2. Materials and Methods

A total of 88 individuals (25 men and 63 women) were examined. The mean age of the participants was 37.42 ± 11.77 years. As is well known, while obesity is strongly linked to metabolic complications, some obese individuals remain metabolically healthy, and some non-obese individuals exhibit metabolic issues, giving rise to the concept of different metabolic phenotypes across body mass index (BMI) categories [

3,

9]. That is why our participants were stratified into four obesity phenotypes based on their anthropometric and metabolic parameters, including waist circumference (WC), visceral fat percentage (VF%), BMI.

The classification criteria were as follows:

Phenotype I (Ph-I)—MHO with normal body weight (BW).

Phenotype II (Ph-II)—MUO with normal BW.

Phenotype III (Ph-III)—MHO with elevated BW (BMI > 30 kg/m2).

Phenotype IV (Ph-IV)—MUO with elevated BW (BMI > 30 kg/m2).

Metabolic syndrome was defined based on the criteria outlined in the Joint Interim Statement as follows: (1) triglyceride levels ≥ 150 mg/dL or the use of lipid-lowering medications; (2) systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 85 mmHg, or the use of antihypertensive medications; (3) fasting plasma glucose (FPG) ≥ 100 mg/dL or treatment for diabetes; and (4) high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels < 40 mg/dL for men and <50 mg/dL for women [

10].

Group Characteristics

Ph-I included 23 participants (5 men, aged 37.18 ± 7.19 years; 18 women, aged 34.21 ± 4.89 years). The mean age for this group was used (30.78 ± 10.19 years). Ph-II comprised 21 participants (6 men, aged 38.91 ± 6.77 years; 15 women, aged 36.18 ± 12.31 years). The mean age of this group was 35.19 ± 15.74 years. Ph-III consisted of 22 participants (8 men, aged 33.77 ± 9.11 years; 14 women, aged 37.49 ± 10.24 years; p ≥ 0.05). The mean age was 34.59 ± 10.11 years. Ph-IV included 22 participants (6 men, aged 43.52 ± 12.88 years; 16 women, aged 39.92 ± 6.56 years; p ≥ 0.05). The mean age was 37.42 ± 11.77 years. Across all phenotypes, there were no statistically significant differences in age distribution between males and females (p ≥ 0.05), allowing for the use of group mean values in further analyses.

2.1. Anthropometric and Clinical Characteristics

Height was measured without shoes using a stadiometer (SECA-222, Hamburg, Germany). BW was determined in the morning, with participants wearing light clothing and no outer garments, using medical scales (VEM-150M, Kyiv, Ukraine). WC was measured in centimeters using a professional measuring tape (GulieK II, Gays Mills, WI, USA) at the midpoint between the lower margin of the last rib and the upper border of the iliac crest.

A normal BW was defined as a BMI of 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, overweight as 25.0–29.9 kg/m2, obesity class I as 30.0–34.9 kg/m2, obesity class II as 35.0–39.9 kg/m2, and obesity class III as ≥40.0 kg/m2.

Comprehensive clinical anamnesis was obtained for each patient to identify cardiovascular risk factors, followed by an assessment of the 10-year CVD risk using two validated online risk calculators: SCORE2 and QRISK3 [

11,

12].

During the evaluation of anthropometric parameters, it was established that all participants in the clinical group exhibited WC exceeding the commonly accepted normative values. According to current scientific evidence, an increased WC is a reliable indicator of visceral obesity, which is recognized as a key risk factor for the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Under such conditions, the core mechanisms of metabolic dysregulation—particularly insulin resistance—are activated, ultimately leading to impairments in carbohydrate metabolism.

The clinical study included the following procedures: BP measurement was performed in accordance with the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines [

13]. BP was measured on the brachial artery using a sphygmomanometer (AND Medical, model UA-888, A&D Company Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) twice, at a five-minute interval, with participants in a seated position. The average value of the two readings was recorded. All patients underwent cardiac and pulmonary auscultation, as well as palpation of the liver and kidneys. A standard 12-lead ECG was recorded using a “UKARD” electrocardiograph (Bratislava, Slovakia) following established clinical protocols.

The carbohydrate metabolism was assessed based on the levels of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), results from the oral glucose tolerance test: fasting glucose (mmol/L), and postprandial glucose levels two hours after a 75 g glucose load. Blood samples were taken from the participants in a fasting state at 8:00 AM, after a 10-h fasting period. Glucose concentration was measured in venous blood plasma using an amperometric method on a Biosen C-Line biochemical analyzer, manufactured by EKF Diagnostic (Barleben, Germany). The reference range for glucose is 3.3–5.5 mmol/L.

The level of HbA1c was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography on a D10 analyzer, manufactured by Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France, with normative values for this marker being <6%.

Lipid fraction concentrations in the serum of patients were evaluated using a photometric method on the AU-480 biochemical analyzer (“Beckman Coulter, Inc.,” Brea, CA, USA).

The levels of total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) were determined. The reference values are provided according to the data from the certified laboratory VOKVEC, which performed the analysis: TC, normal values < 5.2 mmol/L; TG, normal value < 1.72 mmol/L; LDL-C, average normal level < 3 mmol/L; HDL-C, normal value ≥ 1.2 mmol/L.

Additionally, in the examined patients, the triglyceride–glucose index (TGI) was calculated as follows: TGI = (TG mmol/L × Glucose mmol/L)/2, which was associated with the insulin resistance index, with a normal value ≤ 3.0.

The atherogenic index (AI) was calculated using the formula: AI = (TC − HDL-C)/HDL-C, with normal values AI ≤ 3.0.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria encompassed individuals classified as being at risk for T2DM, specifically those presenting with an excessive WC indicative of visceral fat (VF) accumulation, a primary hallmark of insulin resistance.

Exclusion criteria included: established diagnosis of T2DM; hypercortisolism; ongoing therapy with glucagon-like peptide-1 analogs, glucocorticoids, or oral hypoglycemic agents; insulin therapy; history of cerebrovascular accidents; chronic cardiovascular diseases; presence of active inflammatory processes; severe hepatic or biliary disorders; chronic kidney disease; and pregnancy.

All participants underwent comprehensive clinical and laboratory examination at the Vinnytsia Regional Clinical Highly Specialized Endocrinology Center. All study subjects provided informed consent prior to inclusion, after receiving detailed information about the study protocol, which complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committee, and each participant signed the document ‘Informed Voluntary Consent for Diagnostic Procedures, Treatment, and Participation in Research’ in accordance with Order No. 110 of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine (14 February 2012), developed in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

The statistical analysis was performed using the licensed software package Statistica 7 (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA) with nonparametric analytical methods. Additional calculations were carried out using OpenEpi (version 3) and the open-source Diagnostic Test calculator. Quantitative data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (M ± SD), and results were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. Correlation analysis was performed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, while linear univariate and multivariate regression models were applied to evaluate associations. The data were assessed for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, and ANOVA was employed to determine the influence of qualitative factors. The strength of correlation was interpreted as high (0.5 ≤ r ≤ 1.0), moderate (0.3 ≤ r ≤ 0.5), low (0.1 ≤ r ≤ 0.3), or negligible (0.0 ≤ r ≤ 0.09).

3. Results

Comparative analysis of anthropometric data revealed progressive differences across phenotypes in VF% and BMI. Patients in Ph-I and Ph-II demonstrated normal BMI values (<30 kg/m

2), whereas Ph-III and Ph-IV exhibited elevated BMI consistent with obesity (

Table 1). Moreover, Ph-II and Ph-IV presented clear metabolic abnormalities, including early signs of dyslipidemia and glucose metabolism disturbances.

Patients in group Ph-I had a BMI of 24.37 ± 2.42 kg/m

2, which confirms the absence of obesity in this group. However, their WC and levels of VF and fat mass according to bioimpedance analysis were higher than the reference values, which may indicate early manifestations of insulin resistance. The waist-to-height ratio was calculated for patients in group Ph-I, which confirms the presence of visceral obesity in the examined group despite a normal BMI, since the waist-to-height ratio was close to the upper reference limit in women and exceeded the normative value in men (

Table 2). Systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP) values in these patients were within the reference range. In patients of group Ph-II, metabolic disturbances were noted, which can be explained by an increase in WC (as a manifestation of insulin resistance in both men and women) and by the accumulation of VF, which significantly differed from the reference values (

p ≤ 0.05). The waist-to-height ratio exceeded the reference norms in Ph-II patients regardless of sex. In 16 patients (76%) of this group, elevated blood pressure was observed (SBP—145.51 ± 15.05 mmHg, DBP—85.07 ± 8.42 mmHg). These values were significantly higher compared with group Ph-I (

p ≤ 0.05). However, in patients of group Ph-III, even in the presence of obesity (BMI—38.81 ± 8.07 kg/m

2), which significantly differed from the BMI of Ph-II and Ph-I patients (

p ≤ 0.05), the WC and waist-to-height ratio exceeded the reference norms, confirming progression of visceral obesity in this group. SBP (115.90 ± 4.53 mmHg) and DBP (73.40 ± 5.43 mmHg) remained within normal limits, indicating the presence of MHO despite significantly higher WC (115.92 ± 16.65 cm) compared with Ph-I (

p ≤ 0.05) and higher VF levels (19.40 ± 5.87%) compared with Ph-I and Ph-II (

p ≤ 0.05). In patients of group Ph-IV, MUO was confirmed. BMI in this group was 33.09 ± 2.07 kg/m

2, which significantly differed from that of groups Ph-I, Ph-II, and Ph-III (

p ≤ 0.05). VF level, WC, and waist-to-height ratio significantly exceeded the reference values and the results of groups Ph-I, Ph-II, and Ph-III (

p ≤ 0.05). SBP (136.09 ± 10.69 mmHg) and DBP (82.52 ± 6.31 mmHg) confirmed arterial hypertension. The obtained results demonstrate the importance of timely determining which clinical group a patient belongs to according to obesity phenotype in order to prevent future risks of metabolic disorders and to diagnose cardiovascular system changes.

Analysis of carbohydrate metabolism parameters according to obesity phenotypes showed that patients in group Ph-I had no disturbances of carbohydrate metabolism; fasting glucose, postprandial glucose, and HbA1c levels did not exceed the reference values (

Table 3). In contrast, patients in group Ph-II, even with normal BW, were diagnosed with a prediabetic state, as fasting glucose (5.71 ± 0.14 mmol/L), postprandial glucose (7.70 ± 0.47 mmol/L), and HbA1c (5.72 ± 0.10%) were significantly higher than in Ph-I (

p ≤ 0.05). It is noteworthy that in patients of group Ph-III, despite confirmed obesity (BMI—38.81 ± 8.07 kg/m

2), no abnormalities in carbohydrate metabolism were observed. Fasting glucose, postprandial glucose, and HbA1c values remained within the reference range and were significantly lower compared with Ph-II (

p ≤ 0.05). In patients of group Ph-IV, carbohydrate metabolism disturbances were identified in the presence of obesity (BMI—33.09 ± 2.07 kg/m

2). The carbohydrate metabolism parameters in Ph-IV were significantly higher compared with those of groups Ph-III and Ph-I (

p ≤ 0.05).

During the analysis of the relationship between BMI and HbA1c levels, it was found that the strength of the correlation (r) in patients with Ph-I was 0.27, whereas in Ph-IV it reached 0.57. The analysis demonstrated that with increasing BW, the linear dependence between BMI and HbA1c becomes stronger. The point-prediction model confirmed a trend of rising HbA1c levels with increasing BMI, with this relationship being most pronounced in patients with Ph-IV. When examining the relationship between BMI and fasting glucose levels in patients with phenotypes I, II, and IV, a low correlation strength was observed. At the same time, in patients with visceral obesity (Ph-III), this indicator was higher, with a correlation coefficient of r = 0.32. This indicates an association between increasing BMI and elevated fasting glucose levels, which is most evident in patients with visceral type obesity. Analysis of the relationship between postprandial glycemia and BMI in patients with different obesity phenotypes did not reveal a significant correlation (

Table 4). At the same time, in patients with Ph IV, a weak but statistically significant correlation (r = 0.25) was identified, which exceeded the corresponding values observed in groups Ph-I, Ph-II, and Ph-III (

p ≤ 0.05). Thus, HbA1c may serve as a valuable marker for assessing carbohydrate metabolism disorders in patients with different forms of obesity, particularly in the presence of VF.

When examining the relationship between WC and HbA1c levels in patients with different obesity phenotypes, it was found that the strength of the correlation increased with the progression of visceral obesity. In patients with Ph-I, the correlation coefficient was r = 0.30, whereas in Ph-III it reached r = 0.56, and in Ph-IV—r = 0.42 (

Table 4). This indicates that an increase in WC is accompanied by an elevation in HbA1c levels regardless of obesity phenotype. When analyzing the relationship between fasting glucose and WC across obesity types, the highest correlation was observed in patients with Ph-II (metabolically unhealthy overweight), r = 0.40. This value significantly exceeded the corresponding indicators in groups Ph-I, Ph-III, and Ph-IV (

p ≤ 0.05). Analysis of the relationship between postprandial glycemia and WC did not reveal statistically significant correlations.

Investigation of the impact of VF% on carbohydrate metabolism indicators demonstrated that with increasing VF content, the correlation with HbA1c strengthened—from moderate to strong depending on VF levels (

Table 4). A significant correlation was also observed between fasting glucose and VF, especially in patients with Ph-III, where the correlation coefficient reached r = 0.61. Regression and ANOVA analyses confirmed this observation, with a multiple correlation coefficient of R = 0.61. In patients with Ph IV, a strong correlation between VF and fasting glycemia was also identified (r = 0.54), confirming literature reports suggesting that VF has a greater impact on carbohydrate metabolism than BMI or WC. Additionally, a significantly strong positive correlation was recorded between VF and postprandial glycemia (r = 0.55), statistically higher than in groups Ph-I, Ph-II, and Ph-III (

p ≤ 0.05).

Overall, fasting glycemia appears to be the most sensitive indicator with the strongest relationship to VF content, whereas the correlation between VF and HbA1c is moderate to high.

It is well known that the presence and degree of general and visceral obesity in patients are closely associated with dyslipidemia and CVD risk [

14]. Changes in the lipid profile of the blood serum can predict the development and progression of atherogenesis. In patients of Ph-I, no significant differences in lipid profile indicators were found compared to reference values, confirming the data from literature about MHO with normal weight, regardless of gender. In the clinical group of Ph-II, total cholesterol (5.99 ± 0.61 mmol/L), TG (1.93 ± 0.21 mmol/L), LDL-C (3.88 ± 0.51 mmol/L), and the AI (3.96 ± 0.68) exceeded the reference values and significantly differed from the results of Ph-I (

p ≤ 0.05). In patients of Ph-III, lipid profile indicators remained within the reference range and were significantly lower compared to the Ph-I group (

p ≤ 0.05). The lipid metabolism results for patients of Ph-IV with confirmed obesity (BMI 33.09 ± 2.07 kg/m

2) were expected and supported the data in the literature about MUO, as all lipid fractions were significantly higher compared to patients in the clinical groups Ph-I and Ph-III (

p ≤ 0.05) (

Table 5).

Studying the relationships between BMI and lipid metabolism indicators, it was found that the strength of the correlation (r) for cholesterol levels was as follows: in Ph-I, r = 0.18; in Ph-III, r = 0.78; and in Ph-IV, r = 0.58 (

Table 6).

Thus, as visceral obesity progresses, cholesterol levels increase. The highest correlation strength was recorded in patients with progressive obesity (III and IV) and significantly differed from the results of patients with Ph-I (

p ≤ 0.05). Notably, the highest correlation between cholesterol levels and BMI was found in Ph-III patients, despite the presence of metabolically healthy obesity in these individuals. Comparing correlation strengths between phenotypes III and IV versus II showed no statistically significant difference (

p ≤ 0.05). No significant correlation was found between WC and lipid parameters across phenotypes. The highest correlation between total cholesterol and WC was in Ph-IV (r = 0.24). Regression and ANOVA analyses confirmed statistical adequacy (

p = 0.026). The strongest associations were observed between total cholesterol and visceral fat in Ph-V (r = 0.56). HDL-C showed marked inverse relationships with visceral fat in phenotypes III and IV, with correlation coefficients of −0.62 and −0.83, respectively (

Table 6).

When assessing the correlation strength between LDL-C, the AI, TGs, and VF in patients of all obesity phenotypes, no correlation was observed, except in patients with Ph-III. Examining the correlation strength between HDL-C and VF revealed a negative inverse correlation, the strength of which increased with the progression of visceral obesity. The highest inverse relationship was observed in patients with Ph-IV (r = −0.83).

Based on the results of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, the task was set to analyze the presence and/or progression of insulin resistance using the TGI. The TGI is a marker for detecting insulin resistance and a prognostic test for cardiovascular risk in patients with excess BW [

15]. TGI exceeded the reference range in patients of all obesity phenotypes, confirming the presence of insulin resistance in the studied patients. In patients of Ph-I, TGI exceeded the upper reference limits, indicating existing insulin resistance in this group. In Ph-II, TGI progressively increased, with a statistically significant difference compared to Ph-I (

p ≤ 0.05). In patients of Ph-III, despite metabolically healthy obesity, insulin resistance was also confirmed, but the index was lower compared to Ph-II, with no significant difference (

p ≥ 0.05). In patients of Ph-IV, TGI significantly exceeded the upper limit of the reference range and significantly differed compared to results in patients of Ph-I, II, and III (

p ≤ 0.05) (

Table 7).

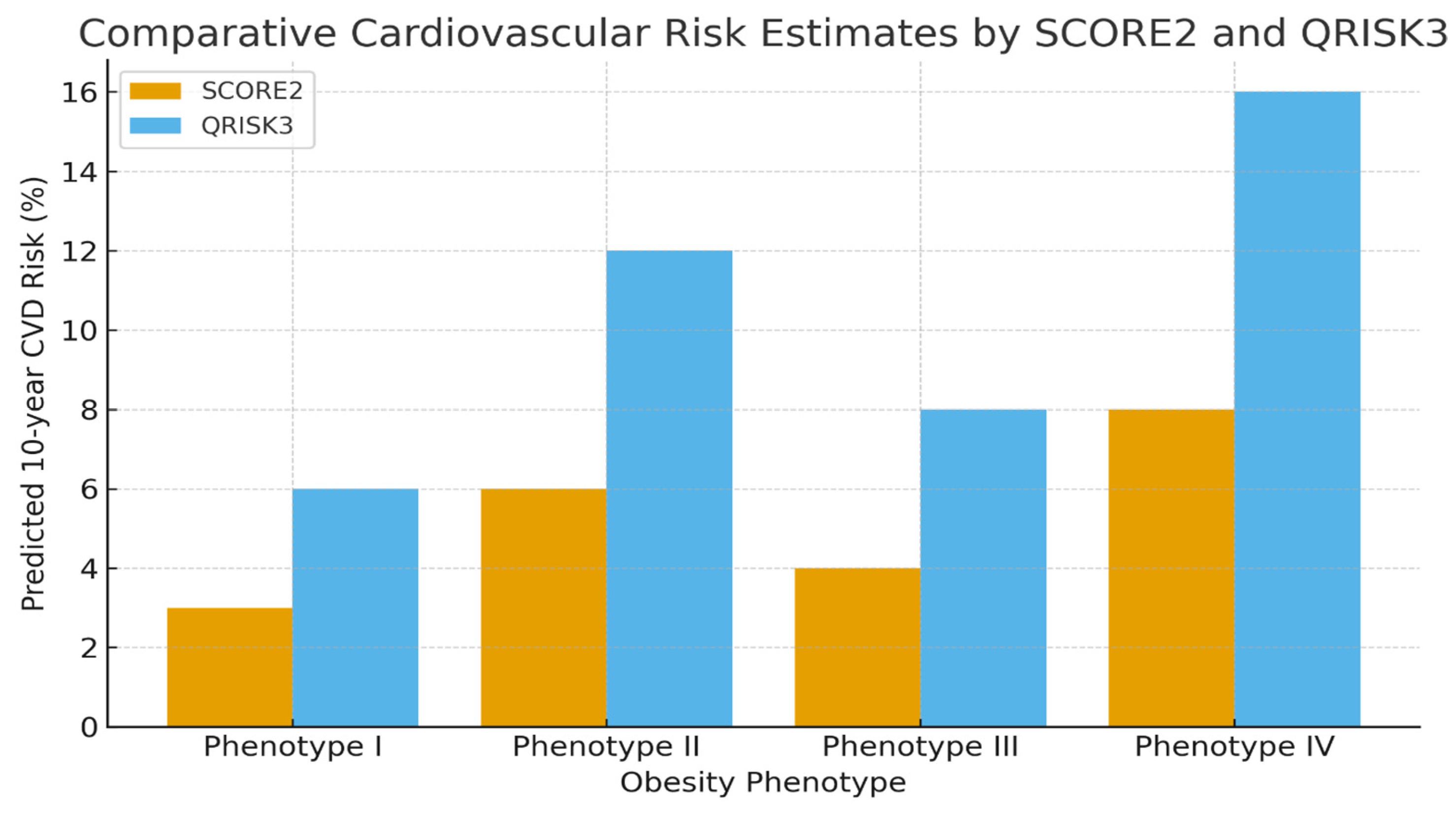

Constructive evaluation demonstrated that QRISK3 provided greater prognostic value, particularly due to its inclusion of anthropometric measures that were shown to amplify the long-term CVD risk in patients with obesity through progression of insulin resistance. According to SCORE2 estimates (which excluded body composition data), the 10-year CVD risk was 3% for Ph-I, 6% for Ph- II, 4% for Ph-III, and 8% for Ph-IV, indicating a relatively low risk among metabolically healthy obese individuals. Therefore, patients with MHO phenotype had low cardiovascular event risks. However, QRISK3 results revealed higher predicted risks across all obesity phenotypes, even in those deemed metabolically healthy, underscoring the potential for CVD progression despite normal metabolic profiles.

Based on the results of the QRISK3 questionnaire, which include anthropometric data, the following cardiovascular risk ratios for the next 10 years were obtained: risk for group I—6%, group II—12%, group III—8%, and group IV—16%. When analyzing the results from the QRISK-3 questionnaire, even for MHO phenotypes, the risks doubled, which may trigger the progression of cardiovascular complications. Our analysis of both calculators revealed an increased cardiovascular risk ratio in the II and IV groups, where metabolic disturbances were present (

Figure 1).

Further ECG-based evaluation of cardiac function revealed no rhythm or conduction disturbances in Ph-I. In Ph-II, LVH and elevated BP were frequently observed, while Ph-III showed occasional incomplete right bundle branch block (RBBB). In Ph-IV, LVH was confirmed in most patients, with consistent arterial hypertension (

Table 8). The duration of hypertension increased with metabolic impairment—averaging 4.8 years in Ph-II and over 6 years in MUO (Ph-V)—highlighting a direct association between obesity phenotypes, metabolic dysfunction, and cardiovascular burden.

4. Discussion

The need for more nuanced and multifactorial risk calculators in clinical practice is becoming increasingly apparent, especially as we recognize the complex relationship between metabolic health, obesity, and cardiovascular outcomes. Our findings are consistent with prior evidence that obesity is a major, independent contributor to cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, even in the absence of traditional risk factors [

1]. The results of our study highlight the complex interplay between obesity phenotypes, VF accumulation, and metabolic disturbances. In patients of Ph-II, metabolic dysfunctions were evident despite normal BMI, which was primarily driven by increased WC and VF accumulation. This aligns with literature demonstrating that central obesity and VF are strong predictors of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk, independent of BMI [

14]. Patients with Ph-III exhibited significant visceral obesity (high WC and VF%) despite maintained normal metabolic parameters, including normal fasting glucose, postprandial glucose, and lipid profile. This phenotype reflects MHO with VF predominance, supporting the notion that obesity alone does not invariably result in metabolic derangements. Ph-IV patients demonstrated MUO with increased VF, central adiposity, and impaired carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Notably, the TGI was markedly elevated in this group, confirming significant insulin resistance. In the context of metabolic and anthropometric research, several lifestyle and socioeconomic factors are known to influence obesity-related outcomes. Evidence from Shaikh et al. demonstrates that socioeconomic status, smoking behavior, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and dietary patterns have substantial effects on BMI and obesity risk in the U.S. population, acting as important mediators of cardiometabolic health [

16]. Individuals with lower socioeconomic status tend to exhibit higher BMI and obesity prevalence, partly due to reduced access to health-promoting resources, differences in dietary quality, and lower levels of physical activity. Similarly, the FINRISK study demonstrated a robust association between smoking status and abdominal obesity, particularly among individuals with excess body weight, highlighting smoking as both a confounder and modifier of obesity-related metabolic alterations [

17]. In addition to socioeconomic and behavioral factors, medication use represents an important determinant of cardiometabolic risk profiles. For example, findings from a community-based evaluation of cardiovascular risk using the QRISK

®3 algorithm in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus in India highlight that the inclusion of variables such as antihypertensive treatment, statin therapy, and other long-term medications can meaningfully alter estimated cardiovascular risk [

18].

Cardiovascular risk assessment using QRISK3 revealed substantially higher predicted 10-year risks compared to SCORE2 estimates, highlighting the additive prognostic value of including anthropometric and metabolic data in risk calculators. Correlation analyses revealed that HbA1c and fasting glucose levels were most strongly associated with VF content, particularly in Ph-III and Ph-IV patients. While BMI correlated moderately with lipid parameters, VF showed stronger and more specific associations, particularly with HDL-C, which exhibited a negative correlation that intensified with progression of visceral obesity (r = −0.83 in Ph-IV). These findings underscore the critical role of VF as a determinant of both carbohydrate and lipid metabolic dysfunctions, often exceeding the predictive value of BMI or WC alone.

The data also suggest that MHO phenotypes, despite preserved carbohydrate and lipid profiles, are not entirely devoid of cardiometabolic risk. Early insulin resistance (as indicated by elevated TGI) may precede overt metabolic abnormalities. In contrast, MUO phenotypes (Ph-II and Ph-IV) consistently exhibited disturbances across multiple metabolic domains, with a clear relationship to VF accumulation and central adiposity.

Recent large-scale epidemiological studies have shown that adiposity, particularly VF accumulation, induces low-grade systemic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and sympathetic overactivation—processes that collectively accelerate atherosclerosis and cardiac remodeling [

2]. The SCORE2 algorithm, though robust for population-level risk prediction in Europe [

6], omits anthropometric data such as BMI and WC.

The present study found that individuals with MUO had higher systolic and diastolic blood pressures, increased LVH prevalence, and a longer duration of hypertension than metabolically healthy groups. These findings corroborate earlier cohort data indicating that MUO phenotypes are associated with a markedly increased incidence of cardiovascular and renal complications [

3]. The Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study demonstrated that metabolically unhealthy obesity predicted the future development of cardio-renal-metabolic multimorbidity over two decades, even after adjusting for conventional risk factors [

3]. Similarly, our results suggest that metabolic abnormalities accelerate vascular remodeling and cardiac hypertrophy, supporting the hypothesis that metabolic dysfunction amplifies the hemodynamic effects of adiposity. Our study also revealed that BP levels were significantly elevated in phenotypes II and IV, where metabolic disturbances were most prominent. These findings align with the 2024 ESC Guidelines on Hypertension, which emphasize early identification and management of BP elevations in high-risk groups, including those with obesity and insulin resistance [

13]. The co-existence of hypertension and LVH in MUO patients highlights the cumulative cardiovascular burden imposed by the interaction of mechanical (hemodynamic load) and metabolic (insulin resistance, inflammation) stressors.

Importantly, even participants classified as MHO showed subtle ECG abnormalities, such as evidence of LVH and incomplete RBBB, and an approximately twofold increase in predicted cardiovascular risk by QRISK3 suggesting that structural cardiac remodeling may occur before overt metabolic derangements become clinically evident. This aligns with evidence suggesting that MHO represents a transient or unstable phenotype, with many individuals eventually developing metabolic syndrome or insulin resistance [

4,

5]. The underlying mechanisms may involve adipocyte hypertrophy, ectopic lipid accumulation, and subclinical inflammation, which promote endothelial dysfunction before overt biochemical abnormalities are detectable. These early subclinical changes emphasize the need for proactive monitoring and lifestyle intervention, even among apparently metabolically healthy obese patients.

When comparing our findings to those of Preda et al. (2023), who highlighted the role of visceral adiposity and chronic inflammation in cardiovascular risk, it becomes evident that anthropometric parameters remain indispensable for accurate risk stratification [

2]. The inclusion of WC and BMI in QRISK3 provides a more comprehensive reflection of these risk pathways [

19]. Moreover, Hippisley-Cox et al. (2024) demonstrated that QRISK3 outperforms earlier algorithms, particularly among women and individuals with obesity or autoimmune diseases—consistent with our observation that QRISK3 yielded higher sensitivity in detecting high-risk individuals [

7].

These findings further suggest that QRISK-3, by considering a more comprehensive set of variables, provides a more accurate and predictive risk assessment, particularly for individuals with obesity and metabolic health concerns. In contrast, the SCORE-2 calculator’s limited scope, which excludes these critical anthropometric factors, may fail to capture the elevated risk seen in certain at-risk groups. Thus, our study supports the idea that QRISK-3 is a more reliable tool for predicting cardiovascular risks in patients with metabolic disturbances, as it accounts for factors that are pivotal in understanding the full scope of cardiovascular threat.

From a clinical standpoint, these findings emphasize the pressing need to revise traditional obesity assessment protocols by integrating obesity-specific measures into standard cardiovascular risk evaluations. The reliance on algorithms such as SCORE2 alone may lead to risk underestimation, potentially delaying preventive strategies in high-risk obese patients. A combined approach—integrating anthropometric, metabolic, and functional cardiovascular markers—may provide a more accurate representation of individual risk, in line with recent recommendations for personalized prevention strategies [

1].

Thus, the integration of anthropometric data into QRISK3 could offer a more comprehensive approach to cardiovascular risk stratification, especially for patients with diverse obesity phenotypes, leading to more personalized and effective prevention strategies.

Clinical Implications and Future Directions

From a clinical perspective, these findings highlight the need to revise conventional obesity assessment protocols. Algorithms such as SCORE2, which rely primarily on metabolic and hemodynamic factors, may underestimate cardiovascular risk in patients with visceral obesity.

Our data support the clinical advantage of QRISK3 over SCORE2 in detecting cardiovascular risk among individuals with obesity. The presence of LVH and hypertension in metabolically unhealthy Phenotypes underscores the synergistic effect of metabolic dysfunction and obesity on cardiovascular outcomes. To optimize cardiovascular prevention in individuals with obesity, future research should aim to integrate a broader range of factors into risk prediction models. These could include not only anthropometric indices such as WC and BMI but also advanced imaging biomarkers and molecular profiles, offering a more comprehensive and personalized approach to cardiovascular risk assessment.