1. Introduction

Rare earth elements (REEs), comprising the lanthanides, yttrium, and scandium, constitute a group of metals of exceptional technological and strategic importance. For decades, they have been indispensable for sustaining and advancing high-tech industries worldwide. Their unique physical and chemical properties are essential for diverse applications, including metallurgy, electrical engineering, petroleum refining, and green energy. Among these, the heavy rare earth elements (HREEs) are of particular significance due to their critical role in high-performance applications and their geopolitical supply risk [

1]. For instance, dysprosium is a critical component in permanent magnets for wind turbines [

2], yttrium enhances the hardness and wear resistance of structural ceramics [

3], gadolinium improves the mechanical properties of specialty alloys [

4], and ytterbium serves as a key dopant for laser crystals in solid-state and fiber laser applications [

5].

Global demand for rare earth elements continues to rise steadily [

6,

7]. To meet this demand, production volumes have increased significantly, by approximately 89% between 2019 and 2023 [

8] and reaching an estimated 390,000 tons in 2024 according to the U.S. Geological Survey [

9]. This growing demand, coupled with the geographical concentration of mining and processing capabilities, notably in China, has led major economic blocs such as the European Union to classify REEs as critical raw materials, highlighting concerns over supply security [

10].

To diversify supply beyond traditional ores, promising sources of rare earth elements are the process solutions generated during the acid leaching of apatite or other mineral concentrates [

11,

12,

13]. Utilizing these solutions for REEs co-extraction offers a dual benefit: it yields an additional valuable product while enhancing the purity of the industrial streams for subsequent processing [

14]. The primary methods for metal recovery from such aqueous feeds are solvent extraction [

15,

16] and sorption [

17,

18]. Given that these leachates typically feature low REE concentrations alongside a complex background of competing ions, solvent extraction using selective organic reagents remains one of the most widely applied recovery methods [

19,

20,

21].

Phosphate ores represent a critical global resource and a major potential source of rare earth elements. Russia’s extensive apatite deposits form a significant part of this resource base and could play a key role in mitigating the current REE supply deficit [

22]. While Russia presently extracts REEs mainly from loparite ore [

23], the largest portion of its total resources is contained in phosphate ores and remains largely unexploited. It is estimated that annual phosphoric acid production results in the loss of approximately 56,000 tons of REEs (including 23,000 tons of HREEs) to process streams.

The commercial viability of recovering REEs from such phosphate sources depends on both the economics of ore beneficiation and the efficiency of the downstream extraction process. While research to date has demonstrated the technical feasibility of co-extracting REEs as a by-product [

24,

25], modern industrial practices still result in significant losses. Typically, the heavy REE fraction predominantly remains in the phosphoric acid used for fertilizer production, whereas light REEs are largely discarded with the solid phosphogypsum waste [

26]. Consequently, developing efficient technologies for the comprehensive utilization of these process solutions represents a critical step toward sustainable development, aligning with the principles of rational environmental management and the transition to zero-waste processes in metallurgy.

Industrial phosphoric acid solutions are notably enriched with heavy rare earth elements, whose supply–demand gap is particularly acute [

27]. This makes such solutions a highly promising target for recovery research. For operations involving concentrated phosphoric acid media, di-(2-ethylhexyl)phosphoric acid (D2EHPA) has been established as the most effective extractant [

28].

However, the pronounced physicochemical similarity of rare earth elements means that thermodynamic data alone are insufficient to ensure their efficient recovery and separation, as the process can be kinetically limited. Therefore, identifying the rate-limiting step, which governs the overall extraction kinetics, is critical for elucidating the underlying mechanism and enabling process optimization.

The rate-limiting step in a heterogeneous extraction process can be either diffusion, chemical reaction, or a combination of both. A diffusion-controlled regime is marked by strong dependence on stirring intensity and a low apparent activation energy

(usually below 20 kJ/mol). Conversely, a chemically controlled regime exhibits weak dependence on agitation and a higher

(typically above 40 kJ/mol). Intermediate values suggest mixed control, where both mass transfer and reaction kinetics are significant [

29].

The mechanism and physicochemical principles of REE extraction have been thoroughly investigated various media [

30,

31]. For instance, in chloride media, the extraction of Nd(III) was found to be diffusion-controlled at the interface [

32]. Similarly, a study in nitrate media using tributyl phosphate demonstrated that the process rate is determined by complex formation at the phase interface [

33]. It is widely recognized that in many solvent extraction systems, the key chemical interactions occur specifically at the interfacial region [

34,

35].

Furthermore, the role of kinetics remains critical beyond the extraction stage itself. For example, an investigation in nitric media showed that the stripping rate of neodymium is nearly two orders of magnitude faster than that of lanthanum, enabling their effective separation [

36]. Kinetic considerations are also pivotal for separating elements with similar properties or isolating trace components from impurities. For example, one study demonstrated the separation of yttrium from iron (separation factor of 23) by exploiting their different rate-limiting steps at low temperature [

37]. Another showed that increasing temperature accelerates the extraction of lanthanum more significantly than that of nickel, favoring their separation at higher temperatures [

38].

However, such kinetic details are lacking for phosphoric acid media. The high ionic strength, strong complexing power of phosphate anions, low pH, and complex composition can fundamentally alter the extraction kinetics. Therefore, kinetic parameters from other systems are not directly applicable, necessitating a dedicated investigation in this industrially relevant yet poorly understood phosphoric acid medium.

In addition to the fundamental kinetic knowledge gap, practical considerations also motivate the exploration of alternative methods. A significant drawback of conventional solvent extraction is the reliance on toxic and volatile organic diluents, such as kerosene. This has spurred interest in alternative methods that eliminate the need for phase separation, including the use of ionic liquids [

39] and, notably, solid-phase extractants, which avoid the use of liquid organic diluents entirely.

The aim of this work is to investigate the kinetics of heavy rare earth element extraction from industrially relevant phosphoric acid solutions derived from apatite processing. The study provides a comparative analysis of two recovery methods: conventional solvent extraction and solid-phase extraction, both utilizing di-(2-ethylhexyl)phosphoric acid as the active agent. The specific objectives are to identify the rate-limiting steps, calculate the apparent activation energies, and establish optimal conditions for the efficient extraction and potential separation of lutetium, thulium, yttrium, erbium, and dysprosium.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation and Composition of Simulated Solutions

The extraction kinetics were studied using simulated industrial phosphoric acid solutions. Their composition was based on wet-process phosphoric acid derived from the sulfuric acid leaching of apatite concentrate, according to operational data provided by PJSC “PhosAgro” (The Balakovo Branch of Apatit, Saratov Region, Russia). The target composition is summarized in

Table 1 and is characterized by a high concentration of phosphoric acid, a significant content of sulfuric acid, and a complex mixture of minor impurities (F, Al, Ca, Fe, Si). The total rare earth oxide (TREO) content ranges from 0.07 to 0.10%.

The relative distribution of individual rare earth elements within this total, also provided by the industrial partner, is given in

Table 2. This distribution is dominated by light REEs, whereas the target heavy REEs of this study (Y, Dy, Er, Tm, Lu) collectively account for approximately 16% of the TREO.

Given the primary objective of this work—a fundamental kinetic analysis of individual heavy rare earth elements—a simplified model solution was rationally employed. The model faithfully replicates the aggressive and constant chemical background of the industrial stream: 4.5 M H3PO4 and 0.19 M H2SO4. This preserves the most critical and challenging aspect of the real system, namely the highly acidic, high-ionic-strength phosphate matrix. However, to eliminate cross-interference and allow precise determination of kinetic parameters for each element, the complex multi-component mixture of REEs present in the industrial feed was substituted with single-element solutions of the target HREEs: lutetium, thulium, yttrium, erbium, and dysprosium. The REE concentrations in these solutions ranged from 2 to 5 mmol/L, reflecting their typical content in the industrial feed.

Accordingly, the model solutions were prepared by dissolving a calculated mass of high-purity rare earth nitrate salt (, 99.9%, JSC LenReactiv, Saint Petersburg, Russia) in distilled water to prepare individual REE stock solutions. The exact concentration of each of them was verified by direct complexometric titration with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). A standard EDTA titrant solution (0.05 M) was prepared from a fixanal. For the titration, a 5 mL aliquot was mixed with 3 mL of a 0.1% ascorbic acid solution to reduce potential interfering ions, followed by the addition of 20 mL of an ammonium acetate-acetic acid buffer (pH 5.5). Xylenol orange (0.1% aqueous solution, alkalized) was used as a metallochromic indicator, and 5–7 drops were added to the mixture, imparting a violet color. The solution was then titrated with EDTA under constant stirring until the color changed sharply from violet to clear yellow, marking the endpoint. Each titration was performed in duplicate, and the average value was used to calculate the precise metal concentration.

2.2. Extraction Experiments and Kinetic Studies

The organic phase for solvent extraction consisted of di-(2-ethylhexyl)phosphoric acid (purity ≥ 95%, Leap Chem Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China) dissolved in a commercial kerosene diluent (TS-1 grade). Prior to each experiment, the extraction mixture was prepared ex situ in a separate vessel by combining the extractant and diluent at a predetermined volume ratio.

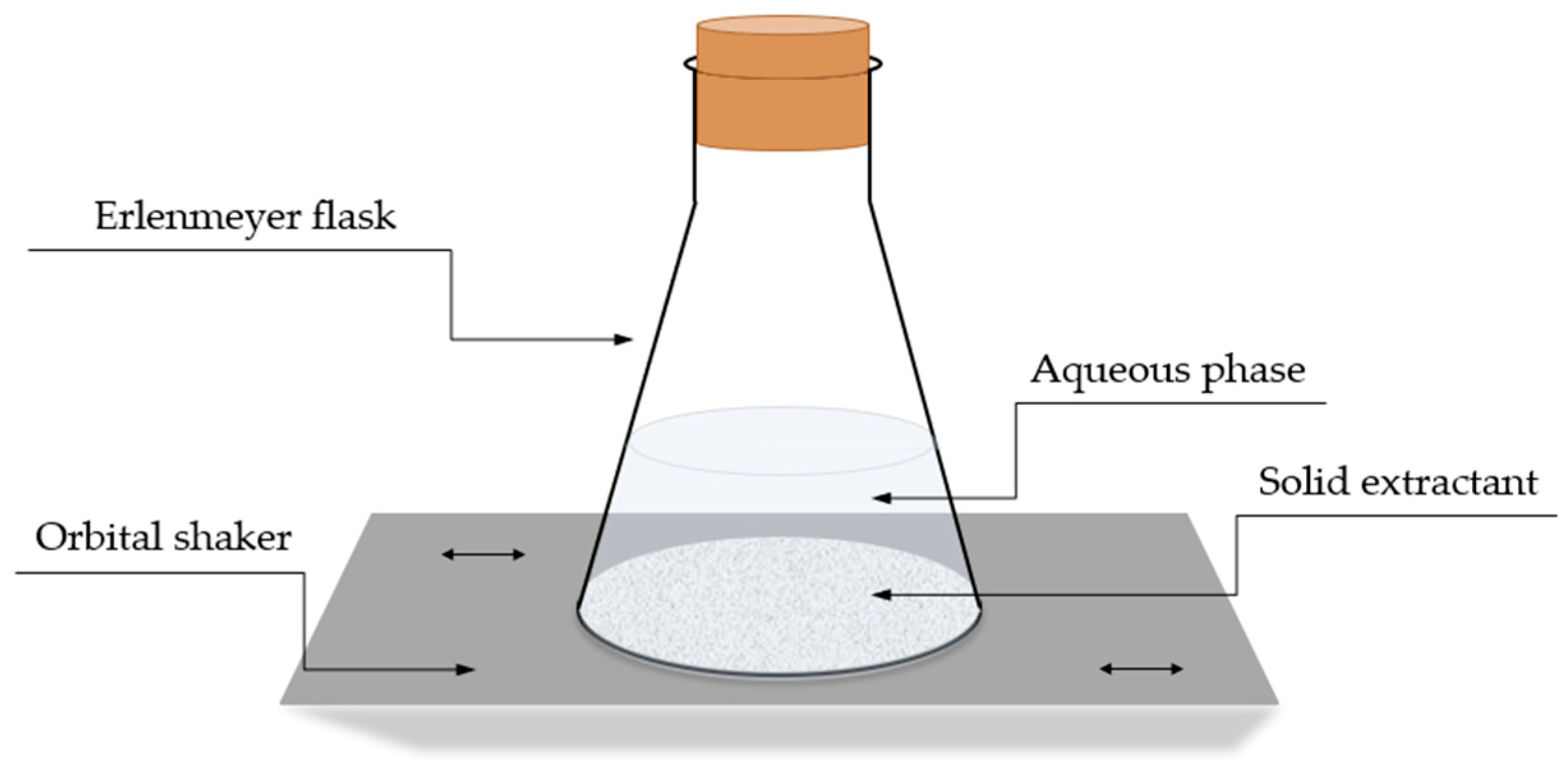

Extraction experiments were performed using an automated Parallel Auto-MATE Reactor System (H.E.L Group, Hemel Hempstead, UK). A schematic of the setup is presented in

Figure 1. The system comprises a reactor equipped with a magnetic stirrer, an electric heater, and a thermocouple for precise temperature control, and is designed to handle reaction mixtures with volumes up to 200 mL. An extraction experiment involved contacting the simulated aqueous solution with the organic phase in the reactor, with aqueous samples periodically withdrawn for kinetic analysis.

For solid-phase extraction, a ready-to-use polymeric sorbent impregnated with D2EHPA (Seplite LXCL-204, Sunresin New Materials Co., Ltd., Xi’an, China) was used. This material, provided directly by the production facility, is supplied as opaque white spherical beads with a bulk density of 0.4 g/mL.

A precisely weighed amount of the sorbent was measured using an analytical balance with a readability of ±0.0001 g and then mixed with the simulated solution in an Erlenmeyer flask together with a measured volume of the simulated aqueous solution. The flasks were then secured in a thermostated Shaking Incubator 3032 (GFL, Grossburgwedel, Germany), which provided orbital shaking to ensure consistent contact between the solid and aqueous phases (

Figure 2). Upon completion of the extraction period, the sorbent was separated by filtration, and the resulting aqueous phase was analyzed.

The concentration of rare earth elements in the phosphoric acid solutions, both before and after extraction, was determined by X-ray fluorescence spectrometry using a PANalytical Epsilon 3 energy-dispersive spectrometer (Malvern Panalytical Ltd., Almelo, The Netherlands). This technique allows for the analysis of elements from Na to Am in concentrations ranging from 10−4 to 100 wt.%.

To account for matrix effects such as absorption and spectral interference, a multi-point calibration was performed for each REE. Primary stock solutions were prepared from high-purity salts, and their concentrations were verified by complexometric titration with EDTA. Working standards were prepared by into a matrix-matched solution of 4.5 M H3PO4 and 0.19 M H2SO4, covering a concentration range from 0 to 0.5 M for each element.

The limits of detection and quantification were determined as three and ten times the standard deviation of the background signal, respectively, and were found to be <0.5 mmol/L for all REEs. Accuracy and precision were confirmed using independently prepared check standards and replicate measurements, yielding a relative standard deviation typically below 3%. Final quantification was performed by the instrument’s software using the fundamental parameters method with matrix corrections.

The extraction efficiency (

E, %) for each element was calculated according to the following formula:

where

and

are initial and final concentrations of metals in the aqueous phase.

The apparent activation energy

was calculated from rate constants determined at two temperatures using a two-point form of the Arrhenius equation. The derivation begins with the standard form for each temperature:

Taking the natural logarithm of the ratio

and simplifying yields:

Solving for

yields the expression used in this study:

where

R is the universal gas constant, J/(mol·K),

and

are the extraction temperatures (K),

and

are the reaction rate constants.

4. Discussion

4.1. Kinetic Analysis and Mechanism of Solvent Extraction

To determine the rate-limiting step, the kinetic data were analyzed using the linearized form of the kinetic equation

. The initial linear region was used to determine the rate under conditions of a constant rate-limiting step and negligible back-reaction influence. This methodology ensures a consistent basis for comparative kinetic analysis of different elements and conditions. Representative kinetic plots for lutetium extraction are shown in

Figure 8.

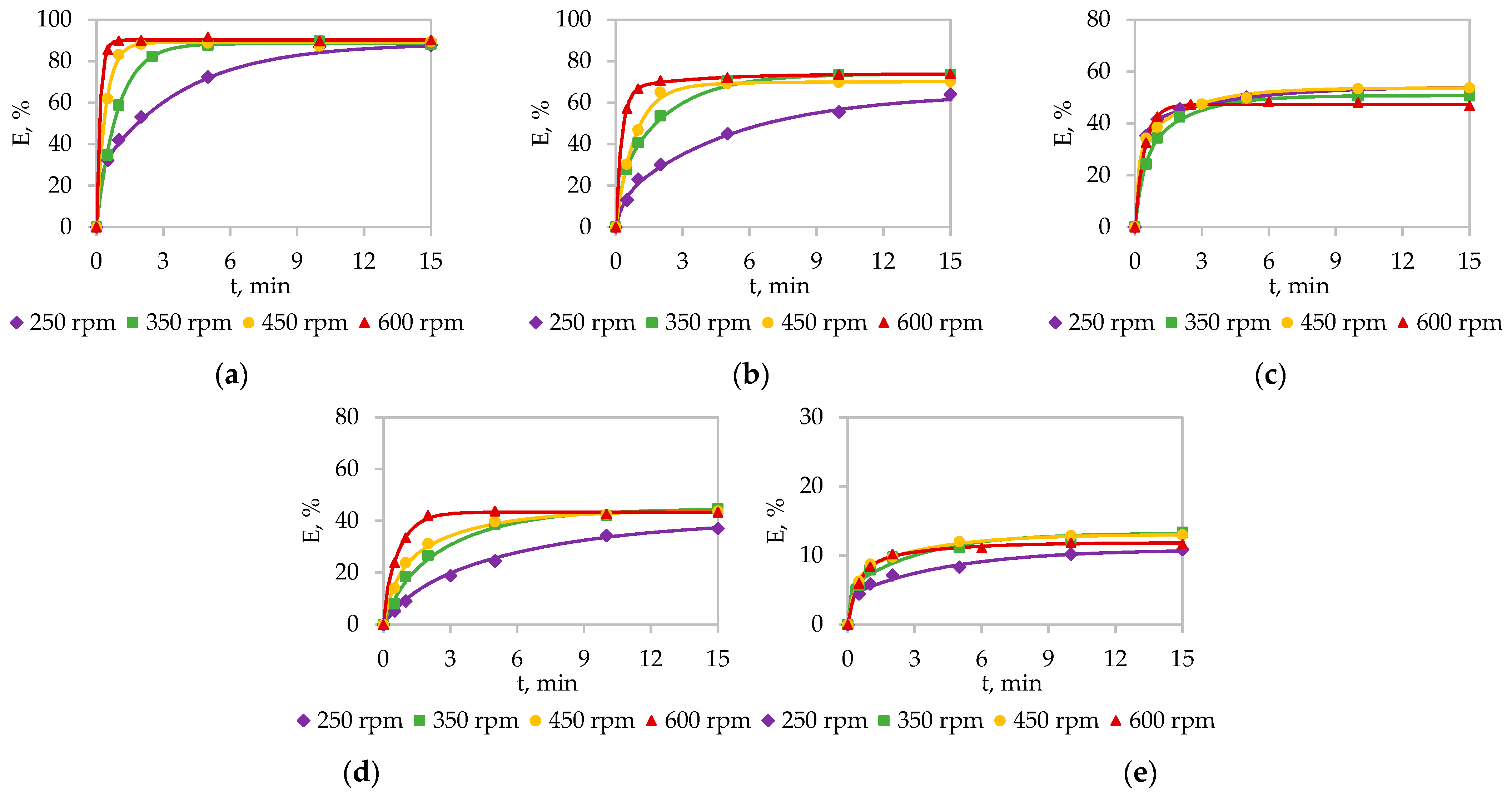

The slope of these linear plots, representing the apparent rate constant k, exhibited a significantly greater dependence on stirring intensity than on temperature. This observation strongly suggests that the overall extraction rate is limited by diffusion through the aqueous boundary layer. An identical dependence was confirmed for all other investigated heavy rare earth elements.

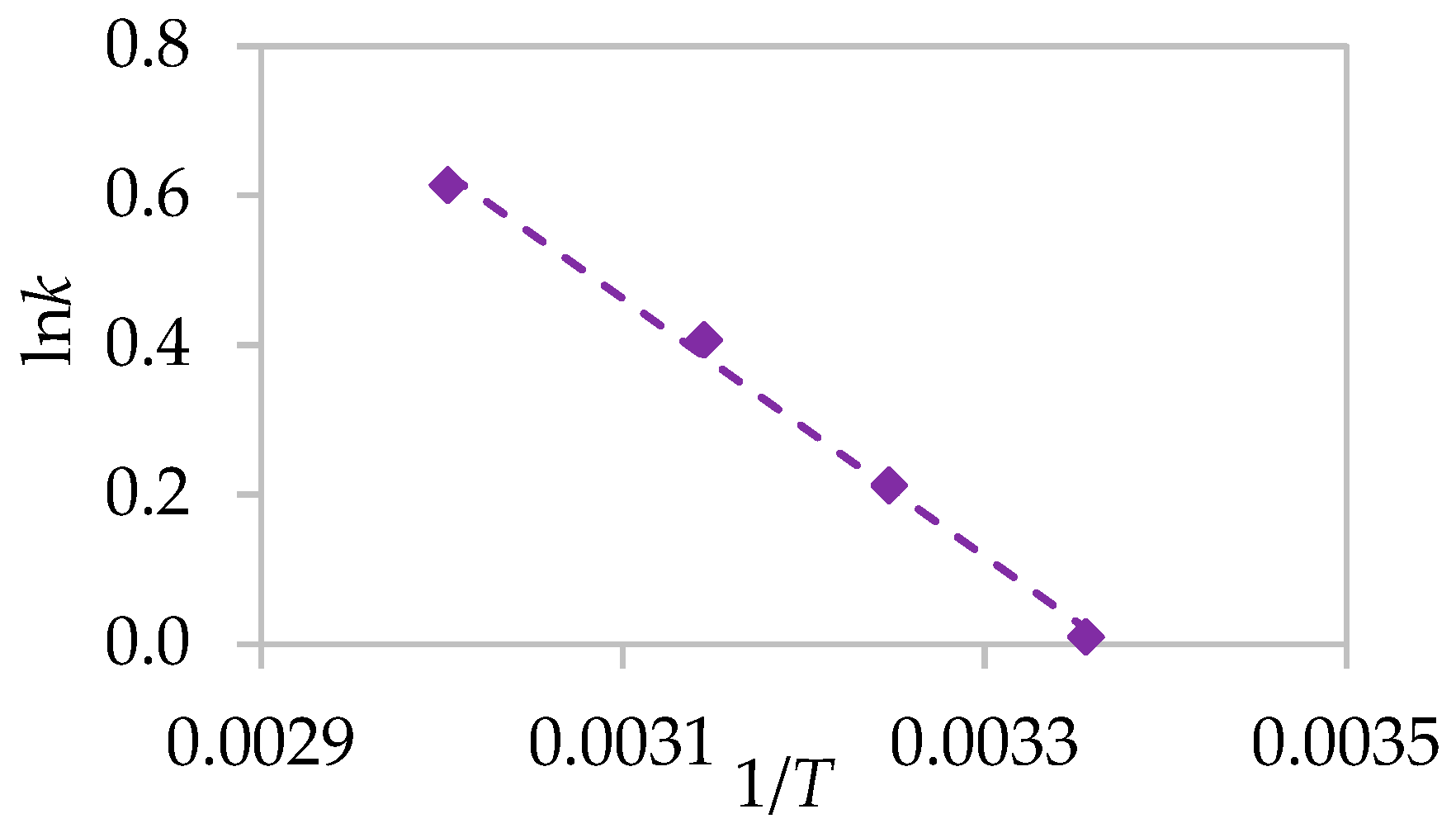

The activation energy for the extraction of each element was determined from an Arrhenius-type plot of

versus the reciprocal of absolute temperature (1/

T), as shown in

Figure 9. The calculated activation energy values, summarized in

Table 3, provide additional quantitative evidence for a diffusion-controlled rate-determining step.

4.2. Kinetic Analysis and Mechanism of Solid-Phase Extraction

The kinetic parameters derived from fitting the data to models (5–11), along with the coefficients of determination (

), are summarized in

Table 4.

While pseudo-second-order kinetics are frequently used to model the solid-phase extraction of REEs from acidic media [

42,

48], the analysis performed in this work suggests a different rate-determining mechanism. The application of diffusion-based models—specifically, the homogeneous particle diffusion and Elovich models—yielded consistently high correlation coefficients (

). Moreover, the close correspondence between the experimental and model-predicted sorption capacities validates the use of these diffusion models. Collectively, these results strongly indicate that the extraction of heavy REE ions in this system is predominantly controlled by diffusion.

A direct comparison of the two shrinking core model variants reveals that the internal (gel) diffusion-controlled mechanism provides a markedly superior fit to the experimental data over the chemical reaction-controlled mechanism. This result serves as an independent and compelling line of evidence reinforcing the conclusion of diffusion-limited kinetics.

The increase in the apparent rate constants for diffusion-based models with temperature indicates a reduction in diffusional resistance, a trend that is also influenced by the thermally activated nature of the chemical interaction at the functional sites. When modeling REE extraction kinetics with the Elovich equation, the parameter

α is considered an alternative form of the “rate constant” [

49]. The calculated values of

α (initial sorption rate) also increase with rising temperature from 298 to 333 K, which suggests chemisorption behavior. Conversely, the reciprocal of the desorption constant (1/

β), representing the number of available interaction sites, showed only a minor decrease.

The data in

Table 4 show that the initial sorption rate significantly exceeds the corresponding desorption rate. This pronounced difference can be reasonably explained by the high initial availability and favorable accessibility of functional groups of D2EHPA on the surface of the polymeric matrix to lanthanide ions in the bulk solution.

To elucidate the extraction mechanism, the kinetics were analyzed using the Weber-Morris intraparticle diffusion model (

Figure 10).

Linear regions of the corresponding plots do not extend over the full duration of the extraction process, demonstrating that intraparticle diffusion alone does not govern the overall kinetics. The observed deviations from linearity at the origin, along with the distinct multilinear segments, are characteristic of a process where both external (film) and internal (intraparticle) diffusion contribute significantly to the rate limitation [

50]. The sorption dynamics are characterized by an initially fast uptake, followed by a pronounced deceleration. This trend is consistent with the progressive saturation of easily accessible surface sites and the increasing diffusional resistance as pores within the polymer matrix become occupied.

A process is typically considered to be film-diffusion controlled when the activation energy is below 20 kJ/mol, while

values in the range of 20–40 kJ/mol suggest a mixed regime where diffusion plays a partial but significant role [

44]. The activation energy values derived in this study from the Elovich and homogeneous particle diffusion models (see

Table 5 and

Figure 11) fall predominantly within the latter range. This result strongly supports the conclusion that the extraction kinetics are governed by a mixed mechanism involving both internal (intraparticle) and external (film) diffusion [

48].

The analysis of activation energies reveals a temperature-dependent shift in the extraction mechanism. At lower temperatures (298–318 K), the calculated values (<20 kJ/mol) indicate a process predominantly limited by both intraparticle and film diffusion. However, as the temperature increases, the derive rise, suggesting a transition to a mixed control regime, where the activation energy for the chemical reaction step becomes kinetically competitive with that of diffusion.

This transition can be attributed to the concurrent effects of temperature on the thermodynamics of the extraction reaction and the physical properties of the polymeric sorbent. First, the extraction with D2EHPA is exothermic; therefore, according to Le Chatelier’s principle, increasing the temperature shifts the equilibrium toward the endothermic reverse reaction (stripping), effectively raising the energy barrier for the forward chemical step. Second, elevated temperature likely enhances the swelling of the polymer matrix, which can alter internal diffusional pathways and resistance.

As a result of these combined effects, the intrinsic rate of the chemical reaction becomes comparable to the rate of mass transfer. This shift in the kinetic balance manifests as an increase in the apparent activation energy into the range of 20–40 kJ/mol, which is characteristic of a mixed diffusion-chemical control regime.

4.3. Comparative Analysis of Solvent and Solid-Phase Extraction Kinetics

A direct comparison reveals a fundamental trade-off between process intensity and operational simplicity.

Solvent extraction is characterized by fast kinetics (equilibrium within 2–3 min) and high efficiency (>90% for Lu), governed by a diffusion-controlled mechanism ( < 23.1 kJ/mol). This necessitates efficient agitation in mixer-settler units for industrial scale-up. Its main drawback is the reliance on volatile organic diluents (e.g., kerosene), which introduces environmental, safety, and health concerns, as well as complications in solvent management and recovery.

Solid-phase extraction, in contrast, offers diluent-free operation, reducing environmental footprint and simplifying waste handling. However, it exhibits slower kinetics (~60 min to equilibrium) and a more complex mechanism that transitions toward mixed chemical-diffusional control at higher temperatures (20–40 kJ/mol).

Consequently, solvent extraction is the preferred choice for high-throughput applications where maximizing processing speed and yield are paramount. Solid-phase extraction presents a viable and more sustainable alternative for niche applications, smaller-scale operations, or contexts with stringent environmental regulations, where its slower kinetics may be economically offset by the high value of the product or the operational benefits of eliminating organic solvents.

A comparative summary of the key kinetic and operational parameters for both methods is provided in

Table 6.

5. Conclusions

This study provides such an analysis for heavy REEs from industrial phosphoric acid solutions derived from apatite processing using di-(2-ethylhexyl)phosphoric acid in both solvent and solid-phase extraction methods.

A distinct trend of progressively lower extraction efficiency with decreasing atomic number was observed, consistent with the diminishing chemical activity across the lanthanide series due to the lanthanide contraction.

For solvent extraction, the process kinetics exhibited a much stronger dependence on stirring intensity than on temperature. The low activation energies calculated ( < 23.1 kJ/mol) provide quantitative confirmation of a diffusion-controlled mechanism.

For solid-phase extraction, kinetic analysis via the Elovich and homogeneous particle diffusion models revealed a mechanism governed by a combination of film and intraparticle diffusion at lower temperatures, which shifts toward a mixed chemical-diffusional control at higher temperatures.

Based on the kinetic analysis, the following optimal conditions were established:

Solvent extraction: 298 K, 350 rpm, 20 vol.% D2EHPA in kerosene, = 2:1.

Solid-phase extraction: 298 K, 100 opm, solid-to-liquid ratio = 1:10.

These results provide a scientific foundation for process design, directly informing critical engineering choices such as agitator specification, stage configuration, and temperature control to maximize recovery and selectivity.

To advance toward practical implementation, future work should focus on:

- 3.

Designing a separation flowsheet using the established selectivity and optimal conditions for sequential HREEs recovery;

- 4.

Assessing closed-cycle performance, including sorbent stability and stripping efficiency.