Simulation of the Influence of Braking System Damage on Vehicle Driving Safety

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Operational Conditions and Examples of Braking System Damage

- •

- Brake disc cracking. Brake disc cracks often become initiated under conditions of extreme thermal or mechanical load. The initiation of cracks can be described using a model of thermal stress resulting from rapid heating followed by subsequent cooling of the disc. This process generates alternating stresses that may exceed the material’s yield strength or cause localised fatigue of the material. Once initiated, cracks propagate under the influence of subsequent braking cycles. Research conducted by the authors of [18] demonstrated that small cracks do not affect the migration of hot spots, as the hot spot moves above the crack. However, when the crack reaches a critical length, heat becomes concentrated within the crack, accelerating its growth and thereby reducing the service life of the disc.

- •

- Surface wear and the degradation of the disc material. In parallel with cracking, the disc surface undergoes intensive abrasion and oxidation. The authors of [19] analysed a grey cast iron disc, demonstrating that tribo-oxidation processes and thermal cracking interact in the mechanism of disc surface degradation.

- •

- Geometric deformations. Brake discs may undergo permanent geometric deformations as a result of cyclical heating and cooling (volume changes, thermal expansion) as well as mechanical loads from friction and caliper forces. These deformations result in damped residual stresses, uneven wear, disc run-out, and increased vibrations. Deformation can lead to localised increases in pressure on the friction lining, thereby accelerating surface wear or initiating additional cracks.

- •

- Friction wear of the disc-pad pair. Friction elements are subject to wear due to cyclical friction. The loss of friction material leads, among other effects, to changes in the contact geometry and an increase in local temperature.

- •

- Corrosion and seizure of moving components. Corrosion of the disc surface, brake pad guides, or caliper pistons reduces the efficiency of the self-adjustment mechanism and leads to seizures or single-side friction.

- •

- Hydraulic and operational damage. Leaks in brake lines, degradation of brake fluid, and air entrapment can indirectly contribute to the wear and deterioration of friction components.

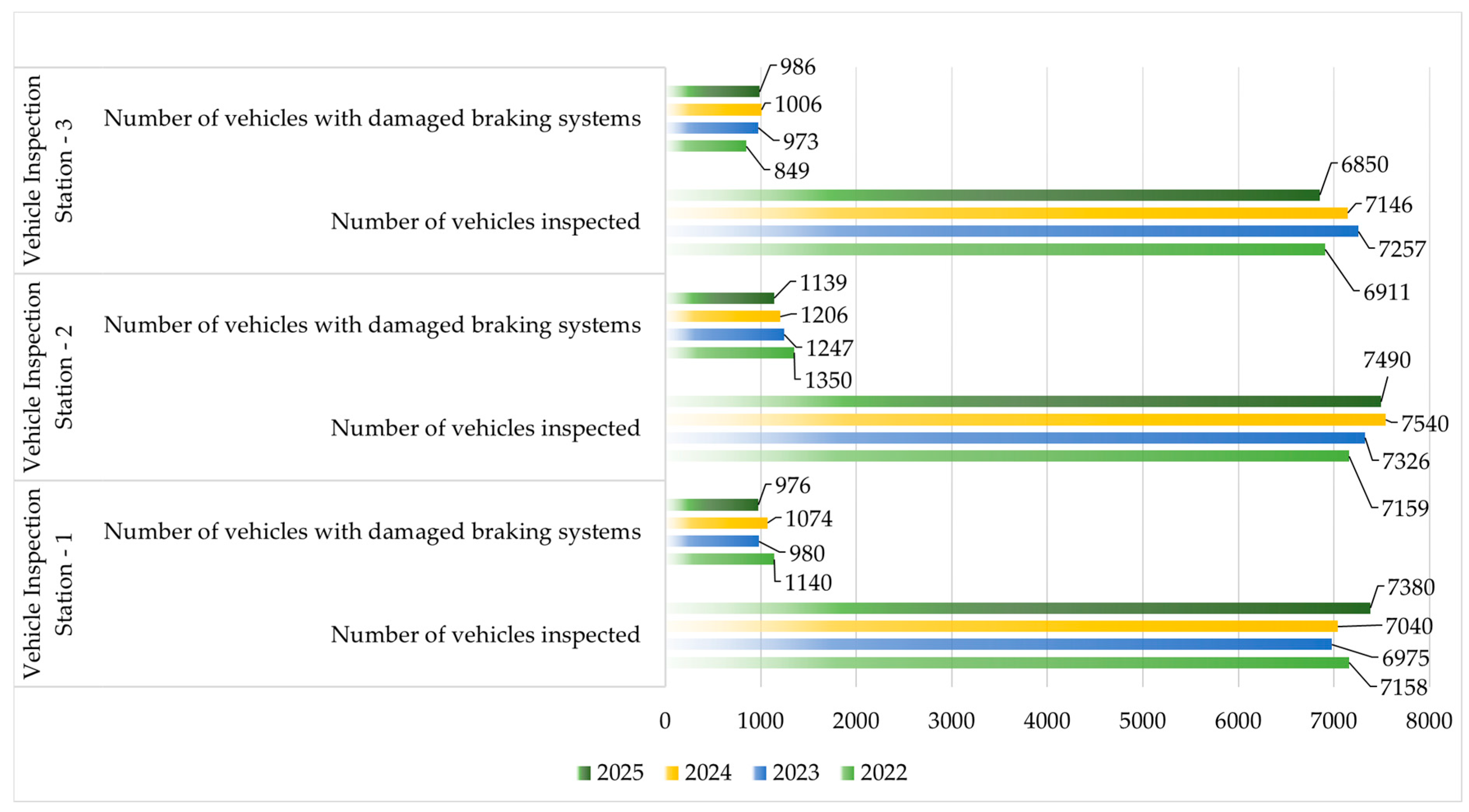

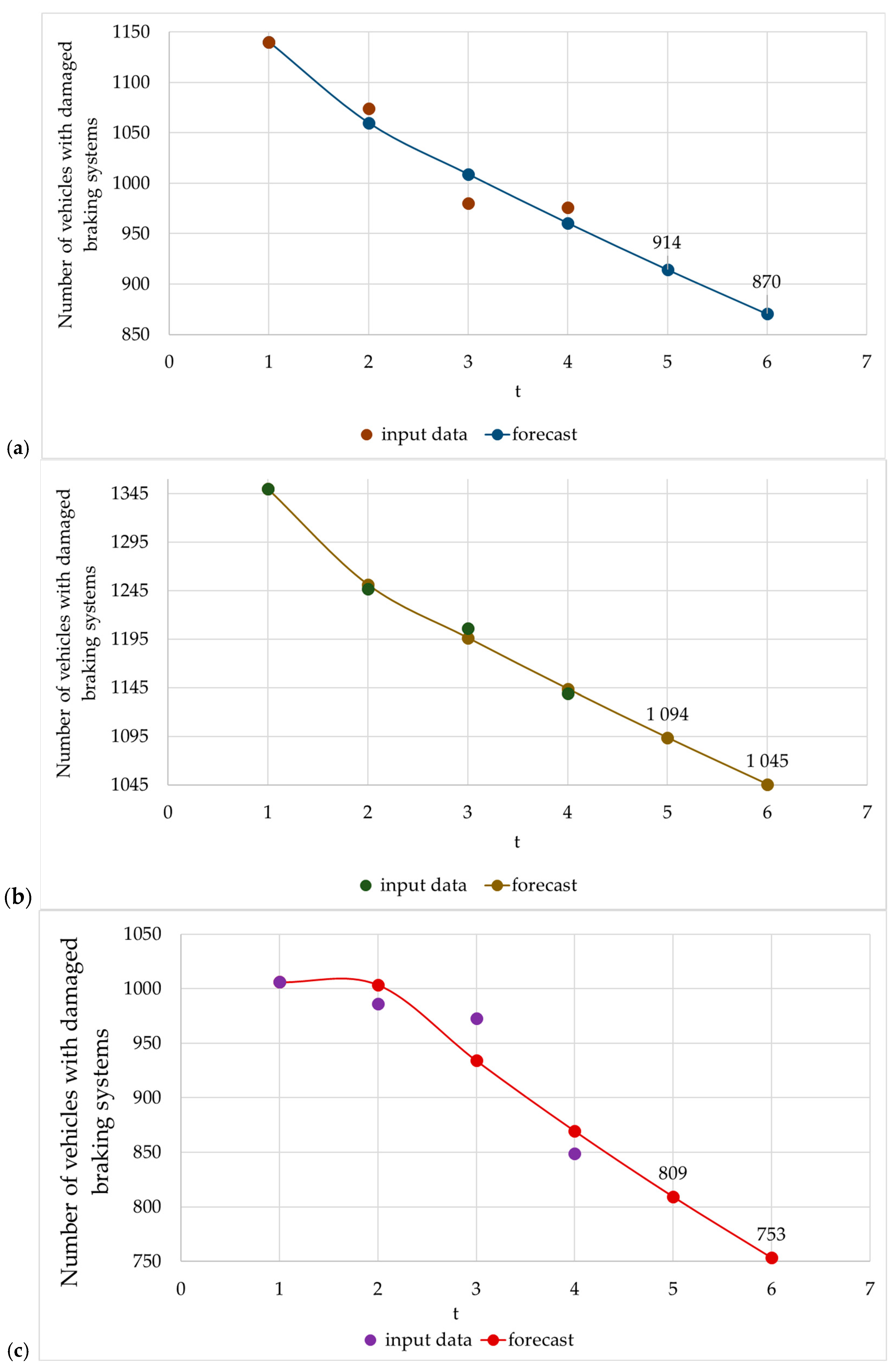

3. Analysis and Forecast of the Number of Vehicles with Damaged Braking Systems

4. Simulation Conditions

4.1. Road Incident Simulation Software

4.2. Vehicle Characteristics

- •

- Truck: length × width × height: 5875 × 2490 × 3530 mm,

- •

- Semitrailer: length × width × height: 13,950 × 2550 × 3970 mm

- •

- Number of axles: the truck: 2, the semitrailer: 3

- •

- Truck: kerb weight: 6568 kg, gross vehicle weight rating: 18,000 kg,

- •

- Semitrailer: kerb weight: 6200 kg, gross vehicle weight rating: 35,000 kg,

- •

- Maximum engine power of the truck: 324 kW at 1900 rpm,

- •

- Efficiency of the correctly operating service brake *: the truck: 108 kN, the semitrailer: 210 kN

- •

- Length × width × height: 4344 × 1845 × 1637 mm,

- •

- Number of axles: 2,

- •

- Wheelbase: 2702 mm,

- •

- First axle wheel track: 1545 mm, the second axle: 1547 mm,

- •

- Kerb weight: 1428 kg, gross vehicle weight rating: 1953 kg,

- •

- Maximum engine power: 103 kW at 6000 rpm,

- •

- Efficiency of the correctly operating service brake: 18.7 kN.

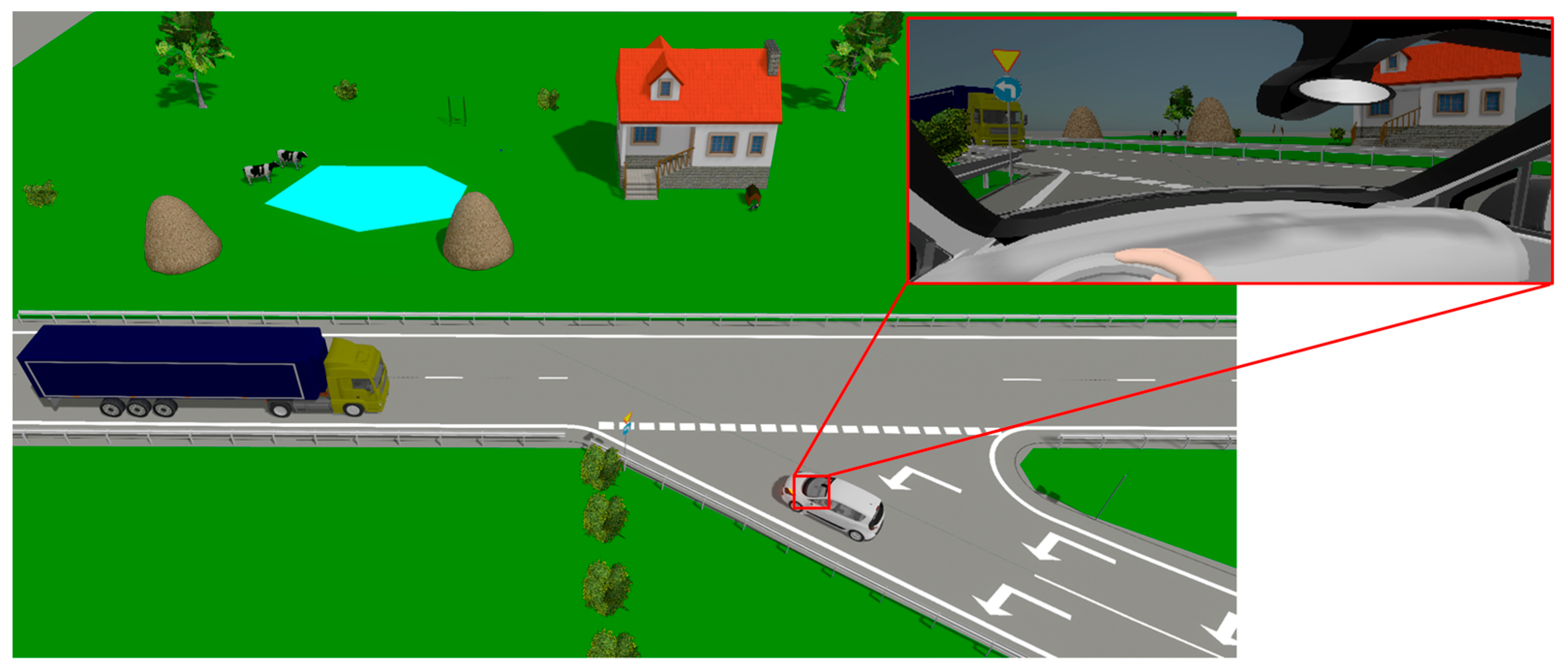

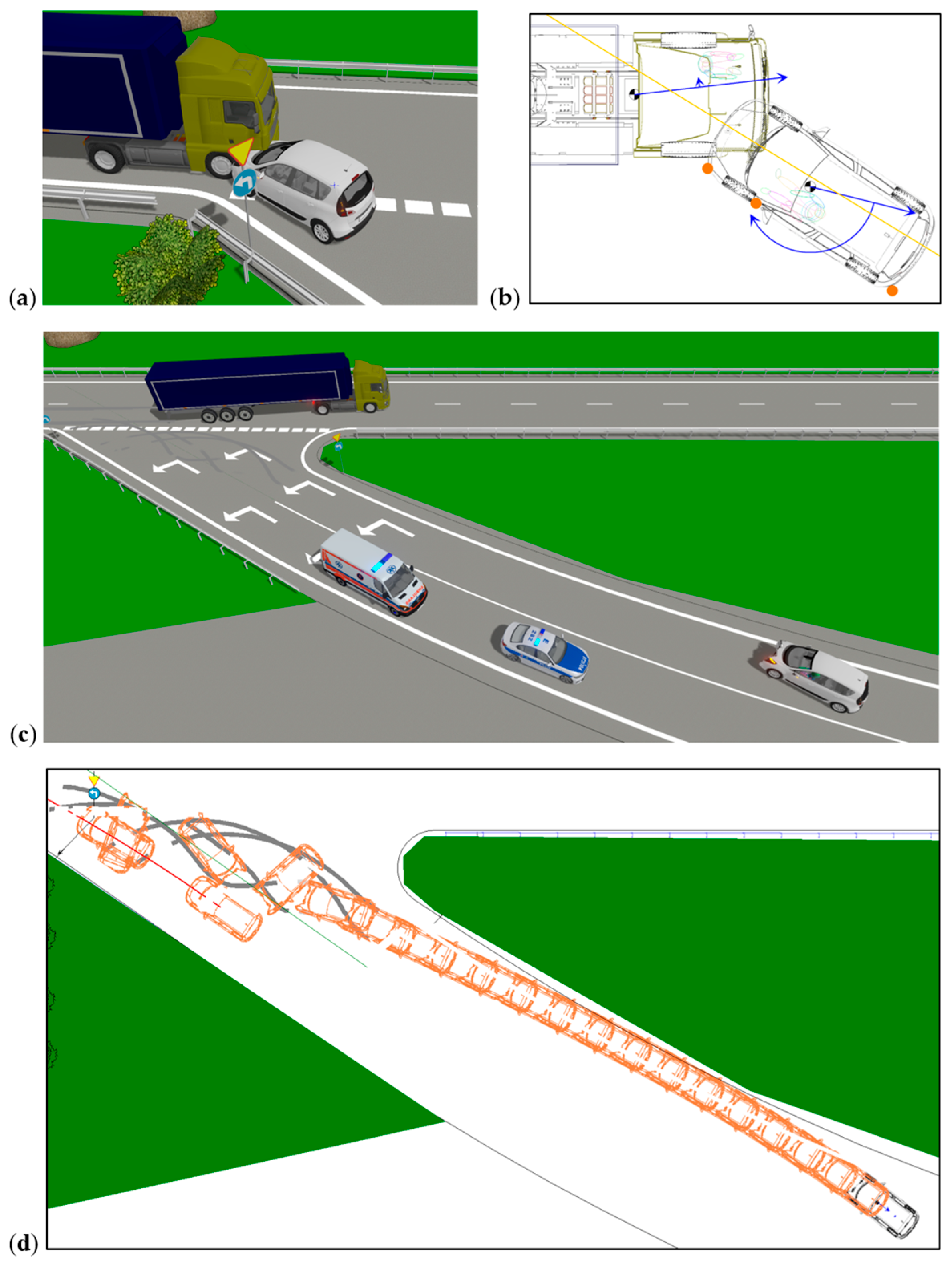

4.3. Traffic Environment

- •

- Grip coefficient of adhesion—

- •

- Slide coefficient of adhesion—

- •

- Rolling resistance coefficient—

5. Simulation Results

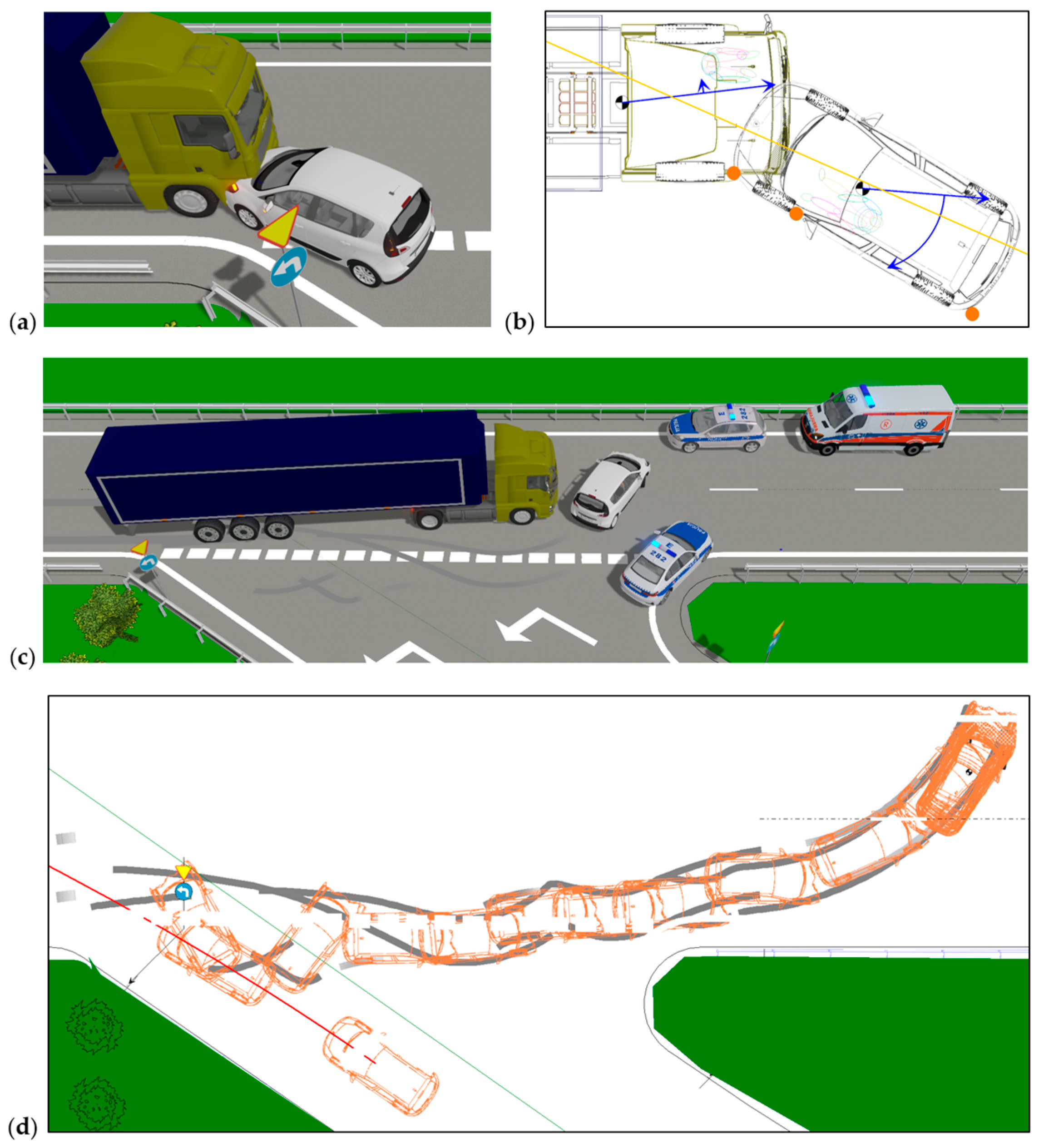

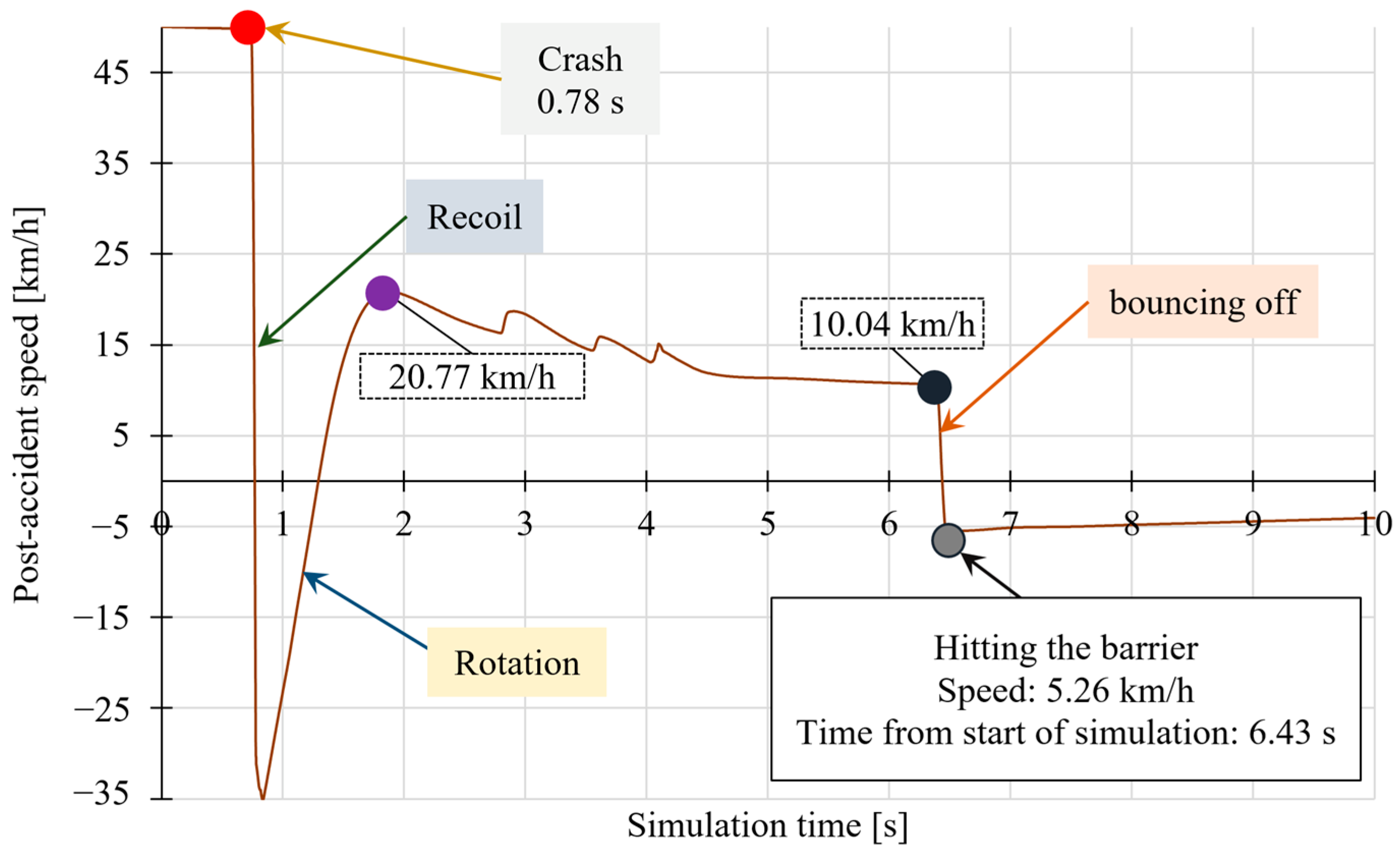

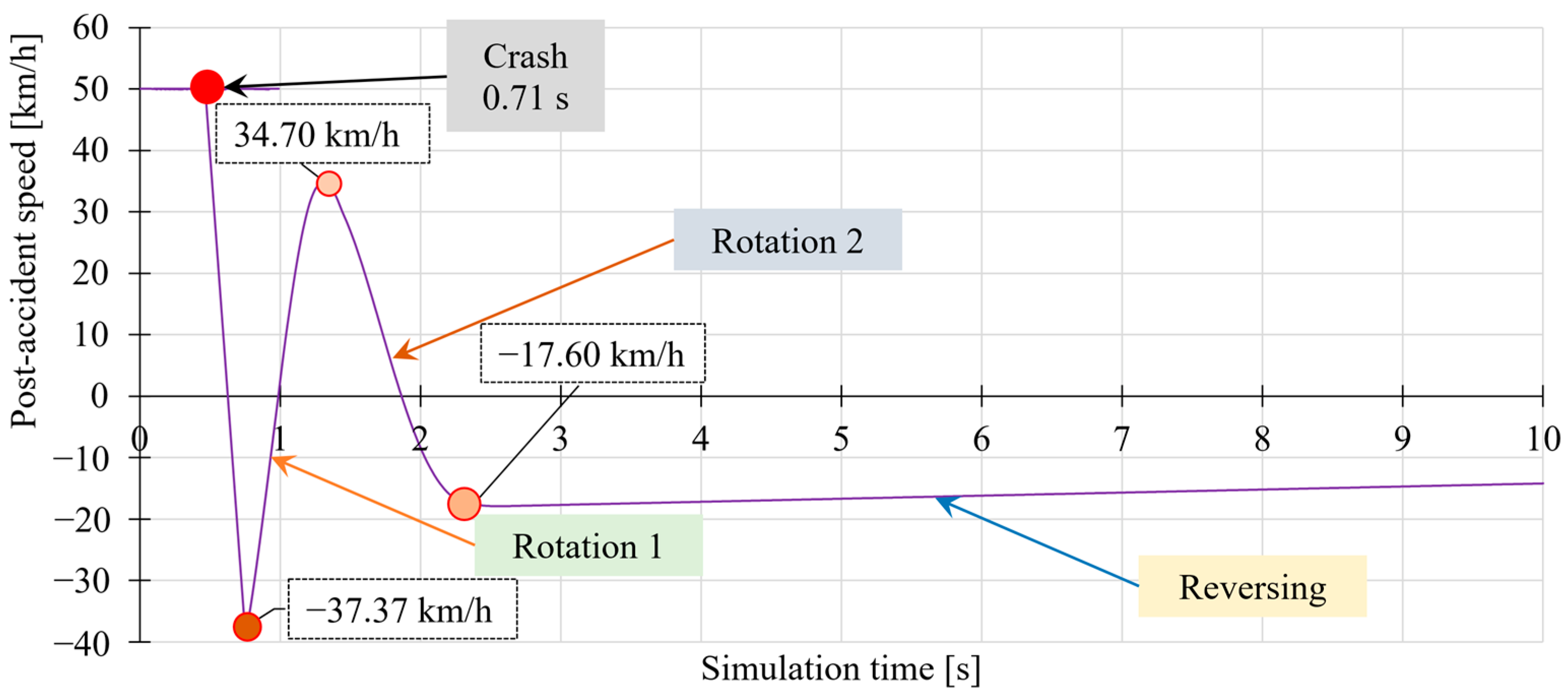

5.1. Post-Accident Vehicle Positions and Trajectories

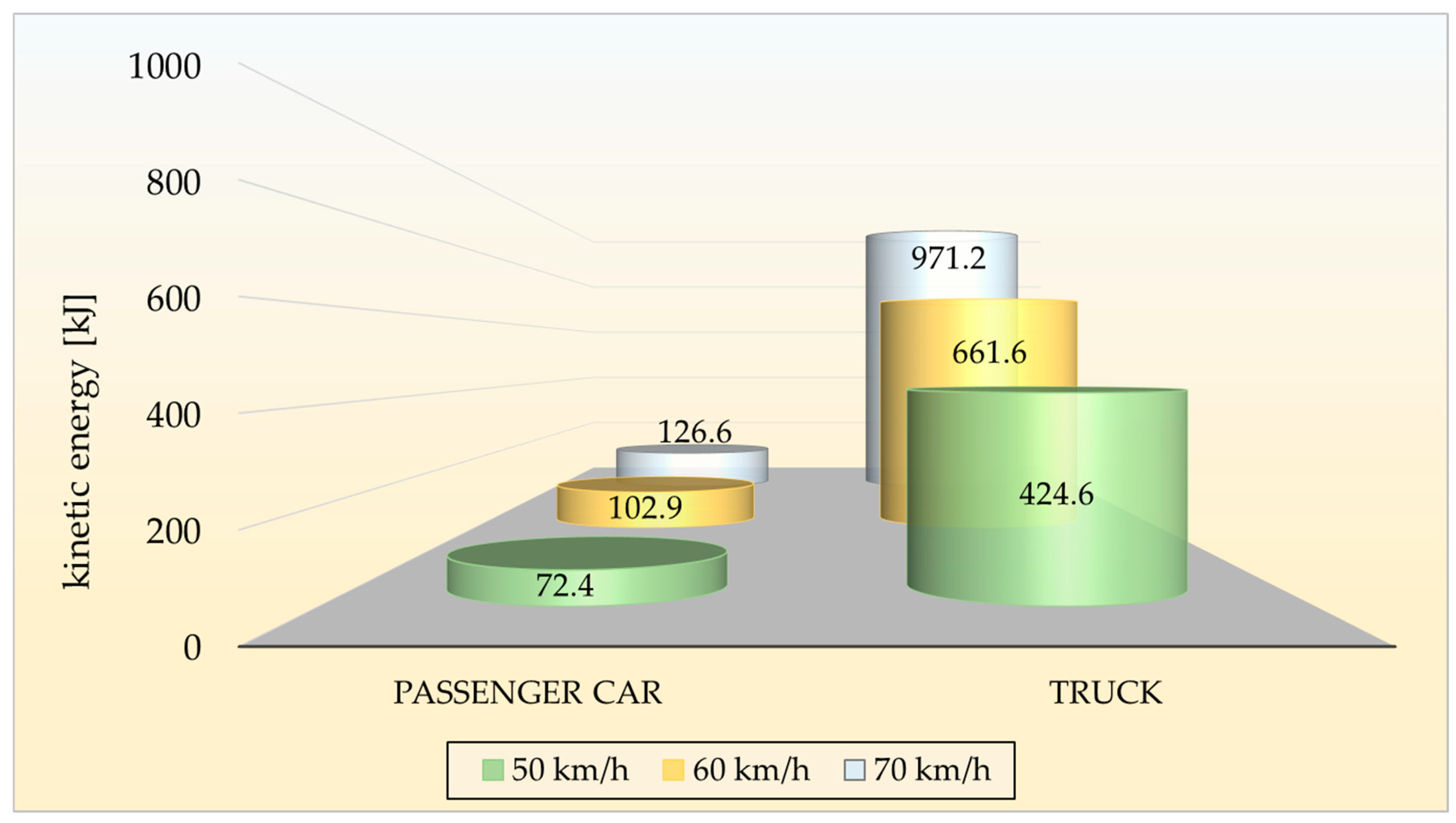

5.2. Kinetic Energy at the Moment of the Collision

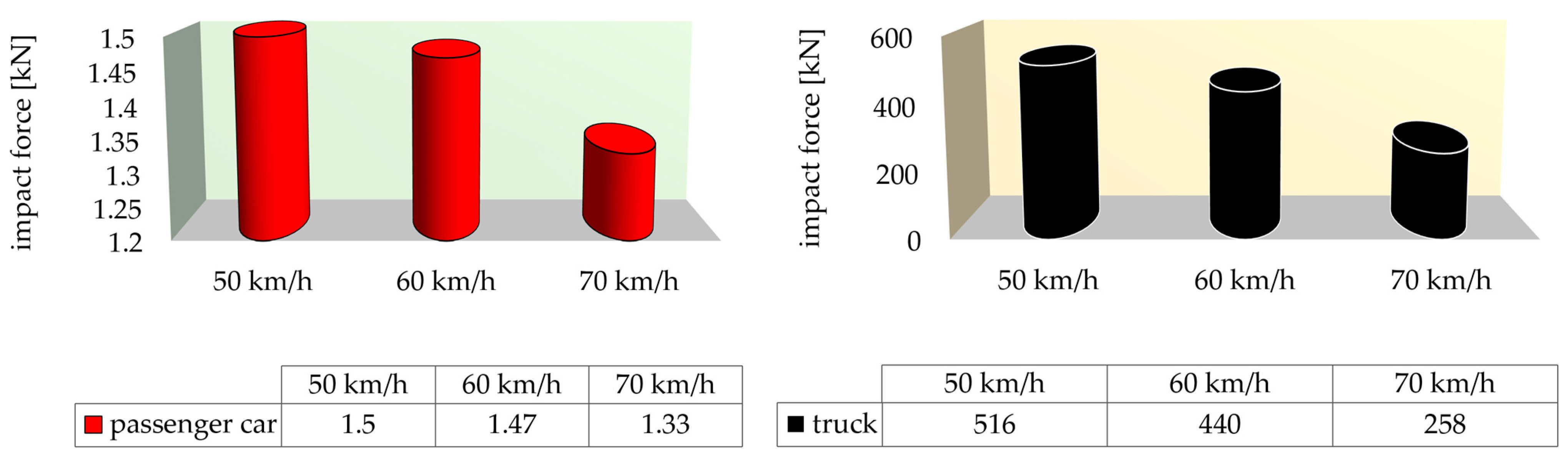

5.3. Resultant Force

5.4. Acceleration Acting on the Car

- •

- for a truck speed of 50 km/h—0.64 G,

- •

- for a truck speed of 60 km/h—0.72 G,

- •

- for a truck speed of 70 km/h—0.50 G.

6. Summary and Conclusions

- •

- As the truck’s speed increased from 50 km/h to 70 km/h, the total kinetic energy of the system nearly doubled.

- •

- The kinetic energy of the car constituted a small percentage of the total energy of the system (below 15%); however, that vehicle absorbed over 80% of deformation energy, resulting in a front-end deformation of approximately 0.6 m.

- •

- An increase in speed by 20 km/h led to a rise in kinetic energy by approximately 96%, indicating a sharp increase in energy dissipated at the moment of the collision.

- •

- The coefficient of restitution of the collision ranged from 0.04 to 0.07, indicating an almost completely plastic nature of the collision. This means that nearly all of the kinetic energy was transformed into deformation and heat energy, with only a marginal portion recovered after rebounding.

- •

- At higher speeds, a decrease in acceleration values was observed, which confirms a “softer” course of the collision due to impact with an elastic item (the truck wheel).

- •

- The simulation results can serve as a basis for further research on modelling energy losses in collisions involving different vehicle geometries and structural materials.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Irawan, A.P.; Fitriyana, D.F.; Tezara, C.; Siregar, J.P.; Laksmidewi, D.; Baskara, G.D.; Abdullah, M.Z.; Junid, R.; Hadi, A.E.; Hamdan, M.H.M.; et al. Overview of the Important Factors Influencing the Performance of Eco-Friendly Brake Pads. Polymers 2022, 14, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Świderski, A.; Borucka, A.; Jacyna-Gołda, I.; Szczepański, E. Wear of brake system components in various operating conditions of vehicle in the transport company. Eksploat. Niezawodn. —Maint. Reliab. 2019, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Wang, W.; Zhang, M.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, W. Influence of leakage during cyclic pneumatic braking on the dynamic behavior of heavy-haul trains. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 228, 112490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, M.T.; Kwesi Ampadu, W.-M.; Ksaibati, K. An investigation of brake failure related crashes and injury severity on mountainous roadways in Wyoming. J. Saf. Res. 2023, 84, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yang, X.; Wang, S.; Xiao, J.; Hou, Q. Comprehensive Analysis on the Performance and Material of Automobile Brake Discs. Metals 2020, 10, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günay, M.; Korkmaz, M.E.; Özmen, R. An investigation on braking systems used in railway vehicles. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2020, 23, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borawski, A. Common methods in analysing the tribological properties of brake pads and discs—A review. Acta Mech. Et Autom. 2019, 13, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisanrao, K.N.; Vasava, A.; Sulakhe, V. A comprehensive review on brake pad materials and geometries: Performance, environmental impact, and emerging technologies. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawande, S.H.; Banait, A.S.; Balashowry, K. Study on wear analysis of substitute automotive brake pad materials. Aust. J. Mech. Eng. 2020, 21, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemlik, M.; Dziubek, M.; Pyka, D.; Konta, Ł.; Grygier, D. Case study of accelerated wear of brake discs made of grey cast iron characterized by increased thermal stability. Combust. Engines 2022, 190, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadnejad, A.; Bahrami, A.; Goli, M.; Nia, H.D.; Taheri, P. Wear Induced Failure of Automotive Disc Brakes—A Case Study. Materials 2019, 12, 4214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, F.; Cristescu, A.-C. Experimental Study of the Correlation between the Wear and the Braking System Efficiency of a Vehicle. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemani, M.; Gialanella, S.; Straffelini, G.; Ciudin, R.; Olofsson, U.; Perricone, G.; Metinoz, I. Dry sliding of a low steel friction material against cast iron at different loads: Characterization of the friction layer and wear debris. Wear 2017, 376–377, 1450–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Leonardi, M.; Wahlström, J.; Gialanella, S.; Olofsson, U. Friction, wear and airborne particle emission from Cu-free brake materials. Tribol. Int. 2020, 141, 150959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, F.; Cristescu, A.-C. Tribological Behavior of Friction Materials of a Disk-Brake Pad Braking System Affected by Structural Changes—A Review. Materials 2022, 15, 4745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, L.Y.; Poletto, J.C.; Gehlen, G.S.; Lasch, G.; Neis, P.D.; Ramalho, A.; Ferreira, N.F. Transition in wear regime during braking applications: An analysis of the debris and surfaces of the brake pad and disc. Tribol. Int. 2023, 189, 108968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voloacă, Ş.; Badea-Romero, A.; Badea-Romero, F.; Toma, M.F. Motor Vehicle Brake Pad Wear—A Review. Vehicles 2025, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Gigan, G.; Vernersson, T.; Lundén, R.; Skoglund, P. Disc brakes for heavy vehicles: An experimental study of temperatures and cracks. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2014, 229, 684–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Shen, J.; Wang, X.; Farmilo, N.; Guo, X. Microstructure evolution and tribo-oxidation induced by friction and wear of cast iron brake discs. Surf. Sci. Tech. 2024, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, T.R.; Shanti, E.S.K. A Review on Fabrication of Recent Novel Brake Friction Materials. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. 2023, 12, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A. Overview of Disc Brakes and Related Phenomena—A review. Int. J. Veh. Noise Vib. 2014, 10, 257–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Zhang, J.; Nie, X.; Tjong, J.; Matthews, D.T.A. Wear mechanism evolution on brake discs for reduced wear and particulate emissions. Wear 2020, 452–453, 203283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezuglov, A.; Comert, G. Short-term freeway traffic parameter prediction: Application of grey system theory models. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 62, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoka, K. Predicting economic indices of vehicle insurance using the “grey-system theory”. Sci. J. Silesian Univ. Technol. Ser. Transp. 2020, 107, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, C.S.; Sloan, B.K.; Brizendine, E.J.; Bock, H. An analysis of maximum vehicle G forces and brain injury in motorsports crashes. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2006, 38, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kowalski, S. Simulation of the Influence of Braking System Damage on Vehicle Driving Safety. Eng 2026, 7, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010016

Kowalski S. Simulation of the Influence of Braking System Damage on Vehicle Driving Safety. Eng. 2026; 7(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleKowalski, Sławomir. 2026. "Simulation of the Influence of Braking System Damage on Vehicle Driving Safety" Eng 7, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010016

APA StyleKowalski, S. (2026). Simulation of the Influence of Braking System Damage on Vehicle Driving Safety. Eng, 7(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010016