Innovative Retarders for Controlling the Setting Characteristics of Fly Ash-Slag Geopolymers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Program

2.1. Materials

2.2. Mix Proportion and Sample Preparation

2.3. Test for Setting Time, Workability, and Compressive Strength

3. Results and Discussion

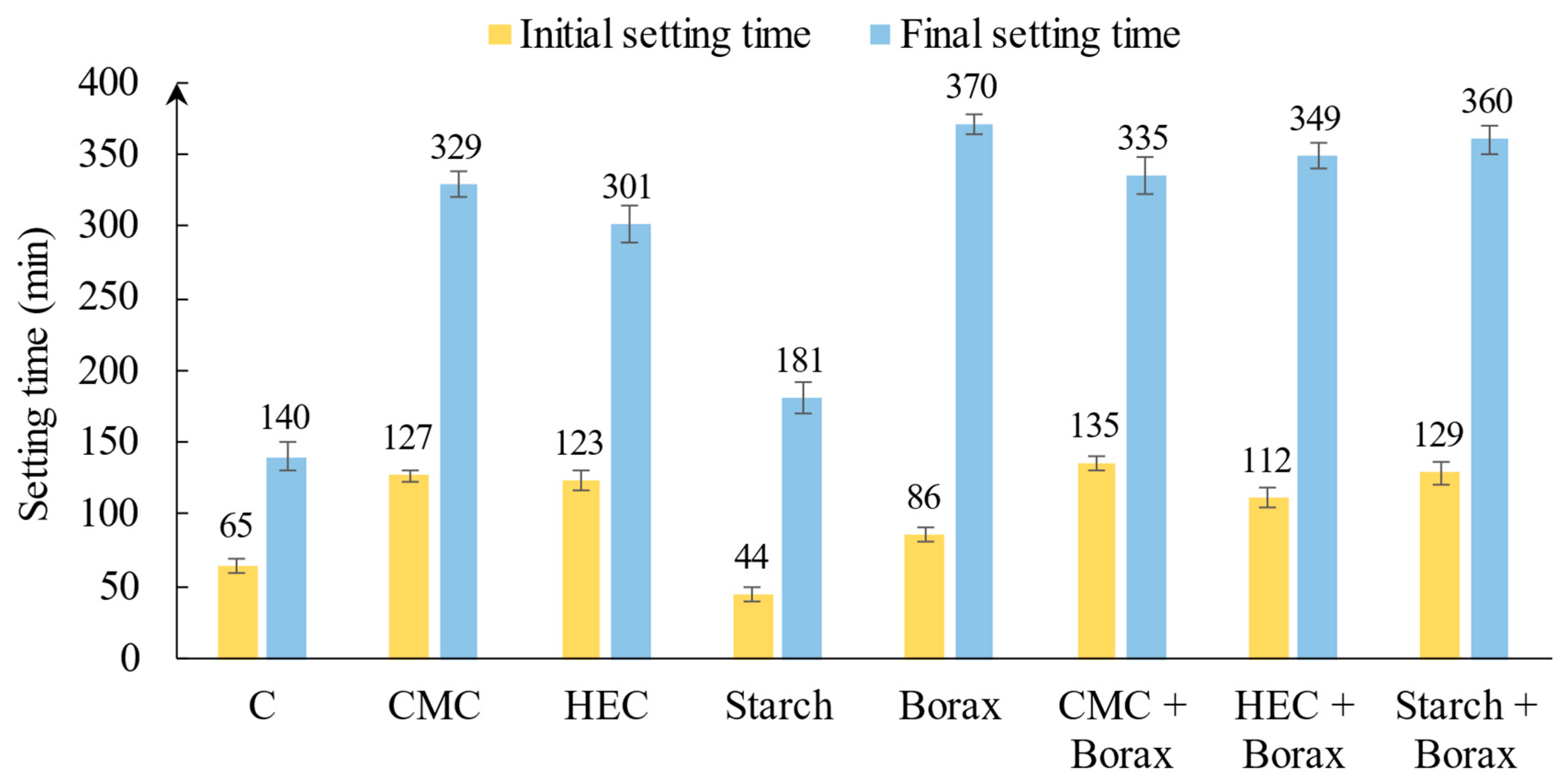

3.1. Setting Time

3.2. Workability

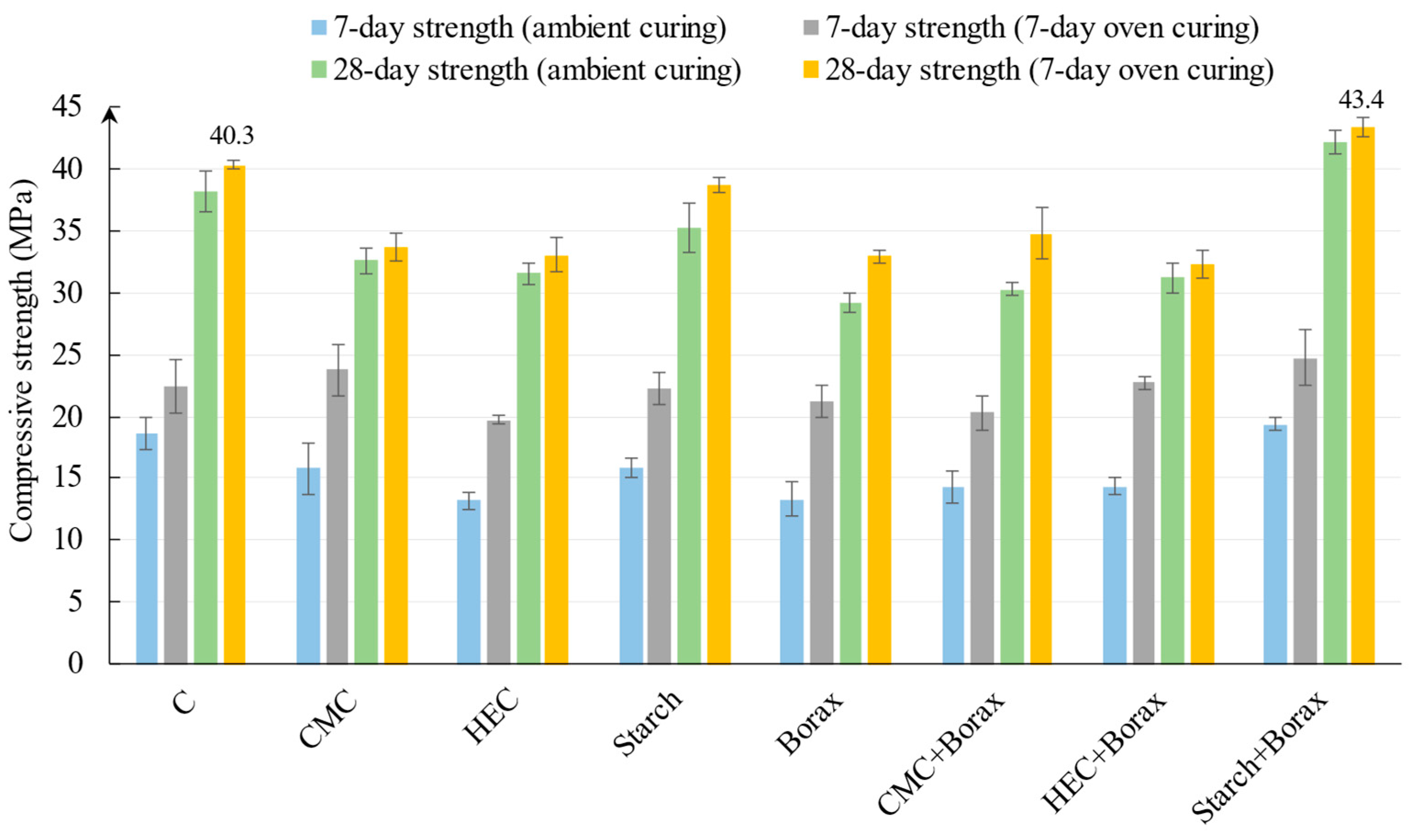

3.3. Compressive Strength

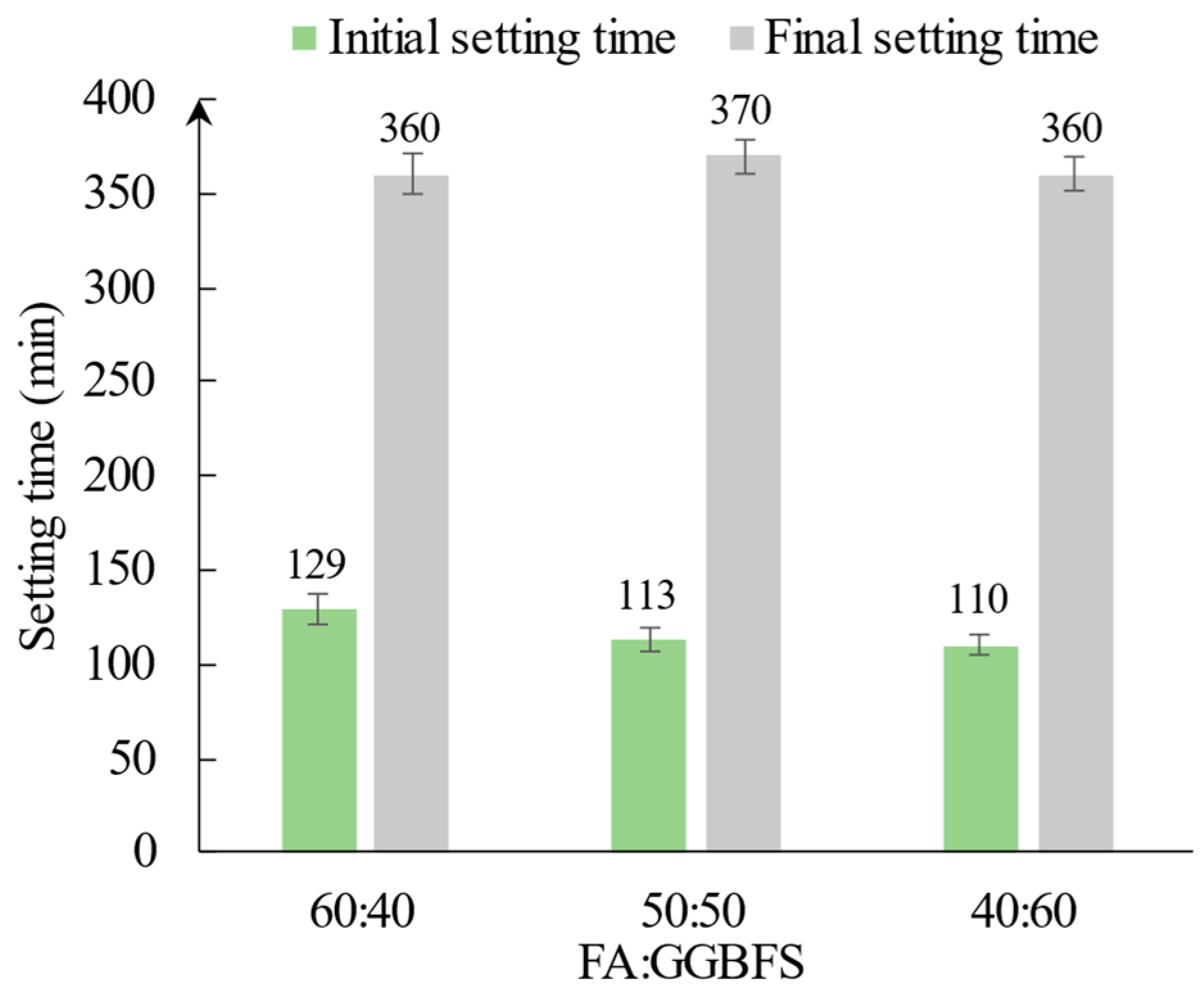

3.4. Compressive Strength of Geopolymer with Varying Binder Proportions

4. Conclusions

- Among the different retarders, CMC, HEC, and a combination of CMC, HEC, and starch with borax were found to be effective in improving the initial and final setting time. Starch was found to be ineffective as a retarder. However, in combination with borax, it improved the initial and final setting times to 129 min and 360 min, respectively, complying with the standards. Cellulose forms a waterproofing barrier that hinders the setting time of the geopolymer. Cellulose/starch with borax shows synergistic effects combining the physical and chemical retardation mechanisms, delaying setting time.

- The compressive strength at 28 days improved for the starch and borax retarder combination compared with the negative effect for all other retarders. Even though starch was ineffective in improving setting time, it did not have a negative effect on compressive strength. The optimum retarder, a combination of starch and borax, has complementary effects that lead to controlled geopolymerization and a complete reaction. The starch and borax as the retarder maintained the compressive strength, even with a slight improvement, indicating that it is effective in improving setting time without negatively impacting strength development.

- The retarders were equally effective from the results of oven-cured specimens compared to ambient-cured ones. For all the oven-cured specimens, a slight improvement in the 28-day strength was obtained; the strength improvement generally observed in FA–GGBFS geopolymers was unaffected by the addition of the retarders. In addition, the retarder worked well for different mix proportions of FA and GGBFS. The retarder works well in calcium-rich geopolymer with aluminosilicate precursors.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ouellet-Plamondon, C.; Habert, G. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Alkali-Activated Cements and Concretes. In Handbook of Alkali-Activated Cements, Mortars and Concretes; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2015; pp. 663–686. [Google Scholar]

- Neupane, K. Evaluation of Environmental Sustainability of One-Part Geopolymer Binder Concrete. Clean. Mater. 2022, 6, 100138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowles, M.; O’Connor, B. Chemical Optimisation of the Compressive Strength of Aluminosilicate Geopolymers Synthesised by Sodium Silicate Activation of Metakaolinite. J. Mater. Chem. 2003, 13, 1161–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Van Deventer, J.S.J. The Geopolymerisation of Alumino-Silicate Minerals. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2000, 59, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strydom, C.A.; Swanepoel, J.C. Utilisation of Fly Ash in a Geopolymeric Material. Appl. Geochem. 2002, 17, 1143–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni; Wijaya, S.W.; Hardjito, D. Factors Affecting the Setting Time of Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer. Mater. Sci. Forum 2016, 841, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattanasak, U.; Pankhet, K.; Chindaprasirt, P. Effect of Chemical Admixtures on Properties of High-Calcium Fly Ash Geopolymer. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2011, 18, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Lee, S.; Chon, C. Setting Behavior and Phase Evolution on Heat Treatment of Metakaolin-Based Geopolymers Containing Calcium Hydroxide. Materials 2022, 15, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilton, R.; Wang, S.; Banthia, N. Use of Polysaccharides as a Rheology Modifying Admixture for Alkali Activated Materials for 3D Printing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 458, 139661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, T.; Ramaswamy, K.P.; Saraswathy, B. Effects of Slag and Superplasticizers on Alkali Activated Geopolymer Paste. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 491, 012042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bong, S.H.; Nematollahi, B.; Nazari, A.; Xia, M.; Sanjayan, J. Efficiency of Different Superplasticizers and Retarders on Properties of “one-Part” Fly Ash-Slag Blended Geopolymers with Different Activators. Materials 2019, 12, 3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamali, M.; Khalifeh, M.; Samarakoon, S.; Salehi, S.; Wu, Y. Effect of Organic Retarders on Fluid-State and Strength Development of Rock-Based Geopolymer; RILEM Bookseries; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; Volume 44, pp. 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toobpeng, N.; Thavorniti, P.; Jiemsirilers, S. Effect of Additives on the Setting Time and Compressive Strength of Activated High-Calcium Fly Ash-Based Geopolymers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 417, 135035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni; Herianto, J.G.; Anastasia, E.; Hardjito, D. Effect of Adding Acid Solution on Setting Time and Compressive Strength of High Calcium Fly Ash Based Geopolymer. AIP Conf. Proc. 2017, 1887, 020042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusbiantoro, A.; Ibrahim, M.S.; Muthusamy, K.; Alias, A. Development of Sucrose and Citric Acid as the Natural Based Admixture for Fly Ash Based Geopolymer. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2013, 17, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.E.; Muhsin Lebba, A.; Sreeja, S.; Ramaswamy, K.P. Effect of Borax in Slag-Fly Ash-Based Alkali Activated Paste. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1237, 012006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni, A.; Wijaya, S.W.; Satria, J.; Sugiarto, A.; Hardjito, D. The Use of Borax in Deterring Flash Setting of High Calcium Fly Ash Based Geopolymer. Mater. Sci. Forum 2016, 857, 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni, A.; Purwantoro, A.A.T.; Suyanto, W.S.P.D.; Hardjito, D. Fresh and Hardened Properties of High Calcium Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer Matrix with High Dosage of Borax. Iran. J. Sci. Technol.-Trans. Civ. Eng. 2020, 44, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Zhang, Z. Control of Setting Time of Fly Ash Geopolymer. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Architectural, Civil and Hydraulic Engineering (ICACHE 2024); Advances in Engineering Research; Atlantis Press International BV: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.-h.; Liu, M.-h. Setting Time and Mechanical Properties of Chemical Admixtures Modified FA/GGBS-Based Engineered Geopolymer Composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 431, 136473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.R.; Ukrainczyk, N.; Defáveri do Carmo e Silva, K.; Eduardo Silva, L.; Koenders, E. Effect of Microcrystalline Cellulose on Geopolymer and Portland Cement Pastes Mechanical Performance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 288, 123053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Hoyos, C.; Cristia, E.; Vázquez, A. Effect of Cellulose Microcrystalline Particles on Properties of Cement Based Composites. Mater. Des. 2013, 51, 810–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Wu, D.; Guo, G.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Qu, E.; Liu, J. Effect of Plant Fiber on Early Properties of Geopolymer. Molecules 2023, 28, 4710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IS 3812 (Part 1); Pulverized Fuel Ash-Specification. Bureau of Indian Standards: New Delhi, India, 2003; pp. 1–10.

- John, S.K.; Cascardi, A.; Nadir, Y.; Aiello, M.A.; Girija, K. A New Artificial Neural Network Model for the Prediction of the Effect of Molar Ratios on Compressive Strength of Fly Ash-Slag Geopolymer Mortar. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IS 4031 (Part 5); Methods of Physical Tests for Hydraulic Cement. Bureau of Indian Standards: New Delhi, India, 1988; pp. 1–2.

- ASTM C1611; Standard Test Method for Slump Flow of Self-Consolidating Concrete. American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2009; pp. 1–6.

- Ishwarya, G.; Singh, B.; Deshwal, S.; Bhattacharyya, S.K. Effect of Sodium Carbonate/Sodium Silicate Activator on the Rheology, Geopolymerization and Strength of Fly Ash/Slag Geopolymer Pastes. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 97, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.; Wang, K.; Fu, C. Shrinkage Behavior of Fly Ash Based Geopolymer Pastes with and without Shrinkage Reducing Admixture. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 98, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematollahi, B.; Sanjayan, J. Effect of Different Superplasticizers and Activator Combinations on Workability and Strength of Fly Ash Based Geopolymer. Mater. Des. 2014, 57, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, S.K.; Nadir, Y.; Cascardi, A.; Arif, M.M.; Girija, K. Effect of Addition of Nanoclay and SBR Latex on Fly Ash-Slag Geopolymer Mortar. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 66, 105875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C873/C873M-10; Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Concrete Cylinders Cast in Place in Cylindrical Molds. American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2010.

- Chen, R.; Ahmari, S.; Zhang, L. Utilization of Sweet Sorghum Fiber to Reinforce Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer. J. Mater. Sci. 2014, 49, 2548–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-majidi, M.H.; Lampropoulos, A.; Cundy, A.; Meikle, S. Development of Geopolymer Mortar Under Ambient Temperature for in situ Applications. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 120, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hassan, H.; Ismail, N. Effect of Process Parameters on the Performance of Fly Ash/GGBS Blended Geopolymer Composites. J. Sustain. Cem. Mater. 2018, 7, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C 191-04; Time of Setting of Hydraulic Cement by Vicat Needle. American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2004; pp. 1–8.

- Ataie, F.F. Influence of Cementitious System Composition on the Retarding Effects of Borax and Zinc Oxide. Materials 2019, 12, 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Qian, C. Effect of Borax on Hydration and Hardening Properties of Magnesium and Pottassium Phosphate Cement Pastes. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. Sci. Ed. 2010, 25, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Yang, Z.; Ou, Z.; Huang, Y.; Qu, F.; Unluer, C.; Li, N. Effect of Borax and Magnesia on Setting, Strength, and Microstructure of Acid-Activated Fly Ash Geopolymers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 498, 144013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, D.; Jia, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, P.; Yu, B. Effects of Mud Content on the Setting Time and Mechanical Properties of Alkali-Activated Slag Mortar. Materials 2023, 16, 3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baba, T.; Tsujimoto, Y. Examination of Calcium Silicate Cements with Low-Viscosity Methyl Cellulose or Hydroxypropyl Cellulose Additive. Biomed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 4583854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spychał, E.; Stępień, P. Effect of Cellulose Ether and Starch Ether on Hydration of Cement Processes and Fresh-State Properties of Cement Mortars. Materials 2022, 15, 8764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partschefeld, S.; Aschoff, J.; Osburg, A. Interaction of PCE and Chemically Modified Starch Admixtures with Metakaolin-Based Geopolymers—The Role of Activator Type and Concentration. Materials 2025, 18, 4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishna, R.S.; Rehman, A.U.; Mishra, J.; Saha, S.; Korniejenko, K.; Rehman, R.U.; Salamci, M.U.; Sglavo, V.M.; Shaikh, F.U.A.; Qureshi, T.S. Additive Manufacturing of Geopolymer Composites for Sustainable Construction: Critical Factors, Advancements, Challenges, and Future Directions; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; Volume 10, ISBN 4096402400. [Google Scholar]

- Pahlawan, T.; Tarigan, J.; Ekaputri, J.J.; Nasution, A. Effect of Borax on Very High Calcium Geopolymer Concrete. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2023, 13, 1387–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.L.; Yap, S.P.; Alengaram, U.J.; Yuen, C.W.; Yeo, J.S.; Mo, K.H. Properties of High Calcium Fly Ash Geopolymer Incorporating Recycled Brick Waste and Borax. Hybrid Adv. 2024, 5, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ji, Y.; Li, J.; Gao, F.; Huang, G. Effect of Retarders on the Early Hydration and Mechanical Properties of Reactivated Cementitious Material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 212, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rożek, P.; Florek, P.; Król, M.; Mozgawa, W. Immobilization of Heavy Metals in Boroaluminosilicate Geopolymers. Materials 2021, 14, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| FA | GGBFS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical properties | BAT fineness (m2/kg) | 365 | 382 |

| Specific gravity (g/cc) | 2.97 | 2.91 | |

| Mean particle size (µm) | 24 | 15 | |

| Chemical composition (wt.%) | SiO2 | 61.53 | 33.81 |

| Al2O3 | 25.19 | 19.52 | |

| Fe2O3 | 5.39 | 0.49 | |

| CaO | 1.31 | 35.22 | |

| MgO | 0.63 | 6.68 | |

| SO3 | 0.82 | 1.4 | |

| Na2O | 0.39 | 0.34 | |

| TiO2 | 0.65 | 0.94 | |

| MnO | 0.3 | - | |

| K2O | 0.23 | 0.44 | |

| LOI * | 0.95 | 0.11 |

| Retarder | Quantity (kg/m3) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Geopolymer Paste | Geopolymer Mortar | ||

| Carboxymethyl cellulose | CMC powder | 40 | 19 |

| Water | 40 | 19 | |

| Hydroxyethyl cellulose | HEC powder | 40 | 19 |

| Water | 40 | 19 | |

| Starch | Starch powder | 40 | 19 |

| Water | 40 | 19 | |

| Borax | - | 40 | 19 |

| Hydroxyethyl cellulose + borax | HEC powder | 20 | 9.5 |

| Water | 20 | 9.5 | |

| Borax | 20 | 9.5 | |

| Starch + borax | Starch powder | 20 | 9.5 |

| Water | 20 | 9.5 | |

| Borax | 20 | 9.5 | |

| Carboxymethyl cellulose + borax | CMC powder | 20 | 9.5 |

| Water | 20 | 9.5 | |

| Borax | 20 | 9.5 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

John, S.K.; Cascardi, A.; Nandana, M.; Kurian, F.; Fathima, N.A.; Arif, M.M.; Nadir, Y. Innovative Retarders for Controlling the Setting Characteristics of Fly Ash-Slag Geopolymers. Eng 2025, 6, 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120366

John SK, Cascardi A, Nandana M, Kurian F, Fathima NA, Arif MM, Nadir Y. Innovative Retarders for Controlling the Setting Characteristics of Fly Ash-Slag Geopolymers. Eng. 2025; 6(12):366. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120366

Chicago/Turabian StyleJohn, Shaise Kurialanickal, Alessio Cascardi, Madapurakkal Nandana, Femin Kurian, Niyas Aruna Fathima, M. Muhammed Arif, and Yashida Nadir. 2025. "Innovative Retarders for Controlling the Setting Characteristics of Fly Ash-Slag Geopolymers" Eng 6, no. 12: 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120366

APA StyleJohn, S. K., Cascardi, A., Nandana, M., Kurian, F., Fathima, N. A., Arif, M. M., & Nadir, Y. (2025). Innovative Retarders for Controlling the Setting Characteristics of Fly Ash-Slag Geopolymers. Eng, 6(12), 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120366