Copper-Enhanced Gold Nanoparticle Sensor for Colorimetric Histamine Detection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Colorimetric Detection of Histamine

2.3. pH and Cation Effect

2.4. Selectivity Test

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

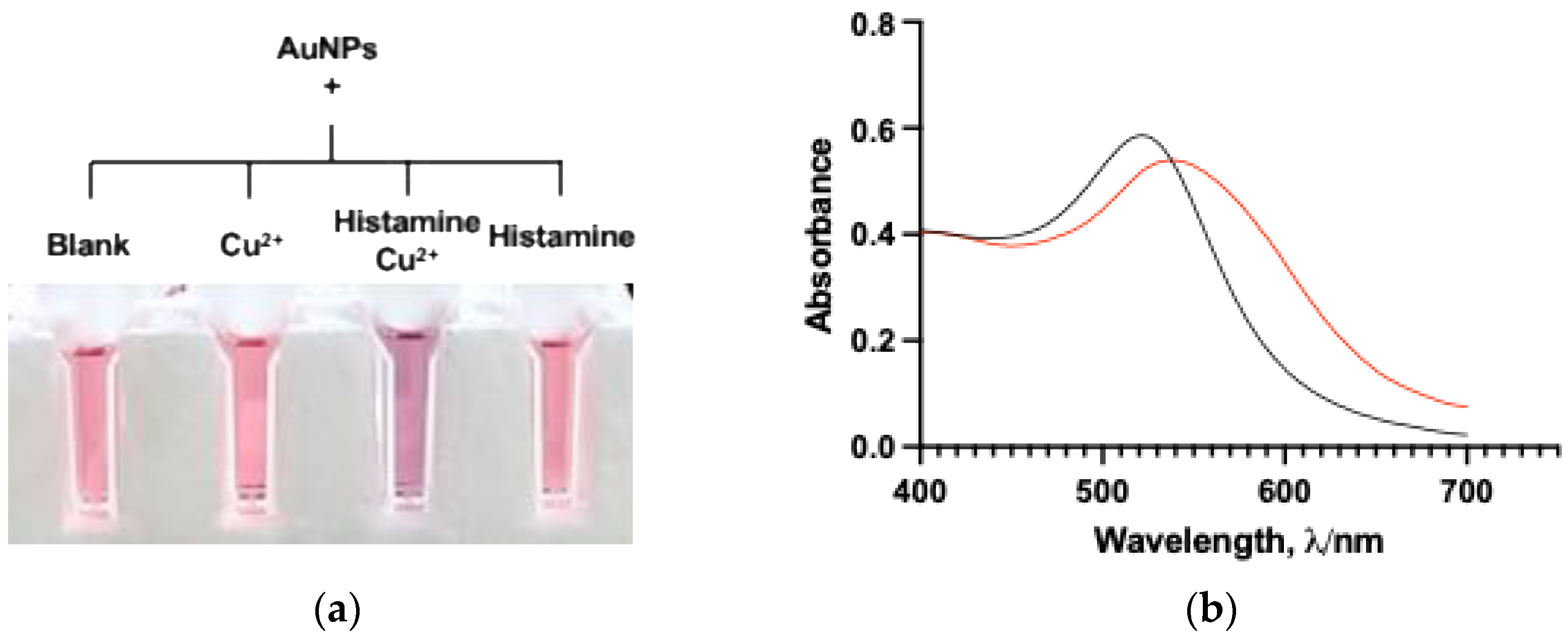

3.1. Evaluation of Basic Mechanism

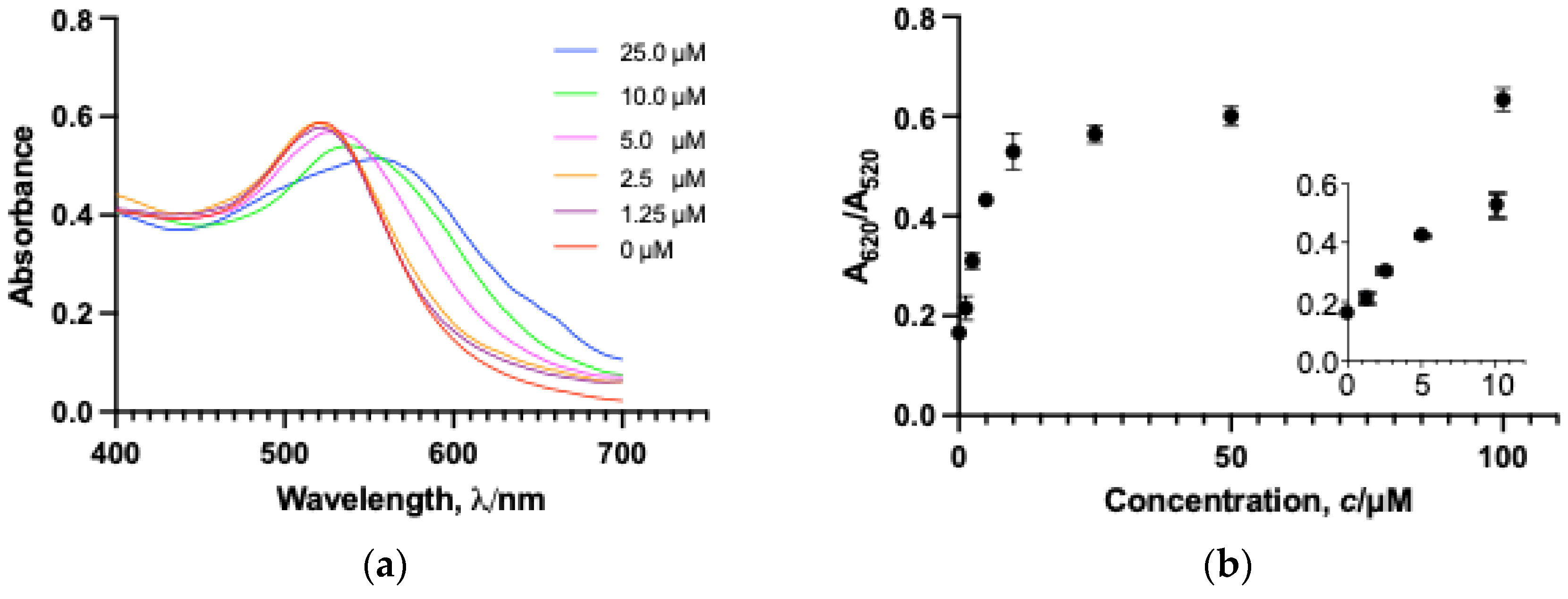

3.2. Assay Sensitivity

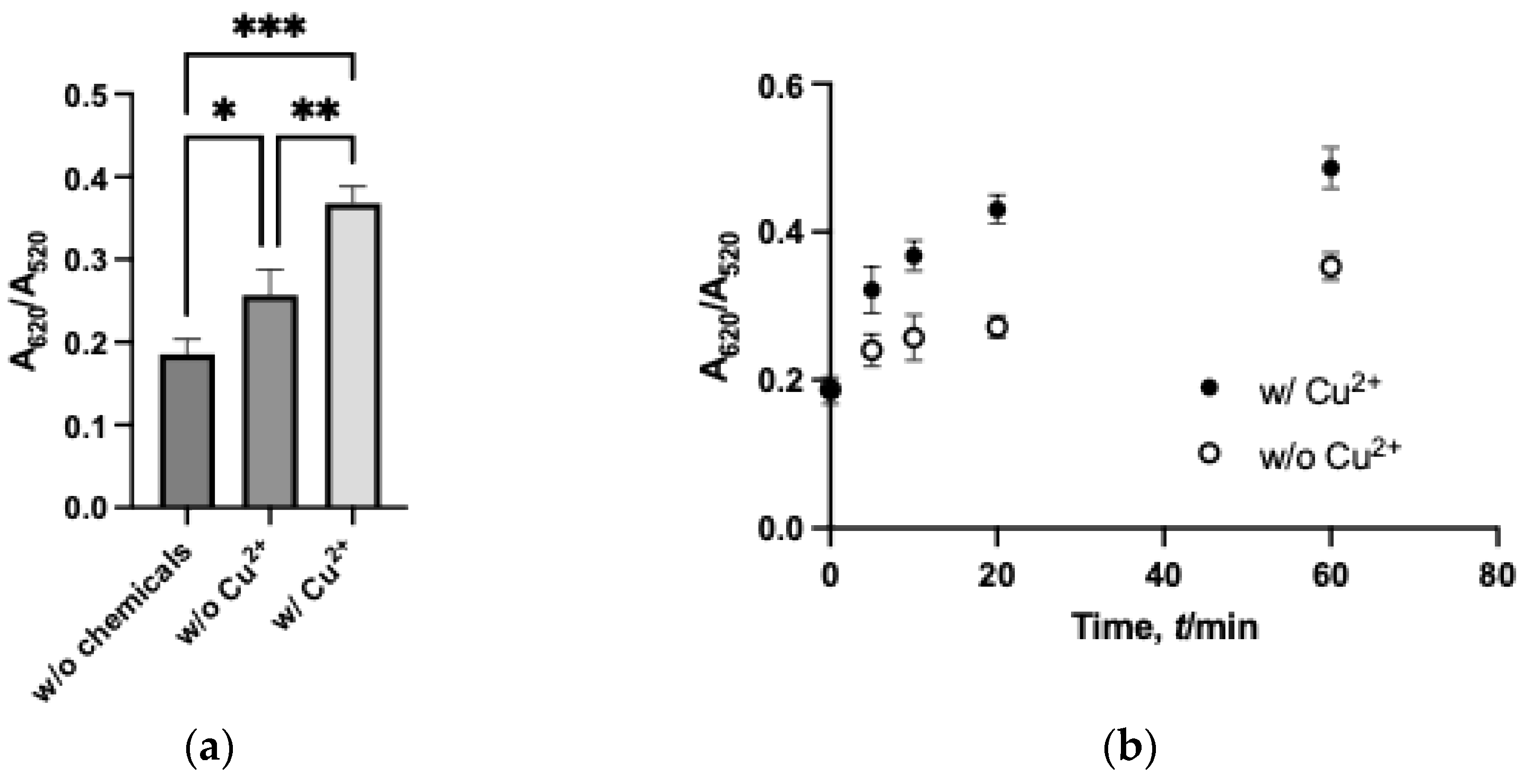

3.3. Assay Kinetics and Colloidal Stability

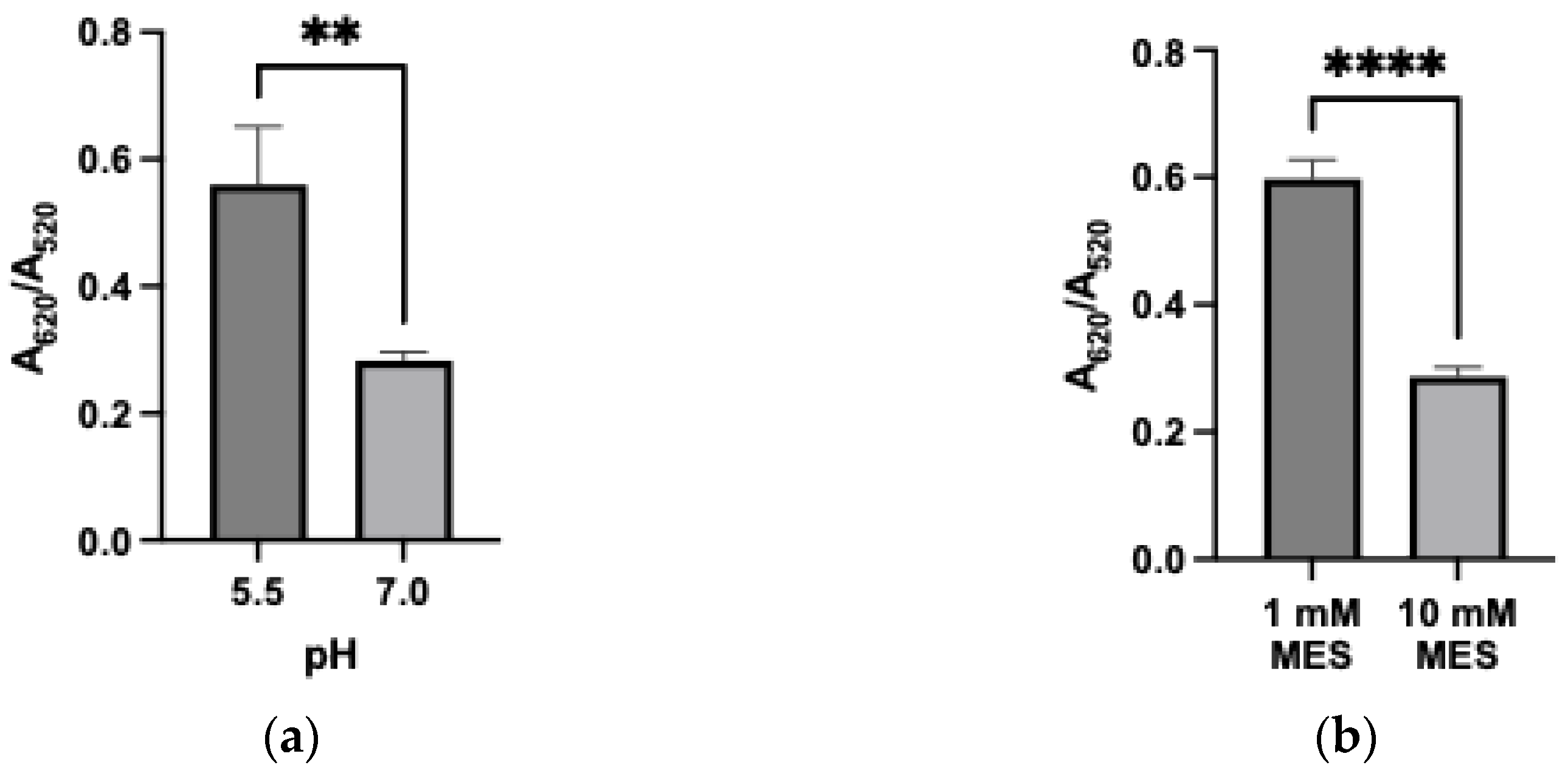

3.4. Effect of Buffer Conditions

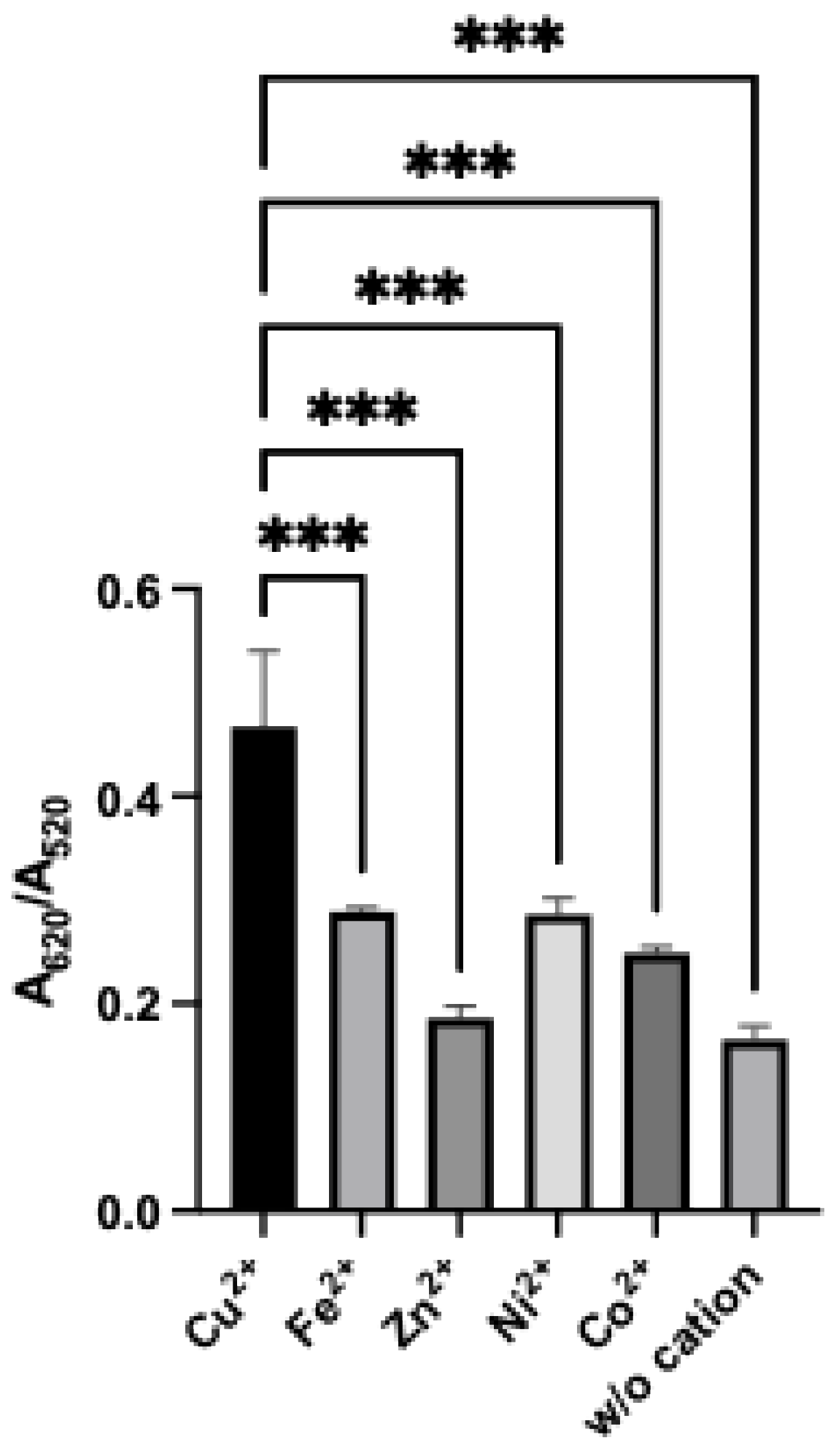

3.5. Effect of Metal Cation

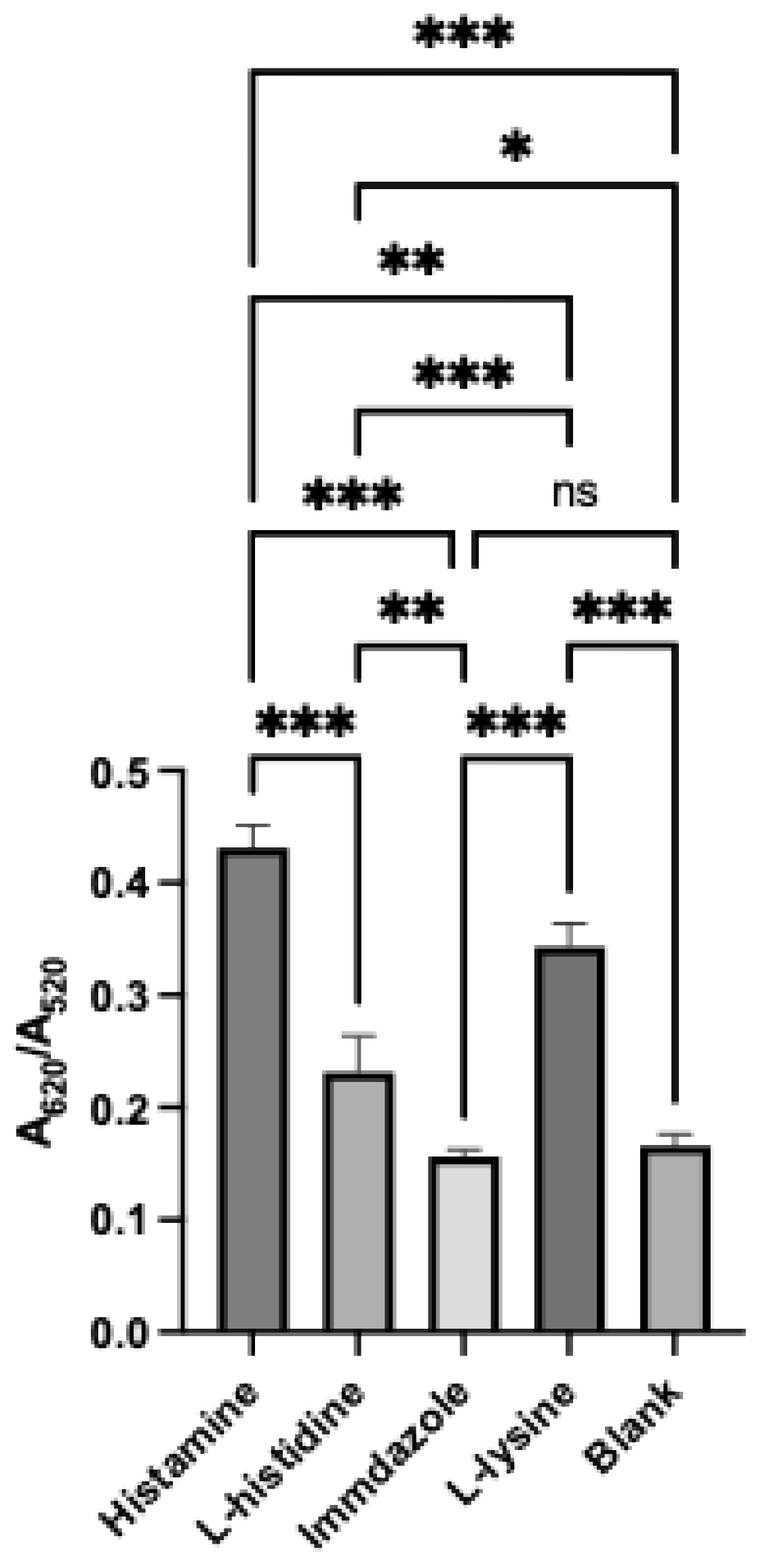

3.6. Assay Selectivity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qian, H.; Shu, C.; Xiao, L.; Wang, G. Histamine and histamine receptors: Roles in major depressive disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 825591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szukiewicz, D. Histaminergic System Activity in the Central Nervous System: The Role in Neurodevelopmental and Neurodegenerative Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Lei, Y.; Xu, Y.; Du, X.; Lin, L.; Luo, Y.; Xi, Y.; Guo, Y.; Niu, X.; Wang, Z.; et al. PRL2 negatively regulates FcεRI mediated activation of mast cells. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.-W.; Zhu, X.-Y.; Li, S.-Y.; Lin, S.-E.; Zhu, Y.-H.; Ji, K.; Chen, J.-J. Formononetin Inhibits Mast Cell Degranulation to Ameliorate Compound 48/80-Induced Pseudoallergic Reactions. Molecules 2023, 28, 5271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi-Pilehdarboni, H.; Rasouli, M. Histamine H1- and H2-receptors participate to provide metabolic energy differently. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022, 36, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ince, M.; Ruether, P. Histamine and antihistamines. Anaesth. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 22, 749–755. [Google Scholar]

- Kou, E.; Zhang, X.; Dong, B.; Wang, B.; Zhu, Y. Combination of H1 and H2 histamine receptor antagonists: Current knowledge and perspectives of a classic treatment strategy. Life 2024, 14, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carthy, E.; Elender, T. Histamine, Neuroinflammation and neurodevelopment: A review. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 680214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barocelli, E.; Ballabeni, V. Histamine in the control of gastric acid secretion: A topic review. Pharmacol. Rev. 2003, 47, 299–304. [Google Scholar]

- Tuomisto, L.; Lozeva, V.; Valjakka, A.; Lecklin, A. Modifying effects of histamine on circadian rhythms and neuronal excitability. Behav. Brain Res. 2001, 124, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.; Miszta, P.; Filipek, S. Molecular modeling of histamine receptors—Recent advances in drug discovery. Molecules 2021, 26, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Limjunyawong, N.; Peng, Q.; Schroeder, J.T.; Saini, S.; MacGlashan, D., Jr.; Dong, X.; Gao, L. Biological screening of a unique drug library targeting MRGPRX2. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 997389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.S.; Gong, J.; Liu, F.T.; Mohammed, U. Naturally occurring polyphenolic antioxidants modulate IgE-mediated mast cell activation. Immunology 2000, 100, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Bian, X.; Gu, W.Y.; Sun, B.; Gao, X.; Wu, J.L.; Li, N. Stand out from matrix: Ultrasensitive LC-MS/MS method for determination of histamine in complex biological samples using derivatization and solid phase extraction. Talanta 2021, 225, 122056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Hasan, E.; Sun, X.; Asif, M.; Aziz, A.; Lu, W.; Dong, C.; Shuang, S. Bridging biological and food monitoring: A colorimetric and fluorescent dual-mode sensor based on N-doped carbon dots for detection of pH and histamine. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 470, 134271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komori, K.; Komatsu, Y.; Nakane, M.; Sakai, Y. Bioelectrochemical detection of histamine release from basophilic leukemia cell line based on histamine dehydrogenase-modified cup-stacked carbon nanofibers. Bioelectrochemistry 2021, 138, 107719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xie, J.; Mei, J. A Review on Analytical Techniques for Quantitative Detection of Biogenic Amines in Aquatic Products. Chemosensors 2024, 12, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumalasaari, M.R.; Alfanaar, R.; Andreani, A.S. Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs): A versatile material for biosensor application. Talanta Open 2024, 9, 100327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldewach, H.; Chalati, T.; Woodroofe, M.N.; Bricklebank, N.; Sharrack, B.; Gardiner, P. Gold nanoparticle-based colorimetric biosensors. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Cheng, Y.; Qi, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, L.; Sun, T.; Gao, Z.; Zhu, M. Target-induced gold nanoparticles colorimetric sensing coupled with aptamer for rapid and high-sensitivity detecting kanamycin. Anal. Chim. Acta 2022, 1230, 340377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, J.; He, D. Smartphone-based surface plasmon resonance sensing platform for rapid detection of bacteria. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 13045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.; Yu, T.; Liu, D.; Xianyu, Y. Recent advances in gold nanoparticles-based biosensors for food safety detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 179, 113076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omping, J.; Unabia, R.; Reazo, L.; Lapening, M.; Lumod, R.; Ruda, A.; Rivera, R.B.; Sayson, N.L.; Latayada, F.; Capangpangan, R.; et al. Facile synthesis of PEGylated gold nanoparticles for enhanced colorimetric detection of histamine. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 14269–14278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, R.B.P.; Unabia, R.B.; Reazo, R.L.D.; Lapening, M.A.; Lumod, R.M.; Ruda, A.G.; Omping, J.L.; Magdadaro, M.R.D.; Sayson, N.L.B.; Latayada, F.S.; et al. Influence of the gold nanoparticle size on the colorimetric detection of histamine. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 33652–33661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Wang, S.; Zhao, W.; Zong, C.; Liang, A.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, X. Visual and photometric determination of histamine using unmodified gold nanoparticles. Microchim. Acta 2017, 184, 2249–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.; Tian, C.; Zhang, G.L.; Hao, H.; Hou, H.M. Detection of Histamine Based on Gold Nanoparticles with Dual Sensor System of Colorimetric and Fluorescence. Foods 2020, 9, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Nour, K.M.A.; Salam, E.T.A.; Soliman, H.M.; Orabi, A. Gold Nanoparticles as a Direct and Rapid Sensor for Sensitive Analytical Detection of Biogenic Amines. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unabia, R.B.; Reazo, R.L.D.; Rivera, R.R.B.P.; Lapening, M.A.; Omping, J.L.; Lumod, R.M.; Ruda, A.G.; Sayson, N.L.B.; Dumancas, G.; Malaluan, R.M.; et al. Dopamine-functionalized gold nanoparticles for colorimetric detection of histamine. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 17238–17246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, T.; Tan, E.M.M.; Cingil, H.E. L-cysteine gold nanoparticles for colorimetric and electrochemical detection of spermine and histamine. Microchem. J. 2024, 207, 112196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapenna, A.; Dell’Aglio, M.; Palazzo, G.; Mallardi, A. “Naked” gold nanoparticles as colorimetric reporters for biogenic amine detection. Colloids Surf. A 2020, 600, 124903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerga, T.M.; Skouridou, V.; Bermudo, M.C.; Bashammakh, A.S.; El-Shahawi, M.S.; Alyoubi, A.O.; O’Sullivan, C.K. Gold nanoparticle aptamer assay for the determination of histamine in foodstuffs. Microchim. Acta 2020, 187, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Gan, J.; Yang, Q.; Fu, L.; Wang, Y. Colorimetric detection of food freshness based on amine-responsive dopamine polymerization on gold nanoparticles. Talanta 2021, 234, 122706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, D.; Umapathi, R.; Oh, S.Y.; Cho, Y.; Huh, Y.S. Colorimetric visualization of histamine secreted by basophils based on DSP-functionalized gold nanoparticles. Anal. Methods 2022, 14, 269–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, N.; Park, B.; Lee, M.J.; Umapathi, R.; Oh, S.Y.; Cho, Y.; Huh, Y.S. Fabrication of Carbon Disulfide Added Colloidal Gold Colorimetric Sensor for the Rapid and On-Site Detection of Biogenic Amines. Sensors 2021, 21, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, R.B.P.; Lumod, R.M.; Unabia, R.B.; Reazo, R.L.D.; Ruda, A.G.; Lapening, M.A.; Omping, J.L.; Ceniza, A.P.; Sayson, N.L.B.; Latayada, F.S.; et al. Paper-based colorimetric sensor for histamine detection using dopamine-functionalized, size-varied gold nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 36148. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.Q.; Ye, B.C. Rapid and sensitive colorimetric visualization of phthalates using UTP-modified gold nanoparticles cross-linked by copper(ii). Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 11849–11851. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, R.; Huang, Z. Dual-channel colorimetric sensor based on metal ion mediated color transformation of AuNPs to identify the authenticity and origin of Atractylodis macrocephalae Rhizoma. Sens. Actuators B 2024, 400, 134920. [Google Scholar]

- Rasouli, Z.; Ghavami, R. Enhanced Sensitivity to Detection Nanomolar Level of Cu2+ Compared to Spectrophotometry Method by Functionalized Gold Nanoparticles: Design of Sensor Assisted by Exploiting First-order Data with Chemometrics. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2018, 191, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haiss, W.; Thanh, N.T.K.; Aveyard, J.; Fering, D.G. Determination of size and concentration of gold nanoparticles from UV-vis spectra. Anal. Chem. 2007, 79, 4215–4221. [Google Scholar]

- Irving, H.; Williams, R.J.P. The stability of transition-metal complexes. J. Chem. Soc. 1953, 3192–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, S. Critical evaluation of stability constants of metal-imidazole and metal-histamine systems. Pure Appl. Chem. 1997, 69, 1549–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mechanistic Category | Surface Modification | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dual recognition (electrostatic interaction and metal ion coordination) | Citrate | 1.25–10 μM | 0.95 μM | This work |

| Electrostatic interaction and/or hydrogen bonds | PEG | 180–895 μM * (20–100 ppm) | 9.357 μM | [23] |

| Citrate | 9–90 μM * (1–10 ppm) | 0.72 μM | [24] | |

| Citrate | 0.1–2.1 μM | 0.038 μM | [25] | |

| Citrate | 0.001–10.0 μM | 0.87 nM | [26] | |

| Citrate | 45–105 μM | 0.6μM | [27] | |

| Dopamine | 9–90 μM * (1–10 ppm) | 0.426 μM | [28] | |

| L-cysteine | 1–10 μM | 3.7 μM | [29] | |

| Naked | 0.2–0.4μM | 0.2μM | [30] | |

| Aptamer-based | H2 aptamer | 19–70 nM | 8 nM | [31] |

| Dopamine polymerization | PEG | 9–900 μM * (1–100 μg/mL) | 25 μM * (2.8 μg/mL) | [32] |

| Chemical reaction | dithiobis(succinimidylpropionate) (DSP) | 0.8–2.5 μM | 0.014 μM | [33] |

| Dithiocarbamate (DTC–BA) | ND | 50 μM (total biogenic amines) | [34] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Migita, S. Copper-Enhanced Gold Nanoparticle Sensor for Colorimetric Histamine Detection. Biophysica 2025, 5, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/biophysica5040059

Migita S. Copper-Enhanced Gold Nanoparticle Sensor for Colorimetric Histamine Detection. Biophysica. 2025; 5(4):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/biophysica5040059

Chicago/Turabian StyleMigita, Satoshi. 2025. "Copper-Enhanced Gold Nanoparticle Sensor for Colorimetric Histamine Detection" Biophysica 5, no. 4: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/biophysica5040059

APA StyleMigita, S. (2025). Copper-Enhanced Gold Nanoparticle Sensor for Colorimetric Histamine Detection. Biophysica, 5(4), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/biophysica5040059