Urtti, A.; Skorik, Y.A. Polysaccharides in Ocular Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Račić, A.; Dukovski, B.J.; Lovrić, J.; Dobričić, V.; Vučen, S.; Micov, A.; Stepanović-Petrović, R.; Tomić, M.; Pecikoza, U.; Bajac, J. Synergism of polysaccharide polymers in antihistamine eye drops: Influence on physicochemical properties and in vivo efficacy. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 655, 124033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samiraninezhad, N.; Asadi, K.; Rezazadeh, H.; Gholami, A. Using chitosan, hyaluronic acid, alginate, and gelatin-based smart biological hydrogels for drug delivery in oral mucosal lesions: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 252, 126573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abourehab, M.A.; Rajendran, R.R.; Singh, A.; Pramanik, S.; Shrivastav, P.; Ansari, M.J.; Manne, R.; Amaral, L.S.; Deepak, A. Alginate as a promising biopolymer in drug delivery and wound healing: A review of the state-of-the-art. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablaza, T.J.J.; Crisostomo, E.A.; Uy, M.E.V. A Systematic Review on the Efficacy and Safety of Alginate–based Liquid Formulations in Reducing Gastroesophageal Reflux in Neonates and Infants. Acta Medica Philipp. 2024, 58, 55. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico, V.; Arduino, I.; Vacca, M.; Iacobazzi, R.M.; Altamura, D.; Lopalco, A.; Rizzi, R.; Cutrignelli, A.; Laquintana, V.; Massimo, F. Colonic budesonide delivery by multistimuli alginate/Eudragit® FS 30D/inulin-based microspheres as a paediatric formulation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 302, 120422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruk, K.; Winnicka, K. Alginates combined with natural polymers as valuable drug delivery platforms. Mar. Drugs 2022, 21, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkader, H.; Abdel-Aleem, J.A.; Mousa, H.S.; Elgendy, M.O.; Al Fatease, A.; Abou-Taleb, H.A. Captopril polyvinyl alcohol/sodium alginate/gelatin-based oral dispersible films (ODFs) with modified release and advanced oral bioavailability for the treatment of pediatric hypertension. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Nie, S.; Liu, H.; Ding, P.; Pan, W. Study of an alginate/HPMC-based in situ gelling ophthalmic delivery system for gatifloxacin. Int. J. Pharm. 2006, 315, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kedir, W.M.; Deresa, E.M.; Diriba, T.F. Pharmaceutical and drug delivery applications of pectin and its modified nanocomposites. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultana, N. Biological properties and biomedical applications of pectin and pectin-based composites: A review. Molecules 2023, 28, 7974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, D.U.; Garg, R.; Gaur, M.; Pareek, A.; Prajapati, B.G.; Castro, G.R.; Suttiruengwong, S.; Sriamornsak, P. Pectin hydrogels for controlled drug release: Recent developments and future prospects. Saudi Pharm. J. 2024, 32, 102002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GRAS Substances Database. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/generally-recognized-safe-gras/gras-substances-scogs-database (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Rodríguez-Pombo, L.; Gallego-Fernández, C.; Jørgensen, A.K.; Parramon-Teixidó, C.J.; Cañete-Ramirez, C.; Cabañas-Poy, M.J.; Basit, A.W.; Alvarez-Lorenzo, C.; Goyanes, A. 3D printed personalized therapies for pediatric patients affected by adrenal insufficiency. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2024, 21, 1665–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pombo, L.; de Castro-López, M.J.; Sánchez-Pintos, P.; Giraldez-Montero, J.M.; Januskaite, P.; Duran-Piñeiro, G.; Bóveda, M.D.; Alvarez-Lorenzo, C.; Basit, A.W.; Goyanes, A. Paediatric clinical study of 3D printed personalised medicines for rare metabolic disorders. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 657, 124140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovici, A.R.; Pinteala, M.; Simionescu, N. Dextran formulations as effective delivery systems of therapeutic agents. Molecules 2023, 28, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elalmis, Y.B.; Tiryaki, E.; Ikizler, B.K.; Yucel, S. Dextran-based micro-and nanobiomaterials for drug delivery and biomedical applications. In Micro-And Nanoengineered Gum-Based Biomaterials for Drug Delivery and Biomedical Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 303–331. [Google Scholar]

- Junyaprasert, V.B.; Thummarati, P. Innovative design of targeted nanoparticles: Polymer–drug conjugates for enhanced cancer therapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, U.; Sahoo, S.K.; De Tapas, K.; Ghosh, P.C.; Maitra, A.; Ghosh, P. Biodistribution of fluoresceinated dextran using novel nanoparticles evading reticuloendothelial system. Int. J. Pharm. 2000, 202, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha-e-Silva, R.; Canêo, L.F.; Lourenço Filho, D.D.; Jatene, M.B.; Barbero-Marcial, M.; Oliveira, S.A.; Rocha-e-Silva, M. First use of hypertonic saline dextran in children: A study in safety and effectiveness for atrial septal defect surgery. Shock 2003, 20, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholap, A.D.; Said, R.P.; Pawar, R.D.; Ambore, G.S.; Hatvate, N.T. Importance of carbohydrate-drug conjugates in vaccine development: A detailed review. Compr. Anal. Chem. 2023, 103, 191–256. [Google Scholar]

- Bolandparvaz, A.; Vapniarsky, N.; Harriman, R.; Alvarez, K.; Saini, J.; Zang, Z.; Van De Water, J.; Lewis, J.S. Biodistribution and toxicity of epitope-functionalized dextran iron oxide nanoparticles in a pregnant murine model. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2020, 108, 1186–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-López, C.; Contreras-Esquivel, J.C.; Martinez-Avila, G.C.; Rojas, R.; Boone-Villa, D.; Aguilar, C.N.; Ventura-Sobrevilla, J.M. Guar gum as a promising hydrocolloid: Properties and industry overview. In Applied Chemistry and Chemical Engineering; Apple Academic Press: Burlington, ON, Canada, 2017; Volume 5, pp. 183–205. [Google Scholar]

- Naliyadhara, M.V.; Chovatiya, R.B.; Vekariya, S.R.; Undhad, D.D.; Buddhadev, S.S. Innovative Drug Delivery Systems: The Comprehensive Role of Natural Polymers in Fast-Dissolving Tablets. Eng. Proc. 2025, 87, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Thombare, N.; Jha, U.; Mishra, S.; Siddiqui, M. Guar gum as a promising starting material for diverse applications: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 88, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, A.; Shah, P.A.; Shrivastav, P.S. Guar gum: Versatile natural polymer for drug delivery applications. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 112, 722–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjay, L.R.; Ashokbhai, M.K.; Ghatole, S.; Roy, S.; Kashinath, K.P.; Kaity, S. Strategies for beating bitter taste of pharmaceutical formulations towards better therapeutic outcome. RSC Pharm. 2025, 2, 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Kanojia, N.; Jatindernath; Dalabehera, M.; Chandel, P. Plant-Derived Excipients: Applications in Drug Formulation. In Innovative Pharmaceutical Excipients: Natural Sources; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gokhale, N.; Meval, A.; Gupta, D.; Vinchurkar, K.; Suryawanshi, M. Natural Polymers in Oral Drug Delivery. In Innovative Pharmaceutical Excipients: Natural Sources; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 299–320. [Google Scholar]

- Lukova, P.; Katsarov, P.; Pilicheva, B. Application of starch, cellulose, and their derivatives in the development of microparticle drug-delivery systems. Polymers 2023, 15, 3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, T.; Arora, S.; Pahwa, R. Cellulose and its derivatives: Structure, modification, and application in controlled drug delivery. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 11, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawazi, S.M.; Al-Mahmood, S.M.A.; Chatterjee, B.; Hadi, H.A.; Doolaanea, A.A. Carbamazepine Gel Formulation as a Sustained Release Epilepsy Medication for Pediatric Use. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagami, T.; Ito, E.; Kida, R.; Hirose, K.; Noda, T.; Ozeki, T. 3D printing of gummy drug formulations composed of gelatin and an HPMC-based hydrogel for pediatric use. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 594, 120118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abruzzo, A.; Crispini, A.; Prata, C.; Adduci, R.; Nicoletta, F.P.; Dalena, F.; Cerchiara, T.; Luppi, B.; Bigucci, F. Freeze-dried matrices for buccal administration of propranolol in children: Physico-chemical and functional characterization. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 110, 1676–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Sun, X.; Lin, X.; Yi, W.; Jiang, J. An injectable metal nanoparticle containing cellulose derivative-based hydrogels: Evaluation of antibacterial and in vitro-vivo wound healing activity in children with burn injuries. Int. Wound J. 2022, 19, 666–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, T.; Josling, P.; Dubuske, L. Protective Role of Intranasal Methylcellulose Powder Against Nasal Inflammatory Episodes in Children Attending Daycare Facilities. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2024, 153, AB232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, H.; Liu, N.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, A.; Bo, X. Taste-masking mechanism of brivaracetam oral solution using cyclodextrin and sodium carboxymethyl cellulose. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 675, 125368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotova, E.; Vyazmenov, E.; Bogomilsky, M. New ways of solving the problem of restenosis in the surgical treatment of congenital choanal atresia in children. Vestn. Otorinolaringol. 2020, 85, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winfield, R.D.; Ang, D.N.; Chen, M.K.; Kays, D.W.; Langham, M.R., Jr.; Beierle, E.A. The use of Seprafilm® in pediatric surgical patients. Am. Surg. 2007, 73, 792–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, I.; Ghowsi, M.; Mohammed, L.J.; Haidari, Z.; Nazari, K.; Schiöth, H. Inulin as a Biopolymer; Chemical Structure, Anticancer Effects, Nutraceutical Potential and Industrial Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Polymers 2025, 17, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veereman, G. Pediatric applications of inulin and oligofructose. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 2585S–2589S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okafor, N.I.; Nnaji, N.J. Liposomes, facilitating the encapsulation and improved solubility of zidovudine antiretroviral drug. BioNanoScience 2024, 14, 4877–4894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piriyaprasarth, S.; Sriamornsak, P. Flocculating and suspending properties of commercial citrus pectin and pectin extracted from pomelo (Citrus maxima) peel. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 83, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereyra, R.B.; Gonzalez Vidal, N.L. Amiodarone chewable gels as a potential appproach for paediatric congenital cardiopathies treatment: Comparison between animal and vegetal gelling agents. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2024, 201, 114370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neis, J.S.; Zamberlan, A.M.; Saraiva, E.S.; Costa Pommer, E.; Dias, M.S.; Ferreira, L.M.; Adams, A.I.H. Pediatric-friendly suspension for oral administration of pyrimethamine in congenital toxoplasmosis: Development and in use-stability study. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 102, 106427. [Google Scholar]

- Chachlioutaki, K.; Tzimtzimis, E.K.; Tzetzis, D.; Chang, M.-W.; Ahmad, Z.; Karavasili, C.; Fatouros, D.G. Electrospun Orodispersible Films of Isoniazid for Pediatric Tuberculosis Treatment. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieser, K.; Emanuelli, J.; Daudt, R.M.; Bilatto, S.; Willig, J.B.; Guterres, S.S.; Pohlmann, A.R.; Buffon, A.; Correa, D.S.; Külkamp-Guerreiro, I.C. Taste-masked nanoparticles containing Saquinavir for pediatric oral administration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 117, 111315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, G.M.; Musazzi, M.U.; Francesca, S.; Silvia, F.; Paola, M.; Cilurzo, F. Extemporaneous printing of diclofenac orodispersible films for pediatrics. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2021, 47, 636–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.P.; Hendricks-Wenger, A.; Stewart, C.; Boone, K.; Futtrell-Peoples, N.; Kennedy, L.; Barker, E.D. Establishing Novel Doxorubicin-Loaded Polysaccharide Hydrogel for Controlled Drug Delivery for Treatment of Pediatric Brain Tumors. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogaji, I.J.; Hoag, S.W. Effect of Grewia Gum as a Suspending Agent on Ibuprofen Pediatric Formulation. AAPS PharmSciTech 2011, 12, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, L.; Garthoff, J.A.; Schaafsma, A.; Krul, L.; Schrijver, J.; van Goudoever, J.B.; Speijers, G.; Vandenplas, Y. Locust bean gum safety in neonates and young infants: An integrated review of the toxicological database and clinical evidence. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2014, 70, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Yang, M.; Ma, L.; Liu, X.; Ding, Q.; Chai, G.; Lu, Y.; Wei, H.; Zhang, S.; Ding, C. Structural modification and biological activity of polysaccharides. Molecules 2023, 28, 5416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Chi, C.; Pu, Y.; Miao, S.; Liu, D. Conjugation of soy protein isolate (SPI) with pectin: Effects of structural modification of the grafting polysaccharide. Food Chem. 2022, 387, 132876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Kumar, A. Graft and crosslinked polymerization of polysaccharide gum to form hydrogel wound dressings for drug delivery applications. Carbohydr. Res. 2020, 489, 107949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yang, L.; Wang, B.; Luo, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, F.; Xiang, X. Development, in vitro and in vivo evaluation of racecadotril orodispersible films for pediatric use. AAPS PharmSciTech 2021, 22, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alayoubi, A.; Haynes, L.; Patil, H.; Daihom, B.; Helms, R.; Almoazen, H. Development of a fast dissolving film of epinephrine hydrochloride as a potential anaphylactic treatment for pediatrics. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2017, 22, 1012–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gala, R.P.; Popescu, C.; Knipp, G.T.; McCain, R.R.; Ubale, R.V.; Addo, R.; Bhowmik, T.; Kulczar, C.D.; D’Souza, M.J. Physicochemical and preclinical evaluation of a novel buccal measles vaccine. AAPS PharmSciTech 2017, 18, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Puri, V.; Sharma, A.; Dheer, D.; Kesharwani, P. Recent update on the chemical modalities of mucoadhesive biopolymeric systems for safe and effective drug delivery. Appl. Mater. Today 2025, 44, 102690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sahu, R.K.; Chameettachal, S.; Pati, F.; Kumar, A. Fabrication and analysis of chitosan oligosaccharide based mucoadhesive patch for oromucosal drug delivery. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2022, 48, 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alopaeus, J.F.; Hellfritzsch, M.; Gutowski, T.; Scherließ, R.; Almeida, A.; Sarmento, B.; Škalko-Basnet, N.; Tho, I. Mucoadhesive buccal films based on a graft co-polymer–A mucin-retentive hydrogel scaffold. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 142, 105142. [Google Scholar]

- Račić, A.; Čalija, B.; Milić, J.; Milašinović, N.; Krajišnik, D. Development of polysaccharide-based mucoadhesive ophthalmic lubricating vehicles: The effect of different polymers on physicochemical properties and functionality. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2019, 49, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcantara, K.P.; Nalinratana, N.; Chutiwitoonchai, N.; Castillo, A.L.; Banlunara, W.; Vajragupta, O.; Rojsitthisak, P.; Rojsitthisak, P. Enhanced nasal deposition and anti-coronavirus effect of favipiravir-loaded mucoadhesive chitosan–alginate nanoparticles. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, L.; Xu, D.; Zhou, Y.-M.; Zhang, Y.-B.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.-B.; Cui, Y.-L. Antioxidant activities of natural polysaccharides and their derivatives for biomedical and medicinal applications. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabeen, N.; Atif, M. Polysaccharides based biopolymers for biomedical applications: A review. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2024, 35, e6203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Shen, M.; Song, Q.; Xie, J. Biological activities and pharmaceutical applications of polysaccharide from natural resources: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 183, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aluani, D.; Tzankova, V.; Kondeva-Burdina, M.; Yordanov, Y.; Nikolova, E.; Odzhakov, F.; Apostolov, A.; Markova, T.; Yoncheva, K. Еvaluation of biocompatibility and antioxidant efficiency of chitosan-alginate nanoparticles loaded with quercetin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 103, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wallach, M.; Krishna, A.; Kurmasheva, R.; Sridhar, S. Recent developments in nanomedicine for pediatric cancer. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, A.; Wu, C.-H.; Gonzales-Gomez, I.; Kwon-Chung, K.J.; Chang, Y.C.; Tseng, H.-K.; Cho, W.-L.; Huang, S.-H. Hyaluronic acid receptor CD44 deficiency is associated with decreased Cryptococcus neoformans brain infection. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 15298–15306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Lee, K.; Park, T.G. Hyaluronic acid—paclitaxel conjugate micelles: Synthesis, characterization, and antitumor activity. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008, 19, 1319–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsairat, H.; Lafi, Z.; Al-Najjar, B.O.; Al-Samydai, A.; Saqallah, F.G.; El-Tanani, M.; Oriquat, G.A.; Sa’bi, B.M.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Dellinger, A.L. How advanced are self-assembled nanomaterials for targeted drug delivery? A comprehensive review of the literature. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 2133–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Tian, J.; Wang, L.; Wen, C.; Song, S. Polyelectrolyte complex formation of alginate and chito oligosaccharide is influenced by their proportion and alginate molecular weight. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 273, 133173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhou, K.; Chen, D.; Xu, W.; Tao, Y.; Pan, Y.; Meng, K.; Shabbir, M.A.B.; Liu, Q.; Huang, L. Solid lipid nanoparticles with enteric coating for improving stability, palatability, and oral bioavailability of enrofloxacin. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 1619–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visan, A.I.; Cristescu, R. Polysaccharide-based coatings as drug delivery systems. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berradi, A.; Aziz, F.; Achaby, M.E.; Ouazzani, N.; Mandi, L. A comprehensive review of polysaccharide-based hydrogels as promising biomaterials. Polymers 2023, 15, 2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsarov, P.; Shindova, M.; Lukova, P.; Belcheva, A.; Delattre, C.; Pilicheva, B. Polysaccharide-based micro-and nanosized drug delivery systems for potential application in the pediatric dentistry. Polymers 2021, 13, 3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.; Silva, F.C.; Simões, S.; Ribeiro, H.M.; Almeida, A.J.; Marto, J. Innovative, sugar-free oral hydrogel as a co-administrative vehicle for pediatrics: A strategy to enhance patient compliance. AAPS PharmSciTech 2022, 23, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, B.; Arbab, A.; Khan, S.; Fatima, H.; Bibi, I.; Chowdhry, N.P.; Ansari, A.Q.; Ursani, A.A.; Kumar, S.; Hussain, J. Recent progress in thermosensitive hydrogels and their applications in drug delivery area. MedComm–Biomater. Appl. 2023, 2, e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ta, H.T.; Dass, C.R.; Larson, I.; Choong, P.F.; Dunstan, D.E. A chitosan hydrogel delivery system for osteosarcoma gene therapy with pigment epithelium-derived factor combined with chemotherapy. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 4815–4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, B.H.; Wu, F.G. Hydrogel-based growth factor delivery platforms: Strategies and recent advances. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2210707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, R.; Ola, M.; Khade, S.; Pawar, A.; Tikhe, R.; Madwe, V.; Shinde, S. Oral Thin Films: A Modern Frontier in Drug Delivery Systems. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2025, 15, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Liu, X.; Zhang, S.; Quan, D. An overview of taste-masking technologies: Approaches, application, and assessment methods. AAPS PharmSciTech 2023, 2, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.; Barot, S. Advances in Taste-Masking Strategies for Pediatric Brain-Related Disease Treatments: Focus on Polymeric Coatings in Orally Disintegrating Tablets. Int. J. Sci. R. Tech. 2025, 2, 437–452. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, M.T.; Tzortzis, G.; Khutoryanskiy, V.V.; Charalampopoulos, D. Layer-by-layer coating of alginate matrices with chitosan–alginate for the improved survival and targeted delivery of probiotic bacteria after oral administration. J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 1, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khotimchenko, M. Pectin polymers for colon-targeted antitumor drug delivery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 158, 1110–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, S.; Boddu, S.H.; Bhandare, R.; Ahmad, S.S.; Nair, A.B. Orodispersible films: Current innovations and emerging trends. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soubhagya, A.; Balagangadharan, K.; Selvamurugan, N.; Sathya Seeli, D.; Prabaharan, M. Preparation and characterization of chitosan/carboxymethyl pullulan/bioglass composite films for wound healing. J. Biomater. Appl. 2022, 36, 1151–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crona, D.J.; Faso, A.; Nishijima, T.F.; McGraw, K.A.; Galsky, M.D.; Milowsky, M.I. A systematic review of strategies to prevent cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Oncologist 2017, 22, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.B.; Chow, E.J.; Hjorth, L.; Hudson, M.M.; Kremer, L.C.; Morton, L.M.; Nathan, P.C.; Ness, K.K.; Oeffinger, K.C.; Armstrong, G.T. The future of childhood cancer survivorship: Challenges and opportunities for continued progress. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 67, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benning, T.J.; Shah, N.D.; Inselman, J.W.; Van Houten, H.K.; Ross, J.S.; Wyatt, K.D. Drug labeling changes and pediatric hematology/oncology prescribing: Measuring the impact of US legislation. Clin. Trials 2021, 18, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, M.R.; Liu, W.; Michelich, C.R.; Dewhirst, M.W.; Yuan, F.; Chilkoti, A. Tumor vascular permeability, accumulation, and penetration of macromolecular drug carriers. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2006, 98, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, E.A.; Rechberger, J.S.; Gupta, S.; Schwartz, J.D.; Daniels, D.J.; Khatua, S. Drug delivery across the blood-brain barrier for the treatment of pediatric brain tumors–An update. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2022, 185, 114303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; Faix, P.H.; Schnitzer, J.E. Overcoming key biological barriers to cancer drug delivery and efficacy. J. Control. Release 2017, 267, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, P.; Yang, K.; Tong, G.; Ma, L. Polysaccharide nanoparticles for targeted cancer therapies. Curr. Drug Metab. 2018, 19, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dattilo, M.; Patitucci, F.; Prete, S.; Parisi, O.I.; Puoci, F. Polysaccharide-based hydrogels and their application as drug delivery systems in cancer treatment: A review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajpurohit, H.; Sharma, S. Polymers for Colon Targeted Drug Delivery. J. Pharm. Sci. Technol. 2010, 62, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, V.R.; Kumria, R. Polysaccharides in colon-specific drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2001, 224, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryam, S.; Krukiewicz, K. Sweeten the pill: Multi-faceted polysaccharide-based carriers for colorectal cancer treatment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 136696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javid, H.; Oryani, M.A.; Rezagholinejad, N.; Esparham, A.; Tajaldini, M.; Karimi-Shahri, M. RGD peptide in cancer targeting: Benefits, challenges, solutions, and possible integrin–RGD interactions. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e6800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanović, B.; Fagret, D.; Ghezzi, C.; Montemagno, C. Integrin Targeting and Beyond: Enhancing Cancer Treatment with Dual-Targeting RGD (Arginine–Glycine–Aspartate) Strategies. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzoni, S.; Rodríguez-Nogales, C.; Blanco-Prieto, M.J. Targeting tumor microenvironment with RGD-functionalized nanoparticles for precision cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2025, 614, 217536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálisová, A.; Jirátová, M.; Rabyk, M.; Sticová, E.; Hájek, M.; Hrubý, M.; Jirák, D. Glycogen as an advantageous polymer carrier in cancer theranostics: Straightforward in vivo evidence. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Sood, A.; Fuhrer, E.; Djanashvili, K.; Agrawal, G. Polysaccharide-based theranostic systems for combined imaging and cancer therapy: Recent advances and challenges. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 8, 2281–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saletta, F.; Wadham, C.; Ziegler, D.S.; Marshall, G.M.; Haber, M.; McCowage, G.; Norris, M.D.; Byrne, J.A. Molecular profiling of childhood cancer: Biomarkers and novel therapies. BBA Clin. 2014, 1, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwaan, C.M.; Kolb, E.A.; Reinhardt, D.; Abrahamsson, J.; Adachi, S.; Aplenc, R.; De Bont, E.S.; De Moerloose, B.; Dworzak, M.; Gibson, B.E. Collaborative efforts driving progress in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 2949–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gröbner, S.N.; Worst, B.C.; Weischenfeldt, J.; Buchhalter, I.; Kleinheinz, K.; Rudneva, V.A.; Johann, P.D.; Balasubramanian, G.P.; Segura-Wang, M.; Brabetz, S. The landscape of genomic alterations across childhood cancers. Nature 2018, 555, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, G.M.; Carter, D.R.; Cheung, B.B.; Liu, T.; Mateos, M.K.; Meyerowitz, J.G.; Weiss, W.A. The prenatal origins of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, L.; Pearson, A.D.; Paoletti, X.; Jimenez, I.; Geoerger, B.; Kearns, P.R.; Zwaan, C.M.; Doz, F.; Baruchel, A.; Vormoor, J. Early phase clinical trials of anticancer agents in children and adolescents—An ITCC perspective. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 497–507. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, S.; Guchelaar, H.; Boven, E. The role of pharmacogenetics in capecitabine efficacy and toxicity. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2016, 50, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossig, C.; Juergens, H.; Berdel, W.E. New targets and targeted drugs for the treatment of cancer: An outlook to pediatric oncology. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2011, 28, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meel, R.; Sulheim, E.; Shi, Y.; Kiessling, F.; Mulder, W.J.; Lammers, T. Smart cancer nanomedicine. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, A.D.; Herold, R.; Rousseau, R.; Copland, C.; Bradley-Garelik, B.; Binner, D.; Capdeville, R.; Caron, H.; Carleer, J.; Chesler, L. Implementation of mechanism of action biology-driven early drug development for children with cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2016, 62, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classification | Polymer Examples | Origin and Description | Representative Derivatives and Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural | Alginate (ALG), Hyaluronic Acid (HA), Starch, Dextran | Directly extracted from natural sources (seaweed, animal tissues, plants, or microbial fermentation). They possess inherent biocompatibility and biodegradability [20]. | Alginate: In situ gelling systems, microencapsulation. Hyaluronic Acid: Ophthalmic solutions, tissue engineering scaffolds. Starch/Dextran: Plasma expanders, nanoparticle cores. |

| Semi-Synthetic | Chitosan, Cellulose Derivatives (e.g., HPMC, CMC), Modified Starches | Derived from natural polymers through chemical modification (e.g., deacetylation, etherification, esterification) to enhance solubility, stability, or functionality [21,22]. | Chitosan: Mucoadhesive nanoparticles, permeation enhancers. HPMC/CMC: Tablet binders, film-forming agents, viscosity modifiers. Modified Starches: Hydrogels, sustained-release matrices. |

| Synthetic | Poly (vinyl alcohol) (PVA), Poly (ethylene glycol) (PEG) | Fully synthesized in the laboratory. While not polysaccharides, they are often conjugated to natural polysaccharides to create hybrid systems with enhanced properties [23]. | PEGylated Polysaccharides: Used to prolong systemic circulation time (stealth effect) of nanocarriers, improving pharmacokinetics. |

| Route | Polymer | Pros | Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan/Alginate Mini-tablets, ODFs | High Acceptability | Taste Masking |

| Hyaluronic acid Nebulized | Reduced inflammation | Particle size, compatibility with inhalation devices |

| Chitosan/Hyaluronic acid Gels, Creams | Skin permeability | Skin permeability variability |

| Alginate-coated nanoparticles | CNS targeting | Regulatory and ethical aspects |

| Polysaccharide | Formulation Type | Target Disease/Use | Age Group | Study Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pectin | Oral suspension | Pain management | Children | [139] |

| Chewable gel | Congenital cardiopathies treatment | Children | [140] | |

| Carrageenan | Nasal spray | Common cold | Pediatric | [35] |

| Oral gel | Epilepsy | Children | [128] | |

| Oral jelly | Aiding solid dosage swallowing (non-specific) | Children with dysphagia | [32] | |

| Xanthan gum | Oral gel | Sleep disturbances | Children | [33] |

| Oral suspension | Congenital toxoplasmosis | Pediatric | [141] | |

| Oral suspension | Type 2 diabetes | Infants/Children | [32] | |

| Pullulan | Orodispersible film | Tuberculosis | Children | [142] |

| Oral suspension | HIV/AIDS | Pediatric | [143] | |

| Maltodextrin | Orodispersible film | Pain management | Children | [144] |

| Amylopectin | Hydrogel | Medulloblastoma | Pediatric | [145] |

| Grewia gum | Oral suspension | Pain management | Pediatric | [146] |

| Gellan gum | Semi-solid (pudding-like gel) | Aiding swallowing of oral medications (non-specific) | Children with dysphagia | [32] |

| Locust bean gum | Thickened infant formula | Gastroesophageal reflux | Neonates and infants | [147] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Račić, A.; Gatarić, B.; Topić Vučenović, V.; Stojmenovski, A. Polysaccharide-Based Drug Delivery Systems in Pediatrics: Addressing Age-Specific Challenges and Therapeutic Applications. Polysaccharides 2025, 6, 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040108

Račić A, Gatarić B, Topić Vučenović V, Stojmenovski A. Polysaccharide-Based Drug Delivery Systems in Pediatrics: Addressing Age-Specific Challenges and Therapeutic Applications. Polysaccharides. 2025; 6(4):108. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040108

Chicago/Turabian StyleRačić, Anđelka, Biljana Gatarić, Valentina Topić Vučenović, and Aneta Stojmenovski. 2025. "Polysaccharide-Based Drug Delivery Systems in Pediatrics: Addressing Age-Specific Challenges and Therapeutic Applications" Polysaccharides 6, no. 4: 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040108

APA StyleRačić, A., Gatarić, B., Topić Vučenović, V., & Stojmenovski, A. (2025). Polysaccharide-Based Drug Delivery Systems in Pediatrics: Addressing Age-Specific Challenges and Therapeutic Applications. Polysaccharides, 6(4), 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040108