Dynamics of a Wind-Driven Lotka–Volterra Amensalism System with Non-Selective Harvesting: Theoretical Analysis and Ecological Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

- How do different wind speeds alter the existence and stability of the system’s equilibrium states?

- 2.

- Do critical wind speeds exist that trigger regime shifts (e.g., from extinction to coexistence)?

- 3.

- Under what conditions does wind promote biodiversity?

2. Model Formulation

- Species 1 () is a commercially valuable, demersal fish species (e.g., similar to Atlantic cod, Gadus morhua), which is often highly vulnerable to bottom trawling ( is high).

- Species 2 () is a benthic invertebrate or a less valuable forage fish (e.g., similar to the sand lance, Ammodytes spp.), which is less susceptible to the primary fishing gear ( is lower). Species 2 inhibits Species 1 through amensalism, potentially via resource preemption of benthic habitat or through mild chemical interference.

2.1. Modeling of Wind Impact Mechanism

2.1.1. Wind Effect on Amensalism

- is the wind speed, the key environmental parameter,

- is the basic amensalism coefficient under windless conditions,

- is the wind mixing effect coefficient, reflecting the degree to which wind promotes the diffusion of inhibitory substances.

- , where the amensalism intensity is maintained when there is no wind.

- , where the amensalism effect monotonically decreases with increasing wind speed.

- , where the amensalism effect tends to disappear under strong wind conditions.

2.1.2. Wind Effect on Harvesting Effort

- is the theoretical maximum harvesting effort, reflecting the development potential of fishery resources,

- is the wind resistance coefficient, characterizing the degree to which wind conditions constrain fishing operations.

- , which shows reaching maximum harvesting effort when there is no wind.

- , which shows exponential decay with increasing wind speed.

- , which shows fishing activities completely cease under extreme wind conditions.

2.2. Complete Wind-Harvesting-Population Coupled Model

- The model describes the dynamic evolution of an amensalism system under harvesting pressure regulated by the wind environment.

- Wind speed W, as a key environmental parameter, simultaneously affects interspecific interactions and human harvesting activities.

- The system reflects the compound effects of natural factors (wind) and anthropogenic factors (harvesting) on the marine ecosystem.

3. Existence Analysis of Equilibrium Points

3.1. Trivial Equilibrium Point

- Ecological significance: represents the state where both species are extinct, which may be caused by overharvesting or harsh environmental conditions.

3.2. Boundary Equilibrium Point

- Ecological significance: represents the state where species 2 is extinct while species 1 survives. The existence condition requires that the intrinsic growth rate of species 1 is sufficiently large to overcome the harvesting pressure.

3.3. Boundary Equilibrium Point

- Ecological significance: represents the state where species 1 is extinct, while species 2 survives. The existence condition requires that the intrinsic growth rate of species 2 can resist the harvesting pressure.

3.4. Positive Equilibrium Point

- 1.

- (ensures )

- 2.

- (ensures )

- Ecological significance: represents the state where both species coexist. The existence conditions require the following:

- Species 2 can overcome harvesting pressure ().

- Species 1 can maintain a positive population after suffering harvesting pressure and amensalism from species 2 (second inequality).

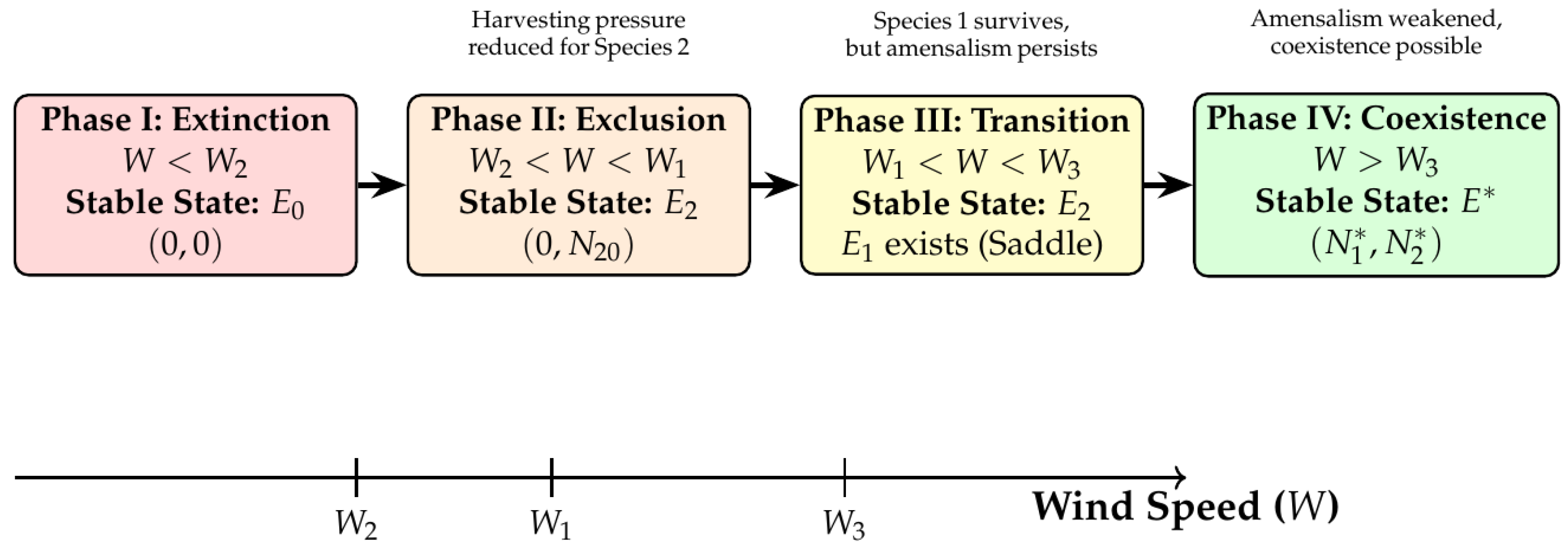

3.5. Effect of Wind Speed on Equilibrium Existence

- when , exists,

- when , exists,

- when , exists.

- Ecological interpretation: As wind speed increases, the effective harvesting effort decreases and the amensalism coefficient decreases, making the equilibrium existence conditions easier to satisfy. This indicates that appropriate wind speed is beneficial for population survival and coexistence.

4. Local Stability Analysis of Equilibrium Points

4.1. Local Stability of Trivial Equilibrium Point

- 1.

- If and , then is a locally asymptotically stable node;

- 2.

- If or , then is an unstable node.

- Ecological significance: When harvesting pressure is sufficiently large (), both species cannot sustain their populations, and the system tends to the extinction state .

4.2. Local Stability of Boundary Equilibrium Point

- 1.

- If , then is a locally asymptotically stable node;

- 2.

- If , then is a saddle point (unstable);

- Ecological significance: The stability of depends on whether species 2 can invade. When the growth rate of species 2 is less than its harvesting mortality rate, it cannot invade, and is stable; otherwise, species 2 can invade, and is unstable.

4.3. Local Stability of Boundary Equilibrium Point

- 1.

- If , then is a locally asymptotically stable node;

- 2.

- If , then is a saddle point (unstable).

- Ecological significance: The stability of depends on whether species 1 can invade. The condition indicates that species 1 cannot grow after suffering amensalism and harvesting pressure.

4.4. Local Stability of Positive Equilibrium Point

- Ecological significance: Once the two species reach the coexistence state , the system remains stable, and small disturbances will not disrupt the coexistence pattern.

4.5. Effect of Wind Speed on Local Stability

5. Global Stability Analysis of Equilibrium Points

5.1. Global Stability of Trivial Equilibrium Point

- Ecological significance: When harvesting pressure is sufficiently large such that the intrinsic growth rates of both species cannot overcome their harvesting mortality rates, regardless of the initial population densities, the system will eventually tend toward extinction.

5.2. Global Stability of Boundary Equilibrium Point

- 1.

- ( exists);

- 2.

- (species 2 cannot grow).

- Ecological significance: Theorem 11 reveals how asymmetric vulnerability to harvesting can determine ecosystem outcomes in an amensal system. Here, species 2’s inability to withstand fishing pressure () leads to its extinction, while species 1 persists not by outcompeting species 2 but simply by being more resilient to the shared anthropogenic pressure. The amensal relationship becomes irrelevant when species 2 is eliminated by fishing alone.

5.3. Global Stability of Boundary Equilibrium Point

- 1.

- ( exists);

- 2.

- (species 1 cannot grow).

- Ecological significance: This theorem captures the essential character of amensalism—the uninhibited species (species 2) dominates not by competitive superiority but by persistently suppressing the other species while remaining unaffected itself. The condition shows how amensalism synergistically amplifies harvesting pressure on species 1, creating a double burden that drives it to extinction. Species 2 thrives simply by being both resistant to harvesting and free from reciprocal negative effects.

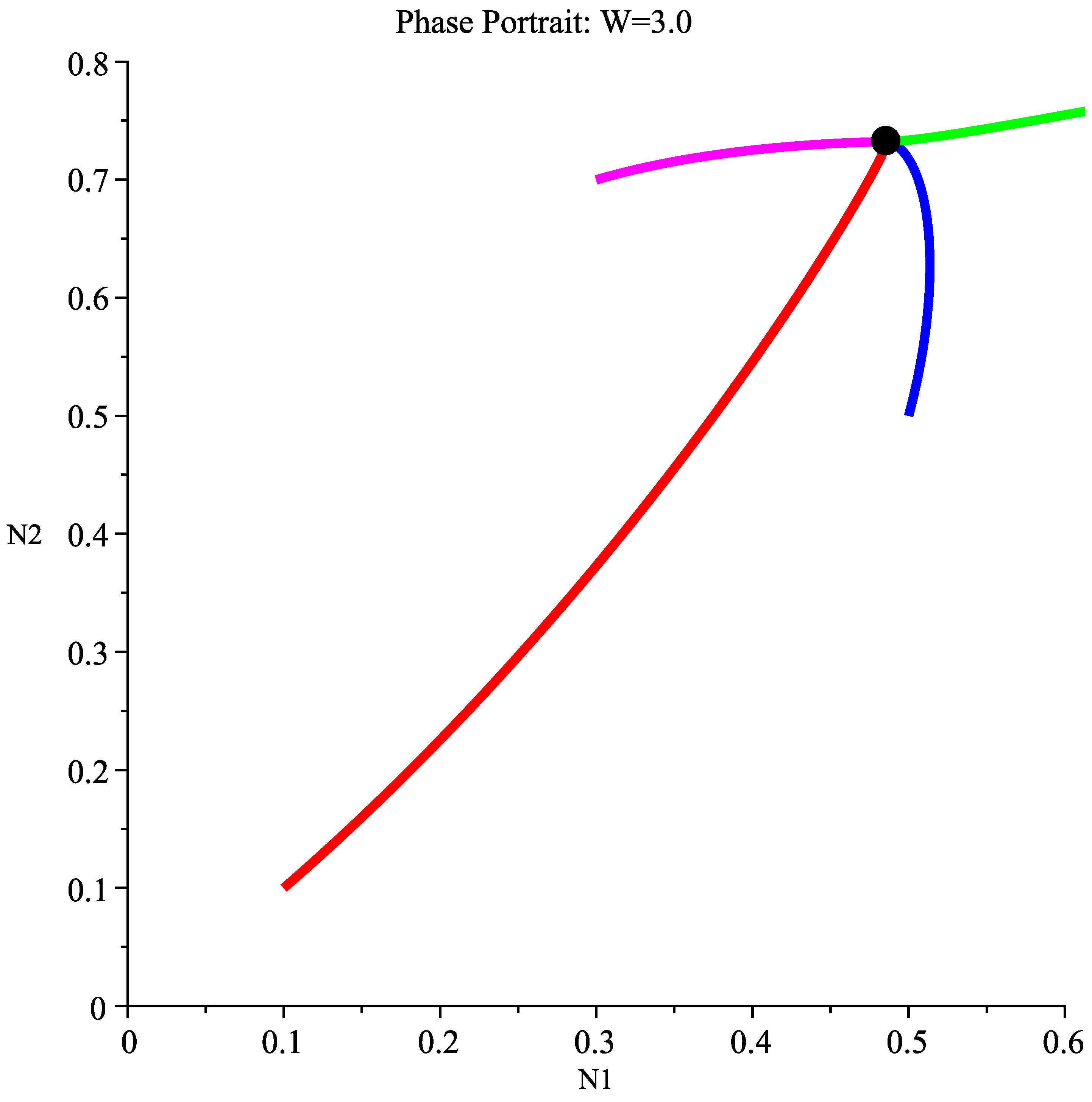

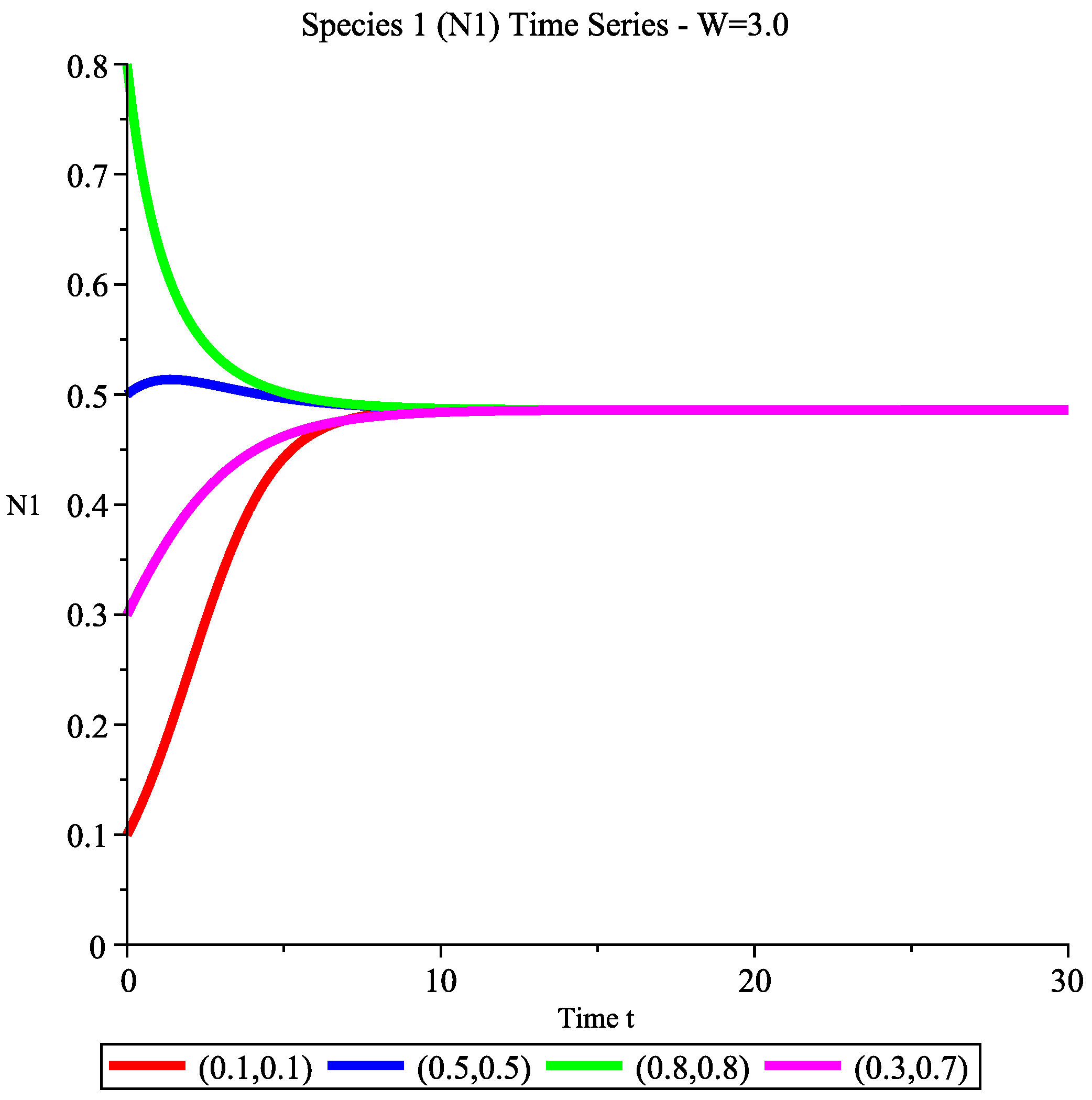

5.4. Global Stability of Positive Equilibrium Point

- Ecological significance: Theorem 13 demonstrates the remarkable situation where environmental conditions (wind) can neutralize amensalism to enable coexistence. As wind speed increases, it simultaneously weakens the amensal effect ( decreases) and reduces harvesting pressure ( decreases), thereby alleviating both the biological and anthropogenic stresses on species 1. This allows both species to persist despite the inherent asymmetry in their interaction.

6. Numerical Examples and Simulation Analysis

6.1. Parameter Setup and Critical Wind Speed Calculation

- : Species 2 begins to survive.

- : Species 1 begins to survive.

- : Both species begin stable coexistence.

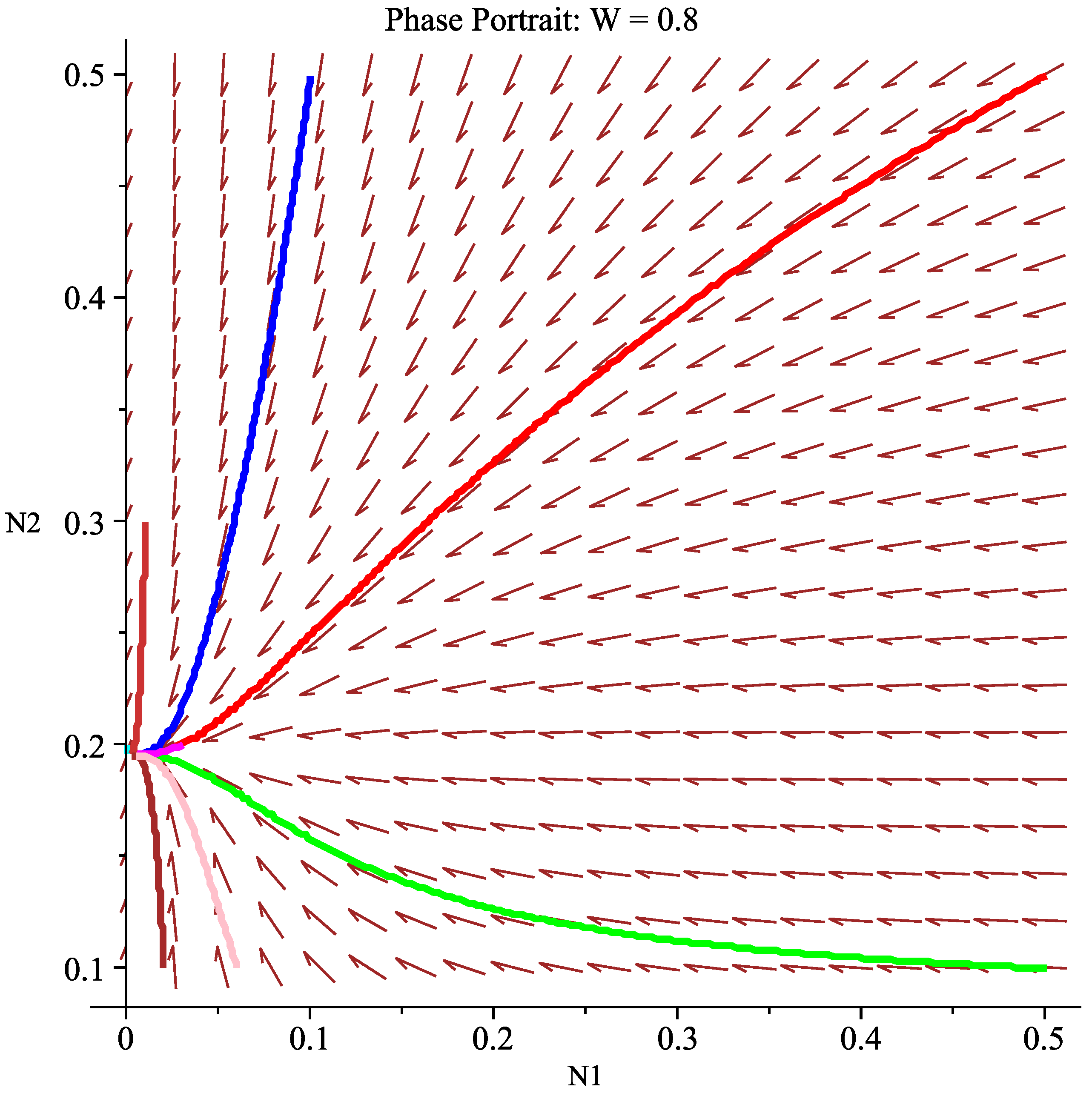

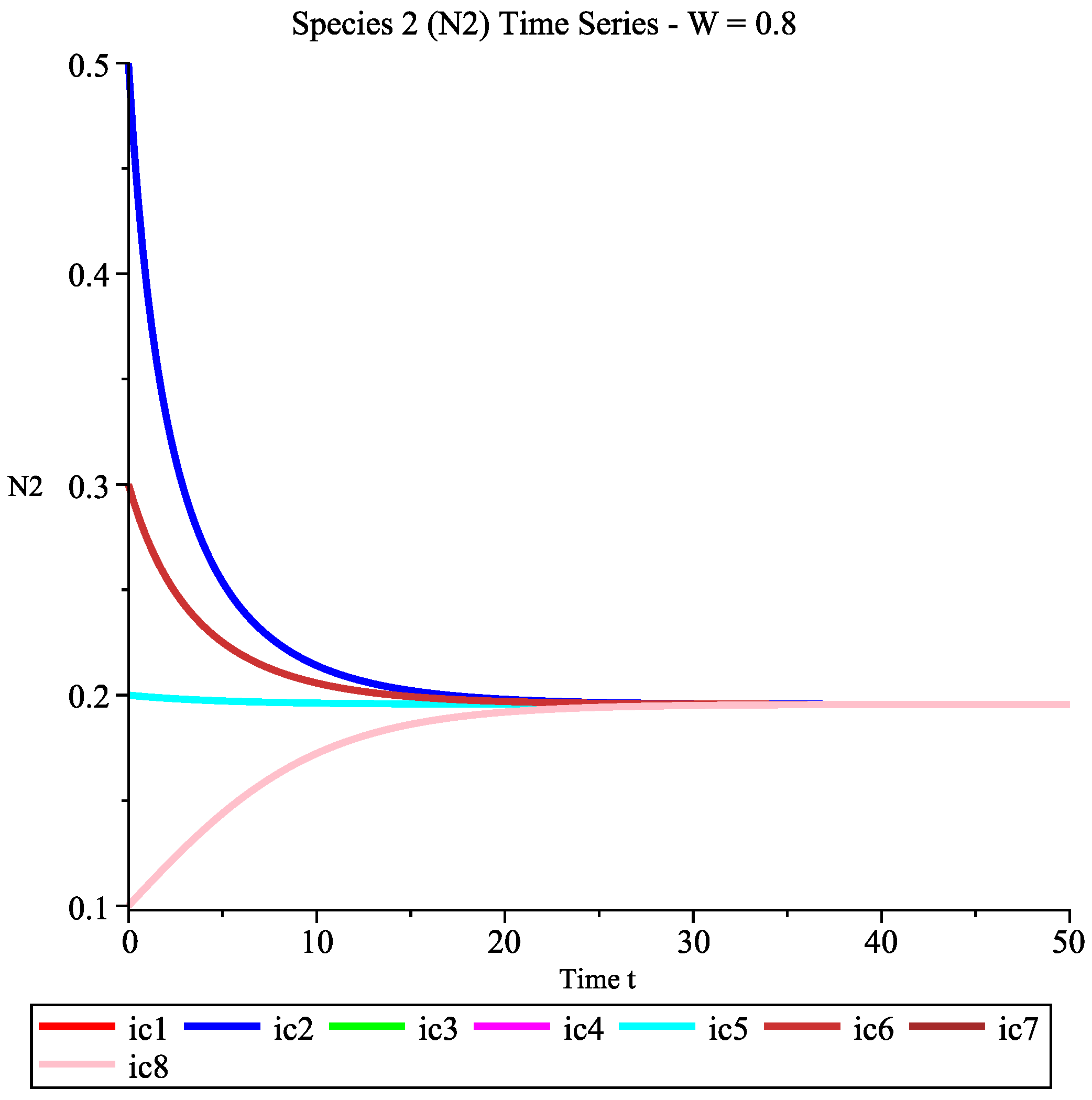

6.2. Dynamic Simulations in Different Wind Speed Intervals

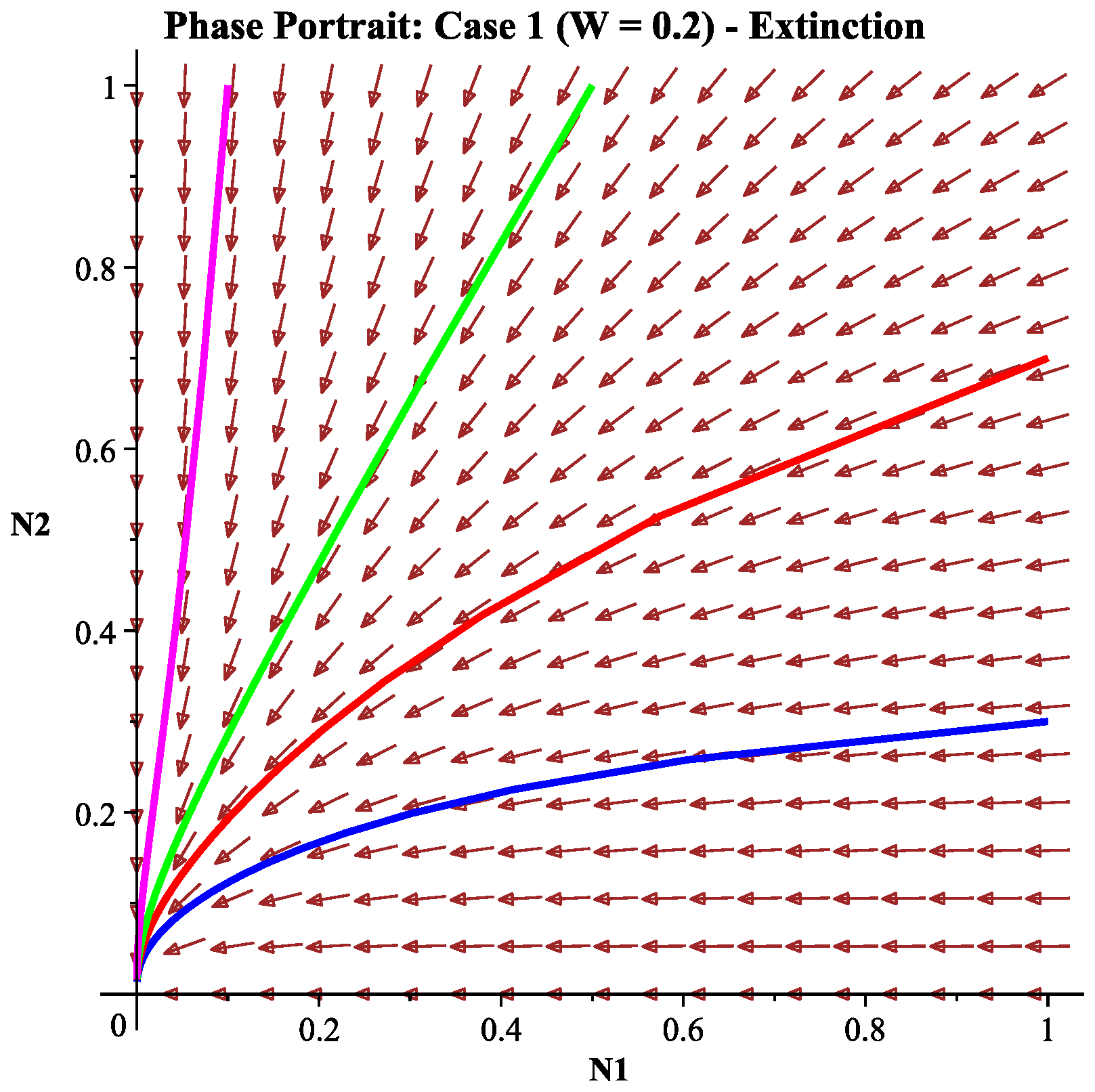

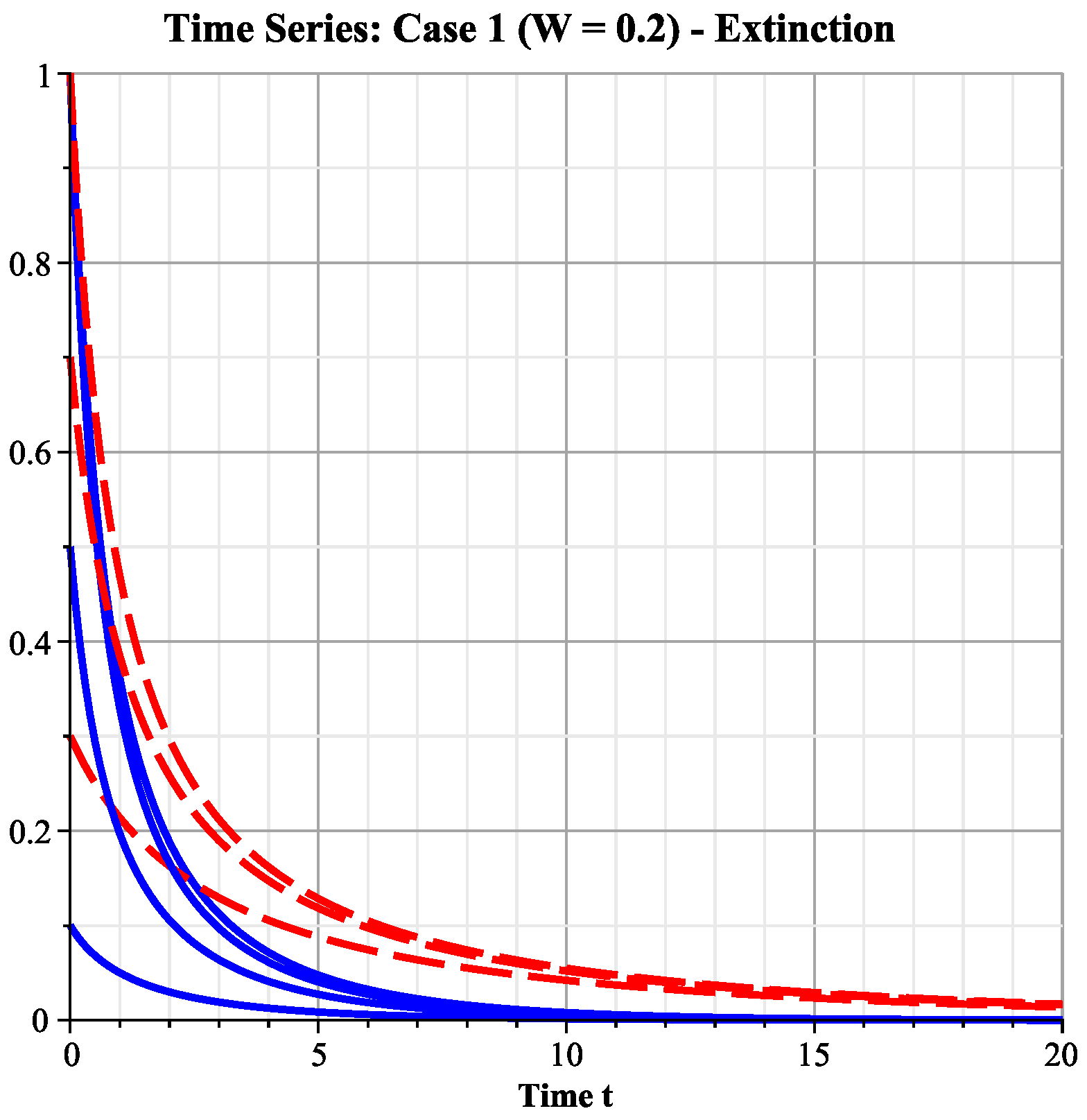

6.2.1. Case 1: Low Wind Speed Interval

- Ecological interpretation: Under low-wind-speed conditions, the effective harvesting effort remains high, and the intrinsic growth rates of both species cannot overcome their harvesting mortality rates, leading the system to eventually approach the extinction of both species. This simulates the ecological disaster scenario of overharvesting.

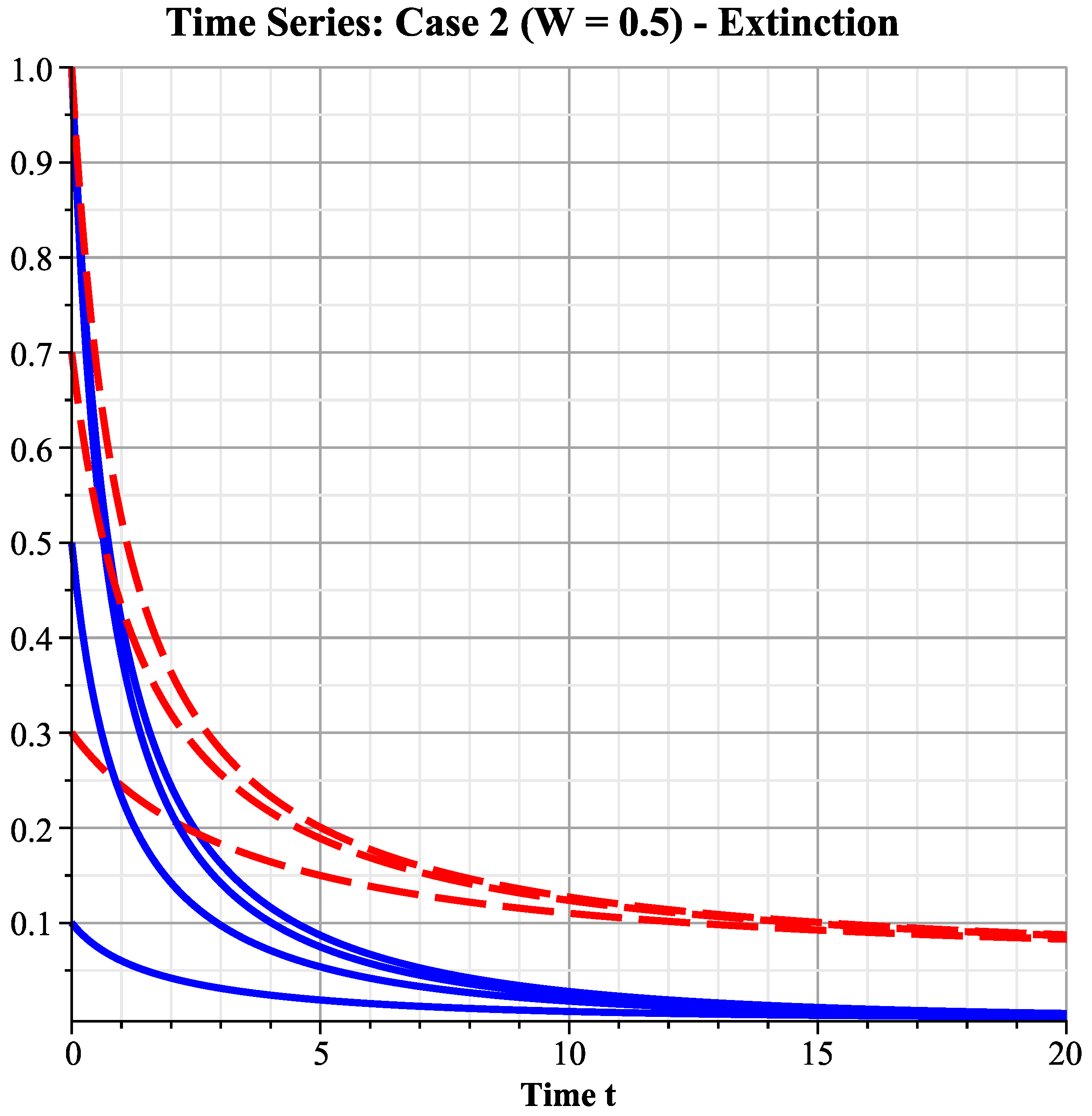

6.2.2. Case 2: Medium Wind Speed Interval

- ( exists).

- ( does not exist since ).

- Ecological interpretation: The increase in wind speed reduces harvesting effort, allowing species 2 (with catchability coefficient less than species 1’s ), which is relatively less vulnerable to harvesting, to first break through the survival threshold, survive, and establish a population. Species 1, suffering greater harvesting pressure, still becomes extinct. The system is in the state of species 2 exclusivity, perfectly verifying that under the scenario, the system first enters this intermediate transition phase as wind speed increases.

6.2.3. Case 3: Intermediate Wind Speed Interval

- Ecological interpretation: Ecologically, this intermediate wind regime represents a critical transition phase. Although species 1 possesses sufficient growth rate to overcome harvesting pressure in isolation (), the persistent amensalistic effect from species 2 () prevents stable coexistence. The system therefore converges to exclusive dominance by species 2, confirming the theoretical framework established in Section 4.5 for the parameter regime where .

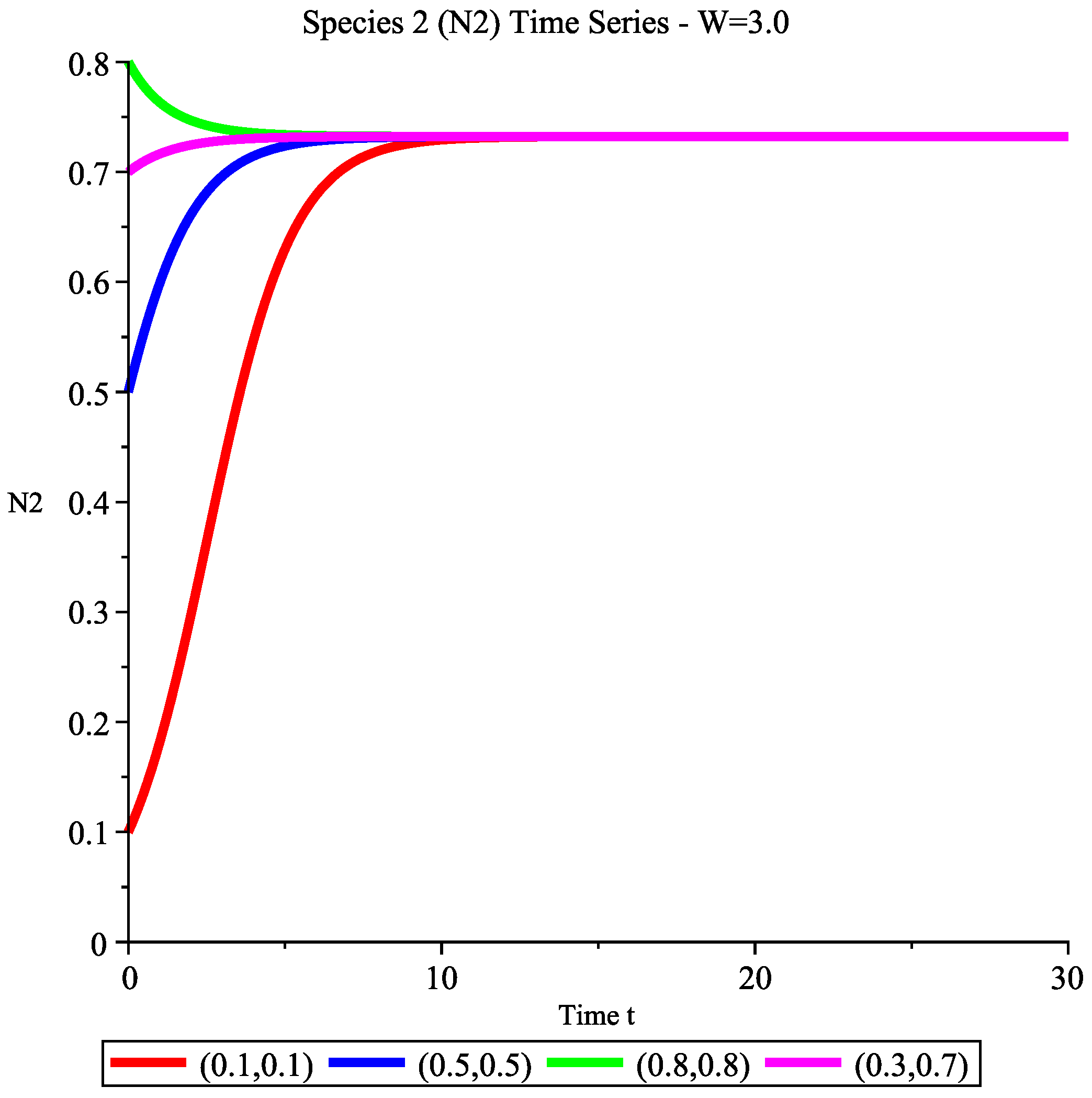

6.2.4. Case 4: High Wind Speed Interval

6.3. Management Implications and Discussion

- 1.

- Identification and application of critical wind speeds: For specific sea areas, the critical wind speed for ecological recovery can be determined by estimating model parameters. When forecasted wind speeds are consistently below , fishery management alerts should be triggered.

- 2.

- Adaptive harvesting management: During low-wind-speed seasons (), fishery management departments should proactively reduce harvesting effort (e.g., decrease fishing vessel operation days) to simulate the ecological effects of high wind speeds and assist population recovery.

- 3.

- Marine protected area planning: When formulating marine protected area plans, priority should be given to sea areas with favorable wind conditions (i.e., higher average wind speeds) or areas located in wind channels, utilizing natural wind power to promote biodiversity within protected areas.

- 4.

- Wind as an ecological restoration tool: This study theoretically demonstrates that wind is a natural force that can promote ecological recovery. When conditions permit, even artificial interventions to enhance local mixing (simulating wind effects) could be considered as auxiliary means for restoring degraded ecosystems.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D

Appendix E

- If and , i.e., and , then is a stable node;

- If or , i.e., or , then is an unstable node.

Appendix F

- If , i.e., , then both eigenvalues are negative, and is a stable node;

- If , i.e., , then one eigenvalue is negative and one positive, and is a saddle point (unstable).

Appendix G

- If , i.e., , then both eigenvalues are negative, and is a stable node;

- If , i.e., , then one eigenvalue is positive and one negative, and is a saddle point (unstable).

Appendix H

Appendix I

Appendix J

- 1.

- ;

- 2.

- For any , ;

- 3.

- is radially unbounded.

Appendix K

- ;

- For any , since the function (equality holds if and only if ), and , we have ;

- V is radially unbounded, i.e., when , .

- 1.

- (obviously holds);

- 2.

- .

Appendix L

- ;

- For any , since the function (equality holds if and only if ), and , we have ;

- V is radially unbounded, i.e., when , .

- 1.

- (obviously holds);

- 2.

- .

Appendix M

- ;

- For any , since the function (equality holds if and only if ), we have ;

- V is radially unbounded.

- 1.

- (obviously holds);

- 2.

- .

References

- Xi, X.; Griffin, J.N.; Sun, S. Grasshoppers amensalistically suppress caterpillar performance and enhance plant biomass in an alpine meadow. Oikos 2013, 122, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimoto, S. Coexistence and weak amensalism of congeneric gall-forming aphids on the Japanese elm. Popul. Ecol. 1995, 37, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osakabe, M.; Hongo, K.; Funayama, K.; Osumi, S. Amensalism via webs causes unidirectional shifts of dominance in spider mite communities. Oecologia 2006, 150, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pommier, S.; Strehaiano, P.; Delia, M.L. Modelling the growth dynamics of interacting mixed cultures: A case of amensalism. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2005, 100, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, H.M.; Huyvaert, K.P.; Hodum, P.J.; Anderson, D.J. Nesting distributions of Galapagos boobies (Aves: Sulidae): An apparent case of amensalism. Oecologia 2002, 132, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P. Dynamics of microbial competition, commensalism, and cooperation and its implications for coculture and microbiome engineering. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2021, 118, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dairain, A.; Gonzalez, P.; Legeay, A.; Maire, O.; Daffe, G.; Pascal, L.; de Montaudouin, X. Parasite interactions in the bioturbator Upogebia pusilla (Decapoda: Gebiidae): A case of amensalism? Mar. Biol. 2017, 164, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C.; Rendueles, M.; Diaz, M. Microbial amensalism in Lactobacillus casei and Pseudomonas taetrolens mixed culture. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2017, 40, 1111–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, X.H.; Wang, B.B.; Zhang, H.L. Stability analysis on the dynamic model of fish swarm amensalism. Adv. Appl. Math. 2016, 5, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.G. Dynamic behaviors of a non-selective harvesting Lotka-Volterra amensalism model incorporating partial closure for the populations. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018, 2018, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.Y.; Chen, F.D. Dynamical analysis of a two species amensalism model with Beddington–DeAngelis functional response and Allee effect on the second species. Nonlinear Anal. Real World Appl. 2019, 48, 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Y.; Hou, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, F. The influence of fear effect to the dynamic behaviors of Lotka-Volterra ammensalism model. Eng. Lett. 2024, 32, 1233–1242. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Li, Q.; Chen, F. Dynamic behaviors of a two species amensalism model with a second species dependent cover. Eng. Lett. 2024, 32, 1553–1561. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, Y.; Chen, F. Global stability, bifurcations and chaos control in a discrete amensalism model with cover and saturation effect. J. Appl. Anal. Comput. 2025, 15, 2977–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, J.M.; González-Megías, A. Asymmetrical interactions between ungulates and phytophagous insects: Being different matters. Ecology 2002, 83, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Alhadi, A.R.S.; Naji, R.K. The contribution of amensalism and parasitism in the three-species ecological system’s dynamic. Commun. Math. Biol. Neurosci. 2024, 2024, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Abd Alhadi, A.R.S.; Naji, R.K. The role of amensalism and parasitism on the dynamics of three species ecological system. Results Control Optim. 2025, 19, 100571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Deng, H. The qualitative analysis of a two species ammenslism model with non-monotonic functional response and Allee effect on second species. Ann. Appl. Math. 2019, 35, 126–138. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Wang, Q. Bifurcation analysis for two-species commensalism (amensalism) systems with distributed delays. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2022, 32, 2250133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.Y.; Wang, Q.R. Stability and Hopf bifurcation analysis for a two species commensalism system with delay. Qual. Theory Dyn. Syst. 2021, 20, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Wang, Q. Global dynamics of a Beddington–DeAngelis amensalism system with weak Allee effect on the first species. Appl. Math. Comput. 2021, 408, 126368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.M.; Wang, Q.R. Global dynamics of a Holling-II amensalism system with nonlinear growth rate and Allee effect on the first species. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2021, 31, 2150050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Qiu, Y. Global dynamics of a Holling-II amensalism system with a strong Allee effect on the harmful species. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2024, 34, 2450115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Du, Y.F. Stability and bifurcation analysis of an amensalism system with Allee effect. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2020, 2020, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Ma, Y.; Du, Y. Global dynamics of an amensalism system with Michaelis-Menten type harvesting. Electron. Res. Arch. 2022, 31, 549–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Y.; Yu, H.G.; Dai, C.J.; Ma, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, M. Dynamical analysis of an aquatic amensalism model with non-selective harvesting and Allee effect. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2021, 18, 8857–8882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Xia, Y.H.; Zhang, T.H. Stability and bifurcation analysis of an amensalism model with weak Allee effect. Qual. Theory Dyn. Syst. 2020, 19, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, C.Q. Dynamic behaviors of a stage structure amensalism system with a cover for the first species. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018, 2018, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Huang, X.Y.; Deng, H. Stability and bifurcation analysis of two species amensalism model with Michaelis-Menten type harvesting and a cover for the first species. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018, 2018, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.D.; Chen, F.D.; He, M.X. Dynamic behaviors of two species amensalism model with a cover for the first species. J. Math. Comput. Sci. 2016, 16, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.F. Bifurcated periodic solutions in an amensalism system with strong generic delay kernel. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2013, 36, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Stability and bifurcation analysis for a amensalism system with delays. Math. Numer. Sin. 2008, 30, 213–224. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, R.X.; Zhao, L.; Lin, Q.X. Stability analysis of a two species amensalism model with Holling II functional response and a cover for the first species. J. Nonlinear Funct. Anal. 2016, 2016, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, R. Dynamic behaviors of a nonlinear amensalism model. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018, 2018, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R. A two species amensalism model with non-monotonic functional response. Commun. Math. Biol. Neurosci. 2016, 2016, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Ding, L.; Hui, Y.; Song, X. Dynamics of an amensalism system with strong Allee effect and nonlinear growth rate in deterministic and fluctuating environment. Nonlinear Dyn. 2024, 112, 21389–21408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Chen, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, F. Dynamic analysis of a discrete amensalism model with Allee effect. J. Appl. Anal. Comput. 2023, 13, 2416–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Chen, F.; Lin, S. Complex dynamics analysis of a discrete amensalism system with a cover for the first species. Axioms 2022, 11, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Chen, F. Dynamical analysis of a discrete amensalism system with the Beddington–DeAngelis functional response and Allee effect for the unaffected species. Qual. Theory Dyn. Syst. 2023, 22, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Chen, F.; Li, Z.; Chen, L. Global dynamics of two-species amensalism model with Beddington–DeAngelis functional response and fear effect. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2024, 34, 2450075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Huang, Y.; He, G. Stability and bifurcation in Lotka-Volterra amensalism model with saturated wind effect. Eng. Lett. 2025, 33, 2620–2633. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, S.; Cai, Z.; Chen, F. Dynamic behaviors of a two-species amensalism model with wind-dependent refuge. Eng. Lett. 2025, 33, 2885–2895. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; He, G.; Chen, F. Dynamic effects of fear-dependent refuge and fear effects on Lotka-Volterra amensalism model. Eng. Lett. 2025, 33, 2574–2588. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, F.; Chen, L.; Li, Z. Dynamic analysis of an amensalism model driven by multiple factors: The interwoven impacts of refuge, the fear effect, and the Allee effect. Axioms 2025, 14, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Kashyap, A.J.; Zhu, Q.; Chen, F. Dynamical behaviours of discrete amensalism system with fear effects on first species. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2022, 22, 832–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Chen, F.; Chen, L.; Li, Z. Dynamical analysis of a discrete amensalism system with the Beddington-DeAngelis functional response and fear effect. J. Appl. Anal. Comput. 2025, 15, 2089–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Chen, F.; Chen, L.; Li, Z. Dynamical analysis of a discrete amensalism system with Michaelis–Menten type harvesting for the second species. Qual. Theory Dyn. Syst. 2024, 23, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, H.; Chen, F. Bifurcation analysis of a discrete amensalism model. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2024, 34, 2450020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditta, A.; Naik, P.A.; Ahmed, R.; Huang, Z. Exploring periodic behavior and dynamical analysis in a harvested discrete-time commensalism system. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2025, 13, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mougi, A. The roles of amensalistic and commensalistic interactions in large ecological network stability. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Callejas, D.; Molowny-Horas, R.; Araujo, M.B. The effect of multiple biotic interaction types on species persistence. Ecology 2018, 99, 2327–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, M. Global stability and bifurcation analysis of a holling type ii amensalism model with harvesting: An optimal control approach. SSRN 2023, 4489846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.K. Dynamical study and optimal harvesting of a two-species amensalism model incorporating nonlinear harvesting. Appl. Appl. Math. 2022, 18, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Liu, M. Dynamicl analysis of an amensalism system with the implusive harvesting. Adv. Differ. Equ. Control Process. 2021, 25, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Dynamic behaviors of an amensalism system with density dependent birth rate. J. Nonlinear Funct. Anal. 2018, 2018, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambabu, B.S.; Narayan, K.L. A two species amensalism model with a linearly varying cover on the first species. Res. J. Sci. Technol. 2017, 9, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Zhou, X. On the existence of positive periodic solution of a amensalism model with Holling II functional response. Commun. Math. Biol. Neurosci. 2017, 2017, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sita Rambabu, B.; Narayan, K.L.; Bathul, S. A mathematical study of two species amensalism model with a cover for the first species by homotopy analysis method. Adv. Appl. Sci. Res. 2012, 3, 1821–1826. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, K.; Das, S.; Kar, T.K. On non-selective harvesting of a multispecies fishery incorporating partial closure for the populations. Appl. Math. Comput. 2013, 221, 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, A.; Lei, C. Dynamic behaviors of a non-selective harvesting single species stage-structured system incorporating partial closure for the populations. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018, 2018, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, C. Dynamic behaviors of a non-selective harvesting May cooperative system incorporating partial closure for the populations. Commun. Math. Biol. Neurosci. 2018, 2018, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Breen, M.; Graham, N.; Pol, M.; He, P.; Reid, D.; Suuronen, P. Selective fishing and balanced harvesting. Fish. Res. 2016, 184, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, T.K.; Chaudhuri, K.S. On non-selective harvesting of a multispecies fishery. Int. J. Math. Educ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 33, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, M.J.; Barton, B.T. Effects of wind on predator-prey interactions. Food Webs 2017, 13, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studd, E.K.; Peers, M.J.L.; Menzies, A.K.; Derbyshire, R.; Majchrzak, Y.N.; Seguin, J.L.; Murray, D.L.; Dantzer, B.; Lane, J.E.; McAdam, A.G.; et al. Behavioural adjustments of predators and prey to wind speed in the boreal forest. Oecologia 2022, 200, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panja, P. Impacts of wind and anti-predator behaviour on predator-prey dynamics: A modelling study. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Math. 2022, 15, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takyi, E.M.; Cooper, K.; Dreher, A.; McCrorey, C. Dynamics of a predator–prey system with wind effect and prey refuge. J. Appl. Nonlinear Dyn. 2023, 12, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, D.; Kumar, V.; Roy, J.; Alam, S. Modeling wind effect and herd behavior in a predator–prey system with spatiotemporal dynamics. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2022, 137, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Chen, F.; Zhu, Q.; Li, Q. How the wind changes the Leslie-Gower predator-prey system? IAENG Int. J. Appl. Math. 2023, 53, 136–144. [Google Scholar]

- Thirthar, A.A.; Jawad, S.; Abbasi, M.A. The modified predator–prey model response to the effects of global warming, wind flow, fear, and hunting cooperation. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2025, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Pal, N. Modelling the wind effect in predator–prey interactions. Math. Comput. Simul. 2025, 232, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, W.D.; Brinkman, T.J.; Leonawicz, M.; Chapin, F.S., III; Kofinas, G.P. Changing daily wind speeds on Alaska’s North Slope: Implications for rural hunting opportunities. Arctic 2013, 66, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Description | Ecological/Biological Meaning | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| State Variables | |||

| , | Population densities | Density of species 1 (affected) and species 2 (inhibitor) at time t. | biomass·area−1 |

| t | Time | – | time |

| Core Parameters | |||

| , | Intrinsic growth rates | Maximum per capita growth rate under ideal conditions. | time−1 |

| , | Environmental carrying capacities | Maximum population size supported by the environment. | biomass·area−1 |

| Basic amensalism coefficient | Intensity of inhibition exerted by species 2 on species 1 under windless conditions. | dimensionless | |

| , | Catchability coefficients | Efficiency of harvesting gear for each species; reflects relative vulnerability. | (effort·time)−1 |

| Maximum harvesting effort | Theoretical maximum level of fishing activity in the absence of wind. | effort | |

| m | Proportion of harvestable population | Management parameter; the fraction of the population open to harvesting ( is protected). | dimensionless |

| W | Wind speed | Key environmental driving variable. | speed (e.g., m·s−1) |

| Wind mixing effect coefficient | Quantifies how effectively wind promotes diffusion and dilution of inhibitory substances. | speed−1 | |

| Wind resistance coefficient | Quantifies the constraining effect of wind on fishing operations. | speed−1 | |

| Derived Functions | |||

| Effective amensalism coefficient | Wind-diluted inhibition intensity: . | dimensionless | |

| Effective harvesting effort | Wind-reduced fishing effort: . | effort | |

| Equilibrium Point | Existence Conditions | Ecological State |

|---|---|---|

| Always exists | Both species extinct | |

| Species 2 extinct, species 1 survives | ||

| Species 1 extinct, species 2 survives | ||

| Both species coexist |

| Stable State | Mathematical Conditions | Ecological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Extinction () | and | Ecological collapse: Harvesting pressure is too severe for either species to survive. This represents a fisheries management failure. |

| Species 1 only () | and | Exclusion by dominance: Species 2 is driven to extinction by overharvesting. Species 1, being less vulnerable or faster growing, dominates the ecosystem. |

| Species 2 only () | and | Exclusion by amensalism: Species 1 is suppressed by the combined effect of amensalism from species 2 and harvesting pressure. Species 2 prevails. |

| Coexistence () | exists | Resilient ecosystem: Wind speed is sufficient to weaken both harvesting and amensalism, allowing both species to persist. This is the biodiversity-positive outcome. |

| Parameter | Value | Ecological Explanation | Biological Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | Intrinsic growth rates | Standardized to 1.0 to focus on the relative effects of harvesting vulnerability and amensalism, assuming moderate and equal reproductive capacity for both species. | |

| 1.0 | Environmental carrying capacities | Standardized to 1.0 to simplify the analysis, representing a normalized environment where population densities are expressed as a proportion of their maximum. | |

| 0.5 | Basic amensalism coefficient | Represents a moderate inhibitory effect of species 2 on species 1, strong enough to influence dynamics but not so overwhelming as to preclude coexistence under favorable conditions. | |

| 1.8 | Catchability coefficient of species 1 | Chosen to be higher than to simulate a species that is more vulnerable to harvesting (e.g., due to larger size, slower movement, or attraction to gear). | |

| 1.5 | Catchability coefficient of species 2 | Chosen to be lower than to simulate a species that is less vulnerable to harvesting (e.g., due to smaller size, behavioral avoidance, or different habitat use). | |

| 1.0 | Maximum harvesting effort | Represents the baseline fishing effort under ideal (windless) conditions, standardized to 1.0. | |

| m | 0.8 | Proportion of harvestable population | Reflects a scenario of high fishing pressure with only 20% of the habitat protected, demonstrating the model’s behavior under significant anthropogenic stress. |

| 0.3 | Wind mixing effect coefficient | Determines the rate at which wind dilutes inhibitory substances. A value of 0.3 indicates a moderately effective mixing process. | |

| 0.5 | Wind resistance coefficient | Determines the rate at which wind suppresses fishing effort. A value of 0.5 reflects a sensitive fishery where operations are significantly curtailed by increasing wind speed. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yue, Q.; Bi, T.; Chen, F. Dynamics of a Wind-Driven Lotka–Volterra Amensalism System with Non-Selective Harvesting: Theoretical Analysis and Ecological Implications. Eng 2025, 6, 367. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120367

Yue Q, Bi T, Chen F. Dynamics of a Wind-Driven Lotka–Volterra Amensalism System with Non-Selective Harvesting: Theoretical Analysis and Ecological Implications. Eng. 2025; 6(12):367. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120367

Chicago/Turabian StyleYue, Qin, Taimiao Bi, and Fengde Chen. 2025. "Dynamics of a Wind-Driven Lotka–Volterra Amensalism System with Non-Selective Harvesting: Theoretical Analysis and Ecological Implications" Eng 6, no. 12: 367. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120367

APA StyleYue, Q., Bi, T., & Chen, F. (2025). Dynamics of a Wind-Driven Lotka–Volterra Amensalism System with Non-Selective Harvesting: Theoretical Analysis and Ecological Implications. Eng, 6(12), 367. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120367