Nutritional Approaches to Enhance GLP-1 Analogue Therapy in Obesity: A Narrative Review

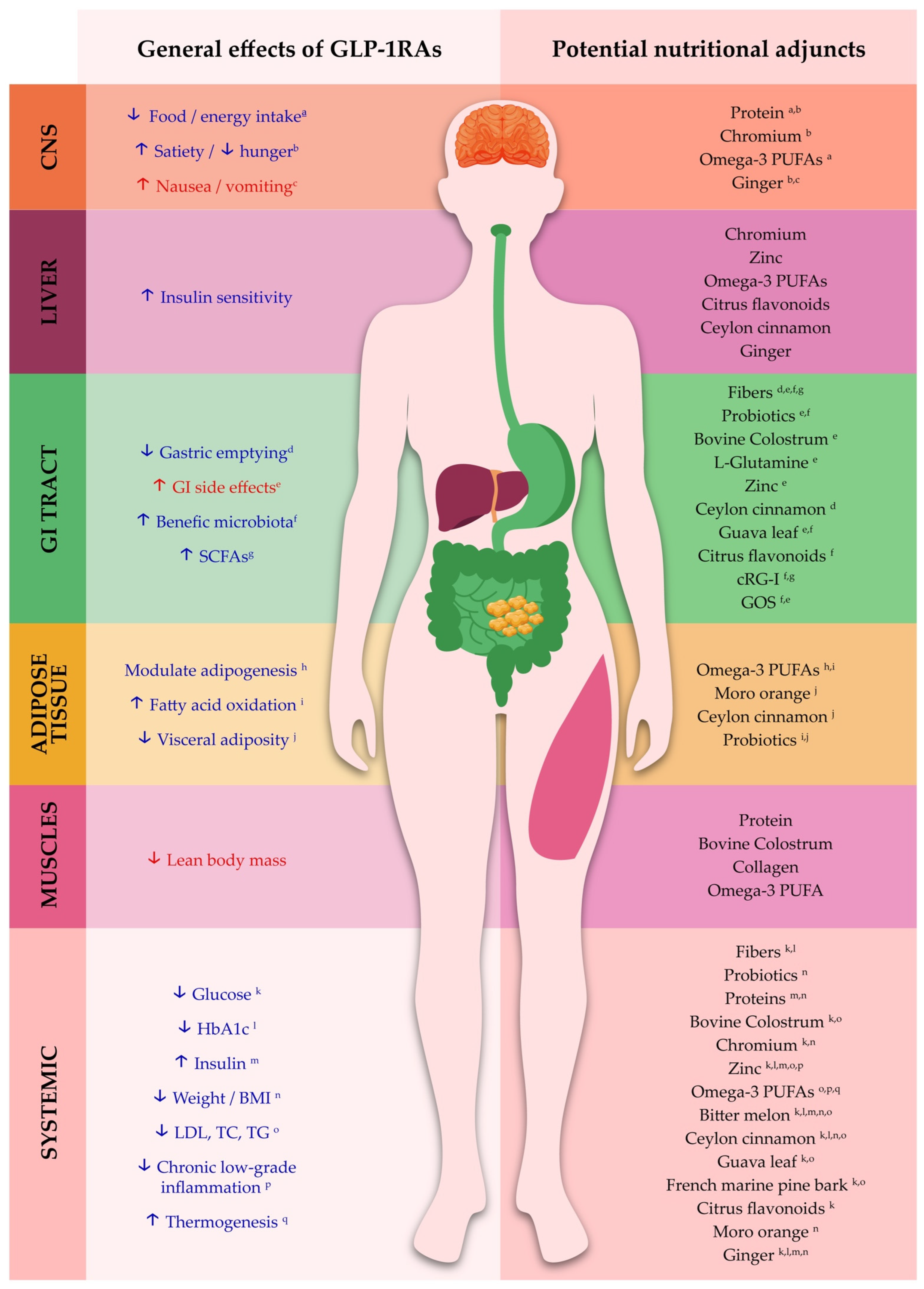

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists Therapy in Obesity Management

3. Integrating Nutritional Strategies into GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Therapy

3.1. Dietary Fibers and Prebiotics

3.2. Probiotics

3.3. Protein Sources

3.4. Specific Nutrients

3.4.1. Chromium

3.4.2. L-Glutamine

3.4.3. Zinc

3.4.4. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids

3.5. Botanical Actives

3.5.1. Bitter Melon (Momordica charantia) Extract

3.5.2. Ceylon Cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum) Extract

3.5.3. Guava (Psidium guajava) Leaf Extract

3.5.4. French Maritime Pine (Pinus pinaster) Bark Extract

3.5.5. Citrus Flavonoids

3.5.6. Moro Orange (Citrus sinensis L. Osbeck) Extract

3.5.7. Ginger (Zingiber officinale)

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Batista Filho, M. Análise da Política de Alimentação e Nutrição no Brasil: 20 anos de história. Cad. Saúde Pública 2021, 37, e00038721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Obesity and Overweight. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Escoda, M.D.S.Q. Para a crítica da transição nutricional. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 2002, 7, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, M.; Fleming, T.; Robinson, M.; Thomson, B.; Graetz, N.; Margono, C.; Mullany, E.C.; Biryukov, S.; Abbafati, C.; Abera, S.F.; et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014, 384, 766–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global burden and strength of evidence for 88 risk factors in 204 countries and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2162–2203. [CrossRef]

- Word Obesity. Atlas Mundial da Obesidade 2025. Available online: https://data.worldobesity.org/publications/PBO---Atlas-Mundial-da-Obesidade---WOF-2025-PT-BR.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Welsh, P.; Polisecki, E.; Robertson, M.; Jahn, S.; Buckley, B.M.; de Craen, A.J.; Ford, I.; Jukema, J.W.; Macfarlane, P.W.; Packard, C.J.; et al. Unraveling the directional link between adiposity and inflammation: A bidirectional Mendelian randomization approach. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic: Report of a WHO Consultation; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Muscogiuri, G.; Barrea, L.; Annunziata, G.; Di Somma, C.; Laudisio, D.; Colao, A.; Savastano, S. Obesity and sleep disturbance: The chicken or the egg? Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 2158–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, T.F.D.; Nahas, M.V.; Silva, D.A.S.; Del Duca, G.F.; Peres, M.A. Fatores associados à obesidade central em adultos de Florianópolis, Santa Catarina: Estudo de base populacional. Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 2011, 14, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabacow, F.M.; Azeredo, C.M.; Rezende, L.F.M. Deaths Attributable to High Body Mass in Brazil. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2019, 16, E141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Noncommunicable Diseases. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Brown, A.; Mellor, D.; Makaronidis, J.; Shuttlewood, E.; Miras, A.D.; Pournaras, D.J. “From evidence to practice”—Insights from the multidisciplinary team on the optimal integration of GLP-1 receptor agonists in obesity management services. Nutr. Bull. 2024, 49, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaseth, J.; Ellefsen, S.; Alehagen, U.; Sundfør, T.M.; Alexander, J. Diets and drugs for weight loss and health in obesity—An update. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 140, 111789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, D.B.; Almandoz, J.P.; Look, M. What is clinically relevant weight loss for your patients and how can it be achieved? A narrative review. Postgrad. Med. 2022, 134, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, S.; Robinson, K.; Thomas, S.; Williams, D.R. Dietary intake by patients taking GLP-1 and dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists: A narrative review and discussion of research needs. Obes. Pillars 2024, 11, 100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, I.; Khan, S.S.; Yeh, R.W.; Ho, J.E.; Dahabreh, I.J.; Kazi, D.S. Semaglutide Eligibility Across All Current Indications for US Adults. JAMA Cardiol. 2025, 10, 96–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmaleh-Sachs, A.; Schwartz, J.L.; Bramante, C.T.; Nicklas, J.M.; Gudzune, K.A.; Jay, M. Obesity Management in Adults: A Review. JAMA 2023, 330, 2000–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundbom, M.; Järvholm, K.; Sjögren, L.; Nowicka, P.; Lagerros, Y.T. Obesity treatment in adolescents and adults in the era of personalized medicine. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 296, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D. GLP-1 Agonists for Obesity—A New Recipe for Success? JAMA 2024, 331, 1007–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, A.; Sparks, G.; Presiado, M.; Hamel, L. KFF Health Tracking Poll—May 2024: The Public’s Use and Views of GLP-1 Drugs. 2024. Available online: https://www.kff.org/health-costs/kff-health-tracking-poll-may-2024-the-publics-use-and-views-of-glp-1-drugs/#d7b6969b-4b51-4aab-ad41-e2532f412570 (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Mozaffarian, D.; Agarwal, M.; Aggarwal, M.; Alexander, L.; Apovian, C.M.; Bindlish, S.; Bonnet, J.; Butsch, W.S.; Christensen, S.; Gianos, E.; et al. Nutritional priorities to support GLP-1 therapy for obesity: A joint advisory from the American College of Lifestyle Medicine, the American Society for Nutrition, the Obesity Medicine Association, and the Obesity Society. Obes. Pillars 2025, 15, 100181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, D.; Deckert, J.; Bartelt, K.; Ganesh, M.; Stamp, T. Weight Change with Semaglutide. 2023. Available online: https://media.epic.com/epicresearch/wordpressmedia/pdfs/diabetes-drug-helps-with-weight-loss-in-both-diabetics-and-non-diabetics.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Do, D.; Lee, T.; Peasah, S.K.; Good, C.B.; Inneh, A.; Patel, U. GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Discontinuation Among Patients With Obesity and/or Type 2 Diabetes. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2413172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleason, P.P.; Urick, B.Y.; Marshall, L.Z.; Friedlander, N.; Qiu, Y.; Leslie, R.S. Real-world persistence and adherence to glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists among obese commercially insured adults without diabetes. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2024, 30, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, P.J.; Goodwin Cartwright, B.M.; Gratzl, S.; Brar, R.; Baker, C.; Gluckman, T.J.; Stucky, N.L. Semaglutide vs Tirzepatide for Weight Loss in Adults With Overweight or Obesity. JAMA Intern. Med. 2024, 184, 1056–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despain, D.; Hoffman, B.L. Optimizing nutrition, diet, and lifestyle communication in GLP-1 medication therapy for weight management: A qualitative research study with registered dietitians. Obes. Pillars 2024, 12, 100143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, A.M.; Wadden, T.A.; Walsh, O.A.; Gruber, K.A.; Alamuddin, N.; Berkowitz, R.I.; Tronieri, J.S. Effects of Liraglutide and Behavioral Weight Loss on Food Cravings, Eating Behaviors, and Eating Disorder Psychopathology. Obesity 2019, 27, 2005–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadden, T.A.; Butryn, M.L.; Wilson, C. Lifestyle modification for the management of obesity. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 2226–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadden, T.A.; Bailey, T.S.; Billings, L.K.; Davies, M.; Frias, J.P.; Koroleva, A.; Lingvay, I.; O’Neil, P.M.; Rubino, D.M.; Skovgaard, D.; et al. Effect of Subcutaneous Semaglutide vs Placebo as an Adjunct to Intensive Behavioral Therapy on Body Weight in Adults With Overweight or Obesity: The STEP 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021, 325, 1403–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, D.J. Mechanisms of Action and Therapeutic Application of Glucagon-like Peptide-1. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 740–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, J.D.; Koumanov, F.; Gonzalez, J.T. Protein- and Calcium-Mediated GLP-1 Secretion: A Narrative Review. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 2540–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zong, Y.; Ma, Y.; Tian, Y.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gao, J. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: Mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, J.P. Intestinal glucagon-like peptide-1 effects on food intake: Physiological relevance and emerging mechanisms. Peptides 2020, 131, 170342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, T.; Sun, Z.; Pan, Y.; Deng, X.; Yuan, G. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1: New Regulator in Lipid Metabolism. Diabetes Metab. J. 2024, 48, 354–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheang, J.Y.; Moyle, P.M. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1)-Based Therapeutics: Current Status and Future Opportunities beyond Type 2 Diabetes. ChemMedChem 2018, 13, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabahizi, A.; Wallace, B.; Lieu, L.; Chau, D.; Dong, Y.; Hwang, E.S.; Williams, K.W. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) signalling in the brain: From neural circuits and metabolism to therapeutics. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 179, 600–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maselli, D.B.; Camilleri, M. Effects of GLP-1 and Its Analogs on Gastric Physiology in Diabetes Mellitus and Obesity. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1307, 171–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Zuylen, M.L.; Siegelaar, S.E.; Plummer, M.P.; Deane, A.M.; Hermanides, J.; Hulst, A.H. Perioperative management of long-acting glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists: Concerns for delayed gastric emptying and pulmonary aspiration. Br. J. Anaesth. 2024, 132, 644–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, T.D.; Finan, B.; Bloom, S.R.; D’Alessio, D.; Drucker, D.J.; Flatt, P.R.; Fritsche, A.; Gribble, F.; Grill, H.J.; Habener, J.F.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). Mol. Metab. 2019, 30, 72–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, D.J. Efficacy and Safety of GLP-1 Medicines for Type 2 Diabetes and Obesity. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, 1873–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.K. Mechanisms of action and therapeutic applications of GLP-1 and dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1431292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seino, Y.; Fukushima, M.; Yabe, D. GIP and GLP-1, the two incretin hormones: Similarities and differences. J. Diabetes Investig. 2010, 1, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samms, R.J.; Coghlan, M.P.; Sloop, K.W. How May GIP Enhance the Therapeutic Efficacy of GLP-1? Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 31, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavda, V.P.; Ajabiya, J.; Teli, D.; Bojarska, J.; Apostolopoulos, V. Tirzepatide, a New Era of Dual-Targeted Treatment for Diabetes and Obesity: A Mini-Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Htike, Z.Z.; Zaccardi, F.; Papamargaritis, D.; Webb, D.R.; Khunti, K.; Davies, M.J. Efficacy and safety of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and mixed-treatment comparison analysis. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2017, 19, 524–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Zhang, A.; Li, D.; Wu, Y.; Wang, C.Z.; Wan, J.Y.; Yuan, C.S. Comparative effectiveness of GLP-1 receptor agonists on glycaemic control, body weight, and lipid profile for type 2 diabetes: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ 2024, 384, e076410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Hu, J.; Gu, H.; Li, M.; Chen, J. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of 10 glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists as add-on to metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1244432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Hua, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Long, X.; Bai, Y.; Cheng, N. Efficacy and safety of GLP-1 agonists in the treatment of T2DM: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhou, Z.; Lyu, X.; Xu, H.; Zhu, H.; Pan, H.; Wang, L.; Yang, H.; Gong, F. The Antiobesity Effect and Safety of GLP-1 Receptor Agonist in Overweight/Obese Patients Without Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Horm. Metab. Res. 2022, 54, 458–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, H.U.H.; Qazi, S.U.; Sajid, F.; Altaf, Z.; Ghazanfar, S.; Naveed, N.; Ashfaq, A.S.; Siddiqui, A.H.; Iqbal, H.; Qazi, S. Efficacy and Safety of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists on Body Weight and Cardiometabolic Parameters in Individuals With Obesity and Without Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Endocr. Pract. 2024, 30, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, H.J.; Sim, B.; Teo, Y.H.; Teo, Y.N.; Chan, M.Y.; Yeo, L.L.L.; Eng, P.C.; Tan, B.Y.Q.; Sattar, N.; Dalakoti, M.; et al. Efficacy of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists on Weight Loss, BMI, and Waist Circumference for Patients With Obesity or Overweight: A Systematic Review, Meta-analysis, and Meta-regression of 47 Randomized Controlled Trials. Diabetes Care 2025, 48, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadda, K.R.; Cheng, T.S.; Ong, K.K. GLP-1 agonists for obesity and type 2 diabetes in children: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, P.M.; Seltzer, S.; Hayward, N.E.; Rodriguez, D.A.; Sless, R.T.; Hawkes, C.P. Safety and Efficacy of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in Children and Adolescents with Obesity: A Meta-Analysis. J. Pediatr. 2021, 236, 137–147.e113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olukorode, J.O.; Orimoloye, D.A.; Nwachukwu, N.O.; Onwuzo, C.N.; Oloyede, P.O.; Fayemi, T.; Odunaike, O.S.; Ayobami-Ojo, P.S.; Divine, N.; Alo, D.J.; et al. Recent Advances and Therapeutic Benefits of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) Agonists in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes and Associated Metabolic Disorders. Cureus 2024, 16, e72080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronne, L.J. Tirzepatide for Maintenance of Weight Reduction in Adults With Obesity-Reply. JAMA 2024, 331, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubino, D.; Abrahamsson, N.; Davies, M.; Hesse, D.; Greenway, F.L.; Jensen, C.; Lingvay, I.; Mosenzon, O.; Rosenstock, J.; Rubio, M.A.; et al. Effect of Continued Weekly Subcutaneous Semaglutide vs Placebo on Weight Loss Maintenance in Adults With Overweight or Obesity: The STEP 4 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021, 325, 1414–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilding, J.P.H.; Batterham, R.L.; Davies, M.; Van Gaal, L.F.; Kandler, K.; Konakli, K.; Lingvay, I.; McGowan, B.M.; Oral, T.K.; Rosenstock, J.; et al. Weight regain and cardiometabolic effects after withdrawal of semaglutide: The STEP 1 trial extension. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2022, 24, 1553–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, W.; Song, X.; Mohamed, Y.; Walsh, D.; Parks, E.J.; McMahon, T.M.; Khan, M.; Waitman, L.R. Medications and conditions associated with weight loss in patients prescribed semaglutide based on real-world data. Obesity 2023, 31, 2482–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentinetta, S.; Sottotetti, F.; Manuelli, M.; Cena, H. Dietary Recommendations for the Management of Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Patients Treated with GLP-1 Receptor Agonist. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2024, 17, 4817–4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorgojo-Martínez, J.J.; Mezquita-Raya, P.; Carretero-Gómez, J.; Castro, A.; Cebrián-Cuenca, A.; de Torres-Sánchez, A.; García-de-Lucas, M.D.; Núñez, J.; Obaya, J.C.; Soler, M.J.; et al. Clinical Recommendations to Manage Gastrointestinal Adverse Events in Patients Treated with Glp-1 Receptor Agonists: A Multidisciplinary Expert Consensus. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioli, M.; D’Agostino, E.; Valerii, L.; Angelino, D.; Serafini, M.; De Cristofaro, P. Probiotics In Incretin-Based Therapy for Patient Living with Obesity: A Synergistic Approach. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 8, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Gou, L.; Peng, M.; Zheng, J.; Chen, L. Effects of soluble fiber supplementation on glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 1800–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, P.; Garg, P.K.; Bhattacharya, K. Psyllium Husk Positively Alters Gut Microbiota, Decreases Inflammation, and Has Bowel-Regulatory Action, Paving the Way for Physiologic Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterology 2024, 166, 545–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, P. Psyllium Husk Should Be Taken at Higher Dose with Sufficient Water to Maximize Its Efficacy. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behall, K.M. Dietary fiber: Nutritional lessons for macronutrient substitutes. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1997, 819, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Chey, W.D.; Imdad, A.; Almario, C.V.; Bharucha, A.E.; Diem, S.; Greer, K.B.; Hanson, B.; Harris, L.A.; Ko, C.; et al. American Gastroenterological Association-American College of Gastroenterology Clinical Practice Guideline: Pharmacological Management of Chronic Idiopathic Constipation. Gastroenterology 2023, 164, 1086–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Man, S.; Wang, H.; Gao, C.; Li, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Lu, F. Dysregulation of intestinal flora: Excess prepackaged soluble fibers damage the mucus layer and induce intestinal inflammation. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 8558–8571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, N.; Gianfredi, V.; Solmi, M.; Barbagallo, M.; Dominguez, L.J.; Mandalà, C.; Di Palermo, C.; Carruba, L.; Solimando, L.; Stubbs, B.; et al. The impact of dietary fiber consumption on human health: An umbrella review of evidence from 17,155,277 individuals. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 51, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veronese, N.; Solmi, M.; Caruso, M.G.; Giannelli, G.; Osella, A.R.; Evangelou, E.; Maggi, S.; Fontana, L.; Stubbs, B.; Tzoulaki, I. Dietary fiber and health outcomes: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 107, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partula, V.; Deschasaux, M.; Druesne-Pecollo, N.; Latino-Martel, P.; Desmetz, E.; Chazelas, E.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Julia, C.; Fezeu, L.K.; Galan, P.; et al. Associations between consumption of dietary fibers and the risk of cardiovascular diseases, cancers, type 2 diabetes, and mortality in the prospective NutriNet-Santé cohort. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Abbeele, P.; Duysburgh, C.; Cleenwerck, I.; Albers, R.; Marzorati, M.; Mercenier, A. Consistent Prebiotic Effects of Carrot RG-I on the Gut Microbiota of Four Human Adult Donors in the SHIME(®) Model despite Baseline Individual Variability. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Abbeele, P.; Deyaert, S.; Albers, R.; Baudot, A.; Mercenier, A. Carrot RG-I Reduces Interindividual Differences between 24 Adults through Consistent Effects on Gut Microbiota Composition and Function Ex Vivo. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercenier, A.; Vu, L.D.; Poppe, J.; Albers, R.; McKay, S.; Van den Abbeele, P. Carrot-Derived Rhamnogalacturonan-I Consistently Increases the Microbial Production of Health-Promoting Indole-3-Propionic Acid Ex Vivo. Metabolites 2024, 14, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerezoudi, E.N.; McKay, S.; Kurt, S.; De Kreek, M.; De Medts, J.; Verstrepen, L.; Ghyselinck, J.; Van Meulebroek, L.; Calame, W.; Mercenier, A.; et al. Carrot Rhamnogalacturonan-I Supplementation Shapes Gut Microbiota and Immune Responses: A Randomised Trial in Healthy Adults. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Safety of rhamnogalacturonan-I enriched carrot fibre (cRG-I) as a novel food pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. EFSA J. 2025, 23, e9537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonker, D.; Fowler, P.; Albers, R.; Tzoumaki, M.V.; van het Hof, K.H.; Aparicio-Vergara, M. Safety assessment of rhamnogalacturonan-enriched carrot pectin fraction: 90-Day oral toxicity study in rats and in vitro genotoxicity studies. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 139, 111243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA. Safety of the extension of use of galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS) as a novel food in food for special medical purposes pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. EFSA J. 2022, 20, e07203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, J.C.; Merriman, T.N.; Heimbach, J.T. 90-Day oral (gavage) study in rats with galactooligosaccharides syrup. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2006, 44, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, T.; Yasutake, N.; Uchida, K.; Ohyama, W.; Kaneko, K.; Onoue, M. Safety of a novel galacto-oligosaccharide: Genotoxicity and repeated oral dose studies. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2009, 28, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Takano, M.; Kaneko, K.; Onoue, M. A one-generation reproduction toxicity study in rats treated orally with a novel galacto-oligosaccharide. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2014, 33, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.V.B.; Milstead, M.; Kreider, R.; Jones, R. Dietary supplement considerations during glucagon-like Peptide-1 receptor agonist treatment: A narrative review. Obes. Pillars 2025, 16, 100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.U. Clinical Uses of Probiotics. Medicine 2016, 95, e2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katkowska, M.; Garbacz, K.; Kusiak, A. Probiotics: Should All Patients Take Them? Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cava, E.; Padua, E.; Campaci, D.; Bernardi, M.; Muthanna, F.M.S.; Caprio, M.; Lombardo, M. Investigating the Health Implications of Whey Protein Consumption: A Narrative Review of Risks, Adverse Effects, and Associated Health Issues. Healthcare 2024, 12, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Safety of Whey basic protein isolates as a novel food pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. EFSA J. 2018, 16, e05360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Nutritional safety and suitability of a specific protein hydrolysate manufactured by Fonterra Co-operative Group Ltd derived from a whey protein concentrate and used in infant formula and follow-on formula. EFSA J. 2025, 23, e9160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, F.-C.; Bukhsh, A.; Rehman, H.; Waqas, M.K.; Shahid, N.; Khaliel, A.M.; Elhanish, A.; Karoud, M.; Telb, A.; Khan, T.M. Efficacy and Safety of Whey Protein Supplements on Vital Sign and Physical Performance Among Athletes: A Network Meta-Analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siener, R. Nutrition and Kidney Stone Disease. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reilly, D.M.; Kynaston, L.; Naseem, S.; Proudman, E.; Laceby, D. A Clinical Trial Shows Improvement in Skin Collagen, Hydration, Elasticity, Wrinkles, Scalp, and Hair Condition following 12-Week Oral Intake of a Supplement Containing Hydrolysed Collagen. Dermatol. Res. Pract. 2024, 2024, 8752787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, F.D.; Sung, C.T.; Juhasz, M.L.; Mesinkovsk, N.A. Oral Collagen Supplementation: A Systematic Review of Dermatological Applications. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2019, 18, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Playford, R.J. The Use of Bovine Colostrum in Medical Practice and Human Health: Current Evidence and Areas Requiring Further Examination. Nutrients 2021, 14, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, G.; Jones, A.W.; Marchbank, T.; Playford, R.J. Oral bovine colostrum supplementation does not increase circulating insulin-like growth factor-1 concentration in healthy adults: Results from short- and long-term administration studies. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 1473–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, A.; Glávits, R.; Murbach, T.S.; Endres, J.R.; Reddeman, R.; Hirka, G.; Vértesi, A.; Béres, E.; Szakonyiné, I.P. Toxicological evaluations of colostrum ultrafiltrate. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2019, 104, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ODS. Chromium. Available online: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Chromium-HealthProfessional/ (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- EFSA. Scientific Opinion on the safety of chromium picolinate as a source of chromium added for nutritional purposes to foodstuff for particular nutritional uses and to foods intended for the general population. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suksomboon, N.; Poolsup, N.; Yuwanakorn, A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of chromium supplementation in diabetes. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2014, 39, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for chromium. EFSA J. 2014, 12, 3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, H.B.; Child, R.B.; Fallowfield, J.L.; Delves, S.K.; Westwood, C.S.; Millyard, A.; Layden, J.D. Gastrointestinal Tolerance of Low, Medium and High Dose Acute Oral l-Glutamine Supplementation in Healthy Adults: A Pilot Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, A.; Hathcock, J.N. Risk assessment for the amino acids taurine, L-glutamine and L-arginine. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2008, 50, 376–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for zinc. EFSA J. 2014, 12, 3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ODS. Zinc. Available online: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Zinc-HealthProfessional/ (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Schoofs, H.; Schmit, J.; Rink, L. Zinc Toxicity: Understanding the Limits. Molecules 2024, 29, 3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BfR. Proposed Maximum Levels for the Addition of Zinc to Foods Including Food Supplements. 2021. Available online: https://www.bfr.bund.de/cm/349/proposed-maximum-levels-for-the-addition-of-zinc-to-foods-including-food-supplements.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- EFSA. Scientific Opinion on the Tolerable Upper Intake Level of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and docosapentaenoic acid (DPA). EFSA J. 2012, 10, 2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Safety of ‘Lipid extract from Euphausia superba’ as a novel food ingredient Safety of ‘Lipid extract from Euphausia superba’ as a novel food ingredient. EFSA J. 2009, 7, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, W.Y.; Jadhav, S.; Hsu, P.K.; Kuan, C.M. Evaluation of acute and sub-chronic toxicity of bitter melon seed extract in Wistar rats. Toxicol. Rep. 2022, 9, 1024–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe, P.; Pigera, S.; Premakumara, G.A.S.; Galappaththy, P.; Constantine, G.R.; Katulanda, P. Medicinal properties of ‘true’ cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum): A systematic review. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 13, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe, P.; Jayawardena, R.; Pigera, S.; Wathurapatha, W.S.; Weeratunga, H.D.; Premakumara, G.A.S.; Katulanda, P.; Constantine, G.R.; Galappaththy, P. Evaluation of pharmacodynamic properties and safety of Cinnamomum zeylanicum (Ceylon cinnamon) in healthy adults: A phase I clinical trial. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukuda, D.; de Silva, C.K.; Ajanthan, S.; Wijesinghe, N.; Dahanayaka, A.; Pathmeswaran, A. Effects of Cinnamomum zeylanicum (Ceylon cinnamon) extract on lipid profile, glucose levels and its safety in adults: A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0317904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, D.T.; Tung, T.H.; Jiesisibieke, Z.L.; Chien, C.W.; Liu, W.Y. Safety of Cinnamon: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews of Randomized Clinical Trials. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 790901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amadi, C.N.; Aghalibe, P.O. Evaluation of Drug-diet interaction between Psidium guajava (Guava) fruit and Metoclopramide. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2019, 9, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igwe, J.O.; Abone, H.O.; Ezea, M.C.; Ejikeugwu, C.P.; Esimone, C.O. Acute and chronic toxicity evaluation of methanol leaf extract of Psidium guajava (Myrtaceae). GSC Biol. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 16, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birdi, T.; Krishnan, G.G.; Kataria, S.; Gholkar, M.; Daswani, P. A randomized open label efficacy clinical trial of oral guava leaf decoction in patients with acute infectious diarrhoea. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2020, 11, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Jullian, V.; Chassagne, F. Ethnobotany, phytochemistry, and biological activities of Psidium guajava in the treatment of diarrhea: A review. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1459066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, L.; Penman, M.G.; Piriou, Y. Evaluation of the systemic toxicity and mutagenicity of OLIGOPIN®, procyanidolic oligomers (OPC) extracted from French Maritime Pine Bark extract. Toxicol. Rep. 2018, 5, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, C.B.; Ramos, F.M.; Manthey, J.A.; Cesar, T.B. Effectiveness of Eriomin® in managing hyperglycemia and reversal of prediabetes condition: A double-blind, randomized, controlled study. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 1921–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesar, T.B.; Ramos, F.M.M.; Ribeiro, C.B. Nutraceutical Eriocitrin (Eriomin) Reduces Hyperglycemia by Increasing Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 and Downregulates Systemic Inflammation: A Crossover-Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Med. Food 2022, 25, 1050–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicero-Sarmiento, C.G.; Ortiz-Andrade, R.; Araujo-León, J.A.; Segura-Campos, M.R.; Vazquez-Garcia, P.; Rubio-Zapata, H.; Hernández-Baltazar, E.; Yañez-Pérez, V.; Sánchez-Recillas, A.; Sánchez-Salgado, J.C.; et al. Preclinical Safety Profile of an Oral Naringenin/Hesperidin Dosage Form by In Vivo Toxicological Tests. Sci. Pharm. 2022, 90, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briskey, D.; Malfa, G.A.; Rao, A. Effectiveness of “Moro” Blood Orange Citrus sinensis Osbeck (Rutaceae) Standardized Extract on Weight Loss in Overweight but Otherwise Healthy Men and Women—A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardile, V.; Graziano, A.C.; Venditti, A. Clinical evaluation of Moro (Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck) orange juice supplementation for the weight management. Nat. Prod. Res. 2015, 29, 2256–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. Notice to US Food and Drug Administration of the Conclusion that the Intended Use of Citrus Sinensis Extract is Generally Recognized as Safe; FDA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Modi, M.; Modi, K. Ginger Root. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK565886/ (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- NIH. Ginger. In LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury; Bethesda, M., Ed.; NIH: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- COT. Statement on the Safety of Ginger Supplement Use in Pregnancy—Reviews by Other Risk Assessment Bodies. Available online: https://cot.food.gov.uk/Reviews%20by%20other%20risk%20assessment%20bodies%20-%20Statement%20on%20the%20Safety%20of%20Ginger%20Supplement%20Use%20in%20Pregnancy (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Ojo, O.; Feng, Q.Q.; Ojo, O.O.; Wang, X.H. The Role of Dietary Fibre in Modulating Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokubo, E.; Morita, S.; Nagashima, H.; Oshio, K.; Iwamoto, H.; Miyaji, K. Blood Glucose Response of a Low-Carbohydrate Oral Nutritional Supplement with Isomaltulose and Soluble Dietary Fiber in Individuals with Prediabetes: A Randomized, Single-Blind Crossover Trial. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, B.; Ren, L.; Du, H.; Fei, C.; Qian, C.; Li, B.; Zhang, R.; Liu, H.; Li, Z.; et al. High-fiber diet ameliorates gut microbiota, serum metabolism and emotional mood in type 2 diabetes patients. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1069954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Jia, W.; He, H.; Yin, J.; Xu, H.; He, C.; Zhang, Q.; Peng, Y.; Cheng, R. A New Dietary Fiber Can Enhance Satiety and Reduce Postprandial Blood Glucose in Healthy Adults: A Randomized Cross-Over Trial. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Yang, C.; Wai, S.T.C.; Zhang, Y.; Portillo, M.P.; Paoli, P.; Wu, Y.; San Cheang, W.; Liu, B.; Carpéné, C.; et al. Regulation of glucose metabolism by bioactive phytochemicals for the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 830–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaewdech, A.; Sripongpun, P.; Wetwittayakhlang, P.; Churuangsuk, C. The effect of fiber supplementation on the prevention of diarrhea in hospitalized patients receiving enteral nutrition: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials with the GRADE assessment. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1008464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Schoot, A.; Drysdale, C.; Whelan, K.; Dimidi, E. The Effect of Fiber Supplementation on Chronic Constipation in Adults: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 116, 953–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Abbeele, P.; Verstrepen, L.; Ghyselinck, J.; Albers, R.; Marzorati, M.; Mercenier, A. A Novel Non-Digestible, Carrot-Derived Polysaccharide (cRG-I) Selectively Modulates the Human Gut Microbiota while Promoting Gut Barrier Integrity: An Integrated In Vitro Approach. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, C.; Sorensen, N.; Lutter, R.; Albers, R.; de Vos, W.; Salonen, A.; Mercenier, A. The impact of daily supplementation with rhamnogalacturonan-I on the gut microbiota in healthy adults: A randomized controlled trial. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 174, 116561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depeint, F.; Tzortzis, G.; Vulevic, J.; I’Anson, K.; Gibson, G.R. Prebiotic evaluation of a novel galactooligosaccharide mixture produced by the enzymatic activity of Bifidobacterium bifidum NCIMB 41171, in healthy humans: A randomized, double-blind, crossover, placebo-controlled intervention study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergeev, I.N.; Aljutaily, T.; Walton, G.; Huarte, E. Effects of Synbiotic Supplement on Human Gut Microbiota, Body Composition and Weight Loss in Obesity. Nutrients 2020, 12, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silk, D.B.; Davis, A.; Vulevic, J.; Tzortzis, G.; Gibson, G.R. Clinical trial: The effects of a trans-galactooligosaccharide prebiotic on faecal microbiota and symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 29, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulevic, J.; Drakoularakou, A.; Yaqoob, P.; Tzortzis, G.; Gibson, G.R. Modulation of the fecal microflora profile and immune function by a novel trans-galactooligosaccharide mixture (B-GOS) in healthy elderly volunteers. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 1438–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drakoularakou, A.; Tzortzis, G.; Rastall, R.A.; Gibson, G.R. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized human study assessing the capacity of a novel galacto-oligosaccharide mixture in reducing travellers’ diarrhoea. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasle, G.; Raastad, R.; Bjune, G.; Jenum, P.A.; Heier, L. Can a galacto-oligosaccharide reduce the risk of traveller’s diarrhoea? A placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind study. J. Travel. Med. 2017, 24, tax057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, C.; Hunter, K.A.; Johnson, M.A.; Sharpe, G.R.; Gibson, G.R.; Walton, G.E.; Poveda, C.; Cousins, B.; Williams, N.C. Effects of 24-week prebiotic intervention on self-reported upper respiratory symptoms, gastrointestinal symptoms, and markers of immunity in elite rugby union players. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2023, 23, 2232–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, L.V. Meta-analysis of probiotics for the prevention of antibiotic associated diarrhea and the treatment of Clostridium difficile disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 101, 812–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.P.; Lee, K.M.; Kang, J.H.; Yun, S.I.; Park, H.O.; Moon, Y.; Kim, J.Y. Effect of Lactobacillus gasseri BNR17 on Overweight and Obese Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind Clinical Trial. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2013, 34, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Yun, J.M.; Kim, M.K.; Kwon, O.; Cho, B. Lactobacillus gasseri BNR17 Supplementation Reduces the Visceral Fat Accumulation and Waist Circumference in Obese Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Med. Food 2018, 21, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, S.I.; Park, H.O.; Kang, J.H. Effect of Lactobacillus gasseri BNR17 on blood glucose levels and body weight in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 107, 1681–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.H.; Yun, S.I.; Park, H.O. Effects of Lactobacillus gasseri BNR17 on body weight and adipose tissue mass in diet-induced overweight rats. J. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 712–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.H.; Yun, S.I.; Park, M.H.; Park, J.H.; Jeong, S.Y.; Park, H.O. Anti-obesity effect of Lactobacillus gasseri BNR17 in high-sucrose diet-induced obese mice. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuyul-Vásquez, I.; Pezo-Navarrete, J.; Vargas-Arriagada, C.; Ortega-Díaz, C.; Sepúlveda-Loyola, W.; Hirabara, S.M.; Marzuca-Nassr, G.N. Effectiveness of Whey Protein Supplementation during Resistance Exercise Training on Skeletal Muscle Mass and Strength in Older People with Sarcopenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Ye, X.; Ji, S.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Xiang, D.; Luo, B. Whey Protein Supplementation Combined with Exercise on Muscle Protein Synthesis and the AKT/mTOR Pathway in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piri Damaghi, M.; Mirzababaei, A.; Moradi, S.; Daneshzad, E.; Tavakoli, A.; Clark, C.C.T.; Mirzaei, K. Comparison of the effect of soya protein and whey protein on body composition: A meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 127, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Daza, D.; López-Ucrós, N.; Posada-Álvarez, C.; Savino-Lloreda, P. Effect of oral supplementation with whey protein on muscle mass in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Endocrinol. Diabetes Y Nutr. 2024, 71, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergia, R.E., 3rd; Hudson, J.L.; Campbell, W.W. Effect of whey protein supplementation on body composition changes in women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2018, 76, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonson, M.; Boirie, Y.; Guillet, C. Protein, amino acids and obesity treatment. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2020, 21, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.L.; Zhang, F.; Luo, H.Y.; Quan, Z.W.; Wang, Y.F.; Huang, L.T.; Wang, J.H. Improving sarcopenia in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of whey protein supplementation with or without resistance training. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2024, 28, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rawhani, A.H.; Adznam, S.N.; Zaid, Z.A.; Yusop, N.B.M.; Sallehuddin, H.M.; Alshawsh, M.A. Effectiveness of whey protein supplementation on muscle strength and physical performance of older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 43, 2412–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, K.J.; Cheah, L.J. Benefits and side effects of protein supplementation and exercise in sarcopenic obesity: A scoping review. Nutr. J. 2023, 22, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedegaard, S.; Kampmann, U.; Ovesen, P.G.; Støvring, H.; Rittig, N. Whey Protein Premeal Lowers Postprandial Glucose Concentrations in Adults Compared with Water-The Effect of Timing, Dose, and Metabolic Status: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 118, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, S.W.; Liu, H.W.; Loh, E.W.; Tam, K.W.; Wang, J.Y.; Huang, W.L.; Kuan, Y.C. Whey protein supplementation improves postprandial glycemia in persons with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr. Res. 2022, 104, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badely, M.; Sepandi, M.; Samadi, M.; Parastouei, K.; Taghdir, M. The effect of whey protein on the components of metabolic syndrome in overweight and obese individuals; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2019, 13, 3121–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amirani, E.; Milajerdi, A.; Reiner, Ž.; Mirzaei, H.; Mansournia, M.A.; Asemi, Z. Effects of whey protein on glycemic control and serum lipoproteins in patients with metabolic syndrome and related conditions: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Lipids Health Dis. 2020, 19, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, K.M.; Hansell, E.J.; Thorley, J.; Funnell, M.P.; Thackray, A.E.; Stensel, D.J.; Bailey, S.J.; James, L.J.; Prawitt, J.; Virgilio, N.; et al. The effects of collagen peptide supplementation on appetite and post-exercise energy intake in females: A randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2025, 134, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Yoldi, M.; Riezu-Boj, J.I.; Abete, I.; Ibero-Baraibar, I.; Aranaz, P.; González-Salazar, I.; Izco, J.M.; Recalde, J.I.; González-Navarro, C.J.; Milagro, F.I.; et al. Anti-Obesity Effects of a Collagen with Low Digestibility and High Swelling Capacity: A Human Randomized Control Trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.T.; Astrup, A.; Sjödin, A. Are Dietary Proteins the Key to Successful Body Weight Management? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Studies Assessing Body Weight Outcomes after Interventions with Increased Dietary Protein. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdzieblik, D.; Oesser, S.; Baumstark, M.W.; Gollhofer, A.; Konig, D. Collagen peptide supplementation in combination with resistance training improves body composition and increases muscle strength in elderly sarcopenic men: A randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 114, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jendricke, P.; Centner, C.; Zdzieblik, D.; Gollhofer, A.; König, D. Specific Collagen Peptides in Combination with Resistance Training Improve Body Composition and Regional Muscle Strength in Premenopausal Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2019, 11, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Kim, M.; Shin, H.; Ahn, H.; Park, Y.K. Low-Molecular Collagen Peptide Supplementation and Body Fat Mass in Adults Aged ≥ 50 Years: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Clin. Nutr. Res. 2023, 12, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oken, H.A.; Roizen, M.F.; Ryan, A.S.; Playford, R.J. Bovine Colostrum and Chicken Egg Reduce GLP-1 Induced Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Non-diabetic Subjects. Results of a Pilot Study. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2025, 9, 107242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Playford, R.J.; MacDonald, C.E.; Calnan, D.P.; Floyd, D.N.; Podas, T.; Johnson, W.; Wicks, A.C.; Bashir, O.; Marchbank, T. Co-administration of the health food supplement, bovine colostrum, reduces the acute non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced increase in intestinal permeability. Clin. Sci. 2001, 100, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajihashemi, P.; Haghighatdoost, F.; Kassaian, N.; Hoveida, L.; Tamizifar, B.; Nili, H.; Rahim Khorasani, M.; Adibi, P. Bovine Colostrum in Increased Intestinal Permeability in Healthy Athletes and Patients: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2024, 69, 1345–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Jung, W.S.; Choi, N.J.; Kim, D.O.; Shin, D.H.; Kim, Y.J. Health-promoting effects of bovine colostrum in Type 2 diabetic patients can reduce blood glucose, cholesterol, triglyceride and ketones. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2009, 20, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, J.; Sanders, M.S.; Van Gammeren, D. The effects of bovine colostrum supplementation on body composition and exercise performance in active men and women. Nutrition 2001, 17, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, C.; Taghizadeh, M.; Aghabagheri, E.; Asemi, Z.; Jafarnejad, S. A meta-analysis of the effect of chromium supplementation on anthropometric indices of subjects with overweight or obesity. Clin. Obes. 2019, 9, e12313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, S.D.; Morrison, C.D.; Cefalu, W.T.; Martin, C.K.; Coulon, S.; Geiselman, P.; Han, H.; White, C.L.; Williamson, D.A. Effects of Chromium Picolinate on Food Intake and Satiety. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2008, 10, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhalidi, F. A comparative study to assess the use of chromium in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Med. Life 2023, 16, 1178–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talab, A.T.; Abdollahzad, H.; Nachvak, S.M.; Pasdar, Y.; Eghtesadi, S.; Izadi, A.; Aghdashi, M.A.; Mohammad Hossseini Azar, M.R.; Moradi, S.; Mehaki, B.; et al. Effects of Chromium Picolinate Supplementation on Cardiometabolic Biomarkers in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin. Nutr. Res. 2020, 9, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Agrawal, R.P.; Choudhary, M.; Jain, S.; Goyal, S.; Agarwal, V. Beneficial effect of chromium supplementation on glucose, HbA1C and lipid variables in individuals with newly onset type-2 diabetes. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2011, 25, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deters, B.J.; Saleem, M. The role of glutamine in supporting gut health and neuropsychiatric factors. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2021, 10, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Verne, M.L.; Fields, J.Z.; Lefante, J.J.; Basra, S.; Salameh, H.; Verne, G.N. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of dietary glutamine supplements for postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 2019, 68, 996–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, F.; Haghighat Lari, M.M.; Khosravi, G.R.; Mansouri, E.; Payandeh, N.; Milajerdi, A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials on the effects of glutamine supplementation on gut permeability in adults. Amino Acids 2024, 56, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroni, M.L.; Brodosi, L.; Marchignoli, F.; Sasdelli, A.S.; Caraceni, P.; Marchesini, G.; Ravaioli, F. Nutrition in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: Present Knowledge and Remaining Challenges. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompano, L.M.; Boy, E. Effects of Dose and Duration of Zinc Interventions on Risk Factors for Type 2 Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Shaju, R.; Atfi, A.; Razzaque, M.S. Zinc and Diabetes: A Connection between Micronutrient and Metabolism. Cells 2024, 13, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoen, R.U.; Barther, N.N.; Schemitt, E.; Bona, S.; Fernandes, S.; Coral, G.; Marroni, N.P.; Tovo, C.; Guedes, R.P.; Porawski, M. Zinc supplementation reduces diet-induced obesity and improves insulin sensitivity in rats. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 44, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, H.C. Zinc Deficiency and Therapeutic Value of Zinc Supplementation in Pediatric Gastrointestinal Diseases. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.A.; Naqvi, S.K.; Hasnain, Z.; Zubairi, M.B.A.; Sharif, A.; Salam, R.A.; Soofi, S.; Ariff, S.; Nisar, Y.B.; Das, J.K. Zinc supplementation for acute and persistent watery diarrhoea in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Glob. Health 2024, 14, 04212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Angelo, S.; Motti, M.L.; Meccariello, R. ω-3 and ω-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids, Obesity and Cancer. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Liu, W.; Zhao, T.Y.; Tian, H.M. Efficacy of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids supplementation in managing overweight and obesity: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2017, 21, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albracht-Schulte, K.; Kalupahana, N.S.; Ramalingam, L.; Wang, S.; Rahman, S.M.; Robert-McComb, J.; Moustaid-Moussa, N. Omega-3 fatty acids in obesity and metabolic syndrome: A mechanistic update. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2018, 58, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammone, M.A.; Riccioni, G.; Parrinello, G.; D’Orazio, N. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids: Benefits and Endpoints in Sport. Nutrients 2018, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.H.; Chiu, W.C.; Hsu, Y.P.; Lo, Y.L.; Wang, Y.H. Effects of Omega-3 Fatty Acids on Muscle Mass, Muscle Strength and Muscle Performance among the Elderly: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Baek, M.-O.; Khaliq, S.A.; Parveen, A.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, I.-C.; Yoon, M.-S. Antarctic krill extracts enhance muscle regeneration and muscle function via mammalian target of rapamycin regulation. J. Funct. Foods 2023, 103, 105483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therdyothin, A.; Prokopidis, K.; Galli, F.; Witard, O.C.; Isanejad, M. The effects of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on muscle and whole-body protein synthesis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2024, 83, e131–e143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.N.; Lu, K.N.; Pai, Y.P.; Chin, H.; Huang, C.J. Role of GLP-1 in the Hypoglycemic Effects of Wild Bitter Gourd. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 625892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phimarn, W.; Sungthong, B.; Saramunee, K.; Caichompoo, W. Efficacy of Momordica charantia L. on blood glucose, blood lipid, and body weight: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2018, 14, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mes, J.J.; van den Belt, M.; van der Haar, S.; Oosterink, E.; Luijendijk, T.; Manusama, K.; van Dam, L.; de Bie, T.; Witkamp, R.; Esser, D. Bitter gourd (Momordica charantia L.) supplementation for twelve weeks improves biomarkers of glucose homeostasis in a prediabetic population. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 347, 119756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarneiri, L.L.; Wilcox, M.L.; Kuan, C.M.; Maki, K.C. Investigation of the Influence of a Bitter Melon Product on Indicators of Cardiometabolic Health in Adults with Prediabetes. J. Am. Nutr. Assoc. 2025, 44, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.; Jung, J.; Jung, J.H.; Yoon, N.; Kang, S.S.; Roh, G.S.; Hahm, J.R. Hypoglycemic efficacy and safety of Momordica charantia (bitter melon) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 52, 102524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, E.L.; Kasali, F.M.; Deyno, S.; Mtewa, A.; Nagendrappa, P.B.; Tolo, C.U.; Ogwang, P.E.; Sesaazi, D. Momordica charantia L. lowers elevated glycaemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 231, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amini, M.R.; Rasaei, N.; Jalalzadeh, M.; Pourreza, S.; Hekmatdoost, A. The Effects of Bitter Melon (Mormordica charantia) on Lipid Profile: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Phytother. Res. 2024, 38, 5949–5961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, M.; Kim, E.K.; Choi, Y.J.; Tang, Y.; Moon, S.H. The Role of Momordica charantia in Resisting Obesity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.A.; Uddin, R.; Subhan, N.; Rahman, M.M.; Jain, P.; Reza, H.M. Beneficial role of bitter melon supplementation in obesity and related complications in metabolic syndrome. J. Lipids 2015, 2015, 496169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akilen, R.; Tsiami, A.; Devendra, D.; Robinson, N. Cinnamon in glycaemic control: Systematic review and meta analysis. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 31, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.M.; Rahmani, J.; Kord-Varkaneh, H.; Sheikhi, A.; Larijani, B.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Cinnamon supplementation positively affects obesity: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, R.; Nadjarzadeh, A.; Zarshenas, M.M.; Shams, M.; Heydari, M. Efficacy of cinnamon in patients with type II diabetes mellitus: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlebowicz, J.; Darwiche, G.; Björgell, O.; Almér, L.O. Effect of cinnamon on postprandial blood glucose, gastric emptying, and satiety in healthy subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 1552–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozoya, X.; Reyes-Morales, H.; Chávez-Soto, M.A.; Martínez-García Mdel, C.; Soto-González, Y.; Doubova, S.V. Intestinal anti-spasmodic effect of a phytodrug of Psidium guajava folia in the treatment of acute diarrheic disease. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 83, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simão, A.A.; Marques, T.R.; Marcussi, S.; Corrêa, A.D. Aqueous extract of Psidium guajava leaves: Phenolic compounds and inhibitory potential on digestive enzymes. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2017, 89, 2155–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deguchi, Y.; Osada, K.; Uchida, K.; Kimura, H.; Yoshikawa, M.; Kudo, T.; Yasui, H.; Watanuki, M. Effects of extract of guava leaves on the development of diabetes in the db/db mouse and on the postprandial blood glucose of human subjects. Nippon Nogeikagaku Kaishi 1998, 72, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deguchi, Y. Effectiveness of consecutive ingestion and excess intake of guava leaves tea in human volunteers. J. Jpn. Council. Adv. Food Ingred. Res. 2000, 3, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Deguchi, Y.; Miyazaki, K. Anti-hyperglycemic and anti-hyperlipidemic effects of guava leaf extract. Nutr. Metab. 2010, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-de-Cerio, E.; Rodríguez-Nogales, A.; Algieri, F.; Romero, M.; Verardo, V.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Duarte, J.; Galvez, J. The hypoglycemic effects of guava leaf (Psidium guajava L.) extract are associated with improving endothelial dysfunction in mice with diet-induced obesity. Food Res. Int. 2017, 96, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Mao, D.; Li, X.; Ma, Y.; Luan, Y.; Cao, Y.; Luan, Y. Changes of intestinal microflora diversity in diarrhea model of KM mice and effects of Psidium guajava L. as the treatment agent for diarrhea. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belcaro, G.; Cornelli, U.; Luzzi, R.; Cesarone, M.R.; Dugall, M.; Feragalli, B.; Errichi, S.; Ippolito, E.; Grossi, M.G.; Hosoi, M.; et al. Pycnogenol® supplementation improves health risk factors in subjects with metabolic syndrome. Phytother. Res. 2013, 27, 1572–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, O.P. Pycnogenol® in Metabolic Syndrome and Related Disorders. Phytother. Res. 2015, 29, 949–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wei, J.; Tan, F.; Zhou, S.; Würthwein, G.; Rohdewald, P. Antidiabetic effect of Pycnogenol French maritime pine bark extract in patients with diabetes type II. Life Sci. 2004, 75, 2505–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishioka, K.; Hidaka, T.; Nakamura, S.; Umemura, T.; Jitsuiki, D.; Soga, J.; Goto, C.; Chayama, K.; Yoshizumi, M.; Higashi, Y. Pycnogenol, French maritime pine bark extract, augments endothelium-dependent vasodilation in humans. Hypertens. Res. 2007, 30, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.M.; Jeong, Y.K.; Wang, M.H.; Lee, W.Y.; Rhee, H.I. Inhibitory effect of pine extract on alpha-glucosidase activity and postprandial hyperglycemia. Nutrition 2005, 21, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, A.; Högger, P. Oligomeric procyanidins of French maritime pine bark extract (Pycnogenol) effectively inhibit alpha-glucosidase. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2007, 77, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Santos, P.; Genisheva, Z.; Botelho, C.; Santos, J.; Ramos, C.; Teixeira, J.A.; Rocha, C.M.R. Unravelling the Biological Potential of Pinus pinaster Bark Extracts. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, H.; Zhong, W.; Wang, Y.; Ikuyama, S.; Fan, B.; Gu, J. Pycnogenol® Induces Browning of White Adipose Tissue through the PKA Signaling Pathway in Apolipoprotein E-Deficient Mice. J. Diabetes Res. 2018, 2018, 9713259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, F.M.M.; Ribeiro, C.B.; Cesar, T.B.; Milenkovic, D.; Cabral, L.; Noronha, M.F.; Sivieri, K. Lemon flavonoids nutraceutical (Eriomin®) attenuates prediabetes intestinal dysbiosis: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 7283–7295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portincasa, P.; Bonfrate, L.; Vacca, M.; De Angelis, M.; Farella, I.; Lanza, E.; Khalil, M.; Wang, D.Q.; Sperandio, M.; Di Ciaula, A. Gut Microbiota and Short Chain Fatty Acids: Implications in Glucose Homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, E.; Guldas, M.; Ellergezen, P.; Acar, A.G.; Gurbuz, O. Obesity-associated pathways of anthocyanins. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 41, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapisarda, P.; Amenta, M.; Ballistreri, G.; Fabroni, S.; Timpanaro, N. Distribution, Antioxidant Capacity, Bioavailability and Biological Properties of Anthocyanin Pigments in Blood Oranges and Other Citrus Species. Molecules 2022, 27, 8675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacosa, A.; Morazzoni, P.; Bombardelli, E.; Riva, A.; Bianchi Porro, G.; Rondanelli, M. Can nausea and vomiting be treated with ginger extract? Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 19, 1291–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Walstab, J.; Krüger, D.; Stark, T.; Hofmann, T.; Demir, I.E.; Ceyhan, G.O.; Feistel, B.; Schemann, M.; Niesler, B. Ginger and its pungent constituents non-competitively inhibit activation of human recombinant and native 5-HT3 receptors of enteric neurons. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2013, 25, 439-e302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Patil, M.J.; Yu, M.; Liptak, P.; Undem, B.J.; Dong, X.; Wang, G.; Yu, S. Effects of ginger constituent 6-shogaol on gastroesophageal vagal afferent C-fibers. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2019, 31, e13585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Q.Q.; Xu, X.Y.; Cao, S.Y.; Gan, R.Y.; Corke, H.; Beta, T.; Li, H.B. Bioactive Compounds and Bioactivities of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Foods 2019, 8, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Wu, J.; Song, J.; Wen, Y. Ginger for treating nausea and vomiting: An overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 75, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Amoah, A.N.; Zhang, H.; Fu, R.; Qiu, Y.; Cao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; Lyu, Q. Effect of ginger in the treatment of nausea and vomiting compared with vitamin B6 and placebo during pregnancy: A meta-analysis. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022, 35, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongrojpaw, D.; Somprasit, C.; Chanthasenanont, A. A randomized comparison of ginger and dimenhydrinate in the treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. J. Med. Assoc. Thail. 2007, 90, 1703–1709. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.; Chen, X.; Yan, X.; He, J.; Nie, Z. The preventive and relieving effects of ginger on postoperative nausea and vomiting: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2022, 125, 104094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, K.; Choi, H.K.; Lee, S.A.; Lee, H.J. Effects of Ginger Intake on Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting: A Systematic Review of Randomized Clinical Trials. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafieipour, N.; Gharbi, N.; Rahimi, H.; Kohansal, A.; Sadeghi-Dehsahraei, H.; Fadaei, M.; Tahmasebi, M.; Momeni, S.A.; Ostovar, N.; Ahmadi, M.; et al. Ginger intervention on body weight and body composition in adults: A GRADE-assessed systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of 27 randomized controlled trials. Nutr. Rev. 2024, 82, 1651–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebrahimzadeh, A.; Ebrahimzadeh, A.; Mirghazanfari, S.M.; Hazrati, E.; Hadi, S.; Milajerdi, A. The effect of ginger supplementation on metabolic profiles in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Complement. Ther. Med. 2022, 65, 102802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maharlouei, N.; Tabrizi, R.; Lankarani, K.B.; Rezaianzadeh, A.; Akbari, M.; Kolahdooz, F.; Rahimi, M.; Keneshlou, F.; Asemi, Z. The effects of ginger intake on weight loss and metabolic profiles among overweight and obese subjects: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 1753–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.M. CODEX-aligned dietary fiber definitions help to bridge the ‘fiber gap’. Nutr. J. 2014, 13, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Jiménez, J. Dietary fiber: Still alive. Food Chem. 2024, 439, 138076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayib, M.; Larson, J.; Slavin, J. Dietary fibers reduce obesity-related disorders: Mechanisms of action. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2020, 23, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, T.M.; Kabisch, S.; Pfeiffer, A.F.H.; Weickert, M.O. The Health Benefits of Dietary Fibre. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Hu, S.; Liu, Y.; De Alwis, S.A.S.S.; Yu, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J. Dietary Fiber as Prebiotics: A Mitigation Strategy for Metabolic Diseases. Foods 2025, 14, 2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhar, M.; Zhu, Y.; Qin, L. The Interplay of Dietary Fibers and Intestinal Microbiota Affects Type 2 Diabetes by Generating Short-Chain Fatty Acids. Foods 2023, 12, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, S.; Beck, E.; Salman, H.; Tapsell, L. New Horizons for the Study of Dietary Fiber and Health: A Review. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2016, 71, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, S.; Weickert, M.O.; Pfeiffer, A.F.H. The role of cereal soluble fiber in the beneficial modulation of glycometabolic gastrointestinal hormones. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 4331–4347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wharton, S.; Davies, M.; Dicker, D.; Lingvay, I.; Mosenzon, O.; Rubino, D.M.; Pedersen, S.D. Managing the gastrointestinal side effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists in obesity: Recommendations for clinical practice. Postgrad. Med. 2022, 134, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, C.; Chen, L. Association between different GLP-1 receptor agonists and gastrointestinal adverse reactions: A real-world disproportionality study based on FDA adverse event reporting system database. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1043789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.K.; Rossi, M.; Bajka, B.; Whelan, K. Dietary fibre in gastrointestinal health and disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, K.; Saha, S.; Umar, S. Health Benefits of Dietary Fiber for the Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, M.; Tonarelli, S.; Barracca, F.; Rettura, F.; Pancetti, A.; Ceccarelli, L.; Ricchiuti, A.; Costa, F.; de Bortoli, N.; Marchi, S.; et al. Chronic Constipation: Is a Nutritional Approach Reasonable? Nutrients 2021, 13, 3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, J.; Thapa, B.R.; Kumari, R.; Puttaiah Kadyada, S.; Rana, S.; Lal, S.B. Efficacy of Oral Psyllium in Pediatric Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Double-Blind Randomized Control Trial. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2023, 76, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.; Li, Y.; He, Y.; Chen, F.; Mi, B.; Li, J.; Xie, J.; Ma, G.; Yang, J.; Xu, K.; et al. Effects of dietary fibers or probiotics on functional constipation symptoms and roles of gut microbiota: A double-blinded randomized placebo trial. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2197837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalanka, J.; Major, G.; Murray, K.; Singh, G.; Nowak, A.; Kurtz, C.; Silos-Santiago, I.; Johnston, J.M.; de Vos, W.M.; Spiller, R. The Effect of Psyllium Husk on Intestinal Microbiota in Constipated Patients and Healthy Controls. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.E.; Egan, B.M.; Woolson, R.F.; Mainous, A.G., 3rd; Al-Solaiman, Y.; Jesri, A. Effect of a high-fiber diet vs a fiber-supplemented diet on C-reactive protein level. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007, 167, 502–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Liu, W.; Yu, W.; Huang, L.; Ji, C.; Liu, X.; Lu, Z. Psyllium seed husk regulates the gut microbiota and improves mucosal barrier injury in the colon to attenuate renal injury in 5/6 nephrectomy rats. Ren. Fail. 2023, 45, 2197076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Y.W.; Gu, Y.L.; Mao, X.Q.; Zhang, L.; Pei, Y.F. Effects of probiotics on type II diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wu, L.; Qin, L.; Liu, T. The effects of probiotic administration on patients with prediabetes: A meta-analysis and systematic review. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahboubi, M. Lactobacillus gasseri as a Functional Food and Its Role in Obesity. Int. J. Med. Rev. 2019, 6, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, A.R.; Jung, D.H.; Lee, T.S.; Kim, J.K.; Lee, Y.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, S.Y.; Yoo, Y.C.; Ahn, J.H.; Hong, E.H.; et al. Lactobacillus plantarum NCHBL-004 modulates high-fat diet-induced weight gain and enhances GLP-1 production for blood glucose regulation. Nutrition 2024, 128, 112565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paddon-Jones, D.; Rasmussen, B.B. Dietary protein recommendations and the prevention of sarcopenia. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2009, 12, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giglio, B.M.; Lobo, P.C.B.; Pimentel, G.D. Effects of whey protein supplementation on adiposity, body weight, and glycemic parameters: A synthesis of evidence. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2023, 33, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willoughby, D.; Hewlings, S.; Kalman, D. Body Composition Changes in Weight Loss: Strategies and Supplementation for Maintaining Lean Body Mass, a Brief Review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoffersen, B.; Sanchez-Delgado, G.; John, L.M.; Ryan, D.H.; Raun, K.; Ravussin, E. Beyond appetite regulation: Targeting energy expenditure, fat oxidation, and lean mass preservation for sustainable weight loss. Obesity 2022, 30, 841–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeland, I.J.; Linge, J.; Birkenfeld, A.L. Changes in lean body mass with glucagon-like peptide-1-based therapies and mitigation strategies. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2024, 26 (Suppl. 4), 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikou, A.; Dermiki-Gkana, F.; Penteris, M.; Constantinides, T.K.; Kontogiorgis, C. A systematic review of the effect of semaglutide on lean mass: Insights from clinical trials. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2024, 25, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holwerda, A.M.; van Loon, L.J.C. The impact of collagen protein ingestion on musculoskeletal connective tissue remodeling: A narrative review. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 1497–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar, S. Nutritional and Functional Importance of Whey Protein in Human Health and Food Applications. Appl. Agric. Sci. 2024, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, H.K.F.; Kattah, F.M.; Piccolo, M.S.; dos Santos, E.A.; de Araújo Ventura, L.H.; Cerqueira, F.R.; Vieira, C.M.A.F.; Leite, J.I.A. The Role of Whey Protein in Maintaining Fat-Free Mass and Promoting Fat Loss After 18 Months of Bariatric Surgery. Obesities 2025, 5, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balshaw, T.G.; Funnell, M.P.; McDermott, E.; Maden-Wilkinson, T.M.; Abela, S.; Quteishat, B.; Edsey, M.; James, L.J.; Folland, J.P. The effect of specific bioactive collagen peptides on function and muscle remodeling during human resistance training. Acta Physiol. 2023, 237, e13903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirmse, M.; Oertzen-Hagemann, V.; de Marées, M.; Bloch, W.; Platen, P. Prolonged Collagen Peptide Supplementation and Resistance Exercise Training Affects Body Composition in Recreationally Active Men. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdzieblik, D.; Jendricke, P.; Oesser, S.; Gollhofer, A.; König, D. The Influence of Specific Bioactive Collagen Peptides on Body Composition and Muscle Strength in Middle-Aged, Untrained Men: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oertzen-Hagemann, V.; Kirmse, M.; Eggers, B.; Pfeiffer, K.; Marcus, K.; de Marées, M.; Platen, P. Effects of 12 Weeks of Hypertrophy Resistance Exercise Training Combined with Collagen Peptide Supplementation on the Skeletal Muscle Proteome in Recreationally Active Men. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centner, C.; Jerger, S.; Mallard, A.; Herrmann, A.; Varfolomeeva, E.; Gollhofer, S.; Oesser, S.; Sticht, C.; Gretz, N.; Aagaard, P.; et al. Supplementation of Specific Collagen Peptides Following High-Load Resistance Exercise Upregulates Gene Expression in Pathways Involved in Skeletal Muscle Signal Transduction. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Playford, R.J.; Weiser, M.J. Bovine Colostrum: Its Constituents and Uses. Nutrients 2021, 13, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, I.; Dhanawat, M.; Sharma, M.; Gupta, S. Exploring the Potential Benefits of Bovine Colostrum Supplementation in the Management of Diabetes and its Complications: A Comprehensive Review. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2024, 21, e200224227161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Playford, R.J. Effects of Chicken Egg Powder, Bovine Colostrum, and Combination Therapy for the Treatment of Gastrointestinal Disorders. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalçıntaş, Y.M.; Duman, H.; López, J.M.M.; Portocarrero, A.C.M.; Lombardo, M.; Khallouki, F.; Koch, W.; Bordiga, M.; El-Seedi, H.; Raposo, A.; et al. Revealing the Potency of Growth Factors in Bovine Colostrum. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, K.; Abo-Elela, M.G.M.; El-Baseer, K.A.A.; Ahmed, A.E.; Ahmad, F.A.; Tawfeek, M.S.K.; El-Houfey, A.A.; Aboul Khair, M.D.; Abdel-Salam, A.M.; Abo-Elgheit, A.; et al. Effects of bovine colostrum on recurrent respiratory tract infections and diarrhea in children. Medicine 2016, 95, e4560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, S.H.; Meheissen, M.A.; Omar, O.M.; Elbana, D.A. Bovine Colostrum in the Treatment of Acute Diarrhea in Children: A Double-Blinded Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2020, 66, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, A.K.; Mahalanabis, D.; Ashraf, H.; Unicomb, L.; Eeckels, R.; Tzipori, S. Hyperimmune cow colostrum reduces diarrhoea due to rotavirus: A double-blind, controlled clinical trial. Acta Paediatr. 1995, 84, 996–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, Y.W.; Jiang, J.J.; Song, Q.K. Bovine colostrum and product intervention associated with relief of childhood infectious diarrhea. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.; Rana, R. Pedimune in recurrent respiratory infection and diarrhoea—The Indian experience—The pride study. Indian J. Pediatr. 2006, 73, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgeon, J.P.; Mutasa, K.; Bwakura-Dangarembizi, M.; Amadi, B.; Ngosa, D.; Dzikiti, A.; Chandwe, K.; Besa, E.; Mutasa, B.; Murch, S.H.; et al. Therapeutic interventions targeting enteropathy in severe acute malnutrition modulate systemic and vascular inflammation and epithelial regeneration. EBioMedicine 2025, 111, 105478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslamian, G.; Ardehali, S.H.; Baghestani, A.R.; Vahdat Shariatpanahi, Z. Effects of early enteral bovine colostrum supplementation on intestinal permeability in critically ill patients: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Nutrition 2019, 60, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Kruszewski, A.; Brautigan, D.L. Cellular chromium enhances activation of insulin receptor kinase. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 8167–8175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Hulst, R.R.; van Kreel, B.K.; von Meyenfeldt, M.F.; Brummer, R.J.; Arends, J.W.; Deutz, N.E.; Soeters, P.B. Glutamine and the preservation of gut integrity. Lancet 1993, 341, 1363–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, S.; Sato, T.; Fujita, H.; Kawatani, M.; Yamada, Y. Effects of GLP-1 receptor agonist on changes in the gut bacterium and the underlying mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiles, L.I.; Ferrao, K.; Mehta, K.J. Role of zinc in health and disease. Clin. Exp. Med. 2024, 24, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Yu, P.; Chan, W.N.; Xie, F.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, L.; Leung, K.T.; Lo, K.W.; Yu, J.; Tse, G.M.K.; et al. Cellular zinc metabolism and zinc signaling: From biological functions to diseases and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayawardena, R.; Ranasinghe, P.; Galappatthy, P.; Malkanthi, R.; Constantine, G.; Katulanda, P. Effects of zinc supplementation on diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2012, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyoshi, Y.; Tanabe, S.; Suzuki, T. Cellular zinc is required for intestinal epithelial barrier maintenance via the regulation of claudin-3 and occludin expression. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2016, 311, G105–G116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Valenzano, M.C.; Mercado, J.M.; Zurbach, E.P.; Mullin, J.M. Zinc supplementation modifies tight junctions and alters barrier function of CACO-2 human intestinal epithelial layers. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2013, 58, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullin, J.M.; Skrovanek, S.M.; Valenzano, M.C. Modification of tight junction structure and permeability by nutritional means. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1165, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efthymakis, K.; Neri, M. The role of Zinc L-Carnosine in the prevention and treatment of gastrointestinal mucosal disease in humans: A review. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2022, 46, 101954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnasari, P.W.; Nasihun, T.; Zulaikhah, S.T. Effects of Single or Combined Supplementation of Probiotics and Zinc on Histological Features of Ileum, Glucagon Like Peptide-1 and Ghrelin Levels in Malnourished Rats. Folia Medica 2021, 63, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, B.; Kapoor, D.; Gautam, S.; Singh, R.; Bhardwaj, S. Dietary Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs): Uses and Potential Health Benefits. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2021, 10, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, D.; Lavie, C.J.; Elagizi, A.; Milani, R.V. Update on Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on Cardiovascular Health. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anissa, L.; Lestari, W. Effect of omega− 3 fatty acdid supplementation on reduce body weight and body fat mass in obesity. World Nutr. J. 2025, 8, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liao, X.; Elbelt, U.; Weylandt, K.H. The effects of omega-3 fatty acids in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2022, 182, 102456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, N.; Shen, Y.; Li, B.; Chen, B.E.; Li, X. Association Between Omega-3 Fatty Acid Intake and Dyslipidemia: A Continuous Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e029512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santo André, H.C.; Esteves, G.P.; Barreto, G.H.C.; Longhini, F.; Dolan, E.; Benatti, F.B. The Influence of n-3PUFA Supplementation on Muscle Strength, Mass, and Function: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2023, 14, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, Y.; Tsuji, K.; Ochi, E. Effects of Omega-3 fatty acids supplementation and resistance training on skeletal muscle. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2024, 61, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursoniu, S.; Sahebkar, A.; Serban, M.-C.; Antal, D.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Cicero, A.; Athyros, V.; Rizzo, M.; Rysz, J.; Banach, M.; et al. Lipid-modifying effects of krill oil in humans: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andraka, J.M.; Sharma, N.; Marchalant, Y. Can krill oil be of use for counteracting neuroinflammatory processes induced by high fat diet and aging? Neurosci. Res. 2020, 157, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tou, J.C.; Jaczynski, J.; Chen, Y.C. Krill for human consumption: Nutritional value and potential health benefits. Nutr. Rev. 2007, 65, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berge, R.K.; Ramsvik, M.S.; Bohov, P.; Svardal, A.; Nordrehaug, J.E.; Rostrup, E.; Bruheim, I.; Bjørndal, B. Krill oil reduces plasma triacylglycerol level and improves related lipoprotein particle concentration, fatty acid composition and redox status in healthy young adults—A pilot study. Lipids Health Dis. 2015, 14, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtson Nash, S.M.; Schlabach, M.; Nichols, P.D. A nutritional-toxicological assessment of Antarctic krill oil versus fish oil dietary supplements. Nutrients 2014, 6, 3382–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]